Abstract

We show the distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) genetic clades over time and between countries and outline potential genomic surveillance objectives. We applied three genomic nomenclature systems to all sequence data from the World Health Organization European Region available until 10 July 2020. We highlight the importance of real-time sequencing and data dissemination in a pandemic situation, compare the nomenclatures and lay a foundation for future European genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, NGS, WGS, sequencing, nomenclature, Europe

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, whole genome sequencing (WGS) has been used extensively by laboratories all over the world to characterise the virus. To be able to implement continuous monitoring of genetic changes through WGS as part of surveillance at the European level, surveillance objectives and virus nomenclatures need to be defined. In this report, we applied the available nomenclatures to the European subset of the GISAID dataset to describe broad geographical and temporal trends in the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 genetic clades during the first half of 2020 and we discuss potential genomic surveillance objectives at the European level.

Genome data availability during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is the first pandemic where WGS capacity has been widely available to the public health sector from the beginning. Since the first genomes were published in January 2020 [1-4], the number of available sequences has rapidly increased to more than 63,000 complete genome sequences available in GISAID as at 10 July [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) European Region has been an active contributor, with around 39,000 complete genome sequences from 35 countries published in GISAID, with a median time of 40 days from sample collection to publication according to the GISAID collection and submission dates. Of those sequences, 8% were published within 2 weeks of collection and 0.6% of sequences were published within 1 week of collection. Supplementary Figure S1 summarises the number of genomes sampled and submitted per month. A detailed account of the turnaround time for each country is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. This demonstrates that with enough resources, it is possible to set up and perform real-time WGS and global analysis of a newly emerged virus.

Clade nomenclatures for SARS-CoV-2

One major component of sequence-based surveillance of any pathogen is applying meaningful nomenclatures to the sequence data, based on the genetic relatedness of the sequences. This streamlines communication between different actors in the molecular epidemiology field and enables simplified tabulation of the genomic data for integration with classical epidemiological analysis.

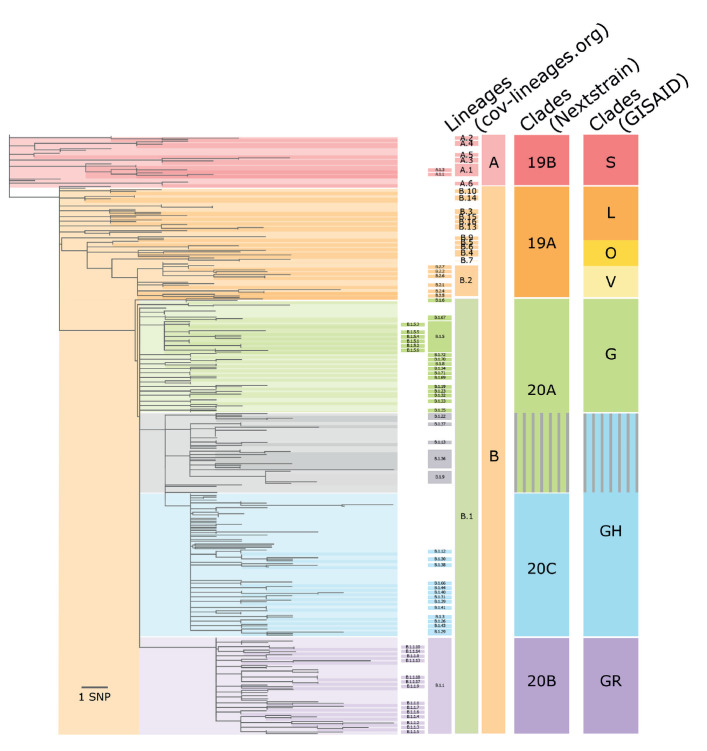

Several nomenclatures have been introduced for SARS-CoV-2 (strains in GISAID use the name hCoV-19), including by Nextstrain [6], GISAID [7] and Rambaut et al. (cov-lineages.org) [8-10]. While Nextstrain and GISAID clade nomenclatures aim at providing a broad-brush categorisation of globally circulating diversity, the lineages (cov-lineages.org) are meant to correspond to outbreaks. The relation between the three nomenclatures is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of the GISAID, Nextstrain and cov-lineages.org nomenclatures for SARS-CoV-2 sequences of world-wide origin, February–July 2020

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism.

A schematic tree is shown, representing the major topological features of the SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny. The tree is shaded to correspond to the major lineages and all Nextstrain and GISAID clades. Between Nextstrain clades 20A and 20C and GISAID clades G and GH, there are differences in the position where clades are divided (shown as grey in the main tree and lineage columns, and grey stripes in the Nextstrain and GISAID column). Here, the grey is shown as stripes in the Nextstrain and GISAID clade columns to reflect how they are categorised by each methodology. Association between the lineages and clades is approximate. The sequence data available from GISAID were curated using the Pangolin data preparation pipeline [8]. In brief, we masked out singleton substitutions identified in the pipeline and selected a set of representatives per lineage or clade. We aligned the sequences using MAFFT v7.470 [14] and estimated a maximum likelihood phylogeny using IQ-Tree v1.6.12 with 10,000 ultrafast bootstraps [15,16]. Sequence EPI_ISL_406801 (Wuhan/WH04/2020), a basal A lineage sequence, was used as an outgroup for the tree. We visualised the tree using baltic with custom python scripts and manual edits [17].

Agreement on a single nomenclature is a major global undertaking that cannot be decided at the national or European level. Major success factors of nomenclature systems include adoption of the nomenclature by major actors in the field, fitness for purpose to the surveillance objectives, compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and availability on software platforms. Currently, the available SARS-CoV-2 nomenclatures do not attempt to reflect any antigenic or other phenotypic properties of the virus.

Distribution of clades over time

Sequence data were downloaded from GISAID on 10 July 2020.

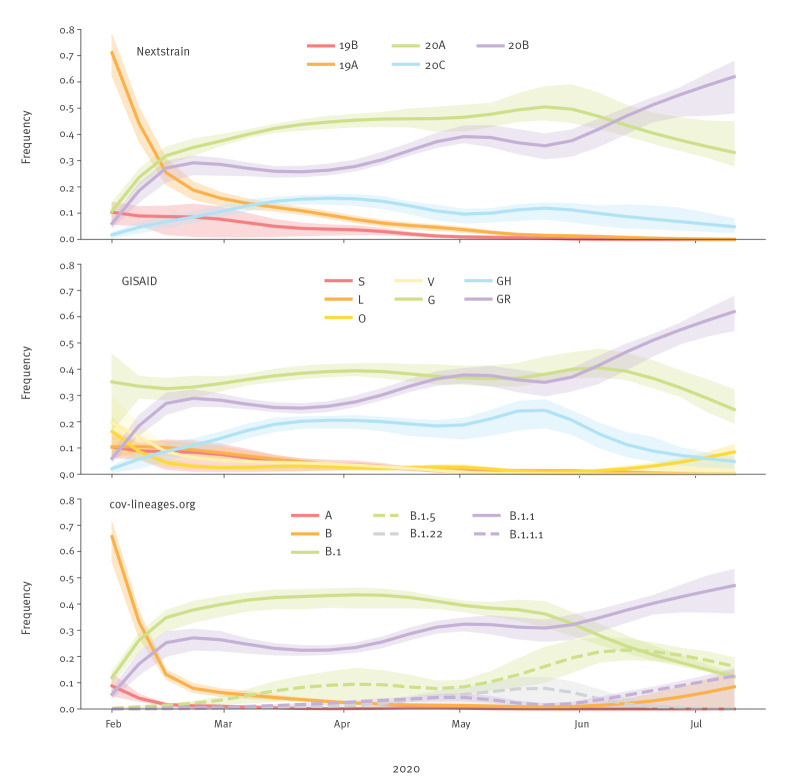

The subsampled distribution of clades and lineages over time in the WHO European Region is shown in Figure 2. There was an initial period in January 2020 when the 19A/L/V/O clades (Nextstrain/GISAID nomenclatures) were more prevalent in total than the 20A/G clades, However, this could partially be an effect of small numbers of sequenced viral genomes in Europe early in the pandemic as well as the widespread sampling strategy focusing on cases with travel history to East Asia. The 20A/G clades are characterised by the spike protein D614G mutation that has been suggested to increase transmissibility but not pathogenicity [11]. After this initial stage, the 20B/GR clade increased rapidly, stabilised around 30% between March and May 2020 and increased further to become the most frequent clade in June 2020. The trajectory for the 20C/GH clades differs slightly depending on the nomenclature applied. The Nextstrain 20C clade peaked at ca 20% of the sequences in early April 2020 and has since then slowly declined and almost disappeared, while the GISAID GH clade peaked at ca 30% in May 2020 and has rapidly declined since then. The changing trends at the end of the data series could partially be explained by different delays from sampling to publication for different countries with different clade distributions.

Figure 2.

Frequency trajectories of SARS-CoV-2 clades and lineages by collection date, WHO European Region, February–July 2020 (n = 37,187, subsampled to 3,324)

From top to bottom: Nextstrain, GISAID and cov-lineages.org. Shaded areas: interquartile ranges obtained by bootstrap resampling the dataset by country. Fewer sequences from fewer countries are available in recent weeks, resulting in widening confidence intervals. Frequency trajectories were generated from a sample representative across sampling time and space using the augur filter routine and selecting 15 random sequences for each month and administrative division [18]. When fewer than 15 sequences were available, all data were included. Frequencies were calculated using Gaussian smoothing with a standard deviation of 10 days. Script is available from https://github.com/neherlab/ncov-ecdc/.

When applying the cov-lineages.org nomenclature, the main A and B lineages were prevalent in January and then diversified rapidly into sublineages which had stable frequencies from late February 2020 to end of April 2020; thereafter, an increase in the frequency of B.1.1 (corresponds to clade 20B/GR) and B.1.5 (part of clade 20A/G) lineages can be observed.

Clade distribution in the WHO European Region countries

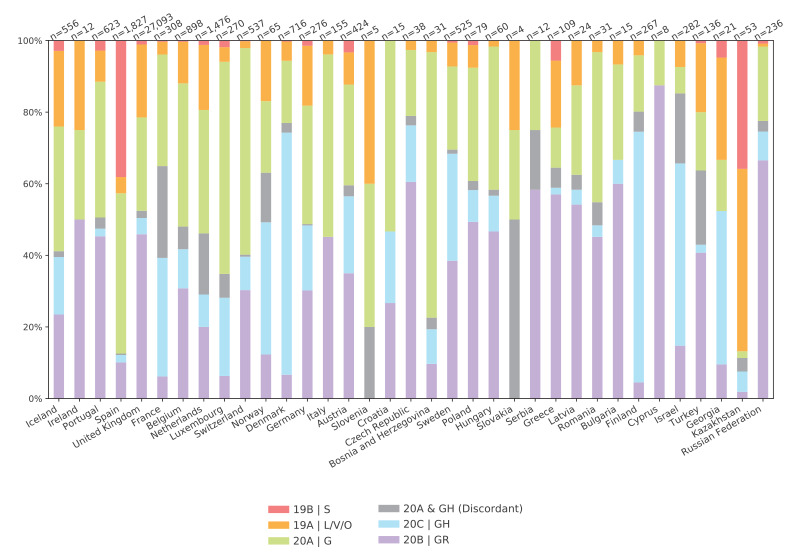

The geographical distribution of Nextstrain and GISAID clades shows that in general, clade 19B/S has been very rare, except in Spain and Kazakhstan, and frequencies of the other clades were varied for most countries in the WHO European Region (Figure 3). For countries with few sequences, the clade distribution may be unreliable, and there may be a bias towards the clades that dominated at different stages of the pandemic depending on varying sampling strategies over time and the timeliness of the submission of sequences.

Figure 3.

Distribution of GISAID and Nextstrain clades of SARS-CoV-2 across countries in the WHO European Region, based on all high-quality genomes in GISAID, February– July 2020 (n = 37,187)

The numbers at the top of each bar indicate the number of available genomes. The grey areas represent sequences called differently by the GISAID and Nextstrain methodologies, and correspond to the grey-shaded partition of the tree in Figure 1. Supplementary Figure S3 shows the same data using the cov.lineages.org nomenclature. The proportion of clades found in each country was calculated using all available full-length, high-quality (> 27,000 bases, < 3,000 undetermined bases) sequences available on GISAID. Clade membership for each sequence was determined by given GISAID annotation or via the Nextstrain clades script, and proportions were calculated for all sequences from a given country. Script is available from https://github.com/neherlab/ncov-ecdc/

Among the countries with more than 100 sequences available, Spain stands out with a high proportion of clades 19B/S and 20A/G and very little of the other clades, Denmark, Finland and Israel with a high proportion of 20C/GH, Greece, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom with no or very little 20C/GH and the Russian Federation and Switzerland with very little 19A/L/V/O. The distribution may depend on founder effects and sampling bias, but also on when and for how long travel restrictions and national response measures were implemented. Early travel restrictions would probably have reduced the early incidence and therefore the 19A/L/V/O clades that were most prevalent before the 20A/G-clades became dominant, while travel restrictions and lockdowns implemented later could have preserved the clade distribution as it was at the time of the implementation.

Discussion about SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance in the WHO European Region

Through discussions in a call open to all laboratories in the WHO European region submitting SARS-CoV-2 sequences to GISAID, we identified the following key surveillance objectives for the use of SARS-CoV-2 sequence data at the European level.

Current (January 2020 and onward):

Investigating transmission dynamics and introductions of novel genetic variants;

Investigating the relationship between clades/lineages and epidemiological data such as transmissibility and disease severity or risk groups to guide public health action;

Understanding the impact of response measures on the virus population;

Assessing the impact of mutations on the performance of molecular diagnostic methods;

Assessing the impact of mutations on the performance of serological methods.

Future (when antiviral drugs and vaccines become available):

Assessing the impact of mutations on the performance of antiviral drugs;

Assessing the impact of mutations and modelling the antigenic properties of the virus to assess the risk of vaccine escape.

All of these objectives benefit from a representative sample of the virus population. The first three also depend to a large degree on data completeness, which is a limitation in the currently available dataset where the number of sequences per country ranges from four to 28,000. Rapid sequencing is crucial for real-time outbreak analysis, for instance to show that the flare-up in June 2020 in Beijing [12] was caused by virus variants similar to those circulating in Europe or to demonstrate separate introductions to mink farms in the Netherlands [13].

The experience of sequencing SARS-CoV-2 in Europe to date demonstrates the potential for rapidly sharing genomic data to support national and international public health response. A genomic surveillance guidance that takes the variable resources in the region into account is necessary to fully realise this potential. GISAID made a global, curated sharing system for SARS-CoV-2 sequences available early in the pandemic, and the benefits of available tools for early sharing of sequences have been demonstrated during this pandemic through rapid implementation of diagnostic tests and monitoring of the viral characteristics over time. Implementing real-time genomic surveillance at the European level could further elucidate differences in circulating strains between countries and enhance the understanding of how response measures, and later vaccines and antiviral drugs, affect the proportion of genetic variants.

Conclusions

Overall, the GISAID and Nextstrain nomenclatures provide similar pictures of the situation and may provide useful systems for genomic situation reporting globally. The cov-lineages.org nomenclature provides information at a finer scale and has the potential to provide early warning of expanding lineages that may represent regional outbreaks or later become dominant because of some selective advantage such as vaccine escape or increased transmissibility.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the authors, originating and submitting laboratories of the sequences from GISAID’s EpiCoV Database used in the phylogenetic analysis.

We gratefully acknowledge all the staff working with sample collection, sample preparation, sequencing, data analysis and data sharing in all laboratories in the WHO European Region for making this work possible.

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Supplementary Data

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contribution: Writing the manuscript: Erik Alm, Eeva K Broberg, Thomas Connor, Emma Hodcroft, Sebastian Maurer-Stroh, Richard Neher, Áine O’Toole, Andrey B Komissarov. Analysing the GISAID dataset: Erik Alm, Emma Hodcroft, Andrey B. Komissarov, Richard Neher, Áine O’Toole. Providing conceptual ideas for the inception of the manuscript: Erik Alm, Eeva K Broberg, Thomas Connor, Emma Hodcroft, Sebastian Maurer-Stroh, Angeliki Melidou, Richard Neher, Áine O’Toole, Dmitriy Pereyaslov, Etienne Simon-Loriere, Vítor Borges, Krzysztof Pyrc, Ilker Karacan, Gabriel Gonzalez, Andrey B Komissarov. Generating and analysing the sequence data: The WHO European Region sequencing laboratories, GISAID EpiCov group. Critically reviewing the manuscript for intellectual content: All authors.

References

- 1. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen Y-M, Wang W, Song Z-G, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265-9. 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ren L-L, Wang Y-M, Wu Z-Q, Xiang Z-C, Guo L, Xu T, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133(9):1015-24. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shu Y, McCauley J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data - from vision to reality. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(13):30494. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nextstrain: Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus - Global subsampling. [Accessed: 10 Jul 2020]. Available from: https://nextstrain.org/ncov

- 7.Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). Clade and lineage nomenclature aids in genomic epidemiology studies of active hCoV-19 viruses. Munich: GISAID; 4 Jul 2020. Available from: https://www.gisaid.org/references/statements-clarifications/clade-and-lineage-nomenclature-aids-in-genomic-epidemiology-of-active-hcov-19-viruses/

- 8.Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak LINeages (pangolin). San Francisco: GitHub. [Accessed: 10 Jul 2020]. Available from: https://github.com/cov-lineages/pangolin

- 9. Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O’Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, Ruis C, et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020. Ahead of print. 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O’Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone J, Ruis C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 lineages. [Accessed: 10 Jul 2020]. Available from: https://cov-lineages.org/

- 11. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;S0092-8674(20)30820-5. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO). A cluster of COVID-19 in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Geneva: WHO; 13 Jun 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/13-06-2020-a-cluster-of-covid-19-in-beijing-people-s-republic-of-china

- 13. Oreshkova N, Molenaar RJ, Vreman S, Harders F, Oude Munnink BB, Hakze-van der Honing RW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(23):2001005. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.23.2001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772-80. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268-74. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(2):518-22. 10.1093/molbev/msx281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.baltic: the Backronymed Adaptable Lightweight Tree Import Code. GitHub. [Accessed: 10 Jul 2020]. Available from: https://github.com/evogytis/baltic

- 18. Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(23):4121-3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.