Abstract

Prostate cancer innervation contributes to the progression of prostate cancer (PCa). However, the precise impact of innervation on PCa cells is still poorly understood. By focusing on muscarinic receptors, which are activated by the nerve-derived neurotransmitter acetylcholine, we show that muscarinic receptors 1 and 3 (m1 and m3) are highly expressed in PCa clinical specimens compared to all other cancer types, and that amplification or gain of their corresponding encoding genes (CHRM1 and CHRM3, respectively) represent a worse prognostic factor for PCa progression free survival. Moreover, m1 and m3 gene gain or amplification are frequent in castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) compared with hormone-sensitive PCa (HSPC) specimens. This was reflected in HSPC-derived cells, which show aberrantly high expression of m1 and m3 under androgen deprivation mimicking castration and androgen receptor inhibition. We also show that pharmacological activation of m1 and m3 signaling is sufficient to induce the castration-resistant growth of PCa cells. Mechanistically, we found that m1 and m3 stimulation induces YAP activation through FAK, whose encoding gene, PTK2 is frequently amplified in CRPC cases. Pharmacological inhibition of FAK and knockdown of YAP abolished m1 and m3-induced castration-resistant growth of PCa cells. Our findings provide novel therapeutic opportunities for muscarinic-signal-driven CRPC progression by targeting the FAK-YAP signaling axis.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Castration resistance, Innervation, Muscarinic receptor, FAK, Hippo, YAP

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and second most frequent cause of cancer related death among men in the US, which accounts for 10% of all estimated new deaths of cancer among men [1]. More than 95% of PCa is originally sensitive to androgen deprivation therapy, namely surgical castration, pharmacological castration, and androgen receptor (AR) inhibitors; however, PCa eventually gains resistance to these hormonal therapy [2]. This state is referred to as castration-resistant PCa (CRPC). Several treatment options such as new generation AR inhibitors, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunomodulatory agents were newly approved for CRPC in this decade, however CRPC is still poorly controlled and often a fatal disease.

A recent breakthrough in PCa basic research was the discovery of the contribution of nerves in stromal tissues in the progression of PCa [3–5]. Stromal adrenergic fibers were shown to induce early phase development of PCa, while cholinergic fibers induce invasion and metastasis of PCa [5]. This is consistent with several clinical findings: spinal cord injured patients have lower incidence of PCa [6, 7], β-blocker users have reduced PCa-specific mortality in patients with high-risk or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [8], and the incidence rates of prostate cancer decreases with increasing cumulative dose of anti-muscarinic agents for overactive bladder [9]. However, the direct effects of innervation on cancer cells are still unclear. A previous study showed autocrine activation of cholinergic receptor muscarinic 3 (CHRM3) in PCa cells [10]; yet, the precise mechanisms of muscarinic signaling on PCa cells are poorly defined.

In this study, we characterized the expression of cholinergic receptor muscarinic 1 (CHRM1; m1) and CHRM3 (m3) receptors in hormone-sensitive PCa (HSPC) and CRPC clinical specimens and PCa-derived cell lines, to determine how signaling by these receptors affect growth under castrated conditions. We next dissected downstream signaling of these receptors to identify new druggable targets. We show that m1 or m3 activation induce the castration resistant growth of PCa cells, and that this process requires the activation of YAP, a transcriptional co-activator regulated by the Hippo pathway. In turn, we found that m1 and m3 receptors stimulate YAP through the focal adhesion kinase (FAK). Pharmacological inhibition of FAK prevented YAP activation induced by m1 and m3 receptors, and consequently inhibited castration resistant growth of PCa cells. Overall, our results suggest that FAK represents as potential therapeutic target for the treatment of innervation-driven castration resistant growth of PCa.

Results

Transcripts for m1 and m3 are upregulated in PCa, and their genes are frequently amplified or gained in CRPC

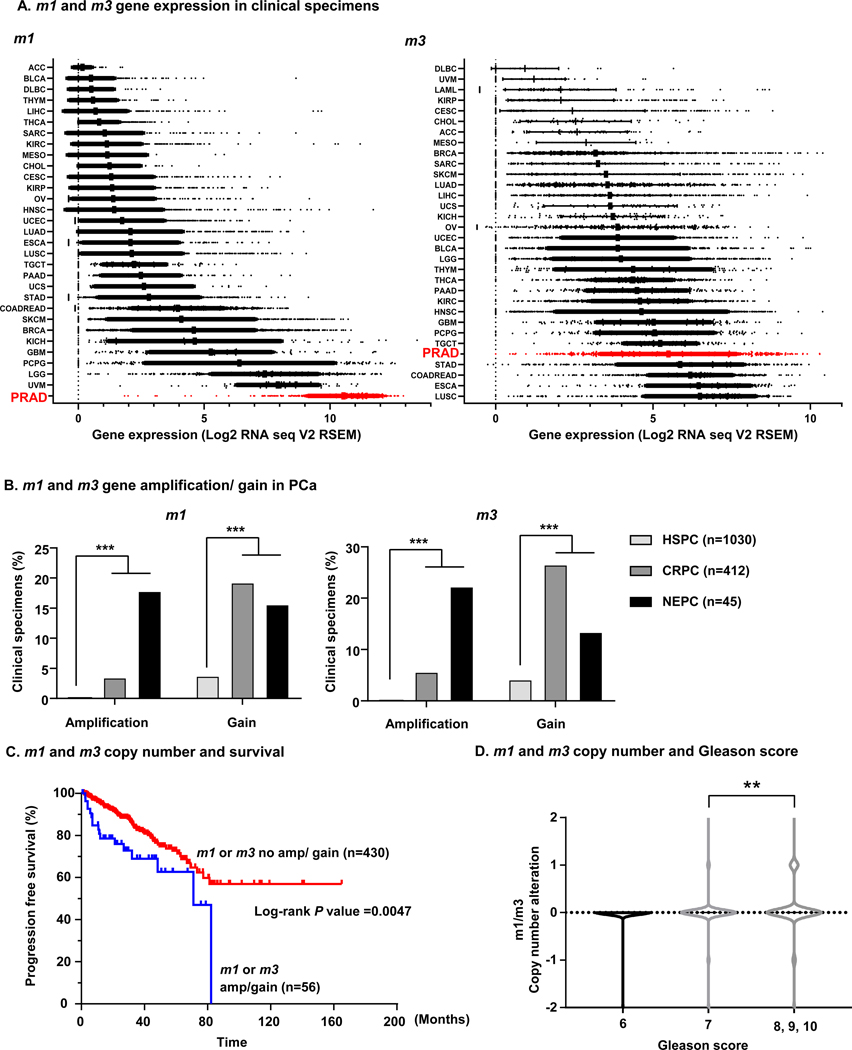

To explore the importance of m1 and m3 in PCa, we first investigated m1 and m3 mRNA expression in The Cancer Gene Atlas (TCGA) pan cancer expression analysis by RNA-seq, including 31 different cancer types and 10858 clinical specimens. Compared to all other cancer types, prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) had the highest expression of m1, and fifth highest expression of m3 (Fig. 1A). Since CRPC is a clinically challenging condition of PCa and TCGA-PRAD samples are all classified as HSPC, we next combined 12 different clinical cohorts consisting of 1487 prostate cancer specimens to analyze copy number alterations (CNA) as PCa gains hormone resistance, namely, HSPC, CRPC and neuroendocrine PCa (NEPC), the latter a highly aggressive form of CRPC. Remarkably, m1 amplification or gain were significantly frequent in CRPC and NEPC (P < 0.001), and m3 amplification or gain were also significantly frequent in CRPC and NEPC (P < 0.001) compared to HSPC specimens (Fig. 1B). We also performed a cross-cancer analysis approach with 52438 clinical tissues for m1 and m3 copy number alterations, and found that several PCa cohorts have high amplification frequency of m1 and m3 among 184 cohorts (Supp. Fig.1A and 1B). Of interest, we found that the expression of m1 and m3 is significantly higher when compared with other muscarinic receptors (m2, m4, and m5) in PCa tissues (Supp. Fig.1C). Furthermore, m1 and m3 amplification or gain represent a worse prognostic factor for progression free survival of PCa patients (Fig. 1C). When we stratify patients by Gleason score, which is a histological grade based on PCa tissue histology, patients with aggressive PCa whose Gleason score were 8, 9 or 10 have significantly higher copy number alteration compared to the patients with Gleason score 7 patients (Fig. 1D). These findings suggest a possible oncogenic role for m1 and m3 receptors in PCa, especially CRPC.

Figure 1. Frequent overexpression of m1 and m3 in PCa and gene amplification and gain in CRPC.

A, Pancancer analysis of m1 and m3 expression. n = 10858. Red indicates patients with prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD). ACC; Adrenocortical Carcinoma (n = 79), BLCA; Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma (n = 427), BRCA; Breast Invasive Carcinoma (n = 1218), CESC; Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Endocervical Adenocarcinoma (n = 310), CHOL; Cholangiocarcinoma (n = 45), COADREAD; Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (n = 666), DLBC; Lymphoid Neoplasm Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (n = 48), ESCA; Esophageal Carcinoma (n = 196), GBM; Glioblastoma Multiforme (n = 174), HNSC; Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (n = 566), KICH; Kidney Chromophobe (n = 91), KIRC; Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma (n = 606), KIRP; Kidney Renal Papillary Cell Carcinoma (n = 323), LGG; Brain Lower Grade Glioma (n = 534), LIHC; Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (n = 486), LUAD; Lung Adenocarcinoma (n = 576), LUSC; Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (n = 554), MESO; Mesothelioma (n = 25), OV; Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma (n = 309), PAAD; Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (n = 183), PCPG; Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (n = 187), PRAD; Prostate Adenocarcinoma (n = 550), SARC; Sarcoma (n = 265), SKCM; Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (n = 474), STAD; Stomach Adenocarcinoma (n = 412), TGCT; Testicular Germ Cell Cancer (n = 156), THCA; Thyroid Carcinoma (n = 572), THYM; Thymoma (n = 122), UCEC; Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma (n = 567), UCS; Uterine Carcinosarcoma (n = 57), UVM; Uveal Melanoma (n = 80). B, Gene copy number gain and amplification of m1 and m3 are prominent in CRPC and NEPC compared to HSPC. HSPC (n = 1030), CRPC (n = 412), NEPC (n = 45). ***P < 0.001 (Fisher’s exact test). C, m1/ m3 gene amplification or gain is a worse prognosis factor for progression free survival in PCa patients. Kaplan-Meier survival curve depicting progression free survival for PCa patients stratified against gene copy number alterations of m1 and m3. TCGA-PRAD patients available for progression free survival data (n = 486) were divided into two groups; patients with m1 gene amplification or gain, or m3 gene amplification or gain (n = 56); patients without gene amplification or gain for m1 or m3 (n = 430). P = 0.0047 (Log-rank test). D, High Gleason score is associated with high copy number alteration of m1 and m3. TCGA-PRAD patients are classified by Gleason score; 6, 7, or 8/ 9/ 10. Patients with Gleason score 8/ 9/ 10 have increased gene copy number change in m1 or m3 compared to patients with Gleason score 7. **P < 0.01 (One-way ANOVA).

m1 and m3 are highly expressed in CRPC cell lines, and activation of m1 and m3 is sufficient to induce castration resistant growth of PCa cells

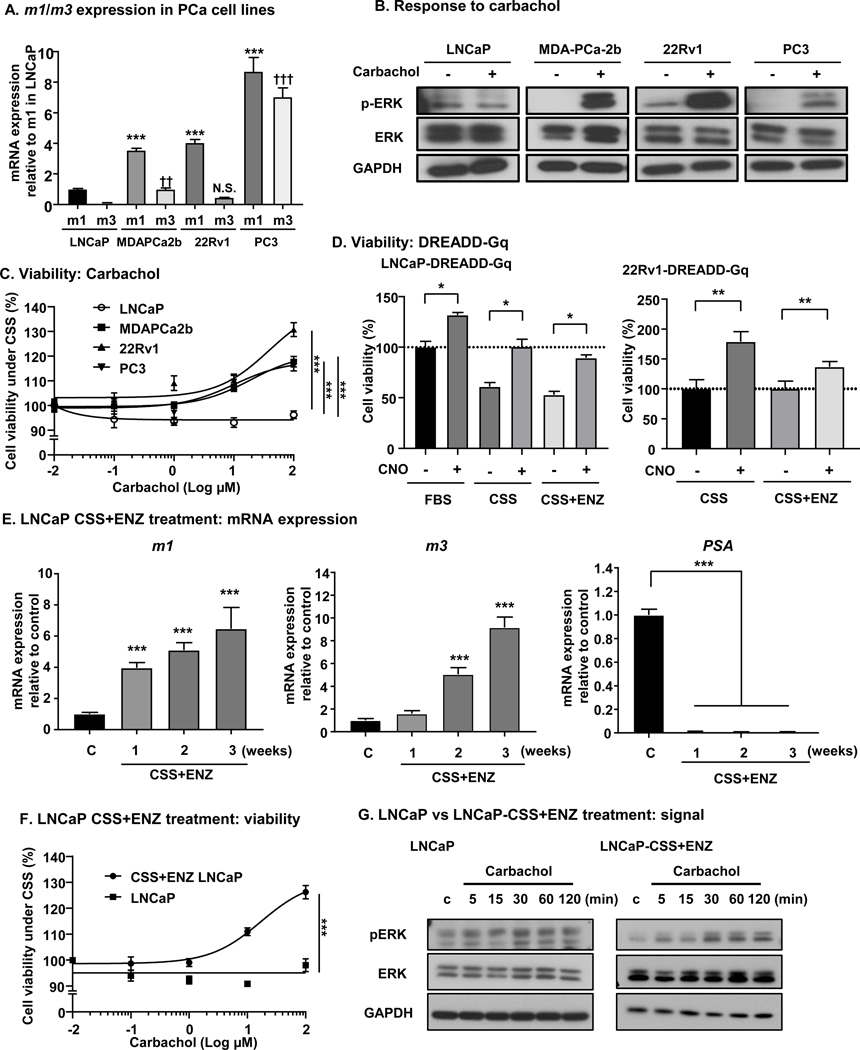

We next investigated expression of m1 and m3 in PCa cell lines. We used LNCaP cell line as a typical castration and AR inhibitor sensitive cell line, and MDAPCa2b as a castration sensitive, but AR inhibitor resistant cell line [11]. As CRPC cell lines, we used 22Rv1 which expresses AR, and PC3 which does not express AR [12]. qPCR analysis of m1 and m3 revealed increase of m1 and m3 expression progressively as the cells become resistant to castration or AR inhibitors (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we performed immunofluorescence for m1 and m3 protein in these cell lines, which showed that m1 and m3 protein expression levels increase as cells become castration resistant, similar to mRNA levels (Supp. Fig. 1D). Consistent with these data, pharmacological activation of m1 and m3 by a synthetic muscarinic agonist carbachol for 5 minutes showed rapid pERK (T202/ Y204) elevation in MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1, and PC3, but not in LNCaP (Fig. 2B and Supp. Fig. 2A). Since early studies have suggested that m1 and m3 may exert oncogenic roles [13], we stimulated these cells with different concentrations of carbachol under castrated conditions (charcoal stripped serum; CSS) [14]. Of interest, carbachol induced increase of viability in MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1 and PC3, but not in LNCaP (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. m1 and m3 are upregulated in CRPC cell lines, and activation of m1 and m3 induces castration resistant growth of PCa cells.

A, mRNA expression levels of m1 and m3 in 4 different PCa cell lines (LNCaP, MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1 and PC3) measured by qPCR. GAPDH was used for normalization. Compared to LNCaP, MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1, and PC3 had significantly higher mRNA expression of m1. ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). MDAPCa2b and PC3 had significantly higher mRNA expression of m3 compared to LNCaP. ††P < 0.01, †††P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). Bars represent average plus standard error of the mean (SEM) (N = 4). B, Differential response to carbachol measured by pERK expression (pT202/ Y204). Cells are incubated with 100 μM carbachol for 5 min, and subjected to Western blotting. MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1, and PC3 showed increase in pERK with carbachol, but no increase was observed for LNCaP. C, Cell viability in response to carbachol. PCa cells were treated with different concentrations of carbachol for 72 hours. LNCaP did not respond to carbachol, but MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1, and PC3 showed an increase in viability with carbachol. Bars represent average ±SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). D, Cell viability in response to CNO for LNCaP-DREADD-Gq and 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells. One μM of CNO induced increase in cell vitality under 10% FBS, 5% CSS, 5% CSS + 10μM ENZ condition for LNCaP-DREADD-Gq cells, and 1μM of CNO induced increase in cell vitality under 5% CSS, 5% CSS + 10 μM ENZ condition for 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (One-way ANOVA). E, m1, m3, and PSA mRNA expression under CSS + ENZ. LNCaP cells are treated with 5% CSS + 10 μM ENZ for indicated time. m1 or m3 expression increased, and PSA decreased in a time-dependent fashion. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P <0.001 (One-way ANOVA). F, Cell viability in response to carbachol before and after CSS + ENZ treatment. After 1 week of 5% CSS + 10 μM ENZ, cells are subjected to viability assay. CSS + ENZ treated cells increased viability with carbachol, but no response was seen for cells under basal conditions cells. Bars represent average ± SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). G, Response to carbachol before and after CSS + ENZ in LNCaP. pERK increase was seen in CSS + ENZ treated LNCaP with 100μM carbachol, but no difference in pERK was observed for LNCaP cells under basal conditions.

As both m1 and m3 are G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are coupled to Gαq, we engineered PCa cell lines stably expressing a synthetic Gq-coupled GPCR (DREADD-Gq) for LNCaP and 22Rv1; LNCaP-DREADD-Gq and 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq, respectively. This DREADD-Gq was developed based on the m3 receptor, and is mutated so that it cannot be activated by its natural ligand (acetylcholine), but gained the ability to be activated only by a synthetic ligand, Clozapine N-oxide (CNO) [15]. This synthetic biology system can circumvent the known variability of GPCR expression levels and the presence of potential autocrine loops that would result in variable basal GPCR activity, and consequently, it can facilitate the analysis of the effects of Gq activation in PCa cells. Treatment with CNO in LNCaP-DREADD-Gq cells induced increased cell viability under FBS medium, CSS medium as well as in CSS + enzalutamide (ENZ) medium. Similarly, CNO treatment in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells showed increase in viability under the same conditions, CSS medium, and CSS + ENZ medium (Fig. 2D). These data support that activation of Gq signaling in cancers by m1 and m3 stimulation can induce castration resistant growth of PCa cells.

Next, we tested m1 and m3 expression in LNCaP cells after treatment with CSS + ENZ. Treatment of LNCaP cells with CSS + ENZ for up to 3 weeks resulted in a time-dependent increase of m1 and m3, and decrease of prostate specific antigen (PSA) (Fig. 2E). We next asked if these CSS + ENZ treated cells can respond to carbachol in terms of viability under androgen deprivation mimicking castration. As shown in Fig. 2F, 1 week treated LNCaP (CSS+ENZ-LNCaP) cells gained the ability to grow with carbachol. Mechanistically, we investigated the activation of ERK as measured by pERK accumulation after stimulation by carbachol, and found that CSS+ENZ-LNCaP cells could respond to carbachol in a dose-dependent manner as shown by increase in pERK, but no response was observed in wild-type LNCaP cells (Fig. 2G and Supp. Fig. 2B). To dissect the role of m1 and m3 in mitogenic signaling, we used siRNAs for m1 and m3 to knockdown each receptor, using PC3 cells that show high m1 and m3 expression compared to other cell lines (Fig. 2A). Knockdown of m1 and m3 showed reduction of pERK in response to carbachol (Supp. Figs. 3A – 3C). Furthermore, to investigate the effect of activation of other GPCRs, we stimulated LNCaP cells with LPA and thrombin, which showed a slight increase in pERK signal, similar to the response to carbachol (Supp. Figs. 4A and 4B). Our recent study confirmed that DREADD Gq is primarily selective for Gq proteins, similar to m1 and m3 [16]. However, to examine the possible contribution of β-Arrestins to Gq-mediated mitogenic signaling, we knocked down β-Arrestin 1/ 2 in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells, and stimulated with CNO. As shown in Supp. Figs. 4C and 4D, knockdown of β-Arrestin did not change pERK levels induced by CNO, which suggests β-Arrestin may not contribute the Gq mediated mitogenic signaling in PCa cells. Together, these results support that stimulation of m1 and m3 receptors can support the castration resistant growth of PCa cells.

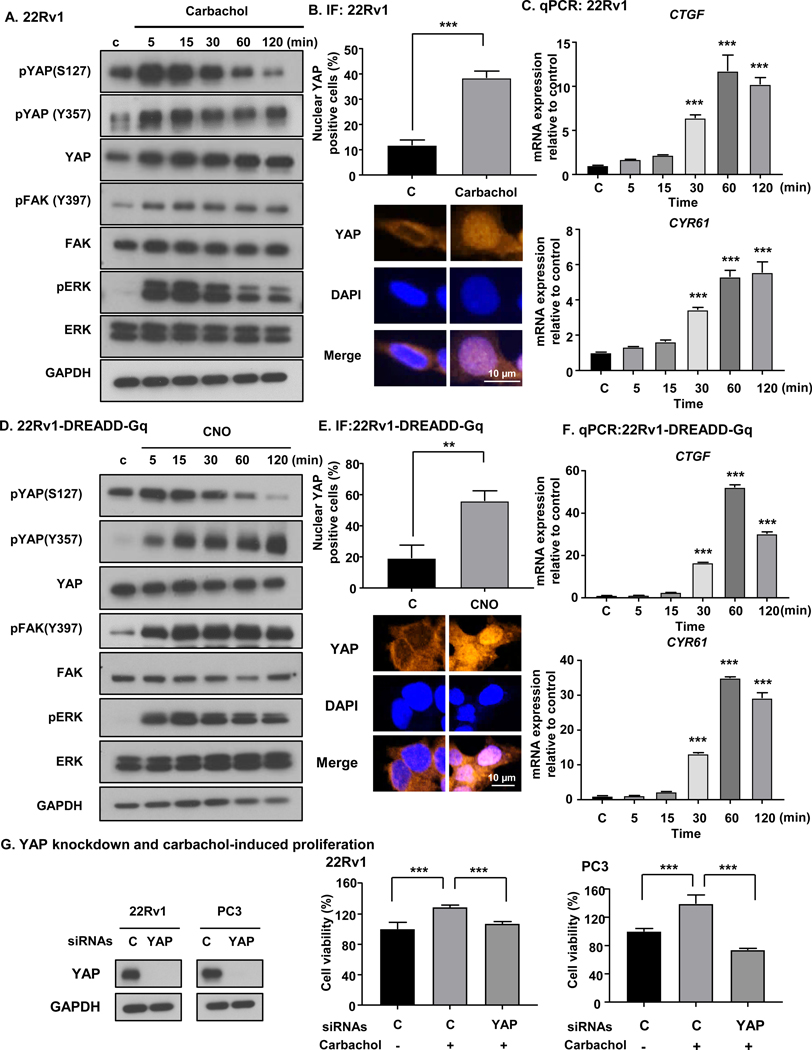

Oncogenic m1 and m3 signaling activates FAK and YAP

We have recently reported YAP activation through FAK by Gq signaling promoted by the GNAQ oncogene, encoding constitutively active Gαq, in uveal melanoma [17]. Thus, we hypothesized m1 and m3 stimulation could induce FAK and YAP activation by a similar mechanism in PCa. After treatment with carbachol, 22Rv1 cells showed clear activation of YAP, which was assessed by decrease of serine phosphorylated YAP (S127), and increase of tyrosine phosphorylated YAP (Y357) (Fig. 3A and Supp. Fig. 5A). Consistent with these results, immunofluorescence (IF) assay for YAP showed nuclear translocation of YAP after treatment with carbachol (Fig. 3B). In addition, qPCR analysis showed upregulation of CTGF and CYR61, which are typical YAP-regulated genes, after carbachol stimulation (Fig. 3C). Concomitantly, we could also see the increase of pFAK (Y397), the active tyrosine phosphorylated form of FAK [17], with carbachol stimulation; as a canonical pathway by Gq signaling, we confirmed elevation of pERK by carbachol (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. m1 and m3 signaling activate FAK and YAP, resulting in castration resistant growth.

A, Carbachol induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and YAP activation in 22Rv1 cells. 22Rv1 cells were stimulated by 100 μM of carbachol over time, and subjected to western blotting analysis. B, Carbachol (100 μM) induced nuclear translocation of YAP. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). C, Carbachol (100 μM) induced CTGF and CYR61 mRNA expression, which are downstream targets of YAP. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). D, CNO (1 μM) induced FAK and YAP activation in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells. E, CNO (1 μM) induced nuclear translocation of YAP in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). F, CNO (1 μM) induced CTGF and CYR61 mRNA expression in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). G, YAP knockdown and carbachol-induced proliferation. YAP knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blot. In 22Rv1 and PC3, YAP knockdown prevented the increased cell viability in response to carbachol. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA).

We hypothesized that FAK-YAP activation might explain castration resistant growth of 22Rv1 cells with stimulation by muscarinic receptor agonist. To confirm that FAK-YAP activation is induced by activation of Gq signaling, we took advantage of our 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells for these assays. CNO treatment induced a decrease of serine phosphorylation of YAP (S127), coupled to increase of tyrosine phosphorylation of YAP (Y357), and increase of pFAK and pERK (Fig. 3D and Supp. Fig. 5B). IF assay showed an increase in nuclear YAP positive cells after treatment with CNO (Fig. 3E), and CTGF and CYR61 upregulation after CNO stimulation (Fig. 3F). In line with these findings, LNCaP-DREADD-Gq treated with CNO and MDAPCa2b with carbachol induced FAK-YAP activation (Supp. Fig. 6). Together, these findings suggest that m1 and m3 activate FAK and YAP, and that this may provide a mechanism for castration resistant growth induced by m1 and m3 activation.

Next, we asked if YAP knockdown is sufficient to rescue the effect of castration resistant growth of PCa cells. After confirming knockdown efficiency using siRNAs targeting YAP (si-YAP), we knocked down YAP in 22Rv1 and PC3 together with carbachol stimulation. As shown in Fig. 3G and Supp. Fig. 7A, YAP knockdown reverted the effect of carbachol on castration resistant growth. This suggests that YAP functions as a key effector for castration resistant growth induced by m1 and m3 stimulation.

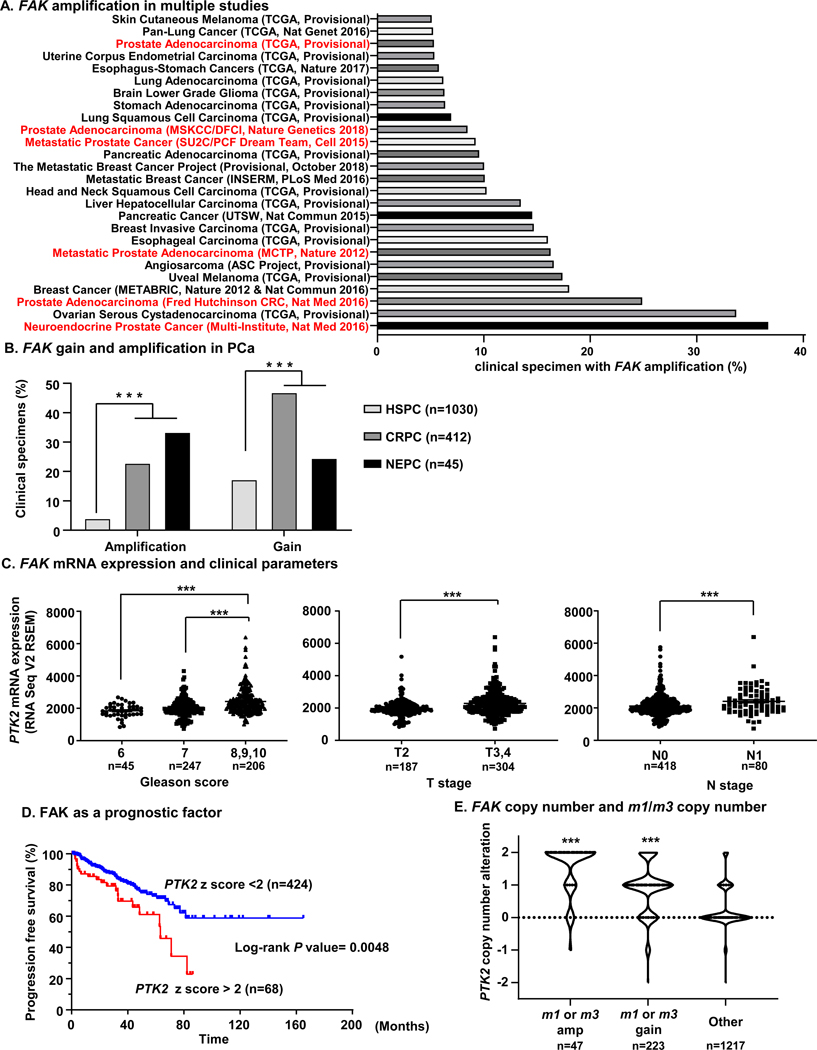

PTK2, the FAK gene, is frequently amplified and gained in CRPC, and m1 or m3 amplified patients harbor frequent FAK gene copy number increase

As we found that FAK-YAP activation can provide a mechanism for castration resistant growth of PCa cells induced by m1 and m3 activation, we next investigated the relevance of FAK in clinical PCa specimens. First, we applied a cross-cancer approach with 52438 clinical tissues to investigate CNAs in the gene encoding FAK, PTK2 (herein referred as FAK). Among them, FAK copy number data were available for 20531 tissues, in which we assessed FAK amplification frequency in different cohorts. Among 184 cohorts, 26 cohorts showed FAK amplification more than 5%. Interestingly, 6 cohorts with PCa patients (Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer, Multi-Institute, Nat Med 2016; Prostate Adenocarcinoma, Fred Hutchinson CRC, Nat Med 2016; Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma, MCTP, Nature 2012; Metastatic Prostate Cancer, SU2C/PCF Dream Team, Cell 2015; Prostate Adenocarcinoma, MSKCC/DFCI, Nature Genetics 2018; and Prostate Adenocarcinoma, TCGA, Provisional) were ranked as highly amplified cohorts (Fig. 4A). We next asked whether FAK CNA correlates with castration-resistance, for which 1487 PCa samples were subjected to analysis for FAK gene amplification or gain. Remarkably, FAK amplification was more frequent in CRPC and NEPC than in HSPC, and FAK gain was also more frequent in CRPC and NEPC than in HSPC (Fig. 4B). Moreover, FAK expression was significantly higher in patients with more aggressive disease, measured by a Gleason score of 8, 9, or 10 compared to patients with Gleason score of 6 or 7. Similarly, FAK expression was significantly higher in patients with larger tumors, T3 and T4, as compared with T2, and higher in patients with lymph node invasion, N1, when compared with patients in which no lymph node invasion was detected, N0 (Fig. 4C). Moreover, high expression of FAK was a worse prognostic factor for patients with PCa (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, patients with m1 or m3 amplification had more FAK copy number gains, and patients with m1 or m3 gain had higher FAK copy number, compared to patients without m1 and m3 amplification or gain (Fig. 4E). These data suggest a critical role of FAK in PCa progression, especially CRPC, and raise the possibility of an active role for m1-m3- FAK signaling in clinical PCa specimens.

Figure 4. Clinical impact of FAK gene expression on PCa.

A, Cross-cancer analysis with 52438 clinical tissues for FAK gene copy number alterations. In 184 studies with 20531 specimens that FAK copy number data were available, 26 cohorts showed FAK gene amplification in more than 5% of the cases. 6 cohorts (Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer, Multi-Institute, Nat Med 2016; Prostate Adenocarcinoma, Fred Hutchinson CRC, Nat Med 2016; Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma, MCTP, Nature 2012; Metastatic Prostate Cancer, SU2C/ PCF Dream Team, Cell 2015; and Prostate Adenocarcinoma, MSKCC/DFCI, Nature Genetics 2018; Prostate Adenocarcinoma, TCGA, Provisional) with PCa patients were ranked as highly FAK gene amplified cohorts. B, analysis of PCa cohorts (n = 1487) revealed that NEPC or CRPC specimens had significantly higher amplification or gain of the FAK gene compared to HSPC specimens. ***P < 0.001 (Fisher’s exact test). C, Association between mRNA expression of FAK, encoded by PTK2, and Gleason score, T stage and N stage in PCa. Higher mRNA expression of PTK2 was associated with higher Gleason score, T stage, and N stage. Patients with available clinical data and PTK2 mRNA data are extracted from TCGA-PRAD database, and divided into Gleason score 6 (n = 45), 7 (n = 247), and 8, 9, 10 (n = 206). Similarly, data-available cases are divided into T stage T2 (n = 187), and T3, T4 (n = 304), and into N stage N0 (n = 418) and N1 (n = 80). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). D, Progression free survival of PCa patients and PTK2 expression. Patients with higher expression of PTK2 (z score > 2) showed poorer outcome of progression free survival compared with patients with lower expression of FAK (z score < 2). Log-rank P = 0.0048. E, Comparison of FAK gene copy number alteration and m1 or m3 gene amplification, gain. In m1 or m3 gene amplified tissues (n = 47), or m1 or m3 gene gained tissues (n = 223), PTK2 copy number was significantly higher compared to other tissues (n = 1217). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA).

YAP is activated thorough FAK, and FAK inhibitor can inhibit carbachol induced castration resistant growth of PCa cells

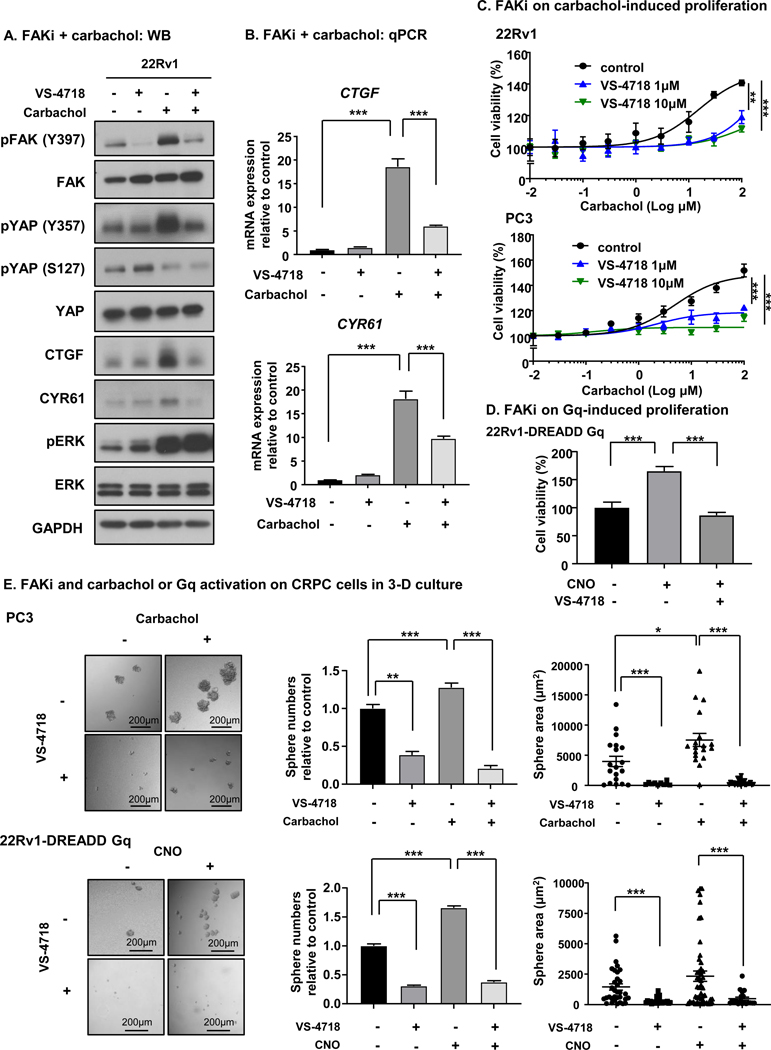

The impact of m1-m3 FAK-YAP signaling in PCa cells and specimens prompted us to evaluate the possibility of the pharmacological intervention on FAK as a therapeutic venue in CRPC. VS-4718, an orally available FAK inhibitor (FAKi) was used in this study. To study the effect of FAK inhibition on YAP signaling, we assessed whether FAKi could inhibit the activation of YAP induced by carbachol. 22Rv1 cells were treated with FAKi, carbachol or both. Carbachol treatment induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) and YAP (Y357), and CTGF and CYR61 elevation. These effects were abolished by the addition of FAKi; however, FAKi did not prevent an increase in pERK, suggesting that FAK does not affect canonical signaling downstream of Gq to ERK, consistent with our previous report [17] (Fig. 5A and Supp. Fig. 7B). Similarly, FAKi could block upregulation of CTGF and CYR61, which were induced by carbachol (Fig. 5B). Next, we tested the potential of FAK inhibition for CRPC treatment. We treated 22Rv1 and PC3 with carbachol with or without FAKi. Remarkably, FAKi blocked castration resistant growth of 22Rv1 and PC3 cells induced by carbachol (Fig. 5C). We also used 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells to investigate whether Gq activation by CNO and its induction of viability can be blocked by FAKi. Similar to the results with carbachol, the increase of viability in 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells by CNO was abolished by FAKi (Fig. 5D). Finally, we used cell sphere assays to study the effects of FAKi in conditions that better reflect the in vivo situation. FAKi could significantly block the sphere formation in PC3 and 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cell lines in terms of sphere number and area, and Gq stimulation by carbachol or CNO induced significantly higher number of spheres in PC3 and 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells, respectively. Furthermore, CNO or carbachol-induced sphere formation was abolished by co-administration of FAKi (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. Pharmacological inhibition of FAK blocks carbachol-induced YAP activation and proliferation.

A, Treatment with FAK inhibitor can block YAP activation induced by carbachol at the protein level. 22Rv1 cells are treated with 10 μM of VS-4718 for 2 hours, treated with 30 μM of carbachol for 1 hour, or both. Carbachol induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK (Y397), tyrosine phosphorylation of YAP (Y357), CTGF increase, and CYR61 increase, all of which were abolished by treatment together with VS-4718. pERK induction by carbachol was not blocked by VS-4718. B, FAK inhibitor can block CTGF and CYR61 increase induced by carbachol. 22Rv1 cells are treated with 10 μM of VS-4718 for 2 hours, treated with 30 μM of carbachol for 1 hour, or both. Carbachol induced increase of CTGF and CYR61 as measured by qPCR, and this increase was blocked by treatment together with VS-4718. Bars represent average + SEM (N = 4). ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). C, FAKi could block PCa cell proliferation induced by carbachol. 22Rv1 and PC3 cells were treated with VS-4718 with indicated concentration for 2 hours, and stimulated with different concentrations of carbachol for 72 hours. VS-4718 could block PCa cell proliferation induced by carbachol. Bars represent average ± SEM (N = 4). **P <0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). D, FAKi can block PCa cell proliferation induced by CNO. 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells were treated with 10 μM VS-4718, and stimulated with 1 μM CNO for 72 hours. VS-4718 could block PCa cell proliferation induced by CNO. Bars represent average ± SEM (N = 4). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA). E, Impact of FAKi on carbachol or Gq activation on CRPC cell sphere formation in 3-D culture. Gq stimulation by carbachol or CNO on DREADD-Gq induced significantly higher number of cell spheres in PC3 and 22Rv1-DREADD-Gq cells, respectively. FAKi could significantly reduce the 3-D growth (spheres) of both PC3 and 22Rv1 CRPC cells in terms of sphere number and area. Furthermore, CNO or Carbachol-induced sphere formation was abolished by co-administration of FAKi. Bars represent average ± SEM (N = 15). *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

Discussion

Muscarinic G-protein coupled receptors were first shown to possess ligand-dependent oncogenic function in 1991 [13]. In this early study, carbachol stimulation of m1, m3, and m5 receptors stably expressing NIH3T3 cells but not m2 and m4 receptors resulted in the ability to induce strong cellular transformation [13]. Since this initial discovery, alteration of G proteins and GPCRs by mutation or aberrant expression have been found to be involved in cancer initiation and progression across a wide range of cancer types [18, 19]. In PCa, a previous elegant innervation-driven tumor progression models using PC3 xenograft showed distant metastasis and poor survival outcome in Chrm1+/+ mice compared with Chrm1−/− mice [5]. In line with these findings, as an origin of neural signaling, it was reported that nerve progenitor cells from the subventricular zone of the mouse brain migrate into blood vessels, and give rise to nerve cells surrounding PCa cells [3]. These findings support the possibility of PCa progression through neural signaling, albeit the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms were not explored. Towards this end, we now show a direct pro-oncogenic effect of m1 and m3 receptor activation in PCa cells, especially contributing to the castration resistant growth of PCa, which is the most challenging state of PCa in the clinical setting.

We observed increased expression of m1 and m3 mRNA after CSS and enzalutamide treatment in LNCaP cells in a time dependent manner, concomitant with increased response to carbachol in terms of signaling and viability. This represents a gain of function upon AR inhibition, given that the original LNCaP cells do not respond to carbachol neither in regards to signaling nor in viability. Interestingly, using publicly available PCa datasets, we showed that m1 and m3 are amplified and gained in CRPC when compared to HSPC clinical specimen. This suggests that when hormone-sensitive PCa are treated with androgen deprivation therapy, the cancer cells may gain other signaling properties to survive in low-androgen condition, and that one of these critical signals may be provided by innervation-driven muscarinic receptor activation.

In this regard, the adaptive and compensatory mechanisms driving proliferation in PCa under androgen deprivation have been extensively studied. Such mechanisms that bypass AR signaling have been found to involve the activation of Src kinase [20, 21], glucocorticoid receptor [22], PI3K-PTEN signaling [23, 24], and FGFR-MAPK signaling [25]. As for muscarinic signaling, previous reports have shown that carbachol induced DNA synthesis and proliferation of PCa cells [10, 26–28], consistent with our data. In addition, several ligands for GPCRs were reported to promote mitogenic signaling in PCa, such as angiotensin, bombesin, bradykinin, and lysophosphatidic acid [29], many of which bind to and activate Gαq-coupled GPCRs. Interestingly, the blockade of Gq activation by Regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) was reported to block androgen independent growth of LNCaP cells [30]. Although how m1 and m3 are upregulated upon androgen deprivation is unclear, these changes can provide a novel mechanism driving castration resistant growth.

Mechanistically, we showed Hippo-YAP signaling axis is potently activated after stimulation of m1 and m3 with carbachol. Recently, the contribution of YAP to castration resistant growth has been reported by several studies. One study showed a direct interaction between YAP1 and AR that is modulated by MST1, and can be abolished by Verteporfin [31]. Furthermore, YAP has been found to be upregulated and activated in CRPC human tissues [32, 33]. Our results are consistent with these previous reports showing contribution of YAP to castration resistant growth, and we provide a novel link between innervation and the Hippo-YAP signaling axis in castration resistant growth of PCa. Verteporfin is the only drug approved by FDA that can target YAP by inhibiting the interaction between YAP and TEAD [31]. However, Verteporfin has high systemic toxicities after prolonged use [34], and recent studies have revealed an off-target activity of Verteporfin as an autophagosome inhibitor by promoting oligomerization of p62, which can explain its systemic toxicities [35–37]. In this context, the discovery of novel druggable targets for YAP-induced castration resistant growth of PCa is urgently needed. Our group recently reported FAK as one of the druggable targets against YAP activity in uveal melanoma, which has activating mutations in GNAQ or in GNA11.This previous work prompted us to hypothesize FAK as potential target for PCa proliferation induced by activated muscarinic receptors.

In this study, we showed that pharmacological inhibition of FAK could abolish the activation of YAP, and subsequent castration-resistant growth of PCa cells induced by carbachol treatment. Remarkably, we found that FAK is frequently amplified and gained in CRPC clinical tissues, and that FAK serves as prognostic factor in PCa. Previously, VS-6062 (alternatively PF-562,271), another small molecule ATP-competitive FAK inhibitor, was reported to have good antitumor effects on PCa xenografts using PC-3M cells [38]. Interestingly, using the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) mouse model, VS-6062 did not alter the progression to adenocarcinoma, but continued FAK expression was essential for androgen-independent formation of neuroendocrine carcinoma [39]. This fact is consistent with our results, suggesting that innervation-activated FAK may contribute to castration resistant growth of PCa. One phase I clinical trial was conducted using VS-6062 in PCa patients, and the drug was well-tolerated [40]. VS-4718, which we used in this study is also currently in phase I, and VS-6063, another FAKi is in phase 1/1b and II [41]. Thus, FAKi are promising therapeutic targets for CRPC.

In summary, we show that muscarinic receptor activation induces castration resistant growth of PCa cells, this activation leads to phosphorylation of FAK, nuclear translocation of YAP, and that the m1 and m3 stimulated castration resistant growth and YAP activation could be abolished by FAK inhibition. Ultimately, our findings support that innervation induced PCa castration growth can be inhibited by FAK blockade, and that m1, m3, and FAK targeting may represent a new therapeutic strategy for CRPC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, culture conditions and chemicals.

LNCaP, MDAPCa2b, 22Rv1, and PC3 cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination. LNCaP, 22Rv1, and PC3 were cultured in RPMI-1640 (R8758, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (F2442, Sigma-Aldrich), 5% CO2, at 37°C, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (#15140122, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For castrated condition, cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 without phenol-red (#11835030, ThermoFisher Scientific), 5% CSS (#F6765, Sigma-Aldrich). MDAPCa2b were maintained in F-12K (#21127022, ThermoFisher Scientific) Supp.mented with 20% FBS, 25 ng/mL cholera toxin (#C8052, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/mL mouse EGF (#354010, Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 5 μM phosphoethanolamine (#P0503, Sigma-Aldrich), 100 pg/mL hydrocortisone (#H0135, Sigma-Aldrich), 45 nM sodium selenite (#9133, Sigma-Aldrich), and 5 μg/mL human recombinant insulin (#12585–014, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For castrated conditions, 20% of CSS was used instead of FBS. Carbachol was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (#C4382). Enzalutamide (#S1250) and VS-4718 (S7653) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA), Clozapine N-oxide (CNO) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (#C0832), thrombin was purchased from Millipore Sigma (605190), LPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (L7260).

siRNA and transfection.

SiRNAs SMARTpool siGENOME YAP1 was purchased from Dharmacon (#M-012200–00-0005) (Lafayette, CO, USA), siRNA for β-Arrestin 1 was purchased from Qiagen (mix of FlexiTube siRNA #SI02643977 and SI02776921), siRNA for β-Arrestin 2 was purchased from Qiagen (mix of FlexiTube siRNA #SI02776928 and SI03054254), siRNA for m1 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (mix of SASI_Hs01_00076783 and SASI_Hs01_00076782), siRNA for m3 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (mix of SASI_Hs01_00112285 and SASI_Hs01_00112284), and non-targeting control was from Sigma-Aldrich (#SIC-001). All cells were transfected using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Reagent (#13778075, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Antibodies and reagents.

Antibodies against YAP1 (#14074), pYAPS127 (#4911), FAK (#3285), pFAKY397 (#8556), pERK (#4370), ERK (#9102), β-Arrestin1/2 (#4674), β-Actin (#4967) and GAPDH (#2118) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). pYAPY357 (#ab62751) and CHRM3 (ab126168) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). CHRM1 (#nbp1–87466) was purchased from Novus Biologicals, LLC (Centennial, CO, USA).

Cell viability assay.

Cells in 96 well plates were treated as indicated. LNCaP cells and MDAPCa2b cells were seeded on 96 well plates coated with poly-D lysine (#P7280, Sigma-Aldrich). After treatment, culture medium was Supp.mented with 1/100 of the culture volume of Aquabluer reagent (#6015, MultiTarget Pharmaceuticals LLC, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) for 1h to 4h. Absorbances were recorded at 570 nm in a Biotek Synergy Neo microplate reader.

Sphere assay.

Cells were seeded in 96-well ultra-low attachment plate (#CLS3474, Corning, Tewksbury, MA) at 50 cells/well with sphere medium consisted of DMEM/F12 Glutamax (#10565042, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (#13256029, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/mL epithelial growth factor (#PHG0313, Thermo Fisher Scientific), B-27 (#17504044, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and N2 Supp.ment (#17502–048, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Drug was added at the time cells were seeded. After 14 days, the numbers of sphere colonies which are larger than 20 μm were counted under microscope.

DNA constructs.

pLenti-Gαq-DREADD-neo was cloned from pENTR-Gαq-DREADD and pLenti CMV Neo DEST (705–1) by gateway cloning. pENTR-Gαq-DREADD was cloned from pCEFL-Gαq-DREADD [17]. pLenti CMV Neo DEST (705–1) was a gift from Eric Campeau & Paul Kaufman (Addgene plasmid # 17392; http://n2t.net/addgene:17392; RRID:Addgene_17392).

Immunofluorescence.

Cells cultured on coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min, and permeabilized using 0.05% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Fixed cells were blocked with 3% BSA-containing PBS for 30 min, and incubated with YAP antibody (#14074, Cell Signaling Technology) in 3% BSA-PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The reaction was visualized with Alexa-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). SelectFX™ Nuclear Labeling Kit was used for nuclear staining (#S33025, Invitrogen). Images were acquired with an Axio Imager Z1 microscope equipped with ApoTome system controlled by ZEN 2012 software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Single cell protein quantification.

Imaging for at least 3 regions of interest (ROI) for each treatment was acquired using LSM 880 airy scan, and images were processed with ZEN software. Qupath software was used to quantify single cells fluorescence intensity for each marker [42], and average single cell fluorescence intensity for each ROI was calculated.

Quantitative PCR.

RNA was extracted from exponentially growing cultures by the RNeasy Mini Kit following manufacturer’s recommendations (#74104, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). 500 nanogram total RNA was converted to cDNA using SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (#11754250, ThermoFisher Scientific). Q-PCR were performed using SYBR™ Select Master Mix (#4472908, ThermoFisher Scientific). GAPDH was used for normalization. The following primers were used for qPCR. GAPDH fwd 5’- GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT, GAPDH rev 5’- TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG, CHRM1 fwd 5’-TGACCGCTACTTCTCCGTGACT, CHRM1 rev5’-CCAGAGCACAAAGGAAACCA, PSA fwd5’-GCATGGGATGGGGATGAAGTAAG, PSA rev5’-CATCAAATCTGAGGGTTGTCTGGA, CTGF fwd 5’- GTTTGGCCCAGACCCAACTA, CTGF rev 5’- GGCTCTGCTTCTCTAGCCTG, CYR61 fwd 5’- CAGGACTGTGAAGATGCGGT, CYR61 rev 5’- GCCTGTAGAAGGGAAACGCT

Western blotting.

Exponentially growing cells were washed in cold PBS, lysed on ice in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, Supp.mented with Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (#78440, ThermoFisher Scientific)). Cell extracts were collected, sonicated, and centrifuged to remove the cellular debris. Supernatants containing the solubilized proteins were quantified using the detergent compatible DC protein assay kit (#5000111, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. For immunodetection, membranes were blocked for 20 min at room temperature in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST buffer, followed by 2h incubation with the appropriate antibodies, in 3% BSA-T-TBS buffer. Detection was conducted by incubating the membranes with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) at a dilution of 1:20,000 in 5% milk-T-TBS buffer, at room temperature for 40 min, and visualized with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

Genomic data analysis.

Gene mutation and copy number variation analyses where performed using publicly available data generated by The Cancer Gene Atlas consortium, accessed through cBio portal (www.cbioportal.org) [43, 44] and Broad’s Institute Firehose GDAC (gdac.broadinstitute.org/).

Statistical analysis.

All data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The data were analyzed by ANOVA test or t-test or Kaplan–Meier method or Fisher’s exact test. Asterisks denote statistical significance (non-significant or N.S., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001). All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Sample sizes were chosen based on the historical data of the variability and treatment response observed. The variance between the groups that are being statistically compared was similar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Y.G. is supported by the JSPS Overseas Research Fellowships and the Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Fellowship. X.F. is supported by 111 Project of MOE (B14038) China, the National Natural Science Foundation (81402230, 81672677) China. M.G. is supported by FIRC-AIRC fellowship for abroad (Italian Foundation for cancer research). We thank La Jolla Institute Microscopy Core Facility for professional advice and guidance, in particular Zbigniew Mikulski. This work was supported by S10OD021831.

Y.G. initiated the study; Y.G. and J.S.G. designed the study and experiments; Y.G. performed the genomic analyses; Y.G., T.A., H.I., N.A, K.A. performed in vitro experiments, Y.G. and M.G. performed immunofluorescence experiments, Y.G., N.A. and J.S.G. prepared the manuscript, X.F., Z.W., N.A. and J.S.G. provided advice and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

J. Silvio Gutkind is member of the Advisory Board of Oncoceutics and Domain Therapeutics.

Supp. information is available at Oncogene’s website.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019; 69: 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford ED, Higano CS, Shore ND, Hussain M, Petrylak DP. Treating Patients with Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Available Therapies. The Journal of urology 2015; 194: 1537–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauffrey P, Tchitchek N, Barroca V, Bemelmans A, Firlej V, Allory Y et al. Progenitors from the central nervous system drive neurogenesis in cancer. Nature 2019; 569: 672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahalka AH, Arnal-Estape A, Maryanovich M, Nakahara F, Cruz CD, Finley LWS et al. Adrenergic nerves activate an angio-metabolic switch in prostate cancer. Science (New York, NY) 2017; 358: 321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnon C, Hall SJ, Lin J, Xue X, Gerber L, Freedland SJ et al. Autonomic nerve development contributes to prostate cancer progression. Science (New York, NY) 2013; 341: 1236361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee WY, Sun LM, Lin CL, Liang JA, Chang YJ, Sung FC et al. Risk of prostate and bladder cancers in patients with spinal cord injury: a population-based cohort study. Urologic oncology 2014; 32: 51.e51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel N, Ngo K, Hastings J, Ketchum N, Sepahpanah F. Prevalence of prostate cancer in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2011; 3: 633–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grytli HH, Fagerland MW, Fossa SD, Tasken KA. Association between use of beta-blockers and prostate cancer-specific survival: a cohort study of 3561 prostate cancer patients with high-risk or metastatic disease. European urology 2014; 65: 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye JA, Margulis AV, Fortuny J, McQuay LJ, Plana E, Bartsch JL et al. Cancer Incidence after Initiation of Antimuscarinic Medications for Overactive Bladder in the United Kingdom: Evidence for Protopathic Bias. Pharmacotherapy 2017; 37: 673–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N, Yao M, Xu J, Quan Y, Zhang K, Yang R et al. Autocrine Activation of CHRM3 Promotes Prostate Cancer Growth and Castration Resistance via CaM/CaMKK-Mediated Phosphorylation of Akt. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2015; 21: 4676–4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navone NM, Olive M, Ozen M, Davis R, Troncoso P, Tu SM et al. Establishment of two human prostate cancer cell lines derived from a single bone metastasis. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 1997; 3: 2493–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chlenski A, Nakashiro K, Ketels KV, Korovaitseva GI, Oyasu R. Androgen receptor expression in androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate 2001; 47: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutkind JS, Novotny EA, Brann MR, Robbins KC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes as agonist-dependent oncogenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1991; 88: 4703–4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science (New York, NY) 2009; 324: 787–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007; 104: 5163–5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue A, Raimondi F, Kadji FMN, Singh G, Kishi T, Uwamizu A et al. Illuminating G-Protein-Coupling Selectivity of GPCRs. Cell 2019; 177: 1933–1947.e1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng X, Arang N, Rigiracciolo DC, Lee JS, Yeerna H, Wang Z et al. A Platform of Synthetic Lethal Gene Interaction Networks Reveals that the GNAQ Uveal Melanoma Oncogene Controls the Hippo Pathway through FAK. Cancer cell 2019; 35: 457–472.e455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Hayre M, Vazquez-Prado J, Kufareva I, Stawiski EW, Handel TM, Seshagiri S et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 2013; 13: 412–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu V, Yeerna H, Nohata N, Chiou J, Harismendy O, Raimondi F et al. Illuminating the Onco-GPCRome: Novel G protein-coupled receptor-driven oncocrine networks and targets for cancer immunotherapy. The Journal of biological chemistry 2019; 294: 11062–11086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendiratta P, Mostaghel E, Guinney J, Tewari AK, Porrello A, Barry WT et al. Genomic strategy for targeting therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009; 27: 2022–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drake JM, Graham NA, Lee JK, Stoyanova T, Faltermeier CM, Sud S et al. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer reveals intrapatient similarity and interpatient heterogeneity of therapeutic kinase targets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013; 110: E4762–4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora VK, Schenkein E, Murali R, Subudhi SK, Wongvipat J, Balbas MD et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell 2013; 155: 1309–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz S, Wongvipat J, Trigwell CB, Hancox U, Carver BS, Rodrik-Outmezguine V et al. Feedback suppression of PI3Kalpha signaling in PTEN-mutated tumors is relieved by selective inhibition of PI3Kbeta. Cancer cell 2015; 27: 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer cell 2011; 19: 575–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bluemn EG, Coleman IM, Lucas JM, Coleman RT, Hernandez-Lopez S, Tharakan R et al. Androgen Receptor Pathway-Independent Prostate Cancer Is Sustained through FGF Signaling. Cancer cell 2017; 32: 474–489.e476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannan Baig A, Khan NA, Effendi V, Rana Z, Ahmad HR, Abbas F. Differential receptor dependencies: expression and significance of muscarinic M1 receptors in the biology of prostate cancer. Anti-cancer drugs 2017; 28: 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luthin GR, Wang P, Zhou H, Dhanasekaran D, Ruggieri MR. Role of m1 receptor-G protein coupling in cell proliferation in the prostate. Life sciences 1997; 60: 963–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rayford W, Noble MJ, Austenfeld MA, Weigel J, Mebust WK, Shah GV. Muscarinic cholinergic receptors promote growth of human prostate cancer cells. Prostate 1997; 30: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daaka Y G proteins in cancer: the prostate cancer paradigm. Science’s STKE : signal transduction knowledge environment 2004; 2004: re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao X, Qin J, Xie Y, Khan O, Dowd F, Scofield M et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) inhibits androgen-independent activation of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2006; 25: 3719–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu-Chittenden Y, Huang B, Shim JS, Chen Q, Lee SJ, Anders RA et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes & development 2012; 26: 1300–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuser-Abali G, Alptekin A, Lewis M, Garraway IP, Cinar B. YAP1 and AR interactions contribute to the switch from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth in prostate cancer. Nature communications 2015; 6: 8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Yang S, Chen X, Stauffer S, Yu F, Lele SM et al. The hippo pathway effector YAP regulates motility, invasion, and castration-resistant growth of prostate cancer cells. Molecular and cellular biology 2015; 35: 1350–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold JJ, Blinder KJ, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Burdan A, Haynes L et al. Acute severe visual acuity decrease after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin: case reports from randomized clinical trials-TAP and VIP report no. 3. American journal of ophthalmology 2004; 137: 683–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibault F, Corvaisier M, Bailly F, Huet G, Melnyk P, Cotelle P. Non-Photoinduced Biological Properties of Verteporfin. Current medicinal chemistry 2016; 23: 1171–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Ramakrishnan SK, Triner D, Centofanti B, Maitra D, Gyorffy B et al. Tumor-selective proteotoxicity of verteporfin inhibits colon cancer progression independently of YAP1. Science signaling 2015; 8: ra98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konstantinou EK, Notomi S, Kosmidou C, Brodowska K, Al-Moujahed A, Nicolaou F et al. Verteporfin-induced formation of protein cross-linked oligomers and high molecular weight complexes is mediated by light and leads to cell toxicity. Scientific reports 2017; 7: 46581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Roberts WG, Ung E, Whalen P, Cooper B, Hulford C, Autry C et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacology of a selective focal adhesion kinase inhibitor, PF-562,271. Cancer research 2008; 68: 1935–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slack-Davis JK, Hershey ED, Theodorescu D, Frierson HF, Parsons JT. Differential requirement for focal adhesion kinase signaling in cancer progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2009; 8: 2470–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultze A, Fiedler W. Therapeutic potential and limitations of new FAK inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Expert opinion on investigational drugs 2010; 19: 777–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sulzmaier FJ, Jean C, Schlaepfer DD. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nature reviews Cancer 2014; 14: 598–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernandez JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific reports 2017; 7: 16878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Science signaling 2013; 6: pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery 2012; 2: 401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.