Abstract

Objective:

Patient satisfaction is emerging as a new health-care metric. We hypothesized that an emergency department (ED) informational pamphlet would significantly improve patient understanding of ED operations and ultimately improve patient satisfaction.

Methods:

We performed a prospective study of patients presenting to a single tertiary care center ED from April to July 2017. All patients were given a pamphlet on alternating weeks with regular care on opposite weeks and were surveyed upon ED discharge. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction with ED care. Secondary outcomes included patient understanding of various wait times (test results, consultants), discharge process, who was on the care team and what to expect during the ED visit.

Results:

Four hundred ninety-four patients were included in this study and 266 (54%) were in the control group. Of 228 (46%) patients who were given the pamphlet, 116 (51%) were unaware they received it. Of the remaining 112 (49%) patients who remembered receiving the pamphlet, 43 (38%) stated they read it. Among those reading the pamphlet, only two statements were significant: knowing what to expect during the ED visit (88% vs 71%; P = 0.012) and waiting time for test results (95% vs 75%; P = 0.003) when compared to those who did not receive or read the pamphlet.

Conclusion:

An ED informational pamphlet, when utilized by patients, does improve patient understanding of some aspects of the ED visit but does not appear to be the best tool to convey all information. Ultimately, sustained improvement in patient satisfaction is a complex and dynamic issue necessitating a multifactorial approach and other methods should be explored.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, patient expectations, communication, emergency medicine

Introduction

Although clinical outcomes are the mainstay of measuring patient care, patient satisfaction has emerged as an important outcome for health-care providers (1,2). Satisfaction is a result of patient perception and expectation: a patient will experience higher satisfaction if their expectations are low and perception of their experience is high (3). Multiple studies have suggested that an increase in patient satisfaction translates to increased patient adherence to treatment, trust in physicians, improved hospital efficiency and clinical outcomes, and potentially improved utilization of care (4,5). As patient satisfaction continues to play a more significant role in delivery of care, reimbursements have begun to be tied to this metric (1,2,4). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed an emergency department (ED) specific satisfaction survey similar to the hospital surveys already implemented nationally (6).

Prior research examining patient preferences with regard to ED care suggests patients desire increased staff communication and information regarding their ED visit (7 -9). For example, one-third to one-half of patients do not understand the purpose of triage or why later arriving patients may be evaluated sooner (9). Patients consistently report a desire for information concerning delays, how the ED works, and information pertaining to their visit such as visitors and food (7,9). Paper handouts such as business cards and informational sheets have been studied previously. These studies showed a trend toward improved patient satisfaction but had methodological limitations such as pre/post design, small sample size, narrow window of patient enrollment, and short study duration (10 -12).

We evaluated the effect of an informational paper pamphlet explaining ED operations as a cost-effective tool to improve patient experience. We hypothesized that an ED pamphlet explaining the basic elements of an ED visit such as the role of triage, waiting time for test results, visitor policy, and frequently asked questions would significantly improve patient understanding of ED operations and ultimately improve patient satisfaction.

Methods

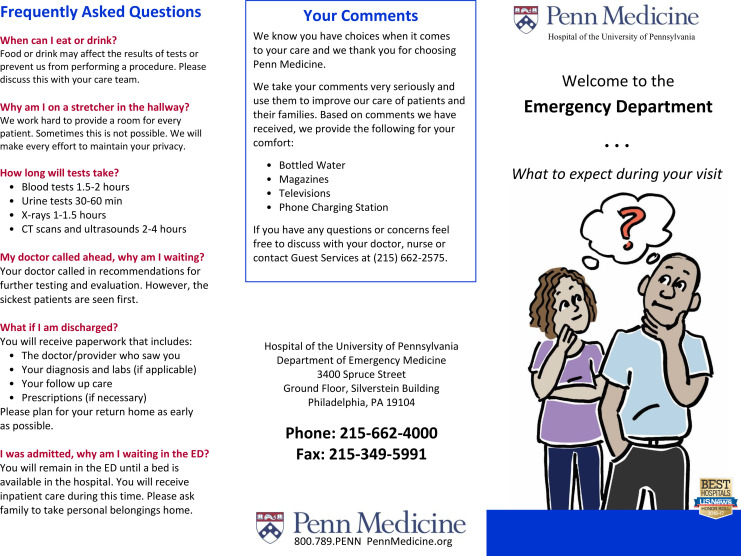

Using a prospective experimental design, we conducted an intervention trial using a convenience sample of adults presenting to an urban, academic ED over a 16-week study period between April and July 2017. Only patients who were English speaking and discharged home from the ED were included. Within this group, patients who had history of dementia or otherwise unable to communicate directly with ED staff were excluded. Our ED census is about 65 000 patients per year with an approximate 26% admission rate. The study intervention was an informational pamphlet developed and pilot tested with patient and staff input. The pamphlet contained a variety of information regarding an ED visit such as triage process, visitor policy, defining the care team, and frequently asked questions. The pamphlet is available in Appendix B. The pamphlet was distributed at the time of ED registration on alternating 2-week blocks with usual care on opposite weeks. The intervention processes and outcomes were studied by administering an 8-question, previously used survey at ED discharge by trained research assistants between the hours of 7 am and midnight (13). The survey utilized a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree) on questions about patient understanding different components of the pamphlet and is available in Appendix A. The pamphlet and survey were approved by hospital data scientists to ensure CMS compliance and reviewed by the hospital’s Patient and Family Advisory Council to avoid gender and racial bias and to ensure an appropriate fourth grade reading level. Additional data including patient demographics, Emergency Severity Index (ESI) level, ED location, and ED throughput time stamps were collected. ED location consisted of 2 subcategories including Fast Track and the Main ED. In general, Fast Track cares for ESI level 4 and 5 patients while the Main ED cares for ESI level 1 to 3 patients. We included this distinction given Fast Track has higher throughput rates and may itself affect patient satisfaction. The primary outcome was patient overall satisfaction with ED care as measured by the survey. Secondary outcomes included patient knowledge of what to expect during the ED visit, time to receive test results, who was on the care team, wait time to see a specialist consultant, and understanding the discharge process during the ED visit.

To determine differences in demographics based on whether or not the patient received and read the pamphlet compared to not looking at the pamphlet or remember receiving it versus the control group, chi-squared (χ2 tests) for categorical variables, and a 1-way analysis of variance for patient age, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for ED length of stay and triage to room time were performed. Similarly, to assess patient satisfaction based on whether or not the patient received and read the pamphlet, responses were dichotomized and exact tests were performed. Additionally, logistic regression adjusting for demographics was performed. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). This project was reviewed and determined to qualify as quality improvement by the Hospital’s institutional review board.

Results

Of 494 patients surveyed at time of discharge, the mean age was 42.1 years (range: 18-91), 305 (62%) were female, 325 (66%) were black/African American, and 235 (48%) were assigned an ESI of 3. Of 228 (46%) patients who were given the pamphlet, 116 (51%) were unaware they received it. Of the remaining 112 (49%) patients who remembered receiving the pamphlet, 43 (38%) stated they read it, and of these patients 41 (95%) found the pamphlet helpful. Patients who reported looking at the pamphlet compared to patients who did not read or receive it were similar with regard to gender, race/ethnicity, age, ESI, ED location, and time from triage to room (Table 1). Patients who read the pamphlet had a statistically significant longer waiting time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Characteristic | Looked at Pamphlet | Did Not Look at Pamphlet | Control | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender (Female) | 26 | 60.5 | 121 | 65.4 | 158 | 59.4 | 0.42 |

| Race ethnicity | 0.27 | ||||||

| Black AA | 27 | 62.8 | 121 | 65.4 | 177 | 66.5 | |

| White/Caucasian | 13 | 30.2 | 49 | 26.5 | 55 | 20.7 | |

| Other | 3 | 7 | 15 | 8.1 | 34 | 12.8 | |

| Age in yearsa | 43.6 (17.8) | 42.7 (17.4) | 41.4 (16.6) | 0.59 | |||

| Emergency Severity Index | 0.09 | ||||||

| 2 | 7 | 16.3 | 55 | 29.7 | 62 | 23.3 | |

| 3 | 26 | 60.5 | 88 | 47.6 | 121 | 45.5 | |

| 4-5 | 10 | 23.3 | 42 | 22.7 | 83 | 31.2 | |

| Location | 0.46 | ||||||

| Fast track | 9 | 20.9 | 36 | 19.5 | 65 | 24.4 | |

| Main ED | 34 | 79 | 149 | 80.5 | 201 | 75.6 | |

| Triage to room (minutes)b | 47 (18-126) | 37 (16-82) | 29 (13-81) | 0.22 | |||

| Total length of stay (hours)b | 6.4 (3.6-9.5) | 5.2 (3.3-6.8) | 4.5 (3.0-7.0) | 0.04 | |||

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

a Mean (standard deviation): tested for significance using 1-way analysis of variance.

b Median (interquartile range): tested for significance using Kruskal-Wallis test.

When examining the 8 survey statements by the 3 groups, there was no difference between the control and patients who did not look at or know they received the pamphlet (P value range: 0.27 to >0.99). Therefore, these 2 groups were combined as those not interacting with the pamphlet behave as if they were in the control group. Patients who reported looking at the pamphlet were more likely to agree or strongly agree with each of the 8 survey statements compared to patients who did not receive or look at the pamphlet (difference in proportions range from 1% to 20%; Figure 1). However, of the secondary outcomes, only 2 statements were statistically significant: knowing what to expect during the ED visit (88% vs 71%; P = 0.012) and waiting time for test results (95% vs 75%; P = 0.003). Logistic regression analyses using the 3 groups and adjusting for patient and ED characteristics did not alter these results.

Figure 1.

Difference in percent of patients who agree or strongly agree with the different emergency department visit survey questions between those who read the pamphlet and those who were in the control group, did not remember receiving the pamphlet or did not read the pamphlet.

Discussion

The delivery of care based on value and outcomes is under constant pursuit. More recently, there has been a shift toward patient satisfaction as a metric to which hospital reimbursements will be tied (14). Prior research suggests patients who feel informed regarding their ED visit have increased satisfaction, despite prolonged wait times (10,11,15 -17). In 2010, Press Ganey released a report of more than 1.5 million patient responses across nearly 1900 hospitals in the United States to varying survey questions. Patients who reported receiving information about delays in their care had higher satisfaction scores independent of their time waiting to be seen (17). We chose to implement an ED pamphlet as a cost-effective medium to keep patients informed and set appropriate expectations for ED operations. Furthermore, the pamphlet, if successful had potential to be scaled up to other EDs in the health system and customized to meet specific needs.

Our results demonstrate that informing patients about the ED process significantly improves certain visit expectations such as knowing what to expect during the ED visit and time to obtain test results. This might be expected as patients come to the ED for testing and spend most of the visit waiting for results. Although not significant for the remaining questions, the results trend in the positive direction (Figure 1) suggesting that the pamphlet may have a positive impact on patient satisfaction; however, there was no statistical difference in the primary outcome of improving overall patient satisfaction.

A study in 2004 by Sun and colleagues found no improvement in patient satisfaction following receipt of a single page information form (18). Although we have a similar study design, patient characteristics, and sample size to this prior study, our results are opposite. Although this may indicate the benefit of our multipage information tool (with the drawback of decreased patient engagement), it likely reflects a key difference in methodology. Contrary to Sun et al (2004), we obtained data on pamphlet dissemination and patient use which revealed significant differences in those who actually utilized the pamphlet as opposed to an effectiveness study. Our results demonstrated 38% of patients who remembered receiving the pamphlet (19% of the pamphlet group as a whole) reported reading the pamphlet, and in contrast to Sun et al, our analyses evaluated this subgroup of patients rather than evaluating all patients who received the pamphlet regardless of their interaction with the pamphlet.

Limitations

Some of the limitations of this study relate to low patient engagement. First of all, more than half of patients given the pamphlet did not remember receiving the pamphlet and more still did not read this pamphlet. Interestingly, patients who reported reading the pamphlet had a statistically significant waiting room time compared to others possibly indicating longer waits prompt patients to read material given to them. Despite this, we did find significant differences in certain questions asked. Improved scripting or dissemination by different staff members may improve pamphlet acceptance. Another option would be to create an ED informational video that plays on the television mixed with regular programing. This has been tried in other research studies with positive results (15,16). We elected to use a pamphlet given cost, informational technology system limitations, and to demonstrate proof of concept. Second of all, this study had opportunity for sampling bias as patients were surveyed between 7 am and midnight during times of research associate availability. Not only would this have affected both patient cohorts, but the off hours represent the lowest volume times for patient presentation and likely had minimal impact on the results. Third of all, this was not a randomized control trial thus raising the potential for confounders. However, given the alternating 2-week blocks, any systemic changes in departmental process would have had an effect on both the control and intervention groups. Finally and anecdotally, ED staff welcomed the pamphlet project and inquired about it at the completion of the study. This suggests the triage staff may have noticed a change in the waiting room during intervention weeks that we may not have been able to measure using the survey.

Future directions should focus on ways to increase patient engagement with information provided. With regard to the pamphlet, having someone, such as a triage nurse, hand out the pamphlet with defined scripting may increase patient awareness of the pamphlet and subsequently increase their engagement. The use of a waiting room video has been tried previously with positive results but takes increased front-end planning, funding, and information technology involvement to integrate into preexisting systems (15,16). With the increase in mobile devices and hospitals utilizing patient portals, there exist opportunities to bring information directly to patients possibly in the form of a mobile application or direct text messaging.

Conclusion

In summary, an ED informational paper pamphlet, when utilized by patients, does improve patient understanding of some aspects of the ED visit but does not appear to be the best tool to convey all information as there appeared to be lack of patient engagement. Despite this, it is a simple, straightforward cost-effective intervention that may augment other methods to keep patients informed during their ED visit. Ultimately, meaningful sustained improvement in patient satisfaction is a complex and dynamic issue necessitating a multifactorial approach and other methods should be explored.

Author Biographies

Rohit B Sangal is a chief resident at the University of Pennsylvania Emergency Medicine Residency Program.

Clinton J Orloski is an emergency medicine attending physician at Northwest Hospital in Seattle Washington. He is a former Chief Resident at the University of Pennsylvania Emergency Medicine Residency Program.

Frances S Shofer is the director of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. She is also serves as core faculty for the Occupational Medicine Residency, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Residency and the Masters of Public Health Program at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

Angela M Mills is the J. E. Beaumont professor and Chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons and Chief of Emergency Medicine Services for NewYork-Presbyterian|Columbia. She was previously the Vice Chair of Clinical Operations and Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Only Answer Questions 1, 2, and 3 if this is a “Study” Week.

| Yes | No | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did you receive our welcome pamphlet today? | □ | □ | |||||

| 2. If so, did you look at it? | □ | □ | |||||

| 3. How helpful was this information? | |||||||

| □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Not at All | Somewhat Helpful | Helpful | Extremely Helpful | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Not Applicable | |||

| 4. I understood why I waited in the waiting room before being brought back to the treatment area. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| 5. I understood who the members of my care team were. | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| 6. I understood how long it would take for my test results (blood, X-rays). | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| 7. I understood how long it would take to be seen by a specialist or consultant (eg: neurologist, cardiologist, or general surgeon) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||

| 8. I felt anxious during my emergency room visit today. | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| 9. I knew what to expect during my visit in the emergency room | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| 10. I understood the process of being discharged | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| 11. I was satisfied with today’s visit. | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| 12. Please use this space to provide any additional comments regarding the way in which doctors and nurses communicated with you and your family. (continue on the back if needed) | |||||||

Thank you for your participation in this survey!

Appendix B Emergency Department Patient Pamphlet

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Browne K, Roseman D, Shaller D, Edgman-Levitan S. Analysis & commentary. Measuring patient experience as a strategy for improving primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:921–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maister DH. The Psychology of Waiting Lines. Boston: Harvard Business School; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Hays RD, Lehrman WG, Rybowski L, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71:522–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Services CfMaM. Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey. Baltimore, MD: Services CfMaM; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kington M, Short AE. What do consumers want to know in the emergency department? Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:406–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwartz LR, Overton DT. Emergency department complaints: a one-year analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seibert T, Veazey K, Leccese P, Druck J. What do patients want? Survey of patient desires for education in an urban university hospital. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:764–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kologlu M, Agalar F, Cakmakci M. Emergency department information: does it effect patients’ perception and satisfaction about the care given in an emergency department? Eur J Emerg Med. 1999;6:245–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krishel S, Baraff LJ. Effect of emergency department information on patient satisfaction. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:568–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schiermeyer RP, Tayal V, Butzin CA. Physician business cards enhance patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:125–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orloski C, Tabakin E, Shofer F, Myers J, Mills A. Grab a SEAT: nudging providers to sit improves the patient experience in the emergency department. J Patient Exp. 2018; Retrieved March 2018 from: 10.1177/2374373518778862. Accessed July 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sonis JD, Aaronson EL, Lee RY, Philpotts LL, White BA. Emergency department patient experience: a systematic review of the literature. J Patient Exp. 2018;5:101–06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corbett SW, White PD, Wittlake WA. Benefits of an informational videotape for emergency department patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papa L, Seaberg DC, Rees E, Ferguson K, Stair R, Goldfeder B, et al. Does a waiting room video about what to expect during an emergency department visit improve patient satisfaction? CJEM. 2008;10:347–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emergency Department. Patient Perspectives on American Health Care. Pulse Report. South Bend: Press Ganey; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun BC, Brinkley M, Morrissey J, Rice P, Stair T. A patient education intervention does not improve satisfaction with emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]