Abstract

Objective

Neurosurgery departments worldwide have been forced to restructure their training programs because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In this study, we describe the impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgical training in Southeast Asia.

Methods

We conducted an online survey among neurosurgery residents in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand from May 22 to 31, 2020 using Google Forms. The 33-item questionnaire collected data on elective and emergency neurosurgical operations, ongoing learning activities, and health worker safety.

Results

A total of 298 of 470 neurosurgery residents completed the survey, equivalent to a 63% response rate. The decrease in elective neurosurgical operations in Indonesia and in the Philippines (median, 100% for both) was significantly greater compared with other countries (P < 0.001). For emergency operations, trainees in Indonesia and Malaysia had a significantly greater reduction in their caseload (median, 80% and 70%, respectively) compared with trainees in Singapore and Thailand (median, 20% and 50%, respectively; P < 0.001). Neurosurgery residents were most concerned about the decrease in their hands-on surgical experience, uncertainty in their career advancement, and occupational safety in the workplace. Most of the residents (n = 221, 74%) believed that the COVID-19 crisis will have a negative impact on their neurosurgical training overall.

Conclusions

An effective national strategy to control COVID-19 is crucial to sustain neurosurgical training and to provide essential neurosurgical services. Training programs in Southeast Asia should consider developing online learning modules and setting up simulation laboratories to allow trainees to systematically acquire knowledge and develop practical skills during these challenging times.

Key words: COVID-19, Global neurosurgery, Neurosurgery education, Neurosurgery training, Southeast Asia

Abbreviations and Acronyms: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, Personal protective equipment

Introduction

Worldwide, the practice of neurosurgery has not been immune to the disruption in health care systems caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: elective surgeries have been cancelled, outpatient clinics closed, international meetings postponed, and in many areas, neurosurgeons called on to augment the workforce of clinical departments that cared for patients with COVID-19.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Several letters to the editor and research articles have previously enumerated changes in neurosurgical education in North America, Europe, and Africa.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 These data are lacking for Southeast Asian countries.

In this study, we aimed to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical training in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Although there is no unified neurosurgical training program in the region, the 5 countries share similar program structures, strengths and weaknesses, and cultural norms in neurosurgical education.17 Geographic proximity and existing socioeconomic ties also make collaborative effort during the recovery period feasible. The results of the current study are vital to address present and future challenges to neurosurgical education arising from this global health crisis.

Methods

From May 22 to 31, 2020, we conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study among neurosurgery residents in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, using a Web-based, self-administered survey on Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, California, USA). The Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health ethics board granted ethical approval for the study.

The last author (R.B.) drafted the survey questionnaire based on previously published studies on COVID-19 and neurosurgical practice.7 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 The co-authors, who are consultant neurosurgeons involved in neurosurgical training in their respective countries, vetted the questions and revised items as necessary. The final survey instrument consisted of 33 questions (Appendix A) and took 5 minutes to complete.

The following data were collected: country of origin; residency training information (name of institution and year level); changes in neurosurgical department activities because of COVID-19 (emergency and elective surgeries, outpatient clinics, conferences, and research activities); ongoing educational activities and availability of resources to support online learning; as well as information relevant to health worker safety (availability of personal protective equipment [PPE] and COVID-19 testing). Two open-ended questions at the end of the survey probed for the greatest concerns of the trainees and their planned strategies to bridge gaps in skills and knowledge during the pandemic period.

We distributed the survey link (http://tinyurl.com/covidsea) to the different training programs of the 5 Southeast Asian countries using personal communications and online methods (e.g., e-mail, Twitter, and messaging applications such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Line, and Viber). Only neurosurgery residents in the region were included in the survey. Post-residency fellows and international trainees performing clinical rotations were excluded.

Data were de-identified and exported to Stata/IC version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA) for analysis. Invalid and duplicate entries were removed. Descriptive statistics were calculated, reporting frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean, median, and range for continuous variables. Data were stratified by country and training level. A χ2 or Fisher exact test was used to evaluate relationships between categorical variables. A Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to determine if there were any significant differences in the reduction of neurosurgical procedures among subgroups, followed by post hoc Mann-Whitney tests for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments, as necessary. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Survey Response Rate

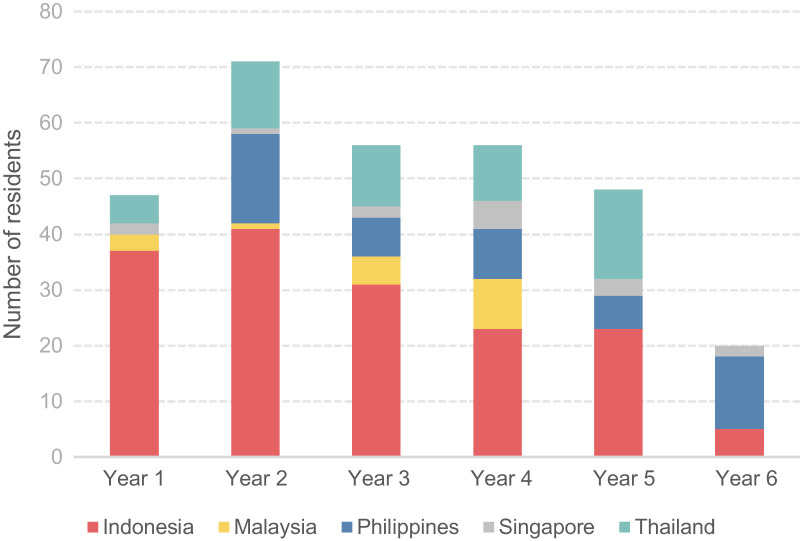

We received 324 responses. We removed 21 that were duplicates based on provided e-mail addresses and 5 that were invalid. Thus, 298 responses were included in the data analysis. This result represented 63% of the estimated 470 neurosurgical trainees in the region (Table 1 and Figure 1 ). All 33 training programs had at least 2 respondents in the survey. There were 63 chief residents (21%), defined as residents in their final year of training. Most of the respondents (n = 260, 87%) worked in a hospital that treated both patients with COVID and patients who did not have COVID (i.e., hybrid hospital).

Table 1.

Comparison of Neurosurgical Workforce and Survey Participation Among Five Southeast Asian Countries

| Country | World Bank Income Group | Number of Neurosurgeons∗ | Neurosurgeon/Population Ratio† | Number of Training Programs | Duration of Training (years) | Estimated Number of Trainees∗ | Number of Respondents (Percentage of Trainees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | Lower middle income | 377 | ∼1 in 718,000 | 8 | 5.5 | 211 | 160 (76) |

| Malaysia | Upper middle income | 152 | ∼1 in 210,000 | 2 | 4 | 53 | 18 (35) |

| Philippines | Lower middle income | 134 | ∼1 in 807,000 | 10 | 6 | 57 | 51 (89) |

| Singapore | High income | 65 | ∼1 in 88,000 | 2 | 6 | 20 | 15 (75) |

| Thailand | Upper middle income | 536 | ∼1 in 130,000 | 11 | 5 | 129 | 54 (42) |

Figures obtained by study authors through personal communications with their respective neurosurgical societies.

Based on World Bank 2019 population data.20

Figure 1.

The number of survey respondents in each country, stratified by year level in training. Duration of neurosurgery training is 4 years in Malaysia, 5 years in Thailand, 5.5 years in Indonesia, and 6 years in the Philippines and Singapore.

Elective and Emergency Neurosurgical Operations

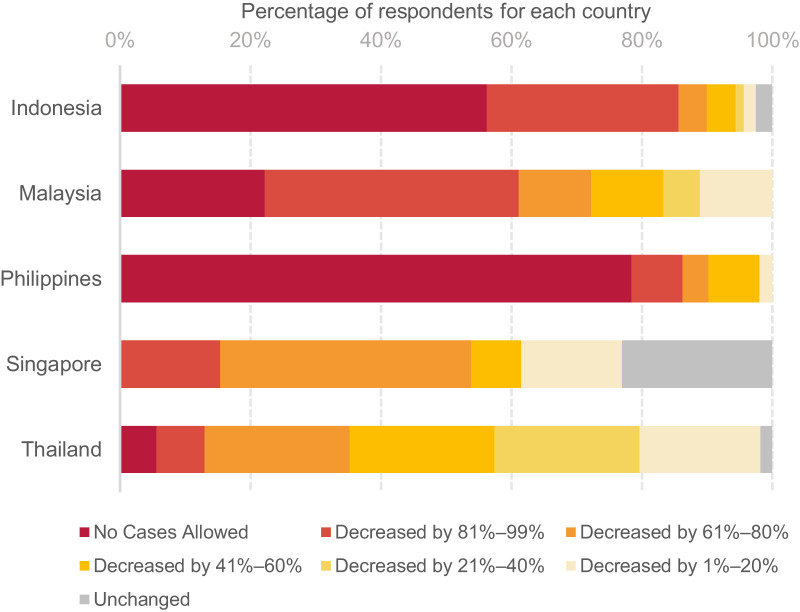

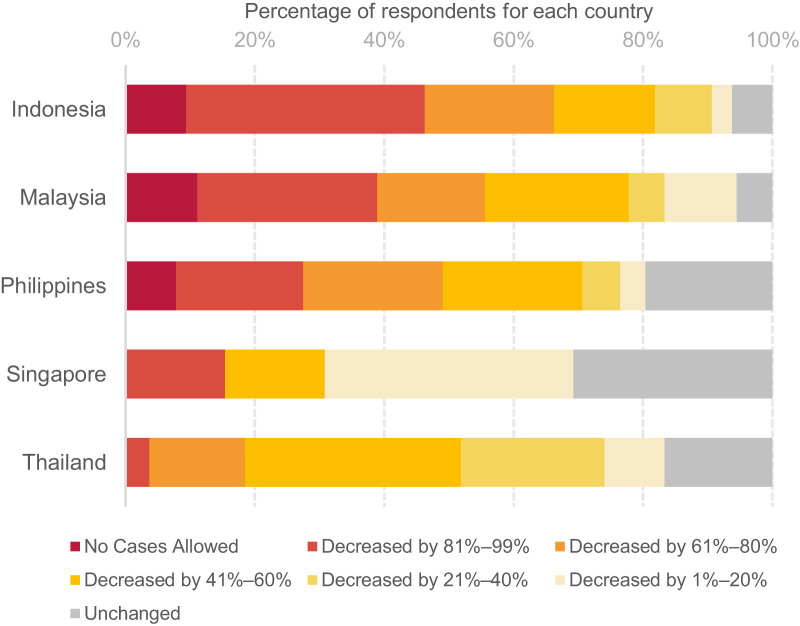

Figures 2 and 3 show the reported decrease in elective and emergency neurosurgical procedures performed by neurosurgical trainees in the 5 countries. At the time of the survey, median reduction in elective procedures ranged from 50% in Thailand to 100% in Indonesia and the Philippines (Table 2 ). Statistical analyses showed that there was a significantly greater reduction in elective cases in Indonesia and the Philippines (i.e., fewer surgeries performed) compared with any of the other countries (P < 0.001). For emergency cases, median reduction in neurosurgical operations ranged from 20% in Singapore to 80% in Indonesia. Trainees in Indonesia and Malaysia performed significantly fewer emergency procedures compared with trainees in Singapore or Thailand (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

In the survey questionnaire, we asked the respondents, “How many percent of elective neurosurgical operations are you doing now?” (i.e., May 22–31, 2020 compared with 3 months before the pandemic). This graph shows the frequency of responses in each Southeast Asian country, stratified from 100% reduction (i.e., no elective cases were allowed) to 0% reduction (i.e., no change in the number of elective cases). Red and orange bars represent a greater reduction in the number of cases.

Figure 3.

In the survey questionnaire, we asked the respondents, “How many percent of emergency neurosurgical operations are you doing now?” (i.e., May 22–31, 2020 compared with 3 months before the pandemic). This graph shows the frequency of responses in each Southeast Asian country, stratified from 100% reduction (i.e., no emergency cases were allowed) to 0% reduction (i.e., no change in the number of emergency cases). Red and orange bars represent a greater reduction in the number of cases.

Table 2.

Comparison of Reduction in Neurosurgical Operations Performed by Neurosurgical Trainees in Five Southeast Asian Countries

| Indonesia (n = 160) | Malaysia (n = 18) | Philippines (n = 51) | Singapore (n = 13∗) | Thailand (n = 54) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent reduction in elective neurosurgical operations | Mean ± SD | 90 ± 22 | 79 ± 28 | 94 ± 16 | 52 ± 37 | 52 ± 27 | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 100 (8) | 92.5 (39) | 100 (0) | 70 (60) | 50 (40) | ||

| Percent reduction in emergency neurosurgical operations | Mean ± SD | 71 ± 29 | 65 ± 31 | 57 ± 35 | 30 ± 33 | 41 ± 25 | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 80 (45) | 70 (40) | 60 (62) | 20 (50) | 50 (40) |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

2 residents were excluded because they were on research rotation.

We investigated if year level in training influenced the decrease in surgical exposure (Table 3 ). The reduction of elective neurosurgical procedures was similar for chief residents and the rest of the trainees (median, 96% and 98%, respectively; P = 0.621). Likewise, no significant difference was observed for the reduction in emergency neurosurgical procedures (median, 50% and 70%, respectively; P = 0.237).

Table 3.

Comparison of Responses of Chief Residents (i.e., Residents in Final Year) and the Rest of the Neurosurgical Trainees

| Chief Residents (n = 63) | Rest of the Trainees (n = 235) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent reduction in elective neurosurgical operations | Mean ± SD | 79 ± 29 | 82 ± 28 | 0.621 |

| Median (IQR) | 96 (40) | 98 (20) | ||

| Percent reduction in emergency neurosurgical operations | Mean ± SD | 56 ± 35 | 62 ± 32 | 0.237 |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (55) | 70 (50) | ||

| “Do you feel that the COVID-19 pandemic will have a significant negative impact on your training overall?” | Yes, n (%) | 42 (67) | 179 (76) | 0.299 |

| No, n (%) | 7 (11) | 20 (9) | ||

| Not sure, n (%) | 14 (22) | 36 (15) |

No significant differences were observed in the reported reduction of elective and emergency neurosurgical operations, as well as in the perceived impact of the pandemic on their training. SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

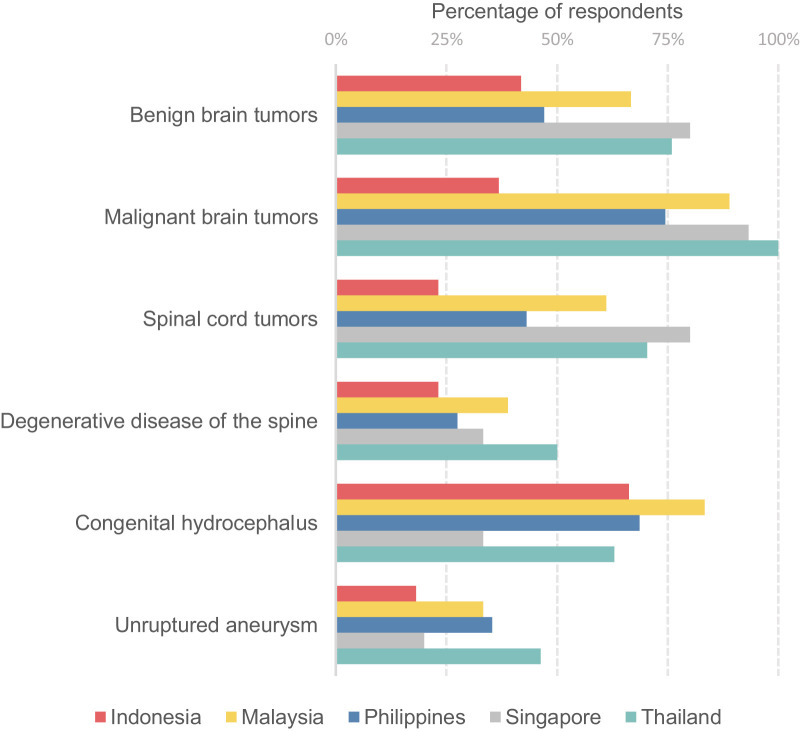

The respondents were asked to select elective neurosurgical procedures that they were allowed to perform in their hospitals during the study period. The results for 6 neurosurgical conditions (benign brain tumor, malignant brain tumor, spinal cord tumor, degenerative disease of the spine, congenital hydrocephalus, and unruptured aneurysm) are presented in Figure 4 . A higher percentage of trainees in Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore continued to perform surgeries for the first 4 indications.

Figure 4.

We asked the respondents to select neurosurgical procedures that they were allowed to perform in their training centers at the time of the survey (May 24–31, 2020). This graph shows the percentage of respondents in each country for 6 neurosurgical conditions. During the pandemic, a higher percentage of neurosurgery residents from Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore continued to perform surgeries for brain tumors, spinal cord tumors, and degenerative diseases of the spine.

Other Educational Activities

One third of the respondents indicated that their outpatient clinics had closed, with a median duration of 8 weeks. Most affected were trainees in the Philippines (76%). In contrast, only 16% of trainees from Indonesia reported clinic closures. Telemedicine clinics were most used in Indonesia (69%) and Thailand (76%).

Whereas 98 (33%) noted a decrease in their research productivity, 42 residents (14%) had an increase in research work. In Thailand, 54% of trainees had no change in their research activities. Overall, 213 residents (71%) said that they would miss at least 1 opportunity for international education and training because of the pandemic. These opportunities included elective rotations or observership programs (n = 129, 43%), conference presentations (n = 90, 30%), and clinical fellowship positions (n = 44, 15%).

Online Learning Activities and Resources

Most neurosurgical departments had modified morbidity and mortality conferences and grand rounds from face-to-face to virtual meetings. The trainees reported adequate access to technological resources. Most owned a smartphone (n = 287, 96%) or a laptop computer (n = 267, 90%), and they connected to the Internet primarily using mobile data (n = 274, 92%). However, many (n = 139, 47%) did not use an online learning platform (e.g., Google Classroom, Canvas, or Moodle). In Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, mentors initiated learning activities. The opposite was true for Singapore and Thailand, where learning activities were more likely to be initiated by trainees. International webinars were most popular among the Indonesian residents, 91% of whom reported watching online lectures twice a week or more. Among the Thai trainees, 68% said that they attended webinars only once a month or less. Only 6% of the trainees reported having access to a neurosurgical simulation laboratory.

COVID Work and Health Worker Safety

At some point, 107 of the respondents (36%) had been deployed to COVID-19 units of their hospitals such as wards, intensive care units, and acute respiratory infection clinics. Although all Singaporean trainees indicated that they were provided with adequate and appropriate PPE in the workplace, 43% and 41% of respondents from Indonesia and the Philippines, respectively, said that the PPE in their hospital was either inappropriate or inadequate in supply. Testing for COVID-19 was widely available among all training institutions but not routine. Most (n = 231, 78%) said that their hospitals tested only health workers with symptoms or exposure to COVID-19.

Concerns of Trainees

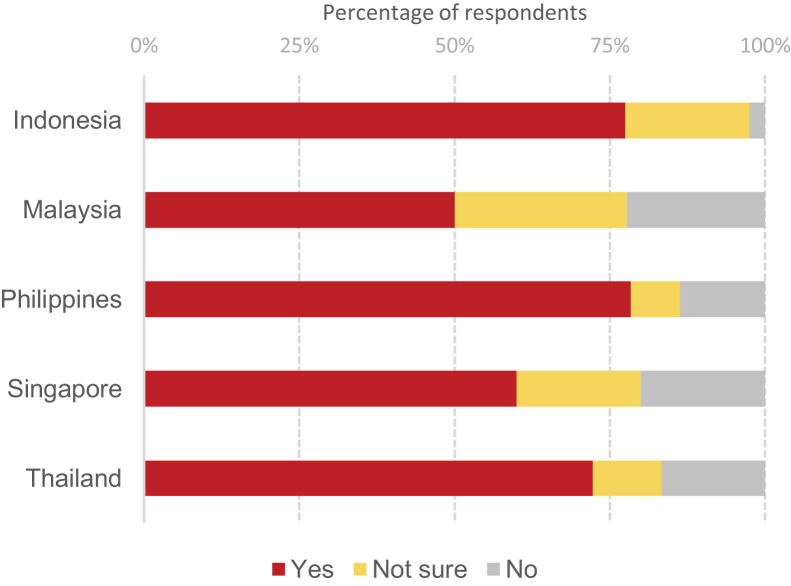

Most of the trainees (n = 221, 74%) believed that the COVID-19 crisis will have a negative impact on their overall neurosurgical training (Figure 5 ). There was no significant difference in the opinions of the chief residents compared with the rest of the trainees (67% vs. 76%; P = 0.299; Table 3). Analysis of the free-text responses showed that the residents were most concerned about the following: 1) marked decrease in their hands-on surgical experience, 2) uncertainty about their board examination and potential delay in career advancement, 3) increasing number of backlog cases, 4) risk of acquiring COVID-19 in the workplace, and 5) risk of transmitting COVID-19 to their families.

Figure 5.

We asked the respondents, “Do you feel that the COVID-19 pandemic will have a significant negative impact on your training overall?” This graphs shows the percentage of responses (yes, not sure, and no) for each Southeast Asian country.

Detailed survey results with frequencies and percentages for each country are available in Appendix B.

Discussion

Our findings confirm that COVID-19 has affected all aspects of neurosurgical training in Southeast Asia. The extent of the impact varied among the 5 countries included in this study. Significantly higher reductions in neurosurgical operations were observed in Indonesia and the Philippines. These effects were less evident in Singapore and Thailand, where a higher percentage of trainees continued to perform key neurosurgical procedures. Malaysian trainees also had a marked decrease in emergency operations, but their capacity to perform elective procedures was higher compared with colleagues in Indonesia and the Philippines.

Most of the trainees worked in hybrid hospitals that managed both patients with COVID and patients without COVID. Thus, it was usually not necessary to transfer patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 when they required neurosurgical care. This situation was particularly true in Singapore and Thailand. On the other hand, in Indonesia and the Philippines, when the aforementioned patients were initially admitted in non-COVID hospitals, they were immediately transferred to COVID centers. At their discretion, neurosurgeons in the Philippines could opt to perform emergency procedures in non-COVID hospitals, but full PPE was required for staff. The approach was slightly different in Malaysia. Dedicated COVID centers cancelled all elective and emergency surgeries at the height of the pandemic. Neurosurgical patients were then diverted to non-COVID hospitals. Emergency procedures were allowed in hybrid hospitals, but COVID-19 testing was mandatory for all patients and full precautions were undertaken during the surgery.

It is worthwhile to examine these differences in the context of the countries’ existing health care systems and national strategies to control COVID-19 transmission.20, 21, 22 Indonesia and the Philippines are lower-middle-income countries with the lowest neurosurgeon/population ratios. At the other end of the spectrum, Singapore is a high-income country, with the highest density of neurosurgeons. Thailand and Malaysia are upper-middle-income countries, with neurosurgeon/population ratios closer to the benchmark commonly set at 1:100,000.23

These 5 countries were at different stages of the pandemic at the time of the survey (Table 4 ).22 , 24, 25, 26, 27 Singapore had documented the highest number of COVID-19 cases. However, it also had the lowest number of deaths and performed the highest number of tests per thousand people. Although the number of new COVID-19 cases in Thailand and Malaysia had steadily decreased, the numbers of infections and deaths in the Philippines and Indonesia still continued to increase during the study period. Case fatality rates and recovery rates in Indonesia and the Philippines were also worse compared with their Southeast Asian neighbors.

Table 4.

COVID-19 Situation in Five Southeast Asian Countries During the Study Period

| Indonesia | Malaysia | Philippines | Singapore | Thailand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population in 2019∗ | 270,625,568 | 31,949,777 | 108,116,615 | 5,703,569 | 69,625,582 |

| Total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases† | 25,773 | 7762 | 17,224 | 34,336 | 3077 |

| Total number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths† | 1573 | 115 | 950 | 23 | 57 |

| Case fatality rate (%) | 6.1 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| Total number of recoveries† | 7015 | 6330 | 3808 | 20,727 | 2961 |

| Case recovery rate (%) | 27 | 82 | 22 | 60 | 96 |

| Total number of COVID-19 tests† | 216,769 | 546,368 | 328,144 | 408,495‡ | 420,000‡ |

All values as of 30 May, 2020, except where indicated. Indonesia and the Philippines have the highest case fatality rate, the lowest recovery rate, and the lowest number of tests per capita for COVID-19 in the region. These are also the countries with the greatest reduction in elective neurosurgical operations, as seen in Table 2.

Data obtained from the World Bank.20

As of June 1, 2020.

The survey results suggest that successful control of COVID-19 infections and deaths at the national level seems to be important in ensuring continuation of neurosurgical training and provision of essential neurosurgical services. This finding is not at all surprising. Good governance is vital in managing the COVID-19 crisis, especially in resource-limited settings. Prioritizing COVID-19 services means allocating mechanical ventilators and intensive care unit beds to their patients, thus leaving fewer resources available to the neurosurgical service of a hospital. There may also be a shortage of human resources, with doctors and operating room nurses being divided into cohorts or deployed to COVID units.12 , 28 It would not be safe to resume or continue neurosurgical services when there is a shortage of PPE, or when patients are not adequately screened and tested for COVID-19.

Several reasons may account for the marked decrease in emergency and elective consults. Because of fear of contracting COVID-19 in health care facilities, people may delay seeking consult, even for urgent neurosurgical conditions.3 , 29 Strict lockdown policies and lack of public transportation have also restricted movement of people across regions; this is important to consider, especially because most neurosurgical centers are located in urban areas and city centers.

It may take some time before outpatient clinics resume normal services, especially if the infrastructure of a hospital does not provide adequate ventilation or allow social distancing among patients and staff. Many neurosurgical departments have shifted to telemedicine and virtual clinics.30 , 31 Doctors must keep in mind that patients, especially from low-income and middle-income countries, may not necessarily have the gadgets or Internet connection to avail themselves of these services, leading to further delays in the provision of care.

When a patient needs neurosurgery, training officers are often confronted with the question, “Who should do the case?”8 , 9 , 12 , 32 Should it be the senior or chief resident, who is expected to take up less time in the operating theater, require no assist and therefore less PPE, and have a lower risk of complications, potentially avoiding a prolonged hospital stay? But what about the junior residents, who also need to learn neurosurgery from hands-on experience, not just from online videos? In Singapore, operations were generally consultant led, to minimize surgical time and patient exposure.

At the start of the pandemic, when testing capacity was low and results took several days to be released, neurosurgical centers in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines treated all patients as if they had COVID-19, following all safety protocols and personnel restrictions as described earlier. These concerns were hardly encountered in Thailand and Singapore, where the capacity to test patients was rapidly increased early on, making it possible to immediately identify patients without COVID who required only the standard of care. As testing capacity increased and turnaround times for results shortened in the other countries, we observed a corresponding increase in cases in which we could safely allow trainees to scrub in. Once again, this finding highlights that an effective response against COVID-19 has a direct positive impact on neurosurgical care.

Neurosurgical trainees in Southeast Asia were most worried about the dramatic decrease in their neurosurgical operations, potentially leading to loss of skills and lack of opportunities to acquire new ones. Many were concerned about their future, and rightly so. They were uncertain if they would be allowed to graduate from training or take the national board examination, considering the strict competency assessment in neurosurgery. No one knows for sure how long the pandemic will last and when neurosurgical services worldwide will return to “normal.” Although a vaccine against the virus is not yet available and herd immunity is questionable, a second or third wave of infections may easily force hospitals to shut down their operating rooms again.

The trainees’ fears could be allayed only by clear guidelines and expectations from the neurosurgical societies of the different countries. Training programs should also address concerns regarding health worker safety, especially the lack of PPE.33 , 34 The constant fear of bringing home the virus to one’s family only adds to the trainees’ physical exhaustion and psychological stress during this time.7 , 35

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative that neurosurgical education continues in this part of the world, where there remains a large deficit in the neurosurgical workforce.36 To increase surgical volumes, 1 strategy has been to improve the neurosurgical capacity of regional and secondary hospitals, designated as non-COVID centers. For instance, in Malaysia, several neurosurgeons and trainees have been reassigned to these hospitals, where they provide general neurosurgical services. On the other hand, consultant neurosurgeons in Indonesia have increased the involvement of trainees in cases performed in private hospitals. In Philippine General Hospital, the largest COVID referral center in the Philippines, an ad hoc committee that prioritized surgical cases based on specified criteria such as prognosis and expected length of postoperative hospital stay has allowed gradual resumption of elective neurosurgical procedures.

Potential areas for growth in the region include the development of online training modules or virtual boot camps for neurosurgery residents, augmented by simulation laboratories that would allow learners to develop practical skills. Such modules may be standardized across training programs in a country, perhaps even shared with international colleagues. Program directors need not start from scratch; instead, the use of free, readily available, and curated online resources such as the Neurosurgical Atlas and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons’ Nexus.37 Although caseload remains low, training programs should also consider setting up simulation laboratories that would allow trainees to obtain hands-on experience, without risk of acquiring COVID-19. The learning experience could be enhanced further with current advances in virtual and augmented reality.38

The rapid publication of COVID-19 guidelines and experiences relevant to neurosurgery has allowed wide dissemination of best practices globally.4 , 39, 40, 41, 42 Online webinars have been instrumental in bridging the gaps in knowledge during this pandemic. Such video lectures could be improved further by adding subtitles and making language translations available. We can only hope that these newfound virtual connections would translate to in-person collaborations when borders reopen, especially because many young neurosurgeons in the region have lost opportunities for global education and training.

Our study is limited by selection bias, wherein neurosurgical trainees who have been most affected by COVID-19 may not have had time to answer our survey. The reported decreases in elective and emergency neurosurgical procedures may have also been subject to self-reporting bias. Hospital policies on allowable operations are dynamic, and we have presented data only for a specific time window. When possible, a review of the residents’ operation logs several months after the study period would provide a more objective means to quantify the impact of COVID-19 on the trainees’ surgical volumes. It would be ideal to obtain the perspective of the program directors and consultant neurosurgeons in the region, to determine whether they concur with the perceived impact of the pandemic on training. The long-term effects of the pandemic on the mental health of trainees, including burnout rates, also merit further investigation.

Conclusions

Neurosurgery residents in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand face ongoing challenges in their training because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Trainees were most concerned about the decrease in their hands-on surgical experience, uncertainty in their career advancement, and occupational safety in their workplace. An effective national strategy to control COVID-19 is crucial to sustain neurosurgical training and to provide essential neurosurgical services. Training programs in the region should consider developing online learning modules and setting up simulation laboratories, which would allow trainees to systematically acquire knowledge and develop practical skills. It is important to make contingency plans for another pandemic, to ensure minimal disruption of neurosurgical education in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nunthasiri Wittayanakorn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Vincent Diong Weng Nga: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Mirna Sobana: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Nor Faizal Ahmad Bahuri: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Ronnie E. Baticulon: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. John Carlo B. Reyes for assisting us in the statistical analyses; and the Academy of Filipino Neurosurgeons, the Philippine Association of Neurosurgical Residents, the Pediatric Neurosurgical Commission of Indonesian Society of Neurological Surgeons (PERSPEBSI), the Royal College of Neurological Surgeons of Thailand, and all training programs in Southeast Asia for supporting this study. We are especially grateful to the neurosurgery residents who answered our online survey despite challenging circumstances. The full list of training programs that participated is in Appendix C.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that the article content was composed in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

R.E.B. presented the preliminary data of the study during the first global neurosurgery webinar organized by the Global Neurosurgery Committee and Young Neurosurgeons Committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies on 13 June, 2020.

Appendix A: Survey Instrument

This is a survey on the impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgical training and education in Southeast Asia. The survey is open to all neurosurgical residents in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore. The entire survey will only take 5 minutes to complete. If you are NOT from any of these countries, there is no need to answer the survey.

Participation in this survey is voluntary. By answering the survey, you consent to providing your personal information to the study investigators. The researchers will maintain the confidentiality of data and all data will be de-identified prior to analysis. Training hospitals will de-identified as well in the final paper.

For questions, you may e-mail Dr. Nunthasiri Wittayanakorn at nanthasiriw@gmail.com.

Thank you in advance for your participation.

Nunthasiri Wittayanakorn, MD (Thailand)

Vincent Diong Weng Nga, MBBS (Singapore)

Mirna Sobana, MD (Indonesia)

Nor Faizal Ahmad Bahuri, MBBS, MSurg, DPhil (Malaysia)

Ronnie E. Baticulon, MD (Philippines)

∗Required questions

Informed Consent∗

I have read the study description above and AGREE to participate in the survey.

I do NOT wish to participate in the survey.

-

1.

What is your e-mail address?∗

-

2.Which country are you from?∗

- Indonesia

- Malaysia

- Philippines

- Singapore

- Thailand

Neurosurgical Training

-

3.Are you a neurosurgery resident in training?∗

- Yes

- No

-

4.Select your training program from the list.∗

- (Dropdown list of training programs)

-

5.Which level are you in your neurosurgery training program?∗

- Year 1

- Year 2

- Year 3

- Year 4

- Year 5

- Year 6 or higher

-

6.Are you in your final year of training?∗

- Yes

- No

Tell Us About the Impact of COVID-19 on Your Training

-

7.Does your training hospital treat COVID-19 patients?

- Yes - only COVID patients are being admitted (dedicated COVID hospital)

- Yes - but non-COVID patients are still being admitted (hybrid COVID hospital)

- No

- Not sure

-

8.Does your hospital perform neurosurgical operations on patients with probable or confirmed COVID-19?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

-

9.Which of these were cancelled in your training hospital? Pick all that apply. Leave the boxes unchecked if your hospital was NOT affected.

- Emergency surgeries

- Elective surgeries

- Outpatient clinics

- Face-to-face meetings and conferences

-

10.

If EMERGENCY surgeries were cancelled in your hospital, how many WEEKS were they cancelled?

-

11.

If ELECTIVE surgeries were cancelled in your hospital, how many WEEKS were they cancelled?

-

12.

If OUTPATIENT CLINICS were cancelled in your hospital, how many WEEKS were they cancelled?

-

13.What will happen to your ongoing research projects?

- Proceed as usual

- Decrease in research activity (cancellation, modification, complete stop, less time for research)

- Increase in research activity (additional projects, more progress, more time for research)

- I don’t have any research at present

-

14.Which of the following were you planning to participate in, but are now cancelled because of COVID-19? Pick all that apply.

- Accepted poster or platform presentation in an international conference

- Elective rotation or observership in another neurosurgical center abroad

- Job interview for post-residency fellowship abroad

- Clinical fellowship training

- Research fellowship training

-

15.What will happen to your scheduled neurosurgical examination this year?

- Proceed as scheduled

- Defer to a later date

- No announcement yet

Neurosurgical Operations

EMERGENCY surgery is defined as one that may result to death or significant morbidity if not performed within 24 hours.

-

16.Compared to the last 3 months before the COVID-19 pandemic, how many percent of EMERGENCY neurosurgical operations were you doing during the PEAK of the COVID-19 pandemic in your country?∗

- No change

- Decreased by about 1% to 20%

- Decreased by about 21% to 40%

- Decreased by about 41% to 60%

- Decreased by about 61% to 80%

- Decreased by about 81% to 99%

- No EMERGENCY cases were allowed

-

17.

How many percent of EMERGENCY neurosurgical operations are you doing NOW? Please write a number from 0 to 100.∗

-

18.Compared to the last 3 months before the COVID-19 pandemic, how many percent of ELECTIVE neurosurgical operations were you doing during the PEAK of the COVID-19 pandemic in your country?∗

- No change

- Decreased by about 1 to 20%

- Decreased by about 21 to 40%

- Decreased by about 41 to 60%

- Decreased by about 61 to 80%

- Decreased by about 81 to 99%

- No ELECTIVE cases were allowed

-

19.How many percent of ELECTIVE neurosurgical operations are you doing NOW? Please write a number from 0 to 100.∗

-

20.At present, which of the following neurosurgical conditions are you allowed to treat in your center? Pick all that apply. If none, please leave the boxes blank.

- Benign brain tumors

- Malignant brain tumors

- Congenital hydrocephalus

- Craniosynostosis, encephaloceles, and other congenital anomalies

- Unruptured aneurysm

- Unruptured AVM

- Spinal cord tumors

- Degenerative disease of the spine

- Epilepsy

- Spasticity, movement disorders, or pain

Online Learning in Neurosurgery

-

21.Which alternative learning activities in neurosurgery are ongoing in your hospital? Pick all that apply.

- Telemedicine or virtual clinic

- Virtual morbidity and mortality conference

- Virtual grand rounds and case presentation

- Simulation laboratories

- Research activities

- Mentoring

- Other…

-

22.Which of the following devices do you own? Pick all that apply.

- Smartphone

- iPad or Tablet

- Laptop

- Desktop computer

-

23.How do you access materials for online learning/e-learning? Pick all that apply.

- Personal mobile data

- Personal postpaid internet subscription (e.g., broadband, DSL)

- Hospital network/Wi-Fi

-

24.Who usually starts the learning activities in your department/training program?

- Trainees

- Mentors

- Hospital administrator

- Other…

-

25.Does your institution/training program use a formal e-learning platform to teach neurosurgery? Examples: Schoology, Moodle, Google Classroom, Canvas. Platform should have online materials, quizzes and self-directed learning.

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

-

26.How often do you watch online neurosurgery webinars conducted by international speakers or trainers outside of your center? Examples: Zoom, WebEx, GoToWebinar, GoogleMeet

- Never

- Once a month or less

- Once a week

- Twice a week or more

-

27.The following may be considered barriers to learning during this pandemic period. Which of the following have you experienced? Pick all that apply.

- Limited internet access or lack of learning devices

- Lack of physical spaces conducive to learning

- Busy with hospital work not related to neurosurgery

- Busy with responsibilities at home or to family

- Mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, burnout)

- Lack of basic needs (e.g., food, water, medicine, security)

- No clear instructions from the training program

- Other…

-

28.Do you feel that the COVID-19 pandemic will have a significant NEGATIVE impact on your training overall?∗

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

-

29.

What are your greatest concerns at the moment regarding your neurosurgical training?

-

30.

How do you plan to make up for your missed neurosurgical training activities?

Care for COVID-19 Patients

-

31.Have you ever been assigned to work in a COVID ward, COVID ICU, or Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) clinic?

- Yes

- No

-

32.How would you describe the supply of PPE in your main hospital of work?

- Appropriate and adequate supply

- Inappropriate and/or inadequate supply

- The hospital does not provide PPE

-

33.How does your workplace test COVID-19 for health care workers?

- All health care workers undergo routine testing for COVID-19, even if there are no symptoms

- Only those with symptoms and/or exposure are tested for COVID-19

- COVID-19 testing is not available in my training hospital

[END OF SURVEY]

Appendix B.

Detailed Survey Results by Country

| Indonesia (n = 160) |

Malaysia (n = 18) |

Philippines (n = 51) |

Singapore (n = 15) |

Thailand (n = 54) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Year level | |||||||||||

| 1 | 37 | 23 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 5 | 9 | |

| 2 | 41 | 26 | 1 | 6 | 16 | 31 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 22 | |

| 3 | 31 | 19 | 5 | 28 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 13 | 11 | 20 | |

| 4 | 23 | 14 | 9 | 50 | 9 | 18 | 5 | 33 | 10 | 19 | |

| 5 | 23 | 14 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 20 | 16 | 30 | |||

| ≥6 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 25 | 2 | 13 | |||||

| Place of work | |||||||||||

| Dedicated COVID hospital | 13 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 22 | |

| Hybrid COVID hospital | 146 | 91 | 12 | 67 | 49 | 96 | 14 | 93 | 39 | 72 | |

| Non-COVID | 1 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Cancelled activities | |||||||||||

| Outpatient clinics | 25 | 16 | 10 | 56 | 39 | 76 | 5 | 33 | 18 | 33 | |

| Conferences | 112 | 70 | 14 | 78 | 49 | 96 | 12 | 80 | 37 | 69 | |

| Effect on research projects | |||||||||||

| Proceed as usual | 37 | 23 | 5 | 28 | 14 | 27 | 2 | 13 | 29 | 54 | |

| Increase in research | 14 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 12 | 24 | 4 | 27 | 10 | 19 | |

| Decrease in research | 53 | 33 | 10 | 56 | 18 | 35 | 9 | 60 | 8 | 15 | |

| No ongoing research | 55 | 34 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 13 | |

| Missed opportunities | |||||||||||

| Poster | 46 | 29 | 6 | 33 | 20 | 39 | 7 | 47 | 11 | 20 | |

| Observership | 70 | 44 | 2 | 11 | 15 | 29 | 5 | 33 | 37 | 69 | |

| Job interview | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Research fellowship | 16 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | |

| Clinical fellowship | 32 | 20 | 6 | 33 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2 | |

| Any of the above | 119 | 74 | 12 | 67 | 29 | 57 | 10 | 67 | 43 | 80 | |

| Device ownership | |||||||||||

| Smartphone | 155 | 97 | 18 | 100 | 51 | 100 | 15 | 100 | 48 | 89 | |

| Tablet | 56 | 35 | 8 | 44 | 38 | 75 | 9 | 60 | 42 | 78 | |

| Laptop computer | 150 | 94 | 16 | 89 | 49 | 96 | 14 | 93 | 38 | 70 | |

| Desktop computer | 12 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 4 | 27 | 15 | 28 | |

| Internet access | |||||||||||

| Mobile data | 150 | 94 | 15 | 83 | 48 | 94 | 14 | 93 | 47 | 87 | |

| Postpaid subscription | 56 | 35 | 13 | 72 | 32 | 63 | 11 | 73 | 23 | 43 | |

| Hospital Internet | 64 | 40 | 3 | 17 | 36 | 71 | 11 | 73 | 36 | 67 | |

| Online learning platform available? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 68 | 43 | 10 | 56 | 13 | 25 | 2 | 13 | 24 | 44 | |

| No | 57 | 36 | 8 | 44 | 36 | 71 | 13 | 87 | 25 | 46 | |

| Not sure | 34 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 | |

| Who initiates learning activities? | |||||||||||

| Trainees | 76 | 48 | 8 | 44 | 39 | 76 | 12 | 80 | 47 | 87 | |

| Mentors | 135 | 84 | 13 | 72 | 41 | 80 | 10 | 67 | 33 | 61 | |

| Administrators | 14 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 11 | |

| Ongoing learning activities | |||||||||||

| Telemedicine or virtual clinic | 111 | 69 | 6 | 33 | 30 | 59 | 7 | 47 | 41 | 76 | |

| Virtual morbidity and mortality | 68 | 43 | 2 | 11 | 37 | 73 | 13 | 87 | 31 | 57 | |

| Virtual grand rounds | 124 | 78 | 7 | 39 | 45 | 88 | 10 | 67 | 32 | 59 | |

| Simulation laboratories | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Research activities | 36 | 23 | 1 | 6 | 28 | 55 | 7 | 47 | 21 | 39 | |

| Mentoring | 69 | 43 | 4 | 22 | 17 | 33 | 6 | 40 | 14 | 26 | |

| How often do you watch webinars? | |||||||||||

| Never | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 24 | |

| 1× a month or less | 1 | 1 | 5 | 28 | 12 | 24 | 5 | 33 | 24 | 44 | |

| 1× a week | 13 | 8 | 4 | 22 | 21 | 41 | 6 | 40 | 7 | 13 | |

| 2× a week or more | 146 | 91 | 6 | 33 | 17 | 33 | 4 | 27 | 10 | 19 | |

| Will COVID-19 have a negative impact on your training? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 124 | 78 | 9 | 50 | 40 | 78 | 9 | 60 | 39 | 72 | |

| No | 4 | 3 | 4 | 22 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 20 | 9 | 17 | |

| Not sure | 32 | 20 | 5 | 28 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 20 | 6 | 11 | |

| Have you worked in COVID-19 units? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 42 | 26 | 3 | 17 | 30 | 59 | 3 | 20 | 29 | 54 | |

| No | 117 | 73 | 15 | 83 | 21 | 41 | 11 | 73 | 23 | 43 | |

| Not indicated | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 4 | |

| Describe your hospital's PPE | |||||||||||

| Appropriate and adequate | 81 | 51 | 12 | 67 | 30 | 59 | 15 | 100 | 41 | 76 | |

| Inappropriate and/or inadequate | 68 | 43 | 6 | 33 | 21 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 20 | |

| No PPE available | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not indicated | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Is testing available for health workers? | |||||||||||

| Routine | 45 | 28 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 9 | |

| Only with exposure | 113 | 71 | 16 | 89 | 41 | 80 | 14 | 93 | 47 | 87 | |

| No testing available | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not indicated | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

PPE, personal protective equipment.

Appendix C: List of participating training programs

Indonesia

Diponegoro University, Semarang UNDIP

Hasanuddin University, Sulawesi UNHAS

Padjadjaran University, Bandung UNPAD

Udayana University, Denpasar UNUD

University of Indonesia, Jakarta UI

University of Sumatra Utara, Medan North Sumatra USU

Airlangga University, Surabaya UNAIR

Gajah Mada University, Yogyakarta UGM

Malaysia

Universiti Sains Malaysia

Universiti Malaya

Philippines

Armed Forces of the Philippines Medical Center–V. Luna General Hospital

Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center

Makati Medical Center

Philippine General Hospital

Southern Philippines Integrated Neurosurgical Training Program

St Luke’s Medical Center

The Medical City

University of Santo Tomas Hospital

University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center

Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center

Singapore

National Neuroscience Institute (NNI), Singhealth

National University Health System (NUHS)

Thailand

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital

Chiangmai University Hospital

Chulalongkorn Hospital

Khon Kean University Hospital

Phramongkutklao Hospital

Prasart Neurology Institute

Ramathibodi Hospital

Siriraj Hospital

Songklanagarind Hospital

Thammasart University Hospital

Vachira Hospital

References

- 1.Antony J., James W.T., Neriamparambil A.J., Barot D.D., Withers T. An Australian response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its implications on the practice of neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e864–e871. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontanella M.M., Saraceno G., Lei T. Neurosurgical activity during COVID-19 pandemic: an expert opinion from China, South Korea, Italy, United Stated of America, Colombia and United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0390-5616.20.04994-2 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg Sci. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gilligan J., Gologorsky Y. Collateral damage during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:413–414. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jean W.C., Ironside N.T., Sack K.D., Felbaum D.R., Syed H.R. The impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgeons and the strategy for triaging non-emergent operations: a global neurosurgery study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:1229–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondziolka D., Couldwell W.T., Rutka J.T. Introduction. On pandemics: the impact of COVID-19 on the practice of neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.3.JNS201007 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Spina A., Boari N., Gagliardi F., Bailo M., Calvanese F., Mortini P. Management of neurosurgical patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.161 [e-pub ahead of print]. World Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Alhaj A.K., Al-Saadi T., Mohammad F., Alabri S. Neurosurgery residents’ perspective on COVID-19: knowledge, readiness, and impact of this pandemic. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e848–e858. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bambakidis N.C., Tomei K.L. Editorial. Impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgery resident training and education. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.3.JNS20965 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bray D.P., Stricsek G.P., Malcolm J. Letter: Maintaining neurosurgical resident education and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 2020;368:m1106. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark V.E. Editorial. Impact of COVID-19 on neurosurgery resident research training. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.4.JNS201034 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kanmounye U.S., Esene I.N. COVID-19 and Neurosurgical education in Africa: making lemonade from lemons. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:732–733. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler R.A., Oermann E.K., Dangayach N.S., Bederson J., Mocco J., Shrivastava R.K. Letter to the Editor: changes in neurosurgery resident education during the COVID-19 pandemic: an institutional experience from a global epicenter. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:439–440. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis C.T., Zeineddine H.A., Esquenazi Y. Challenges of neurosurgery education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a U.S. perspective. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:545–547. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low J.C.M., Visagan R., Perera A. Neurosurgical training during COVID-19 pandemic: British perspective. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.178 [e-pub ahead of print]. World Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Pelargos P.E., Chakraborty A., Zhao Y.D., Smith Z.A., Dunn I.F., Bauer A.M. An evaluation of neurosurgical resident education and sentiment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a North American survey. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:e381–e386. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoia C., Raffa G., Somma T. COVID-19 and neurosurgical training and education: an Italian perspective. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;160:1493. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferraris K.P., Matsumura H., Wardhana D.P.W. The state of neurosurgical training and education in East Asia: analysis and strategy development for this frontier of the world. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;48:E7–E8. doi: 10.3171/2019.12.FOCUS19814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalafallah A.M., Jimenez A.E., Lee R.P. Impact of COVID-19 on an Academic neurosurgery department: the Johns Hopkins experience. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e877–e884. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcadio R.L., Ocampo P.D.S., editors. Current Status of Medical Education in the Philippines. National Academy of Science and Technology; Taguig, Philippines: 2005. pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank Total Population. The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL Available at:

- 21.The World Bank World Bank country and lending groups. The World Bank. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Available at:

- 22.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 Available at:

- 23.Kenning T.J. Neurosurgical Workforce Shortage: The Effect of Subspecialization and a Case for Shortening Residency Training–AANS Neurosurgeon. AANS Neurosurgeon. https://aansneurosurgeon.org/departments/neurosurgical-workforce-shortage-effect-subspecialization-cast-shortening-residency-training/ Available at:

- 24.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Total confirmed COVID-19 cases. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/total-cases-covid-19?yScale=log&time=2020-03-01..2020-06-15&country=IDN∼MYS∼PHL∼SGP∼THA Available at:

- 25.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Total confirmed COVID-19 deaths. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/total-deaths-covid-19?time=2020-03-01..2020-06-15&country=IDN∼MYS∼PHL∼SGP∼THA Available at:

- 26.Our World in Data Total COVID-19 tests. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/full-list-total-tests-for-covid-19?time=2020-05-30&country=IDN∼MYS∼PHL∼THA∼Singapore%2C%20samples%20tested Available at: %%%.

- 27.Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries Available at:

- 28.Robertson F.C., Lippa L., Broekman M.L.D. Editorial. Task shifting and task sharing for neurosurgeons amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.4.JNS201056 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Galarza M., Gazzeri R. Letter: Collateral pandemic in face of the present COVID-19 pandemic: a neurosurgical perspective. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E186–E188. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leong A.Z., Lim J.X., Tan C.H. COVID-19 response measures–a Singapore Neurosurgical Academic Medical Centre experience segregated team model to maintain tertiary level neurosurgical care during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2020.1758629 [e-pub ahead of print]. Br J Neurosurg. accessed June 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wright C.H., Wright J., Shammassian B. COVID-19: launching neurosurgery into the era of telehealth in the United States. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:54–55. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber A.C., Henderson F., Santos J.M., Spiotta A.M. Letter: for whom the bell tolls: overcoming the challenges of the COVID pandemic as a residency program. Neurosurgery. 2020;119:e947. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Zhou M., Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:100–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Lancet COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dewan M.C., Rattani A., Fieggen G. Global neurosurgery: the current capacity and deficit in the provision of essential neurosurgical care. Executive Summary of the Global Neurosurgery Initiative at the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.11.JNS171500 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tomlinson S.B., Hendricks B.K., Cohen-Gadol A.A. Editorial. Innovations in neurosurgical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: is it time to reexamine our neurosurgical training models? https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.4.JNS201012 [e-pub ahead of print]. J. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Zaed I., Tinterri B. How is COVID-19 going to affect education in neurosurgery? A step toward a new era of educational training. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:481–483. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.COVIDSurg Collaborative Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11646 [e-pub ahead of print]. Br J Surg. accessed May 30, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Burke J.F., Chan A.K., Mummaneni V. Letter: the coronavirus disease 2019 global pandemic: a neurosurgical treatment algorithm. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E50–E56. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muhammad S., Tanikawa R., Lawton M.T., Niemelä M., Hänggi D. Letter: safety instructions for neurosurgeons during COVID-19 pandemic based on recent knowledge and experience. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E220–E221. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Germanò A., Raffa G., Angileri F.F., Cardali S.M., Tomasello F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Neurosurgery: literature and neurosurgical societies recommendations update. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e812–e817. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]