Abstract

Background

Total hip and knee arthroplasties are increasingly performed operations, and routine follow-up places huge demands on orthopedic services. This study investigates the effectiveness, patients’ satisfaction, and cost reduction of Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic (VJRC) follow-up of total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty patients in a university hospital. VJRC is especially valuable when in-person appointments are not advised or feasible such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A total of 1749 patients who were invited for VJRC follow-up for knee or hip arthroplasty from January 2017 to December 2018 were included in this retrospective study. Patients were referred to VJRC after their 6-week postoperative review. Routine VJRC postoperative review was undertaken at 1 and 7 years and then 3-yearly thereafter. We evaluated the VJRC patient response rate, acceptability, and outcome. Patient satisfaction was measured in a subgroup of patients using a satisfaction survey. VJRC costs were calculated compared to face-to-face follow-up.

Results

The VJRC had a 92.05% overall response rate. Only 7.22% required further in-person appointments with only 3% being reviewed by an orthopedic consultant. VJRC resulted in an estimated saving of £42,644 per year at our institution. The patients’ satisfaction survey showed that 89.29% of the patients were either satisfied or very satisfied with VJRC follow-up.

Conclusion

VJRC follow-up for hip and knee arthroplasty patients is an effective alternative to in-person clinic assessment which is accepted by patients, has high patient satisfaction, and can reduce the cost to both health services and patients.

Keywords: virtual clinic, telemedicine, arthroplasty, hip, knee

With an ever-increasing aging population, improved life expectancy, and quality of life expectations, the demand for hip and knee arthroplasty is on the rise [1]. The required follow-up for these operations has placed huge demands on orthopedic services in terms of limited outpatient resources and clinical staff [2].

Randomized trials in other specialties have shown general practitioner–led [3], telephone-led [4], paper-led [5], and nurse-led [6] follow-up as valuable alternatives to surgeon-led follow-up clinics. These options can increase patient’s convenience and satisfaction while reducing cost to the national health services [7]. Virtual fracture clinics whereby patient information is collected remotely and then reviewed by a specialist have shown to be cost-effective [8,9]. National guidelines in the United Kingdom recognize that virtual clinic follow-up may be useful to monitor outcome of hip and knee arthroplasty [2,10,11].

After a successful pilot in our university hospital with encouraging results, we further developed a Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic (VJRC) [12]. The aim of this study is to investigate the reliability, patient’s satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness of the VJRC.

Materials and Methods

All patients who were invited for VJRC follow-up for knee or hip arthroplasty from January 2017 to December 2018 were included in this retrospective study.

(A) VJRC SetUp

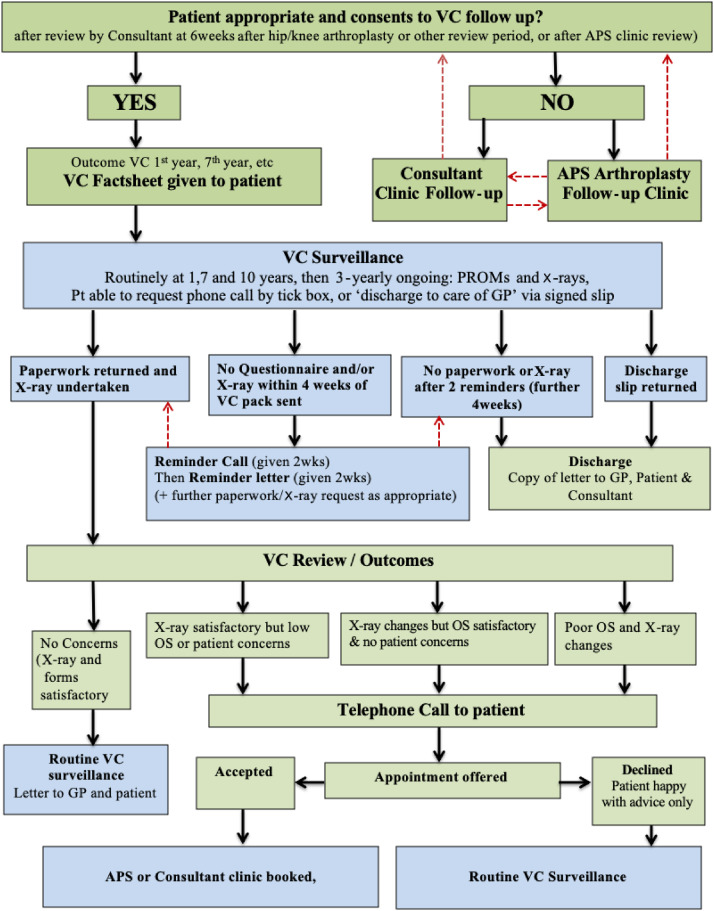

Our standard postoperative follow-up protocol included a face-to-face appointment with the general practitioner or practice nurse at 2 weeks (to have the wound checked and skin clips/sutures removed or trimmed) (Fig. 1 ). Patients then had a face-to-face consultant outpatient clinic appointment (without further imaging) at 6 weeks, as is common practice in the United Kingdom, to ensure and document successful recovery from the procedure or attend to any problems that may have arisen. Patients were all routinely referred to VJRC and invited for the 1-year follow-up if there were no clinical concerns or exclusions. If there were any concerns, the consultant arranged further face-to-face follow-up to the patient and the patient stayed on the in-person follow-up waiting list for long-term follow-up. Patients with early postoperative infection, periprosthetic fracture, complex surgery, novel implants, any clinical concerns, or who expressed wishes to have a face-to-face follow-up were not referred to VJRC. Patients over 75 years of age at the time of surgery with Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP) 10A [10,13] hip implant were discharged from follow-up and not included in VJRC. VJRC follow-up was offered not only to new patients who recently had hip or knee arthroplasties (1-year follow-up) but also to patients who were due to have their year 7 or later long-term follow-up for their joint arthroplasty (legacy patients). Routine VJRC postoperative review following national guidelines [2,10] was undertaken at 1 and 7 years and then 3-yearly thereafter.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the VJRC workflow. VJRC, Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic; VC, virtual clinic; APS, arthroplasty physiotherapy specialist; GP, general practitioner; OS: outcome score.

The patients were sent a VJRC invite pack in the post consisting of an explanatory letter, an addressed prepaid return envelope, patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) booklet, and detailed information to attend a local radiology facility for radiographs of the relevant joint(s). PROMs included a relevant hip or knee Oxford [14], EQ-5D-3L [15], University of California at Los Angeles [16] scores and patient opinions of their joint arthroplasty. Patients were able to book their own radiograph appointment at a convenient time at the radiology facility closest to their home. A reminder call or letter was sent to patients if the completed paperwork and/or plain radiographs were not received after 4 weeks of VJRC invitation. The named consultant was informed if the patient was discharged for any reason.

An arthroplasty physiotherapy specialist (APS) reviewed the information provided (including PROMs) and the requested plain radiographs. All radiographs were further reviewed by an orthopedic consultant. Patients with worsening symptoms, significant decrease in Oxford score since previous review [17], or significant radiological changes had telephone review by the APS. A face-to-face outpatient appointment for further assessment was offered where appropriate, or at patient’s request, either with the APS or with their orthopedic consultant. Patients with revision joint arthroplasty or with significant radiographic changes were normally reviewed by the orthopedic consultant.

(B) Assessment of VJRC

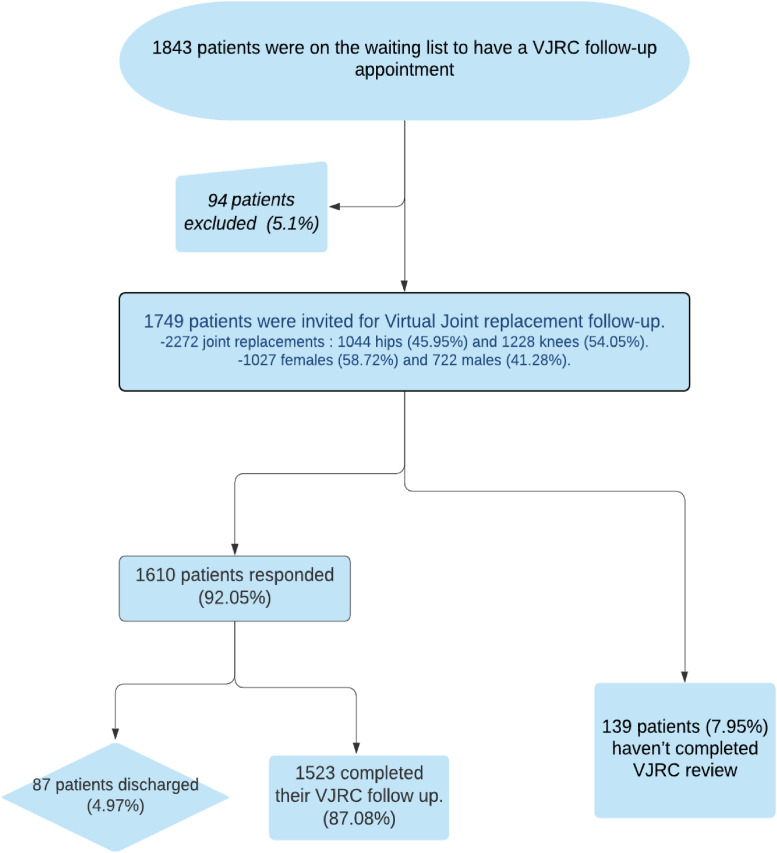

Patient engagement with the VJRC was evaluated by the response rate for all patients invited for VJRC review. A total of 1843 patients who were on the waiting list to have a VJRC follow-up appointment between January 2017 and December 2018 were analyzed. Ninety-four patients (5.1%) were excluded (Table 1 ). We invited 1749 patients, 2272 joint arthroplasties: 1044 hip (45.95%) and 1228 knee (54.05%), to have a VJRC follow-up. The mean age of the patients was 71 years (range, 25-98). There were 1027 female (58.72%) and 722 male (41.28%) patients. The outcome following VJRC was assessed in terms of need for further review or surgery.

Table 1.

Different Reasons for Patients’ Exclusion From VJRC Follow-Up.

| Patient moved out of area. |

| Patient deceased. |

| Nursing home residents with advanced dementia and minimum mobility. |

| Routine review postponed due to medical reasons. |

| Patient under consultant review as referred back by GP. |

| Patient requested formal outpatient appointment instead of VC. |

VJRC, Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic; GP, general practitioner; VC, virtual clinic.

A patient satisfaction survey (Appendix 1) was sent to a subgroup of VJRC patients reviewed over a 1-month period. All patients who were due to have their VJRC follow-up in October 2018 were included in the satisfaction survey. This month was selected as an average representative month, avoiding national holidays and vacations. Patients were asked to comment if they thought that VJRC follow-up helped them in saving time, traveling, or cost. Eighty-six patients were eligible to participate but 10 patients (12%) were excluded as they had moved out of area, deceased, declined use of their data, or postponed their VJRC follow-up. Seventy-six patients were sent the satisfaction questionnaire with a 74% response rate (56 patients).

The overall cost of the VJRC review follow-up process was calculated by our hospital Business Finance Department and compared to the cost of a general orthopedic clinic routine outpatient appointment. The direct and indirect costs were determined for all the resources required including medical, physiotherapy, nursing and other staff time, radiography, estate costs, administrative costs, and other overheads for both VJRC and a general orthopedic clinic routine outpatient appointment. Indirect cost for VJRC patients who subsequently need a face-to-face clinic review appointment was also estimated and added to the total cost of the VJRC. Indirect costs for the patients including transportation costs and time off work were not included as it was not found feasible to accurately estimate. It is important to point out that this was the average cost for a general orthopedic clinic routine outpatient appointment and not a specific cost estimate for an arthroplasty clinic appointment.

Results

Response Rate and Acceptability

The VJRC had a 92.05% overall response rate from invited patients (1610 of 1749), and 139 (7.95%) did not return forms and/or attend X-ray (Fig. 2 ). Eighty-seven patients (4.97%) were discharged postinvite for reasons listed in Table 1. Finally, 1523 patients (87.07%) completed the outcome forms and radiographs. A reminder message was needed in 401 (25%) patients.

Fig. 2.

Flow of participants through the study.

Outcome following VJRC

Out of 1523 VJRC patients, 283 (18.58%) requested or had score or radiological changes requiring a telephone consultation with the APS to discuss their symptoms and/or radiograph results. One hundred ten patients (7.22%) subsequently had a face-to-face outpatient review: 64 patients (4.2%) with the APS and 46 patients (3.02%) with a consultant. Three patients (0.2%) were listed for a revision procedure through their VJRC follow-up. Two patients (0.13%) required revision surgery for aseptic loosening and 1 patient (0.07%) for a broken femoral stem, all with minimal symptoms.

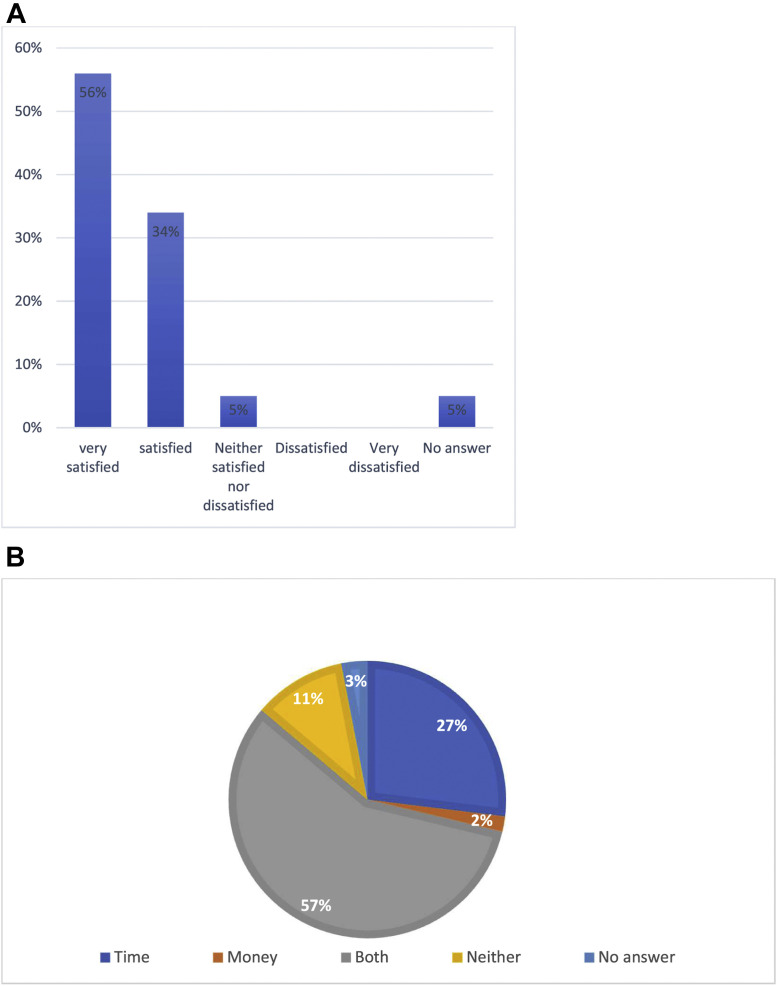

Satisfaction Survey

About 89.29% of patients (50/56) reported were either satisfied or very satisfied with their experience of VJRC, with no patients dissatisfied (Fig. 3 A). And 86% of patients (48/56) found that VJRC saved them time and/or money compared to their previous standard face-to-face outpatient appointment (Fig. 3B). Travel and transport issues were the main reasons given for time and cost savings (Fig. 3C). Only 8% of patients stated a preference for web-based follow-up.

Fig. 3.

(A) Patient satisfaction with their experience of VJRC. “Overall, how satisfied are you with the Virtual Clinic Service?” (B) Patient assessment of VJRC convenience. “Do you feel the Virtual Clinic saved you time and/or money compared to a standard appointment in Orthopedic Outpatients?” (C) Reasons for time and/or cost savings with VJRC perceived by patients. (D) Patients preferred method of future review. “What would be your preferred method of future routine review?” OPA, outpatient appointment.

Cost Reduction

The average VJRC process appointment was found to cost £79 while an average face-to-face process orthopedic outpatient follow-up appointment costed £135, resulting in an estimated saving of £42,644 per year at our institution as shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Cost Analysis and Cost Reduction for VJRC vs Orthopedic Outpatient Appointment.

| Resources/staff | Cost (British pounds) | Resources/staff | Cost (British pounds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Estimate of VJRC Appointment | Cost Estimate of a General Orthopedic Clinic Routine Outpatient Appointment | ||

| APS teleclinic | 18.59 | Orthopedic consultant | 25 |

| APS administration | 7.20 | Nursing/healthcare assistants | 10 |

| Administration team | 5.19 | Physiotherapy | 11 |

| Consultant (X-ray review in approximately 2 min) | 2.86 | Laboratory services | 8 |

| Plain radiographs | 25 | Plain radiographs | 25 |

| Corporate overheads | 14.70 | Medications | 2 |

| Indirect cost estimate of patients who subsequently need a face-to-face clinic review appointment | 5.47 | Outpatient and estate costs | 25 |

| Corporate overheads | 23 | ||

| Others (including secondary commissioning and interest payments) | 6 | ||

| Total cost per appointment | 79 | Total cost per appointment | 135 |

| Estimated total cost for VJRC appointments for the 1523 patients | 120,317 | Estimated cost if these 1523 patients had a face-to-face orthopedic outpatient follow-up | 205,605 |

| Total estimated savings of VJRC | 85,288 (42,644/y) | ||

Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic; APS, arthroplasty physiotherapy specialist.

Discussion

Increasing demand for total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty with associated follow-up has placed huge demands on orthopedic services [7], and a more efficient and acceptable method to monitor arthroplasty patients is required. Previous studies have shown that patients completing questionnaires in their own time are less likely to omit information than during a perceived rushed consultation [18] and that questions asked by an interviewer can lead to a preferred rather than a factual answer owing to the patient’s embarrassment [19]. The concept of virtual clinics has been established for some time, although often related to trauma or fracture clinics [8]. Kingsbury et al [7] found that a questionnaire and radiograph-based remote review, of 599 patients, identified all patients in need of increased surveillance, with good agreement for ongoing patient management and may represent a feasible total joint arthroplasty follow-up mechanism.

The VJRC response rate of 92% is higher than in other studies, with reported rates ranging from 76% to 83% [20,21]. A web-based follow-up study showed that 24% of their eligible patients declined to participate in the virtual follow-up due to lack of internet access. They suggested that computer access may present a technological barrier for older people as the mean age of the patients who declined participation was 74 years [21]. We used paper PROM questionnaires that were sent to the patients by post rather than electronically, which were acceptable to our patient population (mean age = 71 years) and may be a reason for the high VJRC response rate. Only 8% of patients surveyed stated a preference for web-based follow-up.

One of the concerns about reviewing arthroplasty patients remotely is the failure to identify patients who might require revision or subsequent surgical intervention. Marsh et al [22] stated that the causes for subsequent revision were not missed in their study using a web-based follow-up, and Kingsbury et al [7] identified all patients in need of increased surveillance. We also believe that meticulous assessment of PROMs, plain radiographs reviewed by a surgeon together with providing the option to have further in-person appointments to the patients can make this issue to be very unlikely to occur. We had 3 patients who were identified and referred for revision surgery through their VJRC follow-up and are not aware of any “missed” patients.

About 89% of responders were either very satisfied or satisfied regarding their VJRC experience. Marsh et al [21] found that patients who completed the in-person follow-up reported greater levels of satisfaction, but their results still showed a moderate to high satisfaction levels with a web-based virtual follow-up assessment, with a small difference in the satisfaction levels they felt did not outweigh the additional cost-saving and time-saving benefits of the web-based follow-up method. Another study reported that 14% of the eligible patients approached declined to participate, as they preferred to see their surgeon in person, and patients who attended a nonvirtual clinic had higher overall rates of satisfaction [22].

It must be recognized that people value the personal interaction of face-to-face appointments [23]. In developing such virtual follow-up systems, clear pathways of communication are essential, especially when a problem or concern is identified. These findings align with the intention of virtual clinics to provide cost-effective follow-up and face-to-face capacity for those patients who need it. In our study, 18.6% of the patients followed up through virtual clinic had some concerns and needed a telephone call by the APS to discuss things further and to assess the need for a face-to-face outpatient clinic review.

Moreover, 86% of our VJRC patients reported they had experienced time and/or cost savings. This was in accordance with previous studies which reported that the use of virtual clinics resulted in reduction in travel time spent by the patients [15,20].

Virtual follow-up clinics have been reported to be cost-effective compared to standard in-person follow-up [7,12,24], reducing the number of patients attending regular follow-up clinics, without compromising safe practice [20]. Kingsbury et al [7] estimated that an experienced orthopedic surgeon could review a questionnaire and a radiograph in 2 minutes whereas an outpatient appointment can take from 10 to 20 minutes. Hence, upward of 5-10 patients could be reviewed in the time taken to review 1 patient under the current system. Our VJRC managed to massively reduce our in-person outpatient follow-up for joint arthroplasty. Only 7.2% of this cohort required further in-person appointments with very few patients (3%) being reviewed by an orthopedic consultant.

We had an estimated saving of £42,644 per year for our institution. Other studies included virtual arthroplasty follow-up undertaken by an orthopedic surgeon [7,22,25], whereas in our VJRC the orthopedic consultant only reviewed the plain radiographs saving expensive consultant time. In the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, physicians are paid by an annual salary and not on a fee-for-service basis.

UK National Joint Registry data show that we performed 1261 primary hip and knee arthroplasty surgeries in 2016 and 2017 in our institution (727 hip and 534 knee). Following national guidelines [10], hip arthroplasty patients aged over 75 years at the time of surgery were discharged, after satisfactory 6-week postoperative review, and not put forward for VJRC review. Also, 820 primary hip and knee arthroplasty patients had their 1-year follow-up through VJRC in 2017 and 2018. Only 5.0% of patients were discharged postinvite for reasons listed in Table 1 and we do not believe there has been selection bias in this study.

Limitations of this study are that it was a retrospective cohort study and the VJRC was not directly compared to an in-person outpatient follow-up. The satisfaction survey used was not formally validated but was created by a panel including the arthroplasty consultants and arthroplasty physiotherapy specialist running the VJRC. All the points and questions included were agreed upon and found to cover the different aspects and possible benefits and drawbacks of the VJRC. As far as we know, there are no previously validated surveys available at present to assess the satisfaction with virtual clinic and telemedicine follow-up in arthroplasty. To the best of our knowledge, this patient series is the largest in the literature assessing VJRC follow-up for hip and knee arthroplasty.

Virtual clinics have been found to be a very useful tool for follow-up in different subspecialties during the unprecedented difficult times of the COVID-19 pandemic [26]. All routine outpatient clinics were canceled and replaced by virtual and telephone clinics, when appropriate, as they were regarded to be safer for both patients and staff in order to reduce the risk of unnecessary contact. Our VJRC has been able to function, reducing patient contact, during this period. It is likely that virtual clinics and telemedicine will have a bigger role in the follow-up of patients in the future with time and cost savings for both health providers and patients. VJRC is especially valuable when in-person appointments are not advised or feasible such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

VJRC follow-up for hip and knee arthroplasty patients is an effective alternative to in-person clinic assessment which is accepted by patients, has high patient satisfaction, and can reduce the cost to both health services and patients.

Footnotes

No author associated with this paper has disclosed any potential or pertinent conflicts which may be perceived to have impending conflict with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.08.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Appendix

Appendix 1.

VJRC Patients’ Satisfaction Survey.

| ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| ||||||

| I was satisfied with the outcome of the telephone call: | ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| ||||||

| I was satisfied with the outcome at the Orthopedic Outpatient Appointment following further assessment of the joint replacements(s): | ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| The appointment was with: | ||||||

| An orthopedic surgeon | A specialist physiotherapist | |||||

| ||||||||

| Time | Money | Both | Neither | |||||

| If yes, please tick all reasons that apply: | ||||||||

| Travel distance | Travel time | Travel costs | Parking costs | Caregiver time | ||||

| Time off work | Less wait time in clinic | Other (please give details)………………………………………………… | ||||||

| ||||||||

| Very satisfied | Satisfied | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Very dissatisfied | ||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

VJRC, Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic; GP, general practitioner.

References

- 1.Lovelock T., O'Brien M., Young I., Broughton N. Two and a half years on: data and experiences establishing a 'Virtual Clinic' for joint replacement follow up. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:707. doi: 10.1111/ans.14752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Orthopaedic Association . 2012. Primary total hip replacement: A guide to good practice. https://tinyurl.com/yxp9huso. [accessed 11.07.20] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grunfeld E., Mant D., Yudkin P., Adewuyi-Dalton R., Cole D., Stewart J. Routine follow up of breast cancer in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ. 1996;313:665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7058.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallaize R.C., Tinline-Purvis C., Dixon A.R., Pullyblank A.M. Telephone follow-up following office anorectal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:464. doi: 10.1308/003588408X300975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porrett T.R., Lunniss P.J. 'Paper Clinics'- a model for improving delivery of outpatient colorectal services. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:268. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koinberg I.L., Fridlund B., Engholm G.B., Holmberg L. Nurse-led follow-up on demand or by a physician after breast cancer surgery: a randomised study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kingsbury S.R., Dube B., Thomas C.M., Conaghan P.G., Stone M.H. Is a questionnaire and radiograph-based follow-up model for patients with primary hip and knee arthroplasty a viable alternative to traditional regular outpatient follow-up clinic? Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:201. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B2.36424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins P.J., Morton A., Anderson G., Van Der Meer R.B., Rymaszewski L.A. Fracture clinic redesign reduces the cost of outpatient orthopaedic trauma care. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5:33. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.52.2000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holgate J., Kirmani S., Anand B. Virtual fracture clinic delivers British Orthopaedic Association compliance. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:51. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.British Hip Society , British Orthopaedic Association, Royal College of Surgeons of England . 2017. Commissioning guide: Pain arising from the hip in adults. https://tinyurl.com/y2dyjwv3. [accessed 11.07.20] [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Association of knee Surgery, British Orthopaedic Association, Royal College of Surgeons of England . 2017. Commissioning guide: Painful osteoarthritis of the knee. https://tinyurl.com/y2dyjwv3. [accessed 11.07.20] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batten T., Murphy N., Keenan J. Developing and implementing a virtual clinic for follow-up of major joint arthroplasty in the NHS. Br J Health Care Manag. 2017;23:362. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orthopaedic data evaluation panel. www.odep.org.uk [accessed 02.06.20]

- 14.Murray D.W., Fitzpatrick R., Rogers K., Pandit H., Beard D.J., Carr A.J. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1010. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim J., Hamilton D.F. Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS-10 Global Health and EQ-5D questionnaires in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-b:832. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B7.BJJ-2018-1543.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naal F.D., Impellizzeri F.M., Leunig M. Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:958. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beard D.J., Harris K., Dawson J., Doll H., Murray D.W., Carr A.J. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:73. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaver K., Williamson S., Chalmers K. Telephone follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: views and experiences of patients and specialist breast care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood G., Naudie D., MacDonald S., McCalden R., Bourne R. An electronic clinic for arthroplasty follow-up: a pilot study. Can J Surg. 2011;54:381. doi: 10.1503/cjs.028510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher R., Khatun F., Reader S., Hamilton V., Porteous M., Dunn A. 0040 - virtual knee arthroplasty clinic; 5 Year follow up data in A district general hospital. Knee. 2017;24:XI. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsh J., Bryant D., MacDonald S.J., Naudie D., Remtulla A., McCalden R. Are patients satisfied with a web-based followup after total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1972. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3514-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh J.D., Bryant D.M., MacDonald S.J., Naudie D.D., McCalden R.W., Howard J.L. Feasibility, effectiveness and costs associated with a web-based follow-up assessment following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1723. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkes R.J., Palmer J., Wingham J., Williams D.H. Is virtual clinic follow-up of hip and knee joint replacement acceptable to patients and clinicians? A sequential mixed methods evaluation. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000502. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh J., Hoch J.S., Bryant D., MacDonald S.J., Naudie D., McCalden R. Economic evaluation of web-based compared with in-person follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:1910. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharareh B., Schwarzkopf R. Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:918. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohannessian R., Duong T.A., Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e18810. doi: 10.2196/18810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.