Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In January 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and in March 2020, COVID-19 was characterized as a global pandemic that is responsible for infecting over 20 million and more than 700,000 deaths. COVID-19 symptoms are fever, cough, fatigue, headache, diarrhea, arthromyalgias, serious interstitial pneumonia that can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis-induced coagulopathy and multi-organ dysfunction [1]. In addition, the severe progression of COVID-19 results in cytokine storm with excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [2]. Previously, outbreaks of similar viruses which belong to the β-coronavirus family occurred in 2002–2004 and 2012–2014, as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), respectively [3,4].

Currently, there is no approved drug treatment or vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Until these become available, one must include adequate and balanced nutrition for proper body functioning and boosting of the immune system. Micronutrients, vitamin C and vitamin D have gained much attention during the pandemic because of their anti-inflammatory and immune-supporting properties. Low levels of vitamins D and C result in coagulopathy and suppress the immune system, causing lymphocytopenia. Evidence has shown that the mortality rate is higher in COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D concentrations. Further, vitamin C supplementation increases the oxygenation index in COVID-19 infected patients [5]. Similarly, vitamin B deficiency can significantly impair cell and immune system function, and lead to inflammation due to hyperhomocysteinemia.

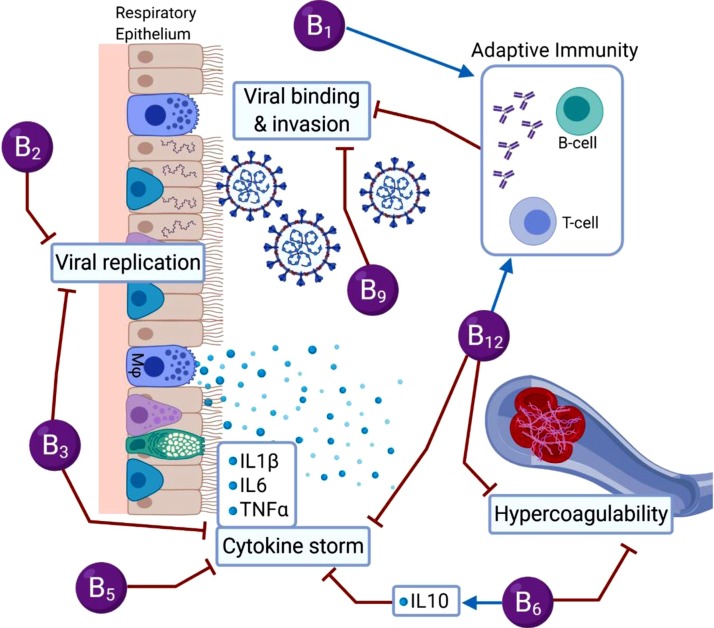

There is a need to highlight the importance of vitamin B because it plays a pivotal role in cell functioning, energy metabolism, and proper immune function [6]. Vitamin B assists in proper activation of both the innate and adaptive immune responses, reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, improves respiratory function, maintains endothelial integrity, prevents hypercoagulability and can reduce the length of stay in hospital [7,8]. Therefore, vitamin B status should be assessed in COVID-19 patients and vitamin B could be used as a non-pharmaceutical adjunct to current treatments (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Summary of the different roles vitamin B can play during COVID-19.

1. Can vitamin B be used to manage COVID-19?

1.1. Vitamin B1 (Thiamine)

Thiamine is able to improve immune system function and has been shown to reduce the risk of type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, aging-related disorders, kidney disease, cancer, mental disorders and neurodegenerative disorders [6]. Thiamine deficiency affects the cardiovascular system, causes neuroinflammation, increases inflammation and leads to aberrant antibody responses [6]. As antibodies, and importantly T-cells, are required to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus, thiamine deficiency can potentially result in inadequate antibody responses, and subsequently more severe symptoms. Hence, adequate thiamine levels are likely to aid in the proper immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, the symptoms of COVID-19 are very similar to altitude sickness and high-altitude pulmonary edema. Acetazolamide is commonly prescribed to prevent high-altitude sickness and pulmonary edema through inhibition of the carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes and subsequently increases oxygen levels. Thiamine also functions as a carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme inhibitor [9]; hence, high-doses of thiamine given to people at early stages of COVID-19 could potentially limit hypoxia and decrease hospitalization. Further research is required to determine whether administration of high thiamine doses could contribute to the treatment of patients with COVID-19.

1.2. Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin)

Riboflavin together with UV light cause irreversible damage to nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA, rendering microbial pathogens unable to replicate. Riboflavin and UV light has been shown to be effective against the MERS-CoV virus, suggesting that it could also be helpful against SARS-CoV-2 [10]. In fact, riboflavin-UV decreased the infectious titer of SARS-CoV-2 below the limit of detection in human blood [10] and in plasma and platelet products [11]. This could alleviate some of the risk of transfusion transmission of COVID-19 and as well as reducing other pathogens in blood products for critically ill COVID-19 patients.

1.3. Vitamin B3 (Nicotinamide, Niacin)

Niacin acts as a building block of NAD and NADP, both vital during chronic systemic inflammation [12]. NAD+ acts as a coenzyme in various metabolic pathways and its increased levels are essential to treat a wide range of pathophysiological conditions. NAD+ is released during the early stages of inflammation and has immunomodulatory properties, known to decrease the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. [[13], [14], [15]]. Recent evidence indicates that targeting IL-6 could help control the inflammatory storm in patients with COVID-19 [16]. Moreover, niacin reduces neutrophil infiltration and exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect in patients with ventilator-induced lung injury. In hamsters, niacin and nicotinamide prevents lung tissue damage [17]. In addition, nicotinamide reduces viral replication (vaccinia virus, human immunodeficiency virus, enteroviruses, hepatitis B virus) and strengthens the body’s defense mechanisms. Taking into account the lung protective and immune strengthening roles of niacin, it could be used as an adjunct treatment for COVID-19 patients [8,18].

1.4. Vitamin B5 (Pantothenic acid)

Pantothenic acid has a number of functions, including cholesterol- and triglyceride-lowering properties, improves wound healing, decreases inflammation and improves mental health [6]. Even though there are limited studies demonstrating the effects of pantothenic acid on the immune system, it is a viable vitamin for future investigation.

1.5. Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, Pyridoxine)

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) is an active form of pyridoxine, and is an essential cofactor in various inflammatory pathways with deficiency leading to immune dysregulation. PLP has an inverse relationship with plasma IL-6 and TNF-α in chronic inflammatory conditions. During inflammation, the utilization of PLP increases results in its depletion, suggesting that COVID-19 patients with high inflammation may have deficiency. Low PLP levels have been noted in patients with type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and in the elderly [[19], [20], [21]], groups who are at higher risk of poorer COVID-19 outcomes. Dysregulation of immune responses and increased risk of coagulopathy have also been noted among COVID-19 patients. In a recent preprint it is suggested that PLP supplementation mitigates COVID-19 symptoms by regulating immune responses, decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, maintaining endothelial integrity and preventing hypercoagulability [22]. In fact, it was shown three decades ago that PLP levels reduce abnormalities in platelet aggregation and blood clot formation [23]. Recently researchers at Victoria University reported that vitamin B6 (as well as B2 and B9) upregulated IL-10, a powerful anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokine which can deactivate macrophages and monocytes and inhibit antigen-presenting cells and T cells [24]. COVID-19 patients often respond to the virus by mounting an excessive T cell response and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It may be that PLP is able to contribute to dampening the cytokine storm and inflammation suffered by some COVID-19 patients.

1.6. Vitamin B9 (folic acid, folate)

Folate is an essential vitamin for DNA and protein synthesis and in the adaptive immune response. Furin is an enzyme associated with bacterial and viral infections and is a promising target for treatment of infections. Recently, it was noted that folic acid was able to inhibit furin, preventing binding by the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, preventing cell entry and virus turnover. Therefore it was suggested that folic acid could be beneficial for the management of COVID-19-associated respiratory disease in the early stages [25]. A recent preprint report that folic acid and its derivatives tetrahydrofolic acid and 5-methyl tetrahydrofolic acid have strong and stable binding affinities against the SARS-CoV-2, through structure-based molecular docking. Therefore, folic acid may be used as a therapeutic approach for the management of COVID-19 [26].

1.7. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin)

Vitamin B12 is essential for red blood cell synthesis, nervous system health, myelin synthesis, cellular growth and the rapid synthesis of DNA. The active forms of vitamin B12 are hydroxo-, adenosyl- and methyl-cobalamin. Vitamin B12 acts as a modulator of gut microbiota and low levels of B12 elevate methylmalonic acid and homocysteine, resulting in increased inflammation, reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress [15]. Hyperhomocysteinemia causes endothelial dysfunction, activation of platelet and coagulation cascades, megaloblastic anemia, disruption of myelin sheath integrity and decreased immune responses [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. However, SARS-CoV-2 could interfere with vitamin B12 metabolism, thus impairing intestinal microbial proliferation. Given that, it is plausible that symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency are close to COVID-19 infection such as elevated oxidative stress and lactate dehydrogenase, hyperhomocysteinemia, coagulation cascade activation, vasoconstriction and renal and pulmonary vasculopathy [28,31]. In addition, B12 deficiency can result in disorders of the respiratory, gastrointestinal and central nervous systems [30]. Surprisingly, a recent study showed that methylcobalamin supplements have the potential to reduce COVID-19-related organ damage and symptoms [32]. A clinical study conducted in Singapore showed that COVID-19 patients who were given vitamin B12 supplements (500 μg), vitamin D (1000 IU) and magnesium had reduced COVID-19 symptom severity and supplements significantly reduced the need for oxygen and intensive care support [33].

2. What is the outcome?

Vitamin B not only helps to build and maintain a healthy immune system but it could potentially prevent or reduce COVID-19 symptoms or treat SARS-CoV-2 infection. Poor nutritional status predisposes people to infections more easily; therefore, a balanced diet is necessary for immuno-competence. There is a need for safe and cost-effective adjunct or therapeutic approaches, to suppress aberrant immune activation, which can lead to a cytokine storm, and to act as anti-thrombotic agents. Adequate vitamin intake is necessary for proper body function and strengthening of the immune system. In particular, vitamin B modulates immune response by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammation, reducing breathing difficulty and gastrointestinal problems, preventing hypercoagulability, potentially improving outcomes and reducing the length of stay in the hospital for COVID-19 patients.

Contributors

Hira Shakoor contributed to the writing and revision of this editorial.

Jack Feehan contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Kathleen Mikkelsen contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Ayesha S Al Dhaheri contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Habiba I Ali contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Carine Platat contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Leila Cheikh Ismail contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Lily Stojanovska contributed to the revision of this editorial.

Vasso Apostolopoulos conceptualized the editorial and contributed to the writing, revision and approval of the final version of this editorial.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this editorial.

Provenance and peer review

This article was commissioned and was not externally peer reviewed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

VA would like to thank the Immunology and Translational Research Group and the Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University for their support. KM was supported by the Victoria University postgraduate scholarship and the Vice Chancellors top up scholarship. JF was supported by the University of Melbourne Postgraduate Scholarship. VA would like to thank the Thelma and Paul Constantinou Foundation, and The Pappas Family, whose generous philanthropic support made possible the preparation of this paper. HS, AD, HA, CP LS would like to acknowledge the Department of Food, Nutrition and Health, United Arab Emirates University, and LI would like to acknowledge the Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Department, University of Sharjah for their ongoing support.

References

- 1.Zu Z.Y., Jiang M.D., Xu P.P., Chen W., Ni Q.Q., Lu G.M., Zhang L.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a perspective from China. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang C., Wu Z., Li J.-W., Zhao H., Wang G.-Q. The cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of severe COVID-19 and interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce the mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zumla A., Hui D.S., Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. The Lancet. 2015;386(9997):995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shakoor H., Feehan J., Al Dhaheri S.A., Ali I.H., Platat C., Ismail C.L., Apostolopoulos V., Stojanovska L. Immune boosting role of vitamins D, C, E, zinc, selenium and omega-3 fatty acids: could they help against COVID-19? Maturitas. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikkelsen K., Apostolopoulos V. Vitamin B.1, B2, B3, B5, and B6 and the immune system. Nutr. Immunity. 2019:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michele C.A., Angel B., Valeria L., Teresa M., Giuseppe C., Giovanni M., Ernestina P., Mario B. Vitamin supplements in the era of SARS-Cov2 pandemic. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2020;11(2):007–019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L., Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdemir Z.O., Senturk M., Ekinci D. Inhibition of mammalian carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II and VI with thiamine and thiamine-like molecules. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013;28(2):316–319. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2011.637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragan I., Hartson L., Pidcoke H., Bowen R., Goodrich R. Pathogen reduction of SARS-CoV-2 virus in plasma and whole blood using riboflavin and UV light. Plos One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keil S.D., Ragan I., Yonemura S., Hartson L., Dart N.K., Bowen R. Inactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in plasma and platelet products using a riboflavin and ultraviolet light‐based photochemical treatment. Vox Sang. 2020 doi: 10.1111/vox.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boergeling Y., Ludwig S. Targeting a metabolic pathway to fight the flu - boergeling - 2017. FEBS J. - Wiley Online Library. 2020 doi: 10.1111/febs.13997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikkelsen K., Apostolopoulos V. B vitamins and ageing, biochemistry and cell biology of ageing: part I biomedical science. Springer. 2018:451–470. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-2835-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikkelsen K., Stojanovska L., Apostolopoulos V. The effects of vitamin B in depression. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016;23(38):4317–4337. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160920110810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikkelsen K., Stojanovska L., Prakash M., Apostolopoulos V. The effects of vitamin B on the immune/cytokine network and their involvement in depression. Maturitas. 2017;96:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu B., Li M., Zhou Z., Guan X., Xiang Y. Can we use interleukin-6 (IL-6) blockade for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-induced cytokine release syndrome (CRS)? J. Autoimmun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai A., Matsumiya H., Hayashi M., Yasui S., Okamoto H., Konno K. Effects of nicotinamide and niacin on bleomycin-induced acute injury and subsequent fibrosis in hamster lungs. Exp. Lung Res. 1994;20(4):263–281. doi: 10.3109/01902149409064387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mario M., Nina J., Urs S. Nicotinamide riboside—the current State of research and therapeutic uses. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1616. doi: 10.3390/nu12061616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merigliano C., Mascolo E., Burla R., Saggio I., Vernì F. The relationship between vitamin B6, diabetes and cancer. Front. Genet. 2018;9:388. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lengyel C.O., Whiting S.J., Zello G.A. Nutrient inadequacies among elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2008;69(2):82–88. doi: 10.3148/69.2.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nix W.A., Zirwes R., Bangert V., Kaiser R.P., Schilling M., Hostalek U., Obeid R. Vitamin B status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without incipient nephropathy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015;107(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desbarats J. 2020. Pyridoxal 5’-Phosphate to Mitigate Immune Dysregulation and Coagulopathy in COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Wyk V., Luus H.G., Heyns Ad.P. The in vivo effect in humans of pyridoxal-5′-phosphate on platelet function and blood coagulation. Thrombosis Res. 1992;66(6):657–668. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikkelsen K., Prakash M.D., Kuol N., Nurgali K., Stojanovska L., Apostolopoulos V. Anti-tumor effects of vitamin B2, B6 and B9 in promonocytic lymphoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(15) doi: 10.3390/ijms20153763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheybani Z., Dokoohaki M.H., Negahdaripour M., Dehdashti M., Zolghadr H., Moghadami M., Masoompour S.M., Zolghadr A.R. 2020. The Role of Folic Acid in the Management of Respiratory Disease Caused by COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar V., Jena M. 2020. In Silico Virtual Screening-Based Study of Nutraceuticals Predicts the Therapeutic Potentials of Folic Acid and Its Derivatives Against COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemazannikova N., Mikkelsen K., Stojanovska L., Blatch G.L., Apostolopoulos V. Is there a link between vitamin B and multiple sclerosis? Med. Chem. 2018;14(2):170–180. doi: 10.2174/1573406413666170906123857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabry W., Elemary M., Burnouf T., Seghatchian J., Goubran H. Vitamin B12 deficiency and metabolism-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (MM-TMA) Transfusion Apheresis Sci. 2020;59(1) doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2019.102717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stipp M.M. SARS-CoV-2: micronutrient optimization in supporting host immunocompetence. Int. J. Clin.Case Rep. Rev. 2020;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolffenbuttel B.H.R., Wouters H.J.C.M., Heiner-Fokkema M.R., Van der klauw M.M. The many faces of cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency. Mayo Clin. Proc.: Innov. Quality Outcomes. 2019;3(2):200–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grangé S., Bekri S., Artaud-Macari E., Francois A., Girault C., Poitou A.-L., Benhamou Y., Vianey-Saban C., Benoist J.-F., Châtelet V. Adult-onset renal thrombotic microangiopathy and pulmonary arterial hypertension in cobalamin C deficiency. Lancet (London, England) 2015;386(9997):1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos L.M.J. Can vitamin B12 be an adjuvant to COVID-19 treatment? GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2020;11(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan C.W., Ho L.P., Kalimuddin S., Cherng B.P.Z., Teh Y.E., Thien S.Y., Wong H.M., Tern P.J.W., Chay J.W.M., Nagarajan C. A cohort study to evaluate the effect of combination vitamin D, magnesium and vitamin B12 (DMB) on progression to severe outcome in older COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.111017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]