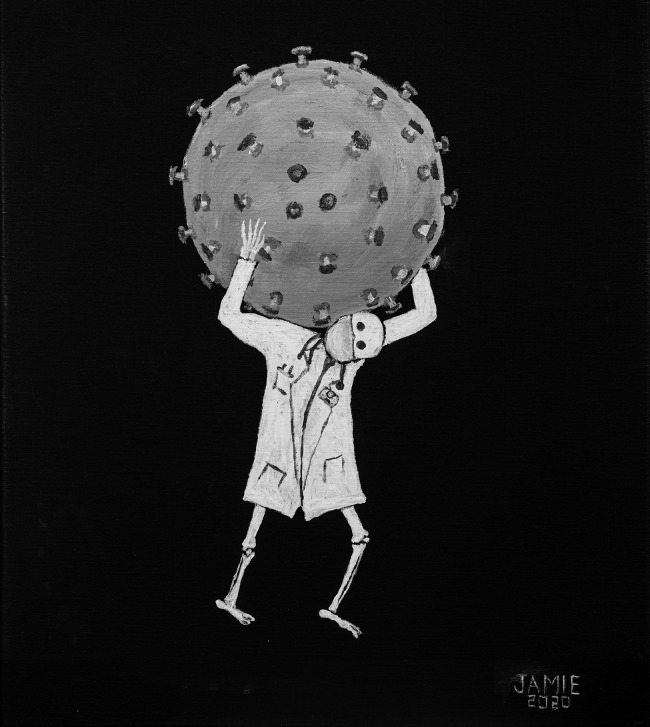

The hospital leadership team was anxiously discussing the potential rate of personal protective equipment usage, and the likelihood of an N95 mask shortage. I had started carrying a pocket-sized journal to capture not only details I needed to keep straight in the rapidly changing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) landscape, but also a place to sketch and jot down ideas. I had previously drawn and painted an image of the earth transformed into a giant coronavirus virion, the planet covered in COVID-19. As the meeting went on, way past its appointed time, I drew an outline of Atlas carrying a globe, with a viral substitution for his usual burden. I thought about how pandemics have shaped our world, from the Plague of Athens to the Black Death. When it came time to get out my acrylics after a long week in the hospital, the concept had evolved into the painting that accompanies this editorial (Figure ).

Figure.

Atlas Covidicus, acrylic painting by Jamie Newman, 2020.

In Greek mythology, Atlas, who was a Titan, fought on the losing side in the battle against Zeus and the other gods of Olympus. In the inventive way of divine punishment—which sentenced his fellow Titan, Prometheus, to having an eagle consume his ever-regenerating liver—Atlas was doomed to shoulder the weight of the celestial globe, a burden that is frequently depicted instead as the planet Earth. Over the centuries, this image of Atlas with the globe has come to mean the stoic bearing of a heavy load—like the load physicians and healthcare staff currently bear in navigating COVID-19.

In the case of the human body, the Atlas is the name for the first cervical vertebra, which supports or bears the weight of the skull. Osseous imagery is often used to represent death, whether skulls or skeletons. Skeletons are prominent in famous paintings, whether depicted by the cowled Grim Reaper, ready to wield its deadly scythe, or the army of skeletons that dominate The Triumph of Death by Bruegel the Elder. Skeletons can also have a more upbeat symbolism. Paintings or statues of and for the Mexican holiday El Día de los Muertos often depict festive skeletons as, for example, a mariachi band or a couple at a wedding. Whether gruesome or entertaining, the skeleton is imbued with a worldwide cultural significance.

Nowadays, nothing could symbolize the modern physician more than the white coat and stethoscope. This was not always the case, however; in the nineteenth century it might have been more common to see the likeness of a doctor in a top hat and black coat, carrying a cane. With the advent of antisepsis, and the invention of the stethoscope by Laënnec, the symbolic representation has evolved. Now we may add to this image the increasingly and essential presence of the face mask and scrub suit.

As a whole, then, this painting depicts the struggle of the physician and the looming presence of mortality, as a result of the heavy coronal burden we bear. We are living in a time of pandemic-induced societal upheaval. Coronavirus disease 2019 is a huge weight, and our collective shoulders must carry this heavy viral load. Turning to the humanities, whatever the medium, can help us process and cope with these monumental challenges, so we can continue with the essential work ahead.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: The author is solely responsible for the content of this manuscript.