Abstract

Context:

Minimally invasive therapeutic modalities have been used to relieve refractory pain of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Objective:

The main objective of the study was to compare the adductor canal block (ACB) with combined ACB and infiltration between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee (I-PACK) in patients suffering knee OA pain.

Patients and Methods:

Fifty-six patients were randomly allocated into two equal groups: Group I received ultrasound-guided ACB with 10 mL of 0.125 bupivacaine plus 40 mg methylprednisolone And Group II received ultrasound-guided ACB with 10 mL of 0.125 bupivacaine plus 40 mg methylprednisolone and I-PACK block using same volume and concentration as ACB.

Results:

Group II showed a statistically significant lower value of visual analog and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities scores at all follow-up intervals compared to Group I.

Conclusion:

Combined ACB and I-PACK block provide more effective analgesia and better functional outcome compared to the ACB alone.

Keywords: Adductor canal block, infiltration between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee, knee osteoarthritis

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disorder that manifested with painful joints, articular stiffness, and decreased physical activity. Knee OA represents about 80% of the total OA burden. Currently, knee OA is one of the main causes of disability in adults and affects their quality of life to large extent. Although the exact etiology of the disease is not clear, many generators of pain in the articular capsule, lateral meniscus, ligaments, bone, tendons, and synovium have been involved.[1]

Both the clinical picture and radiological grading determine the management of knee OA. The commonly used system for radiological grading is Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) system [Table 1]. The grading is according to weight-bearing anteroposterior radiograph of both knees. Increased severity of the disease correlates with higher grades of the scoring system and necessitate surgical intervention.[2]

Table 1.

Kellgren-Lawrence Grading System of osteoarthritis

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No radiographic signs of OA |

| 1 | Doubtful JSN + possible osteophytic lipping |

| 2 | Definite osteophytes + possible JSN |

| 3 | Multiple osteophytes + possible deformity + sclerosis + definite JSN |

| 4 | Marked osteophytes and JSN + severe sclerosis + marked deformity |

JSN=Joint space narrowing, OA=Osteoarthritis

The management of knee OA involves both operative and conservative options. The conservative treatment modalities usually useful for those with KL Grade 1–3, and include both pharmacological and the nonpharmacological modalities.[2]

Pharmacological treatment includes oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nonspecific cyclooxygenase inhibitor, selective Cox-II inhibitors, opiates, nonopioid oral analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, antidepressants, and glucosamine), intra-articular injections (steroids, hyaluronic acid derivatives, and platelet-rich plasma), and topical applications.[2,3,4,5]

Nonpharmacological treatment modalities include physical therapy, lifestyle modification, strengthening exercise, and shoe modification.[6,7,8,9]

However, patients presented with high grade of OA (KL > 3) do not get benefit from conservative modalities and the total knee arthroplasty is the only reliable treatment. But for patients who are unfit for surgery or who refuse to undergo surgery; the other minimally invasive therapeutic options as ultrasound-guided saphenous nerve block may be a good alternative.[10]

The nerves that are contained in the adductor canal include medial femoral cutaneous nerve, the vastus medialis nerve, articular branches from the obturator nerve, and the medial retinacular nerve in addition to the saphenous nerve that innervates the anterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the knee.[11]

Adductor canal block (ACB) is theoretically considered as a pure sensory nerve block. However, as the nerve supplying the vastus medialis muscle passes through the adductor canal, the motor function of the muscle is affected by (ACB).[12]

Furthermore, there is strong clinical evidence that ACB is more effective than femoral nerve block for the preservation of quadriceps muscle strength, providing better ambulatory ability and earlier functional recovery with comparable analgesia, and opioid consumption in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.[13,14]

Thobhani et al. described a novel technique for nerve block which is the ultrasound-guided local anesthetic infiltration between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee (I-PACK). This block targeted the terminal branches of the sciatic nerve only and can alleviate pain from the posterolateral aspect of the knee joint without foot drop.[15]

However, the clinical trials comparing the analgesic effectiveness and physical rehabilitation, with the addition of an I-PACK block to ACB are limited.

This study hypothesized that combined ACB and I-PACK block are more effective than ACB alone for alleviating pain of knee OA and improving quality of life. This study was aiming to compare ACB with combined ACB and I-PACK in patients suffering knee OA pain.

Improvement in pain intensity as evaluated by visual analog score (VAS) represents the primary outcome, while functional outcome of the patients and reduction of disease progression as evaluated by Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) questionnaire represents the secondary outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

After getting clearance from our medical institution (R.19.02.416), this prospective randomized comparative study was carried out on 56 patients referred to our pain clinic. Written informed consent, including full description of the technique, drugs, and side effects, was obtained from all the participants.

Inclusion criteria

Patients over the age of 45 years, of ASA Physical Status I–III, and of either sex

Patients who were competent to understand the study protocol

Radiographic evidence of OA of knee of the second degree or more

Chronic pain prior to study entry for at least 6 months

Pain did not respond to conservative therapies during the last 6 months.

Exclusion criteria

Patient refusal

Bleeding or coagulation disorders

Local skin infection or any other medical problem in the affected limb

Psychiatric problems lead to difficult communication with the patient

Previous chronic opioid use

Contraindications to steroid injection as diabetes or hypertension.

Randomization

Eligible 56 patients will be randomly allocated into two equal groups of 28 patients each according to computer-generated randomization program. Each patient was assigned as I or II according to his or her group, followed by a number from 1 to 56 according to his or her order.

Group I (n = 28) received ultrasound-guided ACB with 10 mL of 0.125 bupivacaine plus 40 mg methylprednisolone

Group II (n = 28) received ultrasound-guided ACB with 10 mL of 0.125 bupivacaine plus 40 mg methylprednisolone and I-PACK block using same volume and concentration as ACB.

Technique of ultrasound-guided adductor canal block

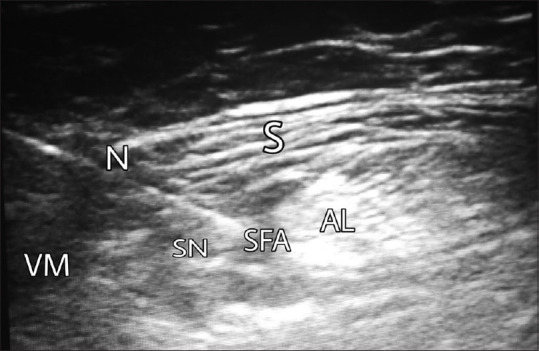

Before the procedure, standard monitoring was applied, including noninvasive arterial blood pressure, electrocardiography, and pulse oximetry. An intravenous cannula (20 G) was inserted in a peripheral vein for crystalloid infusion. Using a portable ultrasound machine, with linear transducer (7–12 MHz), the block was performed subsartorial at the exit of the adductors canal, using the in-plane technique. Under aseptic techniques, the patient was placed supine, with the knee slightly flexed and external rotation of the hip. First scanning of the medial aspect of the thigh was done to locate the saphenous nerve, which lies near the superficial femoral femoral vessels.[16] It gives out articular branches on coming out of the sartorial canal via infrapatellar branch. The adductor canal contains also nerve to vastus medialis which gives articular branches to the knee via the medial retinacular nerve. One 10-cc syringe was filled with 10 mL of bupivacaine 0.125% plus 40 mg methylprednisolone and attached to a 22-gauge spinal needle. The needle passed in-plane with short-axis view under vastoadductor membrane (connects vastus medialis laterally and adductor muscles medially) and sartorius muscle reach the saphenous nerve and nerve to vastus medialis after negative aspiration for blood, the content was injected. The patient was observed for half an hour and then made to walk [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Adductor canal block. N = Needle, S = Sartorius muscle, VM = Vastus medialis muscle, AL = Adductor longus muscle, SFA = Superficial femoral artery, SN = Saphenous nerve

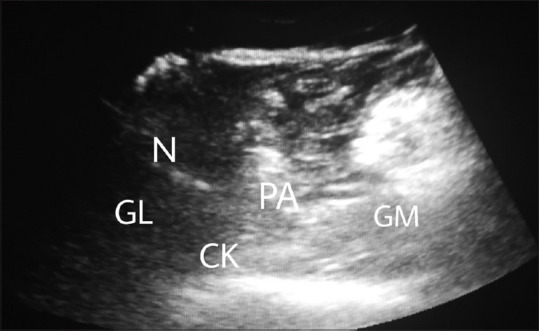

Technique of ultrasound-guided infiltration between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee block

With the patient in the lateral position, knee slightly flexed, hip externally rotates, a curvilinear (2–6MHz) was placed over the popliteal fossa at the level of femoral condyles. Color Doppler was used to delineate the popliteal artery in a short-axis view. After strict sterilization and draping, a 22-gauge spinal needle was passed using in-plane technique from lateral to medial through the lateral head of gastrocnemius muscle with needle tip destination between popliteal artery and posterior capsule of the knee.[11] The same volume and concentration of injectate used in ACB was injected under real-time visualization [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Infiltration between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee block. N = Needle, PA = Popliteal artery, CK = Posterior capsule of the knee, GL = Gastrocnemius lateral head, GM = Gastrocnemius medial head

Collected data

Demographic data including grade of OA

VAS:[17] was reported at preprocedure, and 2, 4, 8, and 12 months after the procedures

-

Quality of life was evaluated using the WOMAC index of OA.[18] A series of 24 questions which evaluated pain, stiffness, and physical function were used:

- Pain: During walking, using stairs, in bed, sitting or lying, and standing upright

- Stiffness: Evaluated at first waking and then later in the day

- Physical function: Rising from or lying in bed, getting in/out of bath, toilet, or car, walking, rising from sitting, bending, standing, putting on/taking off socks, climbing stairs.

The total score is between 0 (no disability) and 96 (lack of autonomy). Patients answered this questionnaire before the procedure and at each follow-up interval.

Sample size calculation

The base of sample size calculation for this study was detection of a two-point difference after the procedure for the outcome pain intensity, as assessed by VAS (estimated standard deviation of 2.5).[10] For achieving a two-sided 5% significance level and a power of 80%, a sample size of 26 patients was needed. A dropout of 10% of cases was expected, so 28 patients per group were required.

Statistical analysis

For the current study, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM Crop. Released 2013.IBM Statistics for Windows, version 22. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Crop.,) was used for the statistical analysis. Regarding the quantitative data, normality was first tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and then analyzed with the Student's t-test. The nonparametric and ordinal data were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U-test. For binomial data, Fisher's exact test was used. All P values presented here were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

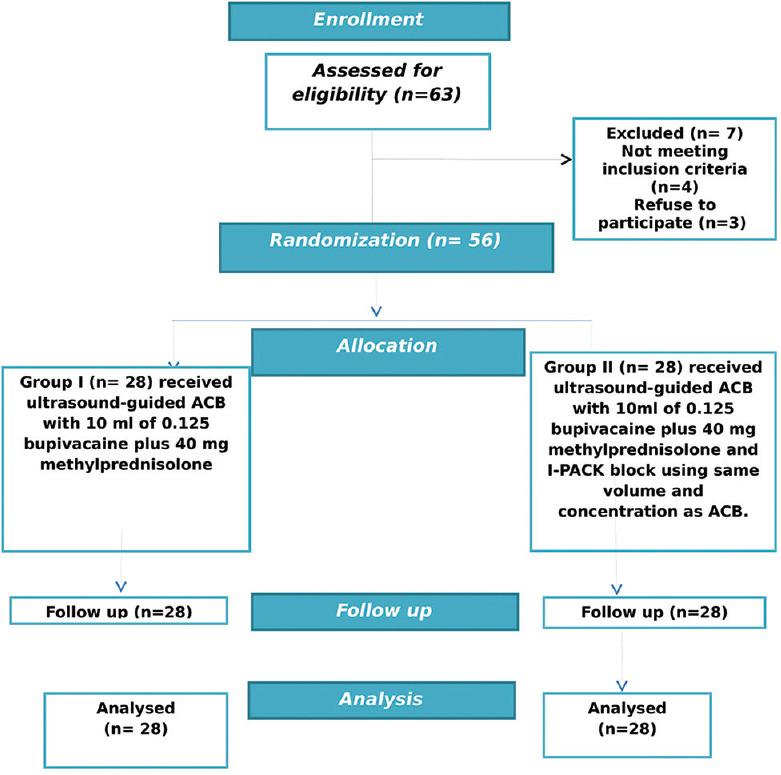

A total of 56 patients were enrolled in this study [Figure 3]. The two groups of participants did not show statistically significant difference regarding patient characteristics [Table 2].

Figure 3.

Consort flow chart

Table 2.

Demographic data of the studied groups. Data are presented as mean±SD/Numbers (%)

| Group | Group (I) n=28 | Group (II) n=28 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 54±13 | 52±15 | 0.59 |

| Gender (male/female) | 19/9 (18%:32%) | 20/8 (14%:86%) | 0.77 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5±3 | 29.1±2.7 | 0.46 |

| Site | RT: 16 (57%) | RT: 14 (50%) | 0.59 |

| LT: 12 (43%) | LT: 14 (50%) | ||

| Osteoarthritis grade | II: 46%(13) | II: 57%(16) | 0.59 |

| III: 54%(15) | III: 43%(12) | ||

| ASA classification | I: 96%(27) | I: 82%(23) | 0.19 |

| II: 4%(1) | II: 18% (5) |

Group (I): Received ultrasound-guided ACB (adductor canal block), Group (II): Received ultrasound-guided ACB and I-PACK, RT: Right, LT: Left, ASA: American society of anesthesiologist, BMI: Body mass index

Regarding the VAS and WOMAC index, Group II showed statistically significant lower values at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks compared to Group I [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Basal and follow up values of the VAS of the studied groups. Data are expressed as median (range)

| Group (I) n=28 | Group (II) n=28 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal (before block) | 7 (7-8) | 8 (7-8) | 0.59 |

| 2 weeks | 5 (3-7)† | 4 (3-8)† | 0.001* |

| 4 weeks | 5 (3-7)† | 4 (3-8)† | 0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 5 (3-7) | 4 (3-8)† | 0.001* |

| 12 weeks | 6 (3-9) | 4 (3-9) | 0.001* |

Group (I): Received ultrasound-guided ACB (adductor canal block), Group (II): Received ultrasound-guided ACB and I-PACK, VAS: Visual analogue score. *P≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant between the two groups. †P≤0.05 was considered as highly significant in comparison with basal value

Table 4.

Basal and follow up values of the WOMAC index of the studied groups. Data are expressed as median (range)

| Group (I) n=28 | Group (II) n=28 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal (before block) | 65 (62.3-71) | 70.5 (65.5-72) | 0.1 |

| 2 weeks | 58 (56.3-46.8)† | 54.5 (53.3-39.8)† | 0.001* |

| 4 weeks | 55.5 (53.3-61.5)† | 52 (50-54.8)† | 0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 55.5 (53.3-61.5)† | 50 (48-53.5)† | <0.0001* |

| 12 weeks | 59.5 (54.3-63.8)† | 56.5( 51.3-56.8)† | 0.001* |

Group (I): Received ultrasound-guided ACB (adductor canal block). Group (II): Received ultrasound-guided ACB and I-PACK. WOMAC: Western Ontario and MC Master Universities. *P≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant between the two groups. †P≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant in comparison with basal value

A statistically significant decrease in comparison with basal values of VAS and WOMAC index was noted in both groups at all follow-up intervals [Tables 3 and 4].

No complications noted in both groups.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the current study was to compare the effect of I-PACK block supplementing ACB versus ACB only in patients suffering knee OA pain. In accordance with our hypothesis, the combined ACB and I-PACK are more effective in alleviating pain and improving physical function in those patients compared to the ACB only.

OA is a growing health problem and considered as a leading cause of disability and limitation of work.[19]

The nerve supply of the knee is derived from two main sources: (1) the femoral nerve, which supplies the anterior and to a lesser extent, the medial aspects and (2) the sciatic nerve, which supplies the posterior aspect.[15]

It has been reported in the literature that the continuous femoral nerve catheter can provide marked postoperative analgesia, but on the other hand, it leads to a marked weakness of quadriceps that interfere with early physical activity.[20]

The ACB carries the advantage of providing comparable degree of analgesia as that of single injection of femoral nerve catheter block with preservation of quadriceps muscle strength with early and better physical rehabilitation.[21]

However, the posterior aspect of the knee still out of the scope of ACB, and the patient frequently encounter postoperative pain and needs analgesic medication.[22]

The combined sciatic nerve block and femoral nerve block could provide acceptable analgesia and decrease opioid consumption.[23] However, the sciatic nerve block may be complicated by a sensory and motor deficit below level of the knee with increased risk of foot drop.[24]

The ultrasound-guided I-PACK is a novel technique for nerve block act only on terminal branches of the sciatic nerve, so it can provide analgesia for posterior aspect of the knee with a very low possibility of foot drop.[25]

Amer documented that combined ACB and I-PACK blocks are more effective than combined ACB and intraarticular infiltration for postoperative pain following anterior cruciate ligament surgery.[11]

Thobhani et al. compared patients underwent total knee arthroplasty and received continuous perineural infusion, either femoral nerve catheter block or ACB in combination with I-PACK block in both groups. The authors noted that patients in the ACB with I-PACK group had comparable pain scores but much better functional outcomes, including physical activity and earlier hospital discharge. They also recommended further studies comparing ACB alone and combined with I-PACK block.[15]

In accordance with previous studies, the current study reported a statistically significant lower pain score and WOMAC questionnaire in group of patients received combined ACB and I-PACK block compared to those received ACB alone.

The short duration of follow-up may be a limitation of this study.

CONCLUSION

The technique of combined ACB and I-PACK block provides more effective analgesia and better functional outcome compared to the ACB alone in patients suffering knee OA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee J, Song J, Hootman JM, Semanik PA, Chang RW, Sharma L, et al. Obesity and other modifiable factors for physical inactivity measured by accelerometer in adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:53–61. doi: 10.1002/acr.21754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaishya R, Pariyo GB, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Non-operative management of osteoarthritis of the knee joint. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Ryan SI. Comparison of an antiinflammatory dose of ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen, and acetaminophen in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:87–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107113250203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes R, Carr A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of glucosamine sulphate as an analgesic in osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:279–84. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Weight loss: The treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page CJ, Hinman RS, Bennell KL. Short term beneficial effects of exercise on pain and function. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebnezar J, Nagarathna R, Yogitha B, Nagendra HR. Effects of an integrated approach of hatha yoga therapy on functional disability, pain, and flexibility in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: A randomized controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:463–72. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Yang L, Li H, Lei Z, Yang X, Liu C, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration training with quadriceps strengthening exercise on functioning and gait parameters in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: A randomised controlled preliminary study. Physiotherapy. 2016;102:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akkaya T, Ersan O, Ozkan D, Sahiner Y, Akin M, Gümüş H. Saphenous nerve block is an effective regional technique for post-menisectomy pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:855–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amer N. Combined adductor canal and i-PAK blocks is better than combined adductor canal and periarticular injection blocks for painless ACL reconstruction surgery. J Anesth Crit Open Access. 2018;10:154–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memtsoudis SG, Yoo D, Stundner O, Danninger T, Ma Y, Poultsides L, et al. Subsartorial adductor canal vs. femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2015;39:673–80. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao F, Ma J, Sun W, Guo W, Li Z, Wang W. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:356–68. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Ma GG. Analgesic efficacy and quadriceps strength of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2614–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thobhani S, Scalercio L, Elliott CE, Nossaman BD, Thomas LC, Yuratich D, et al. Novel regional techniques for total knee arthroplasty promote reduced hospital length of stay: An analysis of 106 patients. Ochsner J. 2017;17:233–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai PB, Karnwal A, Kakazu C, Tokhner V, Julka IS. Efficacy of an ultrasound-guided subsartorial approach to saphenous nerve block: A case series. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:683–8. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), mcGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form mcGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–52. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stucki G, Sangha O, Stucki S, Michel BA, Tyndall A, Dick W, et al. Comparison of the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster universities) osteoarthritis index and a self-report format of the self-administered lequesne-algofunctional index in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6:79–86. doi: 10.1053/joca.1997.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grevstad U, Mathiesen O, Valentiner LS, Jaeger P, Hilsted KL, Dahl JB. Effect of adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block on quadriceps strength, mobilization, and pain after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, blinded study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:3–10. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson ME, Bland KS, Thomas LC, Elliott CE, Soberon JR, Jr, Nossaman BD, et al. The adductor canal block provides effective analgesia similar to a femoral nerve block in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty – A retrospective study. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadeau JT, Goytizolo EA, Padgett DE, Liu SS, Mayman DJ, Ranawat AS, et al. Analgesia after total knee replacement: Local infiltration versus epidural combined with a femoral nerve blockade: A prospective, randomised pragmatic trial. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:629–35. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B5.30406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham Dang C, Gautheron E, Guilley J, Fernandez M, Waast D, Volteau C, et al. The value of adding sciatic block to continuous femoral block for analgesia after total knee replacement. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baratta JL, Gandhi K, Viscusi ER. Perioperative pain management for total knee arthroplasty. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2014;23:22–36. doi: 10.3113/jsoa.2014.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vlessides M. New regional technique controls post-TKA pain. Anesthesiol News. 2012;38:17. [Google Scholar]