Abstract

Background

Anastomotic leakage (AL) significantly impairs short-term outcomes. The impact on the long-term outcomes remains unclear. This study aimed to identify the risk factors for AL and the impact on long-term survival in patients with left-sided colorectal cancer.

Methods

Nine-hundred patients with left-sided colorectal carcinoma who underwent sigmoid or rectal resection were enrolled in the study. Risk factors for AL after sigmoid or rectal resection were identified, and long-term outcomes of patients with and without AL were compared.

Results

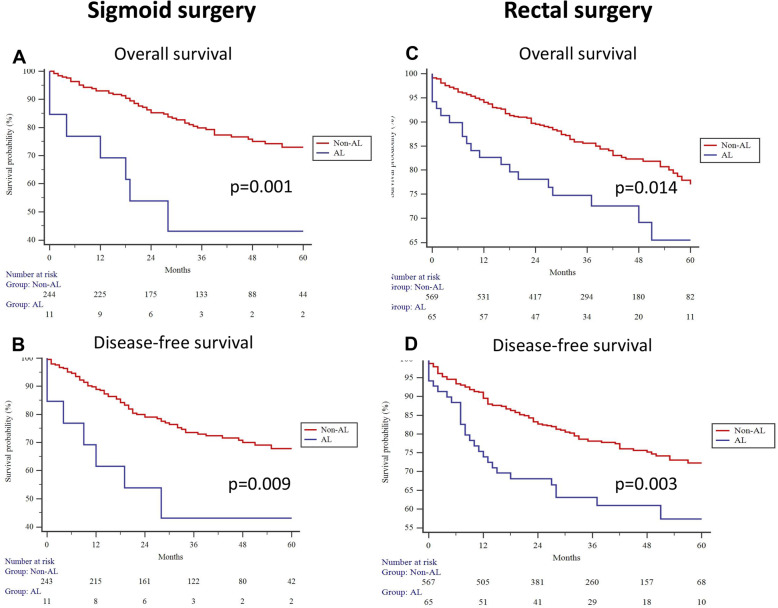

AL rates following sigmoid and rectal resection were 5.1% and 10.7%, respectively. Higher ASA score (III–IV; OR = 10.54, p = 0.007) was associated with AL in patients undergoing sigmoid surgery on multivariable analysis. Male sex (OR = 2.40, p = 0.004), CCI score > 5 (OR = 1.72, p = 0.025), and T3/T4 stage tumors (OR = 2.25, p = 0.017) were risk factors for AL after rectal resection on multivariable analysis. AL impaired disease-free and overall survival in patients undergoing sigmoid (p = 0.009 and p = 0.001) and rectal (p = 0.003 and p = 0.014) surgery.

Conclusion

ASA score of III–IV is an independent risk factor for AL after sigmoid surgery, and male sex, higher CCI score, and advanced T stage are risk factors for AL after rectal surgery. AL impairs the long-term survival in patients undergoing left-sided colorectal surgery.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Anastomotic leakage, Risk factors, Oncological outcomes, Overall survival, Disease-free survival

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most devastating complications following colorectal resection for left-sided colorectal cancer (CRC) [1]. It leads to increased morbidity, mortality, treatment costs, and prolonged hospitalization. The AL rate varies between 6 and 12% after rectal resection and between 2 and 4% after sigmoid resection [2]. Male sex, elderly age, obesity, severe comorbidities (higher American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score), prolonged surgery time, perioperative blood transfusions, low anastomosis, and neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy are proposed risk factors for AL [3, 4]. AL may occur in patients without any risk factors as well, and therefore, it remains a challenging issue in CRC surgery.

While AL has a negative impact on short-term surgical outcomes, the impact on long-term outcomes remains controversial. The study led by Karim et al. concluded that AL impairs overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) [5]. In contrast, Crippa et al. reported similar outcomes in patients with or without AL in terms of OS, DFS, and local recurrence rates [6]. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the impact of AL on the long-term outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for left-sided CRC and to identify the risk factors for AL after sigmoid and rectal resection.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Vilnius regional research ethics committee approval (no. 2019/3-116-608) was obtained before the study. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

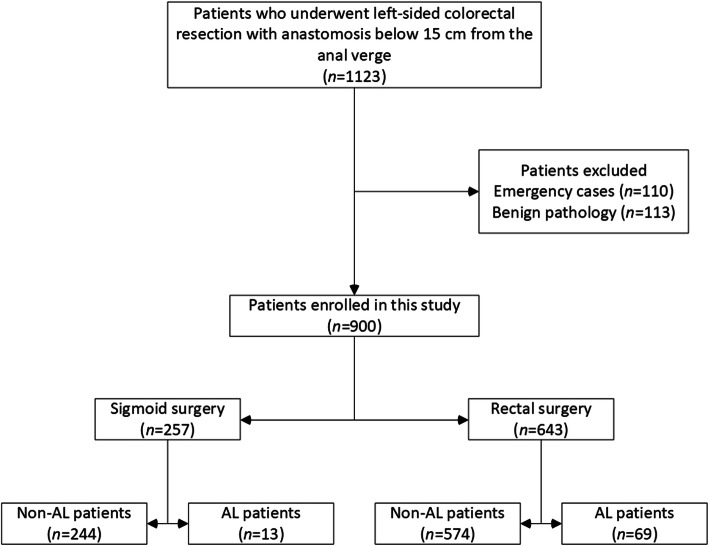

All patients who underwent left-sided colorectal resection with a primary anastomosis below 15 cm from anal verge between January 2014 and December 2018 at two major gastrointestinal cancer treatment centers in Lithuania—Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos and National Cancer Institute—were screened for eligibility. Patients who underwent emergency surgery or those with a benign pathology were excluded. Finally, all patients who underwent elective colorectal resection with primary anastomosis for left-sided CRC were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patients selection process

Data collection

All participants’ characteristics were obtained from the prospectively collected and maintained databases. They included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, comorbidities, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), history of neoadjuvant treatment, tumor localization, surgical approach (open surgery and minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopic surgery, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery, natural orifice specimen extraction surgery, and transanal total mesorectal excision surgery (taTME)), the level of the anastomosis, diverting ileostomy, simultaneous operation, high or low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), results of the intraoperative air-leak test, postoperative complications including AL, and the data of follow-up including progression of the disease. Tumor stage was coded according to the TNM system as described in the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was overall survival (OS) in patients with or without AL. The secondary outcomes included disease-free survival (DFS), 30-day mortality, and the risk factors for AL.

OS was defined as the time from surgery to death. Data on survival and date of death were collected from the National Lithuanian Cancer registry and the National Lithuanian death registry. Mortality registration rates, from both resources, were over 98%. DFS was defined as the time from surgery to disease progression including local or distant recurrence.

AL definition

AL was defined as a defect at the anastomotic area with a communication between the intra- and extra-luminal compartments. AL was confirmed by digital rectal examination, endoscopic evaluation, or radiologic tests with proven extravasation of rectal contrast or evidence of a peri-anastomotic fluid collection with pus or feculent aspirate [7].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed by statistical package SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Patients were grouped to those who developed AL (AL) and those who did not develop AL (non-AL). All data were checked for normality. Continuous variables were compared by a two-tailed t test, one-way ANOVA, or non-parametric tests where appropriate and expressed as means ± standard deviation or median with first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. Categorical data were expressed as proportions with percentages and compared by the chi-square test and Fisher exact test. To identify independent variables associated with anastomotic leakage, all potential risk factors were included in subsequent multivariable logistic regression analyses. Kaplan-Meier method was used for OS analysis, and survival curves were compared by the log-rank test. Multivariable survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model (hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals). A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant in all statistical analyses.

Results

Study participants

A total of 900 patients with a mean age of 65 ± 10 years were included in the study. For further analysis, patients were divided into sigmoid and rectal surgery sub-groups based on a tumor location. The AL rate after sigmoid and rectal surgery was 5.1% (13 of 257) and 10.7% (69 of 643), respectively. Baseline data of the patients are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the sigmoid and rectal surgery groups

| Sigmoid surgery (n = 257) | Rectal surgery (n = 643) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.4 ± 10.2 | 65.1 ± 10.9 | 0.172 | |

| BMI | < 30 | 152 (63.1%) | 472 (77.6%) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 30 | 89 (36.9%) | 136 (22.4%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 117 (45.5%) | 300 (46.7%) | 0.768 |

| Male | 140 (54.5%) | 343 (53.3%) | ||

| ASA | I–II | 160 (65.3%) | 430 (70.1%) | 0.167 |

| III–IV | 85 (34.7%) | 183 (29.9%) | ||

| CCI | ≤ 5 | 180 (70.0%) | 470 (73.1%) | 0.365 |

| > 5 | 77 (30.0%) | 173 (26.9%) | ||

| T stage | T0–T2 | 86 (33.5%) | 215 (33.4%) | 0.999 |

| T3–T4 | 171 (66.5%) | 428 (66.6%) | ||

| N stage | 0 | 149 (59.4%) | 392 (61.6%) | 0.822 |

| 1 | 72 (28.7%) | 172 (27.0%) | ||

| 2 | 30 (12.0%) | 72 (11.3%) | ||

| M stage | 0 | 218 (84.8%) | 592 (92.1%) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 39 (15.2%) | 51 (7.9%) | ||

| TNM stage | 0 | 5 (1.9%) | 7 (1.1%) | 0.006 |

| 1 | 66 (25.7%) | 160 (24.9%) | ||

| 2 | 71 (27.6%) | 198 (30.8%) | ||

| 3 | 75 (29.2%) | 227 (35.3%) | ||

| 4 | 40 (15.6%) | 52 (7.9%) | ||

| Approach of surgery | Open | 78 (30.4%) | 364 (56.6%) | 0.001 |

| MI | 179 (69.6%) | 279 (43.4%) | ||

| Postoperative complications | No | 208 (80.9%) | 413 (64.2%) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 49 (19.1%) | 230 (35.8%) | ||

| AL | No | 244 (94.9%) | 574 (89.3%) | 0.007 |

| Yes | 13 (5.1%) | 69 (10.7%) | ||

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score, CCI Charlson comorbidity index score, MI minimally invasive, AL anastomotic leakage

Risk factors for AL

Table 2 shows the univariate analysis of all potential risk factors for AL after sigmoid and rectal surgery. Higher ASA score (III–IV, p = 0.002) was associated with AL in patients undergoing sigmoid surgery, while male sex (p = 0.002), higher CCI score (> 5, p = 0.004), and advanced tumor stage (T3/T4, p = 0.031) was associated with AL in patients with rectal cancer.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for postoperative AL in sigmoid and rectal surgery

| Sigmoid surgery | Rectal surgery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-AL | AL | p value | Non-AL | AL | p value | ||

| (n = 244) | (n = 13) | (n = 574) | (n = 69) | ||||

| BMI | < 30 | 147 (96.7%) | 5 (3.3%) | 0.337 | 424 (89.8%) | 48 (10.2%) | 0.999 |

| ≥ 30 | 83 (93.3%) | 6 (6.7%) | 122 (89.7%) | 14 (10.3%) | |||

| Gender | Female | 111 (94.9%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.999 | 280 (93.3%) | 20 (6.7%) | 0.002 |

| Male | 133 (95.0%) | 7 (5.0%) | 294 (85.7%) | 49 (14.3%) | |||

| ASA | I–II | 158 (98.8%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.002 | 389 (90.5%) | 41 (9.5%) | 0.154 |

| III–IV | 76 (89.4%) | 9 (10.6%) | 158 (86.3%) | 25 (13.7%) | |||

| CCI | ≤ 5 | 172 (95.6%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.538 | 430 (91.5%) | 40 (8.5%) | 0.004 |

| > 5 | 72 (93.5%) | 5 (6.5%) | 144 (83.2%) | 29 (16.8%) | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | Yes | 13 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.999 | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.551 |

| No | 231 (94.7%) | 13 (5.3%) | 548 (89.4%) | 65 (10.6%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 28 (90.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | 0.197 | 54 (84.4%) | 10 (15.6%) | 0.200 |

| No | 216 (95.6%) | 10 (4.4%) | 520 (89.8%) | 59 (10.2%) | |||

| History of CVD | Yes | 8 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.999 | 17 (89.5%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.999 |

| No | 236 (94.8%) | 13 (5.2%) | 557 (89.3%) | 67 (10.7%) | |||

| Chronic renal failure | Yes | 4 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.999 | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.999 |

| No | 240 (94.9%) | 13 (5.1%) | 566 (89.3%) | 68 (10.7%) | |||

| Neoadjuvant treatment | Yes | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.378 | 161 (88.0%) | 22 (12.0%) | 0.484 |

| No | 236 (95.2%) | 12 (4.8%) | 413 (89.8%) | 47 (10.2%) | |||

| Approach of surgery | Open | 71 (91.0%) | 7 (9.0%) | 0.069 | 320 (87.9%) | 44 (12.1%) | 0.247 |

| MI | 173 (96.6%) | 6 (3.4%) | 254 (91.0%) | 25 (9.0%) | |||

| Anastomosis level from anal verge | ≤ 5 | 20 (95.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0.999 | 155 (89.1%) | 19 (10.9%) | 0.137 |

| 6–12 | 235 (86.4%) | 37 (13.6%) | |||||

| > 12 | 178 (93.7%) | 12 (6.3%) | 81 (94.2%) | 5 (5.8%) | |||

| Ileostomy | Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100%) | 0.051 | 330 (88.5%) | 43 (11.5%) | 0.519 |

| No | 244 (95.3%) | 12 (4.7%) | 244 (90.4%) | 26 (9.6%) | |||

| T stage | T0–T2 | 84 (97.7%) | 2 (2.3%) | 0.230 | 200 (93.0%) | 15 (7%) | 0.031 |

| T3–T4 | 160 (93.6%) | 11 (6.4%) | 374 (87.4%) | 54 (12.6%) | |||

| N stage | 0 | 143 (96%) | 6 (4.0%) | 0.253 | 357 (91.1%) | 35 (8.9%) | 0.130 |

| 1 | 70 (97.2%) | 2 (2.8%) | 149 (86.6%) | 23 (13.4%) | |||

| 2 | 27 (90.0%) | 3 (10%) | 61 (84.7%) | 11 (15.3%) | |||

| M stage | 0 | 209 (95.9%) | 9 (4.1%) | 0.117 | 531 (89.7 %) | 61 (10.3 %) | 0.238 |

| 1 | 35 (89.7%) | 4 (10.3%) | 43 (84.3 %) | 8 (15.7 %) | |||

| TNM stage | 0 | 5 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.221 | 6 (85.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0.568 |

| 1 | 64 (97.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 147 (91.9%) | 13 (8.1%) | |||

| 2 | 68 (95.8%) | 3 (4.2%) | 178 (89.9%) | 20 (10.1%) | |||

| 3 | 72 (96.0%) | 3 (4%) | 200 (88.1%) | 27 (11.9%) | |||

| 4 | 35 (87.5%) | 5 (12.5%) | 43 (84.3%) | 8 (15.7%) | |||

| Ligation of IMA | High | 189 (95.9%) | 8 (4.1%) | 0.165 | 442 (88.4%) | 58 (11.6%) | 0.265 |

| Low | 50 (90.9%) | 5 (9.1%) | 117 (92.1%) | 10 (7.9%) | |||

| Simultaneous operation | Yes | 20 (90.9%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0.308 | 53 (85.5%) | 9 (14.5%) | 0.286 |

| No | 224 (95.3%) | 11 (4.7%) | 521 (89.7%) | 60 (10.3%) | |||

| Air-water test | Yes | 121 (96.8%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.255 | 454 (88.7%) | 58 (11.3%) | 0.429 |

| No | 119 (93.0%) | 9 (7.0%) | 116 (91.3%) | 11 (8.7%) | |||

BMI body mass index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score, CCI Charlson comorbidity index score, CVD cardiovascular disease, MI minimally invasive, IMA inferior mesenteric artery, AL anastomotic leakage

Further, the multivariable analysis confirmed a higher ASA score (III–IV; OR = 10.539; p = 0.007) as an independent risk factor for AL after sigmoid surgery (Table 3). The same analysis confirmed male sex (OR = 2.403, p = 0.004), higher CCI score (> 5, OR = 1.720, p = 0.025), and advanced tumor stage (T3/4, OR = 2.250; p = 0.017) were among risk factors for AL after rectal surgery (Table 4).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for postoperative AL in sigmoid surgery

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.962 | 0.878–1.054 | 0.632 | |

| Gender | Male | 0.834 | 0.179–3.882 | 0.784 |

| BMI | > 30 | 1.519 | 0.283–8.153 | 0.119 |

| ASA | III–IV | 10.539 | 1.292–85.976 | 0.007 |

| CCI | > 5 | 0.348 | 0.029–4.199 | 0.928 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 2.150 | 0.285–16.233 | 0.095 |

| Surgery type | Palliative | 1.726 | 0.052–57.273 | 0.601 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | Yes | 9.657 | 0.269–346.401 | 0.307 |

| Anastomosis type | Stapled | 0.901 | 0.092–8.821 | 0.316 |

| Ligation of IMA | High | 0.670 | 0.093–4.848 | 0.081 |

| Air-water test | No | 1.084 | 0.060–19.593 | 0.187 |

| Simultaneous operation | Yes | 1.318 | 0.088–19.748 | 0.904 |

| T stage | T3–T4 | 0.887 | 0.122–6.470 | 0.408 |

| Approach of surgery | Open | 0.438 | 0.070–2.731 | 0.079 |

BMI body mass index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score, CCI Charlson comorbidity index score, IMA inferior mesenteric artery, AL anastomotic leakage

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for postoperative AL in rectal surgery

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 2.403 | 1.204–4.797 | 0.004 |

| Age | 0.994 | 0.962–1.026 | 0.307 | |

| BMI | > 30 | 0.858 | 0.389–1.894 | 0.495 |

| ASA | III–IV | 1.346 | 0.635–2.854 | 0.156 |

| CCI | > 5 | 1.720 | 0.759–3.898 | 0.025 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 1.297 | 0.478–3.522 | 0.155 |

| Ischemic heart disease | Yes | 0.933 | 0.250–3.487 | 0.303 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Yes | 1.090 | 0.185–6.432 | 0.644 |

| Surgery type | Palliative | 0.606 | 0.059–6.273 | 0.980 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | Yes | 1.430 | 0.645–3.170 | 0.260 |

| Anastomosis type | Stapled | 1.310 | 0.125–13.727 | 0.809 |

| Ligation of IMA | High | 2.345 | 0.939–5.856 | 0.167 |

| Air-water test | No | 1.339 | 0.529–3.392 | 0.350 |

| Ileostomy | No | 0.884 | 0.405–1.930 | 0.749 |

| Simultaneous operation | Yes | 1.188 | 0.436–3.237 | 0.450 |

| T stage | T3–4 | 2.250 | 1.052–4.815 | 0.017 |

| Approach of surgery | Open | 0.633 | 0.316–1.269 | 0.186 |

| Anastomosis level from anal verge | < 5 | 3.286 | 0.933–11.569 | 0.064 |

| Anastomosis level from anal verge | 5–12 | 2.629 | 0.636–10.868 | 0.182 |

BMI body mass index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score, CCI Charlson comorbidity index score, IMA inferior mesenteric artery, AL anastomotic leakage

AL and 30- and 90-day mortality

The 30-day mortality rate was higher in patients with AL in the sigmoid (15.4% vs 0%, p = 0.002) and rectal (5.8% vs 1%, p = 0.016) surgery sub-groups. Similarly, 90-day mortality rate remained higher in leaking patients (sigmoid 15.4% vs 1.6%, p = 0.032; rectal 8.7% vs 2.1%, p = 0.008).

AL and long-term outcomes

The median time of follow-up was 38 (Q1 22; Q3 53) months. The AL after sigmoid surgery impaired OS and DFS (Fig. 2a, b). Similarly, the AL impaired OS and DFS (Fig. 2c, d) after rectal surgery.

Fig. 2.

Overall and disease-free survival in sigmoid and rectal surgery

Further, AL was adjusted for the stage of the disease, gender, age, and comorbidities (CCI score) by COX regression analysis in the study cohort. After, the AL remained a significant factor for impaired OS (HR (95% CI) 1.53 (1.01–2.32), p = 0.041) and DFS (HR (95% CI) 1.51 (1.05–2.19), p = 0.026) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cox regression (multivariable) analysis for overall and disease-free survival in the study cohort

| Overall survival | Disease-free survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Anastomotic leakage | No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 1.53 (1.01–2.32) | 0.041 | 1.51 (1.05–2.19) | 0.026 | |

| Stage of disease | I | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| II | 1.26 (0.72–2.20) | 0.403 | 1.52 (0.93–2.48) | 0.090 | |

| III | 2.28 (1.38–3.78) | 0.001 | 2.94 (1.88–4.59) | 0.001 | |

| IV | 5.87 (3.26–10.56) | 0.001 | 6.04 (3.51–10.38) | 0.001 | |

| Gender | Male | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Female | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) | 0.832 | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 0.714 | |

| Age (years) | ≤ 55 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| 56–70 | 1.15 (0.71–1.85) | 0.566 | 1.02 (0.70–1.49) | 0.889 | |

| ≥ 71 | 1.90 (1.16–3.11) | 0.010 | 1.15 (0.76-1.73) | 0.498 | |

| Comorbidities by CCI | 0–5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| ≥ 6 | 2.48 (1.64–3.74) | 0.001 | 2.14 (1.48–3.10) | 0.001 | |

CCI Charlson comorbidity index score

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that AL impairs long-term outcomes of the patients undergoing surgery for sigmoid and rectal cancer. Severe comorbidities, male sex, and advanced tumor stage are the risk factors for AL.

Several recent studies investigated the risk factors for AL because the identification of high-risk patients and avoidance of anastomosis in these patients could improve treatment outcomes [8–12]. Previously, studies demonstrated male gender as a risk factor for AL after rectal surgery, and our results were consistent with these findings [3, 8, 9, 13, 14]. Male gender is thought to increase the AL rate because of more technically demanding surgery in the narrow and deeper pelvis of men [13]. There is a possibility that hormonal functions may impact anastomotic healing as well [15, 16]. The advanced stage of tumor also makes surgery more technically challenging, and it was confirmed as another risk factor for AL by our study. Interestingly, we did not find a higher AL rate in patients receiving low anastomosis. These findings are conflicting with some previous reports indicating a higher risk for low anastomoses [3, 17]. Although, in our results, there was a strong tendency for higher AL rate in low anastomoses (≤ 5 cm (10.9%) vs 6–12 cm (13.6%) vs > 12 cm (5.8 %), p = 0.137), and it might be that our study was underpowered to detect significant differences because of the relatively small sample size.

Lower anastomoses may be secured by diverting ileostomy. However, the evidence on the impact of ileostomy on preventing the leak or reducing the symptoms is conflicting. Two meta-analyses concluded that stoma reduces the rate of AL following low anterior resection [12, 18]. In contrast, our study did not confirm that ileostomy prevents AL. This finding is consistent with some previous studies [19, 20]. A temporary ileostomy may not prevent the AL but rather diminish its symptoms and consequences. Further, the true rate of AL in patients receiving ileostomy may be underestimated because usually asymptomatic patients do not undergo testing for anastomosis integrity at the early postoperative period [21, 22]. Similarly, in our study, asymptomatic patients underwent anastomosis integrity testing just before the ileostomy closure; thus, some cases of AL in patients who receive ileostomy might have been underestimated as well. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the role of ileostomy in the prevention of the AL.

The existing data on AL impact on the long-term outcomes are conflicting as well. A recent study from the Mayo Clinic revealed similar OS, DFS, and local recurrence rates between patients with or without AL [6]. Propensity score-matched analysis by Sueda et al. also demonstrated a similar OS rate in AL and non-AL patients, except the higher rate of local recurrence in case of leakage [23]. In contrast, the previous meta-analysis by Bashir et al. concluded that patients with AL have a lower 5-year OS of 58% compared with 73% in non-leaking patients [24]. Moreover, the negative impact of AL on OS was indicated by Yang et al. and a large Scandinavian cohort study by Stormark et al. [25, 26]. Our study confirmed the impaired OS and DFS in patients suffering from AL, and there is a rationale for such findings. First, AL may lead to an increased rate of local recurrence because of cancer cell implantation and progression at the inflamed leaking anastomotic site [27, 28]. Despite AL occurs after surgical tumor removal, several viable tumor cells remain intraluminally, proximally, and distally to cancer sites [29]. These cells were identified after the rectal wash-out or were washed-out from histologically tumor-free stapled doughnuts [30, 31]. The pre-clinical model confirms these intraluminal cancer cells can implant at the anastomotic site and initiate tumor growth in experimental animals [32]. Additionally, the leakage results in a local inflammation, which may further contribute to the increased risk of tumor cell implantation and proliferation at the anastomotic site [33]. Moreover, the AL is associated with an increased systemic inflammatory response as shown by increased levels of CRP, and such condition may be related to the development and progression of the malignancy [34, 35]. AL is also associated with the delay or omission of the adjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, AL may have a negative impact on long-term outcomes, especially in patients with the advanced stage of the disease, where adjuvant chemotherapy is necessary [36–39].

The present study has some limitations, including the retrospective design of the study. However, a considerable sample size, multicenter approach, and significant national registry-based long-term follow-ups increase the power of the study to demonstrate that AL is associated with impaired long-term outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for left-sided CRC. Future research is needed to find strategies to reduce or prevent the rate of AL in such patients [40].

Conclusion

ASA score of III–IV is an independent risk factor for AL after sigmoid surgery, and male sex, higher CCI score, and advanced tumor stage are among risk factors for AL after rectal surgery. AL impairs the long-term survival in patients undergoing left-sided colorectal surgery.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

Study conception design: Kryzauskas M., Bausys A., Poskus E., Dulskas A., Strupas K., Poskus T., Bausys R. Data acquisition: Degutyte A.E., Abeciunas V., Poskus T., Bausys R. Data analysis and interpretation: Kryzauskas M., Bausys A., Poskus T. Drafting the article: Kryzauskas M., Bausys A., Degutyte A.E., Abeciunas V., Poskus T., Bausys R. Critical revision for intellectual content: Poskus E., Dulskas A., Strupas K., Poskus T., Bausys R. Final approval of the manuscript: Kryzauskas M., Bausys A., Degutyte A.E., Abeciunas V., Poskus E., Dulskas A., Strupas K., Poskus T., Bausys R. Agree to be accountable for all aspects of work to ensure that questions regarding accuracy & integrity investigated and resolved: Kryzauskas M., Bausys A., Degutyte A.E., Abeciunas V., Poskus E., Dulskas A., Strupas K., Poskus T. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Vilnius regional research ethics committee approval (no. 2019/3-116-608) was obtained before the study. Individual patient consent is not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12957-020-01968-8.

References

- 1.Park JS, Huh JW, Park YA, et al. Risk factors of anastomotic leakage and long-term survival after colorectal surgery. Medicine. 2016;95(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Leichtle SW, Mouawad NJ, Welch KB, Lampman RM, Cleary RK. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(5):569–575. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182423c0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu H, Liu Y. Bi D-s. Clinical risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(12):3608–3617. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu M-H, Huang R-K, Zhao R-S, Yang K-L, Wang H. Does neoadjuvant therapy increase the incidence of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for mid and low rectal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Disease: The Official Journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2017;19(1):16–26. doi: 10.1111/codi.13424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karim A, Cubas V, Zaman S, Khan S, Patel H, Waterland P. Anastomotic leak and cancer-specific outcomes after curative rectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Crippa J, Duchalais E, Machairas N, Merchea A, Kelley SR, Larson DW. Long-term oncological outcomes following anastomotic leak in rectal cancer surgery. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, et al. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147(3):339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85(3):355–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon RT, Chu KW, Ho JW, Chan CW, Law WL, Wong J. Prospective evaluation of selective defunctioning stoma for low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. World J Surg. 1999;23(5):463–467. doi: 10.1007/PL00012331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law WI, Chu KW, Ho JW, Chan CW. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. Am J Surg. 2000;179(2):92–96. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäkelä JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after left-sided colorectal resection with rectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(5):653–660. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6627-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S-W, Ma C-C, Yang Y. Role of protective stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2014;20(47):18031–18037. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.18031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Andersson M, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Colorectal Disease: The Official Journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2004;6(6):462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P. Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Color Dis. 2008;23(3):265–270. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ba ZF, Yokoyama Y, Toth B, Rue LW, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Gender differences in small intestinal endothelial function: inhibitory role of androgens. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286(3):G452–G457. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00357.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sah BK, Chen M-M, Peng Y-B, et al. Does testosterone prevent early postoperative complications after gastrointestinal surgery? World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2009;15(44):5604–5609. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi DH, Hwang JK, Ko YT, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic rectal resection. Journal of the Korean Society of Coloproctology. 2010;26(4):265–273. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2010.26.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montedori A, Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Sciannameo F, Abraha I. Covering ileo- or colostomy in anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;5:CD006878. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006878.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong NY, Eu KW. A defunctioning ileostomy does not prevent clinical anastomotic leak after a low anterior resection: a prospective, comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(11):2076–2079. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salamone G, Licari L, Agrusa A, et al. Usefulness of ileostomy defunctioning stoma after anterior resection of rectum on prevention of anastomotic leakage A retrospective analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bausys A, Kuliavas J, Dulskas A, et al. Early versus standard closure of temporary ileostomy in patients with rectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(2):294–299. doi: 10.1002/jso.25488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KH, Kim HO, Kim JS, Kim JY. Prospective study on the safety and feasibility of early ileostomy closure 2 weeks after lower anterior resection for rectal cancer. Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research. 2019;96(1):41–46. doi: 10.4174/astr.2019.96.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sueda T, Tei M, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Prognostic impact of postoperative intra-abdominal infections after elective colorectal cancer resection on survival and local recurrence: a propensity score-matched analysis. Int J Color Dis. 2020;35(3):413–422. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bashir Mohamed K, Hansen CH, Krarup P-M, Fransgård T, Madsen MT, Gögenur I. The impact of anastomotic leakage on recurrence and long-term survival in patients with colonic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology: The Journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2020;46(3):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Chen Q, Jindou L, Cheng Y. The influence of anastomotic leakage for rectal cancer oncologic outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Stormark K, Krarup P-M, Sjövall A, et al. Anastomotic leak after surgery for colon cancer and effect on long-term survival. Colorectal Disease. 2020;. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Skipper D, Jeffrey MJ, Cooper AJ, Alexander P, Taylor I. Enhanced growth of tumour cells in healing colonic anastomoses and laparotomy wounds. Int J Color Dis. 1989;4(3):172–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01649697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGregor JR, Galloway DJ, George WD. Intra-luminal tumour cells and peri-anastomotic tumour growth in experimental colonic surgery. European Journal of Surgical Oncology: The Journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 1992;18(4):368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umpleby HC, Fermor B, Symes MO, Williamson RC. Viability of exfoliated colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Surg. 1984;71(9):659–663. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenner DC, de Boer WB, Clarke G, Levitt MD. Rectal washout eliminates exfoliated malignant cells. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(11):1432–1434. doi: 10.1007/BF02237063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gertsch P, Baer HU, Kraft R, Maddern GJ, Altermatt HJ. Malignant cells are collected on circular staplers. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35(3):238–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02051014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kluger Y, Galili Y, Yossiphov J, Shnaper A, Goldman G, Rabau M. Model of implantation of tumor cells simulating recurrence in colonic anastomosis in mice. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(12):1506–1510. doi: 10.1007/BF02237297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terzić J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2101–2114.e2105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poskus E, Karnusevicius I, Andreikaite G, Mikalauskas S, Poskus T, Strupas K. C-reactive protein is a predictor of complications after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery: five-year experience. Wideochirurgia I Inne Techniki Maloinwazyjne = Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 2015;10(3):418–422. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.54077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu H, Ouyang W, Huang C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Molecular cancer research: MCR. 2006;4(4):221–233. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim IY, Kim BR, Kim YW. The impact of anastomotic leakage on oncologic outcomes and the receipt and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after colorectal cancer surgery. International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 2015;22:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung SH, Yu CS, Choi PW, et al. Risk factors and oncologic impact of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(6):902–908. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kube R, Mroczkowski P, Granowski D, et al. Anastomotic leakage after colon cancer surgery: a predictor of significant morbidity and hospital mortality, and diminished tumour-free survival. European Journal of Surgical Oncology: The Journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2010;36(2):120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eberhardt JM, Kiran RP, Lavery IC. The impact of anastomotic leak and intra-abdominal abscess on cancer-related outcomes after resection for colorectal cancer: a case control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(3):380–386. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ad488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kryzauskas M, Poskus E, Dulskas A, et al. The problem of colorectal anastomosis safety. Medicine. 2020;99(2):e18560. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.