Abstract

Objectives. To measure trends in infertility treatment use between 2008 and 2017 in France using data from the national health insurance system.

Methods. Between 2008 and 2017, we observed a representative national sample of nearly 1% of all women aged 20 to 49 years who were affiliated with the main health insurance scheme in France (more than 100 000 women observed each year). We exhaustively recorded all health care reimbursed to these women.

Results. Among women aged 20 to 49 years, 1.25% were treated for infertility each year. Logistic regression analysis showed a significant interaction between age and year of treatment use (P < .001). Over the decade, infertility treatment use increased by 23.9% among women aged 34 years or older, whereas among women younger than 34 years there was a nonsignificant variation.

Conclusions. Women aged 34 years or older were increasingly treated for infertility between 2008 and 2017.

Public Health Implications. Treatment efficiency decreases strongly with a woman’s age, presenting a challenge for medical infertility care.

The burden of infertility has been increasing since the 1990s worldwide and has had considerable public health consequences, including psychological distress, social stigmatization, economic strain, and marital discord.1 In developed countries, the increase in infertility may be attributable to environmental exposure and social changes, including a major trend of delaying parenthood to an age interval marked by higher risk of infertility.2,3

In the United States, more than 1 in 10 women of reproductive age have ever used infertility services.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have emphasized the need for the public health community to produce a more complete picture of infertility treatment use.5 The lack of data is largely attributable to the exclusive focus of most research on the most complex infertility care (i.e., assisted reproductive techniques). Developing a surveillance system to guide authorities in elaborating plans for infertility prevention, detection, and management would be an important benchmark in measuring the global use of infertility treatments.5

In the United States, the use of infertility treatments is hindered by access barriers because of significant cost and lack of adequate health insurance among socially vulnerable people.4,6 The global use of infertility treatments reflects both demand and access barriers. In France, 98% of residents (French and other nationalities) are covered by the health insurance system, which reimburses 100% of all infertility treatments. The French coverage of infertility treatment thus offers the opportunity to explore the global use of infertility treatment in a population-based approach and in a context of barrier-free financial access, although it has been shown that insurance coverage does not mean barrier-free access.7

Our objective was to assess the use of all infertility treatments in France between 2008 and 2017 using data from the French national health insurance database.

METHODS

In 2007, the French health insurance agency implemented a national sample including one ninety-seventh of the population covered by the main scheme (detailed presentation elsewhere8). Our study population was restricted to women aged 20 to 49 years.

We identified the list of infertility drugs using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We identified procedures related to assisted reproductive technology through the French classification system for medical acts (Classification commune des actes médicaux; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). For each year between 2008 and 2017, we classified a woman as having been treated for infertility during the year if she was reimbursed for at least 1 infertility drug or procedure. We measured the use of infertility treatments as the number of women treated divided by the number of women aged 20 to 49 years.

We modeled the association between infertility treatment use and the woman’s age using logistic regression. To test for a possible interaction with calendar year, we dichotomized age (threshold at 34 years) and included an interaction term with year. We carried out analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Based on more than 100 000 women aged 20 to 49 years observed each year (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), 1.25% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.23, 1.27) of women were treated for infertility each year (detail by year in Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, and Table C).

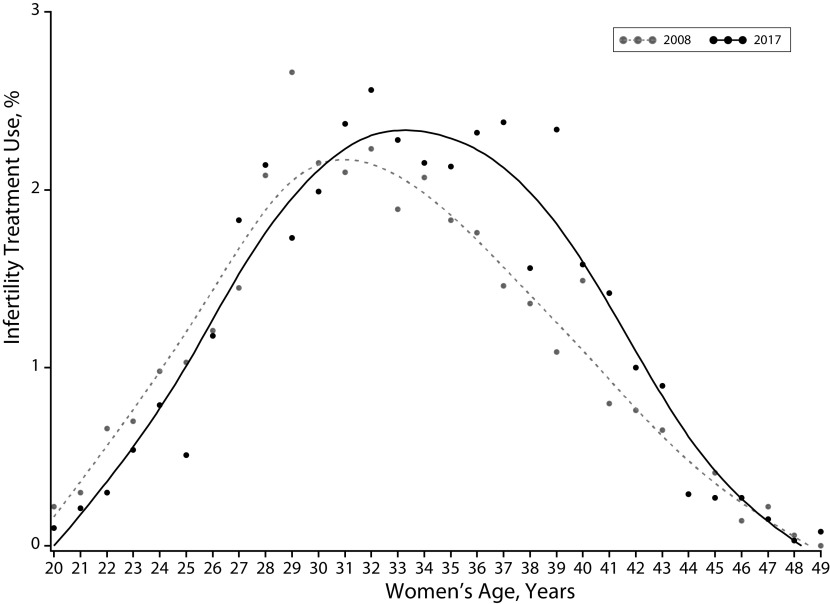

The mean age of treated women was 33.0 years in 2008 and 33.7 years in 2017 (P < .001). In 2008 and 2017, infertility treatment use by age followed a bell curve with a shift toward older ages in 2017 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Infertility Treatment Use According to Women’s Age: France, 2008–2017

Note. All infertility treatments are included (i.e., treatments with assisted reproductive technology [ART] and simple hormonal stimulation without ART). The figure shows women included in the one ninety-seventh sample of the French health insurance and affiliated with the main scheme. We used SAS INTERPOL = SM (for spline method) in PROC GPLOT (smoothing curve).

In logistic regression analysis, interaction between age and year of infertility treatment use was statistically significant (P < .001; Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Over the decade, infertility treatment use increased by 23.9% (95% CI = 14.66%, 33.74%; P = .001) among women aged 34 years or older, whereas, among women younger than 34 years, there was a nonsignificant variation of −5.00% (95% CI = −11.76%, 2.27%; P = .170).

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade in France, there has been a major increase in the use of infertility treatments among women aged 34 years and older but not among younger women.

In France, nearly all of the population (including non-French citizens) are fully covered for infertility treatments by the national health insurance scheme. This provides a unique opportunity to develop a strong and reliable population-based approach by considering all infertility treatments. However, potential limitations should be considered.

First, the study population included women covered by the main French health insurance scheme. This includes 76% of the total population and is considered a reliable source to study health in the French population.9 Other schemes have been progressively added to the national sample between 2011 and 2016. We carried out sensitivity analysis including all French schemes for the year 2017 (Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Results were reassuring, showing that the level of infertility treatment use and trend according to age was identical in our study population and in the population including all schemes.

Second, the French health insurance database does not include infertility treatment for French people who use cross-border reproductive care because of legal restrictions and an oocyte donation shortage in France.10 These restrictions are likely to affect a limited number of people: specifically, women aged 43 years and older, same-sex couples, single people, women seeking oocyte donation, and people seeking surrogacy.

Third, we measured the use of hormonal stimulation treatments through information on treatment purchasing. It cannot be ruled out that a few women may have purchased the treatment but not used it, for example, because they became pregnant naturally before starting treatment.

Finally, the French health insurance database includes almost no data on the sociodemographic profile of the patients. For example, it would be interesting to explore the role of nulliparous status. However, this variable is not available, and we could not create it based on previous reimbursement for pregnancy or childbirth, as the database was too recent and did not include earlier reimbursements.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first estimation of annual infertility treatment use in its entirety in a large population-based study. Estimates of global use of infertility treatments are mainly from the American National Survey of Family Growth, but they are lifetime estimates, and the size of the sample does not allow the exploration of annual estimates.4 A small Spanish study of 443 women aged 30 to 49 years estimated the prevalence of infertility diagnosis at 1.26%.11 This estimate is consistent with that observed in our study, but the outcome considered was different (infertility treatment use vs infertility diagnosis), and so was the age range of the population (20–49 years in our study vs 30–49 years in the Spanish study). One Canadian study explored change in treatment use over time according to age group and also observed increased use only among older women (30–44 years) and not among younger ones (20–29 years).12 However, this study considered only treatment by clomiphene citrate.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

The increase in infertility treatment use among women aged 34 years and older is consistent with the social and demographic delay in parenthood until older ages that has been described since 1970 in high-income countries.2 As the success rate of infertility treatments declines with women’s age, health policymakers and clinicians should be aware of this time trend, as it could have an important impact on infertility medical care. By developing surveillance of infertility treatment use by age, the public health community could better guide national and international strategies to prevent and manage infertility, which emerges as a growing and major health issue among middle-aged people.1,5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR StimHo project (grant ANR-17-CE36-0011-01).

We thank Nina Crowte for language assistance.

The StimHo Group includes the following: Elise de La Rochebrochard (coordinator, Institut national d’études démographiques [Ined]–Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale [Inserm]–Université Paris-Saclay [UVSQ]), Elodie Baril (Ined), Khaoula Ben Messaoud (Ined–Inserm–UVSQ), Pierre-Louis Bithorel, Bastien Bourrion (Inserm–UVSQ), Jean Bouyer (Inserm), Arnaud Bringé (Ined), Emmanuelle Cadot (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement), Annie Carré (Ined), Pierre Chauvin (Inserm), Mathilde François (Inserm–UVSQ), Elisabeth Morand (Ined), Nathalie Pelletier-Fleury (Inserm), Silvia Pontone (Robert Debré Hospital, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris [AP-HP]), Virginie Rozée (Ined), Jean-Paul Teglas (Inserm), Pénélope Troude (Saint-Louis–Lariboisière-Widal Hospital, AP-HP).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institut national d’etudes démographiques ethics committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sun H, Gong T-T, Jiang Y-T, Zhang S, Zhao Y-H, Wu Q-J. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: results from a Global Burden of Disease Study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(23):10952–10991. doi: 10.18632/aging.102497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.É Beaujouan, Reimondos A, Gray E, Evans A, Sobotka T. Declining realisation of reproductive intentions with age. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(10):1906–1914. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, Agarwal A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: taking control of your fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982–2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2014;(73):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macaluso M, Wright-Schnapp TJ, Chandra A et al. A public health focus on infertility prevention, detection, and management. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):16.e1–16.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers GM, Hoang V, Illingworth P. Socioeconomic disparities in access to ART treatment and the differential impact of a policy that increased consumer costs. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(11):3111–3117. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieke AC, Zhang Y, Kissin DM, Barfield WD, Boulet SL. Disparities in assisted reproductive technology utilization by race and ethnicity, United States, 2014: a commentary. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26(6):605–608. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, Ricordeau P, Merlière Y. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58(4):286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuppin P, Rudant J, Constantinou P et al. Value of a national administrative database to guide public decisions: from the système national d’information interrégimes de l’Assurance Maladie (SNIIRAM) to the système national des données de santé (SNDS) in France. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2017;65(suppl 4):S149–S167. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozée Gomez V, de La Rochebrochard E. Cross-border reproductive care among French patients: experiences in Greece, Spain and Belgium. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(11):3103–3110. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabrera-León A, Lopez-Villaverde V, Rueda M, Moya-Garrido MN. Calibrated prevalence of infertility in 30- to 49-year-old women according to different approaches: a cross-sectional population-based study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2677–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Temporal trends in clomiphene citrate use: a population-based study. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]