Abstract

Microwave-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds (TKMSP) was optimized using Response surface methodology (RSM) base on Central composite design (CCD). The optimum extraction conditions are detailed as follows: liquid-solid ratio 42 mL/g, extraction temperature 80 °C, microwave power 570 W, extraction time 26 min. Under this conditions, the mean value of TKMSP yield 2.43 ± 0.45% (n = 3), which was consistent closely with the predicted value (2.44%). The five polysaccharides (TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2, TKMSP-3, TKMSP-4 and TKMSP-5) were isolated from TKMSP by DEAE-52. TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2 and TKMSP-4 were common in containing Man, Rib, Rha, GluA, GalA, Glu, Gal, Xyl, Arab and Fuc. However, there was no Fuc in TKMSP-3, while TKMSP-5 lacked GluA, GalA and Fuc. UV–vis and FT-IR analysis combined with molecular weight determination further indicated that the five fractions were polydisperse polysaccharides. A significant difference was achieved in the structural characterization of these five fractions. TKMSP exhibited immunosuppressive activity on RAW264.7 cells. It can be applied as a potential immunosuppressant agent in medicine.

Keywords: Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds, Polysaccharides, Immunomodulatory activity, Microwave-assisted extraction

Highlights

-

•

Microwave-assisted extraction of TKMSP optimized by RSM base on CCD.

-

•

The five polydisperse polysaccharides were isolated from TKMSP.

-

•

The structure characterizations of the five polysaccharides were analyzed.

-

•

TKMSP-3 exhibited significant inhibition of RAW264.7 proliferation.

1. Introduction

The immune system plays an important system role in immune response. Overzealous immune responses can lead to autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1,2]. Recently, the respiratory failure caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) a leading cause for the high mortality of COVID-19. Several studies suggested that the overzealous immune responses associated with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or cytokine storm, also known as secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis (sHLH), may be driving COVID-19 related ARDS [[3], [4], [5]]. Although several immunosuppressants have been found, most of them have side effects, such as cyclosporine, Tacrolimus [6], methylprednisone [7], etc. Therefore, it is crucial to find a natural immunosuppressive agent.

Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim belongs to Cucurbitaceae, and is mainly distributed in Liaoning, Anhui, Shandong, Henan and other places in China [8]. The root and peel of Trichosanthes kirilowii have been studied and developed into drugs widely applied in clinic. Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds (TKMS) is one of Chinese traditional medicine, also known as “drug homologous food”, which has been commonly used in the treatment of cough, constipation, inflammation, etc. At present, the research on TKMS mainly focused on its oils [9], flavonoids [10], phenylpropanoids [11], proteins, etc. [12], while its carbohydrates are seldom studied. Polysaccharides exhibit varieties of biological activity existing in almost all organisms, such as antioxidant [13], antitumor and immunomodulation activities [14] and so on. Recently, researches have been investigated about potential applications of polysaccharides isolated from various seeds, such as Pinus halepensis Mill. seeds [15], Chaenomeles speciosa seeds [16] and Z. jujuba cv. Ruoqiangzao seeds [17], all of which show the potential immunomodulatory activity and the high value of research. However, there are still few researches focusing on the extraction, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds (TKMSP).

There are various methods available for the extraction of polysaccharides, including microwave, ultrasonic, enzymatic, and water extraction. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) is an important method to extract polysaccharide from seeds,which has the advantages of short extraction time, high yield, excellent quality of final product, low solvent consumption and labor-saving [18]. Response surface methodology (RSM), as a collection of statistical techniques including experiment designing, model building, evaluation of factors, and the search for optimal conditional factors, is applied to determine the influence of each factor and its interaction on the extraction rate and identify the optimal conditions statistically. The main superiority of the RSM is to reduced times of experiments required during the optimization process [19]. Central composite design (CCD) of response surface methodology, as a statistical tool, is applied to study the influence of input parameters on process outputs and to identify the most effective parameters [20]. Compared with the traditional Box-Benhnken design (BBD), CCD exhibits various advantages, including less testing times, being able to evaluate the nonlinear effects of various factors, being applicable to all tested factors and so on.

In this study, the parameters during the process of microwave-assisted extraction of TKMSP were optimized by RSM base on CCD. Then, five fractions of TKMSP were isolated using a DEAE-52 column, in which monosaccharide composition, molecular weight, structures characteristics were determined by a variety of instrumental analysis techniques. Finally, the immunomodulating effects of five fractions were investigated, thus providing a theoretical basis for the further research on the application and development of TKMSP.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds were purchased from Liaoning Province, China and stored in the Engineering Research Center for Agricultural Resources and Comprehensive Utilization of Jilin Provence, Jilin Institute of Chemical Technology, China. All the chemicals and solvents used in the study were analytical reagent grades.

2.2. Extraction of crude polysaccharides

The crude polysaccharides extraction from the seed of Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim was performed by microwave-assisted process in a microwave extraction apparatus (Sineo Microwave Chemistry Co. Ltd., Tianjin, China) [21] with the extraction conditions:Liquid-solid ratio (10:1, 20:1, 30:1, 40:1 and 50:1 mL/g), extraction temperature (50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, 80 °C and 90 °C), microwave power (250 W, 500 W, 600 W, 700 W, 800 W and 800 W) and extraction time (10 min, 15 min, 20 min, 25 min, 30 min and 35 min). The extract solution was obtained by filtering solid residue. A rotary evaporator under reduced pressure was employed to concentrate the filtrate equal to 1/5 of its original volume, followed by precipitation through the addition of certain amount of ethanol (95%, v/v) until the ethanol to a final concentration of 80% (v/v) storing at 4 °C overnight. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 15 min), which was then re-dissolved in deionized water and dialyzed in a dialysis bag (Mw: 8000–14,000 Da, YTKH life sciences, USA) and lyophilized to obtain polysaccharides from the Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds (TKMSP). The polysaccharide content was measured by the phenol-sulfuric method, where glucose was served as the standard [22]. The polysaccharide yield was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

C (mg/mL) is the concentration of polysaccharide by the calibrated regression equation; Where V (mL) is the volume of the extraction solution; W (g) is the weight of the raw materials; and N is the dilution factor.

2.3. Experimental design and statistical analysis

The primary variable range was determined by single-factor-test including X1 (liquid-solid ratio, mL/g), X2 (extraction temperature, °C), X3 (microwave power, W) and X4 (extraction time, min). According to the results of single-factor-test and design principle of the response surface center, combination design (CCD) was conducted to optimize the process [23] while the polysaccharide yield was treated as a response value. The whole design contains twenty-one experimental runs, which were represented by the coded and non-coded values of the experimental variables as shown in Table 1 . All trials were performed in triplicate. The quadratic polynomial was used to express the response (Y) as a function of the independent variables:

| (2) |

where X i and X j denote the different independent variables. Y 0 is the predicted response. β 0, β j, β jj and β ij denote the regression coefficients corresponded to intercept, linearity, square, and interaction, respectively.

Table 1.

The coded level of three variables and their response values for the yield of TKMSP based on CCD.

| No. | X1 (Liquid-solid ratio, mL/g) | X2 (Extraction temperature, °C) | X3 (Microwave power, W) | X4 (Extraction time, min) | Polysaccharide yield (%) | Predicted Value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 2.29 | 2.40 |

| 2 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 2.49 | 2.40 |

| 3 | 1 (50) | 1 (90) | −1 (500) | −1 (20) | 1.34 | 1.31 |

| 4 | 1.682 (56.81793) |

0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| 5 | 0 (40) | −1.682 (63.18207) |

0 (600) | 0 (25) | 1.52 | 1.52 |

| 6 | 1 (50) | −1 (70) | 1 (700) | 1 (30) | 1.38 | 1.41 |

| 7 | −1 (30) | 1 (90) | −1 (500) | 1 (30) | 1.43 | 1.40 |

| 8 | −1 (30) | −1 (70) | −1 (500) | −1 (20) | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| 9 | −1.682 (23.18207) |

0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 1.26 | 1.26 |

| 10 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 2.41 | 2.40 |

| 11 | 1 (50) | −1 (70) | −1 (500) | 1 (30) | 1.50 | 1.47 |

| 12 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | −1.682 (16.59104) |

0.99 | 0.99 |

| 13 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 2.39 | 2.40 |

| 14 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 0 (25) | 2.42 | 2.40 |

| 15 | 0 (40) | 1.682 (96.81793) |

0 (600) | 0 (25) | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| 16 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 0 (600) | 1.682 (33.40896) |

1.54 | 1.54 |

| 17 | 1 (50) | 1 (90) | 1 (700) | −1 (20) | 1.25 | 1.28 |

| 18 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | 1.682 (768.1793) |

0 (25) | 2.25 | 2.18 |

| 19 | −1 (30) | 1 (90) | 1 (700) | 1 (30) | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| 20 | −1 (30) | −1 (70) | 1 (700) | −1 (20) | 1.24 | 1.27 |

| 21 | 0 (40) | 0 (80) | −1.682 (431.8207) |

0 (25) | 2.19 | 2.25 |

Note: The actual parameters are shown in brackets.

The experimental design, data analysis and modeling were conducted by the Design-Expert Software Version 8.0.6.1. The quadratic polynomial model was fitted by the regression coefficient R 2. F-value and P-value were employed to examine the significance of the regression coefficient.

2.4. Purification of polysaccharide

The polysaccharide was deproteinized by Sevag using the previous method [28]. Briefly, the 20 mL Sevag reagent (chloroform: n-butyl alcohol = 4:1, v/v) was added to crude TKMSP (500 mg) solution dissolving in deionized water (100 mL). Then the mixed solution was shaken in a 30 °C constant temperature shaker at 200 r/min for 30 min. The supernatant of deproteinized polysaccharide was obtained by centrifugation at 3000 r/min for 10 min. This process was repeated three times. Finally, the supernatant was condensed into TKMSP concentrate after deproteinization (about 5 to 10 mL) as standby. The TKMSP concentrate was loaded onto a Cellulose DEAE-52 column (26 mm × 300 mm), followed by a stepwise elution with increased concentrations of NaCl (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 M NaCl) at a rate of 1 mL/min. The each eluate (5 mL/tube) was collected, and monitored at 490 nm by the phenol-sulfuric acid method. Then the homogeneous fraction was collected, followed by dialysis bags using ultrapure water for 24 h, which was lyophilized to obtain purified polysaccharide for next analysis. Finally, the phenol‑sulfuric acid method is applied to calculate the carbohydrate content based on glucose standard sample and uronic acid quantity was confirmed by meta-hydroxydiphenyl assay [24]. The Bradford assay was employed to calculate the amount of protein where bovine serum albumin was a standard reagent [25].

2.5. UV–vis and FT-IR spectra analysis

The UV–vis spectrum was recorded in the wavelength range of 200–600 nm using a 759S spectrophotometer (Shanghai Lengguang Technology Co., Ltd., China). The polysaccharide (2 mg) was incorporated with KBr powder (100 mg), which was then pressed into a tablet for FT-IR analysis (Gangdong SCI. & TECH. Development Co. Ltd., Tianjin, China) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.6. Monosaccharide compositions and molecular weight analysis

The released monosaccharides were labeled with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5- pyrazolone (PMP) [26]. Briefly, each sample (2 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 2 mol/L trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and hydrolyzed in a sealed condition at 120 °C for 2 h in a hydrothermal reactor. Then the residual was washed by coevaporation using ethanol to remove the excessive trifluoroacetic acid. Next, the hydrolysate solution was mixed with 200 μL 0.5 mol/L methanol solution of 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone (PMP, methanol as solvent) and 200 μL 0.3 mol/L NaOH solution, followed by reaction for 60 min at 70 °C. The reaction was quenched by neutralizing with 200 μL 0.3 mol/L HCl. Finally, the product was extracted three times with 1 mL chloroform. The aqueous layer containing PMP-labeled derivative was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane for HPLC analysis. The Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo, USA) equipped with an Ultimate 3000 diode array detector (DAD, Thermo) was employed to detect PMP labeled monosaccharides. The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile (A) and 0.1 mol/mL phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 6.7) in a ratio of 82:18 (v/v). With 20 μL of injection volume, the samples were performed on a Supersil ODS2 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm2) at 30 °C with 0.8 mL/min of flow rate and detected at 245 nm. Different types of monosaccharide were used as standards (Mannose, Ribose, Rhamnose, Glucuronic acid, Galacturonic acid, Glucose, Galactose, Xylose, Arabinose and Fucose).

The molecular weight of the samples was measured using high performance gel permeation chromatography associated with a refractive index detector (HPGPC-RID) as described previously [27]. 20 μL sample solution (2.0 mg/mL) was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter, which was determined by HPLC (Elite P230IIHPLC, Elite Analytical Instruments Co. Ltd., Dalian, China) equipped with a Shodex sugar KS-804 column (8.0 mm × 300 mm) and a refractive index detector (RID) (RI2000, A, Schambeck SFD GmbH, Germany). The columns were maintained at 50 °C and eluted with ultrapure water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Data processing was recorded on an N2000 GPC. The molecular weight of sample was calculated by the calibration curve obtained by various standard dextrans with different molecular.

2.7. Congo red test

The conformational structure of purified polysaccharide was determined by the previous Congo red method [28]. Briefly, each sample solution (2.0 mL, 2 mg/mL) was mixed with 2.0 mL of Congo red solution (80 μmol/L). Then NaOH solution (1 mol/L) was added to the mixture gradually to achieve the final concentration of 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 mol/L NaOH, respectively. After keeping the mixture at room temperature for 5 min, the UV–vis spectrum was recorded by using 759S spectrophotometer in the range of 200–800 nm and maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) was identified.

2.8. Immunomodulatory activity on RAW264.7 cells

2.8.1. Cell culture

The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells were purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were grown in DMEM medium (10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate,), then were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The cells were cultured for 48 h and kept in logarithmic phase.

2.8.2. Cell viability assay

The cell viability of polysaccharides were evaluated by methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay [29]. In brief, the RAW264.7 cells suspensions (concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded onto 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. After discarding the supernatant, the cells were treated with 100 μL samples with the final concentration of 25–800 μg/mL. The complete medium no added polysaccharide was employed as the blank control, then 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well. The incubation was continued for another 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Afterwards, the supernatants were removed and the produced formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After shaking, the plates were placed in the dark for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm and calculated as follows:

| (3) |

Finally, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of polysaccharides on RAW264.7 cells was calculated.

2.8.3. Phagocytosis assay

Phagocytosis activity was evaluated by neutral red [30]. The cells were cultivated to different concentrations of sample for 24 h as described above. Then, the plates were washed by PBS, and 100 μL neutral red solutions were added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 h, the supernatants were discarded and the cells were washed by PBS. Then 100 μL cell lysis solution (ethanol and 1.0 mol/L acetic acid at 1:1 ratio) was added, and placed overnight at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm. The phagocytosis index was calculated as follows:

| (4) |

2.9. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was carried out on SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used by GraphPad Prism. P-values <0.01 were considered as extremely significant statistical difference. P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant difference.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Single factor experimental analysis

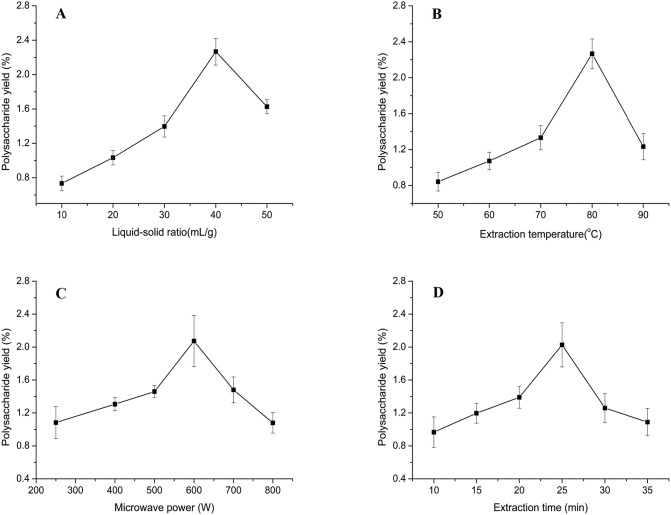

The effect of the liquid-solid ratio on the TKMSP yield is illustrated in Fig. 1A, extraction parameters was used as follows: extraction temperature 80 °C, microwave power 600 W and extraction time 25 min. The results indicated a positive linear trend for the effect on the TKMSP yield when the liquid-solid ratio ranged from 10 to 40 mL/g, and reached its maximum (2.27 ± 0.16%) when the liquid-solid ratio of 40 was employed. This could be attributed to the fact that the increased liquid-solid ratio enhanced the dissolution of polysaccharides from seeds. However, with the increase of liquid-solid ratio, the extraction rate of polysaccharide decreased, which is due to the larger concentration difference between the plant intracellular and extracelluar solvents, further reducing the molecular interaction effect [31].

Fig. 1.

Effect of different liquid-solid ration (A), extraction temperature (B) and microwave power (C) and extraction time (D) on the polysaccharides yield.

The polysaccharide yield of TKMSP could be influenced by different extraction temperature from 50 to 90 °C and a liquid-solid ratio of 40 mL/g, a microwave power of 600 W and an extraction time of 25 min as shown in Fig. 1B. The results demonstrated that the yield of TKMSP was enhanced to maximum production (2.26 ± 0.17%) at 80 °C and then decreased with the increased temperature due to the hydrolysis of polysaccharides at a high temperature [32]. Therefore, the best extraction temperature was determined to be about 80 °C.

As shown in Fig. 1C, the effect of microwave power on polysaccharide yield was investigated. The other factors including liquid-solid ratio, extraction temperature and time were fixed at 40 mL/g, 80 °C and 25 min, respectively. The results indicated that the polysaccharide yield increased with the enhanced microwave power from 250 to 600 W, then reaching its maximum (2.07 ± 0.31%) when the microwave power of 600 W was employed. This is due to the fact that enhanced microwave power will improve the solubility of sample. Meanwhile, with the enhancement of in microwave power would increase the dipole rotations, which leads to the increased thermal energy in the reaction mixture, thus enhancing the yield polysaccharide yield. However, too high microwave power will destroy the structure of polysaccharide, which will lead to the decrease of extraction rate [33].

As shown in Fig. 1D, the influence of extraction time on TKMSP yield was studied under certain conditions (liquid-solid ratio of 40 mL/g, microwave power of 600 W and temperature of 80 °C). It can be noted that the yield of TKMSP increased with the prolonged extraction time from 10 to 25 min, where it reached 2.02 ± 0.27%. This could be attributed to the increased amount of reactive sites induced by the prolonged time, resulting in the improved yield. However, it has decreased when the time extraction time from 25 to 35 min, suggesting that the long extraction time induced polysaccharide degradation [34].

3.2. Model fitting and statistical analysis

The values of polysaccharide yield to different levels combinations of the variables are also shown in Table 1. Based on multiple regression analysis of the experimental data, the predicted variables and the coded independent variables were related by the second-order polynomial equation as follows:

where X1, X2, X3 and X4 denote the liquid-solid ratio (mL/g), microwave power (W), extraction temperature (°C) and extraction time (min), respectively.

The ANOVA for the fitted quadratic polynomial model of extraction of TKMSP is shown in Table 2 . The model F-value of 68.87 and P-value <0.0001 indicated the response surface quadratic model was significant. The values of the regression coefficient (R 2), the value for adjusted coefficient of determination (R 2 adj) and coefficient of variance (C.V.) was 0.9938, 0.9794 and 4.64% respectively, which demonstrated that a high degree of precision and reliability of the experimental values and a high degree of correlation between the observed and predicted values [35]. Furthermore, the lack of fit value also demonstrated the significance of model to the experiment. The significance of each coefficient was determined using F-value and P-value. It could be seen that the quadratic coefficients (X1 2, X2 2 and X4 2) exhibited a high significant effect (P < 0.001), the linear coefficients (X1 and X4) had very significant effect (P < 0.01). The linear coefficient (X2), cross-product coefficients (X2X3 and X3X4) and quadratic coefficients (X3 2) were significant effect (P < 0.05). Instead, the other term coefficients were not significant (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

ANOVA for response surface quadratic model for the yield of TKMSP.

| Source | Sum of squares | Df | Mean square | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 5.73 | 14 | 0.41 | 68.87 | <0.0001⁎⁎⁎ |

| X1 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 24.56 | 0.0026⁎⁎ |

| X2 | 0.036 | 1 | 0.036 | 6.14 | 0.0480⁎ |

| X3 | 0.00612 | 1 | 0.00612 | 1.03 | 0.3492 |

| X4 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 25.47 | 0.0023⁎⁎ |

| X1X2 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.035 | 5.84 | 0.0522 |

| X1X3 | 0.0001125 | 1 | 0.0001125 | 0.019 | 0.8950 |

| X1X4 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.016 | 2.66 | 0.1541 |

| X2X3 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 | 10.02 | 0.0194⁎ |

| X2X4 | 0.009768 | 1 | 0.009768 | 1.65 | 0.2469 |

| X3X4 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 11.84 | 0.0138⁎ |

| X12 | 1.43 | 1 | 1.43 | 240.69 | <0.0001⁎⁎⁎ |

| X22 | 1.94 | 1 | 1.94 | 327.11 | <0.0001⁎⁎⁎ |

| X32 | 0.064 | 1 | 0.064 | 10.73 | 0.0169⁎ |

| X42 | 2.43 | 1 | 2.43 | 408.63 | <0.0001⁎⁎⁎ |

| Residual | 0.036 | 6 | 0.005938 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.015 | 2 | 0.007413 | 1.43 | 0.3409 |

| Pure error | 0.021 | 4 | 0.0052 | ||

| Correlation total | 5.76 | 20 | |||

| R2 | 0.9938 | R2Adj | 0.9794 | ||

| C.V. % | 4.64 | Pred R-Squared | 0.8503 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

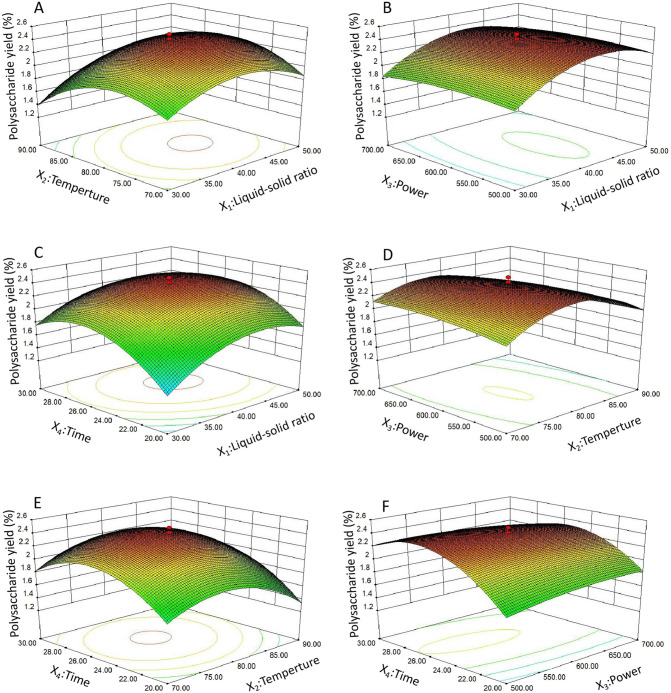

3.3. Analysis of response surface plots and contour plots

The interactive effects of the operational parameters on the TKMSP yield were investigated through a three-dimensional response surface (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) contour plots, which was shown in Figs. 2 and 3 . The 3D graph is used to express the relationship between variables and response values and their interaction. In terms of 2D contour plots, the interactions between the variables represented by an elliptical contour plot are significant. On the contrary, a circular contour plot suggests the interactions are negligible [36]. The TKMSP yield was expected to be sensitive to the alteration of the variables.

Fig. 2.

Response surfaces plots (A–F) showing the effect of variables (X1: liquid-solid ration mL/g; X2: temperature, °C; X3: power, W; and X4: time, min) on the TKMSP yield.

Fig. 3.

Contour plots (A–F) showing the effect of variables (X1: liquid-solid ration mL/g; X2: temperature, °C; X3: power, W; and X4: time, min) on the TKMSP yield.

As shown in Figs. 2A and 3A, it indicated that the mutual interactions between liquid-solid ratio and extraction temperature were insignificant under the zero level of extraction power and extraction time. The effects of the liquid-solid ratio and microwave power on the yield of TKMSP can be found in Figs. 2B and 3B, which indicated that the influence of their interaction was not significant when extraction temperature and extraction time was fixed at zero level. Similarly, the mutual interaction between liquid-solid ratio and extraction time was not significant on yield are shown in Figs. 2C and 3C when the extraction temperature and microwave power was fixed to be level 0. The effects of extraction temperature and microwave power on the yield of TKMSP are shown in Figs. 2D and 3D, it showed that both of the two factors could affect the TKMSP yield distinctly. As shown in Figs. 2E and 3E, when the liquid-solid ratio and microwave power was fixed at level 0, the variations of yields were insignificant with increased extraction temperature and prolonged extraction time. As shown in Figs. 2F and 3F, the TKMSP yield was found to be significantly affected by the enhanced microwave power under a longer extraction time.

3.4. Verification of predictive model

The optimized values of the selected variables were obtained by solving the regression equation using the Design-Expert Software. The suitability of the model equation for predicting optimum response value was investigated under the following optimal conditions: liquid-solid ratio 42.34 mL/g, extraction temperature 79.75 °C, microwave power 569.02 W, extraction time 26.08 min, respectively. The maximum predicted yield was determined to 2.44%. Considering the operation in actual production, the optimal conditions could be modified as follows: liquid-solid ratio of 42 mL/g, extraction temperature of 80 °C, microwave power of 570 W, extraction time of 26 min. Under this conditions, the mean value of TKMSP yield 2.43 ± 0.45% (n = 3) was obtained. The results confirmed the validation of the response model and the suitability of the optimal conditions for TKMSP extraction. In addition, the yield of TKMSP was increased by about 1.00% compared with that before optimization (1.39 ± 0.21%), indicating that the yield of TKMSP was significantly improved by optimizing the extraction process.

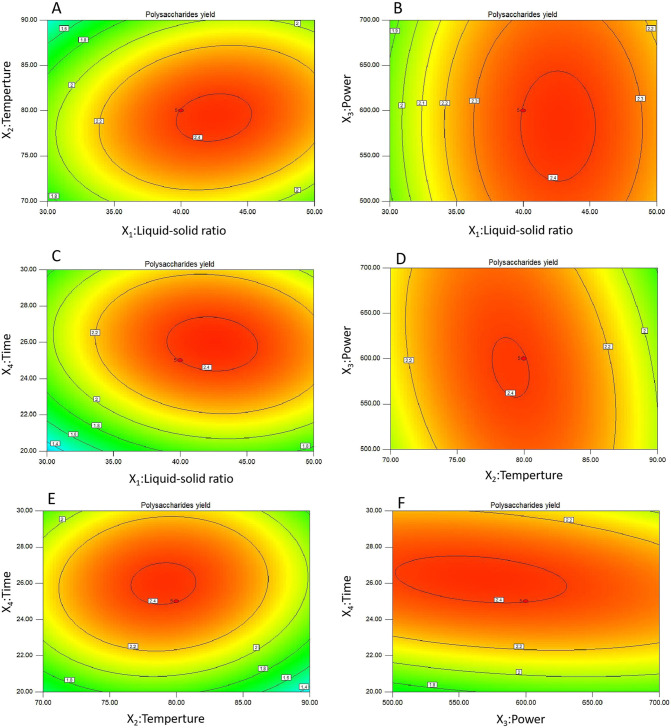

3.5. Purification of polysaccharides

Purified TKMSP was obtained by Sevag method and dialysis. Then, TKMSP were isolated on an anion-exchange DEAE-52 cellulose column as shown in Fig. 4A. Five main fractions termed as TKMSP-1 (15.2 mg), TKMSP-2 (8.1 mg), TKMSP-3 (20.3 mg), TKMSP-4 (9.5 mg) and TKMSP-5 (18.2 mg) were clearly separated by deionized water, 0.1 M, 0.2 M, 0.4 M and 0.5 M NaCl respectively. Subsequently, five main polysaccharide fractions were obtained for further study by concentration, dialysis and lyophilization process.

Fig. 4.

Elution profile of polysaccharides on DEAE-52 cellulose column (A); UV spectra (B) and FTIR spectra (C) of five fractions; changes in absorption wavelength maximum of mixture of Congo red and five fractions at varying NaOH concentrations (D).

The chemical constituents of crude TKMSP, purified TKMSP and five fractions were investigated. The results are presented in Table 3 , the protein content of crude TKMSP was reduced from 9.07 ± 2.54% to 2.18 ± 0.63% after preliminary purification. The purity of the five fraction was 84.13 ± 3.44%, 80.32 ± 4.06%, 82.78 ± 3.59%, 80.43 ± 1.89% and 85.51 ± 1.97% respectively, which were more than 80%. It is worth noting that no uronic acid was detected in the TKMSP-5.

Table 3.

Chemical analysis of polysaccharides.

| Samples | Carbohydrate (%) | Uronic acid (%) | Protein (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude TKMSP | 37.42 ± 2.84% | 5.67 ± 1.84% | 9.07 ± 2.54% |

| Purified TKMSP | 49.23 ± 2.28% | 7.36 ± 1.92% | 2.18 ± 0.63% |

| TKMSP-1 | 84.13 ± 3.44% | 4.54 ± 1.02% | 0.37 ± 0.04% |

| TKMSP-2 | 80.32 ± 4.06% | 2.29 ± 0.65% | 0.55 ± 0.03% |

| TKMSP-3 | 82.78 ± 3.59% | 5.58 ± 0.32% | 0.29 ± 0.04% |

| TKMSP-4 | 80.43 ± 1.89% | 3.74 ± 0.46% | 0.37 ± 0.02% |

| TKMSP-5 | 85.51 ± 1.97% | – | 0.68 ± 0.12% |

3.6. Analysis of UV–vis and FT-IR spectra

The UV–vis spectra of TKMSP were shown in Fig. 4B. The absorption peaks locating at 280 nm of five fractions UV–Vis spectra are all observed, indicating the existence of traced protein. The FTIR spectra of TKMSP were shown in Fig. 4C, the five fractions exhibited similar absorption bands. The strong characteristic absorption band around 3400 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of O—H [37]. The band around 2930 cm−1 was ascribed to the asymmetrical C—H stretching vibration [38]. No absorption at about 1730 cm−1 was observed, implying the absence of uronic acid or less content of uronic acid [39]. The strong absorption at 1650 cm−1 and 1545 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of the carbonyl bond of the amide group and the bending vibration of the N—H bond, respectively, proving the presence of protein. The stretching vibrations of C−O−C and C−O−H contributed the strong absorption band ranging from 1000 to 1200 cm−1 [40]. The strong peaks locating at 1130 cm−1 and 1078 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibration of pyranose ring [41]. The absorption peak of TKMSP-4 and TKMSP-5 at around 860 cm−1 is a characteristic absorption of polysaccharides, an indicator of the α-type glycosidic linkage [42], while negligible peak of TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2 and TKMSP-3 were achieved. The results showed that the functional groups of the five fractions were slightly different.

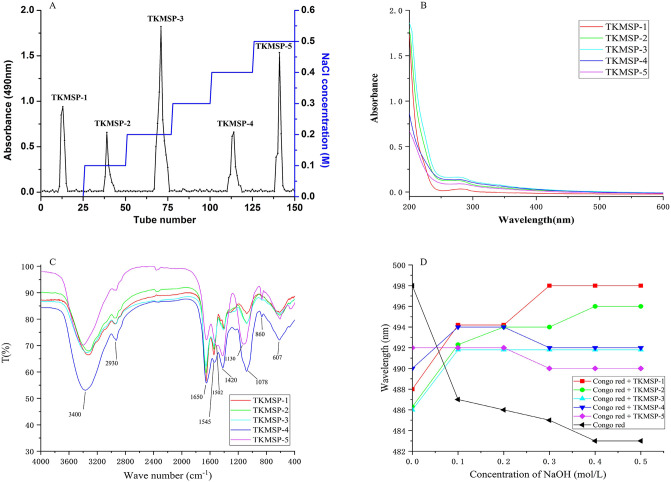

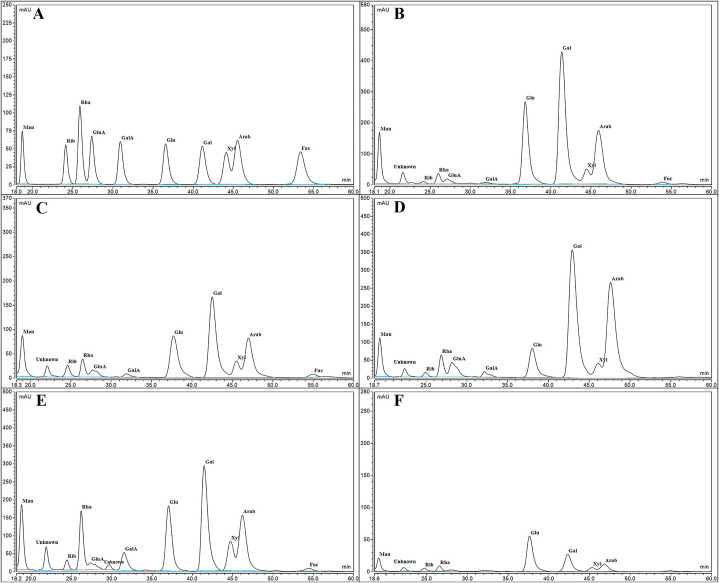

3.7. Monosaccharide compositions and molecular weight analysis of TKMSP

As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 5 , the monosaccharides existing in the five fractions were identified by the standard chromatogram. Although the five polysaccharides contained various monosaccharides, there were differences. TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2 and TKMSP-4 are composed of Mannose (Man), Ribose (Rib), Rhamnose (Rha), Glucuronic acid (GluA), Galacturonic acid (GalA), Glucose (Glu), Galactose (Gal), Xylose (Xyl), Arabinose (Arab) and Fucose (Fuc), but no trace of Fuc was observed in TKMSP-3 and TKMSP-5. Simultaneously, GluA and GalA were also not detected in TKMSP-5. In addition, the decreased order of Man molar ratio in five fractions is as follows: TKMSP-1Man(15.9), TKMSP-3Man(5.09), TKMSP-4Man(4.60), TKMSP-2Man(3.32) and TKMSP-5Man(2.61). The decreased order of GluA molar ratio in five fractions is as follows: TKMSP-3GluA(5.86), TKMSP-1GluA(2.98), TKMSP-4GluA(1.19) and TKMSP-2GluA(1.18). The decreased order of GalA molar ratio in five fractions is as follows: TKMSP-3GalA(2.30), TKMSP-4GalA(2.23), TKMSP-1GalA(1.63) and TKMSP-2GalA(0.68). Generally, the TKMSP-3 exhibited remarkably higher content of the uronic acid compared with that of the other fractions. It is worth noting that no uronic acid was detected in TKMSP-5, which is consistent with the results of FTIR analysis. Significant differences of monosaccharide components in five fractions are achieved. Compared with standard sugars, an unknown monosaccharide in five fractions appeared at the retention time of about 21 min, which needs for further research.

Table 4.

Molar ratio of monosaccharide components of TKMSP.

| Fraction | Man | Rib | Rha | GluA | GalA | Glu | Gal | Xyl | Arab | Fuc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKMSP-1 | 15.9 | 1.00 | 5.07 | 2.98 | 1.63 | 50.63 | 83.14 | 9.16 | 36.02 | 1.86 |

| TKMSP-2 | 3.32 | 1.00 | 1.84 | 1.18 | 0.68 | 7.06 | 11.05 | 2.12 | 5.45 | 0.63 |

| TKMSP-3 | 5.09 | 1.00 | 6.19 | 5.86 | 2.30 | 11.81 | 49.13 | 4.91 | 37.97 | – |

| TKMSP-4 | 4.60 | 1.00 | 6.07 | 1.19 | 2.23 | 8.34 | 12.99 | 3.76 | 7.17 | 0.35 |

| TKMSP-5 | 2.61 | 1.00 | 1.47 | – | – | 13.08 | 6.21 | 1.48 | 2.92 | – |

Fig. 5.

HPLC grams of PMP derivatives of monosaccharide standard samples (A), hydrolysate of TKMSP-1 (B), TKMSP-1 (C), TKMSP-1 (D), TKMSP-1 (E) and TKMSP-5 (F).

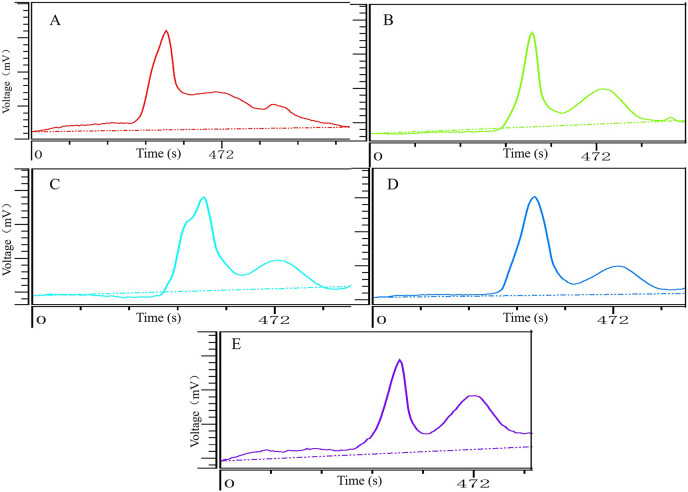

The molecular weight distribution of TKMSP was presented in Table 5 and Fig. 6 . The five fractions show more than two peaks of molecular weight distribution, implying that five fractions were not homogeneous polysaccharides. The highest- molecular-weight peaks of the five fractions are the main peaks (denoted as peak 1), among which TKMSP-4 shows the highest Mw (71.6%, 3.235 × 103 kDa), and TKMSP-2 shows the lowest the Mw (54.0%, 1.132 × 103 kDa). The medium-high-molecular-weight of five fractions were denoted as peak 2, among which the Mw of TKMSP-1 (40.9%, 56.58 kDa) is the highest, and the Mw of TKMSP-2 (46.0%, 34.26 kDa) is the lowest. The Mw of TKMSP-2 was the lowest among the five kinds of fractions. The molecular weight distributions of TKMSP-1 and TKMSP-5 are similar, exhibiting the highest-molecular-weight peak locating at 1.800 × 103 kDa.

Table 5.

Molecular weight distribution of TKMSP.

| Fractions | Peak no. | Retention time (second) | Percentage of area (%) | molecular weight (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKMSP-1 | 1 | 334 | 46.7 | 1.801 × 103 |

| 2 | 458 | 40.9 | 56.58 | |

| 3 | 598 | 12.4 | 0.36 | |

| TKMSP-2 | 1 | 338 | 54.0 | 1.132 × 103 |

| 2 | 486 | 46.0 | 34.26 | |

| TKMSP-3 | 1 | 331 | 69.1 | 2.209 × 103 |

| 2 | 474 | 30.9 | 36.93 | |

| TKMSP-4 | 1 | 318 | 71.6 | 3.235 × 103 |

| 2 | 482 | 28.4 | 41.94 | |

| TKMSP-5 | 1 | 335 | 50.1 | 1.778 × 103 |

| 2 | 462 | 49.9 | 46.71 |

Fig. 6.

Molecular weight distribution diagram of TKMSP-1 (A),TKMSP-1 (B), TKMSP-1 (C), TKMSP-1 (D) and TKMSP-5 (E).

3.8. Analysis of Congo red test

As shown in Fig. 4D, the maximum absorption wavelength of Congo red-polysaccharide varied with the various concentrations of NaOH. Once the concentration of alkali in the mixture of Congo red polysaccharide increased gradually, λmax of polysaccharide with triple helix structure changed from red shift and blue shift sequentially [43]. It can be noted that the max of Congo red+TKMSP-1, Congo red+TKMSP-2, Congo red+TKMSP-3 and Congo red+TKMSP-4 underwent a large red shift first and then a weak blue shift or stabilization, indicating a helix-coil transition under the treatment of alkali. However, when the concentration of NaOH increased from 0 mol/L to 0.5 mol/L, the λmax of Congo red + TKMSP-5 complex showed a similar trend of no red shift as Congo red alone. Therefore, it can be concluded that TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2, TKMSP-3 and TKMSP-4 possessed the triple helical conformation, while triple helix of TKMSP-5 are not obvious.

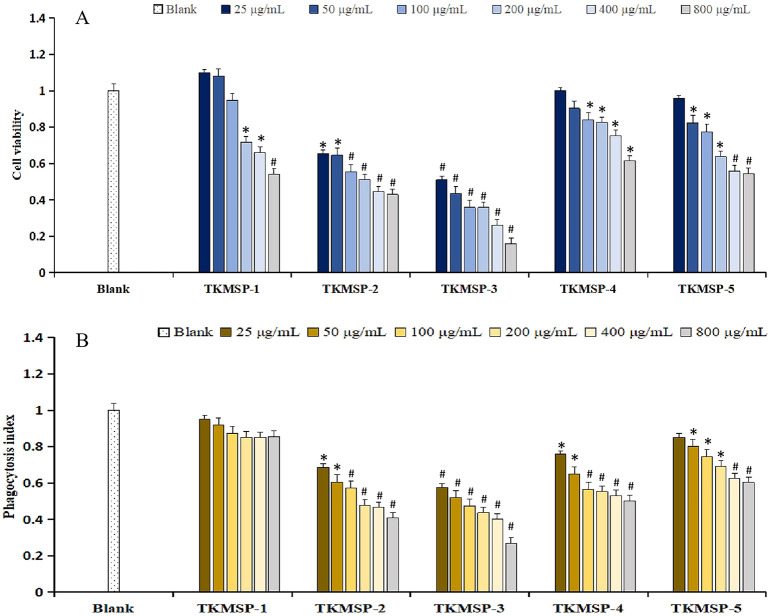

3.9. Immunomodulatory activity

Macrophages play a crucial role in both innate and adaptive immune responses, while the abnormal proliferation of macrophages can result in the diseases related to peripheral inflammation [44]. To investigate the toxicity of TKMSP on the RAW264.7 cells, MTT assays were conducted to examine cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 7A, all five fractions showed inhibitory effect on the proliferation of RAW264.7 cells. Although the cell viability was higher than that of the blank control when the concentration of TKMSP-1 was 25 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL respectively, there was no significant difference observed. Compared with blank control, the five fractions at the concentration of 25–800 μg/mL decreased the viability of macrophages dramatically in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.05), and the inhibition effect of TKMSP-3 was extremely significant (P < 0.01). The IC50 values of TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2, TKMSP-3, TKMSP-4 and TKMSP-5 on the RAW264.7 cells were 721.97 ± 5.12, 240.28 ± 3.60, 30.05 ± 1.54, 1431.39 ± 6.81 and 709.12 ± 4.57 μg/mL, respectively, suggesting that all five polysaccharides exhibited a potential of immunosuppressive activity, and that the inhibition rate of TKMSP-3 was significantly higher than compared to the other four fractions.

Fig. 7.

Cell viability (A) and phagocytosis index (B) of five components; #P < 0.01 vs Blank control; *P < 0.05 vs Blank control.

Analysis of the phagocytosis capacity of activated macrophages can reflect the effects of examined sample on immune function [45]. As shown in Fig. 7B, the phagocytosis indices for TKMSP at the treated concentration ranging from 25 μg/mL to 800 μg/mL were all lower than 1.0, indicating that all of the five fractions have the ability to inhibit the phagocytosis of 264.7 cells. It is noteworthy that the phagocytic activity of RAW264.7 cells was inhibited by the five fractions with an increased sample concentration, and the effect of inhibition was dose-dependent. The difference was extremely significant (P < 0.01) compared with the blank control group, which was consistent with the results of MTT examination.

In generally, the immune function of RAW264.7 cells can be enhanced by natural polysaccharide within a certain concentration range [46]. The cytotoxicity effect of polysaccharides has been reported in other literatures, but the mechanism of its toxic effect (i.e. the inhibition of proliferation) is still unclear [[47], [48], [49]]. The inhibition of polysaccharides to macrophage should not be ignored, which might be the crucial point for the development of immunosuppressants. The regulation of polysaccharide on the immune function of macrophages is a very complicated system, and there are various influencing factors for the activity related to polysaccharide immune regulation, especially their chain conformations, monosaccharide composition, molecular weight and content of uronic acid [50]. In previous researches, it has been indicated that the significant differences in the structural characterization of the five fractions is mainly responsible for their different biological activities. It has been reported that immune cells have a variety of carbohydrate recognition domains, such as mannose receptors, macrophage galactose-type lectin and dendritic cells, which can specifically recognize rich mannose, galactose and β-glucan, respectively [[51], [52], [53]]. The five fractions are common in containing Gal, Man and Glu monosaccharide components of high concentrations, which can significantly influence the expression of macrophages and even their production. Meanwhile, uronic acid and triple helix conformation is considered to be one of the main sources of polysaccharide bioactivity [54,55], while the lack of GluA, GalA and helical structure in TKMSP-5 results in the weak inhibitory activity. In addition, TKMSP-1 and TKMSP-5 are similar weak inhibition on macrophage proliferation due to their similar Mw (about 50 kDa and 1.800 × 103 kDa). The molecular weight of TKMSP-2, TKMSP-3 and TKMSP-4 are quite different, and their biological activities are significantly different. It has been reported that the glycogen with a high molecular weight (more than 10 kDa) can hardly promote the proliferation of RAW264.7 cells [56]. The major molecular weight segments of the five fractions in this study were all more than 10 kDa, which may be one of the reasons failing to stimulate macrophage proliferation, even had inhibitory effect. Due to the interaction of various structural characterization information of polysaccharide, it shows unique biological activity. As a result, the structure-activity relationship and the mechanism of action of polysaccharides can be clarified clearly if more detailed structural information of polysaccharides is available, which requires a further study.

4. Conclusion

In this study, a central composite design combined with RSM was used to optimize the microwave extraction conditions of crude polysaccharide from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim seeds (liquid-solid ratio 42 mL/g, extraction temperature 80 °C, microwave power 570 W, extraction time 26 min), in order to obtain the best polysaccharide yield. The five polysaccharide fractions (TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2, TKMSP-3, TKMSP-4 and TKMSP-5) were successfully isolated by DEAE-52 column. The analysis of structural characterization indicated that five fractions had characteristic absorption peak, abundant monosaccharide composition, and all of them being polydisperse heterpolysaccharides. However, there were significant differences among the five fractions. Especially, TKMSP-1, TKMSP-2 and TKMSP-4 were both composed of Man, Rib, Rha, GluA, GalA, Glu, Gal, Xyl, Arab and Fuc. However, there was no Fuc in TKMSP-3, while TKMSP-5 lacked GluA, GalA, and Fuc. Furthermore, TKMSP-3 had the strongest inhibitory effects on the RAW264.7 cells, suggesting that TKMSP-3 has the potential to be novel immunosuppressants to be applied in pharmaceuticals. In the future research, it needs to be separated according to different molecular weight, and characterized by NMR, GC–MS and SEM, so as to better clarify the structure-activity relationship and mechanism of immunosuppression.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhengyu Hu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft.

Hongli Zhou: Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing.

JingLi Zhao: Resources, Data curation.

JiaQi Sun: Visualization.

Mei Li: Supervision, Investigation.

Xinshun Sun: Validation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (Grant No. 2019C045-4), and the Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (Grant No. 20190304102YY).

References

- 1.Clark D.N., Markham J.L., Sloan C.S., Poole B.D. Cytokine inhibition as a strategy for treating systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Immunol. 2013;148(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu P.W., Wang J., Wen W., Ting P., Chen H., Fu Y., Wang F.S., Huang J.H., Xu S.J. Cinnamaldehyde suppresses NLRP3 derived IL-1β via activating succinate/HIF-1 in rheumatoid arthritis rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M., Li X., Xia J., Chen N., Xiang J., Yu T., Bai T., Xie X., Zhang L., Li C., Yuan Y., Chen H., Li H., Huang H., Tu S., Gong F., Liu Y., Wei Y., Dong C., Zhou F., Gu X., Xu J., Liu Z., Zhang Y., Li H., Shang L., Wang K., Li K., Zhou X., Dong X., Qu Z., Lu S., Hu X., Ruan S., Luo S., Wu J., Peng L., Cheng F., Pan L., Zou J., Jia C., Wang J., Liu X., Wang S., Wu X., Ge Q., He J., Zhan H., Qiu F., Guo L., Huang C., Jaki T., Hayden F.G., Horby P.W., Zhang D., Wang C. A trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(19):1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGonagle D., Sharif K., O’Regan Anthony., Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020;19(6) doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J., Farmer J.D., Jr., Lane W.S., Friedman J., Weissman I., Schreiber S.L. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66(4):807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X.S., Workeneh B., Hu Z.Y., Li R.S. Effect of immunosuppression on the human mesangial cell cycle. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11(2):910. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang Z.R., Li D.W., Peng S.M. Effects of seed extracts from Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim on antifeeding and growth and development of Pieris rapae L. New Biotechnol. 2009;25:S251. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.06.559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W.F., Wang L.Z., Jiang J.X. Fatty acid profile of Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim. seed oil. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 2009;63(4):489–492. doi: 10.2478/s11696-009-0032-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman A.A., Moon S.S. Isoetin 5′-methyl ether, a cytotoxic flavone from Trichosanthes kirilowii. B. Korean Chem. Soc. 2007;28(8):1261–1264. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2007.28.8.1261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon S.S., Rahman A.A., Kim J.Y., Kee S.H. Hanultarin, a cytotoxic lignan as an inhibitor of actin cytoskeleton polymerization from the seeds of Trichosanthes kirilowii. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16(15):7264–7269. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shu S.H., Xie G.Z., Guo X.L., Wang M. Purification and characterization of a novel ribosome-inactivating protein from seeds of Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim. Protein Expr. Purif. 2009;67(2):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiong X., Huang G.L., Huang H.L. The antioxidant activities of phosphorylated polysaccharide from native ginseng. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;126:842–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu M.M., Zeng P., Li X.T., Shi L.G. Antitumor and immunomodulation activities of polysaccharide from Phellinus baumii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;91:1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbou A., Kadri N., Debbache N., Dairi S., Remini H., Dahmoune F., Berkani F., Adel K., Belbahi A., Madani K. Effect of precipitation solvent on some biological activities of polysaccharides from Pinus halepensis Mill. seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;141:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng Y.J., Huang L.X., Zhang C.H., Xie P.J., Cheng J., Wang X., Liu L.J. Novel polysaccharide from Chaenomeles speciosa seeds: structural characterization, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity evaluation. Int. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;153:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z., Li H., Wang Y.D., Yang D.J., Tan H.J., Zhan Y., Yang Y., Luo Y., Chen G. Optimization extraction, structural features and antitumor activity of polysaccharides from Z. jujuba cv. Ruoqiangzao seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;135:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maran J. Prakash, Swathi K., Jeevitha P., Jayalakshmi J., Ashvini G. Microwave-assisted extraction of pectic polysaccharide from waste mango peel. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;123:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sodeifian G., Sajadian S.A., Ardestani N.S. Extraction of Dracocephalum kotschyi Boiss using supercritical carbon dioxide: experimental and optimization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2016;107:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2015.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devi V., Khanam S.B. Study of ω-6 linoleic and ω-3 α-linolenic acids of hemp (Cannabis sativa) seed oil extracted by supercritical CO2 extraction: CCD optimization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019;7(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2018.102818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C., Zhang B., Huang Q., Fu X., Liu R.H. Microwave-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Moringa oleifera lam. leaves: characterization and hypoglycemic activity. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2007;100:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.01.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuko T., Minami A., Iwasaki N., Majima T., Nishimura S., Lee Y.C. Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol-sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 2005;339(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z., Li H., Tu D.W., Yang Y., Zhan Y. Extraction optimization, preliminary characterization, and in vitro antioxidant activities of crude polysaccharides from finger citron. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013;44:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenkrantz N., Asboe-Hansen G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Biochem. 1973;54(2):484. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sevag M.G., Lackman D.B., Smolens J. The isolation of components of streptococcal nucleoproteins in serologically active form. J. Biol. Chem. 1938;124(1):42–49. doi: 10.1029/97PA02893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai J., Wu Y., Chen S.W., Zhu S., Yin H.P., Wang M., Tang J. Sugar compositional determination of polysaccharides from Dunaliella salina by modified rp-hplc method of precolumn derivatization with 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;82(3):629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.05.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Z.Y., Wang P.H., Zhou H.L., Li Y.P. Extraction, characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Carex meyeriana Kunth using different methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;120(Pt B):2155–2164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie C., Zhu P., Wang M., Ma S., Wei Z. Optimization of water-soluble polysaccharides from stem lettuce by response surface methodology and study on its characterization and bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;95:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi M., Yang Y., Hu X., Zhang Z. Effect of ultrasonic extraction conditions on antioxidative and immunomodulatory activities of a Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide originated from fermented soybean curd residue. Food Chem. 2014;155(10):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv X., Chen D., Yang L., Zhu N., Li J., Zhao J., Hu Z.B., Wang F.J., Zhang L.W. Comparative studies on the immunoregulatory effects of three polysaccharides using high content imaging system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;86(1):28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N.S., Yan C.Y., Hua D.H., Zhang D.Z. Isolation, purification, and structural characterization of a novel polysaccharide from Ganoderma capense. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013;57:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Z.Y., Zhang Q., Li Y.F., Dong L.L., Liu S.L. Optimization of ultrasound extraction of Alisma orientalis polysaccharides by response surface methodology and their antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;119:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourtoom T., Chinnan M.S., Jantawat P., Sanguandeekul R. Recovery and characterization of proteins precipitated from surimi wash-water. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009;42(2):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prakash Maran J., Sivakumar V., Thirugnanasambandham K., Sridhar R. Optimization of microwave assisted extraction of pectin from orange peel. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;97(2):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su S.N., Nie H.L., Zhu L.M., Chen T.X. Optimization of adsorption conditions of papain on dye affinity membrane using response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol. 2009;100(8):2336–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin L., Guan X., Liu W., Zhang X., Yan W., Yao W.B., Gao X.D. Characterization and antioxidant activity of a polysaccharide extracted from Sarcandra glabra. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;90(1):524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hua D.H., Zhang D.Z., Huang B., Yi P., Yan C.Y. Structural characterization and DPPH· radical scavenging activity of a polysaccharide from Guara fruits. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;103:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu X.H., Liu Y., Wu X.L., Liu L.Z., Fu W., Song D.D. Isolation, purification, characterization and immunostimulatory activity of polysaccharides derived from American ginseng. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;156:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu D., Sun Q.W., Xu J., Li N., Lin J.A., Chen S., Li F. Purification, characterization, and bioactivities of a polysaccharide from mycelial fermentation of Bjerkandera fumosa. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;167:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y., Li Q., Mao G., Zou Y., Feng W., Zheng D., Wang W., Zhou L.L., Zhang T.X., Yang J., Yang L.Q., Wu X.Y. Optimization of enzyme-assisted extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;101(1):606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X., Huang M., Qin C., Lv B., Mao Q., Liu Z. Structural characterization and evaluation of the antioxidant activities of polysaccharides extracted from Qingzhuan brick tea. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;101:768. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu X.Q., Li J., Hu Y. Polysaccharides from Inonotus obliquus sclerotia and cultured mycelia stimulate cytokine production of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro and their chemical characterization. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014;21(2):269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M.C., Zhu P.L., Zhao S.W., Nie C.Z.P., Wang N.F., Du X.F., Zhou Y.B. Characterization, antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the swollen culms of Zizania latifolia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;95:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun H.X., Zhang J., Chen F.Y., Chen X.F., Zhou Z.H., Wang H. Activation of RAW264.7 macrophages by the polysaccharide from the roots of Actinidia eriantha and its molecular mechanisms. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;121:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alan A. Phagocytosis and the inflammatory response. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(2):340–345. doi: 10.1086/374747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong Q.P., Hao H.R., He L., Jing Y., Xu T.T., Chen J., Zhang H.J., Hu T., Zhang Q.H., Yang X., Yuan J., Huang Y. Anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic activities of a purified polysaccharide from flesh of Cipangopaludina chinensis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;176:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu Z.Y., Zhou H.L., Li Y.P., Wu M.F., Yu M., Sun X.S. Optimized purification process of polysaccharides from Carex meyeriana Kunth by macroporous resin, its characterization and immunomodulatory activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;132:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao J.W., Zheng C.Y., Wei H., Wang D.W., Zhu W. Proapoptic and immunotoxic effects of sulfur-fumigated polysaccharides from Smilax glabra Roxb. in RAW264.7 cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018;292:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meng L.Z., Feng K., Wang L.Y., Cheong K.L., Nie H., Zhao J., Li S.P. Activation of mouse macrophages and dendritic cells induced by polysaccharides from a novel Cordyceps sinensis fungus UM01. J. Funct. Foods. 2014;9:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hou C.Y., Chen L.L., Yang L.Z., Ji X.L. An insight into anti-inflammatory effects of natural polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;153:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X.R., Qi C.H., Guo Y., Zhou W.X., Zhang Y.X. Toll-like receptor 4-related immunostimulatory polysaccharides: primary structure, activity relationships, and possible interaction models. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;149:186–206. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanjeewa K.K. Asanka, Fernando I.P.S., Kim S.Y., Kim H.S., Ahn G., Jee Youngheun, Jeon Y.J. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activities of high molecular weight sulfated polysaccharide; containing fucose separated from Sargassum horneri: short communication. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;107(Pt A):803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu Y., Shen M., Wang Z., Wang Y., Xie M., Xie J. Sulfated polysaccharide from Cyclocarya paliurus enhances the immunomodulatory activity of macrophages. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;174(1):669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miura N.N., Ohno N., Adachi Y., Aketagawa J., Tamura H., Tanaka S., Tadomae T. Comparison of the blood clearance of triple- and single-helical schizophyllan in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1995;18(1):185–189. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kakutani R., Adachi Y., Kajiura H., Takata H., Kuriki T., Ohno N. Relationship between structure and immunostimulating activity of enzymatically synthesized glycogen. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342(16):2371–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]