Abstract

Background

VEGF‐D (vascular endothelial growth factor D) and VEGF‐C are secreted glycoproteins that can induce lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis. They exhibit structural homology but have differential receptor binding and regulatory mechanisms. We recently demonstrated that the serum VEGF‐C level is inversely and independently associated with all‐cause mortality in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease. We investigated whether VEGF‐D had distinct relationships with mortality and cardiovascular events in those patients.

Methods and Results

We performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 2418 patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease undergoing elective coronary angiography. The serum level of VEGF‐D was measured. The primary outcome was all‐cause death. The secondary outcomes were cardiovascular death and major adverse cardiovascular events defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. During the 3‐year follow‐up, 254 patients died from any cause, 88 died from cardiovascular disease, and 165 developed major adverse cardiovascular events. After adjustment for possible clinical confounders, cardiovascular biomarkers (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide, cardiac troponin‐I, and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein), and VEGF‐C, the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death and cardiovascular death but not with major adverse cardiovascular events.. Moreover, the addition of VEGF‐D, either alone or in combination with VEGF‐C, to the model with possible clinical confounders and cardiovascular biomarkers significantly improved the prediction of all‐cause death but not that of cardiovascular death or major adverse cardiovascular events. Consistent results were observed within patients over 75 years old.

Conclusions

In patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease undergoing elective coronary angiography, an elevated VEGF‐D value seems to independently predict all‐cause mortality.

Keywords: all‐cause death, biomarker, cardiovascular events, coronary artery disease, prospective cohort study

Subject Categories: Biomarkers, Clinical Studies, Coronary Artery Disease, Mortality/Survival, Growth Factors/Cytokines

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the first, dedicated and large‐scale prospective cohort study to demonstrate that the VEGF‐D (vascular endothelial growth factor D) level is significantly associated with all‐cause mortality among patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease, in sharp contrast to the fact that the VEGF‐C level is inversely associated with all‐cause mortality in those patients.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

An elevated VEGF‐D level in sera from arterial catheter sheath at the beginning of elective coronary angiography independently predicts all‐cause mortality in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease beyond the potential clinical confounders, NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide), cTnI (contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin‐I), hs‐CRP (high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein), and VEGF‐C (vascular endothelial growth factor C).

Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms that regulate circulating VEGF‐D and VEGF‐C levels, and their effect on cardiovascular system.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms.

ANOX Development of Novel Biomarkers Related to Angiogenesis or Oxidative Stress to Predict Cardiovascular Events

BMI body mass index

CAD coronary artery disease

CKD chronic kidney disease

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

cTnI contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin‐I

CV coefficients of variation

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

EXCEED‐J Establishment of the Method to Extract a High Risk Population Employing Novel Biomarkers to Predict Cardiovascular Events in Japan

HR hazard ratio

hs‐CRP high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein

IDI integrated discrimination improvement

LAM lymphangioleiomyomatosis

MACE major adverse cardiovascular events

mTOR mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin

NHO National Hospital Organization

NRI net reclassification improvement

NT‐proBNP N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide

PlGF placental growth factor

PREHOSP‐CHF Development of Novel Biomarkers to Predict Rehospitalization in Chronic Heart Failure

TSC tuberous sclerosis complex

VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

VEGFR VEGF receptor

Introduction

The VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) family and their endothelial tyrosine kinase receptors are central regulators of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis.1 The VEGF family consists of five members in mammals: VEGF (or VEGF‐A), PIGF (placental growth factor), VEGF‐B, VEGF‐C, and VEGF‐D. Among them, VEGF‐C and VEGF‐D are secreted glycoproteins that exhibit structural homology, and both of them can promote lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis by binding to their specific receptors, VEGF receptor (VEGFR)‐2 and VEGFR‐3.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 However, VEGF‐C and VEGF‐D have differential receptor binding, regulatory mechanisms,7 and expression patterns during development and in adult tissues in mice8, 9 as well as in human tumors.10, 11 During embryonic development, VEGF‐D appears to play a subtler role in regulating lymphatic vascular development than VEGF‐C, which is absolutely required for lymphangiogenesis.12, 13, 14, 15 Nevertheless, VEGF‐D can compensate for the loss of VEGF‐C for the sprouting of lymphatics,16 and it appears to have a higher angiogenic potential than VEGF‐C.17, 18

Recent basic research suggests the importance of the lymphatic vasculature and VEGF‐C/VEGF‐D signaling as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular diseases.8, 19, 20 Lymphatic vessels play an important role in reverse cholesterol transport, a pathway responsible for cholesterol mobilization from peripheral tissues to the liver for excretion, lipoprotein metabolism, and atherosclerotic plaque formation.21, 22, 23 VEGF‐D is an important modifier of lipoprotein metabolism, and it is essential for the metabolism and hepatic uptake of chylomicrons.24 Treatment with VEGF‐C after myocardial infarction induces lymphangiogenesis, reduces fluid retention, facilitates inflammatory cell clearance in the cardiac tissue, and improves cardiac function.25, 26 Adenoviral administered VEGF‐D induces angiogenesis in pig myocardium,27 and mature VEGF‐D is being tested for treating refractory angina in humans.28

Recent observational studies have suggested that circulating levels of VEGF‐D are associated with the incidence of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic stroke.29, 30 Although the origin of circulating VEGF‐D levels is unclear, an elevated VEGF‐D level may represent an adaptation to the demands of the lymphatic system to remove excess fluid from the extravascular space of the lungs and peripheral tissues.29

We reported that the serum level of VEGF‐C is significantly associated with dyslipidemia, a causative risk factor as well as a therapeutic target of cardiovascular disease.31 We also demonstrated that the serum level of VEGF‐C is inversely and independently associated with all‐cause mortality in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease (CAD); there seems to be a non‐linear threshold of VEGF‐C levels at around the 25th percentile for the risk of mortality, suggesting a phenomenon in which a subset of patients are relatively “VEGF‐C deficient,” and that VEGF‐C and the lymphatic system have critical roles in the maintenance of homeostasis.32 VEGF‐D may have distinct relationships with mortality and cardiovascular events in those patients.

We thus investigated the prognostic and predictive value of VEGF‐D in a large‐scale, multicenter prospective cohort study of patients with suspected or known CAD undergoing elective coronary angiography.

Methods

Study Population

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. The present study was a subanalysis of the ANOX (Development of Novel Biomarkers Related to Angiogenesis or Oxidative Stress to Predict Cardiovascular Events) study. The main analysis results of the ANOX study have been described.32 In brief, patients with suspected or known CAD (1624 men and 794 women; mean age, 70.6 years old) undergoing elective coronary angiography were recruited to determine the predictive value of possible novel biomarkers for mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (see details of the entire cohort of the ANOX study in Table 1 and Table S1 in the report by Wada et al)32 The ANOX study group consists of 15 National Hospital Organization (NHO) institutions across Japan, and the present study was conducted by nationally certified cardiologists.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Incidence of Events According to the Quartiles of VEGF‐D

| Baseline Characteristics and Incidence of Events | Quartile 1 (N=607) | Quartile 2 (N=606) | Quartile 3 (N=604) | Quartile 4 (N=601) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.5 (10.9) | 70.3 (10.4) | 71.6 (10.3) | 72.0 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Male | 390 (64.3) | 415 (68.5) | 413 (68.4) | 406 (67.6) | 0.354 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 25.0 (3.9) | 24.1 (3.9) | 24.1 (3.7) | 23.7 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Obesityb | 290 (47.8) | 225 (37.1) | 227 (37.6) | 194 (32.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 439 (72.3) | 451 (74.4) | 463 (76.7) | 490 (81.5) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 376 (61.9) | 380 (62.7) | 366 (60.6) | 344 (57.2) | 0.219 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 213 (35.1) | 277 (45.7) | 274 (45.4) | 323 (53.7) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 94 (15.5) | 103 (17.0) | 106 (17.6) | 125 (20.8) | 0.101 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 70 (18) | 68 (20) | 63 (21) | 52 (26) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney diseasec | 166 (27.4) | 202 (33.3) | 269 (44.5) | 362 (60.2) | <0.001 |

| Gensini score, median (IQR)d | 11.0 (2.0–31.5) | 10.5 (2.5–31.0) | 12.8 (2.0–37.0) | 14.0 (3.3–46.8) | 0.011 |

| Obstructive coronary artery disease | 334 (55.0) | 340 (56.1) | 353 (58.4) | 365 (60.7) | 0.188 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 85 (14.0) | 82 (13.5) | 94 (15.6) | 93 (15.5) | 0.673 |

| Previous stroke | 76 (12.5) | 84 (13.9) | 102 (16.9) | 91 (15.1) | 0.168 |

| Previous heart failure hospitalization | 28 (4.6) | 42 (6.9) | 56 (9.3) | 127 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 30 (4.9) | 48 (7.9) | 81 (13.4) | 102 (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Malignancies | 48 (7.9) | 58 (9.6) | 70 (11.6) | 50 (8.3) | 0.119 |

| Anemiae | 136 (22.4) | 172 (28.4) | 249 (41.2) | 325 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drug use | 482 (79.4) | 475 (78.4) | 497 (82.3) | 513 (85.4) | 0.008 |

| Statin use | 341 (56.2) | 321 (53.0) | 284 (47.0) | 276 (45.9) | 0.001 |

| Aspirin use | 363 (59.8) | 347 (57.3) | 328 (54.3) | 302 (50.3) | 0.006 |

| NT‐proBNP, median (IQR), pg/mL | 91 (45 to 215) | 140 (62 to 393) | 248 (100 to 787) | 746 (183 to 2282) | <0.001 |

| cTnI, median (IQR), pg/mL | 0.0 (0.0 to 4.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 5.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 11.0) | 6.0 (0.0 to 31.0) | <0.001 |

| hs‐CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 0.9 (0.4 to 3.1) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.5) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.4) | 1.1 (0.3 to 3.5) | 0.037 |

| VEGF‐C, mean (SD), pg/mL | 3890 (1455) | 3754 (1518) | 3478 (1456) | 3224 (1389) | <0.001 |

| VEGF‐D, median (IQR), pg/mL | 142 (98 to 168) | 250 (220 to 277) | 389 (347 to 441) | 730 (596 to 988) | <0.001 |

| Incidence of events, no. (/1000 person‐years) | |||||

| All‐cause death | 39 (22.1) | 45 (25.6) | 60 (34.9) | 110 (67.5) | … |

| Cardiovascular death | 11 (6.2) | 14 (8.0) | 17 (9.9) | 46 (28.2) | … |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | 7 (4.1) | 4 (2.5) | … |

| Stroke | 15 (8.6) | 17 (9.8) | 16 (9.4) | 21 (13.0) | … |

| First MACEf | 28 (16.1) | 35 (20.3) | 38 (22.4) | 64 (39.9) | … |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. The quartiles of VEGF‐D levels were as follows: quartile 1, ≤194.7; quartile 2, 194.8 to 303.3; quartile 3, 303.4 to 500; quartile 4, >500 pg/mL. cTnI indicates contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin I; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; VEGF‐C, vascular endothelial growth factor C; and VEGF‐D, vascular endothelial growth factor D.

The P value represents a comparison of the differences among VEGF‐D quartiles by Kruskal‐Wallis and χ2 tests.

Obesity is defined as the body mass index of 25 or more.

Chronic kidney disease is defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The Gensini score represents the angiographic severity of coronary artery disease employing a nonlinear points system for degree of luminal narrowing.

Anemia is defined as a hemoglobin level of less than 13 g/dL in men and less than 12 g/dL in women.

The MACE is defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke.

Between January 2010 and November 2013, a total of 2513 patients were consecutively enrolled. After the exclusion of 26 patients who did not provide blood samples and 69 patients who withdrew consent, a total of 2418 patients were eligible. Data on the patients’ demographic characteristics, smoking status, medical history, and medication use were collected from medical records. The presence of obstructive CAD was assessed using a modified American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology classification.33 The severity of CAD was quantified using the Gensini score.34 The submitted data were examined for completeness and accuracy by the coordinating center (Clinical Research Institute, Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan), and data queries were sent to the study sites. The study was approved by the central ethics committee of the NHO headquarters and each institution's ethical committee. All of the patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Outcomes and Follow‐Up

The primary outcome was all‐cause death. The secondary outcomes were cardiovascular death and MACE defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The patients were monitored over 3 years (1080 days) for the occurrence of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and/or MACE. The follow‐up was performed by personnel blinded to the biomarker data through medical record/chart reviews, a survey letter, and/or telephone interviews.

Sudden death resulting from an unknown but presumed cardiovascular cause in high‐risk patients was included in cardiovascular death. All deaths and MACE were recorded in the official medical chart of the hospitals where the patients received care. The reported deaths, myocardial infarctions, and strokes were reviewed and adjudicated by the expert committee (three independent and blinded cardiologists). The follow‐up continued even after nonfatal myocardial infarction and/or nonfatal stroke had occurred. At the end of the follow‐up (day 1080), the survival status and detailed information about MACE were available in 2400 patients (99.3%), and 18 patients (0.7%) were lost to follow‐up.

Exposures, Sample Collection, and Biomarker Measurement

The predictor of this subanalysis was the patients’ serum levels of VEGF‐D. Fasting blood samples for serum were collected from the arterial catheter sheath at the beginning of each patient's coronary angiography before a heparinized saline flush. The serum was stored at −80°C for a mean of 4 years until it was assayed for VEGF‐D after one freeze‐thaw cycle. The serum VEGF‐D level was measured with a specific, commercially available, ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The sensitivity of the assay for VEGF‐D was 11.4 pg/mL. The inter‐/intra‐assay coefficients of variation (CV) of the ELISA for VEGF‐D were ≤8%/<7%. There is no significant cross‐reactivity or interference between the VEGF‐D ELISA and human VEGF‐C up to 50 ng/mL. The assays were performed by an investigator blinded to the sources of the samples.

The details of the assays for VEGF‐C, NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide), cTnl (contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin‐I), and hs‐CRP (high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein) are described elsewhere.32 Briefly, the serum levels of VEGF‐C and hs‐CRP were measured with specific, commercially available ELISA kits according to the manufacturers’ instructions (for VEGF‐C: Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; for hs‐CRP: CycLex, MBL, Nagano, Japan). The inter‐/intra‐assay CV of ELISA for VEGF‐C and hs‐CRP were <9%/<7% and <6%/<4%, respectively. The serum levels of NT‐proBNP were measured using a validated, sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Serum cTnI was measured with the ADVIA Centaur Troponin I Ultra assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA). The sensitivities of the assays for VEGF‐C and hs‐CRP were 4.6 and 28.6 pg/mL, respectively. The sensitivity of the assay for NT‐proBNP was 5 pg/mL, and the assay CV at values of the measuring range (5–35 000 pg/mL) was <10%. The sensitivity of the assay for cTnI was 6 pg/mL, and the assay CV at the 99th percentile reference value of 40 pg/mL (potential range, 20–60 pg/mL) was <10%.

Statistical Analysis

We divided the patients into quartiles according to their baseline VEGF‐D levels. The VEGF‐D values for each quartile can be found in the footnote of Table 1. These data were compared among the quartiles of VEGF‐D for differences using the Kruskal‐Wallis and χ2 tests. The relationships between either VEGF‐D or VEGF‐C and other variables were assessed in simple and stepwise multiple linear regression analyses. Stepwise variable selection was performed in a forward direction with the Bayesian information criterion. Because VEGF‐D, the Gensini score, NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hsCRP were normally distributed after logarithmic transformation, the logarithms of these parameters were used in the linear regression analyses. The relationships between the baseline VEGF‐D level and the outcomes were investigated with the use of Cox proportional hazard regression in four sets of models: models adjusted for traditional risk factors (age, sex, body mass index [BMI], hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and current smoking); models adjusted for possible clinical confounders (traditional risk factors and other possible clinical confounders of estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], the Gensini score, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, previous heart failure hospitalization, malignancies, anemia [defined as a hemoglobin level below 13 g/L in men and 12 g/L in women], antihypertensive drug use, statin use, and aspirin use); models adjusted for possible clinical confounders and established cardiovascular biomarkers (NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hs‐CRP for 1‐SD increase); and models adjusted for possible clinical confounders, established cardiovascular biomarkers, and VEGF‐C (for 1‐SD increase).

We evaluated the incremental predictive performance of biomarkers by calculating changes in the C‐statistic, continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI), and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) metrics.35 We assessed the model calibration by comparing predicted probabilities with observed probabilities. A residual analysis was used to assess model fit.

We also performed stratified analyses to examine the association between the serum VEGF‐D level and the risk of all‐cause death. All statistical tests were two sided, and P<0.05 were considered significant. Because all analyses were considered exploratory, the P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 23.0 (IBM Japan, Tokyo), JMP13 (SAS, Cary, NC), and R, ver. 3.5.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Additional details are described elsewhere.32

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The median level of VEGF‐D was 303.3 pg/mL (interquartile range, 194.7 to 500 pg/mL) for all the patients. The distribution of VEGF‐D levels in the entire patient cohort is shown in Figure S1. The baseline characteristics of the patients divided into the quartiles of VEGF‐D levels are shown in Table 1 and Table S1. The higher quartiles of VEGF‐D were significantly associated with older age, lower BMI, lower rate of obesity, higher rates of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, lower eGFR, higher rates of chronic kidney disease (CKD), previous heart failure hospitalization, atrial fibrillation, and anemia and lower rates of statin use and aspirin use. In addition, higher quartiles of VEGF‐D were significantly associated with higher levels of NT‐proBNP and cTnI but not with higher levels of hs‐CRP. Interestingly, the quartiles of VEGF‐D were significantly and inversely associated with the VEGF‐C level (β, −227; standard error of the mean, 26; P<0.001). Moreover, the gap between VEGF‐D and VEGF‐C levels becomes more narrow with increasing quartiles of VEGF‐D, whereas the sum of VEGF‐D and VEGF‐C is similar across the quartiles of VEGF‐D (Table S1). These findings might suggest that VEGF‐D is upregulated to make up for the loss of VEGF‐C. The scatterplot between VEGF‐D and VEGF‐C in the entire patient cohort is shown in Figure S2.

The correlations of VEGF‐D or VEGF‐C (as continuous variables) with other variables are shown in Tables S2 and S3. Stepwise regression analyses revealed that independent determinants of VEGF‐D were dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, current smoking, eGFR, anemia, statin use, NT‐proBNP, and hs‐CRP, whereas those of VEGF‐C were age, male sex, eGFR, anemia, NT‐proBNP, and hs‐CRP.

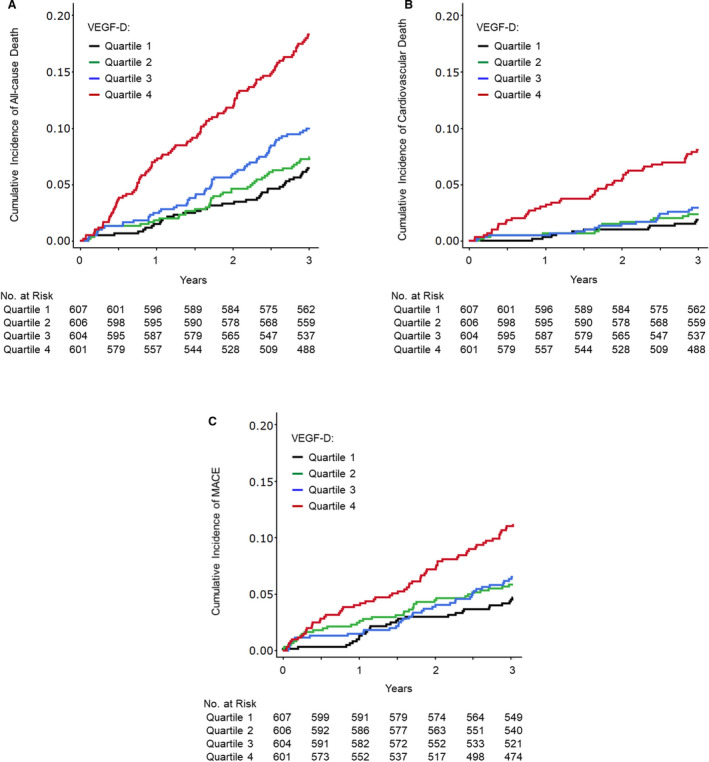

Incidence of Outcomes

As described in the ANOX study,32 254 patients died from any cause (88 cardiovascular and 166 noncardiovascular deaths), and 165 developed first MACE (21 myocardial infarction, 69 stroke, and 75 cardiovascular deaths) during the 3‐year follow‐up. Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE according to the quartiles of VEGF‐D levels. The highest quartile of VEGF‐D had the greatest risks of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE. Notably, there seems to be a step‐by‐step increase in the risk of all‐cause death according to the quartiles of VEGF‐D. The incidence of outcomes according to the quartiles of VEGF‐D levels is summarized in Table 1. Figure S3 shows the cumulative incidence of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE according to the quartiles of VEGF‐D levels in patients in the lowest quartile of VEGF‐C (≤ 25th percentile) and those in the three higher quartiles of VEGF‐C (>25th percentile). Importantly, even in patients with the lowest VEGF‐C level (≤ 25th percentile), the highest quartile of VEGF‐D seemed to confer the greatest risks of all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of all‐cause death (A), cardiovascular death (B), and major adverse cardiovascular events (C) according to the serum VEGF‐D level at baseline.

Follow‐up results are truncated after 3 years. MACE indicates major adverse cardiovascular events; and VEGF‐D, vascular endothelial growth factor D.

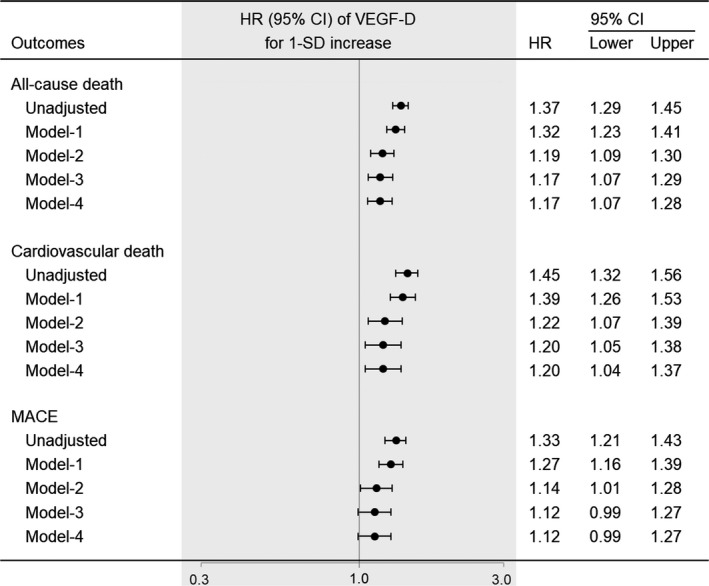

Multivariate Cox Regression Analyses

After adjustment for traditional risk factors (ie, age, sex, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and current smoking), the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE (model 1, Figure 2). After the additional adjustment for other possible clinical confounders (ie, eGFR, the Gensini score, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, previous heart failure hospitalization, malignancies, anemia, antihypertensive drug use, statin use, and aspirin use), the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACE (model 2, Figure 2). Even after additional adjustment for established cardiovascular biomarkers (NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hs‐CRP), the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death and cardiovascular death, but not with MACE (model 3, Figure 2). Importantly, after additional adjustment for VEGF‐C, the VEGF‐D level was still significantly associated with all‐cause death and cardiovascular death but not with MACE (model 4, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hazard ratios for all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and major adverse cardiovascular events according to VEGF‐D levels.

Values are for 1‐standard deviation increase. The data were adjusted for the following variables: model‐1, age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and current smoker; model‐2, model‐1 plus eGFR, the Gensini score, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, previous heart failure hospitalization, malignancies, anemia, antihypertensive drug use, statin use, and aspirin use; model‐3, model‐2 plus NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hs‐CRP; model‐4, model‐3 plus VEGF‐C. The biomarkers were modeled as continuous variables. cTnl indicates contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin‐I; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal‐pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; and VEGF‐D, vascular endothelial growth factor D.

Even in the 1717 patients with no history of CAD (ie, those with suspected CAD), the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death (n=161, hazard ratio [HR] 1.20, 95% CI, 1.08–1.34), and cardiovascular death (n=50, HR 1.21, 95% CI, 1.03–1.41) but not with MACE (n=104, HR 1.15, 95% CI, 0.999–1.32) after adjusting for possible clinical confounders. On the other hand, in the 711 patients with a history of (ie, known) CAD, the VEGF‐D level was also significantly associated with all‐cause death (n=93, HR 1.26, 95% CI, 1.07–1.50), and cardiovascular death (n=38, HR 1.38, 95% CI, 1.003–1.91) but not with MACE (n=61, HR 1.19, 95% CI, 0.91–1.55) after adjustment for possible clinical confounders.

Discrimination, Reclassification, and Calibration

The C‐statistics of the model with possible clinical confounders (base model) were 0.789 for all‐cause death, 0.817 for cardiovascular death, and 0.733 for MACE (Table 2). The C‐statistics of single biomarkers are also shown in Table 2. The combination of established cardiovascular biomarkers (NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hs‐CRP) significantly improved the prediction of all‐cause death but not that of cardiovascular death or MACE (Table 2). Notably, the addition of the VEGF‐D to the model with possible clinical confounders and established cardiovascular biomarkers significantly improved the prediction of all‐cause death (P=0.02 for NRI, P=0.02 for IDI) but not that of cardiovascular death (P=0.07 for NRI, P=0.21 for IDI) or MACE (P=0.47 for NRI, P=0.13 for IDI) (Table 2). Moreover, the addition of both VEGF‐D and VEGF‐C to the model with possible clinical confounders and established cardiovascular biomarkers further improved the prediction of all‐cause death (P<0.001 for NRI, P=0.004 for IDI) but not that of cardiovascular death or MACE. Calibration of the models in Table 2 showed no evidence of lack of fit.

Table 2.

Model Performance Measures for All‐Cause Death, Cardiovascular Death, and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

| Risk Factors and Biomarkers | C Statistics | ∆C Statistics | Continuous NRI, 95% CI | P Value | IDI, 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause death | ||||||

| Base modela | 0.789 | … | … | … | ||

| NT‐proBNP | 0.722 | … | … | … | ||

| cTnI | 0.656 | … | … | … | ||

| hs‐CRP | 0.641 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐C | 0.656 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐D | 0.641 | … | … | … | ||

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRPb | 0.803 | 0.015 | 0.385 (0.256 to 0.575) | <0.001 | 0.017 (0.006 to 0.028) | 0.003 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Cc | 0.806 | 0.003 | 0.176 (0.047 to 0.305) | 0.01 | 0.003 (0.0003 to 0.006) | 0.08 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Dc | 0.807 | 0.004 | 0.161 (0.032 to 0.290) | 0.02 | 0.008 (0.002 to 0.014) | 0.02 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐C+VEGF‐Dc | 0.809 | 0.006 | 0.287 (0.158 to 0.416) | <0.001 | 0.013 (0.003 to 0.017) | 0.004 |

| Cardiovascular death | ||||||

| Base modela | 0.817 | … | … | … | ||

| NT‐proBNP | 0.788 | … | … | … | ||

| cTnI | 0.715 | … | … | … | ||

| hs‐CRP | 0.589 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐C | 0.653 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐D | 0.676 | … | … | … | ||

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRPb | 0.823 | 0.007 | 0.039 (−0.174 to 0.251) | 0.72 | 0.008 (−0.006 to 0.022) | 0.25 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Cc | 0.823 | −0.001 | 0.239 (0.031 to 0.448) | 0.02 | 0.002 (−0.0001 to 0.004) | 0.07 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Dc | 0.826 | 0.003 | 0.194 (−0.018 to 0.407) | 0.07 | 0.007 (−0.004 to 0.019) | 0.21 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐C+VEGF‐Dc | 0.826 | 0.002 | 0.078 (−0.135 to 0.290) | 0.47 | 0.009 (−0.003 to 0.02) | 0.13 |

| Major adverse cardiovascular events | ||||||

| Base modela | 0.733 | … | … | … | ||

| NT‐proBNP | 0.703 | … | … | … | ||

| cTnI | 0.648 | … | … | … | ||

| hs‐CRP | 0.584 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐C | 0.592 | … | … | … | ||

| VEGF‐D | 0.607 | … | … | … | ||

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRPb | 0.740 | 0.007 | 0.131 (−0.025−0.287) | 0.101 | 0.009 (−0.003−0.020) | 0.14 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Cc | 0.740 | 0.000 | 0.041 (−0.117 to 0.199) | 0.613 | 0.000 (−0.0001 to 0.0002) | 0.57 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐Dc | 0.741 | 0.001 | 0.060 (−0.097 to 0.216) | 0.456 | 0.002 (−0.002 to 0.005) | 0.38 |

| Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP+VEGF‐C+VEGF‐Dc | 0.741 | 0.001 | 0.050 (−0.106 to 0.207) | 0.530 | 0.002 (−0.002 to 0.005) | 0.38 |

Follow‐up results are truncated after 3 years. The biomarkers were modeled as continuous variables (for 1‐SD increase). The ∆C statistic, continuous NRI and IDI show the change in model performance from “Base model” or “Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP.” cTnl indicates contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin I; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; NRI, net reclassification improvement; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; VEGF‐C, vascular endothelial growth factor C; and VEGF‐D, vascular endothelial growth factor D.

The base model is based on age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, current smoking, eGFR, the Gensini score, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, previous heart failure hospitalization, atrial fibrillation, malignancies, anemia, antihypertensive drug use, statin use, and aspirin use.

Evaluated the change of model performance from the “Base model.”

Evaluated the change of model performance from the “Base model+NT‐proBNP+cTnI+hs‐CRP.”

Multivariate‐Adjusted Stratified Analyses

In the multivariate‐adjusted stratified analyses, the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death regardless of sex and the presence/absence of dyslipidemia, obstructive CAD, previous stroke, previous heart failure hospitalization, atrial fibrillation, anemia, statin use, aspirin use, or the lowest VEGF‐C level (≤25th percentile) (Figure S4). The VEGF‐D level was not significantly associated with all‐cause death in the patients under 75 years old, those with obesity (BMI≥25), those without hypertension, those without diabetes mellitus, current smokers, those without CKD, those with previous myocardial infarction, those with malignancies, or those without antihypertensive drug use. Notably, the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death in the patients over 75 years old.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort of patients with suspected or known CAD, we identified a significant association between the serum VEGF‐D level and all‐cause mortality, in sharp contrast to the inverse correlation between the serum VEGF‐C level and all‐cause mortality.32 This association is independent of possible clinical confounders, the cardiovascular biomarkers (NT‐proBNP, cTnI, hs‐CRP), and VEGF‐C. The strengths of our investigation include the use of a well‐established VEGF‐D assay that is already in clinical use for the diagnosis and disease monitoring of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), the large sample size, the multicenter prospective design, and a high follow‐up rate (99.3%).8, 36 The Kaplan‐Meier analysis showed a step‐by‐step increase in the risk of all‐cause mortality according to quartiles of VEGF‐D; it may be advantageous for the staged risk prediction compared with an abrupt change in the risk of all‐cause mortality at around the 25th percentile of VEGF‐C levels.32 Although it has already been reported that the VEGF‐D level is associated with heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke,29, 30 we demonstrated that even in patients without a history of heart failure, those without atrial fibrillation, and those without a history of stroke, the VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death after adjustment for possible clinical confounders (Figure S4). Taken together, the results of our analyses demonstrate that the measurement of the serum VEGF‐D level may provide prognostic information about all‐cause mortality beyond these factors in clinical settings.

Our study subjects included both patients with a history of (ie, known) CAD and those with no history of (ie, suspected) CAD, and the former patients would be at much higher risk of suffering the studied outcomes. Similarly, our study subjects included both patients with and those without obstructive CAD. However, a significant association between the VEGF‐D level and all‐cause death after adjustment for possible clinical confounders did not depend on the presence/absence of a history of CAD or obstructive CAD.

In our stratified analyses, we did not observe significant associations between the VEGF‐D level and all‐cause death in the patients under 75 years old, those with obesity, those without hypertension, those without diabetes mellitus current smokers, those without CKD, those with previous myocardial infarction, those with malignancies, or those without antihypertensive drug use. In addition, the use of the VEGF‐D level did not significantly improve the prediction of cardiovascular death over the model with possible clinical confounders and cardiovascular biomarkers in the entire cohort. However, we had limited statistical power to test these findings. Longer follow‐ups are needed to determine whether or not VEGF‐D represents a distinct cardiovascular risk factor and to establish the relationships between the VEGF‐D level and specific causes of death.

In the ANOX subgroups of patients with a history of heart failure hospitalization, those with atrial fibrillation, and those with a history of stroke, the serum VEGF‐D level was significantly associated with all‐cause death after adjusting for possible clinical confounders (Figure S4). Hence, VEGF‐D may serve not only as a predictor of the incidence of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic stroke but also as a prognostic biomarker in patients with chronic heart failure, those with atrial fibrillation, and those with a history of stroke. Larger‐scale cohort studies including ours (the PREHOSP‐CHF [Development of Novel Biomarkers to Predict Rehospitalization in Chronic Heart Failure] study, UMIN000021657) are needed to confirm these findings.

Both high VEGF‐D and low VEGF‐C levels (as continuous variables) were independently correlated with eGFR, anemia, NT‐proBNP, and hs‐CRP, indicating that these two factors are involved in renal anemia, heart failure, and inflammation. On the other hand, VEGF‐D, but not VEGF‐C, was independently correlated with dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and current smoking, suggesting that VEGF‐D is more closely associated with lifestyle‐related risk factors than VEGF‐C. In a future study, it would be of interest to examine whether lifestyle modification can decrease circulating levels of VEGF‐D.

VEGF‐D is a validated diagnostic biomarker of LAM, which is a progressive, cystic lung disease in women. LAM is associated with an inappropriate activation of mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, which regulates cellular growth and lymphangiogenesis.8, 36, 37 LAM is caused by inactivating mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) genes, resulting in the expression of VEGF‐D (and VEGF‐C) and extensive pulmonary lymphangiogenesis.36 Rapamycin (also called sirolimus) inhibited mTOR signaling, stabilized lung function, and reduced the serum VEGF‐D level in patients with LAM.36, 37 However, the sources and mechanisms of the serum VEGF‐D upregulation in LAM patients remain elusive.36

The gene encoding VEGF‐D is expressed in a range of tissues during development and in adult tissues, with prominent expression in lung and skin.8 In adult human tissues, VEGF‐D is produced mostly in the heart, lung, skeletal muscle, colon, and small intestine.2 As described,29 it is possible that VEGF‐D represents an adaptation to the demands of the lymphatic system to remove excess fluid from the extravascular space of lungs and peripheral tissues. In addition to the role of VEGF‐D in lymphangiogenesis, the circulating VEGF‐D level could be associated with cardiac angiogenesis. A significant upregulation of cardiac VEGF‐D after myocardial infarction has been demonstrated, implicating the involvement of VEGF‐D in cardiac fibrogenesis to promote repair and remodeling.38, 39 An elevated VEGF‐D level might therefore — at least in part — reflect increased cardiac angiogenesis, fibrogenesis, and remodeling. Given the inverse correlation between VEGF‐C and VEGF‐D, VEGF‐D may be upregulated to compensate for the insufficient production of VEGF‐C in response to the increasing demands of either or both of lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis.

A recent animal study demonstrated that VEGF‐D, as well as VEGF‐C, is abundantly present in renal tubules under baseline conditions, and that following kidney injury, its expression pattern is significantly altered, and serum and urine levels of VEGF‐D (and VEGF‐C) are increased.40 However, in the present study, as eGFR declined, the VEGF‐C level decreased and the VEGF‐D level increased. The morphological hallmarks of CKD are tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis,41 in which transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts is involved.42 Since VEGF‐D serves as a profibrogenic mediator by stimulating myofibroblast growth, migration, and collagen synthesis,39 VEGF‐D may play a role in the development of interstitial fibrosis during CKD progression, just as in cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Given the inverse correlation of VEGF‐C and VEGF‐D levels with renal function, it would be interesting for future studies to examine whether VEGF‐C and VEGF‐D levels are associated with proximal tubular mass and interstitial fibrosis, respectively. Further investigation is necessary to elucidate the sources of VEGF‐D and the molecular mechanisms that regulate the circulating levels of VEGF‐D.

Limitations

First, the patients’ blood samples were drawn from the arterial sheath. Because VEGF‐D is one of the vascular and lymphatic endothelial cell‐specific ligands, it is possible that its concentrations in the arterial and venous circulation differ. In our preliminary data (n=40), the VEGF‐D levels in sera from the arterial sheath were closely correlated with those from the peripheral vein before cardiac catheterization (β, 0.863; standard error of the mean, 0.034; P<0.001). However, to validate VEGF‐D's potential to be used more widely in risk prediction, other cohort studies using peripheral venous blood samples are necessary, such as our EXCEED‐J (Establishment of the Method to Extract a High Risk Population Employing Novel Biomarkers to Predict Cardiovascular Events in Japan) study (UMIN000018807). Second, the serum samples had been frozen for a mean of 4 years. Thus, there is a risk that the absolute VEGF‐D level was affected by being derived from frozen, rather than fresh, samples. Future studies are necessary to determine the optimal cutoff point for the VEGF‐D level in fresh samples. Third, we did not measure VEGF‐D levels repeatedly during the follow‐up. It would be interesting for future studies that use repeated measurements of VEGF‐D levels, including our own PREHOSP‐CHF study, to investigate the relationship between the change in VEGF‐D levels and the risk of mortality. Fourth, we used a contemporary sensitive troponin‐I assay but not a high‐sensitivity troponin I or T assay. Fifth, we had no collected data of cardiovascular imaging such as echocardiography, cardiovascular magnetic resonance, computed tomography, intravascular ultrasound/optical coherence tomography, and nuclear imaging. The elucidation of the relationship between the VEGF‐D level and these cardiac imaging data will provide valuable insights into the mechanistic role of VEGF‐D. Sixth, we had no collected data of a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is also one of the possible clinical confounders. Seventh, this was an observational study, and other unmeasured confounding factors may have existed. Finally, because the ANOX study cohort is exclusively Asian individuals with suspected or known CAD, our results may not be generalizable to general Asian populations, or to other ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Nevertheless, our results clearly demonstrate that an elevated serum VEGF‐D value was independently associated with all‐cause mortality beyond the possible clinical confounders, cardiovascular biomarkers (NT‐proBNP, cTnI, and hs‐CRP), and VEGF‐C in patients with suspected or known CAD undergoing elective coronary angiography. This association was especially pronounced in patients over 75 years old.

Affiliations

From the Division of Translational Research (H.W., T.U., D.T., M.W., M.L., N.M., M.I., M.A., K.H.), Department of Cardiology (M. Iguchi, N.M., M. Ishii, M. Abe, M. Akao), Department of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Hypertension, Clinical Research Institute (H.Y., T. Kusakabe, N.S.‐A.), and Clinical Research Institute (A.Y., A.S.), National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan; Department of Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization Saitama Hospital, Wako, Japan (M. Suzuki); Institute for Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center, Kure, Japan (M.M.); Division of Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization Yokohama Medical Center, Yokohama, Japan (Y.A.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Sendai Medical Center, Sendai, Japan (T.S.); Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, National Hospital Organization Kanazawa Medical Center, Kanazawa, Japan (S.S.); Division of Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization Hakodate National Hospital, Hakodate, Japan (K.Y.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kobe Medical Center, Kobe, Japan (M. Shimizu); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Ehime Medical Center, Toon, Japan (J.F.); Division of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Hokkaido Medical Center, Sapporo, Japan (T.T.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Sagamihara National Hospital, Sagamihara, Japan (Y.M.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center, Fukuoka, Japan (T.N.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Kumamoto Medical Center, Kumamoto, Japan (K.F.); Department of Cardiology, National Hospital Organization Okayama Medical Center, Okayama, Japan (H.M.); Department of Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization Tochigi Medical Center, Utsunomiya, Japan (T. Kato); Intensive Care Unit (T.U.), and Department of Acute Care and General Medicine (D.T.), Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan; Division of Community and Family Medicine, Jichi Medical University, Shimotsuke, Japan (K.K.).

Sources of Funding

The ANOX study is supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Clinical Research from the National Hospital Organization in Japan.

Disclosures

H. Wada reports a patent‐pending biomarker and method to predict all‐cause death, cardiovascular death, and cardiovascular events (Patent application No. JP P2018‐206995). The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Tables S1–S3 Figures S1–S4

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Shuichi Ura who substantially contributed to this work but passed away before this manuscript was drafted. We also thank the other members, cooperators, and participants of the ANOX study for their valuable contributions.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015761 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015761.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

References

- 1. Lohela M, Bry M, Tammela T, Alitalo K. VEGFs and receptors involved in angiogenesis versus lymphangiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Achen MG, Jeltsch M, Kukk E, Mäkinen T, Vitali A, Wilks AF, Alitalo K, Stacker SA. Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF‐D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:548–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stacker SA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Fox SB, Achen MG. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic vessel remodelling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:159–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng W, Aspelund A, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenic factors, mechanisms, and applications. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:878–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duong T, Koltowska K, Pichol‐Thievend C, Le Guen L, Fontaine F, Smith KA, Truong V, Skoczylas R, Stacker SA, Achen MG, et al. VEGFD regulates blood vascular development by modulating SOX18 activity. Blood. 2014;123:1102–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ober EA, Olofsson B, Mäkinen T, Jin SW, Shoji W, Koh GY, Alitalo K, Stainier DY. Vegfc is required for vascular development and endoderm morphogenesis in zebrafish. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davydova N, Harris NC, Roufail S, Paquet‐Fifield S, Ishaq M, Streltsov VA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Stacker SA, Achen MG. Differential receptor binding and regulatory mechanisms for the lymphangiogenic growth factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)‐C and ‐D. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:27265–27278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stacker SA, Achen MG. Emerging roles for VEGF‐D in human disease. Biomolecules. 2018;8:1 Available at: 10.3390/biom8010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kukk E, Lymboussaki A, Taira S, Kaipainen A, Jeltsch M, Joukov V, Alitalo K. VEGF‐C receptor binding and pattern of expression with VEGFR‐3 suggests a role in lymphatic vascular development. Development. 1996;122:3829–3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stacker SA, Williams RA, Achen MG. Lymphangiogenic growth factors as markers of tumor metastasis. APMIS. 2004;112:539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stacker SA, Baldwin ME, Achen MG. The role of tumor lymphangiogenesis in metastatic spread. FASEB J. 2002;16:922–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joukov V, Pajusola K, Kaipainen A, Chilov D, Lahtinen I, Kukk E, Saksela O, Kalkkinen N, Alitalo K. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF‐C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR‐3) and KDR (VEGFR‐2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1996;15:290–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang Y, Oliver G. Development of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:888–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karaman S, Detmar M. Mechanisms of lymphatic metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:922–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karkkainen MJ, Haiko P, Sainio K, Partanen J, Taipale J, Petrova TV, Jeltsch M, Jackson DG, Talikka M, Rauvala H, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Astin JW, Haggerty MJ, Okuda KS, Le Guen L, Misa JP, Tromp A, Hogan BM, Crosier KE, Crosier PS. Vegfd can compensate for loss of Vegfc in zebrafish facial lymphatic sprouting. Development. 2014;141:2680–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byzova TV, Goldman CK, Jankau J, Chen J, Cabrera G, Achen MG, Stacker SA, Carnevale KA, Siemionow M, Deitcher SR, et al. Adenovirus encoding vascular endothelial growth factor‐D induces tissue‐specific vascular patterns in vivo. Blood. 2002;99:4434–4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rissanen TT, Markkanen JE, Gruchala M, Heikura T, Puranen A, Kettunen MI, Kholová I, Kauppinen RA, Achen MG, Stacker SA, et al. VEGF‐D is the strongest angiogenic and lymphangiogenic effector among VEGFs delivered into skeletal muscle via adenoviruses. Circ Res. 2003;92:1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vuorio T, Tirronen A, Ylä‐Herttuala S. Cardiac lymphatics—a new avenue for therapeutics? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aspelund A, Robciuc MR, Karaman S, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Lymphatic system in cardiovascular medicine. Circ Res. 2016;118:515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martel C, Li W, Fulp B, Platt AM, Gautier EL, Westerterp M, Bittman R, Tall AR, Chen SH, Thomas MJ, et al. Lymphatic vasculature mediates macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1571–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim HY, Thiam CH, Yeo KP, Bisoendial R, Hii CS, McGrath KC, Tan KW, Heather A, Alexander JS, Angeli V. Lymphatic vessels are essential for the removal of cholesterol from peripheral tissues by SR‐BI‐mediated transport of HDL. Cell Metab. 2013;17:671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kutkut I, Meens MJ, McKee TA, Bochaton‐Piallat ML, Kwak BR. Lymphatic vessels: an emerging actor in atherosclerotic plaque development. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tirronen A, Vuorio T, Kettunen S, Hokkanen K, Ramms B, Niskanen H, Laakso H, Kaikkonen MU, Jauhiainen M, Gordts PLSM, et al. Deletion of lymphangiogenic and angiogenic growth factor VEGF‐D leads to severe hyperlipidemia and delayed clearance of chylomicron remnants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:2327–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klotz L, Norman S, Vieira JM, Masters M, Rohling M, Dubé KN, Bollini S, Matsuzaki F, Carr CA, Riley PR. Cardiac lymphatics are heterogeneous in origin and respond to injury. Nature. 2015;522:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henri O, Pouehe C, Houssari M, Galas L, Nicol L, Edwards‐Lévy F, Henry JP, Dumesnil A, Boukhalfa I, Banquet S, et al. Selective stimulation of cardiac lymphangiogenesis reduces myocardial edema and fibrosis leading to improved cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2016;133:1484–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rutanen J, Rissanen TT, Markkanen JE, Gruchala M, Silvennoinen P, Kivelä A, Hedman A, Hedman M, Heikura T, Ordén MR, et al. Adenoviral catheter‐mediated intramyocardial gene transfer using the mature form of vascular endothelial growth factor‐D induces transmural angiogenesis in porcine heart. Circulation. 2004;109:1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hartikainen J, Hassinen I, Hedman A, Kivelä A, Saraste A, Knuuti J, Husso M, Mussalo H, Hedman M, Rissanen TT, et al. Adenoviral intramyocardial VEGF‐DΔNΔC gene transfer increases myocardial perfusion reserve in refractory angina patients: a phase I/IIa study with 1‐year follow‐up. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2547–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borné Y, Gränsbo K, Nilsson J, Melander O, Orho‐Melander M, Smith JG, Engström G. Vascular endothelial growth factor D, pulmonary congestion, and incidence of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berntsson J, Smith JG, Johnson LSB, Söderholm M, Borné Y, Melander O, Orho‐Melander M, Nilsson J, Engström G. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor D is associated with atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke. Heart. 2019;105:553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wada H, Ura S, Kitaoka S, Satoh‐Asahara N, Horie T, Ono K, Takaya T, Takanabe‐Mori R, Akao M, Abe M, et al. Distinct characteristics of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor‐A and C levels in human subjects. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wada H, Suzuki M, Matsuda M, Ajiro Y, Shinozaki T, Sakagami S, Yonezawa K, Shimizu M, Funada J, Takenaka T, et al. VEGF‐C and mortality in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010355 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, McGoon DC, Murphy ML, Roe BB. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51:5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Pencina KM, Janssens AC, Greenland P. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:473–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nijmeh J, El‐Chemaly S, Henske EP. Emerging biomarkers of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCormack FX, Inoue Y, Moss J, Singer LG, Strange C, Nakata K, Barker AF, Chapman JT, Brantly ML, Stocks JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1595–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao T, Zhao W, Chen Y, Liu L, Ahokas RA, Sun Y. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms and receptor subtypes in the infarcted heart. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2638–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao T, Zhao W, Meng W, Liu C, Chen Y, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor‐D mediates fibrogenic response in myofibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;413:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zarjou A, Black LM, Bolisetty S, Traylor AM, Bowhay SA, Zhang MZ, Harris RC, Agarwal A. Dynamic signature of lymphangiogenesis during acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. Lab Invest. 2019;99:1376–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chevalier RL. The proximal tubule is the primary target of injury and progression of kidney disease: role of the glomerulotubular junction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F145–F161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takaori K, Nakamura J, Yamamoto S, Nakata H, Sato Y, Takase M, Nameta M, Yamamoto T, Economides AN, Kohno K, et al. Severity and frequency of proximal tubule injury determines renal prognosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2393–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Tables S1–S3 Figures S1–S4