Abstract

Objectives. To describe characteristics of rural hospitals in the United States by whether they provide labor and delivery (obstetric) care for pregnant patients.

Methods. We used the 2017 American Hospital Association Annual Survey to identify rural hospitals and describe their characteristics based on the lack or provision of obstetric services.

Results. Among the 2019 rural hospitals in the United States, 51% (n = 1032) of rural hospitals did not provide obstetric care. These hospitals were more often located in rural noncore counties (counties with no town of more than 10 000 residents). Rural hospitals without obstetrics also had lower average daily censuses, were more likely to be government owned or for profit compared with nonprofit ownership, and were more likely to not have an emergency department compared with hospitals providing obstetric care (P for all comparisons < .001).

Conclusions. Rural US hospitals that do not provide obstetric care are located in more sparsely populated rural locations and are smaller than hospitals providing obstetric care.

Public Health Implications. Understanding the characteristics of rural hospitals by lack or provision of obstetric services is important to clinical and policy efforts to ensure safe maternity care for rural residents.

There has been a steady loss of rural hospital-based obstetric care across the United States. Approximately 9% of all rural counties lost hospital-based obstetric care between 2004 and 2014.1 These losses create access challenges for pregnant rural residents and are associated with increases in births in hospitals without obstetric care (planned services for pregnant patients during labor and childbirth).2,3

Closure of rural obstetric units is frequently precipitated by challenges related to low birth volume and sparsely populated locations (e.g., financing, staffing and scheduling, workforce recruitment and retention, and maintenance of clinical skills).4 Loss of hospital-based obstetric care is associated with an increased risk of births in hospital emergency departments and out-of-hospital births.2 There are also potential consequences for the infant, because the loss of hospital-based obstetric care has been associated with increased rates of preterm birth in rural counties nonadjacent to urban areas.2 In the United States, infant mortality is elevated in rural communities.5 Maternal morbidity and mortality are also elevated among rural residents, which may be exacerbated by limited access to care.6 Addressing these health disparities requires a detailed understanding of the rural obstetric care landscape. The purpose of this analysis was to describe the characteristics of rural hospitals based on whether they provide obstetric care and to inform clinical and policy discussions to improve rural maternal and infant health.

METHODS

Data for this analysis came from the 2017 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey, an annual survey mailed to administrators at all US hospitals, with a response rate of approximately 80%.7 We identified hospitals that provided obstetric care as those that indicated in the AHA survey that they had (1) an obstetric service line, (2) level 1 or higher maternity care, (3) at least 1 dedicated obstetric bed, and (4) 10 or more births per year. Any discrepancies were validated against the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Provider of Services file and hospital Web sites.

Hospital location was based on the Office of Management and Budget definition of metropolitan statistical areas.8 Rural counties include those classified as nonmetropolitan, both micropolitan counties (population center of 10 000–50 000) and noncore counties (population center of fewer than 10 000). Hospital location data were validated against the Area Health Resources Files. This analysis focused on rural hospitals only.

We examined financial structure, location, hospital size, and services. Financial structure included whether the hospital was a critical access hospital or a prospective payment system hospital, the type of ownership (government—nonfederal, government—federal, nongovernment—not-for-profit, or nongovernment—for-profit), and the percentage of inpatient days that were funded by Medicaid. Geographic location included rural county type (micropolitan or noncore) and adjacency to a metropolitan area. Hospital size and service measures included the annual number of emergency department visits, the proportion of hospitals without emergency departments, and the average daily census.

Among rural hospitals, we examined distributional differences between those that did and those that did not provide obstetric care, assessed by using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and mean and SD among continuous variables and tested by using the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and 2-sample t test for continuous variables. We conducted all analyses with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Accounting for 8 statistical tests, P values less than .006 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

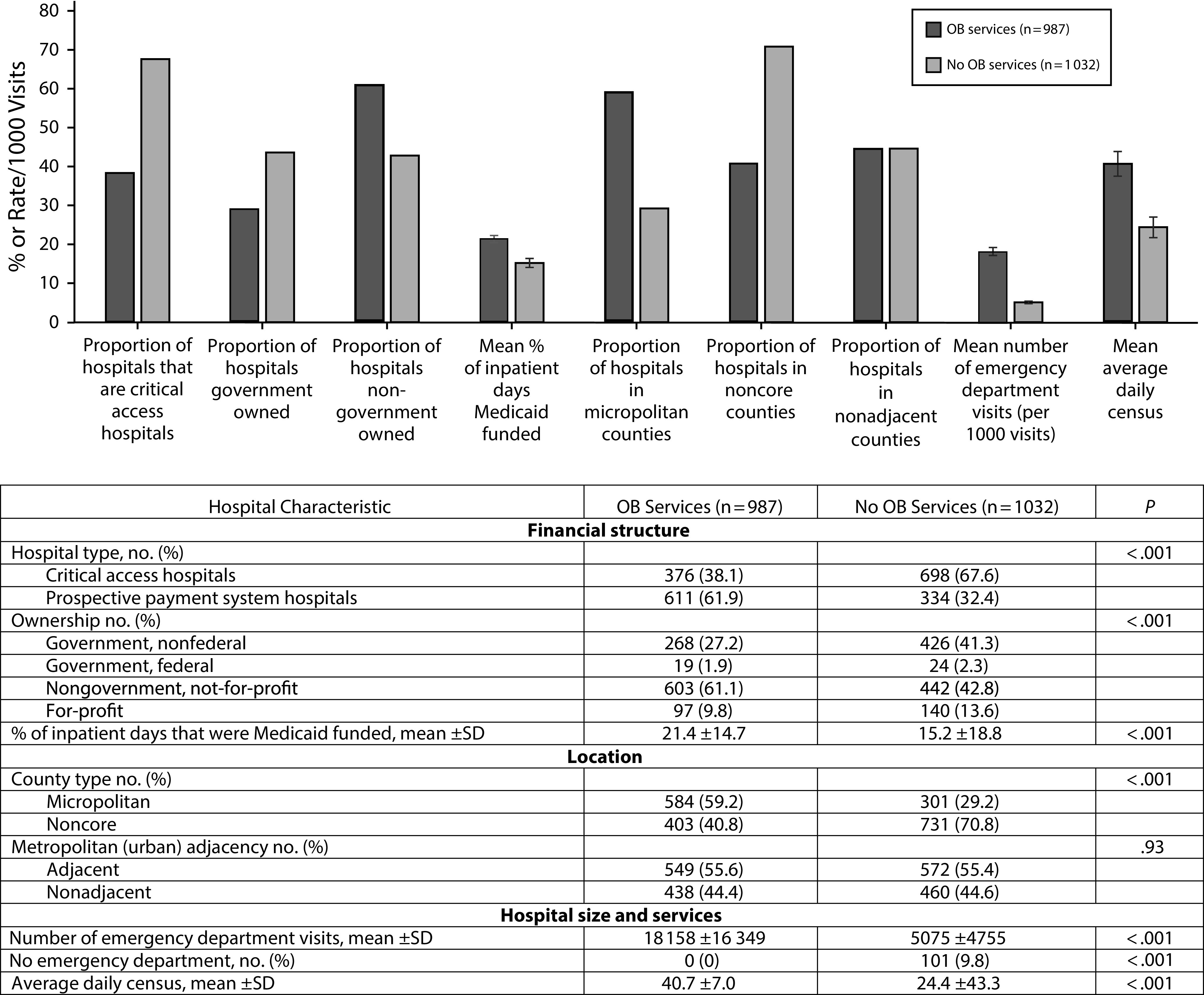

Among the 2019 rural hospitals in the 2017 AHA Annual Survey, 51.1% (n = 1032) did not provide obstetric care (Figure 1). Compared with rural hospitals that provided obstetric care, those that did not were more often critical access hospitals (67.6% vs 38.1%), government owned (43.6% vs 29.1%), or for profit (13.6% vs 9.8%). Hospitals without obstetric care had a lower proportion of inpatient days that were funded by Medicaid (15.2% vs 21.4%).

FIGURE 1—

Characteristics of Rural Hospitals by Obstetric Service Availability: United States, 2017

Note. OB = obstetric. The sample size was n = 2019. Error bars indicate SDs for mean values for continuous variables. P values are derived from the χ2 or Fisher exact test.

Rural hospitals that did not provide obstetric care were more often located in noncore counties than in micropolitan counties (70.8% noncore and 29.2% micropolitan vs 40.8% and 59.2%, respectively, among hospitals providing obstetric care).

Compared with rural hospitals with obstetric services, rural hospitals without obstetric care had one quarter the number of emergency department visits (no obstetrics, mean = 5075 visits; SD = 4755; obstetrics, mean = 18 158 visits; SD = 16 349) and an average daily census that was almost half the size of hospitals with obstetric care (no obstetrics, mean = 24.4 patients; SD = 43.3; obstetrics, mean = 40.7 patients; SD = 50.7). Furthermore, almost 10% of rural hospitals that did not provide obstetric care also did not have an emergency department, whereas all hospitals providing obstetric care had emergency departments. All differences were statistically significant at P < .001.

DISCUSSION

Rural US hospitals that do not provide obstetric care are located in less populous rural locations and have more limited size and clinical capacity. Specifically, we found that rural hospitals that did not provide obstetrics were more often government owned or for profit (vs nonprofit), were located in rural noncore counties (vs micropolitan), and had fewer emergency department visits and lower average daily censuses.

These findings provide critical new data on the current status of rural hospitals that do not provide obstetric care. Recognizing the potential public health consequences of lacking local obstetric care as well as loss of obstetrics,2,9 it is crucial to understand the resource constraints of rural hospitals without obstetric capacity to design programs and policies to ensure access to care, including emergency care, for pregnant rural residents.

Limitations

First, the AHA survey data do not contain quality metrics or patient outcomes and may be subject to respondent bias. However, the AHA survey is a widely used and trusted source that has been used previously to study rural obstetric care.1 Second, these data covered 1 year, not changes over time. Finally, these data do not reflect capacity of those hospitals without obstetric care to provide such care in emergencies, although we expect presence of an emergency department to serve as a surrogate for this in most cases. Future research should seek to understand the experience of rural patients and hospitals regarding emergency obstetric care.

Public Health Implications

From a clinical perspective, findings on characteristics of hospitals without obstetric services raise concerns about access to care when obstetric emergencies occur locally.10 Policies designed to improve maternal and infant health and to ensure access to necessary services should account for the particular constraints of rural health care settings. The smaller size and capacity of rural hospitals without obstetric care imply particular constraints on rural emergency obstetric care that may necessitate policy attention. For example, the critical access hospital program was established to provide essential access via hospitals with fewer beds, using a cost-based reimbursement strategy. Yet critical access hospitals are not required to provide obstetric care because of the high fixed costs of providing round-the-clock staff and clinicians capable of attending births.

Better data collection, resources for regional coordination, and training opportunities to ensure local capacity for emergency obstetrics are essential. Recently proposed federal legislation, the Rural Maternal and Obstetric Modernization of Services Act or Rural MOMS Act, would address many of these aspects of rural obstetric care access and quality.11 Additionally, state efforts, including maternal mortality review committees and perinatal quality collaboratives, may help to address some of these concerns, particularly when rural voices are included.12 Integrating an understanding of the characteristics of rural hospitals without obstetric care is essential to clinical and policy efforts to ensure safe maternity care for rural residents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for this study was provided by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration (cooperative agreement U1CRH03717-13-00).

Note. The information, conclusions, and opinions expressed are those of the authors, and no endorsement by Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration, or US Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This analysis was exempted by the University of Minnesota institutional review board.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004-14. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(9):1663–1671. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Henning-Smith C, Casey MM, Prasad S. Association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and birth outcomes in rural counties in the United States. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1239–1247. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krebs N. Rural Iowa’s dwindling options for maternal care. Iowa Public Radio. September 29, 2019. Available at: https://www.iowapublicradio.org/post/rural-iowa-s-dwindling-options-maternal-care. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- 4.Hung P, Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Moscovice IS. Why are obstetric units in rural hospitals closing their doors? Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ely DM, Driscoll AK, Matthews TJ. Infant mortality rates in rural and urban areas in the United States, 2014. NCHS data brief, no 285. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db285.htm. Accessed November 22, 2019. [PubMed]

- 6.Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Henning-Smith C, Admon LK. Rural-urban differences in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the US, 2007–15. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(12):2077–2085. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Hospital Association Center for Health Innovation. Data collection methods: the gold standard for hospital trend analysis. 2020. Available at: https://www.ahadata.com/data-collection-methods. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 8.Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician–Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, UNFPA, UNICEF, Mailman School of Public Health. Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care: A Handbook. 2009. Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241547734/en. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- 10.Robinson DW, Anana M, Edens MA et al. Training in emergency obstetrics: a needs assessment of US emergency medicine program directors. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(1):87–92. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.10.35273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. H.R.4243, Rural Maternal and Obstetric Modernization of Services (MOMS) Act, 116th Cong (2019-2020). Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/4243?s=1&r=23. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 12.Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Corbett A, Heppner S, Burges J, Henning-Smith C. Rural focus and representation in state maternal mortality review committees: review of policy and legislation. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(5):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]