Abstract

Background

The diet impact on cardiovascular diseases has been investigated widely, but the association between dietary patterns (DPs) and subclinical cardiovascular damage remains unclear. More informative DPs could be provided by considering metabolic syndrome components as intermediate markers. This study aimed to identify DPs according to generation and sex using reduced‐rank regression (RRR) with metabolic syndrome components as intermediate markers and assess their associations with intima‐media thickness, left ventricular mass, and carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity in an initially healthy population‐based family study.

Methods and Results

This study included 1527 participants from the STANISLAS (Suivi Temporaire Annuel Non‐Invasif de la Santé des Lorrains Assurés Sociaux) cohort fourth examination. DPs were derived using reduced‐rank regression according to generation (G1: age ≥50 years; G2: age <50 years) and sex. Associations between DPs and cardiovascular damage were analyzed using multivariable linear regression models. Although identified DPs were correlated between generations and sex, qualitative differences were observed: whereas only unhealthy DPs were found for both men generations, healthy DPs were identified in G2 (“fruity desserts”) and G1 (“fiber and w3 oil”) women. The “alcohol,” “fast food and alcohol,” “fried, processed, and dairy products,” and “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DPs in G1 and G2 men and in G1 and G2 women, respectively, were associated with high left ventricular mass (β [95% CI], 0.23 [0.10–0.36], 0.76 [0.00–1.52], 1.71 [0.16–3.26], and 1.80 [0.45–3.14]). The “alcohol” DP in G1 men was positively associated with carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity (0.22 [0.09–0.34]).

Conclusions

The DPs that explain the maximum variation in metabolic syndrome components had different associations with subclinical cardiovascular damage across generation and sex. Our results indicate that dietary recommendations should be tailored according to age and sex.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01391442.

Keywords: carotid intima‐media thickness, dietary patterns, generation, left ventricular mass, pulse‐wave velocity

Subject Categories: Diet and Nutrition, Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Using reduced‐rank regression with metabolic syndrome components as intermediate markers, we highlighted different dietary patterns across generation and sex.

Dietary patterns were differently associated with subclinical cardiovascular damage across generation and sex.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Dietary recommendations for cardiometabolic risk prevention should be tailored according to age and sex.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. The overall impact of diet on cardiovascular diseases have been studied widely, with the available evidence showing that a healthy dietary pattern (DP)—rich in fruits, vegetables, and nuts, or a Mediterranean‐style diet—lowers the risk of major cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease.1, 2 Conversely, a suboptimal Western‐type DP—rich in processed meat, sugar, or fast foods—is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease risk, and mortality.3, 4, 5

Measures of CV damage such as the carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity (cfPWV), carotid intima‐media thickness (cIMT), and left ventricular (LV) mass are strong predictors or surrogate markers of future cardiovascular diseases.6, 7, 8 Diet also seems to have an impact on cardiovascular damage. However, previous studies focusing on single foods or nutrients have produced inconsistent results, with the alcohol and carbohydrate intake being positively associated with cfPWV,9, 10 while dairy products had a negative association.11 The intakes of total and subtypes of fat have recently been associated with lower mortality, whereas a high carbohydrate intake was associated with a higher risk of all‐cause mortality.12

The association between alcohol consumption and cIMT remains unclear.13 Beyond these single‐food approaches, other studies have used more integrative methodologies that consider the whole diet by deriving DPs, with data‐driven methods such as principal‐components analysis or clustering being widely used.14 A DP characterized by a high consumption of alcohol and meat was found to be associated with cfPWV but not cIMT.15 The association between the Mediterranean‐diet score and LV mass was found to be negative16 or U‐shaped,17 whereas a Mediterranean‐style DP seems to reduce carotid atherosclerosis.18 A traditional DP characterized by a high intake of rye, potatoes, butter, sausages, milk, and coffee was found to be positively associated with cIMT.19

Numerous studies have further demonstrated a relation between metabolic syndrome (MetS) and cardiovascular damage.20, 21, 22 A recent meta‐analysis found that a healthy DP was associated with a lower prevalence of MetS and vice versa.23 A pathway between diet, MetS, and cardiovascular damage could therefore be hypothesized.

Reduced‐rank regression (RRR) is another data‐driven method developed in nutritional epidemiology to test specific hypotheses regarding a pathway between diet and disease.24 In contrast with principal‐components analysis, which produces a linear combination (factor) of food‐intake data that maximally explains the variation in food intake, the RRR method determines factors from food‐intake data that maximize the explained variation in the intermediate markers that are hypothesized to be related to a particular health outcome.24 Moreover, differences in DP according to sex or age have been found in other research fields, indicating the need to derive DPs separately in men versus women and in elderly versus younger adults.25, 26, 27, 28 However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has addressed the relations between diet and cardiovascular damage by deriving DPs separately according to sex and age.

We hypothesized that considering MetS components as intermediate markers and stratifying them by generation and sex in deriving DPs will allow us to identify more informative DPs and evidence refined associations between specific DPs and cardiovascular damage. To test our hypothesis, we took advantage of the familial STANISLAS (Suivi Temporaire Annuel Non‐Invasif de la Santé des Lorrains Assurés Sociaux) cohort that comprises 2 generations and for which extensive cardiovascular phenotyping has been performed.29

Our objective was to derive the DPs using RRR with MetS components as intermediate markers according to generation and sex, identify the differences between DPs according to generation and sex, and subsequently determine the relation between the identified DP and subclinical cardiovascular damage (ie, cfPWV, cIMT, and LV mass) in the familial STANISLAS cohort.

Subjects and Methods

Study Population

The STANISLAS cohort is a population‐based study of 1006 families that each comprise at least 2 parents and 2 children (4295 participants) from the Lorraine region (eastern France) recruited during 1993–1995 at the Center for Preventive Medicine. The participants were of French origin and free of acute or chronic disease. From 2011 to 2016, 1705 participants underwent their fourth examination. The STANISLAS study has been described in detail elsewhere.29 The present study focused on the 1695 participants who underwent the fourth examination and for whom data on food intake were available. After excluding 79 patients with missing data on health outcomes, 26 with a cardiovascular history (15 with myocardial infarction and 11 with heart failure), and 63 with a daily energy intake either below 1000 or above 5000 kcal, the present cross‐sectional analysis included 1527 participants (Figure S1). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics

The research protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Est III, Nancy, France) and all study participants gave written informed consent to participate.

Data Collection

Dietary assessment

Dietary intake was assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire.30 The participants reported their consumption frequency and portion size of 133 food items over the previous 3 months. The consumption frequency was reported using 6 levels in the questionnaire, ranging from “never or rarely” to “2 times or more a day.” The portion size of each food item was estimated using standard serving sizes and food models. Daily nutrient intakes were calculated in grams per day by multiplying the consumption frequency of each item by the nutrient content of selected portions. Nutritional data were extracted from the French food composition database established by the French Data Centre on Food Quality (Ciqual, last updated in 2013). To perform DP analysis, food items were aggregated into 41 food groups based on the similarity of their nutritional compositions (Table S1).

Carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity

The cfPWV was measured using the Complior device (Alam Medical, France) in a quiet room after at least 10 minutes of rest in the supine position according to the recommendations of the European Network for the Noninvasive Investigation of Large Arteries.29, 31, 32 Two sensors were placed simultaneously on the carotid artery and on the femoral artery. Two measurements were made, with cfPWV calculated as their mean. If the 2 measurements differed by >0.5 m/s, a third measurement was made, and the cfPWV was then calculated as the median of the 3 measurements. The onboard foot‐to‐foot algorithm based on the second‐derivative waveforms was used to determine the transit time. The carotid‐to‐femoral, carotid‐to‐sternal‐notch, and sternal‐notch‐to‐carotid distances were measured with a measuring tape. The distance used for cfPWV calculation was 0.8 times the direct carotid‐femoral distance. cfPWV was calculated as follows: distance divided by transit time.

Carotid intima‐media thickness

cIMT measurements were routinely performed by high‐resolution echo tracking. The noninvasive investigations were performed in a controlled environment at 22±1°C after 10 minutes of rest in the supine position. The carotid diameter, carotid distention, and cIMT were measured for the right common carotid artery. Four measurements were made per patient. Examinations were performed with a wall tracking system (ESOATE, Maastricht, The Netherlands) and/or the ART.LAB (ESAOTE) in immediate succession. The interdevice reproducibility and agreement of the measurements were excellent.

Left ventricular mass

Echocardiographic examinations of the subject in the left lateral decubitus position were performed by an experienced echocardiographer using a commercially available standard ultrasound scanner (Vivid E9, General Electric Medical Systems, Horten, Norway) with a 2.5‐MHz phased‐array transducer (M5S). The echo/Doppler examinations included exhaustive examinations in parasternal long‐ and short‐axis views and in the standard apical views.33, 34

All acquired images and media were stored on a secured network server as digital videos with unique identification numbers, and they were analyzed on a dedicated workstation (EchoPAC PC, version 110.1.0, GE Healthcare). We measured the septal wall thickness, posterior wall thickness, and LV internal diastolic diameter from the parasternal 2‐dimensional long‐axis view. These measurements were subsequently used in the cube‐function formula of the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines to calculate the LV mass,35 which was then indexed for height to 2.7 power.36

Covariates

A self‐reported questionnaire was used to collect demographic and socioeconomic information, such as age, sex, education level (categorized into low, intermediate, or high), and smoking status (categorized into yes or no), as well as information about disease history and treatment. Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire guidelines were followed to clean the data and calculate the weekly energy expenditure expressed in metabolic equivalent task minutes per week (www.IPAQ.ki.se).

Anthropometric measurements such as weight, height, and waist circumference (WC) were made during a clinical examination. Blood samples were collected, and the serum concentrations of the following biomarkers were measured: fasting glucose, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), and triglycerides.29 Office blood pressure was also measured,29 as was the 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure.37, 38 In brief, participants underwent 24‐hour recording of the ambulatory blood pressure using the Spacelabs 90207 ambulatory monitor (Spacelabs Medical), with the monitoring cuff placed around the nondominant arm. The blood pressure system was programmed to make measurements every 15 minutes from 6 am to 10 pm and every 30 minutes from 10 pm to 6 am.

Assessment of metabolic syndrome criteria

We defined MetS according to National Cholesterol Education Program ATP339 as the presence of ≥3 of the following components: elevated WC (>102 cm for men, >88 cm for women); elevated triglycerides (≥1.5 g/L) or treated by lipid‐lowering drugs; reduced HDL‐C (<0.4 g/L for men, <0.5 g/L for women); elevated office systolic blood pressure (SBP, ≥130 mm Hg) or elevated diastolic blood pressure (DBP, ≥85 mm Hg), or treated by antihypertensive drugs; or elevated glucose (≥1.10 g/L) or treated by antidiabetic drugs. Because it has been shown that different combinations of MetS components may be more or less strictly associated with subclinical vascular damage, such as pulse‐wave velocity, we focused in this article on all the components of MetS.40

Statistical Analysis

The study population was divided by generation (generation 1 [G1] comprised individuals aged ≥50 years, and generation 2 [G2] comprised their younger counterparts) and sex according to sociodemographic, biological, and clinical data. The results were expressed as mean±SD values for normally distributed quantitative variables and as median and interquartile range variables for the skewed variables. Frequencies were used to summarize qualitative variables. Differences between groups were assessed using the chi‐square test for categorical variables and ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test for continuous variables.

DPs were derived from the 41 standardized food groups using the RRR method.24 This method constructs uncorrelated linear combinations of food‐group intakes that maximize the explained variation in the intermediate variables that are hypothesized to be related to health outcomes. The following components of MetS were selected as intermediate continuous variables: WC, triglycerides, HDL‐C, glucose, SBP, and DBP. We performed the assessment using the 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure since this is more accurate in an RRR. The number of factors extracted from the RRR is determined by the number of intermediate markers (here, 6), and each factor is characterized by 41 factor loadings: 1 for each food group. Factor loadings represent the correlations of each food group with the DP score, where factor loadings with positive values indicate that the corresponding food groups are positively associated with the DP, and negative values indicate an inverse association. A larger factor loading value indicates that food group makes a greater contribution to the DP. DPs were derived independently according to generation and sex through 4 RRR.

Within G2 subgroups, few individuals belonged to the same family (n=47 for men and 73 for women); thus, 1 individual per family was randomly selected to avoid effects of genetic lineage and clustering. Since a single random selection could not accurately reflect the entire group, 1000 samples were generated by randomly drawing 1 individual from each family (250 of 297 G2 men, and 272 of 345 G2 women), and we performed RRR analysis for each sample. Hierarchical agglomerative clustering using Ward's method with the Euclidean distance as the metric was then performed by taking 6×1000 factors for the individuals. The analyses were performed in G2 men and women separately. We identified the “optimal” number of clusters as suggested by the dendrogram; 6 distinct clusters were identified for men, and 7 were deemed optimal for women. For men, the first cluster comprised 94.4% of factor 1, and the second cluster comprised 97.7% of factor 2; for women, the first and second clusters comprised all of factors 1 and 2, respectively. For each food group, a mean factor loading was calculated from the factors of each cluster and used to calculate the scores for each DP.

The DP scores were calculated at the individual level by summing the observed standardized food intakes per food group weighted according to the factor loadings. We only retained the first 2 factors on the basis of both the variation in the intermediate markers that they explained and their interpretability.

The resulting DPs were qualitatively compared among each of the 4 subgroups. Correlations between sex and then generation groups were tested using Spearman correlations.

We also performed multivariable linear regression analyses stratified by generation and sex to evaluate associations between RRR DPs and subclinical cardiovascular damage; that is, cfPWV, cIMT, and LV mass for each group. The first model was adjusted for age, and the second model was further adjusted for smoking status, education level, energy expenditure, energy intake, any lipid‐lowering drugs, and any antihypertensive or antidiabetic drugs.

Since some of the siblings could be from the same family for G2, we performed sensitivity analyses. Mixed models with a random effect of family were analyzed to investigate the association between DPs and each outcome.

RRR and linear regression analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute). Hierarchical agglomerative clustering was conducted using R software (version 3.5.1).

Results

Characteristics of the Population

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the studied population according to generation and sex. The median (interquartile range) ages were 60.8 (58.2–63.9) and 58.8 (56.3–62.6) years for G1 men and women, respectively, and 33.6 (30.6–37.4) and 33.3 (30.2–36.7) years for G2. G1 participants were less likely to smoke but more likely to have a low education level and higher BMI compared with G2 participants. G1 participants had higher prevalence rates of MetS, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. G1 participants had higher cIMT and cfPWV. LV mass, cIMT, cfPWV, and energy intake were higher in men than women in both generations. G1 participants had higher International Physical Activity Questionnaire–evaluated energy expenditure per week than G2 when compared by sex.

Table 1.

Description of the Studied Population by Generation and Sex

| Generation 1 | Generation 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| N | 434 | 451 | 297 | 345 |

| Age, y | 60.8 (58.2–63.9) | 58.8 (56.3–62.6) | 33.6 (30.6–37.4) | 33.3 (30.2–36.7) |

| Smokers, n (%) | 59 (14) | 41 (9) | 105 (35) | 114 (33) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 289 (67) | 325 (72) | 104 (35) | 85 (25) |

| Intermediate | 90 (21) | 96 (21) | 89 (30) | 112 (32) |

| High | 55 (13) | 30 (7) | 104 (35) | 148 (43) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.9 (24.6–29.7) | 25.2 (22.6–28.8) | 24.5 (22.5–27.2) | 22.6 (20.7–25.5) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 98.4±11.7 | 87.0±12.3 | 89.9±10.4 | 80.2±12 |

| Energy intake, kcal/d | 2539.3 (2044.3–3055.2) | 1972.4 (1558.3–2491) | 2583.7 (2101.7–3159.5) | 1935.9 (1523.2–2540.2) |

| Energy expenditure (MET‐min/week) | 2818.6 (1248–7098) | 1920 (846–3708) | 1920 (741–5406) | 1307.4 (540–2796) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 159 (37) | 107 (24) | 22 (7) | 20 (6) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 45 (10) | 20 (4) | 1 (0) | 7 (2) |

| Fasting glucose, g/L | 0.94 (0.9–1) | 0.89 (0.8–1) | 0.87 (0.8–0.9) | 0.82 (0.8–0.9) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 5.7 (5.5–5.9) | 5.7 (5.5–5.9) | 5.4 (5.2–5.6) | 5.4 (5.2–5.5) |

| Use of antidiabetic drugs, n (%) | 36 (8) | 14 (3) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Elevated triglycerides, n (%) | 186 (43) | 135 (30) | 47 (19) | 21 (8) |

| Triglycerides | 1.05 (0.8–1.5) | 0.96 (0.7–1.3) | 0.86 (0.6–1.3) | 0.74 (0.6–1) |

| HDL‐C, g/L | 0.54 (0.5–0.6) | 0.64 (0.6–0.8) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.59 (0.5–0.7) |

| LDL‐C, g/L | 1.37 (1.1–1.6) | 1.46 (1.2–1.7) | 1.23 (1–1.5) | 1.19 (1–1.4) |

| Use of lipid‐lowering drugs, n (%) | 125 (29) | 86 (19) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 260 (62) | 202 (46) | 74 (28) | 51 (16) |

| Office SBP, mm Hg | 133.5±15.2 | 126.1±16.4 | 126.5±11.2 | 114.5±10.1 |

| Office DBP, mm Hg | 77.1±8.9 | 71.9±8.6 | 72.2±7.5 | 67.8±7.7 |

| 24 h‐SBP, mm Hg | 124.4±9.9 | 118.6±10.7 | 121.8±7.4 | 115.1±7.7 |

| 24 h‐DBP, mm Hg | 77.3±7.1 | 72.9±7.4 | 74.6±5.7 | 72.2±6.4 |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 145 (33) | 123 (27) | 9 (3) | 10 (3) |

| Intima‐media thickness, μm | 707.2 (619.8–788.0) | 667.8 (598.0–740.0) | 530.0 (475.0–597.8) | 508.0 (467.0–559.8) |

| Left ventricular mass, g/height2.7 | 36.7 (31.9–43.6) | 33.4 (28.7–41.1) | 31.6 (27.2–36.5) | 27.2 (23.1–31.9) |

| Pulse‐wave velocity, m/s | 9.3 (8.4–10.6) | 8.5 (7.7–9.5) | 7.6 (7.1–8.3) | 7.2 (6.7–7.9) |

The results for continuous variable are expressed as mean±SD or median (Q1‐Q3) as appropriate. Hypertension is defined as elevated blood pressure (130/80) and/or declared hypertension and/or use of at least 1 antihypertensive drug; diabetes mellitus is defined by high fasting glucose (>1.26 g/L) and/or declared diabetes mellitus and/or use of at least 1 antidiabetic drug. All the differences between subgroups were significant (P<0.0001). DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL‐C, plasma high‐density cholesterol; LDL‐C, plasma low‐density cholesterol; MET, metabolic equivalent task; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Dietary Patterns and Food Groups

In G1 men, the first DP (“meat, fat, and eggs”) was characterized by high intakes of meat, margarine, low‐fat spreads, processed meat, and eggs, and low intakes of spreads, cereals, and sweets (Table 2). This DP explained 14.9%, 10.9%, 4.6%, 7.3%, 0.3%, and 0.1% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 6.4% of the total variation in all 6 metabolic markers. The second DP (“alcohol”) was characterized by high intakes of alcoholic beverages and wine, and low intakes of fruity desserts, vegetables, legumes, eggs, soups, yogurt, and other types of fermented milk, water, and pastries. This DP explained 15.0%, 11.6%, 4.7%, 8.3%, 6.5%, and 8.9% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 2.8% of the total variation.

Table 2.

Reduced‐Rank Regression Factor Loadings for the Dietary Patterns and Explained Variation by Generation and Sex in the STANISLAS Cohort

| Generation 1 | Generation 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | First | Second | |

| Vegetables | −0.147 | −0.269a | 0.051 | 0.174 | 0.120 | −0.106 | −0.163 | −0.017 |

| Soups | 0.162 | −0.227a | −0.089 | −0.211a | −0.081 | 0.322a | −0.210a | 0.036 |

| Fruits | 0.001 | −0.039 | 0.027 | 0.048 | −0.083 | 0.038 | −0.083 | −0.009 |

| Potatoes | 0.097 | −0.089 | 0.141 | −0.019 | 0.059 | −0.112 | 0.177 | −0.106 |

| Other starchy foods | 0.081 | 0.083 | −0.013 | −0.023 | −0.027 | −0.149 | 0.210a | 0.076 |

| White bread and toasts | 0.040 | 0.025 | 0.071 | −0.162 | 0.057 | 0.095 | 0.223a | −0.329a |

| Cereals | −0.301a | −0.006 | −0.114 | −0.032 | −0.127 | −0.019 | −0.109 | −0.115 |

| High‐fiber bread | −0.155 | 0.143 | −0.060 | 0.216a | −0.165 | 0.192 | −0.165 | −0.050 |

| Milk | 0.018 | −0.033 | 0.239a | 0.039 | −0.178 | 0.047 | −0.163 | −0.116 |

| Yogurts and fermented milk | −0.001 | −0.211a | 0.260a | −0.198 | −0.189 | 0.292a | 0.198 | −0.306a |

| Fat cheeses | 0.015 | 0.005 | −0.042 | 0.082 | 0.109 | −0.122 | −0.068 | 0.094 |

| Light cheeses | 0.070 | −0.125 | 0.186 | −0.085 | 0.053 | −0.022 | 0.065 | −0.117 |

| Meat | 0.405a | 0.032 | 0.242a | −0.091 | 0.168 | −0.152 | 0.217a | −0.122 |

| Fatty fish | −0.157 | −0.122 | 0.060 | −0.012 | −0.057 | 0.060 | −0.090 | 0.079 |

| Lean fish | −0.024 | 0.040 | 0.204a | 0.332a | 0.113 | 0.026 | −0.057 | 0.142 |

| Eggs | 0.228a | −0.229a | 0.111 | 0.048 | −0.021 | 0.019 | −0.058 | −0.289a |

| Legumes | −0.081 | −0.246a | 0.071 | 0.229a | −0.023 | 0.043 | 0.050 | 0.054 |

| Oleaginous fruit | 0.033 | −0.007 | −0.116 | 0.103 | −0.099 | −0.047 | 0.013 | −0.172 |

| Olive and omega‐3 oil | −0.156 | −0.020 | −0.066 | 0.380a | 0.321a | −0.040 | −0.241a | 0.022 |

| Omega‐6 oil | −0.030 | 0.075 | 0.189 | 0.072 | 0.190 | 0.327a | −0.027 | −0.089 |

| Fresh cream | 0.072 | −0.010 | 0.041 | −0.005 | 0.173 | 0.003 | 0.021 | −0.203a |

| Margarine and light fats | 0.289a | −0.087 | 0.086 | −0.248a | 0.108 | 0.217a | 0.203a | 0.039 |

| Fats rich in saturated fatty acid | −0.181 | 0.133 | 0.035 | 0.190 | 0.089 | 0.040 | −0.071 | −0.120 |

| Water | −0.056 | −0.217a | 0.074 | −0.105 | 0.219a | −0.022 | 0.119 | 0.132 |

| Alcoholic beverages | −0.109 | 0.385a | 0.020 | 0.179 | 0.316a | 0.148 | −0.248a | 0.133 |

| Wine | −0.080 | 0.332a | 0.050 | 0.074 | 0.202a | 0.132 | −0.152 | 0.142 |

| Juice | −0.087 | −0.145 | −0.025 | 0.001 | −0.078 | 0.021 | −0.072 | −0.230a |

| Sodas | 0.133 | −0.092 | 0.141 | 0.126 | 0.058 | −0.169 | 0.214a | −0.020 |

| Tea | −0.026 | −0.044 | −0.086 | 0.171 | 0.043 | 0.013 | 0.120 | −0.053 |

| Processed meat | 0.276a | 0.045 | 0.275a | −0.112 | 0.059 | 0.254a | 0.139 | −0.114 |

| Fast food | 0.091 | 0.123 | 0.111 | 0.161 | 0.324a | 0.172 | 0.019 | −0.056 |

| Cooked dishes | 0.179 | −0.005 | 0.325a | −0.070 | 0.092 | 0.084 | 0.102 | 0.155 |

| Sugar | −0.087 | 0.010 | −0.028 | −0.182 | 0.026 | −0.199 | 0.114 | 0.059 |

| Sweets | −0.228a | −0.103 | 0.137 | 0.182 | −0.037 | 0.060 | −0.142 | 0.014 |

| Spreads | −0.400a | −0.099 | −0.226a | 0.228a | −0.301a | 0.093 | −0.341a | −0.250a |

| Crackers | 0.139 | −0.097 | 0.062 | 0.136 | 0.097 | 0.033 | 0.020 | −0.009 |

| Fried foods | −0.001 | −0.021 | 0.376a | −0.014 | 0.131 | −0.133 | 0.194 | −0.072 |

| Pastries | −0.066 | −0.241a | 0.016 | 0.032 | −0.222a | 0.214a | −0.154 | −0.260 |

| Fruity desserts | −0.073 | −0.377a | 0.076 | 0.189 | −0.008 | 0.137 | −0.071 | 0.282a |

| Dairy desserts | −0.064 | −0.171 | 0.169 | 0.101 | −0.048 | 0.049 | 0.162 | −0.184 |

| Sauces | 0.047 | 0.000 | 0.348a | 0.203a | 0.077 | −0.149 | 0.124 | 0.023 |

| Explained variation in food groups | 2.9 | 3.3 | 4 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Explained variation in all six components of metabolic syndrome | 6.4 | 2.8 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 4.2 |

Factor loading >0.20 in absolute value.

In G1 women, the first DP (“fried, processed, and dairy products”) was characterized by high intakes of fried foods, sauces, processed meat, yogurt and other types of fermented milk; other types of meat, milk and lean fish; and low intakes of spreads. This DP explained 11.2%, 8.6%, 2.7%, 3.1%, 10.2, and 7.8% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 7.2% of the total variation in all 6 metabolic markers. The second DP (“fiber and w3 oil”) was characterized by high intakes of olive and omega‐3–rich oils, lean fish, legumes, spreads, high‐fiber bread, and sauces, and low intakes of soups, margarine, and light fat. This DP explained 13.5%, 11.2%, 3.8%, 5.3%, 13.1, and 17.4% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 3.5% of the total variation.

In G2 men, the first DP (“fast food and alcohol”) was characterized by high intakes of fast food, olive and omega‐3–rich oils, water, and alcoholic beverages and, wine, and low intakes of pastries and spreads. This DP explained 9.3%, 0.6%, 12.1%, 4.4%, 4.3%, and 6.9% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 6.3% of the total variation in all 6 metabolic markers. The second DP (“diversified”) was characterized by high intakes of omega‐6–rich oil, soups, yogurts and other types of fermented milk, processed meat, margarine, light fat, and pastries. This DP explained 10.3%, 3.1%, 13.1%, 17.0%, 9.3%, and 13.1% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 4.7% of the total variation.

In G2 women, the first DP (“meat, starch, sodas, and fat”) was characterized by high intakes of white bread and toast, meat, sodas, starchy foods other than potatoes, margarine, and light fat, and low intakes of spreads, soups, alcoholic beverages, and olive and omega‐3–rich oils. This DP explained 16.3%, 0.6%, 7.7%, 12.8%, 7.0%, and 4.8% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 8.2% of the total variation in all 6 metabolic markers. The second DP (“fruity desserts”) was characterized by high intakes of fruity desserts and low intakes of white bread and toast, yogurt and other types of fermented milk, eggs, pastries, spreads, juice, and fresh cream. This DP explained 16.7%, 1.8%, 8.7%, 20.3%, 13.1%, and 13.7% of the variations in WC, glucose, triglycerides, HDL‐C, SBP, and DBP, respectively, and 4.2% of the total variation.

It is interesting to stress that we found only unhealthy patterns in both generations of men, whereas 2 healthy patterns were identified in G1 (fiber and w3 oil) and G2 (fruity desserts) women.

Correlation Between Generations and Sexes

Differences were observed between the DPs identified by sex among the same generations. Within G1, the “meat and eggs” DP in men was moderately positively correlated with the “fried, processed, and dairy products” DP in women (r=0.55, P<0.0001), and negatively correlated with the “fiber and w3 oil” DP in women (r=−0.39, P<0.0001). Also, the “alcohol” DP in G1 men was negatively correlated with the “fried, processed, and dairy products” DP (r=−0.20, P<0.001) and marginally correlated with the “fiber and w3 oil” DP (r=−0.04, P=0.09) in G1 women.

Within G2, the “fast food and alcohol” DP in men was weakly correlated with the “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DP (r=0.25, P<0.0001) and the “fruity desserts” DP (r=0.10, P<0.0001) in women. The “diversified” DP in G2 men was negatively correlated with the “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DP (r=−0.32, P<0.0001) and “fruity desserts” DP (r=−0.21, P<0.0001) in women.

Differences were also observed between the DPs identified according to generation in the same sex. The “alcohol” DP in G1 men and “fast food and alcohol” in G2 men were qualitatively similar in terms of alcoholic beverages and wine, but differed in terms of other food groups, and were moderately correlated (r=0.34, P<0.0001). The “meat and eggs” DP in G1 men was moderately correlated with the “fast food and alcohol” DP (r=0.40, P<0.0001) and weakly correlated with the “diversified” DP (r=−0.09, P=0.0005) in G2 men.

The “fried, processed, and dairy products” DP in G1 women was positively correlated with the “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DP (r=0.56, P<0.0001) and negatively with the “fruity desserts” DP (r=−0.36, P<0.0001) in G2 women. The “fiber and w3 oil” DP in G1 women was negatively correlated with the “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DP (r=−0.43, P<0.0001) but not correlated with the “fruity desserts” DP (r=−0.02, P=0.35) in G2 women.

Association Between Dietary Patterns and Subclinical Cardiovascular Damage

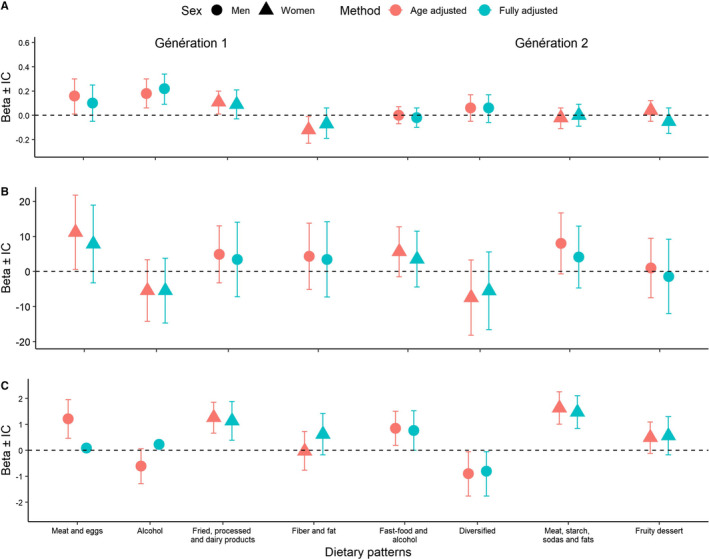

In women, the “fried, processed, and dairy products” DP (G1) and the “meat, starch, and fat” DP (G2) were associated with higher LV mass. In G1 men, the “alcohol” DP was significantly associated with a higher cfPWV (Figure). The “meat and eggs” DP was significantly associated with a higher cIMT in the first model adjusted for age, but not in the fully adjusted model. The DPs “alcohol” and “fast food and alcohol” in G1 and G2 men, respectively, were significantly and positively associated with LV mass. The other DPs were not associated with any of the outcomes.

Figure 1.

Association of dietary patterns with pulse wave velocity (A), carotid intima‐media thickness (B), left ventricular mass (C) (β and 95% CI). For the fully adjusted model: multivariable linear regression analyses are also adjusted for smoking status (yes/no), educational level (low, intermediate, high), energy expenditure, energy intake, any lipid‐lowering drugs (yes/no), any antihypertensive drugs (yes/no) or antidiabetics (yes/no).

Given that multiple individuals in G2 could be siblings from the same family, we performed sensitivity analyses with a random effect of family (Table 3). The β values were lower but remained within the same range, and we observed the same association as in previous analyses between the “meat, starch, and fat” DP in G2 women and LV mass.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses Assessing the Associations Between Dietary Pattern Scores and Subclinical Cardiovascular Damage With a Random Effect on the Family for Generation 2 Only

| Generation 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||

| Pattern 1 | Pattern 2 | Pattern 1 | Pattern 2 | |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| cfPWV | ||||

| M1 | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.14) | 0.007 (−0.09 to 0.10) | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.06) |

| M2 | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.10 to 0.14) | 0.0005 (−0.09 to 0.09) | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.06) |

| cIMT | ||||

| M1 | 4.03 (−4.57 to 12.64) | −6.65 (−18.59 to 5.28) | 6.90 (−2.27 to 16.06) | −0.66 (−11.68 to 10.35) |

| M2 | 3.83 (−4.54 to 12.19) | −5.70 (−17.28 to 5.88) | 4.43 (−4.66 to 13.52) | −1.32 (−12.22 to 9.57) |

| LV mass | ||||

| M1 | 0.65 (0.13 to 1.17) | −1.12 (−1.90 to −0.33) | 1.89 (1.20 to 2.58) | 0.47 (−0.21 to 1.14) |

| M2 | 0.57 (−0.03 to 1.17) | −0.97 (−1.81 to 0.12) | 1.74 (1.02 to 2.46) | 0.47 (−0.40 to 1.34) |

Data are β‐coefficients and 95% CI. M1: linear mixed model adjusted for age. M2: multivariable linear regression analyses also adjusted for smoking status (yes/no), educational level (low, intermediate, high), energy expenditure, energy intake, any lipid‐lowering drugs (yes/no), any antihypertensive drugs (yes/no) or antidiabetics (yes/no). The models were performed with a random effect on the family. cfPWV indicates carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity; cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness; LV, left ventricular.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide original insights into DPs that maximally explain the variation in MetS components. The findings highlight for the first time that DPs differ qualitatively between generations and sex and exhibit different associations with specific subclinical cardiovascular damage outcomes in a population‐based cohort that includes initially healthy participants.

Some unhealthy and distinct DPs were found to be associated with LV mass in both generation and sex and cfPWV in G1 men only. While some studies have examined DPs separately in men and women and in different generations,25, 26, 27 to our knowledge no previous study has focused on dietary intake simultaneously according to both generation and sex. Despite few moderate correlations being found between DPs derived according to generation and sex, qualitative differences between similar DPs were observed. We found that the DPs for men of both generations were mostly characterized by alcohol consumption, while fast‐food intake was common only in G2 men. We found unhealthy DPs that were correlated in women of both generations, although their main common food group was “processed meat.” We also identified one healthy DP in each generation of women that were qualitatively different and not correlated: “fruity desserts” in G2 women and “fiber and w3 oil” in G1 women. These findings indicate the need to perform analyses according to generations.

The role of RRR is not to describe real‐world DPs but to find out what variation in diet is important for the development of specific health issues. The “fried, processed, and dairy products” DP in G1 women and the “meat, starch, sodas, and fat” DP in G2 women; and also the “alcohol” DP in G1 men and “fast food and alcohol” in G2 men were positively and significantly associated with LV mass. Another study derived DPs using the RRR method with MetS as the intermediate variables and found a DP characterized by several foods including those with high glycemic indices, high‐fat meats, cheeses, and processed foods, and negatively correlated with intakes of vegetables, soy, fruit, green and black tea, low‐fat dairy desserts, seeds, nuts, and fish.41 That DP was positively associated with LV function, but it was not derived according to sex. It is interesting to note that in our study the identified DPs also differed between generations. LV mass was associated with DPs characterized by unhealthy food in women in both generations—whereas in men of both generations the DPs were mostly characterized by alcohol. Although the results concerning the associations between alcohol intake and LV mass are still debated, our results seemed to support the studies showing a positive relation between drinking and LV mass.42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Nonetheless, these studies usually focused in men or did not distinguish sex. In the Framingham study, an association between alcohol intake and LV mass was also found in men and not in women.47 The metabolism of alcohol is different according to sex.48 Although women seem to have a higher vulnerability to alcohol, in the present study none of the DPs of the women is characterized by alcohol intake. It is also interesting to note that women had a lower energy expenditure compared with men of the same generation, with this being lowest in G2 women. Since high physical activity has been found to be associated with reduced LV hypertrophy in obese and hypertensive patients,49 it is possible that a low energy expenditure contributed to the association between DP characterized by unhealthy food and LV mass in our population.

cfPWV was positively associated with the “alcohol” DP identified in G1 men. This result is consistent with O'Neill et al9 finding an association between alcohol consumption and cfPWV, and Kesse‐Guyot et al15 using principal‐components analysis to identify a DP characterized by “meat and alcohol” that is associated with an increased cfPWV. However, our “fast food and alcohol” DP identified in G2 men was not associated with cfPWV. A possible explanation is that the effect of alcohol on cardiovascular organ damage might not have been detectable yet in G1 and that this association would have been identified only if data from a longer follow‐up were available.

The results for the DP associations with outcomes differed between sex and generation, which could be due to the cardiovascular risks and evolution of cardiovascular damage differing between men and women,50, 51 and hence that the determinants of cardiovascular risks also differ by sex. The impact of diet on cardiovascular damage may differ between women and men, in relation to their specific cardiometabolic profiles.

It is interesting to note that that only healthy DPs identified in our cohort were the “fruity desserts” DP in G2 women and the “fiber and w3 oil” DP in G1 women. Two other studies used RRR with cardiovascular risk factors as intermediate variables and also did not observe any healthy DPs. Lamichhane et al52 observed a DP that was correlated positively with an intake of eggs, coffee, tea, sodas, potatoes, and meat, and negatively with an intake of desserts and low‐fat dairy. Liu et al41 observed a DP that was correlated positively with a high glycemic index, high‐fat meats, cheeses, and processed foods, and negatively with low intakes of vegetables, soy, fruit, green and black tea, low‐fat dairy desserts, seeds, nuts, and fish. A review suggested an association between cIMT and Mediterranean‐diet score.18 No association was found between cIMT and the identified DP in the present study, which could be due to the dearth of healthy DP. Kesse‐Guyot et al also did not find any association between a “meat and alcohol” DP and cIMT.15 Using an RRR‐derived DP with inflammation as intermediate variables, comprising C‐reactive protein, fibrinogen, interleukin‐6, and homocysteine, Nettleton et al identified a “high in total and saturated fat and low in fiber and micronutrients” DP that was associated with cIMT. These findings together link inflammation markers to cardiovascular damage, indicating that could be a potentially relevant mediator for refining RRR DP when studying cIMT.53

Strengths and Limitations

The present study had several strengths. First, the analyses were based on a large general and initially healthy population‐based cohort with the availability of complete information on diet, MetS components, and extensive cardiovascular phenotyping. Second, the cohort was a family cohort with 2 generations, allowing us to determine DPs according to subgroups of generation and sex. Third, we used the RRR method to test the hypothesis of there being a pathway between diet, MetS, and subclinical cardiovascular damage.

However, some limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. First, the results are based on cross‐sectional data and hence the observational design meant that causality could not be implied. Second, the food intake of individual participants might have changed throughout the life course because of age or a disease diagnosis. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the pathway involving diet, MetS, and subclinical cardiovascular damage, especially in subgroups of generation and sex. Third, whereas these original findings need to be confirmed by other studies, it is noteworthy that previous research has demonstrated the generalizability and robustness of the RRR method in calculating DP among populations.54

In conclusion, to our knowledge this study is the first to highlight that DP that explain the maximum variation in MetS components differ with the generation and sex, and show different associations with subclinical cardiovascular damage according to generation and sex. Our results suggest that dietary recommendations should be tailored according to age and sex groups. Further analyses are required to determine the role of the evolution of dietary habits across the life course and subsequently to determine if changing DPs can reduce cardiovascular damage.

Sources of Funding

The fourth examination of the STANISLAS study was sponsored by the Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of Nancy (CHRU) and the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Inter‐régional 2013), by the Contrat de Plan Etat‐ Lorraine and “Fonds Européen de Développement Régional” (FEDER Lorraine), and by a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the second “Investissements d'Avenir” program FIGHT‐HF (reference: ANR‐15‐RHU‐0004) and by the French “Projet investissement d'avenir” (PIA) project “Lorraine Université d'Excellence” (reference ANR‐15‐IDEX‐04‐LUE). It is also supported by the Sixth European Union—Framework program (EU‐FP) Network of Excellence Ingenious HyperCare (#LSHM‐CT‐2006–037093), the Seventh EU‐FP MEDIA (Européen “Cooperation”—Theme “Health”/FP7‐HEALTH‐2010‐single‐stage #261409), HOMAGE (grant agreement NO. Heart “Omics” in Ageing, 7th Framework Program grant #305507), FOCUS‐MR (reference: ANR‐15‐CE14‐0032‐01), and FIBRO‐TARGETS (FP7#602904) projects, and by ERA‐CVD EXPERT (reference: ANR‐16‐ECVD‐0002‐02). The study was supported by the F‐Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (F‐CRIN) Cardiovascular and Renal Clinical Trialists (INI‐CRCT) and French Obesity Research Centre of Excellence (FORCE) network. This work was supported by the French “Fondation de Recherche sur l'Hypertension Artérielle.”

Disclosures

Pr Rossignol received personal fees (consulting) for Idorsia and G3P, honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, CVRx, Fresenius, Grunenthal, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Servier, Stealth Peptides, Ablative Solutions, Corvidia, Relypsa and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma, outside the submitted work, and he is the cofounder of CardioRenal. Pr Girerd received honoraria from Novartis, Bohringer, and Servier. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. Compositions of the Selected 41 Food Groups

Figure S1. Study flowchart.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply thank the Staff of the Clinical Investigation Center and other personnel involved in the STANISLAS cohort management: Biostatisticians: Fay R, Lamiral Z, Machu JL. Computer scientists: Boucenna N, Gallina‐Müller C, Maclot PL, Sas T. Co‐investigators: Chau K, Di Patrizio P, Dobre D, Gonthier D, Huttin O, Malingrey L, Mauffrey V, Olivier A, Poyeton T, Steyer E, Watfa G. Data managers: Cimon P, Eby E, Merckle L. Data entry operators: Batsh M, Blanger O, Bottelin C, Haskour N, Jacquet V, Przybylski MC, Saribekyan Y, Thomas H, Vallée M. Echocardiographists, echographists: Ben Sassi M, Cario S, Camara Y, Coiro S, Frikha Z, Kearney‐Schwartz A, Selton‐Suty C, Watfa G. Imaging engineer: Bozec E. Laboratory engineer: Nuée‐Capiaumont J; and technicians: Fruminet J, Kuntz M, Ravey J, Rousseau E, Tachet C. Project manager: Bouali S, Hertz C. Quality engineer: Lepage X. Registered nurses: Giansily M, Poinsignon L, Robin N, Schmartz M, Senn M, Micor‐Patrignani E, Toutlemonde M. Hospital technician: Fleurot MT. Resident doctors: Alvarez‐Vasquez R, Amiot M, Angotti M, Babel E, Balland M, Bannay A, Basselin P, Benoit P, Bercand J, Bouazzi M, Boubel E, Boucherab‐Brik N, Boyer F, Champagne C, Chenna SA, Clochey J, Czolnowski D, Dal‐Pozzolo J, Desse L, Donetti B, Dugelay G, Friang C, Galante M, Garel M, Gellenoncourt A, Guillin A, Hariton ML, Hinsiger M, Haudiquet E, Hubert JM, Hurtaud A, Jabbour J, Jeckel S, Kecha A, Kelche G, Kieffert C, Laurière E, Legay M, Mansuy A, Millet‐ Muresan O, Meyer N, Mourton E, Naudé AL, Pikus AC, Poucher M, Prot M, Quartino A, Saintot M, Schiavi A, Schumman R, Serot M, Sert C, Siboescu R, Terrier‐de‐la‐Chaise S, Thiesse A, Thietry L, Vanesson M, Viellard M. Secretaries: De Amorin E, Villemain C, Ziegler N. Study coordinators: Dauchy E, Laurent S; and all people not listed above who helped to the funding, initiation, accrual, management and analysis of the fourth visit of the STANISLAS cohort. They also thank the CRB Lorrain BB‐0033‐00035 of the Nancy CHRU for management of the biobank. We thank M Pierre Pothier for the editing of the manuscript. Steering committee: Pierre Mutzenhardt, Mehdy Siaghy, Patrick Lacolley, Marie‐Ange Luc, Pierre Yves Marie, Jean Michel Vignaud. Advisory members: Sophie Visvikis Siest, Faiez Zannad. Technical committee: Christiane Branlant, Isabelle Behm‐Ansmant, Jean‐Michel Vignaud, Christophe Philippe, Jacques Magdalou, Faiez Zannad, Patrick Rossignol. Scientific committee: Laurence Tiret, Denis Wahl, Athanase Benetos, Javier Diez, Maurizio Ferrari, Jean Louis Gueant, Georges Dedoussis, François Alla, François Gueyffier, Pierre‐Yves Scarabin, Claire Bonithon Kopp, Xavier Jouven, Jean‐Claude Voegel, Jan Staessen. We also thank all of the Stanislas cohort participants. We thank English Science Editing for revising the English of this manuscript.

Drs Rossignol, Girerd, Boivin, and Zannad designed the fourth visit of the STANISLAS cohort. Drs Nazare, Wagner, Rossignol, and Girerd designed the present research. Food data were checked and corrected by Drs Van den Berghe, Wagner, Nazare, Hoge, and Donneau. Drs Bozec and Girerd supervised the cardiovascular (arterial stiffness and thickness and echocardiography respectively) assessments. Dr Mercklé performed the data management of the data. Drs Wagner, Nazare, Lioret, Rossignol, and Girerd designed the study analyses, which were performed by Drs Wagner and Duarte, and the help of Lamiral. Drs Wagner, Lioret, and Nazare drafted the manuscript. All the authors were involved in the interpretation of the results and the critical review of the manuscript, and approved the manuscript.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e013836 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013836.)

References

- 1. Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta‐analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Widmer RJ, Flammer AJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2015;128:229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Fast food pattern and cardiometabolic disorders: a review of current studies. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;5:231–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adriouch S, Lelong H, Kesse‐Guyot E, Baudry J, Lampuré A, Galan P, Hercberg S, Touvier M, Fezeu LK. Compliance with nutritional and lifestyle recommendations in 13,000 patients with a cardiometabolic disease from the Nutrinet‐Santé study. Nutrients. 2017;9:E546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang X‐Y, Shu L, Si C‐J, Yu X‐L, Liao D, Gao W, Zhang L, Zheng P‐F. Dietary patterns, alcohol consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in adults: a meta‐analysis. Nutrients. 2015;7:6582–6605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all‐cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1318–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tardif JC, Heinonen T, Orloff D, Libby P. Vascular biomarkers and surrogates in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2006;113:2936–2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mancini GBJ. Surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease: structural markers. Circulation. 2004;109:IV22–IV30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Neill D, Britton A, Brunner EJ, Bell S. Twenty‐five‐year alcohol consumption trajectories and their association with arterial aging: a prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005288 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan H‐T, Chan Y‐H, Yiu KH, Li S‐W, Tam S, Lau C‐P, Tse H‐F. Worsened arterial stiffness in high‐risk cardiovascular patients with high habitual carbohydrate intake: a cross‐sectional vascular function study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crichton GE, Elias MF, Dore GA, Abhayaratna WP, Robbins MA. Relations between dairy food intake and arterial stiffness: pulse wave velocity and pulse pressure. Hypertension. 2012;59:1044–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, Li W, Mohan V, Iqbal R, Kumar R, Wentzel‐Viljoen E, Rosengren A, Amma LI, Avezum A, Chifamba J, Diaz R, Khatib R, Lear S, Lopez‐Jaramillo P, Liu X, Gupta R, Mohammadifard N, Gao N, Oguz A, Ramli AS, Seron P, Sun Y, Szuba A, Tsolekile L, Wielgosz A, Yusuf R, and Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390:2050–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zyriax B‐C, Lau K, Klähn T, Boeing H, Völzke H, Windler E. Association between alcohol consumption and carotid intima‐media thickness in a healthy population: data of the STRATEGY study (Stress, Atherosclerosis and ECG Study). Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newby PK, Tucker KL. Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:177–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kesse‐Guyot E, Vergnaud A‐C, Fezeu L, Zureik M, Blacher J, Péneau S, Hercberg S, Galan P, Czernichow S. Associations between dietary patterns and arterial stiffness, carotid artery intima‐media thickness and atherosclerosis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gardener H, Rundek T, Wright CB, Gu Y, Scarmeas N, Homma S, Russo C, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL, Di Tullio MR. A Mediterranean‐style diet and left ventricular mass (from the Northern Manhattan Study). Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:510–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levitan EB, Ahmed A, Arnett DK, Polak JF, Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Heckbert SR, Jacobs DR, Nettleton JA. Mediterranean diet score and left ventricular structure and function: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petersen KS, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. The association between carotid intima media thickness and individual dietary components and patterns. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Laaksonen MML, Juonala M, Viikari J, Pietinen P, Raitakari OT. Long‐term dietary patterns and carotid artery intima media thickness: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Majstorovic A, Pencic B, Backovic S, Ivanovic B, Scepanovic R, Martinov J, Kocijancic V, Celic V. Does the metabolic syndrome impact left‐ventricular mechanics? A two‐dimensional speckle tracking study. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1870–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stehouwer CDA, Henry RMA, Ferreira I. Arterial stiffness in diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: a pathway to cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia. 2008;51:527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aydin M, Bulur S, Alemdar R, Yalçin S, Türker Y, Basar C, Aslantas Y, Yazgan Ö, Albayrak S, Özhan H; Melen Investigators . The impact of metabolic syndrome on carotid intima media thickness. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2295–2301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodríguez‐Monforte M, Sánchez E, Barrio F, Costa B, Flores‐Mateo G. Metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:925–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoffmann K, Schulze MB, Schienkiewitz A, Nöthlings U, Boeing H. Application of a new statistical method to derive dietary patterns in nutritional epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:935–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lioret S, McNaughton SA, Crawford D, Spence AC, Hesketh K, Campbell KJ. Parents’ dietary patterns are significantly correlated: findings from the Melbourne Infant Feeding Activity and Nutrition Trial Program. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bertin M, Touvier M, Dubuisson C, Dufour A, Havard S, Lafay L, Volatier J‐L, Lioret S. Dietary patterns of French adults: associations with demographic, socio‐economic and behavioural factors. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bezerra IN, Bahamonde NMSG, Marchioni DML, Chor D, de Oliveira Cardoso L, Aquino EM, da Conceição Chagas de Almeida M, Del Carmen Bisi Molina M, de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca M, de Matos SMA. Generational differences in dietary pattern among Brazilian adults born between 1934 and 1975: a latent class analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:2929–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jin H, Nicodemus‐Johnson J. Gender and age stratified analyses of nutrient and dietary pattern associations with circulating lipid levels identify novel gender and age‐specific correlations. Nutrients. 2018;10:E1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferreira JP, Girerd N, Bozec E, Mercklé L, Pizard A, Bouali S, Eby E, Leroy C, Machu J‐L, Boivin J‐M, Lamiral Z, Rossignol P, Zannad F. Cohort profile: rationale and design of the fourth visit of the STANISLAS cohort: a familial longitudinal population‐based cohort from the Nancy region of France. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:395–395j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sauvageot N, Alkerwi A, Adelin A, Guillaume M. Validation of the food frequency questionnaire used to assess the association between dietary habits and cardiovascular risk factors in the NESCAV study. Nutr J. 2013;12:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chau K, Girerd N, Bozec E, Ferreira JP, Duarte K, Nazare J‐A, Laville M, Benetos A, Zannad F, Boivin J‐M, Rossignol P. Association between abdominal adiposity and 20‐year subsequent aortic stiffness in an initially healthy population‐based cohort. J Hypertens. 2018;36:2077–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bortel LMV, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank J k, Backer TD, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace‐Raso FU, Protogerou AD, Schillaci G, Segers P, Vermeersch S, Weber T. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30:445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coiro S, Huttin O, Bozec E, Selton‐Suty C, Lamiral Z, Carluccio E, Trinh A, Fraser AG, Ambrosio G, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Girerd N. Reproducibility of echocardiographic assessment of 2D‐derived longitudinal strain parameters in a population‐based study (the STANISLAS Cohort study). Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33:1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frikha Z, Girerd N, Huttin O, Courand PY, Bozec E, Olivier A, Lamiral Z, Zannad F, Rossignol P. Reproducibility in echocardiographic assessment of diastolic function in a population based study (the STANISLAS Cohort study). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cuspidi C, Giudici V, Negri F, Meani S, Sala C, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. Improving cardiovascular risk stratification in essential hypertensive patients by indexing left ventricular mass to height(2.7). J Hypertens. 2009;27:2465–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Simone G, Devereux RB, Daniels SR, Koren MJ, Meyer RA, Laragh JH. Effect of growth on variability of left ventricular mass: assessment of allometric signals in adults and children and their capacity to predict cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferreira JP, Girerd N, Bozec E, Machu JL, Boivin J‐M, London GM, Zannad F, Rossignol P. Intima‐media thickness is linearly and continuously associated with systolic blood pressure in a population‐based cohort (STANISLAS Cohort study). J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003529 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lopez‐Sublet M, Girerd N, Bozec E, Machu J‐L, Ferreira JP, Zannad F, Mourad J‐J, Rossignol P. Nondipping pattern and cardiovascular and renal damage in a population‐based study (the Stanislas Cohort study). Am J Hypertens. 2019;32:620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Expert Panel on Detection E . Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scuteri A, Cunha PG, Cucca F, Cockcroft J, Raso FUM, Muiesan ML, Ryliškyt≐ L, Rietzschel E, Strait J, Vlachopoulos C, Laurent S, Nilsson PM, Lakatta EG. Arterial stiffness and influences of the metabolic syndrome: a cross‐countries study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu L, Nettleton JA, Bertoni AG, Bluemke DA, Lima JA, Szklo M. Dietary pattern, the metabolic syndrome, and left ventricular mass and systolic function: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:362–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang Y, Zhang N, Huang W, Feng R, Feng P, Gu J, Liu G, Lei H. The relationship of alcohol consumption with left ventricular mass in people 35 years old or older in rural areas of Western China. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11:220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Askanas A, Udoshi M, Sadjadi SA. The heart in chronic alcoholism: a noninvasive study. Am Heart J. 1980;99:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lazarević AM, Nakatani S, Nešković AN, Marinković J, Yasumura Y, Stojičić D, Miyatake K, Bojić M, Popović AD. Early changes in left ventricular function in chronic asymptomatic alcoholics: relation to the duration of heavy drinking. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park SK, Moon K, Ryoo J‐H, Oh C‐M, Choi J‐M, Kang JG, Chung JY, Young Jung J. The association between alcohol consumption and left ventricular diastolic function and geometry change in general Korean population. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Long MJ, Jiang CQ, Lam TH, Lin JM, Chan YH, Zhang WS, Jin YL, Liu B, Thomas GN, Cheng KK. Alcohol consumption and electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and mediation by elevated blood pressure in older Chinese men: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Alcohol. 2013;47:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Manolio TA, Levy D, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, Kannel WB. Relation of alcohol intake to left ventricular mass: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, Terpin M, Baraona E, Lieber CS. High blood alcohol levels in women. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kamimura D, Loprinzi PD, Wang W, Suzuki T, Butler KR, Mosley TH, Hall ME. Physical activity is associated with reduced left ventricular mass in obese and hypertensive African Americans. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shub C, Klein AL, Zachariah PK, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. Determination of left ventricular mass by echocardiography in a normal population: effect of age and sex in addition to body size. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Humphries K, Izadnegadar M, Sedlak T, Saw J, Johnston N, Schenck‐Gustafsson K, Shah R, Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Grewal J, Vaccarino V, Wei J, Bairey Merz C. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease—impact on care and outcomes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017;46:46–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lamichhane AP, Liese AD, Urbina EM, Crandell JL, Jaacks LM, Dabelea D, Black MH, Merchant AT, Mayer‐Davis EJ. Associations of dietary intake patterns identified using reduced rank regression with markers of arterial stiffness among youth with type 1 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:1327–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nettleton JA, Steffen LM, Schulze MB, Jenny NS, Barr RG, Bertoni AG, Jacobs DR. Associations between markers of subclinical atherosclerosis and dietary patterns derived by principal components analysis and reduced rank regression in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1615–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huybrechts I, Lioret S, Mouratidou T, Gunter MJ, Manios Y, Kersting M, Gottrand F, Kafatos A, De Henauw S, Cuenca‐García M, Widhalm K, Gonzales‐Gross M, Molnar D, Moreno LA, McNaughton SA. Using reduced rank regression methods to identify dietary patterns associated with obesity: a cross‐country study among European and Australian adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2017;117:295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Compositions of the Selected 41 Food Groups

Figure S1. Study flowchart.