Abstract

Here we report a novel mechanism for triggering drug release in the polydopamine (PDA)-coated magnetic CuCo2S4 core-shell nanostructure by glutathione (GSH) triggering degradation of PDA for releasing. In the design, we used PDA coated CuCo2S4 as the nanocarriers with polyethylene glycol and folic acids targeting molecules to ensure the safe delivery of doxorubicin (DOX) to cancer cells. In addition, the controlled release could be enforced by taking the advantage of PDA pH sensitivity to the tumor acidic environments. The targeting and treatment on HeLa cancer cells were very effective and the killing was more efficient at higher levels of GSH. Furthermore, the system designed not only could be used for drug delivery but also could combine photothermal therapy with chemotherapy in a synergetic way. Plus, the system could be used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was beneficial for imaging-guided treatment.

1. Introduction

Cancer is among the most dangerous diseases that threatens human health, and significant technological progress has been achieved in combating the disease.1,2 Among which, various targeted delivery and controlled release systems have drawn considerable attention for their utility in cancer treatment. A smart controlled release system for intracellular drug delivery is crucial for cancer therapy since most anticancer drugs are severely toxic, especially those that are used in chemotherapy. Furthermore, chemotherapy is not always sufficient for cancer treatment since cancer cells may develop resistance to it.3 To overcome these issues, a number of nanoparticles have been used to build multimodal diagnosis and treatment platforms in order to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects.4–7 In particular, the combination of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy, that is therm-chemotherapy, has proven to be an effective strategy for this purpose.8 By localizing treatment with site specific delivery, some side effects may be ameliorated.9,10 Furthermore, combining different modes treatments can prove useful for combating resistance in cancer cells and increasing the overall effectiveness of treatment. 11

Nanoparticles have attracted enormous scientific interest for their abilities to as drug-delivery carriers, e.g., liposomes,12 vesicles,13 micelles,14 dendrimers15 and others.16,17 Here, we focused on copper chalcogenide (CuS) nanoparticles. CuS nanoparticles exhibit favorable optical and electrical properties and have found extensive biological applications such as sensing,18 drug delivery,4 photothermotherapy19, photodynamic therapy,20 and bioimaging.21 In general, larger copper sulfide particles, 50–200 nm, with porous structures are used as drug delivery carriers and photothermal agents, whereas smaller ones that are <30 nm are suitable as photothermal and contrast agents.22 However, the photothermal conversion efficiency of most binary chalcogenides is less than 60%.23–25 Nowadays, nanoscale copper-based ternary chalcogenides are being investigated for their capacity to improve the photothermal conversion efficiency and to achieve new modalities in the treatment platform.26–28 For example, the introduction of the large X-ray attenuation coefficient of bismuth in Cu3BiS3 facilitated computed tomography (CT) imaging.29 In addition to the inherent near infrared region (NIR) imaging capabilities of CuS, the ternary CuCo2S4 was endowed with MRI capacity due to the contribution of cobalt.30 However, good carriers and targeting are needed in order to have more efficient treatment.

It is known that PDA exhibits excellent biocompatibility and displays the main characteristics of melanin in optics and electricity.31 Another favorable feature of PDA lies in its chemical structure which contains various functional groups, including catechols, amines and imines. These functional groups allow PDA to be tightly attached to the surface of nanomaterials and serve as bridges or coatings for facilitating further modifications,32,33 as demonstrated by the functionalization with folic acid,34 nucleic acid,35 peptide chains36 and other functional groups.37 In addition, PDA can serve as an ideal photothermal agent due to its absorption in the NIR region.38 In light of these features, diverse PDA-based nanoparticles have been fabricated for drug delivery and cancer treatment.32,39 The release of drugs from most of these carrier systems involve a pH-dependent mode.40,41 Here we report a novel mechanism for triggering drug release in the PDA-coated magnetic CuCo2S4 core-shell nanostructure by GSH triggering degradation of PDA for releasing. In the construction of the multifunctional nanocarrier, magnetic CuCo2S4 was chosen as the core, serving as MR contrast agent and photothermal agent. The PDA shell served as a photothermal agent and a bridge to bind with the target groups. Folic acid was used as a targeted unit, while NH2-PEG-NH2 was used to improve the hydrophilicity and biocompatibility of the nanocomposites. DOX was loaded into the nanocarrier system in order to achieve a synergic combination of chemotherapy with photothermal therapy.

2. Experimental section

Preparation of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanocomposites and drug loading.

CuCo2S4/PDA:

CuCo2S4 nanoparticles were prepared according to a previously reported approach.30 Then, 0.021g CuCo2S4 was dissolved in 20 mL dopamine hydrochloride solution (0.1 mg mL−1, dissolved in 10 mmol L−1 Tris-HCl at pH 8.5) under continuous sonication for 90 min at room temperature. PDA decorated nanocomposites, CuCo2S4/PDA, were obtained by centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 20 min, followed by washing with DI water twice, and finally with ethanol and dried in vacuum.

CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA:

CuCo2S4/PDA nanoparticles were dispersed in 20 mL Tris-HCl (10 mmol L−1, pH 8.5). 0.010 g NH2-PEG-NH2 (Mw=3400) dissolved in 1 mL DI water was added dropwise into the above solution under sonication for 30 min. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG nanoparticles were obtained by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 15 min and washed with DI water three times. 20 mg FA was dissolved in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with 20 mg EDC and 20 mg NHS and shook in the dark for 3 h. The CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG nanoparticles were then dispersed in 20 mL phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4, 10 mmol L−1) by adding 1 mL of the above FA solution (DMSO, 0.020 g mL−1). After shaking for 3 h at room temperature in the dark, the mixture was centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 15 min and washed with PBS three times over. The final product, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanoparticles, were obtained and dispersed in PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mmol L−1).

DOX loading on CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanocomposites:

20, 40, 60, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240 and 320 μL of DOX aqueous solutions (5 mg mL−1) were mixed with 150 μL of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA suspension (1 mg mL−1), and the volume of the mixture was adjusted to 1 mL with PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mmol L−1). After shaking the mixture overnight at room temperature, the mixtures were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min and washed with PBS three times. The product, DOX-loaded CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanocomposites (CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX), were then collected. The concentration of residual DOX in the supernatant was detected with spectrophotometry by measuring the absorbance at 500 nm. The loading ratio (LR) of DOX to CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA was expressed in equation (1), where mDOX and muDOX represents the mass of DOX before loading and that remained in the supernatant, while mCuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA denotes the mass of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanocomposite.

| (1) |

Photothermal performance.

The photothermal behaviors of CuCo2S4 nanoparticles (200 μg mL−1), CuCo2S4/PDA nanocomposites (22, 55, 110, 220 μg mL−1, corresponding to 20, 50, 100, 200 μg mL−1 CuCo2S4, respectively) were evaluated by irradiating their aqueous solutions with a continuous wave fiber-coupled diode laser source (808 nm, 1.5 W cm−2) for 10 min, and the temperature of the aqueous solution is then monitored by using a thermometer (IKA Ltd).

In vitro bi-trigger drug release.

For in vitro drug release experiments, 2 mg CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites (with 1 mg DOX loaded) were dispersed in 2 mL of PBS at different pH values (pH 5.5, 6.3, 7.4) and in the presence of various concentrations of GSH (0, 5, 10, mmol L−1). The mixture was continuously incubated at 37 °C, followed by centrifugation at given time intervals (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 h) to collect the supernatant. The amount of released DOX was estimated by UV-vis absorption spectrophotometry at 500 nm. CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX sediment was then resuspended in fresh PBS.

The releasing ratio (RR) was calculated by using equation (2), where WrDOX represented the mass of DOX in the supernatant, while WlDOX denotes the mass of DOX loaded on the nanocarrier.

| (2) |

In vitro cytotoxicity assay.

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at standard culture (37 °C, 5% CO2). The HeLa cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2.5×104 cells per well and incubated for 2 h with 5, 10 mmol L−1 GSH, respectively. Afterwards, the cells were washed with PBS to remove the excessive GSH. DMEM with various concentrations of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX was added to the above cells and incubated for 24 h. The cell viability was then evaluated with an MTT assay. 20 μL MTT (5 mg mL−1) solution was added to each well of the plate and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. 200 μL DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals after removing the media. Thereafter, the absorbance at 490 nm of each well was measured by a microplate reader (BioTek, American).

For in vitro photothermo-chemotherapy, the cells were first incubated with various concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40 μg mL−1) of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX for 4 h. After being irradiated by an NIR laser (0.8 W cm−2) for 5 min, the cells were further incubated for an additional 20 h. The viabilities of cells were then evaluated by an MTT assay.

In vitro cellular uptake.

For the purpose of observing the cellular uptake of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites, the cells were plated in 35 mm glass bottomed culture dishes (2.5×105 cells/well) and grown for 24 h. Afterwards, DMEM containing 100 μg mL−1 CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (with 50 μg mL−1 loaded DOX) and free DOX (50 μg mL−1) were added and the mixture was incubated for 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h. The cells were washed with PBS and subsequently imaged via a FV 1200 confocal fluorescence microscopy by excitation at λex 488 nm (Olympus, Japan).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA aqueous solution was scanned under a 0.5 T clinical MRI scanner at room temperature. The relaxation rate r1 was calculated as the reciprocal of T1 (r1 = 1/T1) at various cobalt concentrations as determined by ICP-MS (7500a, Agilent). For in vivo MRI, healthy Kunming mice were intravenously injected with CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA (at a dosage of 4 mg Co kg−1, i.e., 11 mg CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA kg−1) for MR imaging. T1-weighted MR images were obtained and analyzed on a 0.5 T clinical MRI scanner equipped with a special animal imaging coil. Healthy Kunming mice (20−25 g) were received from the animal experiment center of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China) for in vivo MRI studies. Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, published by the National Academy Press in 1996. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China) reviewed and approved the study protocols.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION.

Characterizations.

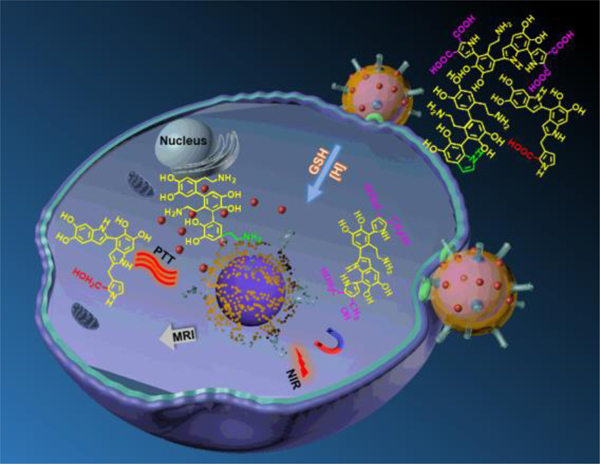

The strategy to synthesize CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX is illustrated in Scheme 1. PDA is coated onto the magnetic CuCo2S4 surface through an in - situ self-polymerization process yielding a core-shell structure CuCo2S4/PDA. The modification of CuCo2S4/PDA with amine-terminated PEG and FA is realized by covalent conjugation, i.e., nucleophilic amine groups in PEG react with quinone and dihydroxyindole/indolequinone groups in PDA by means of Schiff base reactions and Michael addition reactions, respectively.42 CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites are obtained by loading DOX onto CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration for the drug-release of DOX from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites via the depolymerization of PDA in the presence of GSH.

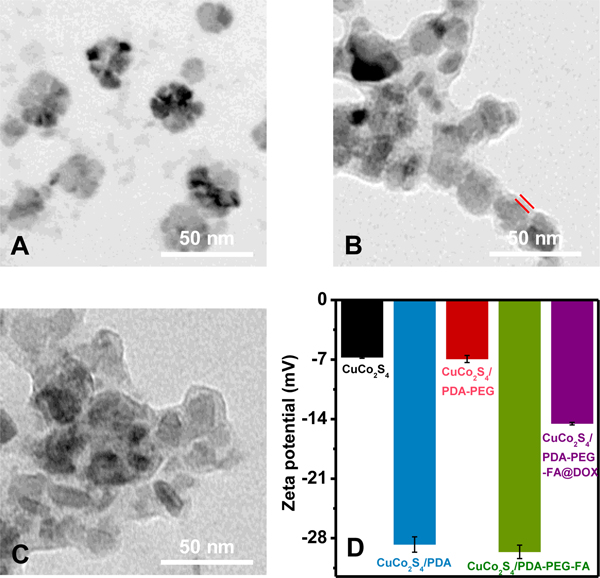

CuCo2S4 nanoparticles with an average size of 30 nm are prepared through a hydrothermal approach as shown in Figure 1A. The XRD pattern in Figure S1A confirms their cubic spinel phase (JCPDS no. 42–1450). TEM images of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanoparticles demonstrate the presence of PDA-PEG-FA shell with a thickness of ca. 5 nm (Figure 1B). The loading of DOX causes virtually no change on the size of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (Figure 1C). Zeta potential values of the corresponding nanocomposites obtained in each step are shown in Figure 1D, where the CuCo2S4 aqueous solution exhibits a weak negative potential (−6.7 ± 0.1 mV) ascribed to the presence of a large amount of polyvinylpyrrolidone K30 (PVP K30).4 The coating of PDA reduces the zeta potential to −28.7 ± 0.9 mV, implying the deprotonation of the phenolic hydroxyl groups or carboxylic group of PDA at neutral pH.5–8 The introduction of NH2-PEG-NH2 results in an increase of zeta potential to −6.9 ± 0.4 mV due to the presence of enormous amino groups. The incorporation of FA significantly decreased zeta potential to −29.6 ± 0.8 mV, which was attributed to the carboxylic groups in FA structure.46 Finally, the loading of DOX enhances the zeta potential value of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX to −14.5 ± 0.2 mV because the positively charged amino groups on DOX neutralized the partial negative charge of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA.

Figure 1.

TEM images of CuCo2S4 (A), CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA (B) and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (C). Zeta potential values of CuCo2S4 CuCo2S4/PDA, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (150 μg mL−1 for CuCo2S4, 20 μg mL−1 for the loaded

UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of CuCo2S4, CuCo2S4/PDA, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX are illustrated in Figure S2. CuCo2S4 nanoparticles show an absorption in the NIR region (700–900 nm), and an increase on the absorbance intensity is observed after coating PDA, indicating that the photothermal effect of CuCo2S4 would be improved. No obvious changes are found in the NIR region after grafting NH2-PEG-NH2 and loading DOX. However, in the case of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA, two new absorption bands are observed at 280 nm and 350 nm, which are consistent with the characteristic absorptions of FA. The absorption band at 514 nm in CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX is attributed to DOX.

Further, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed and the curves are shown in Figure S3. The weight loss of CuCo2S4, CuCo2S4/PDA, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA was 72.1%, 60.5%, 57.9% at 800°C, respectively. Thus, the relative amount of PDA is about 11.6%. 2.6% of PEG and FA are grafted to the surface of PDA.

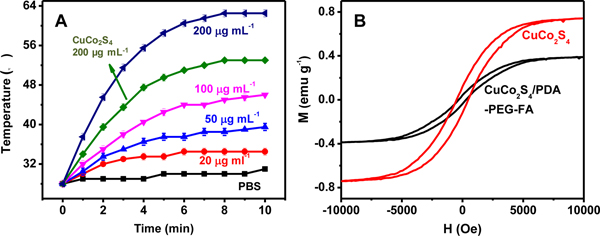

Photothermal and magnetic performance

The photothermal performances of CuCo2S4 and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA are investigated, and the heating curves of their solutions upon exposure to 808 nm laser (1.5 W cm−2) are given in Figure 2A. The photothermal effect of both CuCo2S4 and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA exhibits a distinct concentration-dependent mode. At a concentration of 200 μg mL−1 CuCo2S4, a temperature elevation of 25°C was observed within a 10 min irradiation. Meanwhile, the same amount of CuCo2S4 in CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA gives rise to a much improved photothermal effect, causing a temperature elevation of 34.5°C, which is attributed to the presence of PDA. For a comparison, CuS nanoparticles are previously reported to produce a temperature elevation of 20°C at identical experimental conditions.4 This means PDA and folic acid targeting can largely improve the photothermal efficacy.

Figure 2.

Photothermal curves of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA at various concentrations (corresponding to 20, 50, 100, 200 μg mL−1 CuCo2S4) under irradiation at a fixed energy level of 1.5 W cm−2. The arrow points to that of CuCo2S4 at a concentration of 200 μg mL−1 (A). Magnetization curves for CuCo2S4, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA at room temperature (B).

The magnetization curves at room temperature for CuCo2S4 and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA (Figure 2B) demonstrate that their saturated magnetizations are estimated to be 0.74163 and 0.38883 emu g−1, respectively. Although the coating/encapsulation of PDA, PEG and FA leads to the decrease of saturated magnetization, it is quite sufficient for practical applications in the present study.

The loading and responsive release of DOX in CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX.

CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA was applied as a drug nanocarrier for DOX. Figure S4 illustrates a superb loading capacity of DOX for CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA, corresponding to a loading ratio (LR) of up to 3.7 at a DOX concentration of 1400 μg mL-1. A comparison of LR values for some recently reported drug-delivery vehicles is given in Table S1, where CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA exhibits a highest LR, while those for most of the other drug-delivery vehicles are usually less than 2. The high drug loading is mainly attributed to extraordinarily robust adhesion of PDA. Mussel could attach to diverse substrates with high binding strength due to the presence of 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA). The molecular structure of PDA is similar to that of DOPA, which contributes to high adhesion. Furthermore, due to amount of aromatic conjugated structures of DOX and PDA, they exhibit intense π–π stacking and hydrophobic interaction. Moreover, as illustrated in Figure 1D, the loading of DOX enhances the zeta potential value of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX from −29.6 ± 0.8 mV to −14.5 ± 0.2 mV. This confirms that electrostatic interactions between DOX molecules and drug-carriers (CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA) also lead to the high loading.47–49

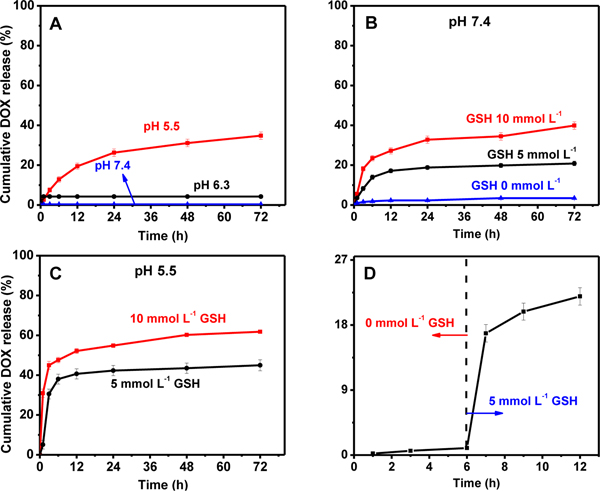

The dependence of in vitro controlled release of DOX on stimulus was subsequently investigated at 37 °C within 72 h, by using PBS to simulate the physiological environment with different pH values (pH 5.5, 6.3, 7.4). As shown in Figure 3A, virtually no leakage of DOX was observed at pH 7.4, and a very low leakage of only ca. 4.2% is recorded at pH 6.3. In an acidic medium at pH 5.5, however, a cumulative release rate of 39.8% was achieved. Amino-group structures of DOX molecules protonate easily under acidic conditions. Attributed to the protonation, the hydrophilicity and solubility of DOX increased compared to the hydrophobicity of DOX. Thus, DOX could be released in the micro-acid environment of the tumor.41 In addition, the pH-responsive release of DOX may also be associated with the degradation of PDA framework.40 This is another advantage that can be taken to facilitate the controlled release of drugs to tumor acidic environments.

Figure 3.

DOX release profiles from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX at a single stimulus of pH 5.5, 6.3 and 7.4 (A); DOX releasing profiles with GSH stimulus of various concentrations (0, 5, 10 mmol L−1) at a fixed pH value, i.e., pH 7.4 (B); DOX releasing profiles with combined stimuli of pH and GSH, at pH 5.5 and in the presence of 5 or 10 mmol L−1 GSH (C); a further confirmation of GSH-responsive DOX release behavior with no GSH at the first 6 h, and GSH introduction thereafter for another 6 h (D).

Recently, many redox-responsive drug carriers triggered by GSH have been developed. 50, 51, 52 These redox-responsive drug carriers usually contain disulphide bonds or di-selenium bonds, which could be cleaved by GSH. The intracellular GSH concentration in cancer cells generally falls into the range of 2–10 mmol L−1, which is 100–1000 folds higher than that of normal cells. Thus, redox-responsive drug carriers are selectively degraded in cancer cells and drugs are controlled released by the redox stimulus. As an intracellular stimulus, GSH exhibits an obvious triggering effect on the release of DOX from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX. The GSH-dependent releasing behavior of DOX at various concentrations of GSH, e.g., 0, 5 and 10 mmol L−1, is thoroughly investigated at a fixed pH value, pH 7.4. Figure 3B clearly illustrates a rapid release of DOX in the presence of GSH, and a distinct increase of the drug release is obtained with the increments of GSH levels, wherein a release ratio of 39.9% is observed after 72 h at a DOX concentration of 10 mmol L-1. At identical conditions, however, no release of DOX is recorded in the absence of GSH (Figure 3B). Thereafter, the combined stimulus responsive release behaviors of DOX were further studied at pH 5.5 and in the presence of 5 mmol L−1 or 10 mmol L−1 GSH, respectively. A cumulative release of 61.9% for DOX was obtained within 72 h by combining the pH and GSH dual stimuli at a GSH level of 10 mmol L−1 (Figure 3C), with respect to 39.8% for that achieved with a single stimulus at pH 5.5 which further verified the suggestion. A cumulative release of 61.9% for DOX is unsatisfying. DOX are not easy to depart from oligomers and fragments of PDA because of high adhesion of PDA. In order to improve drug release properties, preparation of more degradable PDA shell would be a feasible method due to the rapid collapse of nanocarrier. We are trying to prepare PDA shell with disulfide bonds, which would be more easily degraded by GSH.

The GSH-stimulus release behavior of DOX from the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocarrier composites by GSH was further confirmed, as depicted in Figure 3D. DOX loaded on CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX remain stable at pH 7.4 without release, while a sudden release of DOX is encountered once 5 mmol L−1 GSH is added into the medium at a fix pH 7.4.

Further studies have been conducted to demonstrate the versatility of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA as a nanocarrier for loading other drug and its subsequent release based on GSH stimulus. In this particular case, curcumin (Cur) was used as a model. The concentration of residual Cur in the supernatant was determined by measuring with spectrophotometry at 425 nm. In the presence of 10 mmol L−1 GSH, 26.1% of Cur was released from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@Cur at pH 7.4 within 72 h. At the same conditions, however, only ca. 6.9% of Cur is released without GSH (Table S2). In contrast to the release of DOX from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX, the release of Cur was less sensitive to pH variation, i.e., the variation of pH value causes virtually no effect on the release of Cur, i.e., ca. 7.3% of Cur was released at pH 4.7 in the absence of GSH (Table S2). The combined stimuli by both 10 mmol L−1 GSH and pH 4.7 give rise to a release of 49.2% for Cur, which was much higher than those for a single stimulus of either 10 mmol L−1 GSH or pH 4.7. The observations herein well demonstrate the wide range applicability of GSH stimulus for drug release in PDA-based drug delivery vehicles.

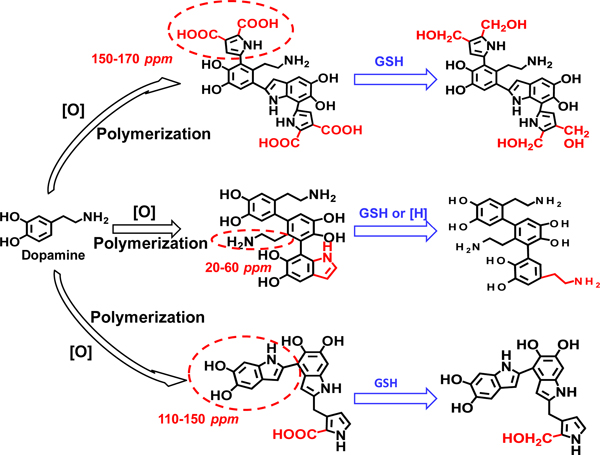

The previous studies suggest that the polymerization process of PDA contains an oxidation process.29, 49 It is speculative that the reductive GSH may change or even destroy the polymerization state of polydopamine, and as a result to disrupt the interaction between PDA and DOX, and thus trigger the release of the drug.

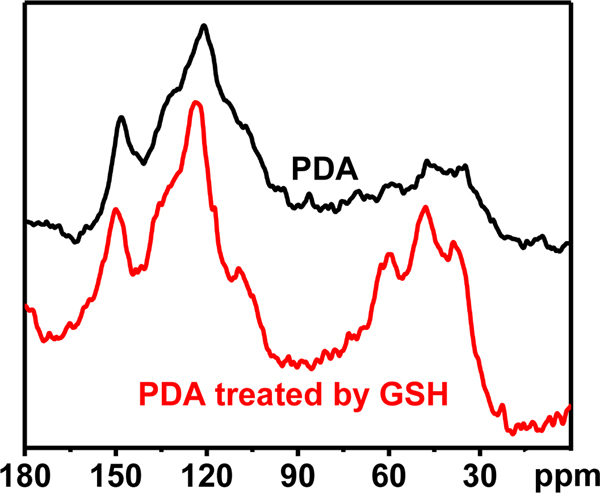

13C solid-state NMR spectra of PDA and GSH-treated PDA were recorded to further elucidate the above hypothesis (Figure 4). For the treatment by GSH, PDA is soaked in PBS (pH 4.7, containing 10 mmol L−1 GSH) for 72 h. In comparison with the untreated PDA, GSH-treated PDA exhibits intense aliphatic resonances at chemical shifts around δ 40, 50 and 60 ppm, and more relatively well-resolved bands in the sp2 region around δ 110, 120, 150 ppm, which indicates a substantial proportion of uncyclized units. This confirms that open-ring behavior of PDA due to the effect of GSH or acidic medium. In addition, the presence of stronger resonance at around δ 150 ppm, and the decreased peak area at δ 170 ppm suggest high proportions of OH-bearing carbons generated at the expenses of carboxylic acid groups and/or other carbonyl-type groups (-COOH) via reduction reaction. Specifically, the key cyclization product of dopamine, catechol moiety named 5,6-dihydroxyindole unit, is reduced by GSH (Figure 5).50

Figure 4.

13C solid-state NMR spectra of native PDA and PDA after treated with 10 mmol L−1 GSH for 72 h.

Figure 5.

The preliminary overall view of main reaction pathways involved in the depolymerization of PDA and PDA-based nanocarriers stimulated by GSH. It involves two parallel interactions and transformations, i.e., the open-ring behavior in the presence

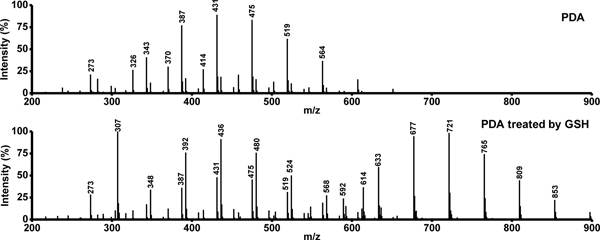

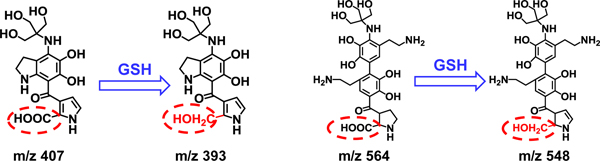

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was employed to obtain more evidences for prove the degradation of PDA by GSH-triggering. The mass spectra of native PDA and that after treated by 10 mmol L−1 GSH for 72 h are illustrated in Figure 6, where significant differences are found between the native and the GSH-treated PDA. Due to the heterogeneity and insolubility of PDA in the solvents tested (N, N-dimethylformamide, acetonitrile, DI water), the mass spectrum of native PDA shows only a few oligomers within the range of 300<m/z<600. As shown in Figure S5, the peaks of native PDA are also identified for the GSH-treated PDA. The major peaks at around m/z of 303 and 454, i.e., 274, 371, 393, 518, are attributed to the physical trimer as proposed in previous studies. Although the major peaks within 300–600 resemble native and GSH treated PDA, it is noticeable that the peaks close to m/z values of 348, 392, 436, 480, 524, 592 are significantly increased in GSH-treated PDA with respect to those observed for native PDA. This clearly confirms the role of GSH in the degradation of PDA. There are some new strong peaks observed at 600<m/z<900 in the mass spectrum of GSH-treated PDA, indicating that Although it is not an easy task to precisely derive the configurations/structures for these oligomer fragments, it is possible to make reasonable predictions for some of the fragments based on the previous studies concerning PDA polymerization12 and the present results of both 13C solid-state NMR spectra (Figure 4) and mass spectra. It was reported that GSH might bind with PDA because of high adhesion of PDA to -SH group in GSH.56 This binding mode is also identified in the present study. As illustrated in Figure S5 and Figure 6, the peaks at m/z 721 and 765 may be attributed to the formation of nanocomposites between GSH and oligomer fragments. As an illustration (Figure 7), the new strong peaks close to m/z values of 393 and 548 may indicate the reduction of -COOH to CH2-OH by GSH.

Figure 6.

The mass spectra of native PDA and that after treatment with 10 mmol L−1 GSH for 72 h.

Figure 7.

The new strong peaks at m/z values of 393 and 548 indicate the reduction of -COOH to CH2-OH in the presence of GSH.

Considering the strong metal-binding affinity of GSH, it is necessary to reveal whether it is bonded to the metallic elements in CuCo2S4 or causes collapse of the inorganic skeleton in the drug release process. After treatment with 10 mmol L−1 GSH for 72 h, XRD pattern of CuCo2S4 in Figure S1B shows no change. This demonstrates that GSH triggers the release of the drug via PDA degradation, but causes no influence on the configuration of CuCo2S4.

This observation well suggests the degradation of PDA, which further disrupts π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions between PDA and DOX, thus promoting the release of DOX. On account of the fact that GSH involved PDA-drug interaction has never been clarified, the mechanisms of GSH initiated drug release response from PDA and PDA-based nanocarriers need further exploitation.

The demonstration of intracellular GSH triggered DOX release.

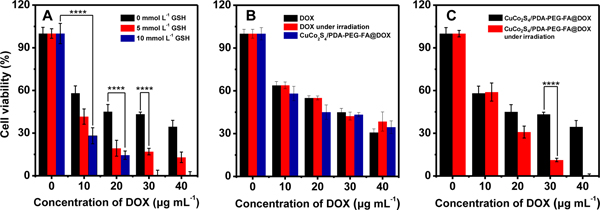

To demonstrate the intracellular triggering effect of GSH on DOX release in the tumor cells, 5 and 10 mmol L−1 of GSH were added into the cultural medium to improve its intracellular concentration level in HeLa cells. The results show that the viability of cells without DOX is not affected by GSH as illustrated in Figure 8A.

Figure 8.

The performance of intracellular GSH triggered DOX release from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX on the treatment of HeLa cells. The concentrations of GSH for HeLa cell incubation are 0, 5 and 10 mmol L−1 (A); The cytotoxicity of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX and free DOX on the treatment of HeLa cells. The power density of NIR is 0.8 W cm−2 (B); The photothermo-chemotherapy performance of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX on the treatment of HeLa cells at near infrared irradiation. The power density of NIR is 0.8 W cm−2 (C). In the above cases, 150 μg mL−1 CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA are used for the treatment of HeLa cells.

In the presence of DOX, either free DOX or CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (corresponding to free DOX concentrations of 10, 20, 30 and 40 μg mL−1), sharply reduced viabilities for the GSH-treated cells are observed with (50% inhibitory concentration) IC50 values of 16, 7, and 7 μg mL−1 (DOX concentration), respectively. The similar IC50 values of 7 μg mL−1 indicate that DOX release can reach a maximum at 5 mmol L−1 of GSH in HeLa cells. The similar results were achieved for the untreated cells at identical experimental conditions. The observations herein clearly indicate the effectiveness of GSH stimulus on triggering the release of DOX from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX in the interior of cancer cells.

The combined photothermo-chemotherapy.

The cytotoxicity of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA nanocarrier was evaluated by measuring the viability of HeLa cells with MTT assays. The results indicate a viability of >80% for HeLa cells (2.5×104 per well) by incubating with 200 μg mL−1 of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA for 24 h (Figure S6). Thus, for further studies, a dosage corresponding to < 200 μg mL−1 of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA was used in the cytotoxicity assay and photothermo-chemotherapy experiments.

The viabilities of HeLa cells (2.5×104 per well) treated with free DOX and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX are compared in Figure 8B. At various equivalent DOX levels corresponding to 10, 20, 30 and 40 μg mL−1, comparable cell viabilities of 58.1, 45.1, 43.3, 34.5% are achieved by incubating with CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX with respect to those by free DOX, e.g., 63.8, 55.0, 45.0 and 37.8%. These results well demonstrate that, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA as a promising drug nanocarrier and delivery vehicle, have a good bio-compatibility.

The photothermo-chemotherapy performance of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX was evaluated by treating on HeLa cells (2.5×104) with NIR irradiation at 808 nm, and the results are illustrated in Figure 8C. In the absence of DOX, no therapeutic effect was observed even with NIR irradiation. However, in the presence of DOX, the photothermo-chemotherapy effect of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX was distinctively evidenced to exhibit significantly higher cytotoxicity, and the increase of DOX dosage gives rise to obvious enhancement on the therapeutic effect. It was worth mentioning that CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX results in a most significant therapeutic performance due to the combined photothermo-chemotherapy effect. CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX exhibits more higher cytotoxicity under NIR irradiation than that not under NIR irradiation with IC The effect of NIR irradiation is twofold: on one hand, it causes thermal ablation of the cancer cells for photothermal therapy; On the other hand, the heat generated by CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites may increase the cell membrane permeability to enhance the cellular uptake. 46

These results demonstrate the feasibility CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX nanocomposites as a photothermo-chemotherapeutic agent for cancer therapy.

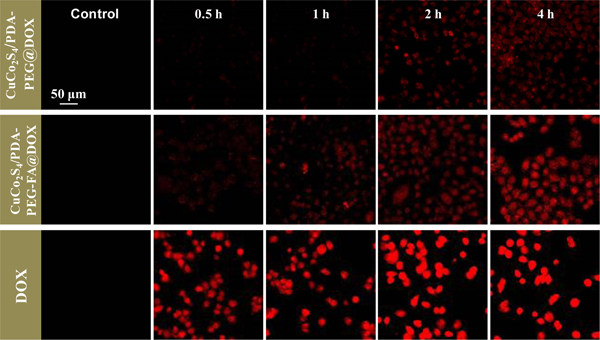

Cellular uptake and cell imaging.

After incubation of the HeLa cells with free DOX, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG@DOX and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX, respectively, for different time intervals, their internalization in the HeLa cells was qualitatively investigated by fluorescence confocal microscopy. It can be seen from Figure 9 that intracellular fluorescence intensity of DOX increases gradually as a function of incubation time, suggesting the time-dependent uptake of free DOX and DOX-containing nanocarriers. The fluorescence intensity of DOX from CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX is obviously stronger than that obtained for CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG@DOX, confirming that FA can enhance the endocytosis through the specific interactions with folate receptors overexpressed on HeLa cell membranes.57–59 To further confirm the effect of FA, HeLa cells were pre-treated with free FA for 2h and then incubated with CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX under identical conditions (as illustrated in Figure S7). It is seen that after FA incubation the fluorescence intensity of DOX is significantly weaker with respect to that by incubation with CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX. On the other hand, the fluorescence intensity of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX is weaker than that achieved for equivalent amount of free DOX. This illustrates that the encapsulation of DOX into the nanocarrier helps to alleviate the damage to normal cells caused by drug leakage, which effectively reduces the intracellular side effects of the drug.

Figure 9.

Fluorescence images of HeLa cells recorded at different time intervals after treated with DOX, CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG@DOX and CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA@DOX (The amount of the materials correspond to a concentration of 50 μg mL−1 DOX in all the cases).

It is well known that the CuCo2S4 nanoparticles exhibit a great potential to serve as MRI contrast agent due to the fact that Co2+ and Co3+ normally possess unpaired 3d electrons.18 Figure 10A illustrates the phantom images of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA aqueous dispersions and proton T1 relaxation measurements at various cobalt concentrations. The T1-weighted MRI of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA shows a concentration-dependent brightening effect. The corresponding longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA is calculated to be 0.905 mM−1 s−1, obtained from the slope of the reciprocal of T1 (r1 = 1/T1) at different concentration levels of cobalt. The r1 value herein is lower than that of CuCo2S4 nanoparticles, 1.02 mM−1 s−1, as reported in the literature 18 because of the coating of PDA. As shown in Figure 10B, the liver region is brightened after injection of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA, and the signal intensities increase gradually as a function of time. This result also confirms that CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA can be used as a potential MRI contrast agent.

Figure 10.

1/T1 value of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA as a function of the concentration of cobalt. Inset: in vitro T1-weighted MRI of the CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA with different aqueous dispersion concentrations, i.e., 0 – 4.49×10−3 mmol L−1 (A); T1-weighted MRI of the liver region after injection of CuCo2S4/PDA-PEG-FA with different time intervals (at a dosage of 4 mg Co/kg) (B).

Conclusions

In conclusion, here we demonstrated a new method for drug delivery based on PDA-coated magnetic CuCo2S4 core-shell nanostructure by GSH triggering degradation of PDA. In the system, the PDA coated CuCo2S4 works as the nanocarriers while folic acid functions as targeting molecules to ensure the safe delivery of DOX to the cancer cells. The controlled release could be enhanced by taking the advantage of PDA pH sensitivity to the acidic tumors. The targeting and treatment on HeLa cancer cells were very effective and the killing was more efficient at higher levels of GSH. Furthermore, the system designed not only can be used for drug delivery but also could combine photothermal therapy with chemotherapy as well as for imaging guided therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (21575020, 21675019, 21727811), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N170505002). W. C. would like to acknowledge the support from the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (USAMRAA) under Contracts of W81XWH-10-1-0279 and W81XWH-10-1-0234 as well as the partial support from NIH/NCI 1R15CA199020-01A1

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare

Notes and references

- 1.Cheng L; Wang C; Feng LZ; Yang K; Liu Z Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (21), 10869–10939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altice CK; Banegas MP; Yabroff KR Tucker-Seeley RD; JNCI, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109 (2), djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traverso N; Ricciarelli R; Nitti M; Marengo B; Furfaro AL; Pronzato MA; Marinari UM; and Domenicotti C Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity, 2013, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han L; Hao YN; Wei X; Chen XW; Shu Y; Wang JH ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3 (12), 3230–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y; Han L; Hu LL; Chang YQ; He RH; Chen ML; Shu Y; Wang JH J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4 (30), 5178–5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang KK; Liu YJ; Liu Y; Zhang Q; Kong CC; Yi CL; Zhou ZJ; Wang ZT; Zhang GF; Zhang Y; Khashab NM; Chen XY; Nie ZH J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (13), 4666–4677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbas M; Zou QL; Li SK; Yan XH Adv. Mater. 2017, 29 (12),1605021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang ZJ; Wang J; Chen CH Adv. Mater. 2013, 25 (28), 3869–3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokoyama M Drug Delivery 2010, 7 (2), 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danhier F; Feron O; Préat VJ Controlled Release 2010, 148 (2), 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenpei F; Bryant Y; Peng H; Xiao Y Ch.; Chem. Rev. 2017, 117(22): 13566–136381. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattni BS; Chupin VV; Torchilin VP Chem. Rev. 2015, 115 (19), 10938–10966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myerson JW; Braender B; McPherson O; Glassman PM; Kiseleva RY; Shuvaev VV; Marcos-Contreras O; Grady ME; Lee HS; Greineder CF; Stan RV; Composto RJ; Eckmann DM; Muzykantov VR Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (32). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv SX; Wu YC; Cai KM; He H; Li YJ; Lan M; Chen XS; Cheng JJ; Yin LC J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (4), 1235–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai N; Yasuoka K; Zeng XC ACS Nano 2016, 10 (8), 8026–8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen MC; Sonaje K; Chen KJ; Sung HW Biomaterials 2011, 32 (36), 9826–9838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallo J; Long NJ; Aboagye EO Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (19), 7816–7833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding CF; Zhong H; Zhang SS Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23 (8), 1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Jian, Ai Lisha, Liu Xin, Hang Hao, Li Yuebin, Zhang Minguang, Zhao Qianru, Wang Xingguo, Chen Wei and Gu Haoshuang. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curcio A; Silva AK; Cabana S; Espinosa A; Baptiste B; Menguy N; Wilhelm C; Abou-Hassan A Theranostics, 2019, 9(5), 1288–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Q; Xu Y; Hu B; An L; Lin J; Tian Q; Yang S (1) Cheng L; Wang C; Feng LZ; Yang K; Liu Z Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (21), 10869–10939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goel S; Chen F; Cai WB Small 2014, 10 (4), 631–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui JB; Jiang R; Xu SY; Hu GF; Wang LY Small 2015, 11 (33), 4183–4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B; Wang Q; Zou RJ; Liu XJ; Xu KB; Li WY; Hu JQ Nanoscale 2014, 6 (6), 3274–3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang SH; Sun CX; Zeng JF; Sun Q; Wang GL; Wang Y; Wu Y; Dou SX; Gao MY; Li Z Adv. Mater. 2016, 28 (40), 8927–8936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu YK; Lin YG; Chen YC Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46 (11), 2117–2119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsaleh N M, Shoko E, Schwingenschlögl U. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2019, 21(2). 662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang X; Zhang S; Ren F; Chen L; Zeng JF; Zhu M; Cheng ZX; Gao MY; Li Z ACS Nano 2017, 11 (6), 5633–5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YK; Cai DD; Wu HX; Fu Y; Cao Y; Zhang YJ; Wu DM; Tian QW; Yang SP Nanoscale 2018, 10 (9), 4452–4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B; Yuan FK; He GJ; Han XY; Wang X; Qin JB; Guo ZX; Lu XW; Wang Q; Parkin IP; Wu CT Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27 (10): 1606218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon JD; Peles DN The Red and the Black. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43 (11), 1452–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu YL; Ai KL; Lu LH Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (9), 5057–5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan J; Yang LP; Lin MF; Ma J; Lu XH; Lee PS Small 2013, 9 (4), 596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng W; Nie JP; Xu L; Liang CY; Peng Y; Liu G; Wang T; Mei L; Huang LQ; Zeng XW ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (22), 18462–18473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng A; Zhang X; Huang Y; Cai Z; Liu X; Liu J RSC Adv. 2018, 8 (13), 6781–6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z; Chen L; Wang Y; Chen X; Zhang P ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8 (40), 26559–26569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peer D; Karp JM; Hong S; FaroKhzad OC; Margalit R; Langer R Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2 (12), 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y; Ai K; Liu J; Deng M; He Y; Lu L Adv. Mater. 2013, 25 (9), 1353–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gullotti E; Park J; Yeo Y Pharm. Res. 2013, 30 (8), 1956–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poinard B; Neo SZY; Yeo ELL; Heng HPS; Neoh KG; Kah JCY ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (25), 21125–21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang XL; Jing F; Lin BL; Cui S; Tu RT; Shen XD; Wang TW ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (17), 15001–15011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu YL; Ai KL; Ji XY; Askhatova D; Du R; Lu LH; Shi JJ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (2), 856–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim K-Y; Yang E; Lee M-Y; Chae K-J; Kim C-M; Kim IS Water Res. 2014, 54, 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chai S; Kan S; Sun R; Zhou R; Sun Y; Chen W; Yu B Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 7607–7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim SH; In I; Park SY Biomacromolecules 2017, 18 (6), 1825–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Oliveira Freitas LB; Gonzalez Bravo IJ; de Almeida Macedo WA; Barros de Sousa EM J Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2016, 77 (1), 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen KJ; Liang HF; Chen HL; Wang YC; Cheng PY; Liu HL; Xia YN; Sung HW ACS Nano 2013, 7 (1), 438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Jamal KT; Al-Jamal WT; Wang JTW; Rubio N; Buddle J; Gathercole D; Zloh M; Kostarelos K ACS Nano 2013, 7 (3), 1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong XY; Yang K; Dong ZL; Yi X; Wang Y; Ge CC; Zhao YL; Liu Z Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25 (47), 7327–7336. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laberge R-M; Karwatsky J; Lincoln MC; Leimanis ML; Georges E Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 73 (11), 1727–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu LL; Meng J; Zhang DD; Chen ML; Shu Y; Wang JH Talanta 2018, 177, 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandra N; Wang D D; Zhu Y; Mao C; Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013, 52(43): 11278–11281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alfieri ML; Micillo R; Panzella L; Crescenzi O; Oscurato SL; Maddalena P; Napolitano A; Ball V; d’Ischia M ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (9), 7670–7680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Della Vecchia NF; Avolio R; Alfe M; Errico ME; Napolitano A; d’Ischia M Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23 (10), 1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang L, Mo S, Liu S G, et al. Sens. Actuators, B. 2018, 259, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hong S; Na YS; Choi S; Song IT; Kim WY; Lee H Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22 (22), 4711–4717. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salmaso S; Semenzato A; Caliceti P; Hoebeke J; Sonvico F; Dubernet C; Couvreur P Bioconjugate Chem. 2004, 15 (5), 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu DM; Wu L; Suo M; Gao S; Xie W; Zan MH; Liu A; Chen B; Wu WT; Ji LW; Chen LB; Huang HM; Guo SS; Zhang WF; Zhao XZ; Sun ZJ; Liu W Nanoscale 2018, 10 (13), 6014–6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chowdhuri AR; Singh T; Ghosh SK; Sahu SK Carbon Dots Embedded Magnetic Nanoparticles @Chitosan @Metal ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 30 (26), 16573–16583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.