Abstract

Background

There is inconclusive and controversial evidence of the association between allergic diseases and the risk of adverse clinical outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Objective

We sought to determine the association of allergic disorders with the likelihood of a positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) test result and with clinical outcomes of COVID-19 (admission to intensive care unit, administration of invasive ventilation, and death).

Methods

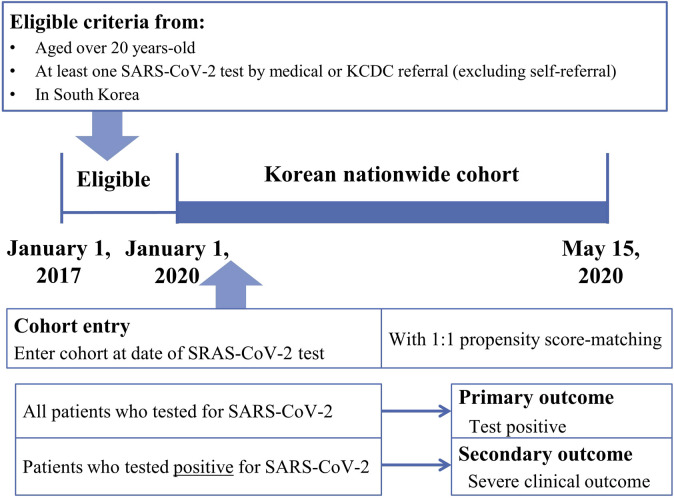

A propensity-score–matched nationwide cohort study was performed in South Korea. Data obtained from the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea from all adult patients (age, >20 years) who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 in South Korea between January 1, 2020, and May 15, 2020, were analyzed. The association of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and allergic diseases in the entire cohort (n = 219,959) and the difference in clinical outcomes of COVID-19 were evaluated in patients with allergic diseases and SARS-CoV-2 positivity (n = 7,340).

Results

In the entire cohort, patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing were evaluated to ascertain whether asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with an increased likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity. After propensity score matching, we found that asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with SARS-CoV-2 test positivity. Patients with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 than patients with allergic asthma.

Conclusions

In a Korean nationwide cohort, allergic rhinitis and asthma, especially nonallergic asthma, confers a greater risk of susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Key words: COVID-19, asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis

Abbreviations used: aOR, Adjusted odds ratio; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ICD-10, International Classification of Disease, Tenth revision; ICU, Intensive care unit; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SMD, Standardized mean difference

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and has resulted in a rapidly spreading pandemic.1 , 2 According to the World Health Organization reports issued in mid-May 2020, approximately 4 million COVID-19 cases have been officially confirmed, and more than a quarter of a million people have died.3 With the rapid increase in the number of patients with COVID-19, the clinical progress, epidemiological facts, and prognosis of these patients continue to be swiftly revealed, and this could facilitate improved hospitalized management as well as prevention of COVID-19.4 The spectrum of COVID-19 outcomes is related to underlying diseases or conditions that may potentially modify immunity, thereby aggravating the disease course.5 For example, higher age (>65 years),1 , 4 preexisting pulmonary disease,5 , 6 chronic kidney disease,7 diabetes mellitus,6 hypertension,5 cardiovascular disease,8 obesity (body mass index > 30),9 malignancy,10 smoking,11 and presumably immunocompromised status (eg, the use of anti-inflammatory biologics,12 transplantation,12 and chronic HIV infection)13 are known to be possible epidemiologic risk factors for severe COVID-19.

Chronic allergic disease is associated with the tissue remodeling process, and persistent inflammation may weaken the patient’s immune system to induce susceptibility to infection14; however, the association between allergic disease and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 has not been demonstrated and remains debatable (no association15 , 16 or positive association17 , 18). In previous studies, asthma in patients with COVID-19 was found to be associated with severe clinical outcomes in analyses based on data from the UK Biobank17 and Seattle,18 but was not associated with severe clinical outcomes in Wuhan.15 , 16 Asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis contribute to the exacerbation of illnesses caused by common respiratory viruses,19 with an increased risk of cutaneous and upper airway infections.20 Moreover, impaired innate immunity, induced by the depletion of type 1 IFN, readily facilitates the spread of viruses or other pathogens.21 However, Kimura et al22 recently found that type 2 inflammatory cytokines, including IL-13, significantly modulate the expression of molecules that mediate SARS-CoV-2 host cell entry in asthma and atopic airway epithelial cells to induce angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 decrease and increase TMPRSS2 expression.22 This implies a complex biological mechanism wherein an underlying asthmatic and atopic disease can affect the susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and pathogenesis of COVID-19, increasing the necessity for evidence of its clinical relevance. Therefore, the likelihood of a SARS-CoV-2 infection positivity rate and the severity of COVID-19 outcomes mediated by underlying allergic morbidities need to be determined.

We hypothesized that allergic comorbidity is associated with an increased likelihood of the risk of or clinical outcomes of COVID-19 (ie, death, admission to the intensive care unit [ICU], invasive ventilation, and length of hospital stay). This study aimed to ascertain an association of risk factors and COVID-19 illness severity, with a goal to improve the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic allergic diseases. In a Korean nationally representative cohort of 219,959 participants who tested for SARS-CoV-2 in South Korea, we investigated the potential association of allergic disorders with the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity. Furthermore, we examined the differences in COVID-19 clinical outcomes by allergic diseases among 7340 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

Data source

Data were obtained from a Korean national health insurance claims-based database. The government of the Republic of Korea decided to share the world’s first deidentified COVID-19 nationwide patient data with domestic and international researchers. This large-scale cohort comprised all individuals who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing in South Korea through services facilitated by the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Korean government provided mandatory and free health insurance for all Korean patients with COVID-19.23 , 24 Therefore, the data set analyzed in this study includes the records of personal data, health care records of inpatients and outpatients from the past 3 years (including health care visits, prescriptions, diagnoses, and procedures), pharmaceutical visits, COVID-19–related outcomes, and death records. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sejong University (SJU-HR-E-2020-003). All patient-related records used in our study were anonymized to ensure confidentiality.

Study population

We identified all individuals older than 20 years who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing in South Korea between January 1, 2020, and May 15, 2020, by medical or Korea Centers for Disease Control referral (excluding self-referral). The laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as a positive result on a real-time RT-PCR assay of nasal or pharyngeal swabs, in accordance with the World Health Organization guideline.1 For each identified individual who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing, the cohort entry data (individual index data) were the date of the first SARS-CoV-2 test. We combined the claims-based data from the national health insurance service between January 1, 2015, and May 15, 2020, and extracted information on age, sex, and region of residence from the insurance eligibility data. A history of diabetes mellitus (E10-14), ischemic heart disease (I20-25), cerebrovascular disease (I60-64, I69, and G45), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; J43-J44, except J430), hypertension (I10-13 and I15), and chronic kidney disease (N18-19) was confirmed by the reporting of at least 2 claims within 1 year during this 3-year study period using the appropriate International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code.25 The Charlson comorbidity index score was calculated from the ICD-10 codes by methods that were reported previously.26 The use of systemic glucocorticoids within 180 days preceding cohort entry was also investigated and recorded.27 The region of residence was classified as rural (ie, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Gyeongsangbuk, Gyeongsangnam, Chungcheongbuk, Chungcheongnam, Jeollabuk, Jeollanam, and Jeju) or urban (eg, Seoul, Sejong, Busan, Incheon, Daegu, Gwangju, Daejeon, and Ulsan).28 , 29 The final analysis data set comprised data from 219,959 individuals who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing, and included 7,340 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Exposure

Asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis were defined using the ICD-10 code (asthma, J45 or J46; allergic rhinitis, J30.1, J30.2, J30.3, or J30.4; atopic dermatitis, L20) with at least 2 claims within 1 year during this 3-year study period.25 , 30 The current allergic status was defined by the assignment of 2 or more claims using the appropriate ICD-10 code from January 1, 2019, to May 20, 2020. Allergic asthma was defined as asthma with at least 1 additional allergic disorder (allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis), whereas nonallergic asthma was defined as asthma without any atopic disorder.26

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was a positive laboratory test result among all individuals who were tested for SARS-CoV-2. The secondary outcome was the length of hospital stay and the severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19,5 , 31 which comprised ICU admission, administration of invasive ventilation, or death, of patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Analysis overview

In this nationwide cohort study, the “exposure” comprised the development of allergic diseases; the “primary end point” was the positive laboratory test results for SARS-CoV-2 among all the individuals who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing, and the “secondary end point” was the clinical outcome of patients with COVID-19 who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

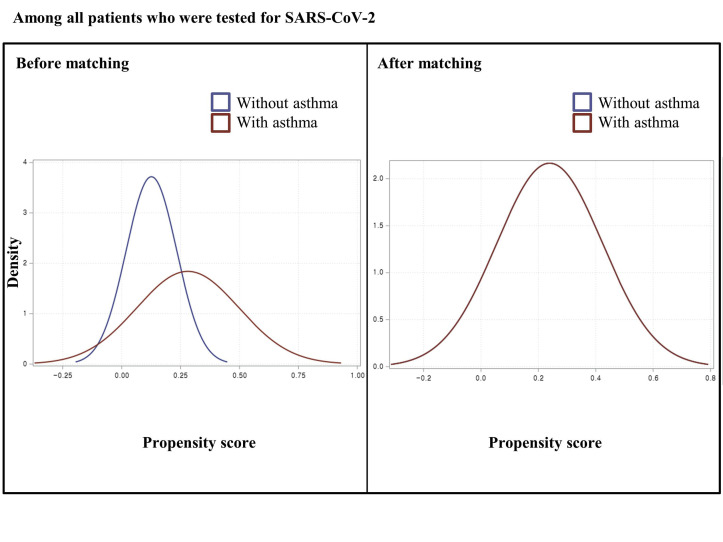

Propensity score matching was performed to balance the baseline covariates of the 2 groups and to decrease the potential confounding factors from the predicted probability of (1) individuals with asthma versus individuals without asthma among all patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing (n = 219,959); (2) individuals with allergic rhinitis versus individuals without allergic rhinitis among all patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing; (3) individuals with atopic dermatitis versus individuals without atopic dermatitis among all patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing; (4) individuals with asthma versus individuals without asthma among patients with confirmed COVID-19 (n = 7340); (5) individuals with allergic rhinitis versus individuals without allergic rhinitis asthma among patients with confirmed COVID-19; and (6) individuals with atopic dermatitis versus individuals without atopic dermatitis among patients with confirmed COVID-19. Furthermore, we performed 6 additional propensity score matching sets based on the current allergic status.

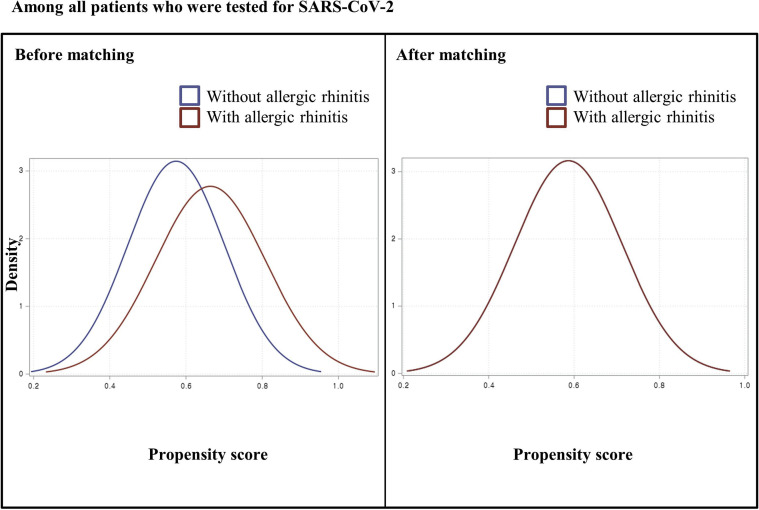

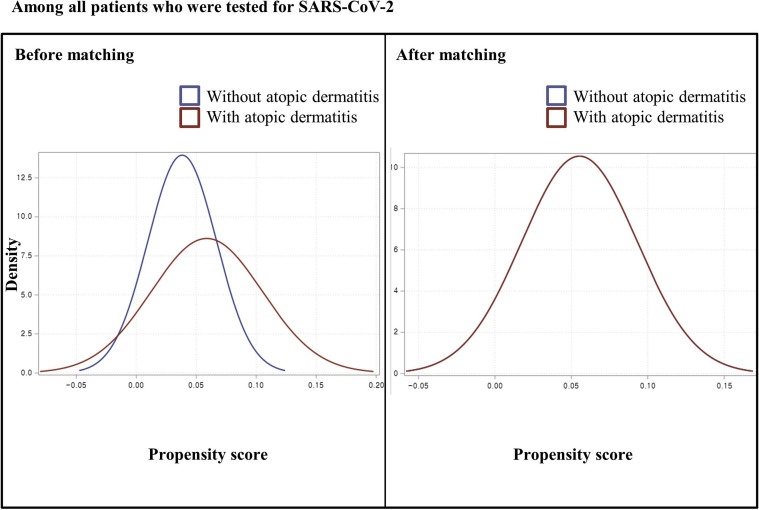

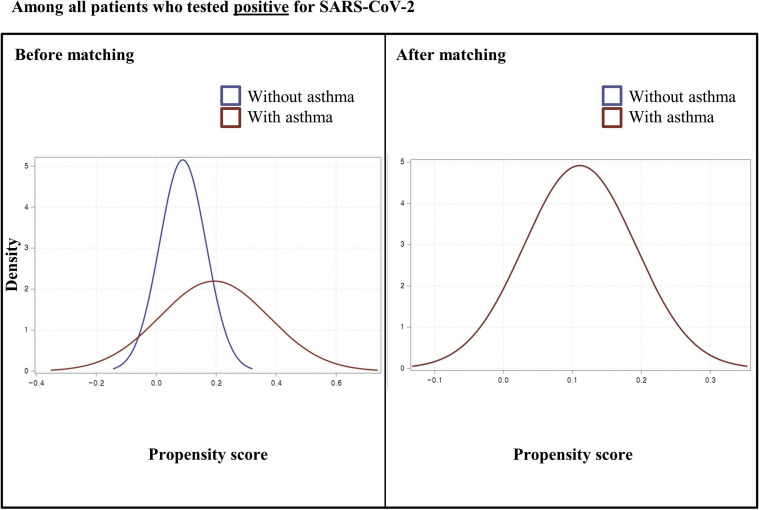

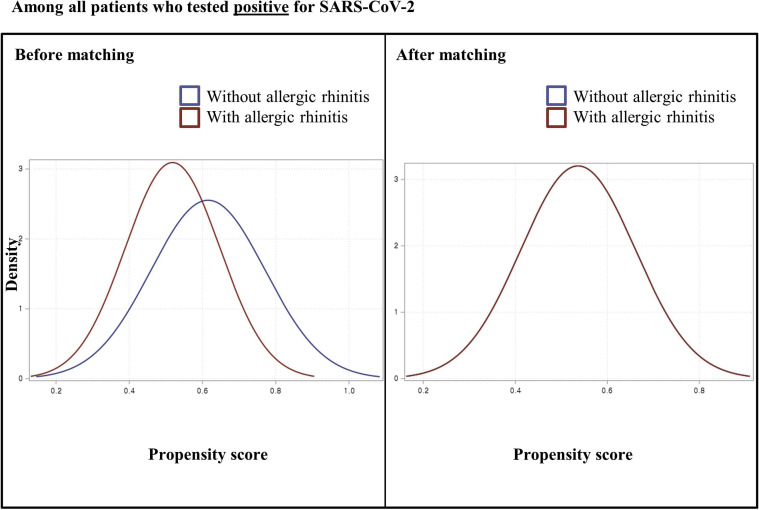

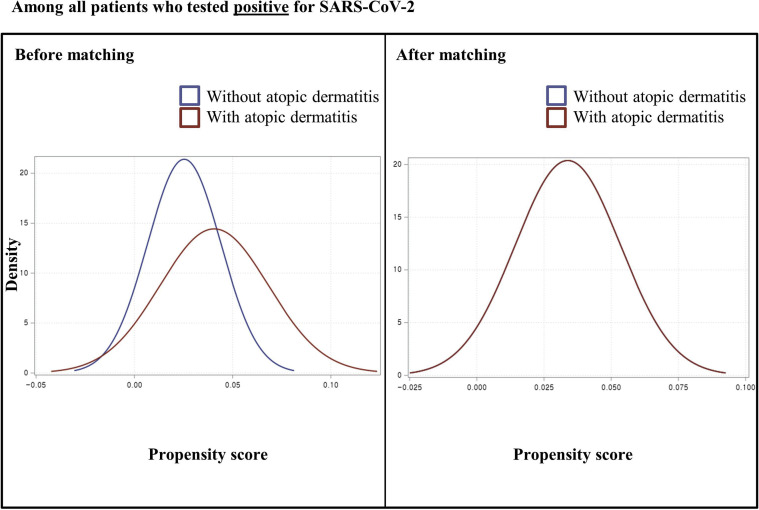

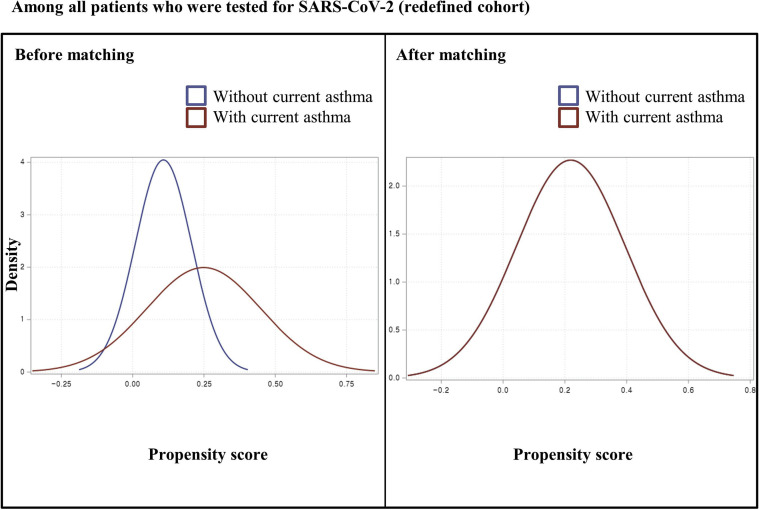

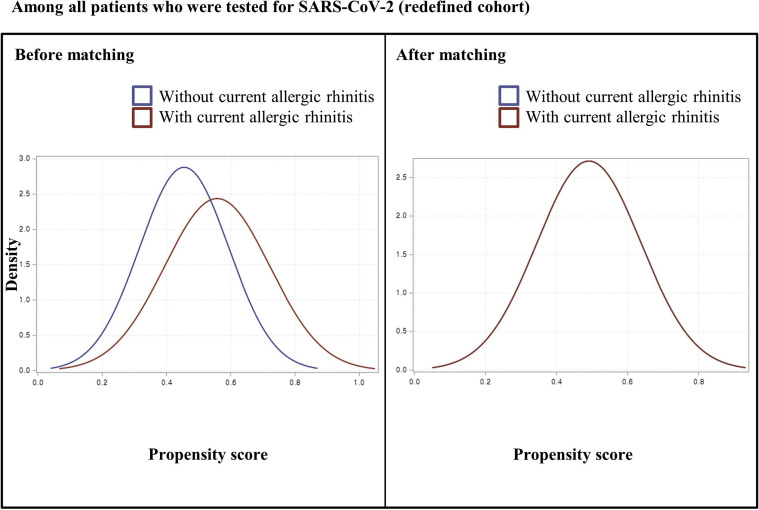

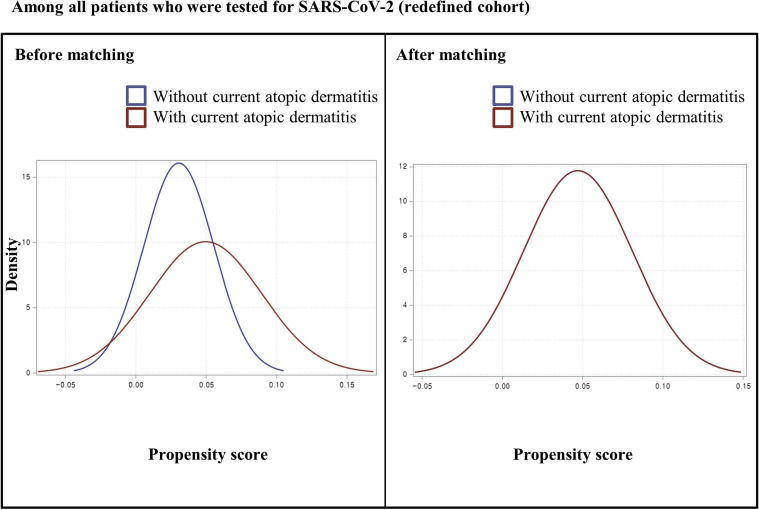

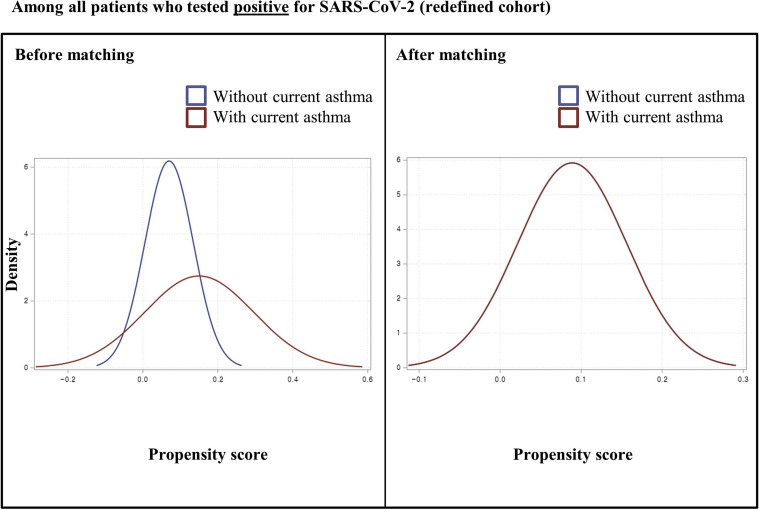

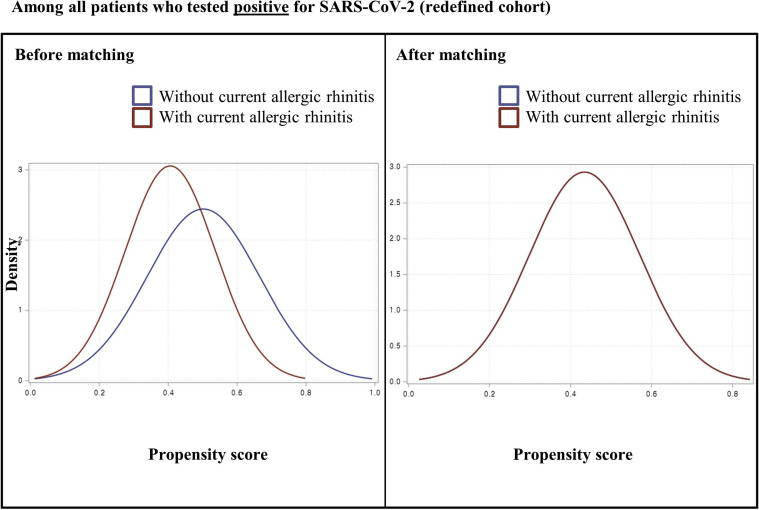

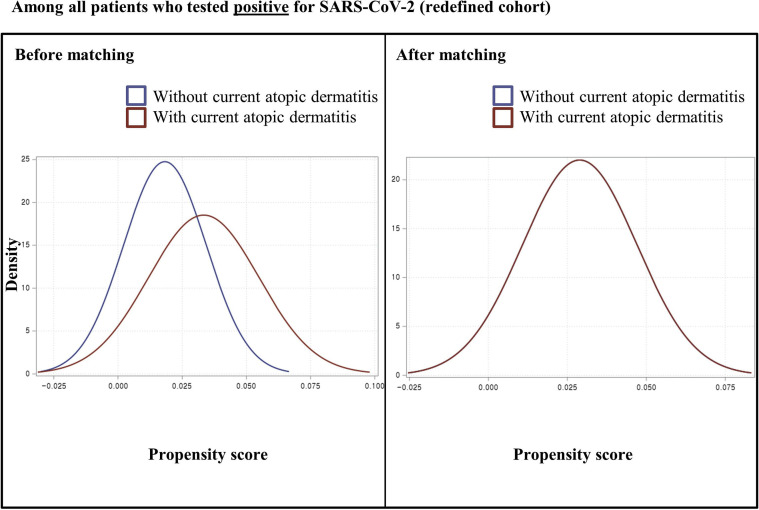

Each matching was undertaken in a 1:1 ratio using a “greedy nearest-neighbor” algorithm among all individuals who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing and among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection.32 We used a logistic regression model adjusted for age; sex; region of residence; history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, or chronic kidney disease; the Charlson comorbidity index; and use of immunosuppressants. The adequacy of matching was confirmed by comparing propensity score densities (see Figs E1-E12 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) and standardized mean differences (SMD).26

Data were analyzed by using binary logistic regression or analysis of covariance models. The estimation of the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs or the adjusted mean difference (with 95% CIs) was performed after adjusting for the following potential confounders to reduce the possibility of bias: age; sex; region of residence (urban or rural); history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease; the Charlson comorbidity index (0, 1, and ≥2); previous use of systemic glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants; and allergic disorders (as relevant). Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

A primary analysis (a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19) using binary logistic regression, a secondary analysis (a severe clinical outcome of COVID-19) using binary logistic regression, and another secondary analysis (length of hospital stay) using analysis of covariance were conducted on the basis of presence of allergic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis). In addition, the following several analyses were undertaken: (1) we repeated the main analysis of the asthma phenotype (none vs allergic asthma vs nonallergic asthma), and (2) we redefined the cohort by using a stricter definition of “current allergic status.”

Patient and public involvement

No patients were directly involved in designing the research question or in conducting the research. No patients were asked for advice on interpretation or writing up of the results. There are no plans to involve patients or the relevant patient community in the dissemination of study findings at this time.

Results

Descriptive overview

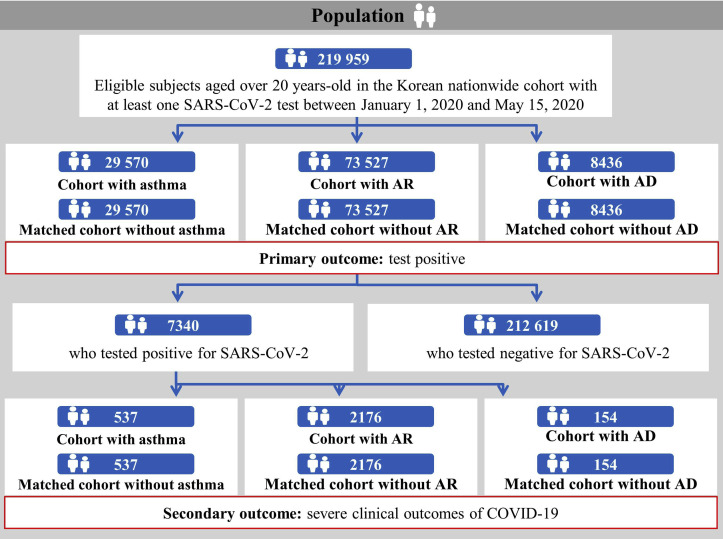

The demographic and clinical characteristics of a total of 219,959 patients (mean age ± SD, 49.0 ± 19.9 years; male [%], 104,331 [47.4%]) who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing (Table I and Figs 1 and 2 ) were analyzed. In this study population, 32,845 patients (14.9%) were diagnosed with asthma, 138,743 patients (63.1%) with allergic rhinitis, and 8,591 (3.9%) with atopic dermatitis. Among the 7340 patients (mean age ± SD, 47.1 ± 19.0 years; male [%], 2970 [40.5%]) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, there were 725 (9.9%), 4210 (57.4%), and 136 (1.9%) patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, respectively.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 in a Korean nationwide cohort

| Baseline characteristic | Entire cohort | Entire cohort |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 | Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 | SMD | ||

| Total, n (%) | 219,959 | 212,619 (96.7) | 7340 (3.3) | |

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 49.0 ± 19.9 | 49.5 ± 19.9 | 47.1 ± 19.0 | 0.124 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 104,331 (47.4) | 101,361 (47.7) | 2,970 (40.5) | |

| Female | 115,628 (52.6) | 111,258 (52.3) | 4,370 (59.5) | |

| Region of residence, n (%) | 0.091 | |||

| Rural | 96,315 (43.8) | 92,780 (43.6) | 3,535 (48.2) | |

| Urban | 123,644 (56.2) | 119,839 (56.4) | 3,805 (51.8) | |

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 38,396 (17.5) | 37,445 (17.6) | 951 (13) | 0.130 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 32,864 (14.9) | 32,359 (15.2) | 505 (6.9) | 0.268 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 22,134 (10.1) | 21,676 (10.2) | 458 (6.2) | 0.144 |

| History of COPD, n (%) | 18,636 (8.5) | 18,286 (8.6) | 350 (4.8) | 0.154 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 66,281 (30.1) | 64,643 (30.4) | 1,638 (22.3) | 0.184 |

| History of chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 15,360 (7.0) | 15,106 (7.1) | 254 (3.5) | 0.163 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | 0.356 | |||

| 0 | 120,433 (54.8) | 115,531 (54.3) | 4,902 (66.8) | |

| 1 | 25,938 (11.8) | 25,129 (11.8) | 809 (11.0) | |

| ≥2 | 73,588 (33.5) | 71,959 (33.9) | 1,629 (22.2) | |

| Previous use of immunosuppressants, n (%) | 3,922 (1.8) | 3,873 (1.8) | 49 (0.7) | 0.104 |

| Exposure | ||||

| Previous use of systemic glucocorticoids, n (%) | 80,943 (36.8) | 78,889 (37.1) | 2,054 (28) | |

| Asthma, n (%) | 32,845 (14.9) | 32,120 (15.1) | 725 (9.9) | |

| Current asthma, n (%) | 27,638 (12.6) | 27,080 (12.7) | 558 (7.6) | |

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 138,743 (63.1) | 134,533 (63.3) | 4,210 (57.4) | |

| Current allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 111,530 (50.7) | 108,234 (51.0) | 3,296 (44.9) | |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 8,591 (3.9) | 8,402 (4.0) | 189 (2.6) | |

| Current atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 6,840 (3.1) | 6,704 (3.2) | 136 (1.9) | |

An SMD of <0.1 indicates no major imbalance.

Fig 1.

Flowchart depicting the study enrollment. KCDC, Korea Centers for Disease Control.

Fig 2.

Disposition of patients in the Korean nationwide cohort. AD, Atopic dermatitis; AR, allergic rhinitis.

SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and allergic diseases

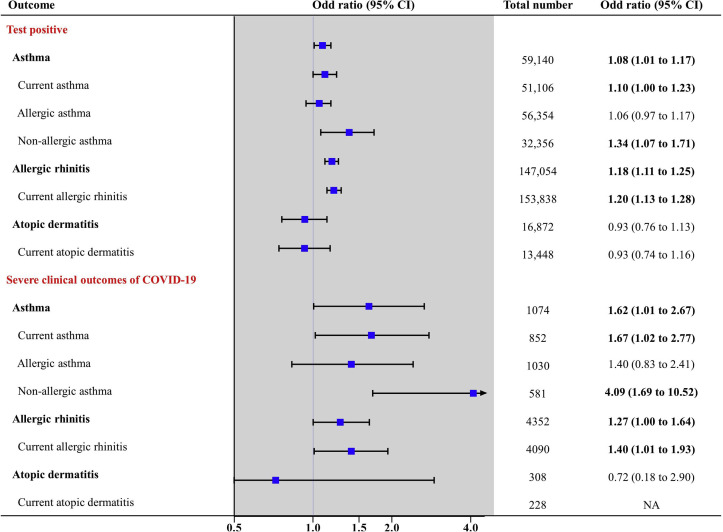

After propensity score matching among patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 219,959), there were no major imbalances in the baseline covariates evaluated by SMD between both groups (Table II ; all SMDs < 0.1). Table II describes the ORs for the association of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity with allergic diseases among all patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2. Among all the patients tested, the SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate was 2.3% in patients with asthma, compared with 2.2% in those without asthma (aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.17) and 3.3% in patients with allergic rhinitis compared with 2.8% in those without allergic rhinitis (aOR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.11-1.25) (Table II and Fig 3 ). Analyses using a stricter definition of current allergic diseases also showed a significantly increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity (see Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Analysis of the effect of atopic status indicated that individuals with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity (aOR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.07-1.71) than those with allergic asthma (aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97-1.17) (Table IV).

Table II.

1:1 propensity-score–matched baseline characteristics, SARS-CoV-2 infection test results, and allergic diseases in all patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing

| Characteristic | Patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 test (total n = 219,959) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma |

Allergic rhinitis |

Atopic dermatitis |

|||||||

| No | Yes | SMD | No | Yes | SMD | No | Yes | SMD | |

| Total, n (%) | 29,570 | 29,570 | 73,527 | 73,527 | 8,436 | 8,436 | |||

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 57.7 ± 20.0 | 57.8 ± 20.0 | 0.005 | 49.7 ± 20.2 | 49.8 ± 20.0 | 0.007 | 52.7 ± 21.0 | 52.7 ± 21.4 | 0.002 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.036 | 0.027 | 0.036 | ||||||

| Male | 12,595 (42.6) | 13,126 (44.4) | 36,797 (50.1) | 37,779 (51.4) | 3,783 (44.8) | 3,936 (46.7) | |||

| Female | 16,975 (57.4) | 16,444 (55.6) | 36,730 (50.0) | 35,748 (48.6) | 4,653 (55.2) | 4,500 (53.3) | |||

| Region of residence, n (%) | 0.011 | 0.164 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Rural | 12,670 (42.9) | 12,830 (43.4) | 32,243 (43.9) | 38,227 (52.0) | 3,353 (39.8) | 3,368 (39.9) | |||

| Urban | 16,900 (57.2) | 16,740 (56.6) | 41,284 (56.2) | 35,300 (48.0) | 5,083 (60.3) | 5,068 (60.1) | |||

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 8,128 (27.5) | 8,175 (27.7) | 0.004 | 11,987 (16.3) | 13,146 (17.9) | 0.042 | 2,225 (26.4) | 2,200 (26.1) | 0.007 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 7,724 (26.1) | 7,928 (26.8) | 0.017 | 10,050 (13.7) | 12,208 (16.6) | 0.083 | 2,006 (23.8) | 2,048 (24.3) | 0.013 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 4,846 (16.4) | 4,922 (16.7) | 0.008 | 7,447 (10.1) | 8,691 (11.8) | 0.056 | 1,271 (15.1) | 1,319 (15.6) | 0.017 |

| History of COPD, n (%) | 6,641 (22.5) | 6,791 (23.0) | 0.014 | 3,203 (4.4) | 4,531 (6.2) | 0.069 | 1,330 (15.8) | 1,342 (15.9) | 0.004 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 13,616 (46.1) | 13,474 (45.6) | 0.010 | 21,987 (29.9) | 22,974 (31.3) | 0.029 | 3,457 (41.0) | 3,404 (40.4) | 0.013 |

| History of chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 2,896 (9.8) | 3,205 (10.8) | 0.037 | 4,723 (6.4) | 5,823 (7.9) | 0.060 | 1,014 (12.0) | 1,095 (13.0) | 0.032 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | 0.010 | 0.078 | 0.012 | ||||||

| 0 | 10,774 (36.4) | 10,523 (35.6) | 42,096 (57.3) | 39,524 (53.8) | 3,419 (40.5) | 3,472 (41.2) | |||

| 1 | 4,056 (13.7) | 4,169 (14.1) | 7,574 (10.3) | 7,570 (10.3) | 1,057 (12.5) | 1,048 (12.4) | |||

| ≥2 | 14,740 (49.8) | 14,878 (50.3) | 23,857 (32.5) | 26,433 (36.0) | 3,960 (46.9) | 3,916 (46.4) | |||

| Previous use of immunosuppressants, n (%) | 686 (2.3) | 740 (2.5) | 0.017 | 1,058 (1.4) | 1,394 (1.9) | 0.035 | 449 (5.3) | 550 (6.5) | 0.057 |

| COVID-19, n (%) | 640 (2.2) | 683 (2.3) | 2,044 (2.8) | 2,415 (3.3) | 209 (2.5) | 189 (2.2) | |||

| Minimally adjusted OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (1.00 - 1.15)∗ | Reference | 1.15 (1.09-1.22)∗ | Reference | 0.90 (0.74-1.10)∗ | |||

| Fully adjusted OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (1.01-1.17)† | Reference | 1.18 (1.11-1.25)‡ | Reference | 0.93 (0.76-1.13)§ | |||

An SMD of <0.1 indicates no major imbalance. All SMD values were <0.1 in each propensity-score–matched cohort.

Numbers in boldface indicate significant differences (P < .05).

Minimally adjusted: adjustment for age and sex.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, asthma, and atopic dermatitis.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

Fig 3.

Association of allergic diseases with the results of SARS-CoV-2 test (primary outcome) among 291,959 patients, and the association of allergic diseases with clinical outcomes of COVID-19 (secondary outcome) among 7,340 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 comprised admission to the ICU, invasive ventilation, or death. NA, Not applicable/available. The x-axis indicates a log-scale.

Table IV.

Propensity-score–matched subgroup analyses for the association of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity with asthma phenotypes among all patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing and clinical outcomes or length of hospital stay with asthma phenotypes among patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Exposure | Event | Event number/total number (%) | Fully adjusted OR∗ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 test | |||

| None | COVID-19 | 640/29,570 (2.2) | Reference |

| Allergic asthma | 603/26,784 (2.3) | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.17) | |

| Nonallergic asthma | 80/2,786 (2.9) | 1.34 (1.07 to 1.71) | |

| Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 | |||

| None | Severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 | 24/537 (4.5) | Reference |

| Allergic asthma | 30/493 (6.1) | 1.40 (0.83 to 2.41) | |

| Nonallergic asthma | 7/44 (15.9) | 4.09 (1.69 to 10.52) | |

| Exposure | Event | Duration (d), crude mean ± SD | Adjusted mean difference∗ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 | |||

| None | Length of stay for patients in hospital | 22.1 ± 14.1 | Reference |

| Allergic asthma | 24.1 ± 16.5 | 0.60 (−1.79 to 0.58) | |

| Nonallergic asthma | 29.3 ± 21.4 | 3.91 (0.40 to 7.42) | |

Numbers in boldface indicate significant differences (P < .05).

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis.

Clinical outcomes in patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2

After propensity score matching among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 7340), there were no major imbalances in the baseline covariates evaluated by SMD between both groups (Table III ; all SMDs < 0.1, except for a history of cerebrovascular disease and hypertension among patients without atopic dermatitis vs those with atopic dermatitis). Table III describes the ORs for the association of severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 with allergic diseases among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2; among these patients, the rates of severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 were 6.9% and 4.5% in patients with and without asthma, respectively (aOR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.01-2.67) and 4.7% and 3.7% in patients with and without allergic rhinitis, respectively (aOR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.00-1.64, P < .05) (Table III and Fig 3). Furthermore, analyses using a stricter definition of current allergic diseases showed a significantly increased risk of severe outcomes of COVID-19 (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The analysis of the effect of atopic status indicated that individuals with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk for severe outcomes of COVID-19 (aOR, 4.09; 95% CI, 1.69-10.52) than those with allergic asthma (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.83-2.41) (Table IV ).

Table III.

1:1 propensity-score–matched baseline characteristics, severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19, and length of stay for patients and allergic diseases among patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Characteristic | Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (total n = 7340) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma |

Allergic rhinitis |

Atopic dermatitis |

|||||||

| No | Yes | SMD | No | Yes | SMD | No | Yes | SMD | |

| Total, n (%) | 537 | 537 | 2176 | 2176 | 154 | 154 | |||

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 50.6 ± 18.35 | 51.1 ± 18.0 | 0.029 | 44.1 ± 18.6 | 45.0 ± 18.2 | 0.046 | 43.5 ± 18.8 | 44.7 ± 19.7 | 0.063 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.062 | 0.012 | 0.040 | ||||||

| Male | 168 (31.3) | 184 (34.3) | 849 (39.0) | 862 (39.6) | 67 (43.5) | 64 (41.6) | |||

| Female | 369 (68.7) | 353 (65.7) | 1327 (61.0) | 1314 (60.4) | 87 (56.5) | 90 (58.4) | |||

| Region of residence, n (%) | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.065 | ||||||

| Rural | 238 (44.3) | 239 (44.5) | 1081 (49.7) | 1050 (48.3) | 79 (51.3) | 84 (54.6) | |||

| Urban | 299 (55.7) | 298 (55.5) | 1095 (50.3) | 1126 (51.8) | 75 (48.7) | 70 (45.5) | |||

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 92 (17.1) | 98 (18.3) | 0.030 | 178 (8.2) | 180 (8.3) | 0.003 | 15 (9.7) | 17 (11.0) | 0.038 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 47 (8.8) | 48 (8.9) | 0.006 | 80 (3.7) | 69 (3.2) | 0.020 | 7 (4.6) | 10 (6.5) | 0.072 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 34 (6.3) | 47 (8.8) | 0.086 | 102 (4.7) | 105 (4.8) | 0.006 | 2 (1.3) | 8 (5.2) | 0.167 |

| History of COPD, n (%) | 19 (3.5) | 24 (4.5) | 0.029 | 25 (1.2) | 24 (1.1) | 0.002 | 5 (3.3) | 7 (4.6) | 0.048 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 133 (24.8) | 149 (27.8) | 0.067 | 367 (16.9) | 364 (16.7) | 0.003 | 27 (17.5) | 34 (22.1) | 0.106 |

| History of chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 18 (3.4) | 26 (4.8) | 0.067 | 38 (1.8) | 46 (2.1) | 0.020 | 6 (3.9) | 4 (2.6) | 0.064 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | 0.093 | 0.052 | 0.019 | ||||||

| 0 | 321 (59.8) | 290 (54.0) | 1681 (77.3) | 1536 (70.6) | 113 (73.4) | 107 (69.5) | |||

| 1 | 69 (12.9) | 78 (14.5) | 182 (8.4) | 295 (13.6) | 17 (11.0) | 20 (13.0) | |||

| ≥2 | 147 (27.4) | 169 (31.5) | 313 (14.4) | 345 (15.9) | 24 (15.6) | 27 (17.5) | |||

| Previous use of immunosuppressants, n (%) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 0.048 | 9 (0.4) | 10 (0.5) | 0.006 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.062 |

| Severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19, n (%) | 24 (4.5) | 37 (6.9) | 81(3.7) | 103 (4.7) | 5(3.3) | 7(4.6) | |||

| Minimally adjusted OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.56 (0.95 to 2.62)∗ | Reference | 1.29 (1.02 to 1.66)∗ | Reference | 1.16 (0.34 to 4.15)∗ | |||

| Fully adjusted OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.62 (1.01 to 2.67)† | Reference | 1.27 (1.00 to 1.64)‡ | Reference | 0.72 (0.18 to 2.90)§ | |||

| Length of stay for patients in hospital (d), mean ± SD | 22.1 ± 14.1 | 24.6 ± 17.0 | 21.8 ± 14.3 | 22.8 ± 14.5 | 22.4 ± 14.4 | 22.3 ± 14.6 | |||

| Fully adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | Reference | 0.89 (−0.25 to 2.03)† | Reference | 0.71 (0.02 to 1.40)‡ | Reference | −0.01 (−2.07 to 2.04)§ | |||

An SMD of <0.1 indicates no major imbalance. All SMD values were <0.1 in each propensity-score–matched cohort, except history of cerebrovascular disease and hypertension among patients without atopic dermatitis vs those with atopic dermatitis.

Numbers in boldface indicate significant differences (P < .05).

Minimally adjusted: adjustment for age and sex.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, asthma, and atopic dermatitis.

Fully adjusted: adjustment for age, sex, region of residence, history of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, Charlson comorbidity index, use of immunosuppressants, use of systemic glucocorticoids, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

To gain additional insights into the association between allergic diseases and the clinical outcomes of COVID-19, we conducted an analysis of the length of hospital stay (Table III). Patients with allergic rhinitis were hospitalized for an average of 22.8 days, as compared with an average hospital stay of 21.8 days in patients without allergic rhinitis (adjusted mean difference, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.02-1.40). The mean length of hospital stay was 24.6 days and 22.1 days in patients with and without asthma (adjusted mean difference, 0.89; 95% CI, −0.25 to 2.3) and 22.3 days and 22.4 days in patients with and without atopic dermatitis (adjusted mean difference, −0.01; 95% CI, −2.07 to 2.04), respectively.

Discussion

In a Korean nationwide cohort, we investigated the association between SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and allergic diseases among 219,959 patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing. Moreover, we studied the association between the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 and allergic diseases among 7340 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with an increased likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and worse clinical outcomes (ie, death, ICU admission, and invasive ventilation). Allergic rhinitis was associated with longer hospital stay. Interestingly, patients with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 than those with allergic asthma.

COVID-19 was associated with several comorbidities, such as old age1 , 4 and preexisting pulmonary disease5 , 6; however, studies of the association of COVID-19 and asthma are controversial, because previous studies have described either no association15 or a positive association.33 , 34 Moreover, previous studies on this topic were limited by their small sample of COVID-19–confirmed patients (n = 140,15 n = 179,33 or n = 2334 vs n = 7340 in the present study), making it difficult to reach a consistent conclusion regarding association (no association15 or positive association33 , 34). For example, a previous study in Wuhan that was conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic showed no COVID-19 risk association with an allergic history15; however, more recent epidemiological data indicate that asthma is a significant comorbidity related to COVID-19.33 In addition, a cellular receptor of COVID-19, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, is decreased,34 whereas the expression of another entry molecule, TMPRSS2, is increased in the nasal and airway epithelial cells of children and adults with asthma and allergic rhinitis.22 We hypothesized that the increased number of cases with adequate clinical information in combination with the precise study design of this research could clarify this inconsistency. No study has yet demonstrated a direct relationship between infectivity or clinical outcomes of COVID-19 and with a comprehensive set of allergic disorders (including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis) by using propensity score matching at a national level together with a subgroup analysis of asthma. This study highlights 2 important findings: (1) current or underlying asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with a higher likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and severe COVID-19 outcomes; and (2) individuals with nonallergic asthma were more likely to test positive and experience severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Several possible pathophysiological mechanisms in the underlying allergic history could enhance the susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection.21 These respiratory viruses enter the bronchial epithelium of the upper and lower airway and provoke local inflammatory cascades that are characterized by neutrophil recruitment, T-lymphocyte trafficking, and activation of resident monocytes to induce a disruption of the bronchial defense system.21 By inducing cytokines such as IL-25 and IL-33 in epithelial cells, the virus activates TH2 pathways to cause eosinophilia, increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (ie, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13), and enhanced mucin production, all of which eventually worsen the symptoms of asthma.35 Moreover, patients with allergies have impaired secretion of innate IFNs, such as IFN-I and IFN-III, in mononuclear cells as well as in the epithelial cells of the airway, which increases their susceptibility to respiratory viral infection.21 These IFNs are crucial for stimulating the expression of antiviral activity-related genes through a well-known Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway in the bronchial epithelial cells and alveolar cells.36 On the basis of these preliminary studies, we theorized that SARS-CoV-2 itself could potentially exacerbate allergy, which could, in turn, facilitate viral infection and lead to a devastating outcome of COVID-19. Although in the same category of allergic diseases, it is remarkable that atopic dermatitis does not show a potential association with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19, implying that changes in the local immunologic environment in the respiratory system, including the upper and lower respiratory tract, appear to be more important in the progression of infection than the systemic immunologic effects. The results of our nationwide cohort analysis clearly show that patients with respiratory allergic diseases are at a higher risk for worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Interestingly, our data showed that patients with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 than those with allergic asthma. These results are in line with those from a previous study.17 Compared with allergic asthma, nonallergic asthma involves the activation of neutrophils and mast cells, which drives the immune response toward a TH1 response.37 Because the immunologic profile of patients with COVID-19 is polarized toward a classic TH1 response, patients with nonallergic asthma might manifest an aggravated TH1 immune response. Thus, they are predisposed to severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19.38 Given these potential associations, patients with nonallergic asthma should be aware of the severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19, and careful monitoring of inflammatory status in this population should be emphasized.

This study has several limitations. First, the most important limitation is that the diagnosis of asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis was defined by ICD codes, which may be inaccurate when compared with the diagnosis obtained from a review of a questionnaire. However, many previous studies have used claims-based definitions of allergic diseases similarly as in our study,25 , 30 and have demonstrated good reliability. Because we have not interpreted the allergic status of the patients on the basis of their medical records, comprising laboratory data (eg, IgE levels), our results should be interpreted with caution and should be validated in studies that involve the analysis of laboratory data. To overcome this limitation, we have adopted a novel “allergic asthma” concept, which could represent partially the severity of an allergic reaction.17 , 28 Second, despite the sufficient amount of pediatric data (number of COVID-19–confirmed patients = 611), the association between pediatric allergic diseases and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 could not be analyzed because none of the children had any of the 3 specified composite end points (admission to ICU, administration of invasive ventilation, or death). Although we investigated the relationship between allergic status and length of hospital stay, the association was inconclusive (data not shown). Further large-scale international cohort studies in pediatric patients with COVID-19 with diverse medical outcomes are needed to clarify this issue. Third, because our data were claims-based, information on smoking was unavailable. The Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea exclude information on smoking because of the governmental policy for protecting the personal information of patients. To compensate for this issue, we adjusted the patient’s history of COPD, a well-known smoking-related disease.26 , 39 Fourth, because of the urgent global situation, the COVID-19–related data provided by the Korean government involve short-term data (<3.5 years) of the patient’s history for quick claim processing. More clinical studies involving longer follow-up data are required to provide more information and to validate the association between allergic diseases and COVID-19. Finally, because our database involves patients who underwent the SARS-CoV-2 test, systemic factors might differ in comparison to those of the general population. Despite this potential prevalence-induced bias, our study involved a large population-based cohort with propensity score matching to ensure that our results were highly credible.

In spite of these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to investigate the association of the risk of COVID-19 with allergic diseases in all Korean patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by using data from a Korean nationwide cohort. The strength of our cohort study was the large sample size (219,959 patients). Thus, our study provides strong evidence that the development of respiratory allergic diseases is associated with an increased risk of subsequent COVID-19 and/or worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Conclusions

Asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with an increased likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in a Korean nationwide cohort. Especially, patients with nonallergic asthma had a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 than those with allergic asthma. Thus, our findings provide an improved understanding of the relationship between the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and respiratory allergic diseases and suggest that clinicians should be aware of the greater risk of susceptibility to, and severity of, COVID-19 that is conferred by respiratory allergic diseases, especially nonallergic asthma, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clinical implications.

Our findings suggest that clinicians should be aware of the greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 among patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma, especially nonallergic asthma.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate health care professionals dedicated to treating patients with COVID-19 in Korea, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea for sharing invaluable national health insurance claims data in a prompt manner.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (grant no. NRF2019R1G1A109977912). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Fig E1.

Fig E2.

Fig E3.

Fig E4.

Fig E5.

Fig E6.

Fig E7.

Fig E8.

Fig E9.

Fig E10.

Fig E11.

Fig E12.

References

- 1.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S.E. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; coronavirus disease-19) Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:119–124. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 72. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331685/nCoVsitrep01Apr2020-eng.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Liu H., Wu Y., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W.-J., Liang W.-H., Zhao Y., Liang H.-R., Chen Z.-S., Li Y.-M., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehra M.R., Desai S.S., Kuy S., Henry T.D., Patel A.N. Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Lighter J., Phillips M., Hochman S., Sterling S., Johnson D., Francois F., et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:896–897. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai M., Liu D., Liu M., Zhou F., Li G., Chen Z., et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-COV-2: a multi-center study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:783–791. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vardavas C.I., Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:20. doi: 10.18332/tid/119324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akalin E., Azzi Y., Bartash R., Seethamraju H., Parides M., Hemmige V., et al. Covid-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2475–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco J.L., Ambrosioni J., Garcia F., Martínez E., Soriano A., Mallolas J., et al. COVID-19 in HIV Investigators. COVID-19 in patients with HIV: clinical case series. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e314–e316. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galli S.J., Tsai M., Piliponsky A.M. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:445–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J.-J., Dong X., Cao Y.-Y., Yuan Y.-D., Yang Y.-B., Yan Y.-Q., et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75:1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X., Xu S., Yu M., Wang K., Tao Y., Zhou Y., et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Z., Hasegawa K., Ma B., Fujiogi M., Camargo C.A., Jr., Liang L. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:327–329.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K., et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juhn Y.J. Risks for infection in patients with asthma (or other atopic conditions): is asthma more than a chronic airway disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:247–257.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung D.Y., Boguniewicz M., Howell M.D., Nomura I., Hamid Q.A. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Investig. 2004;113:651–657. doi: 10.1172/JCI21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards M.R., Strong K., Cameron A., Walton R.P., Jackson D.J., Johnston S.L. Viral infections in allergy and immunology: how allergic inflammation influences viral infections and illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:909–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura H., Francisco D., Conway M., Martinez F.D., Vercelli D., Polverino F., et al. Type 2 inflammation modulates ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:80–88.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SW, Ha EK, Yeniova A, Moon SY, Kim SY, Koh HY, et al. Severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 associated with proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study with propensity score matching [published online ahead of print July 30, 2020]. Gut. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lee S.W., Yon D.K., James C.C., Lee S., Koh H.Y., Sheen Y.H., et al. Short-term effects of multiple outdoor environmental factors on risk of asthma exacerbations: age-stratified time-series analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1542–1550.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung C.R., Chen W.T., Tang Y.H., Hwang B.F. Fine particulate matter exposure during pregnancy and infancy and incident asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:2254–2262.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo A, Lee SW, Koh HY, Kim MA, Han MY, Yon DK. Incidence of cancer after asthma development: 2 independent population-based cohort studies [published online ahead of print May 15, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Roumie C.L., Chipman J., Min J.Y., Hackstadt A.J., Hung A.M., Greevy R.A., et al. Association of treatment with metformin vs sulfonylurea with major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes and reduced kidney function. JAMA. 2019;322:1167–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh H.Y., Kim T.H., Sheen Y.H., Lee S.W., An J., Kim M.A., et al. Serum heavy metal levels are associated with asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, allergic multimorbidity, and airflow obstruction. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2912–2915.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha J., Lee S.W., Yon D.K. Ten-year trends and prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis among the Korean population, 2008-2017. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:278–283. doi: 10.3345/cep.2019.01291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H.J., Ahn H.S., Kang T., Bachert C., Song W.-J. Nasal polyps and future risk of head and neck cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1004–1010.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds H.R., Adhikari S., Pulgarin C., Troxel A.B., Iturrate E., Johnson S.B., et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2441–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almeida A.N., Bravo-Ureta B.E. Assessing the sensitivity of matching algorithms: the case of a natural resource management programme in Honduras. Stud Agr Econ. 2017;119:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garg S., Kim L., Whitaker M., O’Halloran A., Cummings C., Holstein R., et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson D.J., Busse W.W., Bacharier L.B., Kattan M., O’Connor G.T., Wood R.A., et al. Association of respiratory allergy, asthma and expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:203–206.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson D.J., Makrinioti H., Rana B.M., Shamji B.W., Trujillo-Torralbo M.-B., Footitt J., et al. IL-33–dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1373–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Contoli M., Message S.D., Laza-Stanca V., Edwards M.R., Wark P.A., Bartlett N.W., et al. Role of deficient type III interferon-λ production in asthma exacerbations. Nat Med. 2006;12:1023–1026. doi: 10.1038/nm1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amin K., Lúdvíksdóttir D., Janson C., Nettelbladt O., Björnsson E., Roomans G.M., et al. Inflammation and structural changes in the airways of patients with atopic and nonatopic asthma. BHR Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2295–2301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9912001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., Mateus J., Dan J.M., Moderbacher C.R., et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181:1489–1501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calverley P.M.A. AJRCCM: 100-year anniversary. Physiology and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the blue journals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1088–1090. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0114ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.