Abstract

In the field of public health, treatment of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infection is a great challenge. Herein, we provide a solution to this problem with the use of graphene oxide-silver (GO-Ag) nanocomposites as antibacterial agent. Following established protocols, silver nanoparticles were grown on graphene oxide sheets. Then, a series of in vitro studies were conducted to validate the antibacterial efficiency of the GO-Ag nanocomposites against clinical MDR Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains. GO-Ag nanocomposites showed the highest antibacterial efficiency among tested antimicrobials (graphene oxide, silver nanoparticles, GO-Ag), and synergetic antibacterial effect was observed in GO-Ag nanocomposites treated group. Treatment with 14.0 µg ml−1 GO-Ag could greatly inhibit bacteria growth; remaining bacteria viabilities were 4.4% and 4.1% for MDR-1 and MDR-2 E. coli bacteria, respectively. In addition, with assistance of photothermal effect, effective sterilization could be achieved using GO-Ag nanocomposites as low as 7.0 µg ml−1. Fluorescence imaging and morphology characterization uncovered that bacteria integrity was disrupted after GO-Ag nanocomposites treatment. Cytotoxicity results of GO-Ag using human-derived cell lines (HEK 293T, Hep G2) suggested more than 80% viability remained at 7.0 µg ml−1. All the results proved that GO-Ag nanocomposites are efficient antibacterial agent against multidrug-resistant E. coli.

Keywords: in vitro, MDR E. coli, graphene oxide-silver, photothermal treatment

1. Introduction

Antibiotics have been widely used for over 70 years in different fields such as medicines, agriculture and environment [1]. However, bacteria have developed resistance to antibiotics through acquired resistance genes or intrinsic antibiotic resistance capability [2], which leads to the wide existence of resistant bacteria, including multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria and pandrug-resistant bacteria [3]. In diagnosis practice, antibiotic resistance is a non-negligible concern for clinical physicians to treat infections such as post-operative infections, ear, nose and throat infections, and urinary tract infections. Antibiotic resistance makes antibiotic selection a great challenge as more and more MDR bacteria were found in patients [4–6]. Among all the infections encountered in hospital, urinary tract infections are one of the most common infections, in which case E. coli is found to be the major cause [7]. Moreover, spreading of certain type of antibiotic-resistant E. coli may become potential cause for epidemic disease [8]. Several scientific reports have indicated that antibiotic-resistant E. coli bacteria are found in soil, water, foods and animals [9–15]. Due to the wide spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and less efficiency of conventional antibiotics, alternatives are needed to deal with antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Nanotechnology offers a new way to overcome healthcare challenges brought by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as the nanoscale antimicrobial agents have huge surface to volume ratio, and the size is comparable to the pathogenic microbes, allowing it to penetrate into or contact with pathogenic microbes in an efficient way [16]. Most of the effective antimicrobials are metallic-based nanomaterials such as ZnO, TiO2, silver and gold nanoparticles [17–20]. Among different nanomaterials, silver-based nanomaterials are the most popular antibacterial agent [21,22]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are effective against Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, as well as MDR bacteria, while the antibacterial mechanism is still not clear though several hypotheses were propounded [23–26]. Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms nanomaterial, has a unique set of physical, chemical and electronic properties [27–29], which enable it as novel agent for biomedical applications. Graphene-based nanomaterials are used as novel antimicrobial agents against broad-spectrum microbes via physical destruction of cell membrane and chemical damage brought by reactive oxygen species [30,31]. However, there are debates on antibacterial activity of graphene and graphene oxide (GO) as several papers claimed little antibacterial activity of graphene oxide [32,33]. Furthermore, graphene can serve as carrier for antibiotics delivery [34], and photothermal sensitizers in combination with near-infrared laser light for powerful photothermal killing of bacteria [35,36].

GO-Ag nanocomposites are widely reported to be efficient antimicrobial agents to different kinds of microbes, including standard bacteria, fungus and resistant bacteria [37–42]. It shows better antibacterial efficiency in comparison with silver nanoparticles, because GO sheet provides anchor platform to make AgNPs well dispersed and large contact surface between bacteria and AgNPs [40,43]. However, most of the studied bacteria were model bacteria instead of clinically isolated bacteria, especially MDR bacteria encountered in clinical practice. Furthermore, photothermal property of GO can be used for combined therapy to improve antibacterial efficiency, as well as to reduce risk of potential anti-nanomaterial resistance as silver-resistant bacteria were reported [44,45].

In order to find a way to address resistance problem of MDR bacteria in clinical practice, photothermal-assistant anti-MDR E. coli bacteria study is conducted using synthesized GO-Ag nanocomposites. To achieve reliable antibacterial efficiency, we break the study into four steps. First step is to verify the existence of synergistic effect of GO-Ag nanocomposite in comparison with AgNPs. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of AgNPs, GO-Ag and some antibiotics is used to evaluate the antibacterial efficiency according to standard protocol. Second step is to find possible cause for improved antibacterial efficiency of GO-Ag, and to clarify the debates on GO antibacterial activity. Antibacterial efficiency of GO, AgNPs, GO-Ag and a mixture of GO and AgNPs are studied simultaneously using a colorimetric assay with dye 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), namely MTT assay. In the third step, in vitro photothermal-assistant treatment of MDR bacteria is conducted with energy from near-infrared laser light to kill MDR bacteria in more efficient way. Finally, characterization of GO-Ag-treated bacteria is performed using fluorescence microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to indicate resulting damage after treatment. Moreover, cytotoxicity of GO-Ag was tested using human-derived cell lines as it is a serious concern for any further applications.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

AgNO3, sodium citrate, expandable graphite flakes, sodium chloride, H2SO4, KMnO4, 30% H2O2, HCl and NaOH are chemicals used for nanomaterials synthesis. Antibiotics including ampicillin, tetracyline, streptomycin and chloramphenicol are used for MIC testing. Tryptone, yeast extract, agar, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and MTT are used for bacteria culture and cell viability assay. All the reagents are purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Bacteria strain and cell lines

Two MDR E. coli strains are isolated from urine samples in clinical laboratory. These two bacteria are named MDR-1 and MDR-2, respectively, and their antibiotic susceptibility was tested in clinical laboratory. MDR-1 is resistant to penicillin (ampicillin, AMP), tetracyline (tetracyline, TET), quinolone (nalidixic acid, NAL) and aminoglycoside (streptomycin, STR). MDR-2 is resistant to penicillin (ampicillin, AMP), tetracyline (tetracyline, TET), quinolone (nalidixic acid, NAL), aminoglycosides (spectinomycin, SPE; gentamicin, GEN) and chloramphenicol (chloramphenicol, CHL).

Human embryonic kidney 293T cell (HEK 293T, ATCC CRL-1573) and human liver hepatocellular cell (Hep G2, ATCC HB-8065) were gifts from Jiangnan University.

2.3. Preparation and characterization of GO, AgNPs and GO-Ag nanocomposites

AgNPs were synthesized according to previously reported method [46]. First, 18 mg silver nitrate was added into 100 ml distilled (DI) water, and the solution was heated in oil bath until boiling. Afterwards, 20 mg sodium citrate in 2 ml DI water were added to boiled silver nitrate solution slowly. Then solution was kept boiling for 1 h. Synthesized AgNPs solution cooled to room temperature, and some sample were taken out for characterization. Graphene oxide sheets were prepared using a modified Hummer method [47,48]. Silver nanoparticles were deposited on GO sheets via reducing of silver nitrate using sodium citrate in GO aqueous solution. Briefly, 6 mg GO and 18 mg AgNO3 were dissolved in 100 ml DI water under stirring in oil bath, 1% sodium citrate aqueous solution (2 ml) was added slowly in boiling solution. The solution was kept boiling for 1 h to produce GO-Ag nanocomposites. Then, the product was filtered and washed with DI water three times.

The content of silver in AgNPs and GO-Ag nanocomposites was measured using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). In detail, three samples were taken out and diluted at different level, then nitric acid was added to dissolve samples. Well dissolved samples were centrifuged to remove precipitate, supernatant samples were used for quantitative ICP-AES analysis. Concentrations of GO in GO-Ag nanocomposites were measured using spectrometer and weighing method after lyophilization. Extinction coefficient of GO was 21.2 mg ml−1 cm−1 at wavelength of 900 nm.

Absorption spectrum of GO (3 µg ml−1), AgNP (4 µg ml−1) and GO-Ag (7 µg ml−1) dispersed in water were scanned using spectrophotometer. GO and GO-Ag were also characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM; Tecnai G20 F20, FEI) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential (Zetasizer Nano, ZS90, Malvern). GO sheets were also characterized and analysed by atomic force microscope (AFM; Veeco) and software NanoScope 6.14R1. AgNP size distribution on GO-Ag nanocomposites was measured and analysed using software ImageJ 1.52d and JMP 14.2.0.

2.4. MIC of antimicrobial agents against MDR E. coli

According to a reported protocol [49], agar dilution method was used for MIC determination. At first, LB agar contained different concentrations of antimicrobials were prepared, and 2 µl bacteria suspension (10 000 CFU) were dropped on the surface of LB agar. LB agar plate was put upward for 0.5 h to allow inoculum fully absorbed into the agar. Afterwards, plates were incubated for 16 h in 37°C incubator. Two MDR bacteria strains susceptibility testing was done using a series of antimicrobials. They were GO-Ag, AgNPs, AMP, TET, STR and CHL, and corresponding concentrations were 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 and 512 µg ml−1. Tests repeated at least three times.

2.5. In vitro antibacterial assessment of antibacterial agents

Single colony on agar plate was transferred to fresh LB broth, and then cultured for 12 to 16 h in 37°C shaker at speed of 250 r.p.m. After centrifugation, bacteria pellet was resuspended in 4.5 ml fresh LB broth to a final concentration of 107–108 CFU ml−1. Then, 0.5 ml nanomaterials were added into broth and mixed well. Afterwards, broth was incubated with nanomaterials at 37°C for 3 h before viability assessment. Tested antibacterial agents included GO, AgNPs, GO-Ag, GO + AgNPs (mixture of GO and AgNPs). Three levels of GO concentrations were 1.5, 3 and 6 µg ml−1; silver concentrations were 2, 4 and 8 µg ml−1; corresponding nanocomposites or mixture concentrations were 3.5, 7 and 14 µg ml−1. Three samples were tested for each treated group.

Similar to reported protocol used to evaluate interaction between biomaterial and cell [50], MTT assay method was used to evaluate bacterial viability after incubation with antimicrobial agents. At first, 0.1 ml bacteria culture was transferred into 96-well plate, and mixed well with 20 µl 5 mg ml−1 MTT solution for 16 h in 37°C incubator. After centrifugation (5 min, 2000 r.p.m.), supernatant was removed and replaced with 120 µl DMSO in each well. Afterwards, microplate was shaken for 10 min to dissolve precipitants. At last, OD570 were read by microplate reader (Bio-Rad). Three parallel samples were tested with three replicates for each sample.

2.6. In vitro photothermal treatment of MDR-2 E. coli

Overnight cultured MDR-2 bacteria were collected and resuspended in fresh LB broth to a final concentration of 107–108 CFU ml−1. Then, 10% volume of nanocomposites (GO, GO-Ag) or water (control) was added into LB broth, final concentration of GO and GO-Ag were 3 and 7 µg ml−1. The broth was shaken at 37°C for 1 h before laser irradiation. Then, 1 ml bacteria culture was transferred into one well of 24-well plate, and 808 nm laser light was used to irradiate the broth. Irradiation lasted for 7 min at different energy density, including 0, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 W cm−2. Temperature during laser irradiation was recorded by thermal camera. After irradiation, the mixture was cultured for 6 h before bacteria viability assessment. Viability assessment was conducted by spread plate method and MTT assay.

2.7. Fluorescence imaging of treated MDR-2 E. coli

Four groups of bacteria were prepared to observe their effects on survival status of bacteria, which were brought by photothermal irradiation (1.5 W cm−2, 7 min) and GO-Ag treatment (7 µg ml−1). After above treatment, MDR-2 E. coli were cultured for 6 h. Next, collected bacteria cells were washed and stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and propidium iodide (PI). According to reported protocol [51], bacteria were washed in 10 mM MgSO4 at pH 6.5 after centrifugation. And then, bacteria were stained with PI (5 µg ml−1) and DAPI (5 µg ml−1) for 30 min in dark. After drying in air, the samples were observed under confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II).

2.8. Morphology characterization of GO-Ag-treated MDR-2 E. coli

MDR-2 E. coli with or without GO-Ag (14 µg ml−1) was cultured in LB broth for 3 h. After that, the bacteria were collected and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Next, the bacteria were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution, and then the cells were dehydrated by sequential treatment with 50%, 70%, 90% and 100% ethanol for 15 min. Finally, bacteria were transferred to a silicon wafer for gold sputter coating, and then imaged under SEM (Quanta 200FEG, FEI).

2.9. Mammalian cytotoxicity of GO-Ag nanocomposite

HEK 293T and HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. About 100 000 cells/well were seeded into 96-well microplates in the presence of 150 µl medium with GO-Ag nanocomposites, then cells were incubated for 24 h in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Five replicates (wells) per concentration were conducted at different final concentrations of GO-Ag (0, 3.5, 7, 14, 20, 50 µg ml−1). After 24 h incubation, 15 µl MTT solution (5 mg ml−1) was added into microplates and well mixed before 4 h incubation. The microplates were then centrifuged at 2000 r.p.m. for 5 min. Supernatant was discarded and replaced with 150 µl DMSO to dissolve purple crystals of formazan. At last, microplates were well mixed, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm by microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial agents' characterization

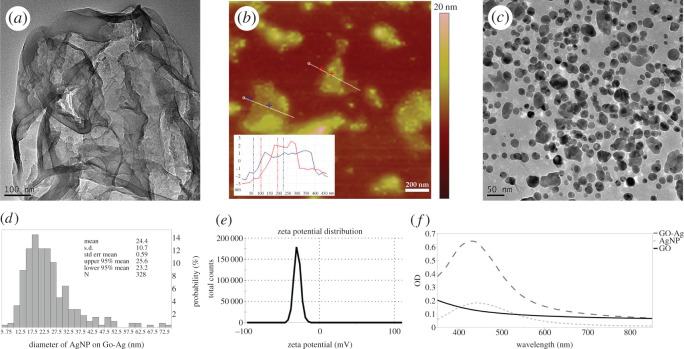

In this study, GO, AgNP and GO-Ag were synthesized to investigate their antibacterial efficiency. Following reported protocol, GO sheets were prepared at first. As figure 1a shows, thin GO sheet was synthesized successfully. AFM analysis (figure 1b) revealed both single layer and multilayer sheets existed in synthesized GO. AgNPs were grown on GO sheets by in situ reducing silver nitrate solution on GO sheet. The synthesized GO-Ag nanocomposite was confirmed by observed absorption band around 440 nm (figure 1f) and TEM image (figure 1c). Figure 1d shows AgNP size distribution on GO-Ag; more than 90% AgNPs were in the range of 10–40 nm, and average diameter was 24.38 ± 10.74 nm. After silver nanoparticles decorated on GO sheets, zeta potential increased from −36.1 ± 6.98 mV (GO, electronic supplementary material, figure S1) to −28.8 ± 4.51 mV (GO-Ag, figure 1e). Size distribution of GO-Ag was characterized by DLS method; results were 147.4 ± 85.16 nm (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Figure 1.

Characterization of synthesized nanomaterials. (a) TEM image of GO. (b) AFM image of GO. (c) TEM image of GO-Ag nanocomposites. (d) Size distribution of AgNP on GO-Ag. (e) Zeta potential distribution of GO-Ag. (f) Absorption spectrum of GO, AgNP and GO-Ag dispersed in water.

In order to quantify silver content in AgNP and GO-Ag, both materials were decomposed with nitric acid. Three levels of diluted samples were tested using ICP-AES, and dose was averaged results of three level samples. GO content in GO-Ag was measured using spectrometer at 900 nm. Results are shown in table 1; synthesized AgNP dose was 976 µg ml−1, and averaged silver and GO content in GO-Ag nanocomposites was 43% and 57%, respectively.

Table 1.

Component content of GO-Ag and AgNP. Ag content was quantified using ICP-AES, and GO content was measured using spectrometer at 900 nm (extinction coefficient was 21.2 mg ml−1 cm−1). Dose = dilution factor × measured content.

| sample | dilution factor | AgNP | GO-Ag |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag content (μg ml−1) | Ag content (μg ml−1) | GO content (μg ml−1) | ||

| no. 1 | 2 | 462 | 188 | 267 |

| no. 2 | 5 | 193 | 91 | 108 |

| no. 3 | 10 | 104 | 38 | 53 |

| mean dose (μg ml−1) | 976 | 404 | 535 | |

| content (%) | 100 | 43 | 57 | |

3.2. MIC testing using agar dilution method

MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that inhibits visible growth of microorganisms after overnight incubation. AgNP, GO-Ag and antibiotics (penicillin, tetracyline and aminoglycoside) were tested in two clinical MDR bacteria strains. Results (table 2) showed that both bacteria were resistant to AMP, TET, STR or CHL. MIC dose for all typical antibiotics are greater than or equal to 256 µg ml−1, while MIC dose of nanomaterial-based antibacterial agents are much lower. As shown in table 2, MIC dose of GO-Ag and AgNPs were 4 and 32 µg ml−1, respectively. Compared with AgNP, a widely used antimicrobial agent, GO-Ag showed higher antibacterial efficiency against two clinical MDR E. coli strains; 4 µg ml−1 GO-Ag could completely inhibit growth of MDR-1 and MDR-2 bacteria on LB agar. No visual colony was observed on LB agar with 10 000 CFU bacteria cultured on agar media overnight.

Table 2.

MICs of MDR E. coli.

| GO-Ag (µg ml−1) | AgNP (µg ml−1) | AMP (µg ml−1) | STR/CHL (µg ml−1) | TET (µg ml−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDR-1a | 4 | 32 | >512 | >512 (STR) | 256 |

| MDR-2a | 4 | 32 | >512 | >512 (CHL) | 512 |

aMDR-1 and MDR-2 were two isolates of MDR E. coli from clinical samples. MDR-1 was resistant to ampicillin (AMP), tetracyline (TET), nalidixic acid (NAL) and streptomycin (STR), MDR-2 was resistant to ampicillin (AMP), tetracyline (TET), nalidixic acid (NAL) and chloramphenicol (CHL), spectinomycin (SPE) and gentamicin (GEN).

3.3. Synergetic antibacterial effect verification of GO-Ag

In order to find why GO-Ag nanocomposites showed higher antibacterial efficiency than AgNP, we decomposed GO-Ag nanocomposites and measured the ratio of GO and Ag by ICP-AES and spectrometer. Results (table 1) showed content of GO and AgNP were 57% and 43% respectively in GO-Ag nanocomposite. Afterwards, three levels of AgNP (2, 4, 8 µg ml−1), GO (1.5, 3, 6 µg ml−1) and GO-Ag (3.5, 7, 14 µg ml−1) nanocomposites were tested for antibacterial efficiency comparison. Besides, GO + AgNP mixture was used as control group to verify existence of synergetic effect of GO-Ag nanocomposites.

Antibacterial efficiency testing was studied in LB broth, and 3 h incubation time was selected as bacteria were in the middle of log phase. Thus, it is easier for us to discriminate minor difference between treated and control groups.

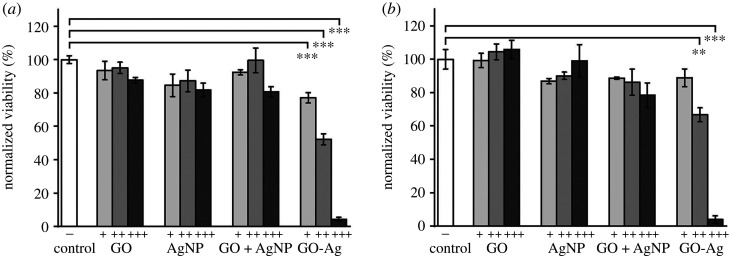

Quantification results are shown in figure 2a,b. GO-Ag showed the highest antibacterial efficiency among tested nanomaterials. As concentration increased, remaining viabilities of two MDR E. coli strains decreased obviously in GO-Ag-treated group. Correspondingly, remaining viabilities of MDR-1 and MDR-2 were 77.1%, 52.2%, 4.4% and 88.9%, 66.8%, 4.1%, respectively. On the other hand, there was no obvious viability decrease trend with increased concentrations of GO or AgNP. In AgNP-treated group, the remained viabilities of MDR-1 and MDR-2 were in the range of 81.8%–99.1%. In GO-treated group, the remained viability of MDR-1 and MDR-2 were in the ranges of 87.7% to 95.1% and 99.3% to 105.9%. Compared with GO-Ag nanocomposite, GO + AgNP mixture did not show observable viability decrease trend with increasing mixture concentration. The above results demonstrated that high antibacterial efficiency of GO-Ag arose from synergetic effect of GO and AgNPs after they combined as composite. Moreover, two MDR E. coli bacteria showed similar response to different nanomaterial. A minor difference was that MDR-2 bacteria were less susceptible to GO-Ag than MDR-1 bacteria at low concentration. When GO-Ag concentration was 3 µg ml−1, no significant inhibition was observed in MDR-2 E. coli group.

Figure 2.

MDR E. coli viability assessment by MTT assay. (a) MDR-1 E. coli viability and (b) MDR-2 E. coli viability after treatment with GO, AgNP, GO-Ag, mixture of GO and AgNP (GO + AgNP) at different final concentrations in LB broth. +, ++, +++ represent different concentrations for different groups. GO (+, 1.5 µg ml−1; ++, 3 µg ml−1; +++, 6 µg ml−1); AgNP (+, 2 µg ml−1; ++, 4 µg ml−1; +++, 8 µg ml−1); GO+AgNP mixture (+, 1.5 µg ml−1 GO and 2 µg ml−1 AgNP; ++, 3 µg ml−1 GO and 4 µg ml−1 AgNP; +++, 6 µg ml−1 GO and 8 µg ml−1 AgNP), GO-Ag (+, 3.5 µg ml−1; ++, 7 µg ml−1; +++, 14 µg ml−1). Error bars represent standard deviations (n ≥ 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.4. In vitro photothermal-assisted treatment of MDR-2

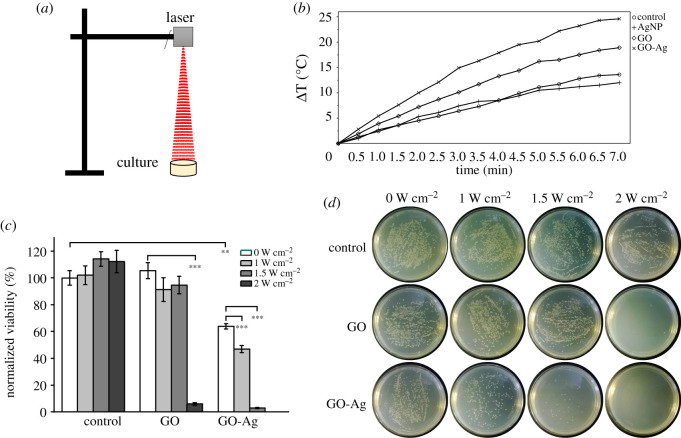

Photothermal treatment of MDR-2 E. coli using GO-Ag nanocomposites was conducted. MDR-2 was selected as it was non-susceptible to more antibiotics and less susceptible to GO-Ag at lower concentration (figure 2b). First, 107–108 CFU ml−1 bacteria were cultured with 7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag nanocomposites or 3 µg ml−1 GO in LB broth for 1 h. Afterwards, 808 nm near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation was exerted continuously on bacteria culture for 7 min, as illustrated in figure 3a. After 6 h incubation, bacteria were collected for cell viability assessment using MTT assay and spread plate method. As shown in figure 3c,d, results of two viability assessment methods were consistent with each other. A total of 6 h incubation time was used because bacteria in control group were in plateau phase. In this case, we could figure out whether bacteria growth was stopped completely after photothermal treatment.

Figure 3.

In vitro photothermal treatment of MDR-2 E. coli. (a) Illustration of photothermal treatment of bacteria in LB broth. (b) Heating curves of nanomaterials (7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag, 4 µg ml−1 GO, 3 µg ml−1 AgNP) dispersed in LB broth, 1.5 W cm−2. (c) Remaining bacteria viability after photothermal treatment, 3 µg ml−1 GO, 7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag. (d) Photos of bacteria colonies on LB agar plates after photothermal treatment. Error bars represent standard deviations (n ≥ 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Before photothermal treatment, NIR heating curves of GO-Ag, GO, AgNP dispersed in LB broth were recorded by thermal camera. Temperature increasement of control, AgNP, GO and GO-Ag were 13.6°C, 12°C, 18.9°C and 24.6°C after 7 min irradiation at 1.5 W cm−2 (figure 3b). As a matter of fact, GO-Ag owned property of converting electromagnetic energy to heat, which might elevate its antibacterial efficiency. In figure 3c, different laser irradiation (1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 W cm−2) had no observable inhibitory effect to MDR-2 E. coli in control groups. Thus, photothermal treatment comparison between GO and GO-Ag was suitable. Since GO content in 7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag nanocomposite was 43%, 4 µg ml−1 GO was used as control. In figure 3c, compared with GO sheets, GO-Ag was more efficient to resist the growth of bacteria at the same power density. This was because heating curves of GO-Ag were above GO at the same power density (electronic supplementary material, figure S3) and GO-Ag could inhibit growth of bacteria even without photothermal treatment. When power density increased to 2 W cm−2, GO heating curve overlaid with 1.5 W cm−2 GO-Ag, and remaining bacteria viabilities were similar for GO and GO-Ag in this condition. As shown in figure 3c, remaining viabilities were 3.0% in GO-Ag group at 1.5 W cm−2, and 6% in GO-treated group at 2 W cm−2. When power density was increased to 2 W cm−2, MDR-2 E. coli could be killed completely in GO-Ag-treated group. However, the remaining viability was 69% without photothermal treatment in GO-Ag group. Thus, efficient antibacterial effect could be achieved with lower concentration of GO-Ag when photothermal treatment was exerted simultaneously.

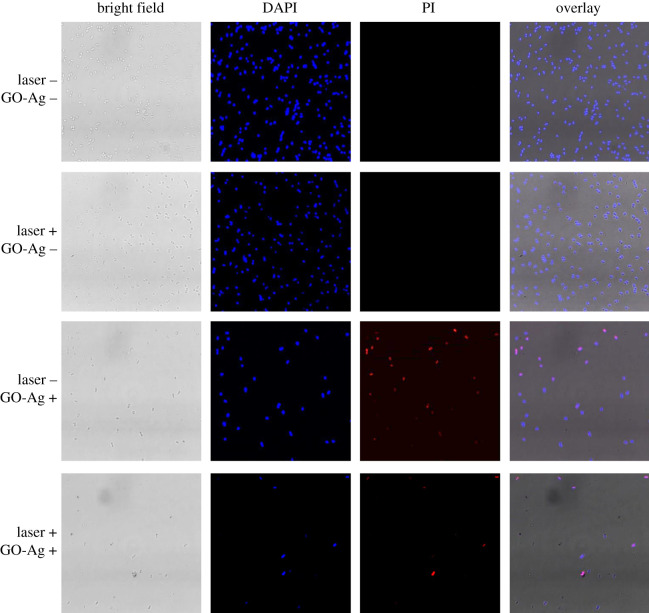

3.5. Characterization of GO-Ag-treated MDR bacteria

The above results demonstrated that GO-Ag nanocomposites were highly effective antibacterial agent, but whether bacteria growth was inhibited temporarily or permanently remained unclear. Fluorescence imaging, a well-accepted qualitative method, was used to distinguish living and non-living bacteria in treated groups (red colour in figure 4) other than efficiency comparison (figure 3). Specifically, compared with million to billion cells used in viability assessment in figure 3, fluorescence images were snapshots of extremely small parts of treated bacteria, which was not suitable for quantitative comparisons. In this experiment, photothermal irradiation and GO-Ag treatment were two variables that influence bacteria viability. Fluorescence imaging was conducted to observe changes of bacteria living status that was induced by these two variables. As shown in figure 4, four groups of bacteria were imaged using fluorescence microscopy. In the two control groups without GO-Ag nanocomposites addition (GO-Ag –), dead cells could hardly be found under microscope and the laser irradiation did not induce bacteria death, which was consistent with results from figure 3b. By contrast, in the group with GO-Ag nanocomposites (GO-Ag +), most of the bacteria were non-living cells. Moreover, in the group with GO-Ag nanocomposites and laser irradiation (GO-Ag +, laser +), fewer cells could be found in comparison with group without laser irradiation (GO-Ag +, laser –). Results indicated that both GO-Ag treatment and photothermal treatment could result in non-living cells.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence imaging of MDR-2 E. coli with and without photothermal treatment. DAPI and PI were used to stain the nuclei acid of bacteria. The difference is DAPI stains all the bacteria while PI can only stain the non-living bacteria. DAPI-stained bacteria emit blue fluorescence light while PI-stained bacteria emit red fluorescence light. ‘Laser +’ and ‘Laser –’ denote the presence and absence of photothermal treatment, ‘GO-Ag +’ and ‘GO-Ag –’ denote the presence and absence of GO-Ag nanocomposites. 1.5 W cm−2, 7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag. Scale bar is 5 µm.

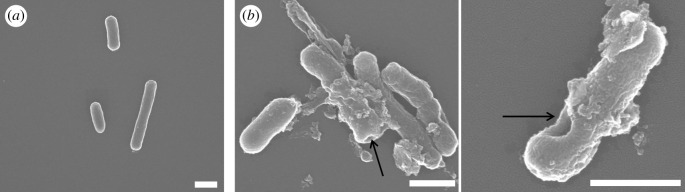

Furthermore, morphology of MDR-2 bacteria was characterized using SEM after treatment with 14 µg ml−1 GO-Ag nanocomposites. As shown by arrows in figure 5, some pits were found on the surface of cell wall, which meant cell walls were disrupted after GO-Ag nanocomposites treatment. While in the control group, cell wall was smooth, and no cell integrity disruption was observed.

Figure 5.

SEM images of MDR-2 E. coli. (a) SEM image of control group without GO-Ag treatment. (b) SEM images of bacteria treated with 14 µg ml−1 GO-Ag. Arrows show disrupted cell wall. Scale bar is 1 µm.

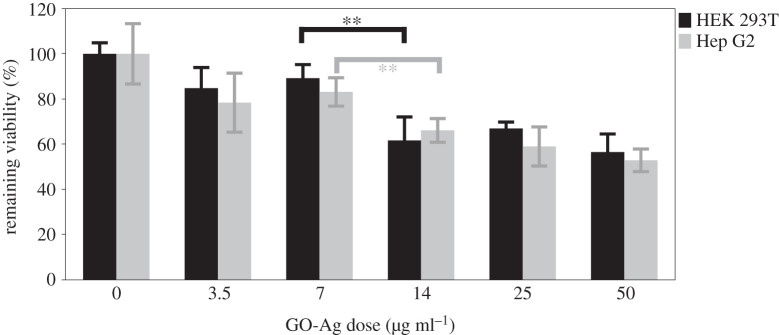

3.6. Cytotoxicity of GO-Ag nanocomposites

Given wide concerns about cytotoxicity of nanomaterials, cytotoxicity of GO-Ag was conducted using HEK 293T and Hep G2 cells. These two cell lines are human origin cells, HEK 293T is a highly transactable derivative of human embryonic kidney 293 cells and Hep G2 is human hepatoma-derived cell line. Results in figure 6 show that cytotoxicity was correlated with dose of GO-Ag; high dose GO-Ag would cause a significant decrease in cell viability. As shown in figure 6, remaining viabilities of HEK 293T and Hep G2 at 14 µg ml−1 were about 61.7 ± 10.4%, 66.1 ± 5.3% and 56.5 ± 8.0%, 52.9 ± 5.0% at 50 µg ml−1. However, remaining viabilities of both cell lines were above 80% when concentration reduced to 7.5 µg ml−1, and MDR-2 E. coli can be completely killed with assistance of photothermal treatment at 7.5 µg ml−1. Which suggested that GO-Ag mediated photothermal combined treatment was a promising method with low cytotoxicity at 7.5 µg ml−1.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity of GO-Ag nanocomposites. HEK 293T and Hep G2 cells viability assessment was conducted using MTT assay after 24 h incubation with GO-Ag nanocomposites. Error bars are standard deviations of five replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

It was reported GO-Ag could not only inhibit growth of non-susceptible bacteria, including Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli [38,46], but also inhibit growth of methicillin-resistant S. aureus [39] and fungus like Candida albicans and Candida tropical [42]. In this work, clinically isolated MDR E. coli was selected as samples to test the antibacterial efficiency of GO-Ag nanocomposites in vitro. It was proved that GO-Ag nanocomposites were effective against MDR E. coli, which broadens its antimicrobial spectrum. Moreover, the most important advance was photothermal treatment was combined for the first time in GO-Ag antibacterial applications.

GO-Ag nanocomposites showed antibacterial effect in both liquid and solid media (table 2 and figure 2). As MIC results showed, 4 µg ml−1 GO-Ag could completely inhibit growth of 104 CFU bacteria on agar plate. In broth, ratio of survival bacteria was less than 5% when 14 µg ml−1 GO-Ag was added into 107–108 CFU ml−1 bacteria culture. AgNPs also showed antibacterial effect, but efficiency was not so obvious. MIC of AgNP was 32 µg ml−1 on agar medium. While 8 µg ml−1 AgNP addition in broth had minor antibacterial effect on two MDR bacteria. GO-treated bacteria, showed no viability decrease trend with increased concentration from 1.5 to 6 µg ml−1, though several published papers reported that GO was an antimicrobial agent. The different antibacterial property of GO might come from difference of material preparation method, dose, material size, culturing condition and sample handling method [47–52].

Higher antibacterial efficiency of GO-Ag nanocomposites can be explained by AgNPs being well distributed on GO sheets, which provided large contact area between bacteria and AgNPs. Compared with GO, AgNPs and mixture of GO and AgNPs, GO-Ag nanocomposite-treated group achieved better antibacterial result at same concentration of Ag or GO, which disclosed existence of synergetic effect that arose from combining GO and AgNPs as composite. And this synergetic effect was consistent with previous reported works [38,39].

Compared with other reported GO-Ag-related antimicrobial applications, photothermal therapy was combined in this study for the first time. An important benefit was that GO-Ag dose could be cut down, which was an advantage for biomedical applications; 7 µg ml−1 GO-Ag could completely killed bacteria in photothermal combined therapy, while 14 µg ml−1 GO-Ag could not completely inhibit MDR bacteria growth. Photothermal-assistant therapy could greatly enhance antibacterial efficiency as GO-Ag possessed advantages of AgNP and GO. AgNP inhibited bacteria growth, while GO sheets absorbed the NIR light and generated heat to help kill bacteria. Another advantage of photothermal therapy was that it could kill MDR bacteria even if bacteria were resistant to GO-Ag. Thus, photothermal-assistant therapy with GO-Ag provides an alternative strategy to solve problems brought by drug-resistant bacteria.

In order to better understand interaction between GO-Ag nanocomposites and bacteria, fluorescence imaging (figure 4) and SEM imaging (figure 5) of treated E. coli were analysed. Fluorescence imaging was used to distinguish living and dead bacteria using optimized PI staining process for bacteria [53]. DAPI was used to stain DNA-containing bacteria regardless of their physiological status, while PI was used to stain membrane-compromised bacteria [54–56]. In fluorescence images, red light emitted from GO-Ag and photothermal-treated groups demonstrated that both GO-Ag nanocomposites and photothermal treatment could damage bacteria integrity. Morphology characterization using SEM confirmed that cell integrity was disrupted by GO-Ag nanocomposites, which was consistent with published results [38,39,46].

Toxicity of engineered nanomaterials is an important consideration for further applications, especially for newly synthesized nanomaterials. Toxicity of GO and AgNPs is widely explored both in vivo and in vitro [57–61]. Cytotoxicity of GO-Ag nanocomposites was also reported by several researchers. De Luna et al. had done comparative toxicity study using GO-Ag and pristine counterparts (GO, AgNP), and viability IC50 value of macrophage cells (J774, peritoneal macrophages) derived from murine were compared. Results showed IC50 of GO, Ag, GO-Ag were 16.9, 8.9 and 2.9 µg ml−1 in macrophage J774 cell after 24 h exposure [62]. Tang et al. reported 80% cell viability remained after 24 h incubation of mammalian cells (HEK 293T, HeLa) and 10 µg ml−1 GO-Ag [38]. In our study, cytotoxicity of GO-Ag was assessed using human-derived liver and kidney cell lines. Results showed more than 80% viability remained for both cell lines, which suggested our synthesized GO-Ag was a great antibacterial agent with low cytotoxicity.

This study provided a facial method to synthesize GO-Ag nanocomposite, which possessed synergetic antibacterial property as well as photothermal property. It provided double insurance to combat traditional antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and achieved enhanced antibacterial efficiency to pathogens with reduced cytotoxicity. Given the excellent antibacterial performance of GO-Ag nanocomposites against widely distributed MDR E. coli bacteria, they will be a useful antimicrobial in future medical applications.

5. Conclusion

Compared with widely used AgNP, GO-Ag nanocomposite showed much better antibacterial efficiency to clinically isolated MDR E. coli. Moreover, photothermal treatment could be combined to further lower the dose to 7 µg ml−1, and MDR E. coli were killed completely with reduced cytotoxicity. Fluorescence imaging and morphology characterization disclosed that bacteria integrity was damaged after treatment with GO-Ag. Given the excellent antibacterial performance of GO-Ag nanocomposites against widely distributed MDR E. coli bacteria, they could be useful antibacterial consumables in future medical applications.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Wu for fruitful discussion.

Data accessibility

Our data are deposited at Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s7h44j133 [63].

Authors' contributions

Y.C. and W.W. contributed equally to this work, prepared all samples and performed experiments. Z.X. and C.J. collected and analysed the data. S.H. and Y.W. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. J.R., S.H. and Y.W. designed the research. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work is supported by Young Project of Wuxi Health and Family Planning Commission (grant no. Q201809).

References

- 1.Czaplewski L, et al. 2016. Alternatives to antibiotics — a pipeline portfolio review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 239–251. ( 10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00466-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenover FC. 2006. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am. J. Infect. Control 34, S3–S10. ( 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.219) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magiorakos AP, et al. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281. ( 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nseir S, et al. 2006. Multiple-drug-resistant bacteria in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Crit. Care Med. 34, 2959–2966. ( 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000245666.28867.C6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herati RS, Blumberg EA. 2012. Losing ground: multidrug-resistant bacteria in solid-organ transplantation. Curr. Opin Infect. Dis. 25, 445–449. ( 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328354f192) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatarelli P, Mikulska M. 2016. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in hematology patients: emerging threats. Future Microbiol. 11, 767–780. ( 10.2217/fmb-2015-0014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. 2015. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 269–284. ( 10.1038/nrmicro3432) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manges AR, Johnson JR, Foxman B, O'Bryan TT, Fullerton KE, Riley LW. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N Engl. J. Med. 345, 1007–1013. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa011265) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linton AH, Howe K, Bennett PM, Richmond MH, Whiteside EJ. 1977. Colonization of human gut by antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli from chickens. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 43, 465–469. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1977.tb00773.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saenz Y, Brinas L, Dominguez E, Ruiz J, Zarazaga M, Vila J, Torres C. 2004. Mechanisms of resistance in multiple-antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli strains of human, animal, and food origins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 3996–4001. ( 10.1128/aac.48.10.3996-4001.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng J, Zhao S, Doyle MP, Joseph SW. 1998. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O157:NM isolated from animals, food, and humans. J. Food Prot. 61, 1511–1514. ( 10.4315/0362-028x-61.11.1511) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bensink JC, Bothmann FP. 1991. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from chilled meat at retail outlets. N. Z. Vet. J. 39, 126–128. ( 10.1080/00480169.1991.35678) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JR, Kuskowski MA, Smith K, O'Bryan TT, Tatini S. 2005. Antimicrobial-resistant and extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in retail foods. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1040–1049. ( 10.1086/428451) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkinson AJ, Micalizzi GB, Graham GM, Bates JB, Costanzo SD. 2007. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in wastewaters, surface waters, and oysters from an urban riverine system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5667–5670. ( 10.1128/aem.00763-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsberg KJ, Reyes A, Wang B, Selleck EM, Sommer MOA, Dantas G. 2012. The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science. 337, 1107–1111. ( 10.1126/science.1220761) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seil JT, Webster TJ. 2012. Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 7, 2767–2781. ( 10.2147/ijn.S24805) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirelkhatim A, Mahmud S, Seeni A, Kaus NHM, Ann LC, Bakhori SKM, Hasan H, Mohamad D. 2015. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nano-Micro Lett. 7, 219–242. ( 10.1007/s40820-015-0040-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu GF, Vary PS, Lin CT. 2005. Anatase TiO2 nanocomposites for antimicrobial coatings. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109, 8889–8898. ( 10.1021/jp0502196) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dizaj SM, Lotfipour F, Barzegar-Jalali M, Zarrintan MH, Adibkia K. 2014. Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 44, 278–284. ( 10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma VK, Yngard RA, Lin Y. 2009. Silver nanoparticles: green synthesis and their antimicrobial activities. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 145, 83–96. ( 10.1016/j.cis.2008.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai MK, Deshmukh SD, Ingle AP, Gade AK. 2012. Silver nanoparticles: the powerful nanoweapon against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 112, 841–852. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05253.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor PL, Ussher AL, Burrell RE. 2005. Impact of heat on nanocrystalline silver dressings. Part I: Chemical and biological properties. Biomaterials 26, 7221–7229. ( 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzman M, Dille J, Godet S. 2012. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 8, 37–45. ( 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas R, Nair AP, Soumya KR, Mathew J, Radhakrishnan EK. 2014. Antibacterial activity and synergistic effect of biosynthesized AgNPs with antibiotics against multidrug-resistant biofilm-forming coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from clinical samples. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 173, 449–460. ( 10.1007/s12010-014-0852-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radzig MA, Nadtochenko VA, Koksharova OA, Kiwi J, Lipasova VA, Khmel IA. 2013. Antibacterial effects of silver nanoparticles on gram-negative bacteria: influence on the growth and biofilms formation, mechanisms of action. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 102, 300–306. ( 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.07.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen M, Yu X, Huo Q, Yuan Q, Li X, Xu C, Bao H. 2019. Biomedical potentialities of silver nanoparticles for clinical multiple drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Nanomater. 2019, 1–7. ( 10.1155/2019/3754018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. 2007. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191. ( 10.1038/nmat1849) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geim AK. 2009. Graphene: status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534. ( 10.1126/science.1158877) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu YW, Murali S, Cai WW, Li XS, Suk JW, Potts JR, Ruoff RS. 2010. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv. Mater. 22, 3906–3924. ( 10.1002/adma.201001068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji H, Sun H, Qu X. 2016. Antibacterial applications of graphene-based nanomaterials: recent achievements and challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 105, 176–189. ( 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markovic ZM, et al. 2018. Photo-induced antibacterial activity of four graphene based nanomaterials on a wide range of bacteria. RSC Adv. 8, 31 337–31 347. ( 10.1039/c8ra04664f) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Y, Yang X, Tan X, Xu L, Liu Z, Xiao J, Peng R. 2016. Functionalized graphene oxide in microbial engineering: an effective stimulator for bacterial growth. Carbon 103, 172–180. ( 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.03.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz ON, Fernando KAS, Wang BJ, Brown NA, Luo PG, McNamara ND, Vangsness M, Sun YP, Bunker CE. 2011. Graphene oxide: a nonspecific enhancer of cellular growth. ACS Nano 5, 8100–8107. ( 10.1021/nn202699t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao J, Bao F, Feng L, Shen K, Zhu Q, Wang D, Chen T, Ma R, Yan C. 2011. Functionalized graphene oxide modified polysebacic anhydride as drug carrier for levofloxacin controlled release. RSC Adv. 1, 1737–1744. ( 10.1039/c1ra00029b) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao L, Sun J, Liu L, Hu R, Lu H, Cheng C, Huang Y, Wang S, Geng J. 2017. Enhanced photothermal bactericidal activity of the reduced graphene oxide modified by cationic water-soluble conjugated polymer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 5382–5391. ( 10.1021/acsami.6b14473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu M-C, Deokar AR, Liao J-H, Shih P-Y, Ling Y-C. 2013. Graphene-based photothermal agent for rapid and effective killing of bacteria. ACS Nano 7, 1281–1290. ( 10.1021/nn304782d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaworski S, et al. 2018. Graphene oxide-based nanocomposites decorated with silver nanoparticles as an antibacterial agent. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 13, 116. ( 10.1186/s11671-018-2533-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang J, Chen Q, Xu L, Zhang S, Feng L, Cheng L, Xu H, Liu Z, Peng R. 2013. Graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite as a highly effective antibacterial agent with species-specific mechanisms. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 3867–3874. ( 10.1021/am4005495) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazarin de Moraes AC, Lima BA, de Faria AF, Brocchi M, Alves OL. 2015. Graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite as a promising biocidal agent against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 10, 6847–6861. ( 10.2147/ijn.S90660) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu W-P, Zhang L-C, Li J-P, Lu Y, Li H-H, Ma Y-N, Wang W-D, Yu S-H. 2011. Facile synthesis of silver@graphene oxide nanocomposites and their enhanced antibacterial properties. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 4593–4597. ( 10.1039/c0jm03376f) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad K, et al. 2017. Synergic bactericidal effects of reduced graphene oxide and silver nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Sci. Rep. 7, 1591. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-01669-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Wang X, Chen F, Zhang C, Zhi X, Wang K, Cui D. 2013. The antifungal activity of graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites. Biomaterials 34, 3882–3890. ( 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian T, et al. 2014. Graphene-based nanocomposite as an effective, multifunctional, and recyclable antibacterial agent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 8542–8548. ( 10.1021/am5022914) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hendry AT, Stewart IO. 1979. Silver-resistant enterobacteriaceae from hospital patients. Can. J. Microbiol. 25, 915–921. ( 10.1139/m79-136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finley PJ, Norton R, Austin C, Mitchell A, Zank S, Durham P. 2015. Unprecedented silver resistance in clinically isolated enterobacteriaceae: major implications for burn and wound management. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 4734–4741. ( 10.1128/aac.00026-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma J, Zhang J, Xiong Z, Yong Y, Zhao XS. 2011. Preparation, characterization and antibacterial properties of silver-modified graphene oxide. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 3350–3352. ( 10.1039/c0jm02806a) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akhavan O, Ghaderi E. 2010. Toxicity of graphene and graphene oxide nanowalls against bacteria. ACS Nano 4, 5731–5736. ( 10.1021/nn101390x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu S, Zeng TH, Hofmann M, Burcombe E, Wei J, Jiang R, Kong J, Chen Y. 2011. Antibacterial activity of graphite, graphite oxide, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide: membrane and oxidative stress. ACS Nano 5, 6971–6980. ( 10.1021/nn202451x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He JL, Zhu XD, Qi ZN, Wang C, Mao XJ, Zhu CL, He ZY, Lo MY, Tang ZS. 2015. Killing dental pathogens using antibacterial graphene oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 5605–5611. ( 10.1021/acsami.5b01069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Peng H, Wang X, Shao F, Yuan Z, Han H. 2014. Graphene oxide exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacterial phytopathogens and fungal conidia by intertwining and membrane perturbation. Nanoscale 6, 1879–1889. ( 10.1039/c3nr04941h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perreault F, de Faria AF, Nejati S, Elimelech M. 2015. Antimicrobial properties of graphene oxide nanosheets: why size matters. ACS Nano 9, 7226–7236. ( 10.1021/acsnano.5b02067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yousefi M, Dadashpour M, Hejazi M, Hasanzadeh M, Behnam B, de la Guardia M, Shadjou N, Mokhtarzadeh A. 2017. Anti-bacterial activity of graphene oxide as a new weapon nanomaterial to combat multidrug-resistance bacteria. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 74, 568–581. ( 10.1016/j.msec.2016.12.125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams SC, Hong Y, Danavall DCA, Howard-Jones MH, Gibson D, Frischer ME, Verity PG. 1998. Distinguishing between living and nonliving bacteria: evaluation of the vital stain propidium iodide and its combined use with molecular probes in aquatic samples. J. Microbiol. Methods. 32, 225–236. ( 10.1016/s0167-7012(98)00014-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopezamoros R, Comas J, Vivesrego J. 1995. Flow cytometric assessment of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium starvation-survival in seawater using rhodamine-123, propidium iodide, and oxonol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2521–2526. ( 10.1128/AEM.61.7.2521-2526.1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sgorbati S, Barbesti S, Citterio S, Bestetti G, DeVecchi R. 1996. Characterization of number, DNA content, viability and cell size of bacteria from natural environments using DAPI/PI dual staining and flow cytometry. Minerva Biotechnol. 8, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jepras RI, Carter J, Pearson SC, Paul FE, Wilkinson MJ. 1995. Development of a robust flow cytometric assay for determining numbers of viable bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2696–2701. ( 10.1128/AEM.61.7.2696-2701.1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dos Santos CA, Seckler MM, Ingle AP, Gupta I, Galdiero S, Galdiero M, Gade A, Rai M. 2014. Silver nanoparticles: therapeutical uses, toxicity, and safety issues. J. Pharm. Sci. 103, 1931–1944. ( 10.1002/jps.24001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.da Silva Martins LH, Rai M, Neto JM, Gomes PWP, da Silva Martins JH. 2018. Silver: biomedical applications and adverse effects. In Biomedical applications of metals, pp. 113–127. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang K, Zhang S, Zhang G, Sun X, Lee S-T, Liu Z. 2010. Graphene in mice: ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 10, 3318–3323. ( 10.1021/nl100996u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang K, Ruan J, Song H, Zhang JL, Wo Y, Guo SW, Cui DX. 2011. Biocompatibility of graphene oxide. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 8 ( 10.1007/s11671-010-9751-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang YL, Yang ST, Liu JH, Dong E, Wang YW, Cao AN, Liu YF, Wang HF. 2011. In vitro toxicity evaluation of graphene oxide on A549 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 200, 201–210. ( 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.11.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Luna LAV, de Moraes ACM, Consonni SR, Pereira CD, Cadore S, Giorgio S, Alves OL. 2016. Comparative in vitro toxicity of a graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite and the pristine counterparts toward macrophages. J. Nanobiotechnol. 14, 17 ( 10.1186/s12951-016-0165-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Y, Wu W, Xu Z, Jiang C, Han S, Ruan J, Wang Y. 2020. Data from: Photothermal-assisted antibacterial application of GO-Ag nanocomposites against clinical isolated MDR. Dryad Digital Repository ( 10.5061/dryad.s7h44j133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Chen Y, Wu W, Xu Z, Jiang C, Han S, Ruan J, Wang Y. 2020. Data from: Photothermal-assisted antibacterial application of GO-Ag nanocomposites against clinical isolated MDR. Dryad Digital Repository ( 10.5061/dryad.s7h44j133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Our data are deposited at Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s7h44j133 [63].