ABSTRACT

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that was initially described in Wuhan China in December 2019. In the USA (US), the person to be diagnosed with the novel Coronavirus infection (COVID) was on 19 January 2020. On 18 March 2020, a 31-year-old morbidly obese African American woman presented with severe dyspnea with associated hypoxemia, fever and bilateral interstitial pulmonary ground glass infiltrates consistent with viral pneumonitis. Nasopharyngeal PCR testing was positive for SARS-CoV-2. Despite initiation of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin along with supplemental oxygen therapy, rapid disease progression consistent with cytokine release syndrome ensued, leading to initiation of mechanical ventilatory support. Anti-Interleukin (IL)-6 receptor monoclonal antibody (tocilizumab) was administered. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) leads to refractory hypoxemia and demise. Severe morbid obesity as well as race may be unidentified risk factors for the development of severe Illness in patients with COVID-19.

KEYWORDS: COVID19, morbid obesity, race, risk factors, mortality

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the 2019 novel Coronavirus, was first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) by CDC in China on 31 December 2019 [1]. Since then, novel coronavirus infection (COVID) has spread worldwide, causing a pandemic by March 2020 [2], affecting more than 200 countries. SARS-CoV-2 is a single strand enveloped RNA virus likely zoonotic in origin causing person-to-person transmission via respiratory large droplets and contact with infected surfaces [3,4]. COVID-19 spectrum ranges from asymptomatic carrier state to mild upper respiratory tract (URI) symptoms to severe disease encompassing ARDS and multisystem failure eventually leading to death. The infection is primarily affecting the elderly population as well as individuals with hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Young healthy adults with no underlying comorbidities are presumably at lower risk of developing severe disease [5].

2. Case

A 31-year-old African American female with morbid obesity, previous history of childhood asthma, and cutaneous psoriasis presented with 1 week of severe dyspnea on exertion, cough, subjective fever, chills and myalgias. She had attended a funeral along with a large group of individuals from multi-state areas 10 days prior to presentation. She had been exposed to a neighboring state co-worker suffering from seasonal allergies but otherwise had no recent travel or pet exposure.

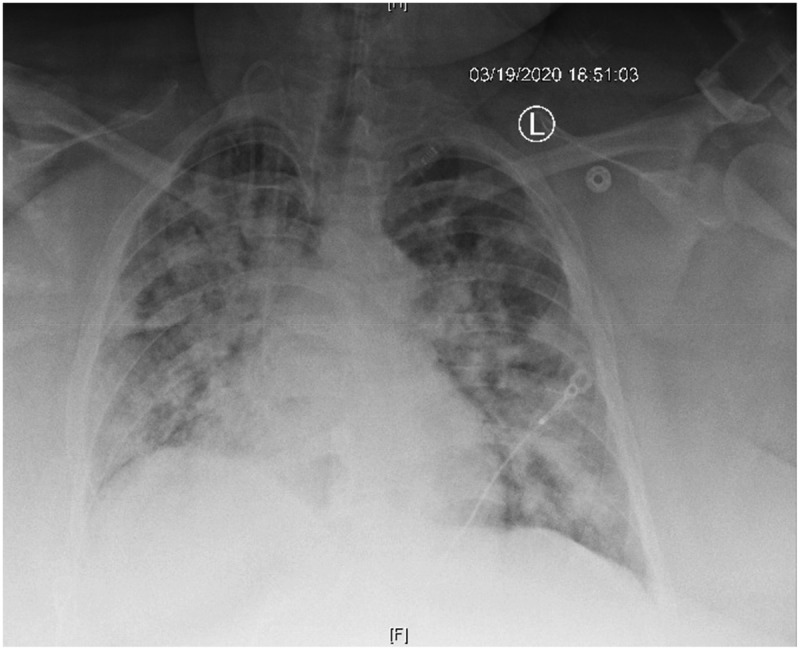

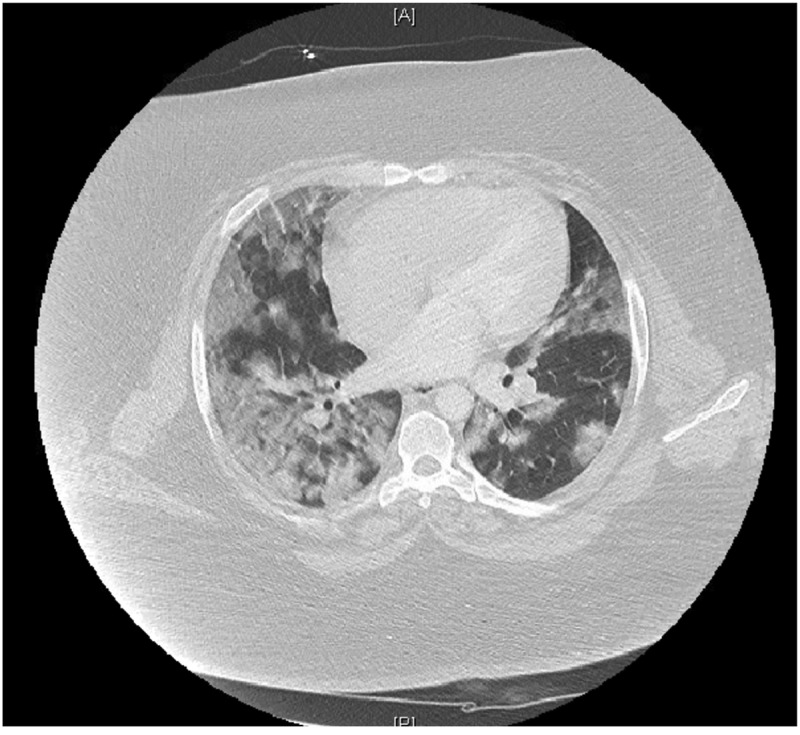

On presentation, she had high-grade fever of 103 F as well as tachypnea and hypoxemia requiring 3 L/min of supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula. On examination, diffuse pulmonary wheezing was present. BMI was recorded as 62.61 kg/m2. Imaging showed bilateral diffuse ground glass pulmonary infiltrates (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Laboratory parameters showed mild lymphopenia with normal total white blood cell count, normal platelet count, mild transaminitis, acute kidney injury as well as elevated C-reactive protein, ferritin, LDH and D-dimer but low procalcitonin. Interleukin-6 levels were markedly elevated to 76 pg/ml (Table 1). Nasopharyngeal respiratory pathogen PCR panel was negative. Nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral PCR was positive. The patient remained on supplemental oxygen replacement. Rapidly progressive hypoxemia ensued necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilatory support within 16 hours of presentation. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin were initiated. Significant-elevated positive-end-expiratory pressure and fraction of inspired oxygen were required for acceptable oxygenation consistent with ARDS. Prone ventilation attempts were unsuccessful. Tocilizumab, an interleukin (IL)-6 antagonist, was administered on day 3. IL-6 serum levels were significantly elevated, consistent with the cytokine release syndrome as the underlying mechanism of lung injury. Given shock and vasopressor-dependency, compassionate use of a novel anti-viral drug, Remdesivir, was not possible. Refractory hypoxemia subsequently led to the patient’s demise.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray illustrating severe bilateral multi-lobar infiltrates.

Figure 2.

CT Chest with contrast illustrating bilateral multi-lobar ground glass opacities.

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters during hospitalization.

| Test | Reference Range | Admission | Last Day |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (x10^9/L) | 4.4–10.7 | 5.7 | 10.5 |

| Absolute Lymphocyte count | 20–43% | 20.2 | 7.3 |

| BUN/Cr | 6–20 mg/dl,0.57–1 mg/dl | 10/1.17 | 54/3.99 |

| AST | 5–34 U/L | 66 | NA |

| ALT | 0–61 U/L | 41 | NA |

| LDH (IU/L) | 125–220 U/L | 827 | NA |

| Ferritin | 5–204 ng/mL | 527 | NA |

| CRP | <0.50 mg/dL | 8.01 | NA |

| D-dimer | 0.27–0.5 ug/mL | 1.40 | NA |

| Procalcitonin | <0.10 ng/mL | 0.07 | NA |

| IL-6 | 0.0–15.5 pg/mL | 76.7 | NA |

3. Discussion

Based on the initial data from Wuhan, China, COVID seemed to predominantly affect the elderly population and individuals with underlying chronic health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and chronic lung disease [6]. As COVID is now affecting the US, morbid obesity and race may be additional risk factors predicting severity of COVID-related illnesses, perhaps even serving as prognostic indicators of mortality. Indeed, the retrospective epidemiological analysis from Wuhan, China could not account for these risk factors. In China, morbid obesity is only seen in 6.3% of men whereas hypertension prevalence is 32.5% [7], diabetes mellitus 14.7% [8], and chronic obstructive lung disease 13.6% [9]. Moreover, it is estimated that 1 in every 5 Chinese individual has cardiovascular disease [10]. Comparatively, in the US, the prevalence of morbid obesity in the general population is 42.4% [11]. In the US, New York and Louisiana have been severely affected. In these states, the prevalence of morbid obesity is 27.6% and 37.8% whereas the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is 11% and 14%, respectively [12,13].

Moreover, in the US, race may be another risk factor as a higher mortality rate has been observed in both African Americans and Hispanics as compared to Caucasians. Although accounting for 33% of the population of Louisiana, 60% [14] of the total COVID-related deaths were reported in people of African American descent [15]. In another analysis of the population in Louisiana, 76.9% of those affected with COVID were black, although in hospital mortality was similar for all races [16]. Similarly, in the state of New York, Hispanics and African Americans which comprise 36.8% of the population have accounted for 61% of total COVID-related deaths, compared to a mortality of 27.3% in Caucasians [17,18] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of COVID-19 infection in New York and Louisiana.

At SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital in St. Louis, 84% of those tested positive for COVID were African Americans, which comprise 47% of the total population in St. Louis city [19]. Racial disparity and its associated lower comparative socioeconomic status and healthcare service utilization likely play a major role in poorer outcomes, as suggested in a recent publication [20]. A genetic predisposition leading to increased severity of infection from altered immunological responses cannot be excluded to explain this phenomenon.

A subgroup of individuals with severe COVID-19 infection have a cytokine release syndrome characterized by hyper-cytokinemia, hyper-ferritinemia, unremitting fever, and pulmonary involvement leading to ARDS, which can be seen in approximately 50% of patients [23]. A recent multicenter study of 150 confirmed cases in Wuhan, China, showed significantly elevated ferritin (>1000 ng/mL) and IL-6, suggesting a virus-driven hyperinflammation syndrome leading to devastating consequences and death [24]. A randomized control trial of tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antibody, has shown to improve mortality in COVID-19 pneumonia. All patients with COVID-19 should be screened for hyperinflammation using laboratory serial parameters such as elevated ferritin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, and decreased platelet counts as well as assessment of multi-organ dysfunction.

The originally described ‘classic’ risk factors associated with COVID will likely be expanded as further worldwide studies may reveal other population types at risk of developing the cytokine release syndrome. Thus far, we suspect that morbid obesity and race have both been under-represented in currently available epidemiological studies.

4. Conclusion

Since the beginning of the pandemic and our case presentation, there have been new developments in the available therapeutic strategies for COVID-19. Convalescent plasma, containing antibodies from recovered donors, has been approved for investigational use with an ongoing national multicenter trial to determine its efficacy [25–27]. Remdesivir, a viral RNA polymerase inhibitor with activity against other coronaviruses, has been reported to decrease the duration of illness [28]. Contrary to initial reports, corticosteroid use has been shown to reduce mortality as well as the duration of hospital stay when used during the inflammatory secondary phase of the illness approximately 7–10 days after the infection which is usually characterized by hypoxic respiratory failure [29]. Hydroxychloroquine, with or without azithromycin, have gone out of favor as therapeutic options for COVID [30]. In our hospital, we no longer use these medications; we have established a convalescent plasma program and have now begun using Remdesivir as well as adjuvant corticosteroids.

Although initial risk indicators for severe COVID infection, advanced age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus as well as cardiovascular and lung diseases may not be the only predictors of morbidity and mortality. In the US, morbid obesity and race, notably African Americans, seem to be associated with increased severity of disease and the COVID cytokine release syndrome.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf Who.int. 2020. [online]. Accessed on 14 June 2020. Available from:

- [2]. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 Who.int. 2020. WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks At The Media Briefing On COVID-19 - 8 June 2020. Accessed on 14 June 2020. Available from:

- [3].Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel. Forthcoming. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30251-8/fulltext

- [4].Infection Prevention and Control of Epidemic- and Pandemic-Prone Acute Respiratory Infections in Health Care . 1970. January 1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK214359/ [PubMed]

- [5].Guan W-J, Grein J, Zhang Y, et al.; China Medical Treatment Expert Group . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China: NEJM. 2020. March 27. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- [6].Wu Z, McGoogan JM.. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020. February 24;323(13):1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lewington S, Lacey B, Clarke R, et al.; China Kadoorie Biobank Consortium . The burden of hypertension and associated risk for cardiovascular mortality in China. 2016. April. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26975032?dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PubMed]

- [8].Hu C, Jia W.. Diabetes in China: epidemiology and genetic risk factors and their clinical utility in personalized medication. 2018. January 1. Available from: https://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/67/1/3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- [9].Fang L, Gao P, Bao H, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a nationwide prevalence study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(6):421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. https://www.world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Cardiovascular_diseases_in_China.pdf World-heart-federation.org. 2020 [online]. Accessed on 14 June 2020. Available from:

- [11].Adult Obesity Facts . 2020. February 27. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

- [12]. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/state/NY America's Health Rankings. 2020. Explore Health Measures In New York | 2019 Annual Report. [online]. Accessed on 14 June 2020. Available from:

- [13]. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/state/LA America's Health Rankings. 2020. Explore Health Measures In Louisiana | 2019 Annual Report. [online]. Accessed on 14 June 2020. Available from:

- [14]. http://ldh.la.gov/Coronavirus/ Available from:

- [15]. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/14/opinion/coronavirus-racism-african-americans.html Nytimes.com. 2020. Opinion | Why Coronavirus Is Killing African-Americans More Than Others [online]. Available from:

- [16].Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, et al. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. DOI: 10.1056/nejmsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NY Census Bureau QuickFacts. 2020. U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts: New York. [online] Available from:

- [18]. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04082020-1.pdf Www1.nyc.gov. 2020. [online] Available from:

- [19]. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/st-louis-population/ Worldpopulationreview.com. 2020. [online] Available from:

- [20].Chowkwanyun M, Reed AL.. Racial health disparities and Covid-19 — caution and context. N Engl J Med. 2020. DOI: 10.1056/nejmp201291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/hypertension/ The State of Childhood Obesity. 2020. Hypertension In The United States - The State Of Childhood Obesity. [online] Available from:

- [22]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/761348/copd-prevalence-us-by-state/ Statista. 2020. Prevalence Of COPD U.S. By State 2017 | Statista. [online] Available from:

- [23].Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020. (cytokine storm link). DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020. March 16;395(10229):1033–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Research, C. for B. E. Recommendations for investigational COVID-19 convalescent plasma. FDA; 2020. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/investigational-new-drug-ind-or-device-exemption-ide-process-cber/recommendations-investigational-covid-19-convalescent-plasma [Google Scholar]

- [26].Convalescent plasma therapy - Mayo Clinic . Forthcoming. [cited 2020 May26]. www.mayoclinic.org website. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/convalescent-plasma-therapy/about/pac-20486440

- [27].COVID-19 survivors needed to donate blood plasma. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis; 2020. April 16 [cited 2020 May26]. Available from: https://medicine.wustl.edu/news/covid-19-survivors-needed-to-donate-blood-plasma/ [Google Scholar]

- [28].Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020. DOI: 10.1056/nejmoa2007764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].CHEST - export citations. Journal.Chestnet.Org. Forthcoming. [cited 2020 May26]. Available from: https://journal.chestnet.org/action/showCitFormats?pii=S0012-3692%2815%2950745-9&doi=10.1378%2Fchest.129.6.1441

- [30].Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. DOI: 10.1056/nejmoa2012410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]