Abstract

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common reproductive/metabolic condition associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D) and depression in adult women. Depression in adults is related to PCOS dermatologic manifestations. Adolescents with obesity +/− T2D have elevated depression symptoms, but data from youth with PCOS and obesity +/− T2D are limited.

Methods

Girls ages 11–17 years with obesity and PCOS, PCOS+T2D or T2D, newly seen in a obesity complications clinic after 3/2016 with Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (20-item; CES-D) scores within 6 months of PCOS or T2D diagnosis were included. Data on history of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, metabolic syndrome and severity of acne and hirsutism were collected via chart review.

Results

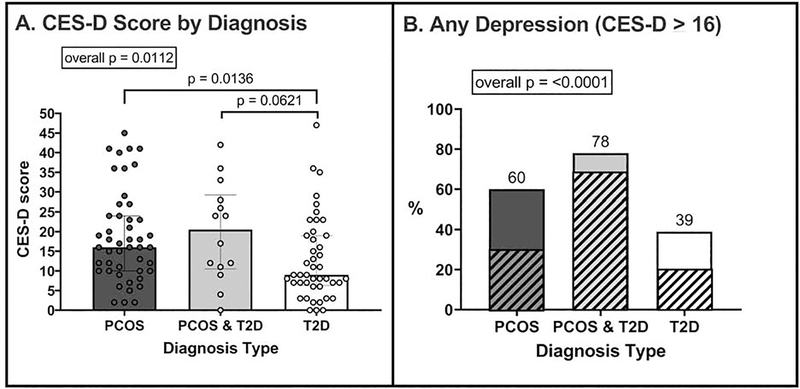

105 girls (n=47 PCOS, n=14 PCOS+T2D, n=44 T2D) had similar age (15y±1.8 years) and BMI-z scores (2.2±0.4). A CES-D score ≥16, indicating elevated depression symptoms, and a CES-D score ≥24, indicating severe depression symptoms, were observed in 60% and 30% with PCOS, respectively, 78% and 71% with PCOS+T2D, compared to 39% and 21% with T2D (p<0.0001 for both cut-points). A higher CES-D was not associated with severity of hirsutism or acne (p>0.05 for both).

Conclusions

Adolescents with PCOS and obesity have higher rates of elevated depression symptoms compared to girls with T2D, which is not related to worse dermatologic symptoms. Since depression may impact both PCOS and T2D management and adherence to therapy, greater efforts should be made to screen for and address mental health in adolescents with PCOS and obesity, especially if T2D is present.

Keywords: Depression, adolescents, type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder that affects 6–10% of women.1 Among adolescents with obesity, the prevalence of PCOS is even higher, ranging from 18–27%.2 PCOS commonly includes clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism, including oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, and acne. Adult women and adolescents with PCOS also have an increased risk for developing comorbidities including type 2 diabetes (T2D), infertility, obesity, cardiovascular disease, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and other metabolic disorders.3

Recent work indicates that adult women with PCOS have a higher risk for psychological difficulties, particularly internalizing symptoms. In a meta-analysis of 18 studies across the world, adult women with PCOS had a three-fold increase in prevalence of depression and five-fold increase for anxiety compared to women without PCOS.4 One longitudinal study that followed 83 adult women with PCOS over 25 years reported that depression symptom scores, assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale, were consistently higher than women without PCOS at each assessment point. Women with PCOS were 2 times more likely to have positive depression screens compared to women without PCOS.5 Reasons for increased rates of depression symptoms in women with PCOS are unclear, but are thought to relate to severity of cosmetic symptoms, metabolic disease, and/or infertility.4 It is also possible that the converse is true, i.e. that depression symptoms may play a role, through stress-related behavioral and physiological mechanisms, in the pathophysiology of PCOS.6 Although prevalence of depression has been studied in women with PCOS, the extent of depression in youth with PCOS has not been characterized and related factors are unknown.

The prevalence of depression in adolescents overall is 11%, with girls having a two- to three-fold increased risk for major depressive disorder compared to males.7 Rates of depression diagnosis in girls with obesity and/or metabolic disease vary from 12–21%.8,9 The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study showed that adolescents with obesity and T2D had greater depression symptoms per CES-D than adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D), with a greater proportion of T2D adolescents with scores ≥16, the cutoff for significant depressive symptoms, necessitating further evaluation for depression.10 Similarly, in the TODAY study, which included 704 youth with T2D between the ages of 10–17 years with BMI≥85th percentile, 17% of girls had clinically elevated depressive symptoms.11 These increased rates of depression in adolescents with obesity and T2D, coupled with the increased risk of depression in adults with PCOS, indicates that adolescents with PCOS and obesity may be at risk, but these rates are as yet undefined. We hypothesized that the girls with PCOS would have similar rates of depressive symptoms to girls with T2D. Thus, the aims of our study were to characterize and compare depression symptoms in adolescent patients with obesity presenting with PCOS and/or T2D and to evaluate the relationship of patient demographic, medical and laboratory characteristics to depressive symptoms.

Methods

Data Collection

This manual retrospective chart review examined electronic medical records of patients from a clinic for youth with medical complications of obesity at Children’s Hospital Colorado, a large tertiary referral center with a catchment area including 7 states. This research was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. The initial medical record search included the following parameters: 1) age 11–17 years, 2) female, 3) at least one clinic visit after the CES-D was introduced to systematically screen for depression in all patients (March 2016 to June 2019) 4) ICD9/10 codes for “obesity” i.e. BMI ≥95th percentile for age/sex or “overweight” i.e. 85–94 percentile for age/sex 5) visit location=“Lifestyle Medicine Clinic” and 6) ICD9/10 codes “polycystic ovaries” and “irregular menses” or “type 2 diabetes”. These charts (N=201), were then evaluated to ensure that a diagnosis of PCOS was verified per Endocrine Society guidelines (oligomenorrhea > 2 years post menarche and clinical/biochemical hyperandrogenisism, with no other cause of oligomenorrhea or elevated androgens noted) and/or American Diabetes Association criteria for T2D diagnosis (2 measures of a combination of the following: HbAlc >6.5%, fasting blood sugar > 7 mmol/L or random blood glucose > 11.1 mmol/L and negative antibodies for type 1 diabetes).12,13 Patients who did not have a CES-D collected within 6 months of PCOS or T2D diagnosis were also excluded. This occurred when the diagnosis was made well before the referral to the Lifestyle Medicine Clinic, a patient or family refused to fill out the survey, or the patient had an intellectual disability such that the psychologist in clinic was concerned that the data were invalid. Surveys were only included when the patient was within 6 months of diagnosis, to avoid the possibility that the treatment for T2D or PCOS would affect the scores. The final cohort included 105 girls with overweight/obesity and either PCOS (N=47), PCOS+T2D (N=14) or T2D only (N=44) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| PCOS (n=47) | PCOS+T2D (n=14) | T2D (n=44) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.6 (14.6, 16.8) | 14.5 (13.9, 16.3) | 14.51 (12.5, 16.5)*a |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 34.9 (30.9, 41.8) | 34.74 (31.4, 39.7) | 34.8 (29.6, 42.6) |

| BMI z score | 2.2 (1.8, 2.5) | 2.5 (1.9, 2.7) | 2.4 (2.1, 2.6) |

| BMI percentile | 98.7 (96.9, 99.3) | 98.1 (96.8, 99.5) | 98.97 (97.6, 99.5) |

| Race | |||

| White | 33 (70.2%) | 7 (50.0%) | 31 (70.5%)* |

| African American | 5 (10.6%) | 1 (7.1%) | 6 (13.6%) |

| Asian | 3 (6.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| More than 1 race | 1 (2.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (10.6%) | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (11.4%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 17 (36.2%) | 8 (57.1%) | 24 (54.5%)* |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 17 (36.2%) | 1 (7.1%) | 16 (36.4%) |

| Not reported | 13 (27.7%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (9.1%) |

| Insurance | |||

| Public | 23 (48.9%) | 10 (71.4%) | 34 (77.3%) |

| Private | 21 (44.7%) | 3 (21.4%) | 9 (20.5%) |

| None | 3 (6.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Living situation | |||

| Living 2 parents | 33 (70.2%) | 7 (50%) | 25 (56.8%) |

| Single parents | 13 (27.7%) | 7 (50%) | 10 (22.7%) |

| Biological non-parent | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (15.9%) |

| Foster | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Food insecurity | 7 (28.0%) | 8 (61.5%) | 14 (35.0%) |

| Home school | 7 (15.2%) | 4 (50.0%) | 2 (4.7%)* |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5 (5.3, 5.6) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.1) | 7.4 (6.6, 9.97)*a |

| SBP (mm/Hg) | 120 (116, 125) | 113 (110, 120) | 116 (112,120)*a |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 144 (100, 216) | 126 (90, 205) | 186 (134, 245) |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 41 ± 7.5 | 39 ± 7.1 | 35 ± 6.7*a |

| ALT (IU/L) | 32 (29, 47) | 36 (24, 70) | 37 (24, 69) |

| AST (IU/L) | 33 (21, 51) | 38 (31, 50) | 35 (23, 66) |

| Free Testosterone (ng/uL) | 8.7 (6.8, 12.0) | 8.2 (6.9, 15.5) | 2.4+ (1.8, 2.9)*a, b |

significant overall p-value

significant between PCOS and T2D

Significant between PCOS+T2D and T2D

n=3

From the final cohort, key sociodemographic and diagnostic information were collected from time of PCOS or T2D diagnosis. Demographic information included age at PCOS or T2D diagnosis, self-reported race and ethnicity, insurance type (public, private, none), living situation (2 parent, single parent, biological non-parent, foster home), food insecurity as assessed by a trained dietician, and home schooling. Diagnostic information included BMI, BMI percentile, BMI z-value, blood pressure, history of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), depression, or anxiety, and a family history of a first-degree relative with PCOS, T2D, obesity, anxiety, depression, OSA or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). The following lab measurements were recorded from within 6 months of PCOS or T2D diagnosis: HbAlc, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein (HDL), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and free testosterone. Data on current use of prescription of metformin, estrogen containing therapies, progesterone, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or blood pressure medications was collected from the same visit that the CES-D score was obtained. Mental health history, both self-reported and extracted from events within the electronic medical record, included past history of bullying, documented suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, self-harm, drug or alcohol abuse, mental health admission or emergency room visit. The prescription of anti-psychotics, anxiety or depression medications, and individual counseling was recorded only if within 1 year of CES-D survey. Severity of cosmetic characteristics including acanthosis, hirsutism via the Ferriman-Gallwey Score (FGS), and acne from time of diagnosis were also recorded.

Depression symptoms were measured with the 20-item CES-D total score, a validated tool for assessing depression symptoms in both adults and adolescents.14,15 The questionnaire is given to the patient when they are placed in a clinic room, and completed by the patient without staff assistance. All answers are then uploaded into a custom-built flowsheet in the electronic medical record for calculation of the total score. All items are rated on a scale from 0 to 3, and scores are summed to obtain a total score, which for the purposes of the current study was examined continuously and categorized into 3 standardly reported severity groups: none (0–15), mild (16–23), and severe depression symptoms (24–60) (Figure 1).16,17 These cut points and desscriptions are equivalent to those used in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study.18 Girls with scores ≤ 24, but who were prescribed anti-psychotic, depression, or anxiety medications within 1 year of their CES-D measure were classified in the severe category, as American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines indicate that medication should only be prescribed to adolescents in cases of moderate or severe depression.19

Figure 1: CES-D scores and percentage of scores in depressive range.

A. CES-D scores for each patient are shown per category. The scores were different across the groups, and also between groups. B. The overall percentage of scores ≥ 16 is shown with the percentage noted above the bar. The shaded area represents the percentage of scores which were ≥ 24. For PCOS, 30% are mild and 30% severe, for PCOS +T2D, 7 % are mild and 71% severe and for T2D, 18% are mild and 21% severe.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were classified into groups based on diagnosis: PCOS, PCOS+T2D, or T2D. Descriptive statistics reported include mean ± standard deviation and median (25th%, 75th%) for continuous normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively, while categorical variables were reported as count (percentage). To compare continuous variables between the groups, an ordinary one-way ANOVA for normally distributed data or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normal data distributions were used. All categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests. Further analysis used Dunnett’s or Dunn’s multiple comparison tests to assess differences in the PCOS and PCOS+T2D groups compared to the T2D group. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression was conducted based on CES-D score and severity to identify potential predictors of depression symptoms. Simple linear/logistic regression as well as step-wise selected linear/logistic regression based on AIC (Akaike Information Criteria) were then conducted on measures of depression symptoms with the significant associations identified by LASSO, along with number of cosmetic symptoms. A significant p-value was defined as p<0.05 for all analyses. Analyses were conducted using Prism 8.1 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and R 3.5 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographic, anthropomorphic, social history and metablic data at the time of CES-D are shown in Table 1. Of note, the average age and BMI-Z at diagnosis were similar across all conditions (Table 1). As expected, HbA1c was higher in both groups with T2D and free testosterone was higher both groups with PCOS. However, since free testosterone level is not a standard measure for T2D visits, it was only recorded for 3 out of 44 girls with T2D. Whereas HDL was lowest in the T2D only group,systolic blood pressure was highest in the PCOS only group.Rates of diagnosed OSA were different between the groups, and higher in PCOS+T2D (overall p=0.043; PCOS vs T2D pairwise p=0.741; PCOS vs PCOS+T2D pairwise p=0.106; PCOS+T2D vs T2D pairwise p= 0.030). A family history of T2D was more common in both groups with T2D and Rates of reported maternal GDM were different between the groups (overall p<0.001; PCOS vs T2D pairwise p<0.001; PCOS vs PCOS+T2D pairwise p=0.223; PCOS+T2D vs T2D pairwise p= 0.106).

The prevalence of any elevated depression symptoms (CES-D≥16) in girls with PCOS alone was 60% (Figure 1B). Whereas girls in the T2D alone group had a median CES-D score in the “none” range (9.0 [6.3, 19.0]), girls with PCOS alone (16.0 [10.0, 24.0]) and PCOS+T2D (20.5 [10.5, 29.3]) have, on average, depression symptom scores in the mild range (Figure 1A). Girls with PCOS+T2D had the highest rate of “severe” depression scores at 71%, followed by girls with PCOS (30%), then T2D (21%) (striped bars in Figure 1B). The proportion of individuals with any depressive symptoms was significantly different between the groups (p<0.0001), as were the proportions of mild and severe depressive symptoms scores. LASSO and linear regression showed that a diagnosis of PCOS was associated with a 6.8-point higher CES-D score (p=0.001). The degree of obesity did not relate to the CES-D score.

Mental health history for the three groups is shown in table 2. Some of the patients in this cohort were already receiving some form of care for depression, and among the entire cohort, with 34% receiving counseling, 16% prescribed antidepressants and an additional 10% seeing a psychiatrist, Table 2. Of the mental health characteristics, only history of taking antidepressants was significantly different between groups (p = 0.024). A past medical history of depression and a family history of anxiety were both independently associated with 6.3 point (p=0.03) and 16.2 point (p=0.01) greater CES-D score, respectively. Patients that were prescribed anti-psychotic medication had a CES-D score 12.7 points lower on average than patients who were not prescribed anti-psychotics (p=0.028).

Table 2:

Clinical characteristics of the population

| PCOS (n=47) | PCOS+T2D (n=14) | T2D (n=44) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal History | |||

| Sleep apnea | 6 (12.8%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (9.1%)* |

| Anxiety | 7 (14.9%) | 3 (21.4%) | 8 (18.2%) |

| Depression | 10 (21.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 12 (27.3%) |

| Family History | |||

| PCOS | 7 (14.9%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.1%) |

| T2D | 7 (14.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | 21 (47.7%)* |

| Obesity | 10 (21.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 14 (31.8%) |

| Anxiety | 2 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Depression | 6 (12.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Mental Health History | |||

| Bullying | 10 (33%) | 1 (9%) | 12 (39%) |

| Antipsychotics | 1 (2%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (5%) |

| Antidepressants | 6 (13%) | 6 (43%) | 5 (11%)* |

| Counseling | 16 (34%) | 7 (50%) | 13 (30%) |

| Psychiatrist | 5 (11%) | 2 (14%) | 4 (9%) |

| Documented suicidal ideation | 7 (14.8%) | 5 (35.7%) | 10 (22.7%) |

| Suicide attempt | 3 (6.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Self-harm | 7 (14.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Mental health admission | 4 (8.5%) | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (6.8%) |

| Mental health ED visit | 4 (8.5%) | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (6.8%) |

significant overall p-value

When the 3 groups in the cohort were combined and recategorized by depression status, compared to girls with no depression symptoms, girls with any depression symptoms were more likely to be homeschooled (4% versus 20%, p = 0.018), although reported rates of bullying (18% versus 25%, p = 0.483) and food insecurity (24% versus 30%, p = 0.521) were similar between groups, and common within this cohort. Girls with depression were more likely to be multi-racial (overall p=0.016; pairwise multi vs black p=0.042; pairwise multi vs Hispanic p=0.002; pairwise multi vs non-Hispanic white p=0.012).

The severity of cosmetic symptoms is shown in Table 3. Acanthosis scores were similar in the 3 groups (p = 0.20). However, hirsutism and acne were significantly different across groups (p<0.001 for both). Severity of hirsutism was divided into 4 categories based on FGS: none (0–5), mild (6–11), moderate (12–16), severe (≥ 17). In the T2D group, 2% of the population had hirsutism, while 42% of the PCOS+T2D and 37% of the PCOS population had mild to severe hirsutism. Acne had the lowest prevalence in the T2D group with 47% of the population having mild or moderate acne, while the majority of the PCOS+T2D (69%) and PCOS (52%) groups had mild acne. However, there were no significant associations between CES-D score and acanthosis, FGS or acne.

Table 3:

Cosmetic characteristics of the population

| PCOS | PCOS & T2D | T2D | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthosis | 0.1988 | |||

| 0 | 7 (15%) | 2 (14%) | 2 (5%) | |

| 1 | 11 (24%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (7%) | |

| 2 | 10 (22%) | 3 (21%) | 9 (21%) | |

| 3 | 8 (17%) | 3 (21%) | 13 (30%) | |

| 4 | 10 (22%) | 5 (36%) | 16 (37%) | |

| Hirsutism | 0.0016 | |||

| None | 28 (62%) | 8 (57%) | 42 (98%) | |

| Mild | 10 (22%) | 3 (21%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Moderate | 5 (11%) | 3 (21%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Severe | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Acne | 0.0004 | |||

| None | 6 (14%) | 2 (15%) | 23 (53%) | |

| Mild | 23 (52%) | 9 (69%) | 18 (42%) | |

| Moderate | 13 (30%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Severe | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

Discussion

Our study reported that among treatment-seeking adolescent girls with obesity, rates of elevated depression symptoms are highest in girls who present with combined PCOS+T2D, followed by PCOS alone, then T2D alone. Our findings of increased rate of depression symptoms in adolescent girls with PCOS compared to girls without PCOS are similar to findings in adult women with PCOS, in which the median prevalence of depression was 37%, compared to 14.2% in adult women without PCOS.4 Rate of severe depression symptoms, defined as a CES-D≥24 or anti-depressant medication prescription, in our T2D group was 21%, slightly higher than a previously published rate of baseline elevated depression symptoms (16.8%) in girls with T2D in the TODAY study, a large multicenter treatment trial of T2D in youth. The differences in rates could be attributed to the different race distributions in the 2 studies as there are associations with increased depressive symptoms and difference race and ethnicities in teens. Despite these findings of increased rates of depression symptoms, the majority of adolescents across all diagnosis groups with elevated depression symptoms (CES-D≥16), were not receiving any sort of menal health treatment.. Only 49% were receiving any sort of mental health treatment, with 20% of adolescents on anti-depressants and 43% receiving counseling. Given that so many adolescents with PCOS, PCOS+T2D, and T2D have elevated depressive symptom scores, yet more than half were not receiving care, our findings highlight the necessity of screening and referring adolescents to mental health treatment.

Obesity itself has been related to high depression symptom scores in both adolescents and adults. A meta-analysis found a significant association between obesity and depression (p = 0.005), and increased severity of depression in adolescents with obesity compared to those who were not-obese.20 Additionally, symptoms of severe depression were more prevalent in females than males. Adolescents with obesity were shown to have a 1.5-fold increased risk of developing major depressive disorder between the ages of 14–20 compared to adolescents without obesity, and obesity during adolescence was predictive of later depression in females.8 Obesity is a common comorbidity associated with PCOS; among adult women with PCOS, those with elevated depression symptoms had higher BMIs. However, after matching PCOS and no PCOS controls on BMI, increased prevalence of depression symptoms remained, suggesting that the increase in depression in PCOS is independent of BMI. This could explain why the degree of obesity within our cohort did not relate to severity of depression in any of our subcategories or the group as a whole. This may also be due to a limited range of BMI, and perhaps if we had been able to survey girls with PCOS without obesity we would have seen a relationship between depression and obesity. Depression may also be predictive of later obesity or T2D onset, as recent work has shown depression predicts worsening insulin resistance.

In adult women with PCOS, depressive or anxiety symptoms were positively associated with more severe hirsutism (higher FGS).4 However, in adolescent girls with PCOS, we did not see this association between severity of cosmetic symptoms and depression.21 It may be that a more generalized assessment of satisfaction with appearance is needed for this cohort. A recent study in youth with T2D found that higher depressive symptoms were associated with a lower self-rated global health score, and this has previously also been demonstrated with adults with T2D.22,23 It may be that dermatologic symptoms are only part of scope of problems that girls with PCOS face, and thus alone are not sensitive enough of a measure, as obese adolescents with PCOS can also have menstrual irregularities, concerns about metabolic health, fertility and multiple other issues. The many types of symptoms associated with PCOS which can affect adolescents self-preceptions of health could perhaps explain the higher rates of depressive symptoms and future work should include a global health survey to test this hypothesis.

Our study has several limitations. Since this was a retrospective chart review, data collection was dependent on physicians drawing the relevant lab variables at visits. As a result, several patients had outdated labs (not within 6 months of diagnosis) or missing lab variables, and these values were excluded from analysis. It is also possible that cases that met criteria for inclusion were missed. In addition, although the CES-D scale has been implemented in our Lifestyle Medicine Clinic since 3/2016, many participants were excluded from the study due to a missing CES-D score. Reasons for missing CES-D scores include patient/parental refusal to complete the CES-D questionnaire, patient visit cut short, failure of provider to distribute CES-D, or the patient not able to complete the survey due to an intellectual disability. The CES-D was also not available in Spanish, which potentially limited participation or did not accurately assess girls who were primarily Spanish speaking. Additionally, given that Lifestyle Medicine clinic is a referral center, our patients may not be representative a typical PCOS population, as they have been identified by their primary provider as needing multidisciplinary care. Finally, as a referral clinic for metabolic complication of obesity, we do not have data from our site in girls with obesity, but not PCOS or T2D. Finally, we elected to only use CES-D scores within 6 months of PCOS diagnosis, to avoid any possible effects of PCOS treatment on the scores, but this may reflect a higher stress time for patients, as they are coping with a new diagnosis.

There are also several strengths in our study. Our sample size was relatively large with similar age and BMI across all 3 groups. Furthermore, all PCOS and T2D diagnoses were confirmed by a pediatric endocrinologist in accordance with the latest Endocrine Society and ADA guidelines.

Conclusions

Adolescent girls with PCOS and obesity seen in a multi-disciplinary obesity clinic experience elevated symptoms of depression compared to girls with T2D and obesity, and those with T2D,PCOS and obesity have the highest rates of depressive symptoms. Future studies should include girls with PCOS across a range of BMI values to further examine the relationship between obesity and depression in girls with PCOS. Additionally, routine depression screenings should be implemented at all PCOS visits, especially when PCOS and T2D are present. The finding of elevated depression symptom scores, along with the potential effect of depression on PCOS and T2D management and adherence to therapy recommendations, emphasizes an urgent need to identify and address mental health concerns to better provide clinical care for adolescents with PCOS, T2D and obesity.

Key Messages.

Depression is common in women with PCOS and obesity but less studied in teens. In obese youth, 60% of PCOS, 78% of PCOS + T2D and 39% of T2D had depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Dr. Cree-Green is supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K23DK107871 and Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Abbreviations

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- IR

insulin resistance

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- PYs

person years

- ADA

American Diabetes Association

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- EMR

electronic medical record

- BMI

body mass index

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- GDM

gestational diabetes mellitus

Footnotes

Author Disclosures: The authors have no direct conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-¬analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ybarra M, Franco RR, Cominato L, Sampaio RB, Sucena da Rocha SM, Damiani D. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome among Obese Adolescents. Gynecological endocrinology : the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology. 2018;34(1):45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsikouras P, Spyros L, Manav B, et al. Features of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in adolescence. Journal of medicine and life. 2015;8(3):291–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, Dokras A. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(5):1075–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwood EA, Yaffe K, Wellons MF, Cedars MI, Huddleston HG. Depression Over the Lifespan in a Population-Based Cohort of Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Longitudinal Analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2019;104(7):2809–2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooney LG, Dokras A. Depression and Anxiety in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Etiology and Treatment. Current psychiatry reports. 2017;19(11):83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He JP, Burstein M, Merikangas KR. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):37–44 e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG, Legrand L. Obesity and depression in adolescence and beyond: reciprocal risks. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(7):906–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson AD, Solorzano CM, McCartney CR. Childhood obesity and its impact on the development of adolescent PCOS. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2014;32(3):202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood KK, Beavers DP, Yi-Frazier J, et al. Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2014;55(4):498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson BJ, Edelstein S, Abramson NW, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in adolescents with type 2 diabetes: baseline data from the TODAY study. Diabetes care. 2011;34(10):2205–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(12):4565–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes A 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S13–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale:A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips GA, Shadish WR, Murray DM, Kubik M, Lytle LA, Birnbaum AS. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale With a Young Adolescent Population: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2006;41(2):147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon JR, Huh J, Song J, et al. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is an adequate screening instrument for depression and anxiety disorder in adults with congential heart disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nip ASY, Reboussin BA, Dabelea D, et al. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth and Young Adults With Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Insulin Therapy: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes care. 2019;42(5):859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Laraque D, Stein REK, Glad-Pc Steering G. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and Ongoing Management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quek YH, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):742–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins CS, Kimble LP, Hodges HF, Koci AF, Mills BB. A mixed-methods study of coping and depression in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2019;31(3):189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong JJ, Addala A, Abujaradeh H, et al. Depression in context: Important considerations for youth with type 1 vs type 2 diabetes. Pediatric diabetes. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehme S, Geiser C, Renneberg B. Functional and self-rated health mediate the association between physical indicators of diabetes and depressive symptoms. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]