Different mechanisms govern the first and second steps of IgH gene recombination.

Abstract

Immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) genes are assembled by two sequential DNA rearrangement events that are initiated by recombination activating gene products (RAG) 1 and 2. Diversity (DH) gene segments rearrange first, followed by variable (VH) gene rearrangements. Here, we provide evidence that each rearrangement step is guided by different rules of engagement between rearranging gene segments. DH gene segments, which recombine by deletion of intervening DNA, must be located within a RAG1/2 scanning domain for efficient recombination. In the absence of intergenic control region 1, a regulatory sequence that delineates the RAG scanning domain on wild-type IgH alleles, VH and DH gene segments can recombine with each other by both deletion and inversion of intervening DNA. We propose that VH gene segments find their targets by distinct mechanisms from those that apply to DH gene segments. These distinctions may underlie differential allelic choice associated with each step of IgH gene assembly.

INTRODUCTION

B lymphocyte antigen receptors, or immunoglobulins (Igs), are composed of two heavy chain (IgH) and two light chain (IgL) polypeptides. The ability of B lymphocytes to recognize and mount immune responses against a wide variety of pathogens lies in the diversity of Igs expressed on their cell surface. Antibody diversity is generated during B cell development by a cut-and-paste gene rearrangement process known as VDJ recombination (1). At the IgH locus, this involves two rearrangement events (2, 3). The first juxtaposes 1 of 8 to 12 diversity (DH) gene segments to one of 4 joining (JH) gene segments in the mouse to create a DJH rearranged allele. DH rearrangements are believed to occur simultaneously on both alleles. The second rearrangement step fuses one of approximately 100 variable (VH) gene segments to the preformed DJH junction to produce a VDJ rearranged allele that can encode IgH protein. The strict order of IgH gene assembly is highlighted by the absence of VH recombination to unrearranged DH gene segments on wild-type (WT) IgH alleles. In addition, VH-to-DJH recombination has been proposed to occur asynchronously on the two alleles. IgH diversity is generated combinatorially (by randomly juxtaposing VH, DH, and JH gene segments) and by features of the recombination reaction that introduce junctional diversity that is not encoded in the genome. A critical aspect of IgH gene assembly is availability of all gene segments to participate in recombination. This is imposed by epigenetic mechanisms directed by regulatory sequences within the locus.

Two especially important regulatory sequences are the intronic enhancer, Eμ, and the intergenic control region 1 (IGCR1) (Fig. 1A). IgH alleles that lack Eμ have substantially reduced levels of activation-associated histone modifications in the DQ52-JH region, show reduced transcription through this region, and undergo lower levels of DH recombination compared to WT IgH alleles (4–7). VH recombination is barely detectable on Eμ-deficient alleles. Mutation of two CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor)–binding elements (CBEs) within IGCR1 disrupts the normal order of IgH gene rearrangements and severely restricts VH utilization (8, 9). On such alleles VH genes recombine to unrearranged DH gene segments rather than exclusively to preformed DJH junctions, and the vast majority of rearrangements involve the 3′-most proximal VH gene segment VH81X (10). Notably missing are members of the largest distal VHJ558 gene family that dominate the WT B cell repertoire, resulting in marked reduction of combinatorial diversity. CBEs have also been shown to regulate V(D)J recombination at other antigen receptor loci (11–16). Similarly, CTCF deletion results in an altered Vκ repertoire at the Igκ light chain gene locus (17).

Fig. 1. Chromatin accessibility and transcription on WT and IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles.

(A) Schematic map of IgH locus. Regulatory sequences are shown as colored ovals. Gene segments are indicated as colored boxes. Black lines under schematic refer to amplicons used in (D) to (G). (B) Capture Hi-C of WT (left) and IGCR1-deleted (middle) IgH alleles. Interacting regions are highlighted within dashed lines. Difference interaction map between WT and IGCR1-deleted IgH alleles is shown in the right. Decrease (blue) or increase (red) on IGCR1-deleted alleles is indicated. Position and orientation of CTCF-bound sites are indicated below heatmap (47). See also fig. S1A. (C) ATAC-seq assays of WT and IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles are shown (chr12: 114,554,576 to 114,839,712, mm9). Colored rectangles mark ATAC peaks that are (i) reduced by IGCR1 mutation (red), (ii) increased by IGCR1 mutation (green), or (iii) unaffected by IGCR1 mutation (black). Differential chromatin accessibility was quantified on the basis of moderated t tests using R package limma [*adjusted P value (false discovery rate) < 0.01]. Genomic localization and statistics of peaks are provided in fig. S1C. (D to G) RNA analyses of WT and IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles. Data are shown as means ± SEM of two (D, F, and G) or three (E) independent experiments.

Combined analyses of Eμ- and IGCR1-deficient alleles have led to the following model to understand how these regulatory elements coordinately control IgH gene rearrangements. On WT alleles, Eμ interacts with IGCR1, thereby cloistering all DH gene segments within a 60-kb chromatin loop (8, 18). In this configuration the 5′-most DH gene segment (DFL16.1) is located close to the recombination activating gene product (RAG1 and RAG2)–rich recombination center (RC) (19) that forms over the JH gene segments. The resulting spatial proximity of DFL16.1 and JH gene segments may account for increased utilization of DFL16.1 in DH rearrangements (18, 20). This configuration also restricts RAG1/2 tracking from the JH-associated RC to a segment of the IgH locus that contains only DH gene segments (2, 10, 21), thereby ensuring that DH rearrangements occur first. Introduction of a VH gene segment within this domain results in its premature rearrangement (22). Thus, Eμ/IGCR1 interactions direct order and frequency of DH recombination, as well as the using of an extensive repertoire of VH gene segments.

Disruption of Eμ/IGCR1 interactions releases Eμ to interact with the next compatible looping site, which is a CTCF-bound site that lies closest to the 3′-most functional VH gene segment VH81X (23, 24). The new 150-kb Eμ-VH81X loop locates VH81X rather than DFL16.1 close to the JH-associated RC, resulting in increased recombination of VH81X and decreased recombination of DFL16.1. These changes in recombination frequencies occur without alteration of spacing between the gene segments on linear DNA. However, the effects of Eμ/VH81X interaction on IgH locus structure differ in two respects from Eμ/IGCR1 interaction. First, the distal VH J558 genes are no longer in spatial proximity of the DH-CH part of the locus on Eμ-VH81X looped alleles (24). This may underlie reduced utilization of VHJ558 family genes in VH recombination. Second, RAG1/2 proteins accumulate close to VH81X on such alleles, resulting in an expanded RC compared to one that forms on WT IgH alleles (24). This may, in part, explain the especially high levels of VH81X recombination on IGCR1-mutated alleles.

Here, we further explored functional consequences of alternate Eμ-dependent chromatin looping on IGCR1-mutated alleles. We demonstrate that placement of an infrequently used DH gene segment, DST4.2 (which is located midway between DFL16.1 and VH81X) within the Eμ/VH81X loop on IGCR1-mutated alleles activates it to recombine by deletion to JH gene segments. However, VH recombination to unrearranged DH gene segments occurs by both deletional and inversional mechanisms. This was true of VH81X (on IGCR1-deficient alleles), as well as other VH gene segments located 5′ of VH81X that were forced to recombine by sequential deletion of CTCF sites in the proximal VH region. These observations provide the first example of inversional VH recombination and associated signal-end junction products at the IgH locus and indicate that RSS (recombination signal sequence) choice for VH recombination is regulated differently from DH-to-JH recombination. These distinct mechanisms of DH and VH recombination may underlie differential allelic choice associated with each step of IgH gene assembly.

RESULTS

DST4.2 utilization on IGCR1-deficient IgH alleles

We previously showed Eμ loops to a CTCF-bound site close to the 3′-most functional VH gene, VH81X, on IgH alleles that lack IGCR1 (24). To obtain an unbiased view of chromatin structural changes associated with IGCR1 deficiency, we carried out locus-specific capture Hi-C with cells containing WT or IGCR1-deleted IgH alleles [D345/IGCR1−/−(1)] using Agilent SureSelectXT custom probes spanning the IgH locus (mm10, chr12: 113,201,001 to 116,030,000). Eμ interacted with the 3′ end of the IgH locus (3′CBE) as well as IGCR1 on WT alleles, with the latter marking off a 60-kb topologically associated domain (sub-TAD) (Fig. 1B, left). In addition, we found that proximal VH genes also interacted with IGCR1 and 3′CBE but less so with Eμ. These signals likely represent previously described Eμ-independent forms of IgH locus compaction (20, 25). IGCR1 deletion attenuated its interactions with Eμ, 3′CBE and proximal VH genes (oval circle, Fig. 1B, middle and right, highlighted in blue). Instead, Eμ associated with proximal VH genes resulting in the generation of a domain of heightened interactions in the intervening genomic region between VH and IGCR1 (polygon, Fig. 1B, right, highlighted in red). Proximal VH-3′CBE interaction remains clearly evident on IGCR1-deleted alleles (Fig. 1B, middle). The sub-TAD between Eμ and IGCR1 was discernible, albeit at lower intensity, even on IGCR1-deleted alleles. We hypothesize that this may reflect Eμ interactions with multiple DH-associated promoters that lie in this 60-kb region (25). Similar results were obtained for Hi-C with normalized contact frequency analyses (fig. S1A). We conclude that multiple levels of three-dimensional (3D) structural changes accrue on IGCR1-deleted IgH alleles.

We also used assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) to query changes in accessible chromatin caused by IGCR1 deficiency. ATAC peaks in the Eμ-DQ52 and 3′ part of the locus were unchanged by the IGCR1 mutation (Fig. 1C, black boxes), whereas peaks corresponding to IGCR1 were absent on mutated alleles (Fig. 1C, red boxes). A third hypersensitive site upstream of DFL16.1 (5′DFL16.1) (26) was also absent on IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles. Conversely, ATAC-sensitive regions in the proximal VH region were discernibly increased (labeled VH81X and Q52.2.4) on IGCR1-mutated alleles (Fig. 1C, green boxes; quantitated in fig. S1), likely due to spatial proximity to Eμ. No differences were observed further 5′ in the VH region (fig. S1B). We also noted increased transposase accessibility in a region between DFL16.1 and VH81X that gained Hi-C interactions on IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles (Fig. 1C and fig. S1C, labeled DST4.2). Increased ATAC sensitivity of this region correlated with increased transcription near DST4.2 on IGCR1-mutated alleles (Fig. 1, D and E). Similar trends were observed in two additional lines that lacked IGCR1 (Fig. 1, F and G). These observations demonstrate that loss of IGCR1 activates transcription and increases transposase accessibility of remote DH gene segments.

DH gene segments are flanked by two recombination signal sequences with 12–base pair (bp) spacers (12-RSS) that could recombine with JH-associated 23-RSS by either deletional (using the 3′-DH RSS) or inversional (using the 5′-DH RSS) mechanisms. However, DH recombination on WT alleles proceeds overwhelmingly by deletion (21, 27, 28). This has been attributed to unidirectional tracking of RAG1/2 from the JH-associated RC (2, 10, 14, 21, 23). To determine whether chromatin changes in the DST4.2 region were also reflected in recombination potential, we assayed DH rearrangements on WT and IGCR1-deficient IgH alleles by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Fig. 2A, top line). Increased ATAC sensitivity of DST4.2 was accompanied by its increased recombination to JH gene segments in primary bone marrow pro–B cells carrying IGCR1-deleted IgH alleles (Fig. 2A, left) or in IGCR1-mutated pro–B cell lines induced to undergo DH recombination by transduction of RAG2 (Fig. 2A, right). These rearrangements occurred by deletion of intervening DNA and were undetectable on WT IgH alleles. By contrast, DSP2 rearrangements by deletion were evident on both WT and IGCR1-deficient alleles (Fig. 2A and fig. S2). We did not detect rearrangements of DMB1 and DFL16.3 gene segments that are located close to DST4.2, possibly because of the poor quality of associated RSSs according to recombination information content score (table S1). We also tested whether DST4.2 recombined by inversion and found no evidence for this (fig. S2). Thus, increased ATAC sensitivity near DST4.2 correlated with its increased utilization in DH-to-JH recombination. These observations may also explain low-level rearrangements of DH gene segments in the VH-DFL16.1 intergenic region on IGCR1-mutated alleles that carry DFL16.1-JH3 junctions (10).

Fig. 2. Recombination features of DST4.2 and DSP2 gene segments on WT and IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles.

(A) IgH locus schematic showing location and orientation of primers used in the recombination assay. Rearrangements were assayed in bone marrow pro–B cells (B220+IgM−CD43+) purified from WT and IGCR1-deficient mice (left) and in pro–B cell lines (right). ROSA26 served as the loading control. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Recombination efficiency of 5′- and 3′-DH RSSs. Line 1 shows the organization of RSSs. 12- and 23-RSSs are shown as yellow and blue triangles, respectively. Recombination reporters contained an inverted EGFP gene flanked by a constant 23-RSS (from Jκ1) and test 12-RSSs from different DH gene segments (line 2). RAG1/2-induced recombination (line 3) permits EGFP expression (line 4). (C) Bar plots of the recombination efficiency of 5′- and 3′-DH RSSs. Controls include GFP expression from a reporter that lacks a functional 12-RSS (control 1) or in the absence of cotransfected RAG1/2 (control 2). (D) Ratio of 5′- or 3′-RSS utilization of indicated DH gene segments in 293T cotransfection assays. (E) Recombination efficiency assay in a RAG1/2-expressing pre–B cell line. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

One of the hallmarks of IGCR1-mutated alleles is recombination of VH81X to unrearranged DQ52 gene segments (8). Because DST4.2 recombined to JH gene segments on IGCR1-mutated alleles, we questioned whether it was also available for VH recombination. VH81X-DST4.2 rearrangements were detected in primary pro–B cells or pro–B cell lines with IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles (Fig. 2A). We conclude that DST4.2 is excluded from recombination by Eμ/IGCR1 interactions; Eμ desequestration on IGCR1-mutated alleles permits DST4.2 recombination to VH gene segments that lie 5′ and to JH gene segments that lie 3′. This gain in recombination potential occurs without changes in distance between gene segments on linear DNA and therefore likely arises from observed changes in 3D chromatin organization.

Strength of 5′- and 3′-DH RSSs

Predominantly, deletional recombination of DST4.2 could be due to intrinsic differences in the strength of its 5′- and 3′-RSSs or may be imposed by RAG tracking from JH-associated RSS as proposed for classical DH gene segments (10, 14, 23). To distinguish between these possibilities, we evaluated intrinsic RSS strength using a retroviral recombination reporter developed by Sleckman and colleagues (29, 30). For this, we flanked an inverted green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene with a 23-RSS from Jκ1 and 12-RSS from various DH gene segments (Fig. 2B). Inversional recombination between RSSs results in EGFP expression, while Thy1.2 expression monitors transduction efficiency (Fig. 2B). This experimental design differed from one pioneered by Gauss and Lieber (31) by evaluating 5′- and 3′-DH RSS strengths in identical rather than in competitive contexts. We assayed recombination in 293T cells that were cotransfected with recombination reporters and expression vectors for RAG1 and RAG2 or in a pre–B cell line using endogenous RAG proteins (fig. S3). As controls, we used a reporter that contained a nonfunctional 12-RSS (control 1) or left out RAG expression vectors (control 2). In both assays we found that 5′- and 3′-RSSs of DST4.2 were comparably active, although weaker than those of the classical DFL16.1 and DSP2.9 gene segments (Fig. 2, C and D, and table S1). However, 3′-RSSs of both DFL16.3 and DMB1 gene segments, which are located close to DST4.2, were nonfunctional (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained with integrated recombination reporter plasmids in a pre–B cell line that expresses RAG proteins (Fig. 2E).

To further explore the relationship between RSS strength and recombinational choice, we compared the strengths of RSSs that flank other DH gene segments. We found that the 3′-RSS of DQ52, the 3′-most gene segment, was approximately fivefold stronger than its 5′-RSS (Fig. 2, C and D). The difference between 5′- and 3′-RSSs of DFL16.1 and DSP2.9 gene segments was much less, ranging from 1.5 to 2 folds in favor of the 3′-RSS (Fig. 2, C to E). By contrast, the 3′-RSS of DST4.3 gene segment that lies between DQ52 and the DSP2 repeats was much weaker than its 5′-RSS, which may contribute to its infrequent utilization on WT alleles. These observations indicate that recombinational strength of conventional DH gene segments is skewed toward the 3′-RSS as previously noted (31), although the difference between 5′- and 3′-RSSs is especially marked for DQ52. We conclude that deletional preference of DST4.2 is not due to an especially strong 3′-RSS. Rather, it is likely the result of RAG1/2 tracking as proposed for recombinational preference of DFL16.1 and DSP2 gene segments.

Inversional recombination of VH81X on the IGCR1-deficient IgH alleles

On WT IgH alleles, VH recombination occurs precisely to the 5′-RSS associated with the rearranged DJH junction but not to unrearranged DH gene segments (fig. S4A). Because of the orientation of germline VH gene segments, this reaction only proceeds by deletion of intervening DNA. Thus, inversional VH recombination is excluded by the strict rearrangement order of VH and DH gene segments and has never been observed. A hallmark of IGCR1-mutated alleles is that the VH81X gene segment rearranges to germline DH gene segments, especially DQ52 that is located closest to the RC. This occurs to the 5′-DQ52 RSS by deletion of intervening DNA (8). However, VH81X rearrangements to germline DH gene segments could, in principle, also occur by inversional mechanism to the 3′-DH RSS, which is unavailable at DJH junctions. IGCR1-mutated alleles also have substantial RAG1/2 binding near VH81X, leading us to consider additional effects of inappropriate RC formation on such alleles. In particular, we tested whether VH81X rearrangement to germline DH gene segments was restricted to deletional recombination on IGCR1-mutated alleles. For this, we designed primer combinations that could detect both deletional and inversional recombination of VH81X to DQ52 (Fig. 3A). We first tested amplification efficiencies of these primer combinations using synthetic recombination products that encompassed 60 nucleotides around each primer. PCR analysis of serially diluted recombination products showed that primers designed to detect deletional (F1/R1) or inversional (F1/F2) coding joints were of comparable efficiency (fig. S4B).

Fig. 3. Inversional recombination of VH81X to germline DH gene segments.

(A) Schematic representation of VH81X rearrangements to 5′- and 3′-RSS of DQ52 gene segment by deletion (orange arrow) or inversion (black arrow). Locations and orientation of primers used to assay recombination are indicated. (B) Recombination assays of DQ52 by deletion or inversion from pro–B cell lines expressing RAG2 (top) or from bone marrow pro–B cells (bottom). Fivefold increasing amounts of genomic DNA starting at 8 ng (from cell lines) and 4 ng (from primary pro–B cells) were used as templates. ROSA26 served as the loading control. Data shown are representative of two biological replicate experiments. (C) Signal-end junctions were assayed by PCR as described for (B) using primers R1 and R2. (D to F) VH81X rearrangements to DSP2 gene segments (D) were assayed for inversional or deletional mechanisms (E) and signal-end junctions (F) as described for (A) to (C). ROSA26 served as the loading control. Data shown are representative of two biological replicate experiments.

We then used these primers to query genomic DNA isolated from a pro–B cell line with IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles or from bone marrow–derived pro–B cells with IGCR1-deleted IgH alleles. Coding joint formation by inversion between VH81X and DQ52 was easily detected in both genomic DNA samples with IGCR1-mutated alleles but not from corresponding controls with WT IgH alleles (Fig. 3B). Levels of inversional versus deletional recombination were quite comparable in bone marrow pro–B cells (Fig. 3B, compare F1/F2 versus F1/R1 products). We verified that these primer combinations captured predicted recombinant alleles by cloning and sequencing recombination products (fig. S4, C to E). Recombination by inversion also leaves behind the reaction by-product (Fig. 3A, right), two RSSs joined at the heptamer (32), which is barely observed in WT splenic B cells (28). We used primer pairs R1/R2 to detect such by-products of inversional VH81X to DQ52 rearrangements. These primers generated the expected amplicon when used with genomic DNA from pro–B cells that carried IGCR1-mutated but not WT IgH alleles (Fig. 3C). Cloning and sequencing confirmed perfect heptamer-to-heptamer ligation as the major amplification product (fig. S4F). These observations demonstrate that (i) VH81X recombines to the 5′- or 3′-RSS of germline DQ52 with comparable efficiency and (ii) 12/23 RSS signal-end heptamer-heptamer junctions can be easily detected on IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles.

To determine whether this was a general feature of VH81X recombination on IGCR1-deleted alleles, we designed primers to probe VH81X rearrangements to germline DSP2 gene segments (Fig. 3D). These primer combinations were also tested with synthetic recombination products so that deletional and inversional recombination could be queried with comparable efficiency (fig. S4B). Amplicons corresponding to coding joint formation by inversion were easily detected in genomic DNA from a pro–B cell line and primary bone marrow pro–B cells that carried IGCR1-mutated alleles but not WT alleles (Fig. 3E). We also observed 12/23 RSS signal-end junctions as recombination by-products only in IGCR1-mutated pro–B cell DNA (Fig. 3F). Cloning and sequencing validated these amplicon assignments (fig. S4, G to J). We conclude that loss of Eμ/IGCR1 interactions promotes VH81X rearrangements to germline DH gene segments by both deletion and inversion. These observations are the first example of inversional VH recombination at the IgH locus.

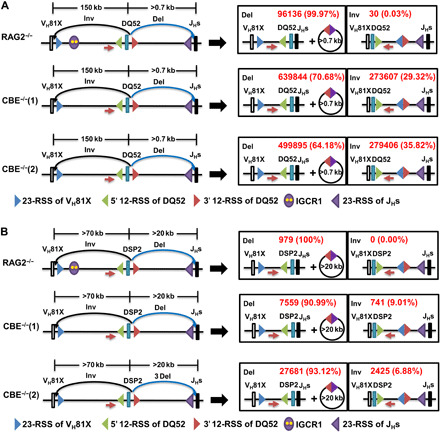

3′-DH RSS utilization on IGCR1-deficient IgH alleles by deletion and inversion

As an independent measure of DH RSS choice during VH to DH rearrangements, we used a modified linear amplification–mediated high-throughput genomic translocation sequencing (LAM-HTGTS) protocol (33) to quantify rearrangements. For this, primers located before the 5′-RSSs of DQ52 (Fig. 4A) or DSP2 (Fig. 4B) gene segments were used to generate size-selected libraries from genomic DNA obtained from cells that contained WT or IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles. This experimental design queried the relative use of the 3′-DH RSS to recombine with JH gene segments (by deletion) or to VH81X gene segment (by inversion) as reflected in sequences downstream of the bait primer. We found close to 30% utilization of the 3′-RSS of DQ52 for VH joining in two lines with IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles (Fig. 4A, right). By comparison, the vast majority of 3′-DH RSS rearrangements on WT alleles occurred to JH gene segments. Though the frequency of 3′ DSP2 RSS rearrangement to VH81X was lower (7 to 9% of sequenced junctions), these rearrangements occurred exclusively on IGCR1-mutated alleles (Fig. 4B, right). The lower proportion of 3′ DSP2 RSS utilization for rearrangements to VH81X compared to DQ52 may reflect spatial proximity of VH81X to DQ52 via Eμ-VH81X looping. In addition, DSP2 to JH rearrangements that occur within the RAG scanning domain are likely to be more efficient than DSP2 rearrangements to VH gene segments that lie outside this domain. These observations substantiate the idea that VH to DH rearrangements can occur by deletion or inversion.

Fig. 4. Inversional and deletional recombination of 3′-RSS of DQ52 and DSP2 on WT and IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles.

Schematic representation of 3′-RSS of DQ52 (A) and DSP2 (B) rearrangements to VH81X gene segment by inversion (black arrows) or to JHs gene segments by deletion (blue arrows), respectively (left). Products of each form of rearrangements are shown to the right. RAG2-deficient pro–B cell lines with WT or IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles [CBE−/−(1) and CBE−/−(2)] were infected with a Rag2-expressing lentivirus, followed by genomic DNA purification after 14 days of selection with puromycin. LAM-HTGTS experiments were carried out as previously described (33, 39) with baits (red arrows) located 50- to 100-bp upstream of DQ52 (A) or DSP2 (B). Restriction enzyme Sacl-HF (R3156S, NEB) and BseYI (R0635S, NEB) were used to remove germline DNA with DQ52 and DSP2 as bait, respectively. Total reads were aligned to detect recombination by deletion to JHs and by inversion to VH81X. The lower reads of 3′ DSP2 RSS utilization compared to DQ52 gene may be due to inefficient restriction of germline DSP2 fragments during library preparation. Average reads and percentages from two independent experiments are shown in red.

Inversional recombination of other VH genes

The VH81X gene segment has some unique recombination features, such as its dominant use during B cell development in the fetus (34–37). To investigate whether VH81X recombination by inversion reflected a mechanistic quirk that was specific for this gene segment, we used IGCR1-mutated cell lines in which other proximal VH gene segments were induced to undergo recombination by sequential deletion of associated CBEs (Fig. 5A) (24). Loss of CTCF site C1 plus a part of VH81X leads to dominant use of the next available VH gene segment, VHQ52.2.4. A larger deletion leads to dominant use of the next VH gene segment, VH7183.4.6. These cell lines allowed us to unequivocally determine whether these upstream gene segments were also capable of recombining by inversion in the absence of IGCR1. Using the same experimental design as for VH81X rearrangements, we probed VHQ52.2.4 (Fig. 5, B and C) and VH7183.4.6 (Fig. 5, D and E) rearrangements by deletion or inversion to germline DQ52 or DSP2 gene segments. Inversional coding joint recombination events were easily evident for both additional VH gene segments by the PCR assay (Fig. 5, B to E, top) and verified by cloning and sequencing of amplification products (figs. S5, F, G, I, and J, and S6, C, D, F, and G). We also observed 12/23 RSS signal-end junctions in both cases as additional evidence for inversional genomic rearrangements [Fig. 5, B to E (bottom), and figs. S5, H and K, and S6, E and H]. Comparable amplification efficiencies of these primers were established using synthetic recombination products (figs. S5E and S6B). A second independent cell clone of C1-mutated alleles showed similar results (fig. S5, A to D). These observations indicate that the property of inversional recombination is not restricted to VH81X, rather it applies to VH gene segments that are induced to undergo premature rearrangement to germline DH gene segments by loss of a functional IGCR1.

Fig. 5. 5′ and 3′ 12-RSS utilization in VHQ52.2.4 or VH7183.4.6-DH recombination.

(A) Schematic of the 3′ IgH locus CTCF-binding sites (24) and mutations produced by CRISPR-Cas9 in the context of the IGCR1 mutated cell line CBE−/−(1). (B and D) Rearrangements assays of VHQ52.2.4 (B) or VH7183.4.6 (D) to 5′- or 3′-RSS of DQ52 by deletion (orange arrows) or inversion (black arrows), respectively. Locations and orientation of primers used to assay recombination are indicated, together with the 23-RSS of VHQ52.2.4 (B) or VH7183.4.6 (D) (blue triangles) and 12-RSSs flanking DQ52 gene segments (green and red triangles). Each set of three lanes contains fivefold increasing amounts of genomic DNA starting at 8 ng (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18). ROSA26 was used as the loading control. Data shown are representative of two biological replicate experiments. (C and E) Rearrangements assays of VHQ52.2.4 (B) or VH7183.4.6 (D) to 5′- or 3′-RSS of DSP2 by deletion or inversion, respectively. ROSA26 was used as the loading control. Data shown are representative of two biological replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that disrupting Eμ/IGCR1 interactions leads to premature rearrangement of VH81X (8) and reduced rearrangement of DFL16.1 (24). Here, we identify additional functional consequences of this interaction that provide mechanistic insights into the two steps of IgH gene assembly. First, DST4.2, a DH gene segment located 52-kb 3′ of VH81X, which recombines rarely on WT IgH alleles, is used efficiently on IGCR1-mutated alleles. However, DMB1 and DFL16.3 gene segments that lie close to DST4.2 do not recombine, presumably because of weak 3′-RSSs. Second, VH81X recombination to unrearranged DH gene segments occurs by both deletion and inversion, using either 5′- or 3′-DH RSSs, respectively. This is in stark contrast to the near universal use of the 3′-DH RSS for DH-to-JH recombination. Third, other VH gene segments, such as VHQ52.2.4 and VH7183.4.6, also recombine by inversion or deletion when provoked to do so by loss of associated CTCF-binding sites that lie 3′ of each gene segment. Thus, Eμ sequestration by IGCR defines DH gene segments that participate in the first step of IgH gene rearrangements and enforces VH recombination by deletion on WT IgH alleles.

Altered Eμ looping makes DST4.2 accessible

Recombination of DST4.2 on IGCR1-mutated alleles can be understood in terms of the altered chromatin configuration of such alleles. In the absence of sequestration by IGCR1 Eμ loops to a CTCF-bound site close to VH81X (Fig. 6, left). DST4.2 is located within this new 150-kb chromatin domain, facilitating its interactions with the JH-associated RC and leading to DST4.2-to-JH recombination. By contrast, DST4.2 is excluded from the 60-kb Eμ-IGCR1 chromatin domain on WT alleles and is therefore not encountered by RC-bound RAG1/2 (Fig. 6, top left). Note that a weak ATAC peak is induced near DST4.2 on IGCR1-deficient alleles. Conversely, the ATAC peak corresponding to a promoter 5′ of DFL16.1 is lost in the absence of Eμ/IGCR1 interaction. One possibility is that the DST4.2 ATAC peak constitutes a latent promoter that is activated by Eμ in the absence of Eμ/IGCR1 interactions. This view is substantiated by the increased interaction of VH-DFL16.1 intervening region with the Eμ-JH region on IGCR1-deleted alleles. Specific transcription factors and associated DNA sequences that contribute to increased recombination potential of DST4.2 on IGCR1-deleted alleles remain to be determined.

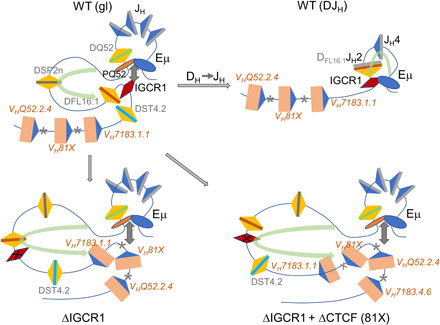

Fig. 6. Distinct rules of engagement during VH and DH gene segment rearrangements.

(Top left) Configuration of WT unrearranged [germline (gl)] IgH alleles extending from the 3′VH genes until Eμ. Gray boxes, JH segments; colored boxes, DH segments; beige boxes, VH segments; blue triangles, 23-RSSs; yellow triangles, 12-RSSs. Previously proposed interactions between regulatory sequences Eμ, IGCR1, and a promoter 5′ of DQ52 (PQ52) are indicated. Asterisks identify CTCF-binding sites associated with proximal VH genes. Light green curved arrow signifies the previously proposed RAG1/2 scanning domain (10). The RAG1/2-rich RC maps closely with PQ52-Eμ region. (Top right) Proposed configuration of DFL16.1JH2 recombined WT IgH alleles. Eμ-IGCR1 interactions remain intact and the size of the RAG1/2 scanning domain is reduced (green arrow). (Bottom left) Configuration of germline IGCR1-mutated IgH alleles showing Eμ looping to the VH81X-associated CTCF-binding site. DST4.2 and VH7183.1.1 are now located within enlarged RAG1/2 scanning domain (green arrow). (Bottom right) Configuration of doubly mutated IgH alleles that lack IGCR1 as well as the VH81X-associated CTCF-binding site (81X) in which Eμ loops to the next available CTCF site located near VHQ52.2.4. DST4.2, VH7183.1.1, and VH81X are located within the further enlarged RAG1/2 scanning domain (green arrow).

Our observation that DST4.2 recombines largely by deletion (using its 3′-RSS) despite having a 5′-RSS of comparable strength shows that, beyond increased chromatin accessibility, its recombination is governed by the same rules that enforce primarily deletional recombination of classical DFL16.1, DSP2, and DQ52 gene segments. Early transfection studies showed that deletional preference of DH recombination extended beyond intrinsic strengths of the 5′- and 3′-RSSs and was attributed at least in part to the relative efficiencies of deletional versus inversional recombination (31). More recently, evidence has accrued in favor of a RAG1/2 tracking model to explain deletional preference of DH gene recombination, whereby RAG1/2 bound to the JH-associated RC scans through the DH region (Fig. 6, green arrows) by a process analogous to loop extrusion that has been proposed to generate CTCF-anchored chromatin loops (2, 10, 21, 23). During such a scan, RAG proteins that have been oriented by JH-RSSs do not efficiently synapse with 5′-DH RSSs, thereby leading to deletional DH recombination. Use of the 3′-RSS of DST4.2 is consistent with this idea.

In a dynamic model, where RAG proteins capture complementary RSSs as the chromatin loop extrudes, the question arises as to what extent DH recombination occurs in the context of a preformed chromatin loop (such as the Eμ/IGCR1 domain on WT alleles). In other words, do loops only determine the number of DH gene segments that interact with or become incorporated into the RC, or do they influence recombinational outcomes in other ways? One observation that supports additional functions for loop anchors is that DFL16.1, the gene segment closest to the loop anchor (IGCR1) on WT alleles, is used more frequently than the more numerous DSP2 gene segments that lie closer to RC in linear DNA (38, 39). We have previously proposed that greater utilization of DFL16.1 might be because of its spatial proximity to the IgH RC in the context of an Eμ-IGCR1 chromatin loop (8, 18). In the absence of Eμ/IGCR1 interaction, DFL16.1 loses its proximity to the RC, resulting in reduced recombination (24). In tying together the two characteristics of DH rearrangements (frequency of use and RSS choice), our working model is that frequency and availability of DH gene segments for rearrangement are regulated by the configuration of the loop, whereas the orientation of recombination is determined by loop dynamics associated with RAG1/2 scanning.

Altered Eμ looping permits VH recombination by inversion

Observation of both deletional and inversional VH recombination demonstrates that both mechanisms can be used by VH gene segments, whereas DH-to-JH recombination proceeds almost exclusively by deleting intervening DNA. Although mutations in IGCR1 are necessary to reveal these differences, we hypothesize that they reflect distinct rules of engagement for DH versus VH gene rearrangements.

First, unlike DH gene segments, location of a VH gene segment within the RAG1/2 scanning domain is apparently insufficient to permit its rearrangement. This can be inferred from very infrequent rearrangement of VH7183.1.1 on IGCR1-deficient alleles. This gene segment lies within the Eμ-VH81X loop (Fig. 6, bottom left), has a functional RSS [(23) and see below], but does not rearrange to either germline or rearranged DH gene segments on IGCR1-deficient IgH alleles. DST4.2 located within the same loop recombines readily by deletion. The simplest interpretation is that RAG proteins remain bound to the RC, so that sufficient RAG1/2 density is not available within the tracking domain to permit synapsis between VH7183.1.1 and DH gene segments. Such a model is consistent with loop extrusion as the mode of RAG1/2 scanning and highlights the importance of a spatially restricted RC for regulated recombination. Because DST4.2 is located closer to the RC compared to VH7183.1.1, it is possible that proximity may also contribute to differences in recombination between these two gene segments. However, the contribution of each mechanism cannot be estimated from available data.

Second, VH gene segments require closely positioned loop anchoring CTCF binding for efficient recombination, whereas DH gene segments do not. For the first three most DH-proximal functional VH gene segments, this has been shown by deleting or mutating associated CTCF-binding sites (23, 24). Conversely, introduction of a functional CTCF-binding site close to VH7183.1.1 sufficed to induce rearrangements of this otherwise recombinationally inert gene (23). Facilitation of VH recombination by closely associated CTCF sites suggests that CTCF may stabilize synapsis between RAG proteins bound to RSSs located in different chromatin domains during this step of IgH gene assembly. In other words, VH and DH gene segments use different mechanisms to find and synapse with complementary RSSs. As described below, our working hypothesis is that VH rearrangements involve diffusion-controlled search for complementary RSS before synapsis.

Third, VH recombination to germline DH gene segments proceeds by both deletional and inversional mechanisms, whereas DH to germline JH rearrangements occur only by deletion. We propose that this dichotomy reflects mechanistic differences by which VH and DH gene segments recombine. One possibility is suggested by the relative positioning of CTCF-binding sites and the VH genes they control. For each of VH81X, VHQ52.2.4, and VH7183.4.6, the activating CTCF-binding site is located 3′ of the gene segment. Because Eμ loops to the nearest CTCF-bound site in the absence of IGCR1, this configuration places the activated VH gene segment outside the Eμ-CTCF chromatin domain (Fig. 6, bottom). On IGCR1-deficient alleles, for example, VH81X would lie outside the Eμ/CTCF domain. We surmise that RAG1/2 scanning by loop extrusion does not “see” VH81X on IGCR1-deficient alleles (and for reasons discussed above “passes by” VH7183.1.1). Mutating the VH81X CTCF site leads to Eμ looping to the VHQ52.2.4-associated CTCF site; again, the recombinationally active VH gene segment lies outside the RAG1/2 scanning domain (Fig. 6, bottom right), and both VH7183.1.1 and VH81X that lie within the domain are passed by. We propose that VH gene segments that lie outside RAG scanning domains seek complementary RSSs by diffusion/collision-controlled mechanisms rather than by directed scanning. During VH-to-DH recombination, this leads to comparable encounter of VH RSSs with 5′- or 3′-DH RSSs and recombination by deletion or inversion, respectively. However, we note that our observations are also consistent with other possibilities such as stalling of RAG 1/2 at CTCF-bound sites near VH genes, providing the opportunity for VH RSSs to synapse with either a 5′- or 3′-DH RSS. Eμ interaction with the VH81X-associated CTCF-binding site on IGCR1-deficient alleles brings VH81X into spatial proximity of the RC but not within the tracking domain, thereby greatly increasing its recombination efficiency. It is plausible that spreading of RAG1/2 into the VH region in the absence of IGCR1 further accentuates recombination potential of the associated VH gene segment (24).

Implications for IgH gene assembly on WT alleles

To what extent do these mechanisms apply to gene assembly on WT IgH alleles? We suggest that VH gene segments find complementary RSSs primarily by diffusion-directed mechanisms even on WT alleles because they lie outside the RC-initiated RAG1/2 scanning domain. At the start of IgH gene assembly, exclusion of VH gene segments from the RAG tracking domain defined by Eμ/IGCR1 interaction ensures that DH recombination occurs first. Because IGCR1 remains intact after DH recombination, continued Eμ sequestration prevents it from looping to highly specific VH gene segments, thereby restricting RAG scanning to the small region between the DJH junction and IGCR1 (Fig. 6, top right). Because all VH gene segments lie outside this domain, they must find DH RSSs by some other mechanisms. We propose that this could be via a diffusion-controlled search aided by locus contraction that brings a prefolded VH region close to the 3′IgH domain. Alternatively, occasional breakdown of the Eμ-IGCR1 loop could lead to generation of specific large loops that include one or more VH gene segments to which RAG1/2 may track from DJH-associated RC. Although VH genes can recombine by either deletion or inversion as revealed in this study, their propensity to do so is neutralized on WT alleles by highest RAG1/2 density at the rearranged DJH junction (40), which targets VH recombination to the 5′-DH RSS. The diffusional mode of RSS recognition by VH gene segments is consistent with our “loops-within-loops” hypothesis for a structured VH locus (25, 41), lack of discrete looping sites observed in 4C (Circular Chromatin Conformation Capture)–seq, as well as the idea of a dynamic VH cloud around the DH/JH region in pro–B cells (42).

We have previously hypothesized that reduced efficiency of VH recombination due to Eμ sequestration on WT alleles may help to enforce allelic exclusion by desynchronizing rearrangements on the two alleles (24). We surmise that a diffusion-controlled search by VH gene segments to synapse with an appropriate RSS may be one mechanism by which recombination efficiency is reduced to enforce recombination asynchrony between two IgH alleles during the second step of IgH gene assembly. Lastly, mechanistic considerations for VH recombination proposed here provide a plausible way to understand inversional V recombination at other antigen receptor loci, such as the Igκ light chain gene locus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary pro–B cell genomic DNA

Bone marrow–derived pro–B cells, marked as B220+IgM−CD43+, were purified from WT 129 or IGCR1−/− mice as previously described (9, 24, 39).

Cell lines

Abelson virus transformed pro–B cell lines CBE−/−(1) and CBE−/−(2) are deficient for RAG2 and homozygous for IgH alleles in which both CBEs within IGCR1 are mutated (8). RAG2-deficient pro–B cells contain WT IgH alleles (6). CBE−/−(1)/C1−/−#1, CBE−/−(1)/C1−/−#2, and CBE−/−(1)/C1−/-C2−/−, derived from pro–B cell lines CBE−/−(1), were generated with CRISPR-Cas9 system, as previously described (24). D345 is an Abelson virus transformed pro–B cell line with WT IgH alleles that expresses a catalytically inactive RAG1 (19). D345/IGCR1−/−(1) and D345/IGCR1−/−(2) were generated from D345 by CRISPR-Cas9–mediated deletion of IGCR1, as previously described (24). Cells were cultured in RPMI medium (#11875-119, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; #SH30070.03, Hyclone) and 56 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (#M3148, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Capture Hi-C

Hi-C was performed using the Arima Hi-C Kit (catalog no. A510008, Arima Genomics Inc.). Briefly, 106 cells were cross-linked in 2% formaldehyde (final concentration). Fixed cells were lysed, digested with two restriction enzymes provided in the Arima Kit and then ligated and decross-linked. Religated fragments were sheared using a Covaris sonicator. DNA fragments of 200 to 600 bp were selected using the SPRI beads (catalog no. B23318, Beckman Coulter Inc.) and then enriched using Enrichment Beads provided in Arima. Enriched DNA fragments were processed into Illumina-compatible sequencing libraries with TruSeq unique dual index adapters (catalog no. 20020590) using KAPA HyperPrep reagents (catalog no. KK8500, Roche Molecular Systems Inc.).

For IgH locus enrichment, SureSelect Target Enrichment probes with 2× tiling density were designed over the genomic interval (mm10, chr12: 113,201,001 to 116,030,000) using the SureDesign tool and manufactured by Agilent (Agilent Technologies Inc.). Hi-C libraries were hybridized to probes as specified by the manufacture, and eluted libraries were sequenced using Illumina NextSeq sequencer to generate paired-end 150-bp reads.

Capture Hi-C data analysis

The mouse reference genome mm10 reference sequences in FASTA files were downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC). The raw capture Hi-C data in FASTQ files were processed by HiCUP (version 0.7.2) (43) with the settings of “Arima” (genome digest file generated with hiccup_digester --arima) to mm10, with mapping tool Bowtie2 (version 2.3.5) (44). The processed reads in BAM files from HiCUP were further processed to HIC file through Juicer (version 1.6.0) (45) for visualization of Juicebox (46) for raw interaction data, with the contact matrix resolution settings of 200, 1000, 5000, 25,000, and 50,000. Normalized contact frequencies were obtained by further processing BAM files from HiCUP into frequency contact matrices with resolution bin size of 1 kb. Contact frequencies were normalized to total mapped reads to yield reads per million mapped reads for visualization and comparison between WT and mutated alleles. Heatmaps were generated through seaborn package (https://seaborn.pydata.org) heatmap function.

CTCF ChIP-seq

CTCF chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data were extracted from (47) [Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), GSM987805]. Direction of CTCF was analyzed with software designed by Yan Cui at University of Tennessee Health Science Center (http://insulatordb.uthsc.edu/) and determined by using higher score and better match as criteria.

Assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing

ATAC was performed as previously described (48, 49). Briefly, 200,000 RAG2-deficient pro–B cells with WT or IGCR1-mutated [CBE−/−(1) and CBE−/−(2)] IgH alleles were collected by centrifugation and washed once with 100-μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell pellets were then resuspended in 50-μl lysis buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40 (Igepal CA-630)] and immediately centrifuged at 500g for 10 min at 4°C. Nuclei-containing pellets were resuspended in 50-μl transposition buffer [25-μl 2× tagment DNA (TD) buffer, 22.5-μl dH2O, 2.5-μl Illumina Tn5 transposase] and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Transposed DNA was purified with DNA Clean and Concentrator columns (ZymoResearch). Library fragments were amplified with 1× NEBNext PCR Master Mix and custom Nextera PCR primers 1 to 6. The number of cycles was 11. Libraries were purified with DNA Clean and Concentrator columns. Libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 system as single reads. The single-end ATAC-seq reads were first trimmed to remove adaptor content using trimmomatic (50) and aligned to mouse genome mm9 using Bowtie2 (44). Then, reads with mapping quality score < 10 were filtered out using SAMtools (51), and PCR duplicates were removed using Picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Chromatin accessible sites (i.e., peaks) were identified using MACS (model-based analysis of ChIP-seq) (52) with a q value of <0.01 as cutoff. To visualize the ATAC-seq signals, BEDTools (53) and UCSC Genome Browser Utilities (54) were used to transform the BAM files into bigWig files. The signals were normalized by divided by the total number of reads in each sample and scaled by a constant N (N = 100,000,000).

To perform differential analysis of chromatin accessibility between cell types, peaks from all cell types (each cell type has two replicate samples) were first merged to form a union set of chromatin accessible sites. Then, for a pair of cell types in question [e.g., WT versus CBE−/−(1)], the number of reads fall in each chromatin accessible site was counted. The count data were normalized by divided by the total number of reads in each sample and scaled by a constant N (N = 100,000,000). The normalized data were further log2-transformed after adding a pseudo count of one. Differential analysis was then performed using limma (55) on the basis of moderated t tests. To adjust for multiple testing, P values were adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to obtain false discovery rate.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT)–PCR were carried out as previously described (24). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (#74134, Qiagen). RNA (1 μg) was used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) with SuperScript III (#18080-051, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Approximately, 1 of 20 of the reverse transcription–generated cDNA was analyzed with iTaq Universal SYBR (#1725125, Bio-Rad). γ-Actin mRNA was used as normalization control. Primers that were used for PCR are provided in table S4. Two independent experiments were carried out. Data are presented first according to the formula relative level = 2(CT(γ-actin) − CT(target)), followed by normalization to levels in control cells (y axis).

Rag2 transduction

Lentiviral particles expressing Rag2 were generated as described (24) by transiently transfecting 293T cells with lentiviral plasmid containing Rag2 and puromycin resistance DNA fragment (pHIV-RAG2-IRES-puro) along with helper plasmids pMD2.G (#12259, Addgene) and psPAX2 (#12260, Addgene) using BioT reagent (#B01-01, Bioland Scientific LLC). Plasmids and BioT were used in the following ratio: pHIV-RAG2-IRES-puro (5 μg), pMD2.G (2.5 μg), psPAX2 (2.5 μg), and BioT (15 μl). The lentivirus containing the supernatant was collected at 72 hours after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 hours at 25,000 rpm and 20°C over a 20% sucrose cushion. The supernatant was removed after ultracentrifugation, and 200-μl PBS was added to the tube. Fresh virus was prepared for all infection. All procedures involving lentiviruses were performed under BSL2 (biosafety level 2) conditions.

DJH/VDH recombination assays

DJH/VDH recombination assays were carried out as previously described (24). Genomic DNA was purified from sorted bone marrow pro–B cells (B220+IgM−CD43+) from WT or IGCR1−/− mice. Fivefold serial dilutions of genomic DNA (200, 40, and 8 ng) were used to perform PCR to analyze DJH rearrangements. Primers used in this assay are listed in table S4. Primers flanking the ROSA26 gene were used as a loading control under the same conditions. GeneRuler 100 bp Plus (#SM0324, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to confirm sizes of PCR products.

RAG2-deficient pro–B cell lines, CBE−/−(1), CBE−/−(2), WT, CBE−/−(1)/C1−/−#1, CBE−/−(1)/C1−/−#2, and CBE−/−(1)/C1−/-C2−/−, were infected with RAG2-expressing lentivirus and cultured in complete medium with puromycin (2 μg/ml; #A1113803, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 14 days of selection with puromycin, cells were harvested. Genomic DNA was collected with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (#69506, Qiagen), and the DNA was used to analyze DJH/VDJH rearrangements with HotStarTaq DNA Polymerase (#203205, Qiagen) as described as above. The purified PCR product of DJH or VDH was cloned into pGEM-T vector (#A3600, Promega Corporation), transformed into MAX Efficiency DH5α competent cells (#18258-012, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and sequenced. Sequenced results were aligned to VH, DH and JH in Mus musculus strain 129S1/SvImJ.

Recombination efficiency assay

293T cells were cultured overnight to 70% confluence in a 60-mm culture dish with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium with 10% FBS and 56 μM 2-mercaptoethanol at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cultured 293T cells were cotransfected with recombination reporter plasmid with or without RAG1/2-expressing vectors using BioT reagent (#B01-01, Bioland). Plasmids and BioT were used in the following ratio: recombination reporter (1 μg), RAG1 (1 μg), RAG2 (1 μg), and BioT (4.5 μl). Twenty-four hours later, supernatants were gently removed, and DMEM medium with 2.5% FBS and 56 μM 2-mercaptoethanol was gently added. Medium replacement was gently carried out to avoid floating 293T cells. Twenty-four hours later, 293T cells were harvested and labeled with Thy1.2 antibodies (#105317, BioLegend) and prepared for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Thy1.2-positive cells were gated and analyzed for GFP intensity. Recombination efficiency was calculated as the proportion of GFP+ cells within Thy1.2+ population. Control 1 (nonfunctional 12-RSS) was used as a normalization. Recombination efficiency of control 1 was set as 1%. Three independent experiments were carried out.

Recombination efficiency of recombination reporters in pre–B cell line was carried out as previously described (29, 30). Twenty-four T cells were cotransfected with recombination reporter (control 1, DMB1 3′-RSS, DST4.2 5′-RSS, DST4.2 3′-RSS, DFL16.1 5′-RSS, and DFL16.1 3′-RSS) and packaging plasmid pCL-Eco (#12371, Addgene), along with transfection reagent BioT. Ratio is recombination reporter (5 μg), pCL-Eco (5 μg), and BioT (15 μl). The supernatant was collected after 2 days and concentrated for the collection of retrovirus. Pre–B cell lines were infected with these six different concentrated retrovirus. Twenty-four hours later, infected pre–B cell lines were treated with 3.0 μM STI571 (#S2475, Selleck Chemicals). Cells were collected and prepared for FACS analysis as mentioned above after 2 days treatment with STI571. Recombination efficiency was calculated as the proportion of GFP+ cells within Thy1.2+ population. Control 1 was used as a normalization. Recombination efficiency of control 1 was set as 1%. Two independent experiments were carried out. Sequence and result of different 12-RSS are listed in table S1.

Deep sequencing for recombination

VDH or DJH deep sequencing assays were performed as previously described (33). Genomic DNA was extracted as mentioned above. RAG2-deficient pro–B cell lines, WT, CBE−/−(1) and CBE−/−(2), were infected with RAG2-expressing lentivirus, and cultured in complete medium with puromycin (2 μg/ml). After 14 days selection with puromycin, cells were harvested, and genomic DNA was collected with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (#69506, Qiagen). Briefly, 80 ng of genomic DNA from each sample was sonicated to an average size of 750 bp. Sonicated DNA was hybridized with Bio-DQ52 or Bio-DSP2 primer, purified with Dynabeads C1 streptavidin beads (#65002, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and used for library generation as described (39). Restriction enzyme Sac 1–HF [R3156S, New England Biolabs (NEB)] and Bse YI (R0635S, NEB) were used to digest germline DNA with DQ52 and DSP2 as bait, respectively. Paired-end reads (2 × 250) were generated by Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer. Samples were separated using barcodes present in read 1 (tables S2 and S3). Adapters, if present, were removed by cutadapt, and bad quality bases (<Q33) were trimmed from read 2 keeping a minimum length of 80 bases. The reads (read 2 only) were aligned to 1500 bp (for VH81X) and 2767 bp (for JHs) using bowtie2. Reads which aligned to VH81X (Inv) or JHs (Del) with an alignment quality > 20 were counted.

Amplification efficiency analysis

Sense and antisense oligo nucleotides (1 μM) representing deleted or inverted recombination products were annealed in 1× NEB CutSmart buffer (#B7204S, New England Biolabs) for 5 min at 95°C in heat block, followed by cooling down to room temperature after turning off the heat block. Annealed oligoes (1 μM) were then serial diluted to 1 × 10−4 nM (100%), 1 × 10−5 nM (10%), and 1 × 10−6 nM (1%). No oligo was used as the control. Quantitative PCR was carried out for amplification efficiency analysis using 200 ng of genomic DNA from RAG2-deficient cell line, 2.6 μl of serially diluted oligoes, 0.25 μl of forward and reverse primers at a stock concentration of 20 μM, 10 μl of iTaq Universal SYBR (#1725125, Bio-Rad), and up to 20 μl of water. Sequence of oligoes is listed in table S4. Recombination efficiency was calculated according to the formula relative level = 2(CT(Inversion, +100% oligo) − CT(target)). Three independent experiments were carried out.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis (adjusted P value) with R statistical software (www.r-project.org/) was carried out for ATAC-seq peaks in Fig. 1C. Detailed statistical analysis result for ATAC-seq peaks in Fig. 1C is listed in fig. S1C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. W. Alt, S. G. Lin, and S. Jain (Harvard Medical School) for providing IGCR1-mutated cell lines and genomic DNA from sorted bone marrow pro–B cells from IGCR1-deleted mice. We also thank F. W. Alt and D. G. Schatz (Yale University) for critical comments on our manuscript. Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (to R.S.), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (to K.Z.), the 4DN Transformative Collaborative Project Award (A-0066) (to K.Z.), NIH R01 grant HG009518 (to H.J.), and NIH R01 grants AI079002 and GM111384 (to M.L.A.). Author contributions: X.Q. and R.S. conceived and designed the research. X.Q. performed most of the experiments. F.M. performed the capture Hi-C experiment. M.Z. performed the ATAC-seq experiment. F.M., L.S., A.L., A.D., A.S., and F.Z.B. generated plasmids and sequenced VD recombination junctions. X.Q., F.M., M.Z., Y.C., S.D., W.H.W., K.G.B., W.Z., H.J., K.Z., and M.L.A. analyzed the data. X.Q., F.M., and R.S. interpreted the data and results and wrote the manuscript. All authors provided input and approved the final manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Raw and processed capture Hi-C, ATAC-seq, and VDJ deep sequencing data can be accessed from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GEO database under accession numbers GSE145472, GSE133185, and GSE135763. Raw image data were deposited into DRYAD (https://datadryad.org/stash/share/pLwyVhk4JJNzCMJq4k4Xp8yQYGIPMSKICcqwKKSkMag). All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/33/eaaz8850/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Teng G., Schatz D. G., Regulation and evolution of the RAG recombinase. Adv. Immunol. 128, 1–39 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin S. G., Ba Z., Alt F. W., Zhang Y., RAG chromatin scanning during V(D)J recombination and chromatin loop extrusion are related processes. Adv. Immunol. 139, 93–135 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumari G., Sen R., Chromatin interactions in the control of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene assembly. Adv. Immunol. 128, 41–92 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afshar R., Pierce S., Bolland D. J., Corcoran A., Oltz E. M., Regulation of IgH gene assembly: Role of the intronic enhancer and 5′DQ52 region in targeting DHJH recombination. J. Immunol. 176, 2439–2447 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty T., Chowdhury D., Keyes A., Jani A., Subrahmanyam R., Ivanova I., Sen R., Repeat organization and epigenetic regulation of the DH-Cμ domain of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene locus. Mol. Cell 27, 842–850 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty T., Perlot T., Subrahmanyam R., Jani A., Goff P. H., Zhang Y., Ivanova I., Alt F. W., Sen R., A 220-nucleotide deletion of the intronic enhancer reveals an epigenetic hierarchy in immunoglobulin heavy chain locus activation. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1019–1027 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlot T., Alt F. W., Bassing C. H., Suh H., Pinaud E., Elucidation of IgH intronic enhancer functions via germ-line deletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14362–14367 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C., Yoon H. S., Franklin A., Jain S., Ebert A., Cheng H.-L., Hansen E., Despo O., Bossen C., Vettermann C., Bates J. G., Richards N., Myers D., Patel H., Gallagher M., Schlissel M. S., Murre C., Busslinger M., Giallourakis C. C., Alt F. W., CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature 477, 424–430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin S. G., Guo C., Su A., Zhang Y., Alt F. W., CTCF-binding elements 1 and 2 in the Igh intergenic control region cooperatively regulate V(D)J recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 1815–1820 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J., Zhang L., Zhao R. L. F., Du Z., Meyers R. M., Meng F.-l., Schatz D. G., Alt F. W., Chromosomal loop domains direct the recombination of antigen receptor genes. Cell 163, 947–959 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L., Carico Z., Shih H.-Y., Krangel M. S., A discrete chromatin loop in the mouse Tcra-Tcrd locus shapes the TCRδ and TCRα repertoires. Nat. Immunol. 16, 1085–1093 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L., Zhao L., Alt F. W., Krangel M. S., An ectopic CTCF binding element inhibits Tcrd rearrangement by limiting contact between Vδ and Dδ gene segments. J. Immunol. 197, 3188–3197 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majumder K., Koues O. I., Chan E. A. W., Kyle K. E., Horowitz J. E., Yang-Iott K., Bassing C. H., Taniuchi I., Krangel M. S., Oltz E. M., Lineage-specific compaction of Tcrb requires a chromatin barrier to protect the function of a long-range tethering element. J. Exp. Med. 212, 107–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao L., Frock R. L., Du Z., Hu J., Chen L., Krangel M. S., Alt F. W., Orientation-specific RAG activity in chromosomal loop domains contributes to Tcrd V(D)J recombination during T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 213, 1921–1936 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S., Luperchio T. R., Wong X., Doan E. B., Byrd A. T., Roy Choudhury K., Reddy K. L., Krangel M. S., a lamina-associated domain border governs nuclear lamina interactions, transcription, and recombination of the Tcrb locus. Cell Rep. 25, 1729–1740.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang Y., Park S.-K., Garrard W. T., A major deletion in the Vκ–Jκ intervening region results in hyperelevated transcription of proximal Vκ genes and a severely restricted repertoire. J. Immunol. 193, 3746–3754 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro de Almeida C., Stadhouders R., de Bruijn M. J. W., Bergen I. M., Thongjuea S., Lenhard B., van IJcken W., Grosveld F., Galjart N., Soler E., Hendriks R. W., The DNA-binding protein CTCF limits proximal Vκ recombination and restricts κ enhancer interactions to the immunoglobulin κ light chain locus. Immunity 35, 501–513 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner S. C., Verma-Gaur J., Wong T. P., Bossen C., Iverson G. M., Torkamani A., Vettermann C., Lin Y. C., Ju Z., Schulz D., Murre C. S., Birshtein B. K., Schork N. J., Schlissel M. S., Riblet R., Murre C., Feeney A. J., CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9566–9571 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji Y., Resch W., Corbett E., Yamane A., Casellas R., Schatz D. G., The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell 141, 419–431 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo C., Gerasimova T., Hao H., Ivanova I., Chakraborty T., Selimyan R., Oltz E. M., Sen R., Two forms of loops generate the chromatin conformation of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene locus. Cell 147, 332–343 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., Zhang X., Ba Z., Liang Z., Dring E. W., Hu H., Lou J., Kyritsis N., Zurita J., Shamim M. S., Presser Aiden A., Lieberman Aiden E., Alt F. W., The fundamental role of chromatin loop extrusion in physiological V(D)J recombination. Nature 573, 600–604 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates J. G., Cado D., Nolla H., Schlissel M. S., Chromosomal position of a VH gene segment determines its activation and inactivation as a substrate for V(D)J recombination. J. Exp. Med. 204, 3247–3256 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain S., Ba Z., Zhang Y., Dai H.-Q., Alt F. W., CTCF-binding elements mediate accessibility of RAG substrates during chromatin scanning. Cell 174, 102–116.e14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu X., Kumari G., Gerasimova T., Du H., Labaran L., Singh A., De S., Wood W. H. III, Becker K. G., Zhou W., Ji H., Sen R., Sequential enhancer sequestration dysregulates recombination center formation at the IgH locus. Mol. Cell 70, 21–33.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerasimova T., Guo C., Ghosh A., Qiu X., Montefiori L., Verma-Gaur J., Choi N. M., Feeney A. J., Sen R., A structural hierarchy mediated by multiple nuclear factors establishes IgH locus conformation. Genes Dev. 29, 1683–1695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Featherstone K., Wood A. L., Bowen A. J., Corcoran A. E., The mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain V-D intergenic sequence contains insulators that may regulate ordered V(D)J recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9327–9338 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolland D. J., Koohy H., Wood A. L., Matheson L. S., Krueger F., Stubbington M. J. T., Baizan-Edge A., Chovanec P., Stubbs B. A., Tabbada K., Andrews S. R., Spivakov M., Corcoran A. E., Two mutually exclusive local chromatin states drive efficient V(D)J recombination. Cell Rep. 15, 2475–2487 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sollbach A. E., Wu G. E., Inversions produced during V(D)J rearrangement at IgH, the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 671–681 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bredemeyer A. L., Sharma G. G., Huang C.-Y., Helmink B. A., Walker L. M., Khor K. C., Nuskey B., Sullivan K. E., Pandita T. K., Bassing C. H., Sleckman B. P., ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature 442, 466–470 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gapud E. J., Lee B.-S., Mahowald G. K., Bassing C. H., Sleckman B. P., Repair of chromosomal RAG-mediated DNA breaks by mutant RAG proteins lacking phosphatidylinositol 3-like kinase consensus phosphorylation sites. J. Immunol. 187, 1826–1834 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gauss G. H., Lieber M. R., The basis for the mechanistic bias for deletional over inversional V(D)J recombination. Genes Dev. 6, 1553–1561 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alt F. W., Baltimore D., Joining of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene segments: Implications from a chromosome with evidence of three D-JH fusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 4118–4122 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J., Meyers R. M., Dong J., Panchakshari R. A., Alt F. W., Frock R. L., Detecting DNA double-stranded breaks in mammalian genomes by linear amplification–mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 11, 853–871 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall A. J., Wu G. E., Paige G. J., Frequency of VH81x usage during B cell development: Initial decline in usage is independent of Ig heavy chain cell surface expression. J. Immunol. 156, 2077–2084 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawler A. M., Lin P. S., Gearhart P. J., Adult B-cell repertoire is biased toward two heavy-chain variable-region genes that rearrange frequently in fetal pre-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 2454–2458 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perlmutter R. M., Kearney J. F., Chang S. P., Hood L. E., Developmentally controlled expression of immunoglobulin VH genes. Science 227, 1597–1601 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yancopoulos G. D., Desiderio S. V., Paskind M., Kearney J. F., Baltimore D., Alt F. W., Preferential utilization of the most JH-proximal VH gene segments in pre-B-cell lines. Nature 311, 727–733 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi N. M., Loguercio S., Verma-Gaur J., Degner S. C., Torkamani A., Su A. I., Oltz E. M., Artyomov M., Feeney A. J., Deep sequencing of the murine IgH repertoire reveals complex regulation of nonrandom V gene rearrangement frequencies. J. Immunol. 191, 2393–2402 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin S. G., Ba Z., Du Z., Zhang Y., Hu J., Alt F. W., Highly sensitive and unbiased approach for elucidating antibody repertoires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 7846–7851 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subrahmanyam R., Du H., Ivanova I., Chakraborty T., Ji Y., Zhang Y., Alt F. W., Schatz D. G., Sen R., Localized epigenetic changes induced by DH recombination restricts recombinase to DJH junctions. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1205–1212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montefiori L., Wuerffel R., Roqueiro D., Lajoie B., Guo C., Gerasimova T., De S., Wood W., Becker K. G., Dekker J., Liang J., Sen R., Kenter A. L., Extremely long-range chromatin loops link topological domains to facilitate a diverse antibody repertoire. Cell Rep. 14, 896–906 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucas J. S., Zhang Y., Dudko O. K., Murre C., 3D trajectories adopted by coding and regulatory DNA elements: First-passage times for genomic interactions. Cell 158, 339–352 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wingett S., Ewels P., Furlan-Magaril M., Nagano T., Schoenfelder S., Fraser P., Andrews S., HiCUP: Pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Res. 4, 1310 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langmead B., Salzberg S. L., Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durand N. C., Shamim M. S., Machol I., Rao S. S. P., Huntley M. H., Lander E. S., Aiden E. L., Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durand N. C., Robinson J. T., Shamim M. S., Machol I., Mesirov J. P., Lander E. S., Aiden E. L., Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y. C., Benner C., Mansson R., Heinz S., Miyazaki K., Miyazaki M., Chandra V., Bossen C., Glass C. K., Murre C., Global changes in the nuclear positioning of genes and intra- and interdomain genomic interactions that orchestrate B cell fate. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1196–1204 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buenrostro J. D., Giresi P. G., Zaba L. C., Chang H. Y., Greenleaf W. J., Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bossen C., Murre C. S., Chang A. N., Mansson R., Rodewald H.-R., Murre C., The chromatin remodeler Brg1 activates enhancer repertoires to establish B cell identity and modulate cell growth. Nat. Immunol. 16, 775–784 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B., Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup , The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C. A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D. S., Bernstein B. E., Nussbaum C., Myers R. M., Brown M., Li W., Liu X. S., Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M., BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kent W. J., Zweig A. S., Barber G., Hinrichs A. S., Karolchik D., BigWig and BigBed: Enabling browsing of large distributed datasets. Bioinformatics 26, 2204–2207 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritchie M. E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C. W., Shi W., Smyth G. K., Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/33/eaaz8850/DC1