Abstract

Objective

To report the association of JC virus infection of the brain (progressive multifocal encephalopathy [PML]) during the course of sarcoidosis and the challenging balance between immune reconstitution under targeted cytokine interleukin 7 (IL7) therapy for PML and immunosuppression for sarcoidosis.

Methods

Original case report including deep sequencing (whole-exome sequencing) to exclude a primary immunodeficiency (PID) and review of the literature of cases of PML and sarcoidosis.

Results

We report and discuss here a challenging case of immune reconstitution with IL7 therapy for PML in sarcoidosis in a patient without evidence for underling PID or previous immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusions

New targeted therapies in immunology and infectiology open the doors of more specific and more specialized therapies for patients with immunodeficiencies, autoimmune diseases, or cancers. However, before instauration of these treatments, the risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and potential exacerbation of an underlying disease must be considered. It is particularly true in case of autoimmune disease such as sarcoidosis or lupus.

Progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML) is a devasting demyelinating disease of the brain white matter described for the first time by Äström and colleagues in 1958 in a context of hematologic malignancy. PML is the consequence of the glial cell opportunistic infection by the human JC virus (JCV). Although asymptomatic JCV infection usually occurs in childhood and remains clinically silent in adult throughout life, active JCV replication in the brain could occurs in primary or secondary immunodeficiencies (mainly AIDS and hematologic malignancies) leading to PML. Immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs such as natalizumab in MS or rituximab have already been linked to PML, and some cases have been reported in sarcoidosis with severe CD4+ lymphopenia.1 Currently, achievement of immune reconstitution is the only curative option. In this view, interleukin 7 (IL7) or anti-PD1 therapies have been suggested to help the control of JCV in standing the immune response to the virus.2–4

Case report

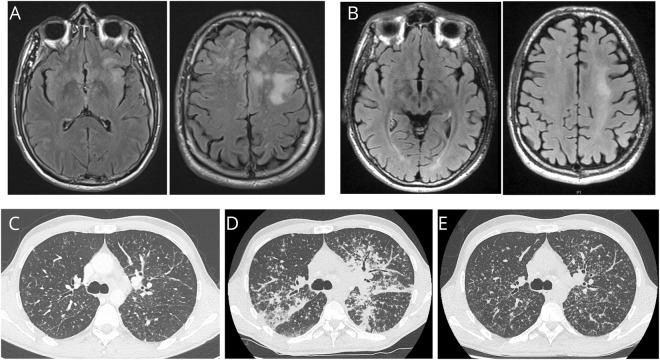

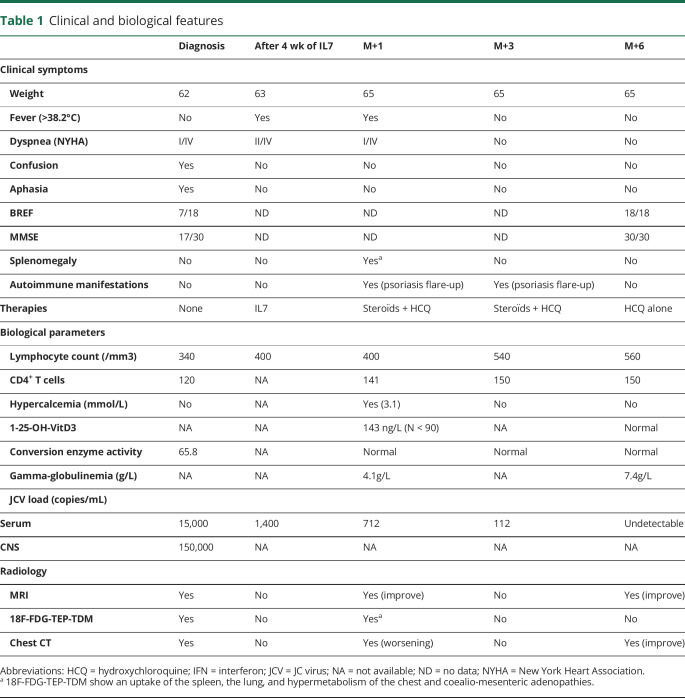

A 45-year-old man with PML was referred for acute respiratory failure and hypercalcemia after IL7 treatment in the context of underlying thoracic sarcoidosis. His medical history started 3 months with progressive dyspnea and cough revealing a mild micronodular infiltrate and mediastinal lymphadenopathy on the chest CT (figure). A bronchial biopsy showed a noncaseating granuloma. He developed severe lymphopenia up to 350/mm3 (normal > 1,500/mm3). Concomitantly, cognitive impairment (BREF 10/18; MMSE 25/30), frontal syndrome with perseverance, aphasia, and speech disturbance were noticed. First referred in psychiatry for unusual behavior, he was then hospitalized in the neurology department where the diagnosis of PML was made based on suggestive MRI demyelinating lesions of the white matter and positive JCV load in serum and CSF (figure and table 1). At this time, he did not receive any therapy for sarcoidosis. His cognitive impairment became worse (BREF 7/18; MMSE 17/30) during the first days of hospitalization, and a compassionate regiment of IL7 was started. Thanks to a 4-week regiment of IL7 at 10 mg/kg/wk, the neurologic symptoms improved, and the viral load felt to undetectable value (figure and table 1). Recent sharply demarcated erythema with fine scaling of seborrheic areas (presternal region and hairy zones of the face, scalp, and groin) along with erythemato-squamous plaques of the elbows was noticed, strongly suggestive of either sebopsoriasis or profuse seborrheic dermatitis. Skin biopsy with histopathologic examination demonstrated only nonspecific dermatitis without any granuloma, thus ruling out psoriasiform sarcoidosis. At the same time, the patient had hypercalcemia and required oxygen with a serious worsening of his micronodular lung infiltrate (figure). Bronchoalveolar lavage showed a predominant lymphocytosis (86%) with 5,8 CD4:CD8 ratio and negative microbiology. One 25-OH-vitamin D3 activity was elevated (143 ng/L, normal <90). Flare-up of sarcoidosis was suspected. He was then transferred to the intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure with a huge worsening of his interstitial lung disease treated with nasal oxygen, and hyperhydration was given with bisphosphonates (pamidronate 90 mg IV) to control calcemia (figure).

Figure. PML and sarcoidosis evolution.

MRI (axial, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery [FLAIR] sequences) of the brain at diagnosis of PML (A) and after IL7 therapy (B) showing a regression of inflammatory lesions of the white matter of the frontoparietal lobes predominant in the left hemisphere of the brain. TDM of the chest before IL7 showing light micronodular interstitial infiltrate related to sarcoidosis (C), dramatic worsening after 4 doses of IL7 therapy related to immune reconstituting syndrome (D), and improvement 3 months later after IL7 discontinuation, steroids, and hydroxychloroquine (E).

Table 1.

Clinical and biological features

Several recent observations and cases series support the hypothesis of underlined inherited immunodeficiency in PML. Moreover, granuloma is a frequent symptom revealing a primary immunodeficiency (PID) (in almost 20% of cases in common variable immunodeficiency for example). In this way, we decide to perform thorough immunophenotyping and genetic explorations. Analysis of his immune status as well as whole-exome sequencing analysis of the patient with his 2 parents did not reveal any evidence for PID.

IL7 was stopped. An immunosuppressive treatment of sarcoidosis was introduced and associated with a tight control of blood JCV load (table 1). Solumedrol (40 mg, twice a day) was started, carefully relayed after 5 days by moderate dose of oral steroids (prednisone 30 mg/d) with a decreasing protocol for 6 months and prophylactic treatments (cotrimoxazole and valaciclovir). In addition, hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/d) was started as a steroid-sparing agent. Under these therapies, sarcoidosis and psoriasis improved. PML did not relapse during the 6 months of follow-up. However, the lymphopenia persisted around 600/mm3.

Methods

Whole-exome sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from patient and parents' peripheral blood or saliva using standard protocols. Exome sequencing libraries were prepared with the Twist Library Preparation Kit and captured with Human Core Exome probes extended by Twist Human RefSeq Panel (Twist Bioscience, San Francisco, CA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Paired-end (2 × 75 bp) sequencing was performed on a NextSeq500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Before any processing, quality control was performed using FastQC. The raw reads data were next mapped using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool. For each sample, average target read coverage was at least 60-fold. After read mapping, further quality indicators were calculated from the resulting BAM file using SAMtools, Qualimap. Variant calling was performed using the GATK HalotypeCaller of the GATK software suite. The annotation was performed by VEP, the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. We focused only on protein-altering variants (missense, nonsense, splice site variants, and coding indels) with alternative allele frequencies <0.005 in the 1000 Genomes Project, the Genome Aggregation Database, the Exome Aggregation Consortium, and an internal exome database including ∼700 exomes. To identify potential causal variants, we further filtered the variants based on a de novo and recessive mode of inheritance.

Statistics

Data are presented as median (range) or frequency (%) with 95% CIs. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 7.0.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Discussion

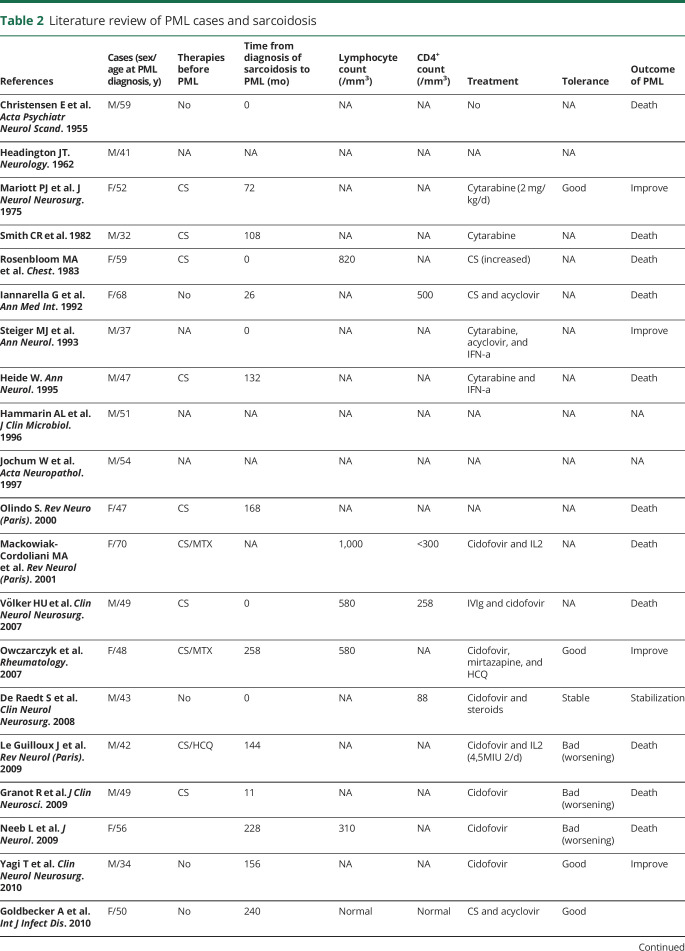

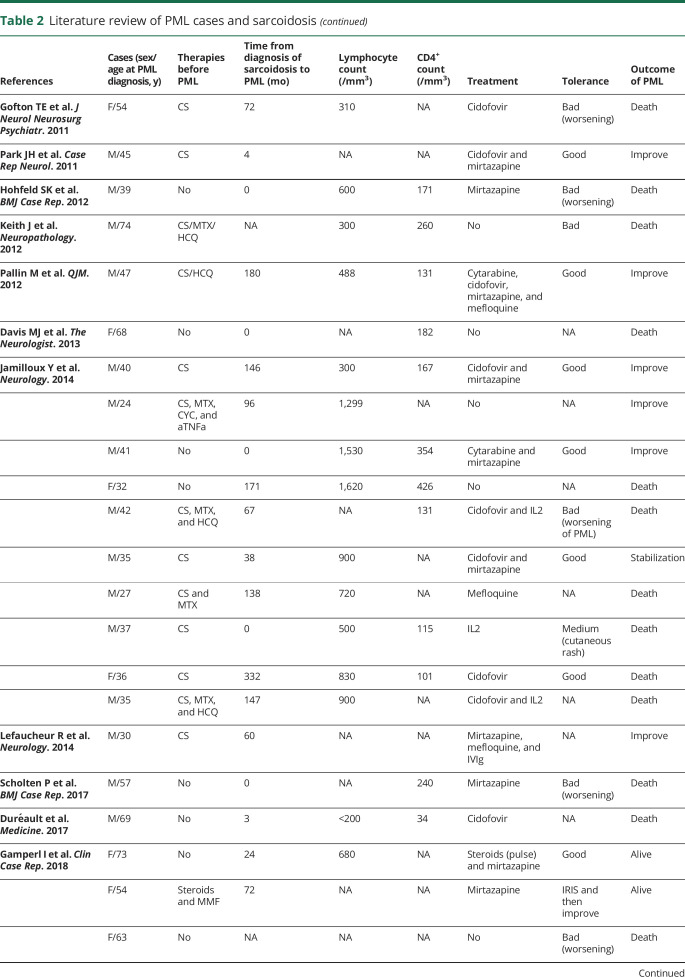

To date, only few cases of sarcoidosis and PML have been reported (table 2). The main cause of the immunodeficiency leading to such opportunistic infections in this situation remains unclear. Indeed, lymphopenia, and mainly the CD4+ lymphocytes decreased, is usually considered as a redistribution of cells (demargination) in the organs involved by the disease and is not considered at risk for infections. Nonetheless, some case reports or series report severe or opportunistic infections occurring in less than 5% of cases of sarcoidosis.5,6 The most frequent infections are Cryptococcus, mycobacterial infection, nocardiosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis, and Aspergillus infections. Their occurrence is closely linked not only to the severity (neurologic form of sarcoidosis) and activity of the disease but also to the immunosuppressive therapy (steroids in first and cyclophosphamide).5

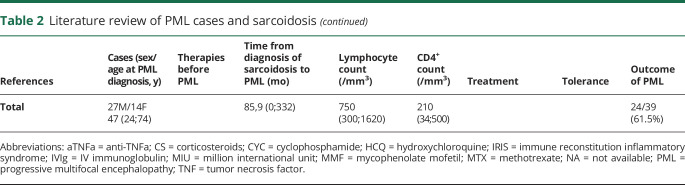

Table 2.

Literature review of PML cases and sarcoidosis

PML is rarer than other opportunistic infections in sarcoidosis with a very poor prognosis. Our review of literature (n = 41 cases) identifies a median age of 47 years (range 24–74 years) with a sex ratio (M/F) of 1.9 (table 2) and highlights a mortality rate of 61.5% at last follow-up. Unlike other opportunistic infections, PML may occur in untreated patients (table 2).1 In this context, it is of importance to make the differential diagnosis with neurosarcoidosis, which required the use of intensive immunosuppressive therapy. Patients with sarcoidosis and opportunistic infections, especially with no history of immunosuppressive treatment, may belong to a more sensitive subgroup of patients with inherited susceptibility factors. In this view, such factors described in inherited pediatric and familial cases of sarcoidosis involving autophagy pathway or T-cell activation pathway could be crucial for response against pathogens.7 Moreover, it is also important to consider the hypothesis of PID with granulomatous manifestations and opportunistic infections (PML) in some combined immunodeficiencies (i.e., Immunodeficiency, Centromeric region instability, Facial anomalies syndrome, DOCK8 deficiency, STAT1 GOF or other combined immunodeficiencies).8 In our case, we excluded the eventuality of an inherited error of immunity by several arguments: (1) the age at onset of the opportunistic infection and the past medical history of the patient and his family; (2) the late onset of lymphopenia with prior normal blood examinations; and (3) the whole-exome analysis that excluded a known mutation in PID-related genes.

PML, caused by invasive JCV infection of the brain, is a poor prognosis affection with a fatal outcome in weeks or months in the absence of immune reconstitution. Recently, IL7 cytokine therapy and anti-PD1 monoclonal therapy have been proposed to restore an immunity against JCV in a context of secondary immunodeficiency, with or without vaccination strategies.2,4 Before using such therapies, it is very important to consider, however, (1) the risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) and (2) the potential exacerbation of an underlying disease or the emergence of secondary immune/inflammatory manifestations. It is particularly true in case of autoimmune disease such as sarcoidosis or lupus in which imbalance in immune-activating cytokine such as IL7 (one of the most important cytokines to T-cell expansion and activation) could favor a flare. Mechanisms leading to the worsening of a previous inflammatory/autoimmune situation have already been described not only in PML associated with AIDS but also in apparently non-immunocompromised patients.9

In our case, the challenging point was to restore the immunity against JCV and to control the sarcoidosis activity. IRIS has been well described in HIV-infected patients as a paradoxical reaction after introduction of the treatment. Even if rare, IRIS can potentially occur in all granulomatous diseases and not just infectious ones.

In sarcoidosis, CD4 T-cell depletion is mainly linked to the margination process. Thus, the use of IL7 as a therapy for PML has probably favored the expansion and activation of CD4 T cells in tissue, explaining the IRIS in involved tissue (lung and lymph nodes) and hypercalcemia. We chose to introduce low dose of steroids and hydroxychloroquine to balance the related risk of PML resurgence and immune restoration syndrome associated with granuloma activity (hypercalcemia and acute lung injury) and sebopsoriasis flare.10

New targeted therapies in immunology and infectiology open the doors of more specific and more specialized therapies for patients with immunodeficiencies, autoimmune diseases, or cancers. Nonetheless, some imbalance has to be finely found to avoid some severe complications. This is the beginning of a new era for physicians involved in these fields.

Glossary

- BREF

“Batterie rapide d'efficience frontale” test (also called Dubois' test)

- IRIS

immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

- JCV

JC virus

- MMSE

Mini Mental State Examination

- PID

primary immunodeficiency

- PML

progressive multifocal encephalopathy

- STAT1 GOF

gain-of-function in STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 1) gene

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

Supported by the European regional development fund (European Union) INTERREG V program (project PERSONALIS) and the MSD Avenir grant (Autogen project).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Jamilloux Y, Néel A, Lecouffe-Desprets M, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with sarcoidosis. Neurology 2014;82:1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortese I, Muranski P, Enose-Akahata Y, et al. Pembrolizumab treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1597–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter O, Treiner E, Bonneville F, et al. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with nivolumab. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1674–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sospedra M, Schippling S, Yousef S, et al. Treating progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with interleukin 7 and vaccination with JC virus capsid protein VP1. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1588–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duréault A, Chapelon C, Biard L, et al. Severe infections in sarcoidosis: incidence, predictors and long-term outcome in a cohort of 585 patients. Medicine 2017;96:e8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamilloux Y, Valeyre D, Lortholary O, et al. The spectrum of opportunistic diseases complicating sarcoidosis. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.In the frame of GSF (Groupe Sarcoïdose France), Calender A, Rollat Farnier PA, Buisson A, et al. Whole exome sequencing in three families segregating a pediatric case of sarcoidosis. BMC Med Genomics 2018;11:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerbe CS, Marciano BE, Katial RK, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in primary immune deficiencies: stat1 gain of function and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:986–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krey L, Raab P, Sherzay R, et al. Severe progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and spontaneous immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in an immunocompetent patient. Front Immunol 2019;10:1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tripathi SV, Leslie KS, Maurer TA, Amerson EH. Psoriasis as a manifestation of HIV-related immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:e35–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.