Abstract

Theory-guided nursing practice is foundational in providing the framework for the development of excellent nursing care. There is a need for effective care programs for nurses, whereby they are adequately supported within their workplace infrastructures as a professional group whose work is essential to the provision of healthcare worldwide. Likewise, there is a need for care programs for nurses to be theory-guided. In the current global pandemic climate, the well-being of nurses continues to become compromised evidenced by increasing moral distress, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Theory-based supportive programs are vital to the overall wellbeing, morale, and retention of nurses. The Roy Adaptation Theory may serve as a guide in the development and evaluation of a hospital-based program designed to support the needs of the healthcare team. This discussion will explore the application of the Roy Adaptation Theory-Group Identity Mode to the Tea for the Soul Care Model for nurses.

Highlights

-

•

Theory-guided hospital-based programs for nurses effective in addressing nurse well-being

-

•

Moral distress, compassion fatigue, and burnout are likely to increase with Covid-19.

-

•

Nurses benefit from support by the Spiritual Care Team.

-

•

Facilitating reflective practice and sacred spaces in the work environment are essential in supporting nurse well-being.

The value of theory-guided nursing practice as it relates to patient care is well documented in the literature (Ahtisham & Quennell, 2019). Historically, nursing practice had been predominantly focused on evidence and traditional practice. Theoretical models guiding nurse self-care have followed a similar trajectory. Theoretically guided care programs for nurses may help demonstrate the substantiation and effectiveness of these programs that are urgently needful in light of the current global pandemic and the additional emotional strain being placed on nurse well-being. The purpose of this discussion is to demonstrate how a grand nursing theory serves as a useful and relevant model by which to implement and evaluate a hospital-based care program addressing the well-being of nurses and other healthcare team members.

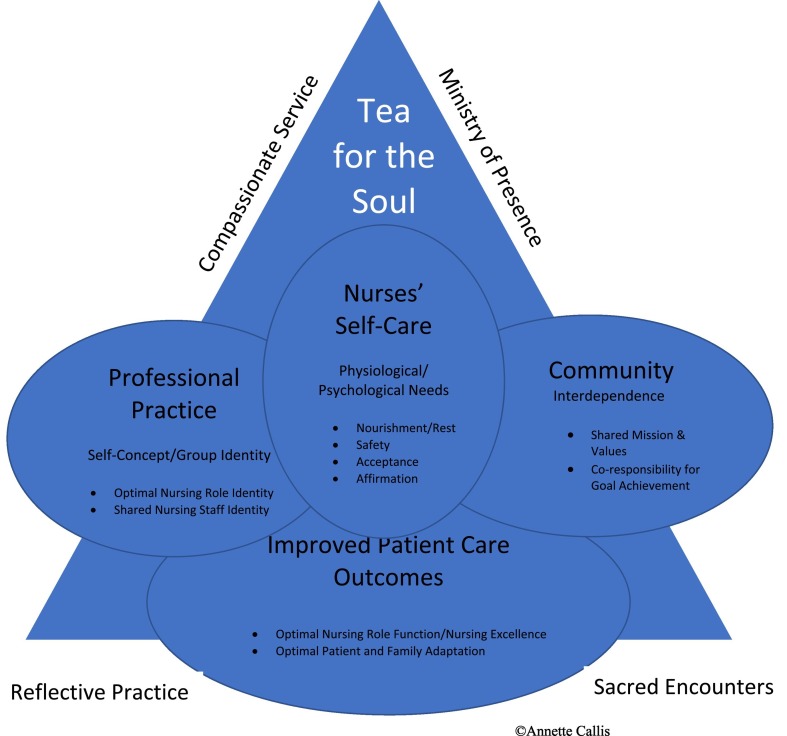

The literature supports a plethora of phenomena that negatively affect nurse well-being such as compassion fatigue, burnout, moral distress, compromised work environments, frequently dealing with patient death, and currently the burdens associated with a global pandemic. Tea for the Soul (TFS) is a hospital-based care program for nurses administrated by chaplains and or social workers. The Roy Adaptation Model is based on a framework that analyzes how an individual or group interacts and responds to stimuli in the environment. TFS counselors are well-positioned within the organization to assist nurses in processing the staggering degree of stimuli they encounter in the present-day complex healthcare environment. Care program facilitators can assist the nurse in mediating adaptive responses to the events they experience in caring for patients and families (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical Framework: Tea for the Soul Program Outcomes (Roy Adaptation Model Application)

1. Phenomena affecting nurse well-being

Compassion fatigue, burnout, and moral distress in nurses cause symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, insomnia, frustration, anger, depression, gastrointestinal upset, and hypertension (McAndrew et al., 2018). It is essential to this discussion to examine the unique burdens of care that nurses experience as a result of the demanding and traumatic work they are called to do.

1.1. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and bereavement

A salient characteristic of compassion fatigue (CF) is its continuous and repeated exposure to stress (Jenkins, 2013). Compassion fatigue is the construct used to describe secondary traumatic stress and burnout. Prior to Figley's (1995) redefinition of compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress, CF was originally coined in the healthcare arena by Joinson (1992), when she noticed that nurses dealing with frequent heartache had lost their “ability to nurture” (p. 116).

Burnout incorporates both physical and emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of patients, negative attitudes, and low feelings of personal and work accomplishments (Hinderer et al., 2014). Stayt (2010) reported, “persistent exposure to death can increase nurses' stress levels and lead to profound grief, which in turn can lead to occupational burnout.” Rushton et al. (2015) utilized six instruments measuring burnout, moral distress and resilience among nurses (N = 140). Moral distress was found to be a significant predictor of burnout, and the association between burnout and resilience was strong. Greater resilience protected nurses from emotional exhaustion. Spiritual well-being was found to reduce emotional exhaustion. Likewise, Peterson et al. (2010) found that nurses expressed what helped them view death as a natural part of life was a religious or spiritual belief.

Multiple studies have shown that aggressive care in cases of futility is the leading cause of moral distress in nurses (Corley, 2002; Elpern et al., 2005; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Schluter et al., 2008). The inappropriate use of life support may prolong patient suffering and their impending death. Nurses need emotional support in processing the increasing mortality and morbidity rates surrounding the present-day global pandemic, as well as needing a system that provides them with support in coming to terms with their own personal grieving related to dying patients.

1.2. Moral distress, job satisfaction, and work environments

Moral distress is frustration in nurses resulting from not being able to carry out an action believed to be morally correct, due to a variety of primarily organizational constraints, and causes nurses to leave critical care and the nursing profession. Browning (Callis) (2013) found that critical care nurses who felt more empowered in the workplace, experienced moral distress less frequently. One might hope interventional studies to empower nurses would decrease moral distress. Although this is a promising direction, a more recent study (Altaker et al., 2018) suggested that nurses with lower perceived empowerment may feel less moral obligation, and therefore less moral distress. There remains a need for interventional studies exploring methods to ameliorate moral distress and enhance job satisfaction and healthy work environments for nurses.

Nurses may be blamed by family or healthcare team members when situations involving a patient death do not result in what is perceived to be a favorable or ethically correct outcome (Yim et al., 2013). According to Tranter et al. (2016) nurses experienced physical, emotional, and relationship changes at home due to stressors carried over from work.

Increased job satisfaction is associated with Healthy Work Environments (HWEs). Much of the literature prior to 2010 focused on the nurse's external environment. Studies on HWEs focused on managers being responsible for developing staff communication skills. Kupperschmidt et al. (2010) developed essentials for nurses to take responsibility for their self-awareness, feelings of grief, need for reflection, and ability to hear and speak the truth. More recent studies (Ross, et al., 2020) are illuminating the need for nurses to engage in a personal self-examination to become more self-aware in the workplace. Perhaps program models conjoining a shared responsibility for nurse well-being between the employer and the nurse can best address nurse needs.

2. Care models for nurses

The need for care models for nurses has emerged from longstanding evidence of phenomena negatively affecting the well-being of nurses. These distresses affect nurse retention and cause nurses to leave the nursing profession. It is imperative that organizational chief nursing officers and administrators address the unique needs of their nursing staff, by providing programs to promote the emotional well-being of nurses. The current 2020 COVID-19 crisis has precipitated the National Well-Being Initiative for Nurses, a partnership with the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, American Nurses Association, American Nurses Foundation, American Psychiatric Nurses Association, and Emergency Nurses Association. These organizations recognize and are taking action to address the compromised well-being of frontline nurses who are facing unprecedented work conditions, unlike ever before.

Potter et al. (2013) explored a hospital-wide CF resiliency program. This program facilitated professional caregivers in recognizing the physical, mental, and emotional effects of stress and adopted resiliency strategies. This program design was based on the principle that nurses need to excel in self-awareness to promote their own sense of well-being so as to engage and effectively impact the well-being of others. Discussing concerns in groups resulted in greater awareness that colleagues were experiencing similar difficulties. Results showed decreased CF, with statistically significant decreases in burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The authors recommended, “If health care organizations want their staff to take better care of their patients, it is incumbent upon leaders of those organizations to give them the tools to take better care of themselves (p. 332).”

The majority of the literature surrounding care programs for nurses is related to self-care programs (Blackburn et al., 2020). Schwartz Rounds® is a program that has been implemented internationally to enhance hospital staff compassionate caring and psychological well-being (Lown, 2018). Significant improvements were found in burnout and joy at work with the implementation of a mindfulness and compassion-oriented training program for nurses (Orellana-Rios et al., 2017).

The results of a recent systematic review (Fernandez et al., 2020) exploring the experiences of nurses working in the acute care hospital setting during the pandemic confirm the need for nurse care programs. The review concluded there is a significant need for strategies related to nurse self-care and the need for healthcare agencies to actively engage in ongoing support for nurses to ensure that the mental and physical health of nurses is optimally addressed and sustained.

2.1. Tea for the soul

TFS is an anecdotally documented and understudied care model that addresses the bereavement and other emotional needs of nurses. This a unique in-hospital program that provides the healthcare team a venue whereby nurses express and explore their feelings and receive feedback from a trained professional about ways of coping effectively with patient death, and other stressful and traumatic experiences. Nurses receive emotional support, compassion, and gain a greater sense of resilience from the TFS facilitator, a Chaplain, Social Worker or Counselor (Drexler & Cimini, 2017).

TFS was first initiated by Rev. Joseph Oloimooja, Director of Spiritual Care Services, at a Medical Center in Los Angeles, California in 1991. Chaplaincy regularly visited staff on their units, serving hot tea and refreshments, offering nurses support in the face of their challenges and included a reflection (inspirational quotations) as a source of comfort. In the last decade, this program has been adopted in numerous healthcare organizations in the US (Davidson et al., 2016). Standardizing this structured program in the care of nursing staff may be a readily available resource to improve the well-being of nurses and promote healthy work environments.

TFS trained counselors may be well positioned to help meet the bereavement needs of nurses in various areas of practice by assisting them in identifying and articulating their feelings of grief and distress. TFS counselors may also help meet nurses' bereavement needs by offering them spiritual insights as a source of strength and adaptive coping. As previously discussed, studies have shown spiritual well-being was found to reduce emotional exhaustion (Rushton et al., 2015) and spiritual beliefs helped nurses in their view of death (Peterson et al., 2010).

Corley (2002) further developed her theory on moral distress by postulating acts of moral courage can mitigate moral distress. A strategy to enhance the development of moral courage in nurses is creating sacred spaces (Iseminger, 2010; Pijl-Zieber et al., 2008). “A sacred space is a defined physical space that invites contemplation, encourages an attitude of openness, and encourages story telling for the specific purpose of connection, support, and healing” (Edmonson, 2010). Collaborative partnerships between the hospital and the Spiritual Care Team can provide nurses with a space to build moral courage. TFS allows nurses time to reflect on situations from the clinical setting.

Reflective Practice involves facilitating nurses the opportunity to reflect on the what has occurred in their daily experiences. Studies have shown that reflective practice gives nurses a better understanding of their actions, which subsequently gives them a greater sense of purpose and adds to the development of their nursing skills and increased clinical competency (Smith & Jack, 2005). Reflective practice promotes courage, to meet the needs of unique patients, and helps empower nurses (Gustafsson & Fagerberg, 2004); as well as being a way for nurses to discuss their feelings to better understand why they feel a certain way (Caldwell & Grobbel, 2013). TFS allows nurses a safe space to regularly reflect and receive feedback from a professional.

3. Roy adaptation theoretical concepts

Roy's concept of adaptation is based on scientific, philosophical and cultural assumptions. The scientific premises of Roy's Model are based on Bertalanffy's (1968) general systems theory and Helson's (1964) adaptation theory. Roy recognizes the need to adjust applications of the theory to enhance its relevancy and effectiveness in view of cultural diversity. Roy originated the concept of veritivity (from the Latin word veritas), that innate in human nature is rooted a creative and purposeful drive for a common good that supports the dignity of all people groups and the sacredness of our shared humanity (Roy, 2009).

3.1. Nursing groups as adaptive systems

Primary concepts of the Roy Adaptation Model (RAM) are (a) stimuli, (b) coping processes, and (c) adaptive responses. Roy views the individual or group as a system with components that continually interact with stimuli present in the environment. Coping processes mediate the relationships between the stimuli and the adaptive modes.

3.1.1. Stimuli

Viewing nurses as an adaptive system provides a paradigm by which nurses interact in caring for people groups. Nurses themselves form a people group with care needs. Nurses, as a professional group, possess holistic distinct characteristics, such as, shared responsibilities and goals, a Code of Ethics, normative behaviors and moral statutes. Nurses adapt effectively or maladapt according to events and human interactive stimuli in their environment. The human output responses to the environmental stimuli impact the nurse and provide feedback within the environment and therefore further input into the dynamic environmental system. For nurses, this input or stimuli in the workplace environment may be focal, contextual, or residual.

When focal stimuli are present a response is required, as the individual or group becomes immediately aware of the stimulus. A deterioration in a patient's status may serve as a focal stimulus for a nurse caring for a patient in the emergency department. Contextual stimuli are all of the other stimuli in the situation. A physician's order that a patient with a terminal illness be resuscitated, when the patient requested to the nurse that they did not wish to be on life support in the case of their demise, may serve as contextual stimuli. Residual stimuli are environmental factors, the effects of which are unclear or not validated by those affected by the stimulus. The nurse may feel a sense of moral distress, torn between advocating for the patient and following the doctor's orders.

A nurse may be required to float to a COVID designated unit. This becomes a focal stimulus for the nurse. The nurse is required to respond. A lack of orientation to the COVID unit, having to practice in an unfamiliar setting, a lack of personal protective equipment, a lack of knowledge perhaps in regard to the patient treatment plan may all be contextual stimuli, that is “other stimuli” present in the situation. Residual stimuli are possible uncertain variables. The nurse in this sequence of events may be fearful that they will test positive for the virus and become a potential threat to family members at home, or worse yet die from the virus and leave one's children orphaned.

3.1.2. Coping processes

The regulator and cognator processes are applied to the individual coping processes. The regulator subsystem responds through neural, chemical, and endocrine pathways. Regularly placed in repeated stressful situations, nurses may experience persistent elevated cortisol levels with resulting adrenal fatigue, putting them at risk for exhaustion. The cognator subsystem involves perception, information processing, judgement, and emotional responses.

The stabilizer and innovator subsystems are applied to group coping processes. According to Roy's theory groups have two major purposes that are related to stability and change. Just as there is a homeostatic drive in the individual, there is an adaptive process that drives the group to equalize and stabilize toward a common goal. The innovator subsystem moves toward thriving and growth in the group paradigm.

3.1.3. Adaptive responses

The adaptive response of the nurse will vary within three levels: integrated, compensatory and compromised (Roy, 2009, p. 37). The nurse may use all of one's available resources to meet the responsibilities imposed upon them and experience an integrated response (effective coping). In the second adaptation level, the nurse may compensate and suffer from physiological discomfort or pain, such as gastrointestinal distress or headache. Cohesive groups where there is a strong sense of common goals tend to remain in the community even when there are influences to leave (Kimberly, 1997). Compromised adaptive responses occur when groups suffer from low morale. In this third level of adaptation, the nurse may be compromised and experience mental exhaustion resulting in a leave of absence or permanently leaving the place of employment and the nursing profession.

4. Adaptive modes applied to tea for the soul as a care program for nurses

To date, the RAM has been applied to the nursing care of patients, families and populations. Very few studies have applied the RAM to caring for nurses, either in the realm of self-care or hospital-based programs. The Roy Adaptation Theory Mode of Relating People (Roy, 2009) is comprised of four categories or needs (Physiologic-Physical, Self-Concept/Group Identity, Role Function, and Interdependence). These modes may be applied to the Tea for the Soul care program for nurses as an intervention to care for the individual and corporate needs of professional nurses. As nurses interact within their work environment, their adaptive responses may be compromised as interpreted within the framework of Roy's theory. TFS Program facilitators are positioned to assist nurses toward integrated adaptive responses.

4.1. Roy's 4 adaptive modes of relating people

The modes in the RAM can be thought of as needs. Roy terms the core need of the group identity mode identity integrity. This is defined as the ways in which the group behaviors are congruent with their awareness of the group identity. These congruent behaviors are manifestations of the group's shared goals and values. If a nurse performs an action that demonstrates an awareness of the group identity, this reinforces the group identity and advances the attainment of the group's common purpose and goals. Integral to the application of the RAM is being mindful of the interrelationship of the individual and group identities and the overlapping of the four modes. These concepts are to be viewed as dynamic and each one continually affecting the other.

4.1.1. Physiologic-physical

The adaptation of nurses as a group system are affected by the basic operating resources of their workplace, physical resources, and workload, etc. Prolonged lack of support in a work environment can have dramatically negative consequences for a group over time as has been studied in regard to the effects of moral residue in nurses (Lackman, 2016).

The physical strength and endurance of nurses employed in high patient acuity areas are repeatedly challenged and overtaxed. Twelve-hour shifts, staffing shortages, frequent encounters with death, the threat of violence, and risk of COVID-19 are a few of the stressors nurses are encountering. Nurses need to be regularly recognized and supported for the work they are doing. TFS provides nurses with a brief mechanism for rest,refreshment, and Self-Care within their work facility, whereby a professional can listen to their stories, offer compassion to them, and comfort them in the indispensable work they do. Providing personal feedback to nurses in real-time can revive them and increase their overall sense of well-being. TFS facilitators provide nurses with a Ministry of Presence, a presence that chaplains describe as physical and spiritual as well as pastoral (Sullivan, 2019).

4.1.2. Group identity/shared identity

Shared Identity is a major component of the adaptive process in the Group Identity Mode. A shared group identity is more complex than the sum of the total self-identities of the group individuals and how they relate to one another in the group. Social identity theory (SIT) as a framework for understanding group interactional relations is well established (Reicher et al., 2010). This framework has paved the way of an increasing awareness and dire relevance to apply SIT to the world at large.

SIT is also a basis for social influence or what is called identity-based influence. This means that people are able to exert a more positive influence over others to the extent they are seen as embodied within the social identity to which they belong. This may well apply to the TFS Program facilitator. Viewed by the nurses as a support person and source of council within their group, as a hospital employee and member of the healthcare team, the chaplain may be in a highly effective position to provide encouragement to the nurses, and whose support may be more meaningful than strategies coming from external assistance programs or methods.

Haslam (2014) developed the application of social identity theory to healthcare. He extracted five core lessons from the literature:

(1) Groups and social identities matter because they have a critical role to play in organizational and health outcomes. (2) Self-categorizations matter because it is people's self-understandings in a given context that shape their psychology and behavior. (3) The power of groups is unlocked by working with social identities not across or against them. (4) Social identities need to be made to matter in deed not just in word. (5) Psychological intervention is always political because it always involves some form of social identity management (p. 2).

It is imperative that nursing administrators take an active part in initiating and maintaining programs that meet the emotional needs and enhance the self-awareness of individual nurses, thus fostering the integral social identity of nursing groups within health organizations. Nurse managers are in a primary position to advocate for staff nurses who bear the brunt of traumatic events occurring at the bedside by developing strategies for programs such as TFS that facilitate reflective practice, supportive feedback, and positive action toward a unanimous sense of the collective self, reinforcing the values of the larger organization. Healthy nurses make healthier patients. Ross et al. (2020) used Roy's Adaptation Model as a framework to guide researchers in evaluating depressive symptoms among RNs, stating, “A mentally-healthy nursing workforce is vital to providing quality healthcare” (p. 207).

The adaptation or ineffective behaviors of the nurse may be influenced by self-concept. Psychic and spiritual integrity as defined by Roy, influence the beliefs and feelings one has about themselves and subsequently their behavior. Group-identity is driven by the interpersonal relationships of the group, a sense of shared responsibility, and a solidarity of collective values and a common mission. Sacred Encounters, a term coined by the St. Joseph Health System of Orange in California, describes a way to focus on improving the healthcare system by enhancing the quality of life of the community it serves, as well as bringing the human touch back into the high-tech world of medicine (Catholic Health Association of the United States, 2011).

The TFS counselor is in a key position to reinforce to the nurse how they may be fulfilling their personal call to nursing and aiding in the fulfillment of the institutional mission as a social and collaborative community. Counselors can help nurses reflect on why they went into Professional Practice and how their self-concept can be played out as they work together as a team.

4.1.3. Role function

Social integrity is the basic need underlying the group identity mode of role function. This sense of integrity is influenced by the expectations of the individual in their role in relationship to the group to which they belong. This need is based on the need to know who one is in relationship to those in their workplace, so that they know how to respond. The perception of role function is the means by which the goals of the group, unit or institution are fulfilled, thus unit nurses constitute a primary part of the larger group infrastructure of the hospital. The group role function mode includes nurses, administrators, physicians, and the spiritual care team. The role function of the group's interrelatedness, interprofessional support, and the quality of communication all affect the group's common goals.

The regular presence of a counselor or spiritual care facilitator in the context of the TFS program can provide nurses, together with members of the healthcare team, a common area to gather apart from the workspace; yet nested within the work environment. This communal safe space can serve as “level ground” for the sharing of common goals, like purpose, and an opportunity for Reflective Practice. Reflective Practice is an important part of Professional Practice as previoulsy discussed.Care programs provide a mechanism for nurses to be heard, to learn, and respond to feedback in the development of their capacity to display impactful compassion to patients and families (Smith, et al., 2017). This in turn promotes Improved Patient Care Outcomes essential to nurse role function and nursing excellence.

4.1.4. Interdependence

According to Roy's model the effectiveness of the group interdependence depends on the group interrelatedness in the areas of genuine respect, common values, and caring. The basic need of this mode is the need to feel secure in one's work environment and be a part of relationships that nurture one another. Roy terms this relational integrity. Fulfillment of this need requires resource adequacy. Support systems are integral to adaptation of this group identity mode. Nurses need compassion for the trauma they experience associated with their work environment within the Community. TFS staff offer a means of emotional support to nurses. These staff are trained in therapeutic communication that supports nurses experiencing secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue and moral distress. TFS facilitators model Compassionate Service to nurses thus providing them with a living example of being on the receiving end of compassion. This “filling of their tank” enables nurses to transfer their TFS experience over to their own practice.

5. Conclusion

The Roy Adaptation Theory/Group Identity Mode offers a theory-based framework for the use and effectiveness of the Tea for the Soul Program to address the current needs of nurses employed in the hospital setting. Combining programs that both support nurses within the institutional community environment like Tea for the Soul, and programs that assist nurses individually in self-care, may be the most effective strategy in addressing the well-being of nurses.

Declaration of competing interest

No institutional support, non-commercial grants, commercial support, or support of any kind has been received.

There were no conflicts of interest noted in the compilation of this manuscript.

References

- Ahtisham Y., Quennell S. Usefulness of nursing theory-guided practice: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2019;33(3):540–555. doi: 10.1111/scs.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaker K., Howie-Esquivel, Cataldo J. Relationships among palliative care, ethical climate, empowerment, and moral distress in intensive care unit nurses. American Journal of Critical. 2018;27(4):295–304. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2018252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy L.V. 1968. General system theory: Foundations, development, applications: George Braziller. (revised edition) [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn L., Thompson K., Frankenfield R., Harding A., Lindsey A. The THRIVE program: Building oncology nurse resilience through self-care strategies. Oncology Nurse Forum. 2020;47(1):25–34. doi: 10.1188/20.ONF.E25-E34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning (Callis) A.M. Moral distress and psychological empowerment in critical care nurses caring for adults at end of life. American Journal of Critical Care. 2013;22(2):143-15. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2013437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell L., Grobbel C.C. The importance of reflective practice in nursing. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2013;6(3):319–326. [Google Scholar]

- https://www.chausa.org/publications/catholic-health-world/article/june-1-2011/st.-joseph-caregivers-dig-deep-to-show-authentic-respect

- Corley M.C. Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nursing Ethics. 2002, November;9(6):636–650. doi: 10.1191/0969733002ne557oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S., Webert D., Porter-O’Grady T., Malloch K. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2016. Leadership for evidence-based innovation in nursing and health professions; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler D., Cimini W. Integrating evidence, innovation, and outcomes: The oncology acuity-adaptable unit. Nurse Leader. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2012.12.009. (April, 26-31) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonson C. Moral courage and the nurse leader. The On-line Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2010;15(3) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vo115No03Man05. Manuscript 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elpern E.H., Covert B., Kleinpell R. Moral distress of staff nurses in the medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2005, November;14(6):523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R., Lord H., Halcomb E., Moxham L., Middleton R., Alanzanzeh I., Ellwood L. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses' experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley C.R. Brunner/Mazel Publishing; 1995. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C., Fagerberg I. Reflection, the way to professional development? J of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13(3):271–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamric A.B., Blackhall L.J. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: Collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Critical Care Med. 2007;35(2):422–429. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam A. Making good theory practical: Five lessons for an applied social identity approach to challenges of organizational, health, and clinical psychology. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2014;53:1–20. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson H. Harper & Row; 1964. Adaptation level theory. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderer K., VonRueden K., Friedmann E., McQuillan K., Gilmore R., Kramer B., Murray M. Burnout, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress in trauma nurses. Journal of Trauma Nursing. 2014;21(4):160–169. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseminger K. Overview and summary: Moral courage amid moral distress: Strategies for action. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2010;15(3) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vo115No03ManOS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins B. Concept analysis: Compassion fatigue and effects upon critical care nurses. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2013;35(4):388–395. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e318268fe09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joinson C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing. 1992;22:116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly J.C. University Press of America; 1997. Group processes and structures: A theoretical integration. [Google Scholar]

- Kupperschmidt B., Kientz E., Ward J., Reinholz B. A heathy work environment: It begins with you. The On-line Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2010;15(1) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No01Man03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lackman V. Ethics, law, and policy. Moral resilience: Managing and preventing moral distress and moral residue. Medsurg Nursing. 2016;25(2):121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown B. Mission critical: Nursing leadership support for compassion to sustain staff well-being. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2018;42(3):217–222. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew N., Leske J., Schroeter K. Moral distress in critical care nursing: The state of the science. Nursing Ethics. 2018;25(5):552–570. doi: 10.1177/0969733016664975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana-Rios C., Radbruch L., Kern M., Regel Y., Anton A., Sinclair S., Schmidt S. Mindfulness and compassion-oriented practices at work reduce distress and enhance self-care of palliative care teams: A mixed-method evaluation of an “on the job” program. BMC Palliative Care. 2017;1(3) doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J., Johnson M., Halvorsen B., Apmann L., Chang P., Kershek S., Scherr C. Where do nurses go for help? A qualitative study of coping with death and dying. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2010;16(9):432–438. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.9.78636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijl-Zieber E., Hagen B., Armstrong-Esther C., Hall B., Akins L., Stingl M. Moral distress: An emerging problem for nurses in long-term care? Qual in Ageing. 2008;9(2):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Potter P., Deshields T., Rodriquez S. Developing a systematic program for compassion fatigue. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2013;37(4):326–332. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182a2f9dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Haslam, S. A. (2010). The social identity approach in social psychology. In Wetherell, M. S. & Mohanty, C. T., (Eds.), Sage identities handbook (45–62). Sage. doi:org/ 10.4135/9781446200889.n4. [DOI]

- Ross R., Letvak S., Shepppard F., Jenkins M., Almotairy M. Systematic assessment of depressive symptoms among registered nurses: A new situation-specific theory. Nursing Outlook. 2020;68(2):207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C. 3rd ed. Pearson Education, Inc; 2009. The Roy adaptation model. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton C., Batchellar J., Schroeder K., Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. American Journal of Critical Care. 2015;24(5):412–420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter J., Winch S., Holzhauser K., Henderson A. Nurses' moral sensitivity and hospital ethical climate: A literature review. Nursing Ethics. 2008;15(3):304–321. doi: 10.1177/0969733007088357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A., Jack K. Reflective practice: A meaningful task for students. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(26):33–37. doi: 10.7748/ns2005.03.19.26.33.c3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S., Gentleman M., Conway L., Sloan S. Valueing feedback: an evaluation of a National Health Service Program to support compassionate care practices through hearing and responding to feedback. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2017:112–127. 22(1/2) [Google Scholar]

- Stayt L. Nurses experience bereavement too. Nursing Standard. 2010;24(50):62–63. doi: 10.7748/ns2010.08.24.50.62.p4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan W.F. A Ministry of Presence: Chaplaincy, Spiritual Care, and the Law. University of Chicago Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tranter S., Josland E., Turner K. Nurses’ bereavement needs and attitudes towards patient death: A qualitative descriptive study of nurses in a dialysis unit. Journal of Renal Care. 2016;4(2):101–106. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim W.M., Vico C.L.C., Wai T.C. Experiences and perceptions of nurses caring for dying patients and families in the acute medical admission setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2013;19(9):423–431. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.9.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]