Abstract

DNA analysis based on the observation of single DNA molecules has been a key technology in molecular biology. Several techniques for manipulating single DNA molecules have been proposed for this purpose; however, these techniques have limits on the manipulatable DNA. To overcome this, we demonstrate a method of DNA manipulation using microstructures captured by optical tweezers that allow the manipulation of a chromosomal DNA molecule. For proper DNA handling, we developed microstructures analogous to chopsticks to capture and elongate single DNA molecules under an optical microscope. Two microstructures (i.e., microchopsticks) were captured by two focused laser beams to pinch a single yeast chromosomal DNA molecule between them and thereby manipulate it. The experiments demonstrated successful DNA manipulation and revealed that the size and geometry of the microchopsticks are important factors for effective DNA handling. This technique allows a high degree of freedom in handling single DNA molecules, potentially leading to applications in the study of chromosomal DNA.

INTRODUCTION

Gene analysis based on the observation of single DNA molecules has been a key technology in molecular biology. A number of techniques have been developed, including extended fiber FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization),1–3 DNA-protein interaction assays,4–6 and DNA sequencing.7–9 The standard techniques for analyzing chromosomal DNA molecules are bulk-based methods that fragment DNA molecules into short pieces.10 This results in loss of positional information along the DNA strand and information on the three-dimensional conformation of each chromosomal DNA molecule. Consequently, the development of the manipulation of intact single chromosomal DNA molecules should lead to novel chromosomal analysis; however, it remains a technical challenge.

Several techniques for manipulating single DNA molecules have been proposed, including those based on optical tweezers,11–13 magnetic tweezers,14,15 and nanotweezers.16,17 Optical tweezers and magnetic tweezers use microspheres where DNA molecules are immobilized. A single DNA molecule is manipulated through a microsphere, which allows manipulation in a microfluidic device having microchannels surrounded by solid walls. Both techniques, however, involve a process for attaching DNA molecules to microspheres that inevitably limit the manipulatable DNA length to less than 100 kbp due to shear force in liquid handling. Once a DNA molecule is immobilized to a microsphere, it cannot be released, hindering further manipulation. Nanotweezers also capture and elongate DNA molecules, although capturing only the targeted DNA molecule remains a technical challenge. In addition, the tweezers need physical access to DNA molecules externally, preventing integration with a microfluidic device. To overcome this, we previously proposed a DNA manipulation technique18,19 using electro-osmotic flow (EOF) and microstructures captured by optical tweezers that allow the manipulation of a chromosomal DNA molecule. We have developed a microhook to pick up a DNA molecule and a microbobbin to wind a DNA molecule. However, this technique still limits the mode of DNA manipulation, particularly in the capture and elongation of a targeted random-coiled DNA molecule for high-resolution DNA imaging. Both structures are limited in use for extended DNA molecules. In addition, a microhook cannot be released once it hooks a DNA molecule, as in the case of a DNA molecule immobilized on a microsphere.

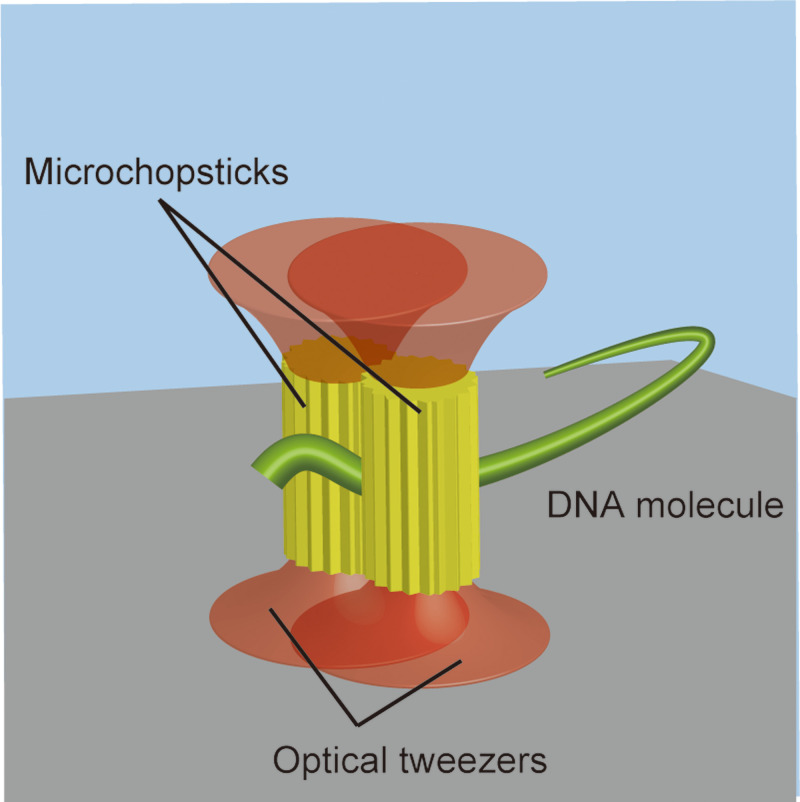

To improve the DNA handling, we developed microstructures to capture and manipulate each DNA molecule in a method analogous to handling with chopsticks (Fig. 1) and demonstrated chromosomal DNA manipulation using them. Two microstructures (i.e., microchopsticks) were captured by two focused laser beams and manipulated to pinch a single DNA molecule between them and thereby manipulate it. This configuration allows the capture of a targeted DNA molecule with random-coiled conformation as well as the release of the molecule, like manipulation of a fiber with chopsticks. In addition, microchopsticks are easily introduced into microchannels and manipulated there, enabling us to take advantage of microfluidic devices. Thus, this technique allows a high degree of freedom in the handling of single DNA molecules, potentially leading to applications in research on the interaction between single chromosomal DNA molecules and proteins and the analysis of chromosomal structure and dynamics20,21 through integration with microfluidic devices.

FIG. 1.

On-site DNA manipulation using two microstructures driven by dual-beam optical tweezers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Optical tweezers setup

We constructed a dual-beam optical tweezers setup with two trap points in the focal plane of an optical microscope.18 An ytterbium fiber laser (wavelength: 1064 nm CW, IGP Photonics) was introduced into an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX-71, Olympus). The laser beam was divided into two paths through a wave plate and split by a beam splitter. Each laser beam was reflected by mirrors and coaxially combined by a beam combiner. The trapping points were moved in the focal plane of the microscope by adjusting the angle of the mirrors. The two laser beams were reflected by the dichroic mirror of the microscope and were introduced into an oil immersion objective lens (100×, N.A. = 1.40, Olympus) to focus on the observation plane. Fluorescence images were obtained using an EM-CCD camera (ImagEM, Hamamatsu Photonics).

DNA sample

Yeast chromosomal DNA molecules (CHEF DNA Size standard S. pombe, Bio-Red) were used as test samples. DNA molecules were embedded in a gel block and incubated at 70 °C before being extracted in aqueous solution. DNA molecules were stained with 1 μM YO-PRO-1 (Molecular Probes)/1.4 mM dithiothreitol (TAKARA), 0.05% Tween 20. Next, 8 μl of the suspension containing the microstructures was dispensed onto the DNA sample solution on a glass substrate, making 10 μl in total. The samples were placed on a motorized microscope stage.

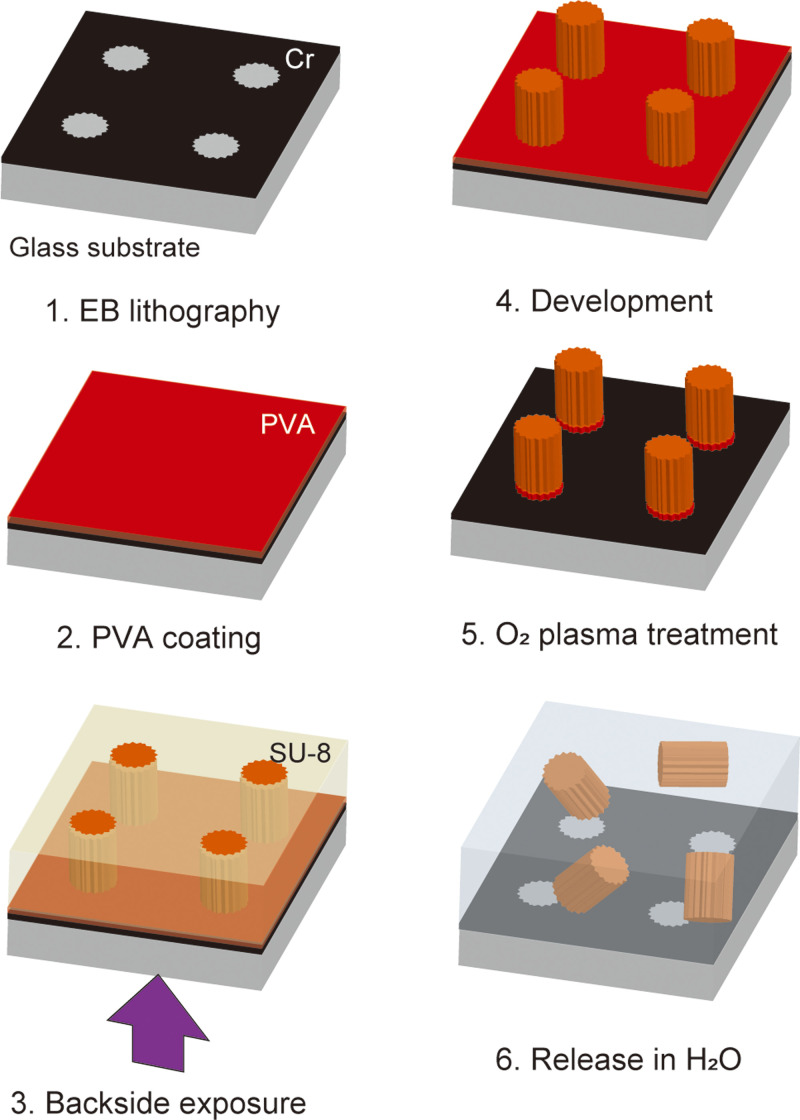

Fabrication of microchopsticks

Microchopsticks were fabricated using a combination of electron beam (EB) lithography and UV lithography (Fig. 2). Chromium was patterned on a glass substrate using EB lithography. This was then coated with a 5% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution (P8136, Sigma-Aldrich) as a sacrificial layer. After that, a coat of SU-8 was applied. The substrates were exposed to UV light through the Cr pattern and developed. The PVA was then removed by O2 plasma dry etching, and 240 000 microstructures were released into de-ionized water.

FIG. 2.

Fabrication process of microstructures.

To evaluate the effect of microstructure size on DNA handling, we fabricated microstructures of two sizes, blockA and blockB, both with a rectangular parallelepiped shape. The dimensions of the small block (blockA) were 5.0 × 2.5 μm2 and those of the large block (blockB) were 10.0 × 5.0 μm2. The structures had the same thickness, which was determined by the thickness of the SU-8 coating. We determined the size suitable for DNA manipulation, based on the performance of the blocks in DNA capture, and designed other microstructures of a similar size but with different geometries.

Evaluation of microchopsticks

We evaluated the relationship between the laser power and trapping force using each microstructure (blockA and blockB). The viscous drag force exerted on a microstructure moving in an aqueous solution is balanced by the optical trapping force. Hence, the maximum speed of microstructures moved by optical tweezers gives the maximum trapping force.18 In the low Reynolds number regime (Re < 1), the viscous drag, F, is calculated as

| (1) |

where μ, , and v are viscosity, the radius of sphere with the same volume as the structure, and the velocity of the structure, respectively.22 K is a shape factor of parallelepipeds, calculated from the equation

| (2) |

where is the radius of a circle of an area equal to the projected area of the object perpendicular to the direction of the movement. shows the sphericity of the object, defined as

| (3) |

where and are the area of a sphere of the same volume as the object and the area of the object itself, respectively. The optical trapping force was estimated from these equations using the maximum speed of a moving microstructure.

We evaluated the efficiency of DNA capture with each pair of microstructures (blockA and blockB). Two microstructures were trapped by two focused laser beams and handled like chopsticks to pinch a DNA molecule between them, and the number of successful trials of DNA capture were compared to the number of failed trials to obtain the DNA capture rate. To evaluate the effect of microstructure geometry on DNA manipulation, DNA molecules were captured between microstructures with four different geometries and translocated by moving the x–y microscope stage at a speed of 50 μm/s. We evaluated to what extent the DNA became elongated before escaping from the space between the microchopsticks.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Microchopstick dimensions

The block structures were successfully fabricated and collected in aqueous solution (Fig. 3). The fabrication is a batch process based on a single operation of UV lithography using an EB mask. Thus, it is suitable for high-throughput fabrication. This feature is key for its use in optical manipulation, because a large number of microstructures allow us to find them easily in the small observation field of a microscope, leading to efficient operation. In addition, the photoresist is directly applied onto an EB mask and exposed from the backside, improving the resolution of the structures to submicron dimensions.

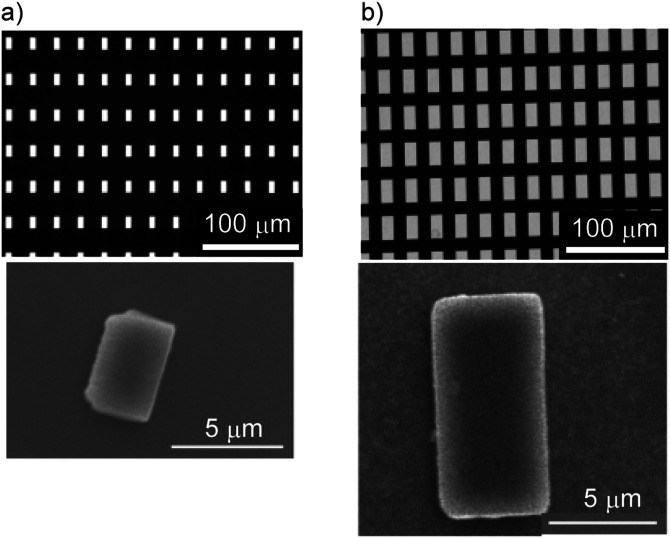

FIG. 3.

Microstructures for evaluating the size dependence of DNA capture. Top: Mask pattern. Bottom: SU-8 structures released from the mask substrate. (a) BlockA. (b) BlockB.

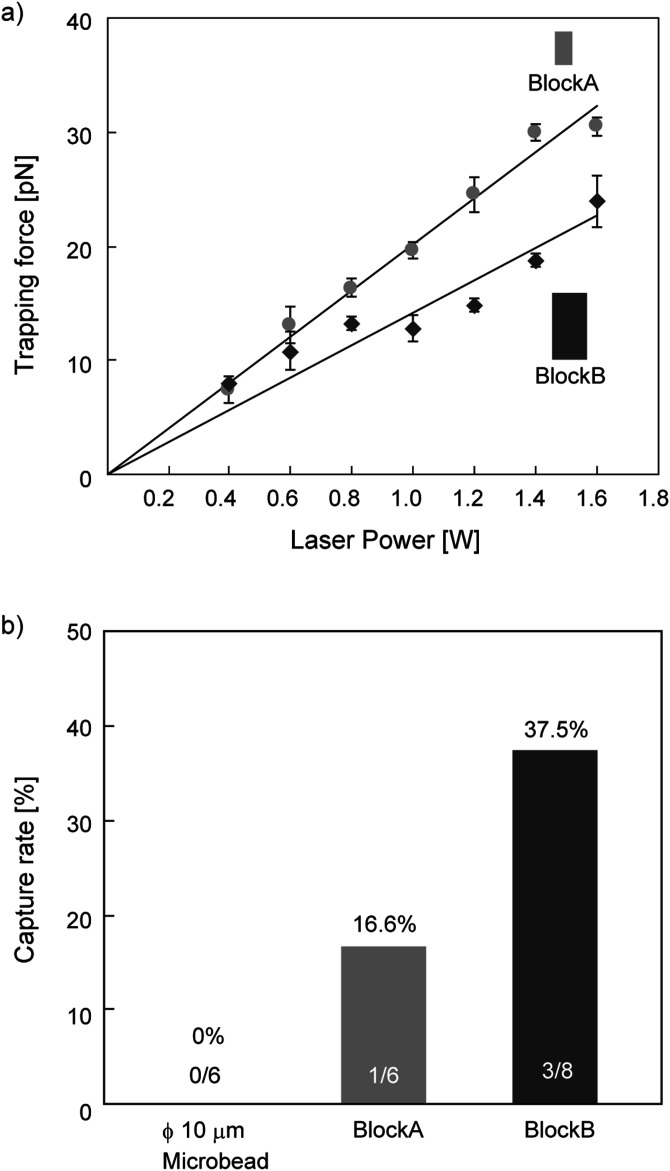

The measured dimensions of blockA were 5.1 × 2.9 μm2 and those of block B were 9.9 × 5.0 μm2; both had a thickness of 3.7 μm. We then trapped a microstructure using optical tweezers and measured the trapping force in the range from 0.4 to 1.6 W in laser output power [Fig. 4(a)]. The blocks were trapped with their longest axis aligned with the direction of laser propagation, which defined their orientations as reported in the optical trapping of elongated objects.19,23 The results show a linear increase in the trapping force, where the maximum force was 30.5 pN for blockA and 24.0 pN for blockB in our setup. This suggests that the small block (blockA) allowed translocation faster than the large block (blockB). The force range was less than 40 pN, whereas DNA breakage is likely to occur at a force in the range of 100–300 pN.24 This indicates that the trapping force is adequate for manipulating a DNA molecule without breaking its strands.

FIG. 4.

Evaluation of the size of rectangular microstructures (blockA and blockB). (a) Optical trapping force of microstructures. Error bars show SD. (b) Capture rate of single DNA molecules using microstructures. The fractions indicate (the number of trials with successful DNA capture)/(total number of trials).

We pinched a DNA molecule using two microstructures driven by dual-beam optical tweezers and evaluated the DNA capture rate [Fig. 4(b)]. We counted a single operation to sandwich a DNA molecule between two microstructures as one trial. When two microspheres of 10 μm diameter were used for a control experiment, a DNA molecule escaped from the space between the microspheres and was not captured between them. In contrast, blockA and blockB were able to capture DNA molecules with a success rate of 16.6% and 37.5%, respectively. The rate is still lower than 50%, although repeated trials with a targeted DNA molecule bring feasible capture for further DNA manipulation. This shows the feasibility of the optically driven microstructures as a tool for DNA manipulation. In case of failure to capture DNA, a DNA molecule moves out of the space between two microstructures, as they approach each other. However, the detailed motion of a DNA molecule in the space surrounding the microstructures cannot be visualized in these experiments, because the autofluorescence of the microstructures and a random-coiled molecule hampers the observation. Two approaching microstructures extrude the aqueous solution between them. Thus, the failure of a DNA capture suggests that the flow induced by the extrusion carries the molecule out. These results show that large surface areas, between which the DNA molecule is pinched, improves the capture rate. A microstructure larger than the size tested here, however, results in a lower trapping force, which makes manipulation using optical tweezers difficult. In addition, such a large structure could potentially be subject to physical interference from the surface of a glass substrate. These results led us to select the dimensions of blockB as being suitable for the design of microchopsticks.

Microchopstick geometry

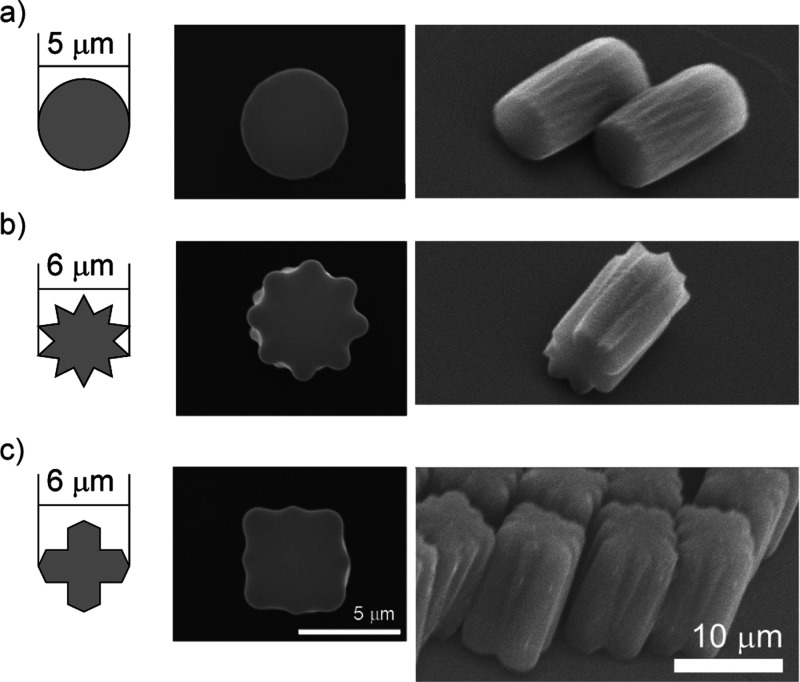

We developed microstructures of three geometries (circle, gearA, and gearB; Fig. 5) to evaluate the effect on DNA handling, with sizes comparable to that of blockB. The microstructures were slightly expanded due to light diffraction in the exposure process.25 In particular, gearB was different from the mask pattern and had the shape of a rectangular parallelepiped with grooves on the sidewall. The circle and gearA structures had a cylindrical geometry, whereas gearB and blockB were rectangular. The gearA and gearB structures had grooves on the surface to aid DNA capture.

FIG. 5.

Microchopstick for evaluating the effect of shape on DNA manipulation. Left: mask pattern (computer-aided-design layout). Center and right: SU-8 Microstructures. (a) Circle. (b) GearA. (c) GearB.

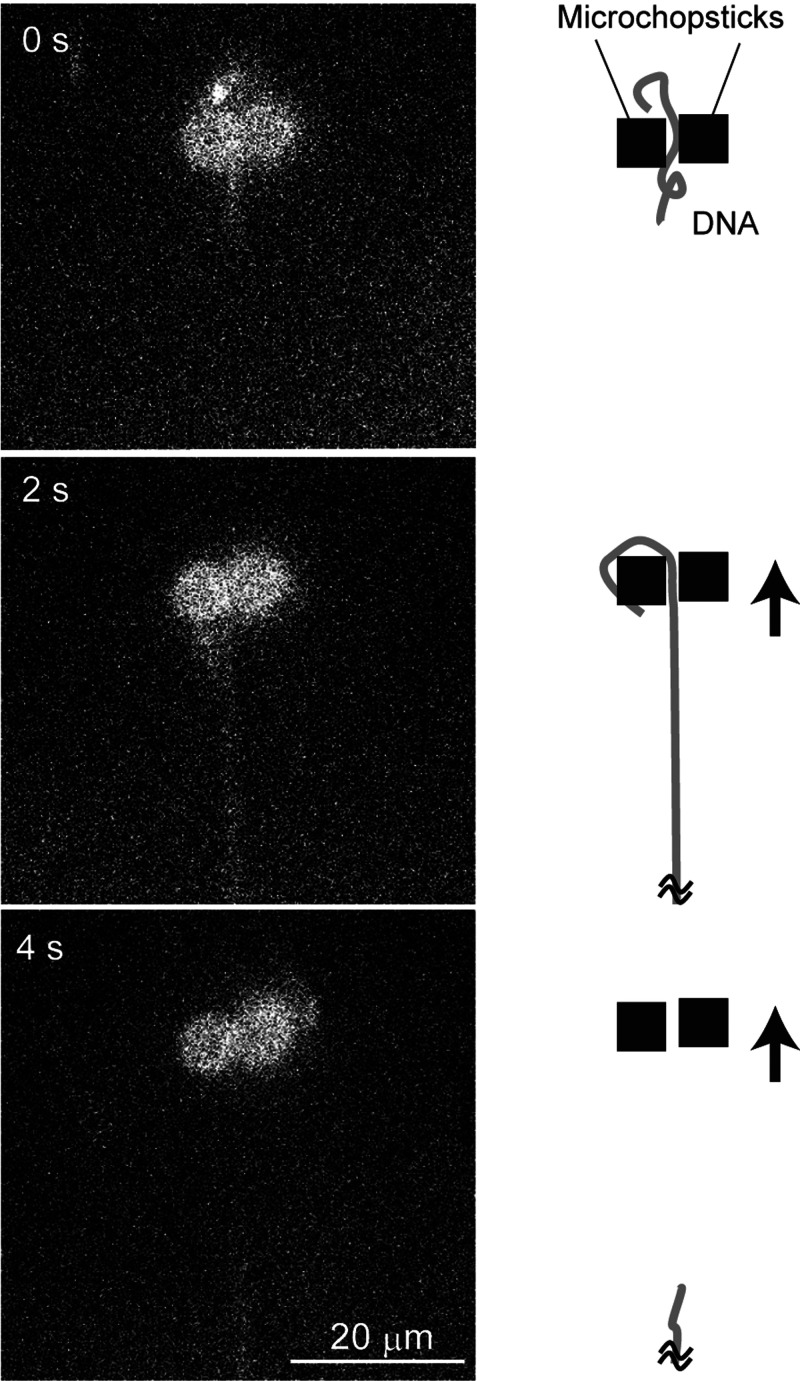

Single DNA molecules were captured and manipulated successfully using two microstructures driven by two laser beams (Fig. 6, Multimedia view). The DNA molecules were released when their elongation reached a specific limit. We defined this as the manipulation length and compared its value between four geometries (blockB, circle, gearA, and gearB) to evaluate their performance.

FIG. 6.

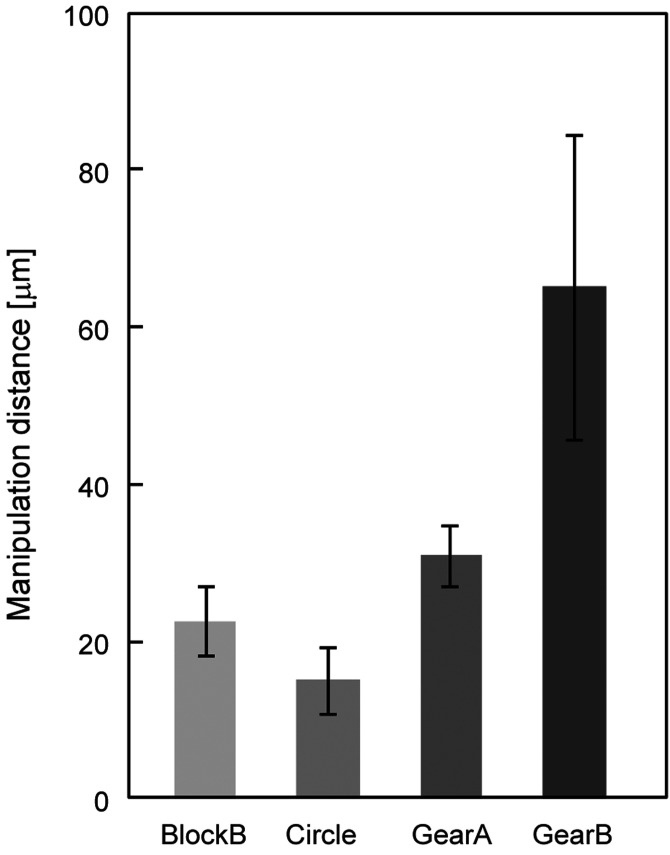

The manipulation lengths of blockB, circle, gearA, and gearB were 22.5, 15.0, 30.8, and 65.0 μm, respectively (Fig. 7). The results show that rectangular geometry allowed greater manipulation lengths than cylindrical. This could be due to the fact that the area of the rectangular structures where a DNA molecule is sandwiched is larger than that of cylindrical ones. The structures with grooves on the sidewalls also showed greater manipulation lengths than those without grooves, both in rectangular and cylindrical geometries. These results indicate that the microchopstick geometry governs the efficiency of manipulation of individual DNA molecules. The drag force exerted on a linear molecule tethered to a moving object is calculated as a shear force on the sidewall of a moving rod,

| (4) |

where L, b, and r are the length, diameter, and distance from the center axis of the rod, respectively. This shows that the force is linearly dependent on the length of the DNA molecule and the velocity gradient on the molecule. When a DNA molecule is manipulated more quickly and over greater distances, Fd will exceed the force acting on the part of DNA captured between microchopsticks, the frictional force Fc, resulting in the release of the DNA molecule. Hence, raising the upper limit of Fc, thereby essentially tightening the grip with the microstructures, is key to the development of efficient DNA handling. The frictional force between a DNA molecule and the microchopsticks should be derived from the electrostatic interaction and the viscous motion of the liquid trapped between them. A DNA molecule is negatively charged in typical buffer condition.26 Thus, inducing a positive charge on the surface of the microchopsticks will improve Fc, although such surface characteristics would also cause inevitable absorption,27 preventing further manipulation. This suggests that hindering the flow of the fluid in the space between the microchopsticks would be an effective approach for improving DNA manipulation. Two microstructures facing each other form a narrow channel containing a DNA molecule between them. Reducing the space increases its flow resistance. This prevents the flow induced by the slipping motion of the captured DNA molecule, improving Fc. The geometries of the microchopsticks determine the properties of the fluid space between them, which contributes to the viscous motion and brings about a difference in the manipulation length. Nanofabrication on the wall of the microstructures could potentially improve the manipulation length by trapping the DNA molecule in a space at the nanometer scale, though typical nanofabrication techniques lack the throughput suitable for fabricating a large number of microchopsticks, which is required for feasible handling under an optical microscope. To reveal the detailed mechanism of the manipulation requires the imaging of the dynamics of a DNA molecule in a nanometer-size space between movable walls though it still remains a technical challenge.

FIG. 7.

Manipulation distance of four shapes of microchopsticks (N = 7). Error bars show SD.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated the manipulation of individual chromosomal DNA molecules using optically driven microchopsticks which are intended for use in nanotechnology-based DNA analysis. We evaluated the microchopsticks in terms of their dimensions and geometries. The results of the DNA capture rate show that a block size of 10 × 5 × 4 μm3 is adequate for capturing single DNA molecules. Yeast chromosomal DNA molecules were successfully manipulated using microchopsticks under an optical microscope. The microchopsticks that were rectangular parallelepipeds in shape with grooves on the sidewalls showed the most effective DNA manipulation in terms of the manipulatable length. These results indicate that the geometry of the microstructure is a key factor for effective on-site manipulation. The insights obtained here may lead to the development of effective tools for chromosomal DNA analysis based on the observation of single molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by the PRESTO (JPMJPR14FB) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST); the JSPS KAKENHI (Nos. 18K18837, 18K06175, and 20H02118) of the Ministry of the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); the Sumitomo Foundation; the Japan Association for Chemical Innovation; and the matching fund of AIST-Shikoku and Kagawa Univ. The work was partly conducted at the Kagawa University Nano-Processing Facility, supported by the “Nanotechnology Platform Program” of the MEXT.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parra I. and Windle B., Nat. Genet. 5(1), 17 (1993). 10.1038/ng0993-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bensimon A., Simon A., Chiffaudel A., Croquette V., Heslot F., and Bensimon D., Science 265(5181), 2096 (1994). 10.1126/science.7522347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalet X., Ekong R., Fougerousse F., Rousseaux S., Schurra C., Hornigold N., Van Slegtenhorst M., Wolfe J., Povey S., Beckmann J. S., and Bensimon A., Science 277(5331), 1518 (1997). 10.1126/science.277.5331.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabata H., Kurosawa O., Arai I., Washizu M., Margarson S. A., Glass R. E., and Shimamoto N., Science 262(5139), 1561 (1993). 10.1126/science.8248804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallardo I. F., Pasupathy P., Brown M., Manhart C. M., Neikirk D. P., Alani E., and Finkelstein I. J., Langmuir 31(37), 10310 (2015). 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada Y., Funatsu T., Murakami K., Nonoyama Y., Ishihama A., and Yanagida T., Biophys. J. 76(2), 709 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77237-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howorka S. and Siwy Z., ACS Nano 10(11), 9768 (2016). 10.1021/acsnano.6b07041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y., Chen D., Yue H., French J. B., Rufo J., Benkovic S. J., and Huang T. J., Lab Chip 13(12), 2183 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc90042h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilboa T., Garden P. M., and Cohen L., Anal. Chim. Acta 1115, 61 (2020). 10.1016/j.aca.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Head S. R., Komori H. K., LaMere S. A., Whisenant T., Van Nieuwerburgh F., Salomon D. R., and Ordoukhanian P., Biotechniques 56(2), 61 (2014). 10.2144/000114133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirano K., Baba Y., Matsuzawa Y., and Mizuno A., Appl. Phys. Lett. 80(3), 515 (2002). 10.1063/1.1435803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chemla Y. R., Biopolymers 105(10), 704 (2016). 10.1002/bip.22880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M. D., Yin H., Landick R., Gelles J., and Block S. M., Biophys. J. 72(3), 1335 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78780-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gosse C. and Croquette V., Biophys. J. 82(6), 3314 (2002). 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75672-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vlaminck I. and Dekker C., Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 453 (2012). 10.1146/annurev-biophys-122311-100544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumemura M., Collard D., Sakaki N., Yamahata C., Hosogi M., Hashiguchi G., and Fujita H., J. Micromech. Microeng. 21(5), 054020 (2011). 10.1088/0960-1317/21/5/054020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashiguchi G., Goda T., Hosogi M., Hirano K., Kaji N., Baba Y., Kakushima K., and Fujita H., Anal. Chem. 75(17), 4347 (2003). 10.1021/ac034501p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terao K., Washizu M., and Oana H., Lab Chip 8(8), 1280 (2008). 10.1039/b803753a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terao K., Masuda C., Inukai R., Gel M., Oana H., Washizu M., Suzuki T., Takao H., Shimokawa F., and Oohira F., IET Nanobiotechnol. 10(3), 124 (2016). 10.1049/iet-nbt.2015.0036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oana H., Nishikawa K., Matsuhara H., Yamamoto A., Yamamoto T. G., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y., and Washizu M., Lab Chip 14(4), 696 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC51111A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori H., Okeyo K. O., Washizu M., and Oana H., Biotechnol. J. 13(1), 1700245 (2018). 10.1002/biot.201700245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Happel J. and Brenner H., Low Reynolds Number Hydrodynamics, 1st paperback ed. (Springer, 1983). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gauthier R. C., Ashman M., and Grover C. P., Appl. Opt. 38(22), 4861 (1999). 10.1364/AO.38.004861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bustamante C., Smith S. B., Liphardt J., and Smith D., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10(3), 279 (2000). 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00085-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dentinger P. M., Krafcik K. L., Simison K. L., Janek R. P., and Hachman J., Microelectron. Eng. 61–62, 1001 (2002). 10.1016/S0167-9317(02)00491-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsay S. M., Tao N. J., DeRose J. A., Oden P. I., Lyubchenko Yu L., Harrington R. E., and Shlyakhtenko L., Biophys. J. 61(6), 1570 (1992). 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81961-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terao K., Kabata H., and Washizu M., J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 18(18), S653 (2006). 10.1088/0953-8984/18/18/S11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.