Abstract

The worldwide infection with the new Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) demands urgently new potent treatment(s). In this study we predict, using molecular docking, the binding affinity of 15 phenothiazines (antihistaminic and antipsychotic drugs) when interacting with the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, we tested the binding affinity of photoproducts identified after irradiation of phenothiazines with Nd:YAG laser beam at 266 nm respectively 355 nm. Our results reveal that thioridazine and its identified photoproducts (mesoridazine and sulforidazine) have high biological activity on the virus Mpro. This shows that thioridazine and its two photoproducts might represent new potent medicines to be used for treatment in this outbreak. Such results recommend these medicines for further tests on cell cultures infected with SARS-CoV-2 or animal model. The transition to human subjects of the suggested treatment will be smooth due to the fact that the drugs are already available on the market.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Laser irradiated phenothiazines, Molecular docking

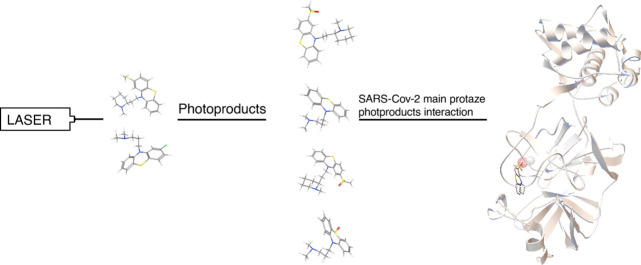

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Binding affinity of 15 phenothiazines with the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is predicted by molecular docking.

-

•

We test the binding affinity of photoproducts identified after irradiation of phenothiazines with Nd:YAG laser beam.

-

•

Thioridazine and its photoproducts, mesoridazine and sulforidazine, have high biological activity on the virus Mpro.

-

•

Results recommend these medicines for further tests on cell cultures infected with SARS-CoV-2 or animal model.

1. Introduction

A virus is an infectious entity that needs, for reproducing, a host cell in a living organism. Viruses constitute a ubiquitous biological entity on our planet [1]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 [2]. WHO report published on 4th of June 2020 (Situation Report-136) shows that there are 3,416,828 confirmed cases worldwide [3]. Since WHO-81 report from 10 April, the number of cases rise accelerated from 92,798 deaths to 157,847 on 20 April [3,4]. The massive number of persons infected by SARS-CoV-2 demands new, more potent treatments.

Drug repositioning is a viable approach instead of developing new drugs in the context of new infectious diseases; this leads to compounds that are de-risked and have lower development costs [5]. In silico studies are a good alternative in an emergent situation to repose a chemical compound [6]. Molecular docking approach is a fast, low-cost procedure used to predict at molecular level the interaction between a ligand and a target [7].

Phenothiazines are chemicals with high antipathogen proprieties against pathogens such as: (i) Protozoa Plasmodium falciparum (protozoan responsible for malaria) [8], genus Leishmania (that cause Leishmaniasis) [9], (ii) several resistant bacterial strains (Multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and (iii) viruses such as those responsible for hepatitis B, HIV, TBEV, arenavirus, herpesvirus etc. [9]. Moreover, in previous epidemies with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS viruses, chlorpromazine (CPZ) shows high inhibitory activity and was recommended as a candidate for testes as a broad-spectrum antiviral [10]. Here, our aim is to propose the antiviral role of phenothiazines against COVID-19.

Phenothiazines like Thioridazine (TZ) and CPZ generate, by exposure to laser radiation, photoproducts that are more efficient in inhibition of bacterial strains than non-irradiated drugs [11].

To find the mechanism of action of TZ after irradiation, we have identified the generated photoproducts. In a previous study, TZ was irradiated up to 11 min with 355 nm Nd:YAG pulsed laser beam which has full-time width at half maximum 5 ns and the average pulse energy on the sample 30 mJ at a repetition rate of 10 pps. Using chromatographic methods (HPLC-MS) we have identified two TZ photoproducts: mesoridazine (MSO) and sulphoridazine (SPZ), those photoproducts are as well TZ metabolites. Molecular structure modifications occur through preferential oxidation in (-SCH3) radical zone [12].

CPZ photoproducts were obtained after irradiation with an Nd:YAG pulsed laser beam at 266 nm with an average pulse energy of 6.5 mJ. The CPZ samples at 2 mg/mL in ultrapure water irradiated 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120,180 and 240 min were analysed using LC-TOF/MS. Results showed seven CPZ generated photoproducts: promazine (PZ), P1, P2, 2-hydroxypromazinesulfoxide (2-HO-PZ-SO), chlorpromazine sulfoxide (CPZ-SO), promazine sulfoxide (PZ-SO) and 2-hidroxipromazine (2-HO-PZ) [13]. We mention that the photoproducts MSO and SPZ may also be used as antipsychotics.

The replications of coronaviruses are blocked by inhibiting the protease of the virus [14]. For identifying a treatment of COVID-19 disease, we used molecular docking procedure to predict the inhibitory activity (against SARS-CoV-2) Mpro of some compounds from phenothiazines drug class. This study also predicts the binding affinity of TZ and CPZ known photoproducts generated by laser irradiation with the Mpro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identify the Viral Protease

To simulate the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and drugs from the class of phenothiazines including TZ and CPZ photoproducts we have used the virus Mpro from RCSB Protein Data Bank: PDB code 6LU7 [15]. The structure of the enzyme was obtained using X-ray diffraction at a resolution of 2.16 Å [15]. We have chosen the Mpro of the virus due to the essential role of this enzyme in proteolytic maturation of the nonstructural proteins. This enzyme represents a potential target in the development of antiviral drugs [16].

2.2. Molecular Docking Protocol

We have prepared the molecule for docking studies by deleting water, adding hydrogen, merging the non-polar hydrogen and adding Gasteiger partial charges [17]. The small molecules were drawn and optimized geometrically using Discovery studio visualizer. After optimization, we have saved the molecules in .mol format [18]. After geometrical optimization, we have used OpenBabel software [19] to shape the molecule in .pdbqt format. For molecular docking approach, we have used Autodock 4.2.6 software [20].

Grid-box was selected to contain only the protease situs identified by amino acids: His 41, Met 49, Phe 140, Asn142 Gly 143, Cys 145, His 163, His 164, Glu 166 and His 172 [21,22]. Covalent grid parameters had an energy barrier height of 1000 and the half-width of 5.00 Å. Total grid Pts per map is 257,725. The grid has the number of points in dimensions: x-60; y-64 and z-64 and the cartesian coordinates of central grid point of maps were set to x = −11.86, y = 17.38, z = 68.99. The spacing of grid points was set to 0.375 Å. For docking simulation, we generated 100 conformations for each ligand; the used search parameter to identify the binding conformation of the ligands was Genetic Algorithm and the output was saved as Lamarckian.

3. Results and Discussions

Generally, a molecular docking result is represented by Estimated Free Energy of Binding (EFEB). Higher biological activity of a drug is correlated with lower free energy of binding [[23], [24], [25]]. Here, EFEB was calculated as EFEB = (1) + (2) + (3)–(4) using Autodock 4.2.6 software where:

-

(1)

is Final Intermolecular Energy vdW + H-bond + desolv Energy Electrostatic Energy.

-

(2)

represents Final Total Internal Energy.

-

(3)

is Torsional Free Energy.

-

(4)

represents unbound System's Energy [=(2)].

Furthermore, the estimated inhibition constant KI was predicted by Autodock 4.2.6 at 298.15 K; a lower KI is correlated with high biological activity (pKI) [26]. For improved data analysis, we converted KI values (nM) in pKI by applying the logarithm function: pKi = log (1/Ki(M)). A pKI value of 4 or lower will define a compound with no biological activity.

TZ presents an estimated Inhibition Constant (Ki) of 244.97 nM (Table 1 ), this energy being lower than EFEB of remdesivir (−7.80 kcal/mol) which is predicted with autodockVina [22].

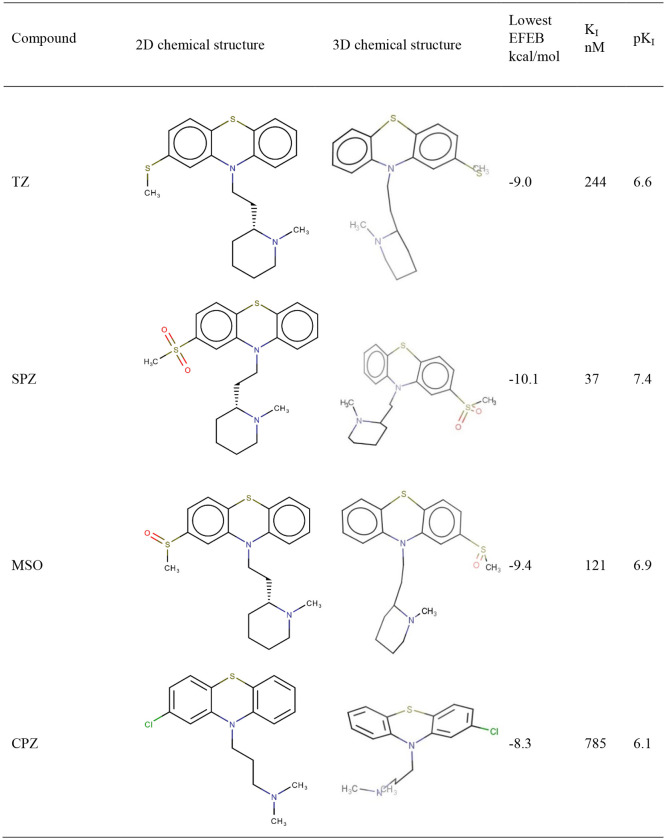

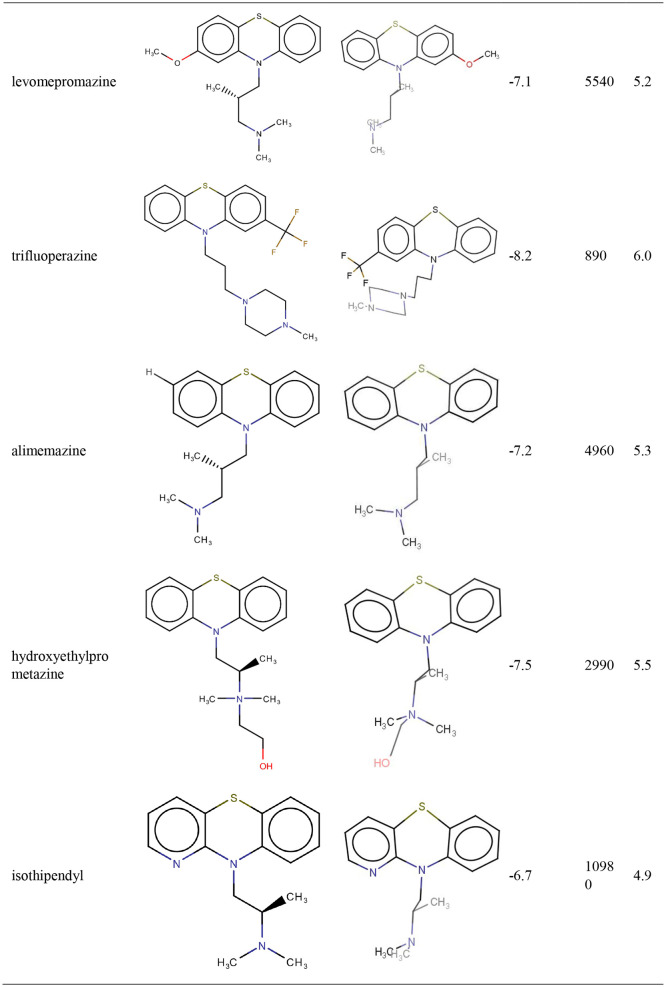

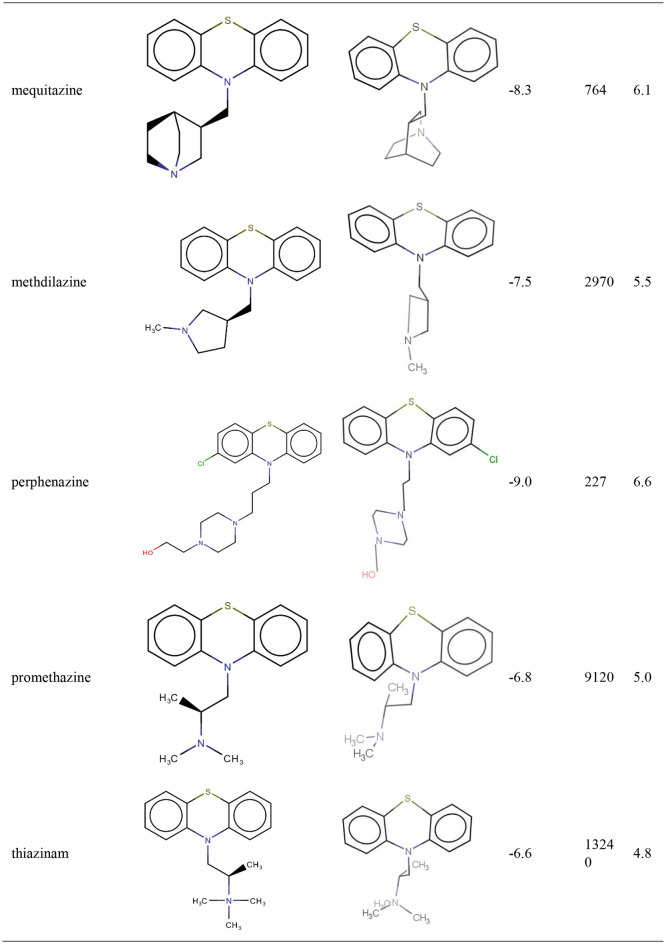

Table 1.

The 2D/3D chemical structure of compounds from Phenothiazines class and TZ and CPZ photoproducts that resulted during laser irradiation; 2D chemical structure, lowest EFEB (kcal/mol) for each compound resulted after 100 runs using molecular docking simulation, predicted KI (nM) and pKI values are also presented. PZ – the acronym of promazine.

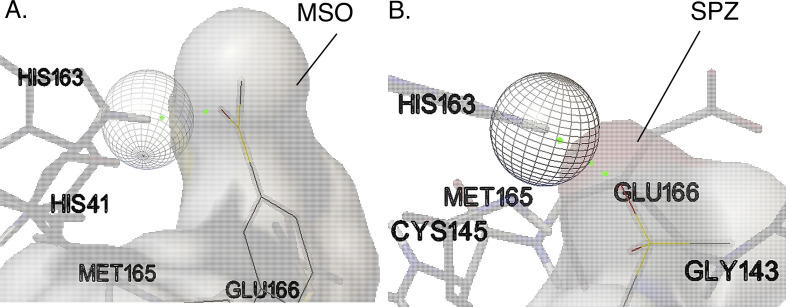

We have compared our results with remdesivir antiviral drug due to improvements showed in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [27]; moreover, remdesivir interacts with the enzyme in the main situs of interaction [22], same as MSO (Fig. 1 ).

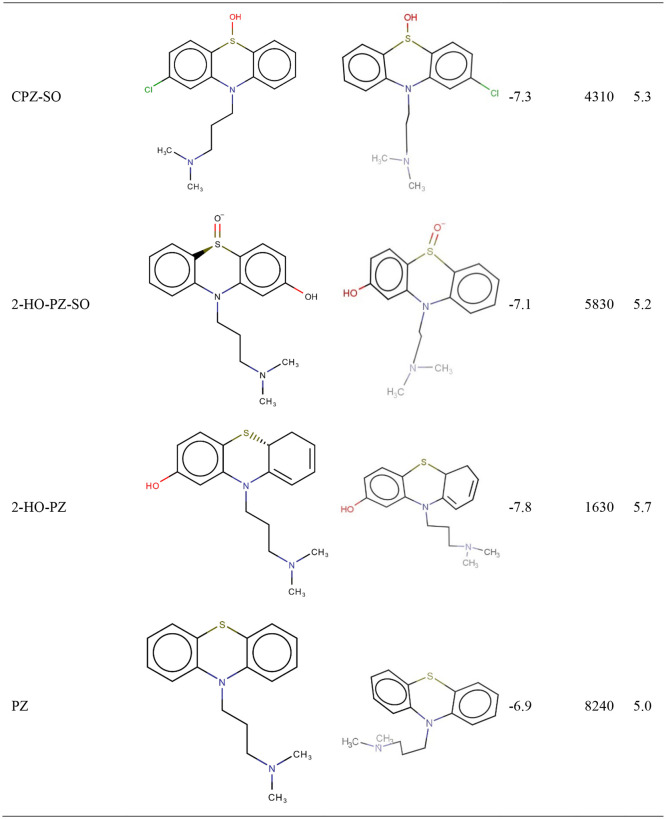

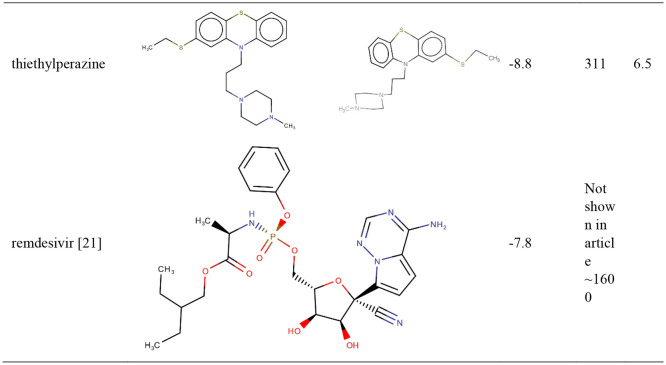

Fig. 1.

3D image of SPZ in the interaction situs of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) [15]. Dotted with red, amino acids from the binding situs of the protease [21,22] situated in close contact at a VDW scaling factor closer than 1. Dotted green line underlines an h-bond interaction between SPZ and His163. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Photoproducts resulted after laser irradiation of TZ present higher biological activities than TZ (Table1).

From Table 1 it results that SPZ presents the highest biological activity on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (pKI = 7.42) and it is in close contact with SARS-CoV-2 amino acids residues from the situs of interaction (Fig. 1).

For a compound with no activity we have used as threshold an EFEB of −6 kcal/mol that represents a KI value of 10,000 nM. As results from Fig. 1, SPZ is in close contact with amino acids: Thr 25, His 41, Tyr 54, Gly 143, Cys 145, His 163, His 164, Met 165, Glu 166, Arg 188 and Gln 198 from which 6 amino acids (HIS 41, GLY 143, CYS 145, HIS 163 HIS 164 and Glu 166) are from the binding situs of the enzyme [21,22].

SPZ forms seven distinct conformational clusters and the number of multi-member conformational clusters is 6, out of 100 runs (Table 2 ). The highest EFEB from 100 runs was −8.48 kcal/mol and the lowest −10.12 kcal/mol.

Table 2.

SPZ conformational clusters, lowest binding energy from each cluster, mean binding energy of the cluster and number of conformations in the cluster.

| Cluster Rank | Lowest Binding Energy kcal/mol | Run | Mean Binding Energy kcal/mol | Number in Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −10.12 | 40 | −9.71 | 43 |

| 2 | −9.80 | 55 | −9.55 | 29 |

| 3 | −9.70 | 65 | −9.70 | 1 |

| 4 | −9.54 | 2 | −9.42 | 5 |

| 5 | −9.54 | 99 | −9.42 | 7 |

| 6 | −9.27 | 90 | −9.25 | 9 |

| 7 | −8.63 | 64 | −8.58 | 6 |

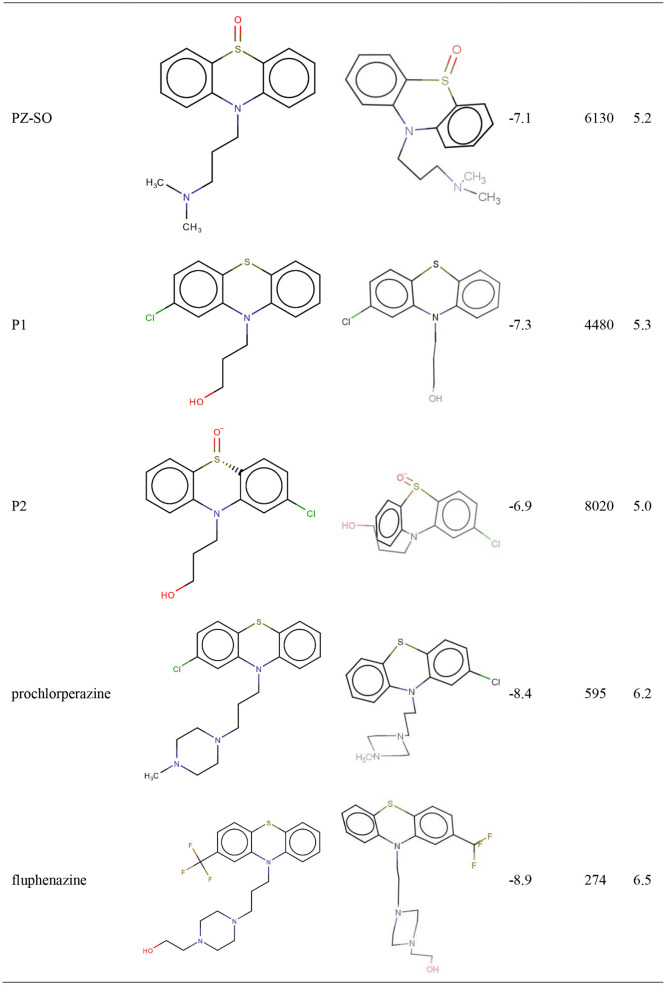

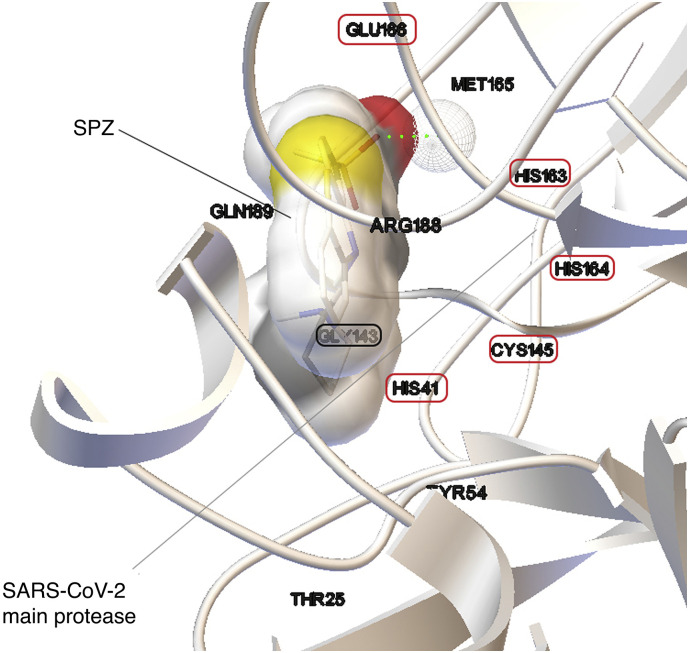

MSO is the photoproduct with the second-highest biological activity (Table 1). It is similar with SPZ and interacts with the Mpro of the virus in the same binding situs and has hydrogen bond interaction with amino acid residue of His 163 (Fig. 2 ). SPZ highest binding energy is −8.72 kcal/mol and the lowest −9.43 kcal/mol (Table1); it forms 9 distinct conformational clusters, and the number of multi-member conformational clusters found is 7.

Fig. 2.

3D images of MSO (A) and SPZ (B) molecules with the lowest KI (MSO KI = 121 nM; SPZ = KI 37 nM) in the run with lowest EFEB energy. Both MSO and SPZ interact with the same amino acid residues (His 163) from the Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) [15] and form a H-bond interaction between Oxygen atom (represented with red) and His 163 (green dotted line) amino acid residues. Except Met 165, all the amino acids residues in close contact presented in this figure in both A and B sections are amino acids from the binding pocket [21,22]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

TZ highest binding energy is −7.06 kcal/mol and the lowest is −9.02 kcal/mol (Table1). The number of distinct conformational clusters is 8 and the number of multi-member conformational clusters that were found is 3. The cluster with the largest number of population (46) had a mean binding energy of −8.22 kcal/mol. Perphenazine antipsychotic drug has the lowest binding energy (−9.06 kcal/mol) similar with TZ (Table1).

CPZ (pKI 6.10) and fluphenazine (pKI 6.56) exhibit a medium biological activity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Table1). CPZ identified photoproducts had a lower biological activity than CPZ. In Table 1 are presented CPZ, fluphenazine and CPZ photoproducts biological activities where other results for tested phenothiazines show medium-low biological activity and are also presented. Compounds that have no biological activity or low biological activities are: (i) the antihistaminic drugs promethazine, thiazinam and isothipendyl; (ii) CPZ photoproducts PZ and P2 compound.

4. Conclusions

Animal models infected with SARS-CoV-2 do not reproduce the same characteristic symptoms as in humans, not even in non-human primates. The animal model, that shows the clinical symptomatology of COVID-19 is represented by a transgenic mouse, that expresses human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. The appearance of clinically observed symptomatology in the trans-genic mouse suggests that this receptor might be responsible for the access of the virus in the human cell [28].

Due to the lack of animal models, and the urgent need of treatment, molecular docking studies are suitable to speed up the process of finding compounds that present possible inhibitory activity.

Our results suggest that TZ and TZ photoproducts obtained by laser irradiation, have significant biological activity on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and could be used in a potent treatment in COVID-19 disease.

According to our previous experience [29], irradiated drugs show better antibacterial activity than non-irradiated drugs and even than photoproducts tested separately. Moreover, the mixture of two obtained photoproducts has improved results compared to a single compound use.

Ergo, we recommend experimental validation of TZ, TZ photoproducts (MSO and SPZ) and irradiated TZ in interaction with SARS-CoV-2, due to the possible increased activity of a combination of such compounds. The use of the “cocktails” of irradiated TZ and its photoproducts might possibly show increased activity on SARS-CoV-2 targets.

Authorship Statement

Manuscript title: Laser Irradiated Phenothiazines: New Potential Treatment for COVID-19 Explored by Molecular Docking.

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, each author certifies that this material or similar material has not been and will not be submitted to or published in any other publication before its appearance in the Journal of Photochemistry & Photobiology, B: Biology.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Mihai Boni and Dr. Tatiana Tozar for their helpful assistance in completing the presentation of the article.

This work was supported by Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research and Innovation, CNCS/CCCDI-UEFISCDI, project PN- III-P1-1.1-PCCDI-2017-0728.

References

- 1.Forterre P. Orig. Defining life: the virus viewpoint. Life Evol. Biospheres. 2010;40(2):151–160. doi: 10.1007/s11084-010-9194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report; 91. Can Be Found under. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200420-sitrep-91-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=fcf0670b_4

- 4.WHO Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report; 81. Can Be Found under. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200410-sitrep-81-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=ca96eb84_2

- 5.Pushpakom S., Iorio F., Eyers P.A., Escott K.J., Hopper S., Wells A., Doig A., Guilliams T., Latimer J., McNamee C., Norris A., Sanseau P., Cavalla D., Pirmohamed M. Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18(1):41–58. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlad I.M., Nuta D.C., Chirita C., Caproiu M.T., Draghici C., Dumitrascu F., Bleotu C., Avram S., Udrea A.M., Missir A.V., Marutescu L.G., Limban C. In Silico and in vitro experimental studies of new Dibenz[b,e]Oxepin-11(6H)one O-(Arylcarbamoyl)-Oximes designed as potential antimicrobial agents. Molecules. 2020;25(2):321. doi: 10.3390/molecules25020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinzi L., Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(18):4331. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalkanidis M., Klonis N., Tilley L., Deady L.W. Phenothiazine Antimalarials: synthesis, antimalarial activity, and inhibition of the formation of β-haematin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;63(5):833–842. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amaral L., Viveiros M., Molnar J. Antimicrobial activity of phenothiazines. In Vivo Athens Greece. 2004;18(6):725–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyall J., Coleman C.M., Hart B.J., Venkataraman T., Holbrook M.R., Kindrachuk J., Johnson R.F., Olinger G.G., Jr., Jahrling P.B., Laidlaw M., Johansen L.M., Lear-Rooney C.M., Glass P.J., Hensley L.E., Frieman M.B. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58(8):4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03036-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexandru T., Armada A., Danko B., Hunyadi A., Militaru A., Boni M., Nastasa V., Martins A., Viveiros M., Pascu M.L., Molnar J., Amaral L. Biological evaluation of products formed from the irradiation of chlorpromazine with a 266 nm laser beam. Biochem. Pharmacol. Open Access. 2013;02 (htt) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smarandache A., Militaru A., Goker H., Pascu A., Pascu M.L. Laser methods for pharmaceutical pollutants removal. In: Schiopu P., Tamas R., editors. Constanta, Romania. 2012. p. 84111E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandru T., Staicu A., Pascu A., Radu E., Stoicu A., Nastasa V., Dinache A., Boni M., Amaral L., Pascu M.L. Characterization of mixtures of compounds produced in chlorpromazine aqueous solutions by ultraviolet laser irradiation: their applications in antimicrobial assays. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014;20(5) doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.5.051002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng X., StJohn S.E., Osswald H.L., O’Brien A., Banach B.S., Sleeman K., Ghosh A.K., Mesecar A.D., Baker S.C. Coronaviruses resistant to a 3C-like protease inhibitor are attenuated for replication and pathogenesis, revealing a low genetic barrier but high fitness cost of resistance. J. Virol. 2014;88(20):11886–11898. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01528-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of Mpro from COVID-19 virus and discovery of its inhibitors. Biorxiv. 2020 doi: 10.2210/pdb6lu7/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi D., Hiromasa Y., Kim Y., Anbanandam A., Yao X., Chang K.O., Prakash O. Structural and dynamics characterization of norovirus protease: NMR study of norovirus protease. Protein Sci. 2013;22(3):347–357. doi: 10.1002/pro.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou X., Du J., Zhang J., Du L., Fang H., Li M. How to improve docking accuracy of AutoDock4.2: a case study using different electrostatic potentials. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, Jan 28;53(1):188–200. doi: 10.1021/ci300417y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA . Dassault Systèmes; 2019. Discovery Studio, [19.1.0.18287], San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A., Morley C., Vandermeersch T., Hutchison G.R. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. Aust. J. Chem. 2011;3(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R, .K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khaerunnisa S., Kurniawan H., Awaluddin R., Suhartati S., Soetjipto S. Potential inhibitor of COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) from several medicinal plant compounds by molecular docking study. Med. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.20944/preprints202003.0226.v1. preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang Y.C., Tung Y.A., Lee K.H., Chen T.F., Hsiao Y.C., Chang H.C., Hsieh T.T., Su C.H., Wang S.S., Yu J.Y., Shih S., Lin Y.H., Lin Y.H., Tu Y.C.E., Hsu C.H., Juan H.F., Tung C.W., Chen C.Y. Potential therapeutic agents for COVID-19 based on the analysis of protease and rna polymerase docking. Med. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.20944/preprints202002.0242.v2. preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Rahman L.H., Abu-Dief A.M., Aboelez M.O., Hassan Abdel-Mawgoud A.A. DNA interaction, antimicrobial, anticancer activities and molecular docking study of some new VO(II), Cr(III), Mn(II) and Ni(II) mononuclear chelates encompassing quaridentate imine ligand. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2017;170:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tripathi S.K., Muttineni R., Singh S.K. Extra precision docking, free energy calculation and molecular dynamics simulation studies of CDK2 inhibitors. J. Theor. Biol. 2013;334:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raha K., Merez K.M., Jr. Chapter 9 calculating binding free energy in protein–ligand interaction. Ann. Rep. Comput. Chem. 2005;1:113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Udrea A.M., Puia A., Shaposhnikov S., Avram S. Computational approaches of new perspectives in the treatment of depression during pregnancy. Farmacia. 2018;66(4):680–697. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kujawski S.A., Wong K.K., Collins J.P., Epstein L., Killerby M.E., Midgley C.M., Abedi G.R., Ahmed N.S., Almendares O., Alvarez F.N., Anderson K.N., Balter S., Barry V., Bartlett K., Beer K., Ben-Aderet M.A., Benowitz I., Biggs H., Binder A.M., Black S.R., Bonin B., Brown C.M., Bruce H., Bryant-Genevier J., Budd A., Buell D., Bystritsky R., Cates J., Charles E.M., Chatham-Stephens K., Chea N., Chiou H., Christiansen D., Chu V., Cody S., Cohen M., Conners E., Curns A., Dasari V., Dawson P., DeSalvo T., Diaz G., Donahue M., Donovan S., Duca L.M., Erickson K., Esona M.D., Evans S., Falk J., Feldstein L.R., Fenstersheib M., Fischer M., Fisher R. First 12 Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. Public Global Health. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.09.20032896. preprint. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan S., Siddique R., Shereen M.A., Ali A., Liu J., Bai Q., Bashir N., Xue M. The emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), their biology and therapeutic options. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00187-20. (JCM.00187-20, jcm;JCM.00187-20v1, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32161092) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tozar T., Nastasa V., Stoicu A., Chifiriuc M.C., Popa M., Kamerzan C., Pascu M.L. In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of laser exposed chlorpromazine against gram-positive Bacteria in planktonic and biofilm growth state. Microb. Pathog. 2019;129:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]