Abstract

The indolocarbazole family of bisindole alkaloids is best known for the natural product staurosporine, a protein kinase C inhibitor that belongs to the indolo[2,3-a]carbazole structural class. A large number of other indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles have subsequently been isolated and identified, but other isomeric forms of indolocarbazole natural products have rarely been reported. An extract of the marine sponge Damiria sp., which represents an understudied genus, provided two novel alkaloids named damirines A (1) and B (2). Their structures were assigned by comprehensive NMR spectroscopic analyses, and for compound 2 this included application of the LR-HSQMBC pulse sequence, a long-range heteronuclear correlation experiment that has particular utility for defining proton-deficient scaffolds. The damirines represent a new hexacyclic carbon-nitrogen framework comprised of an indolo[3,2-a]carbazole fused with either an aminoimidazole or a imidazolone ring. Compound 1 showed selective cytotoxic properties toward six different cell lines in the NCI-60 cancer screen.

Keywords: Indolocarbazole, LR-HSQMBC, Damiria, damirine

1. INTRODUCTION

The indolocarbazole family of alkaloids has been the focus of numerous drug discovery and development studies since staurosporine (3), an indolo[2,3-a]carbazole compound joined with an amino sugar residue, was isolated in 1977[1] and subsequently found to exhibit a wide range of biological activities including inhibition of protein kinase C, along with cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and anti-parasitic activities.[2] Structurally, the indolocarbazoles are carbon-nitrogen heterocycles characterized by an indole unit fused to one of the benzenoid rings of a carbazole moiety.[3] Five indolocarbazole isomers are defined based on the position and orientation of the indole and carbazole ring fusion, including indolo[2,3-a]carbazole, indolo[3,2-a]carbazole, indolo[3,2-b]carbazole, indolo[2,3-b]carbazole and indolo[2,3-c]carbazole.[3–4] Over the last 40 years, almost all of the indolocarbazoles isolated from nature are indolo[2,3-a]carbazoles, therefore interest in the chemistry and pharmacology of these alkaloids has been primarily focused on this structural class. The other indolocarbazole isomers have received only limited attention.[4]

The marine sponge genus Damiria has rarely been investigated chemically, and the only compounds previously reported from a Damiria sponge are the pyrroloquinoline alkaloids damirones A and B.[5] Fractionation of the organic solvent extract of a collection of Damiria sp. made in Thailand provided two novel compounds, damirines A (1) and B (2), which belong to the indolo[3,2-a]carbazole class. Although the indolocarbazole scaffolds have been synthesized since the 1950s,[6] the first natural indolo[3,2-a]carbazole, ancorinazole, was reported from the New Zealand sponge Ancoina sp. in 2002.[7] Three additional members of this class were described in 2013, including asteropusazoles A and B from the Bahamas sponge Asteropus sp.,[8] and racemosin B from the Chinese green alga Caulerpa racemosa.[9] This paper describes the structure elucidation and comprehensive NMR characterization of the sponge metabolites damirines A (1) and B (2), including utilization of long-range heteronuclear correlation data from HMBC and LR-HSQMBC experiments optimized for small 1H-13C couplings.[10]

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Damiria sp. extract was active in an assay for growth inhibition against EpCAM(+) hepatocellular carcinoma cells so it was selected for further chemical study.[11] Sequential chromatography of the extract on a diol solid phase extraction (SPE) support, followed by C18 reversed-phase HPLC provided damirines A (1) and B (2).

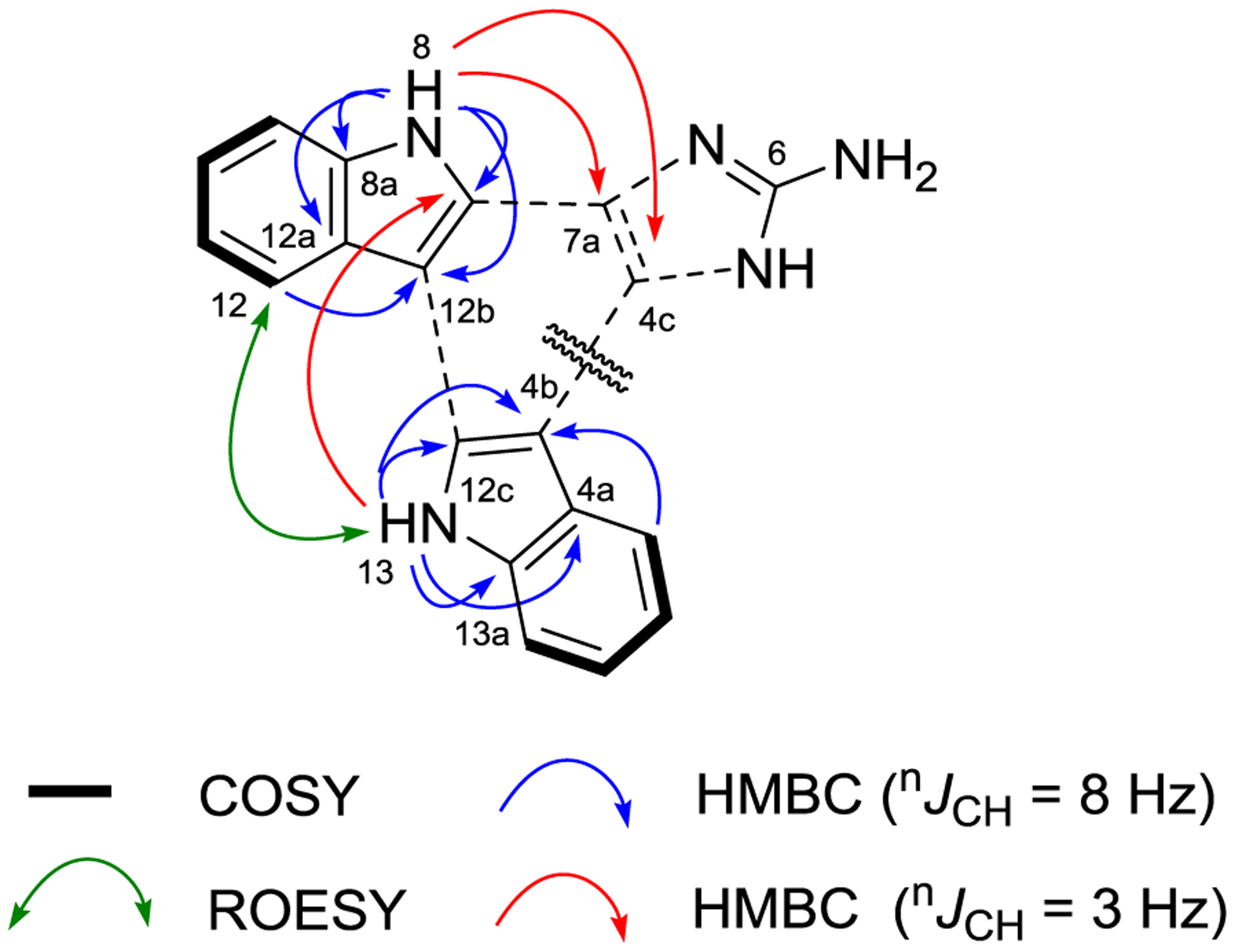

Damirine A (1) was purified as an optically inactive brown amorphous powder. Its molecular formula was established as C19H13N5 based on (+)-HRESIMS data, which required 16 degrees of unsaturation. The UV spectrum of 1 revealed absorption maxima at λ = 213, 243, 271, 293, 307 and 340 nm, consistent with extended conjugation of a polycyclic aromatic molecule. The highly aromatic character of 1 was further confirmed by the presence of only sp2 carbons in the 13C NMR spectrum, with chemical shifts between 101.4 and 153.0 ppm (Table 1). The gCOSY spectrum revealed two sets of ABCD proton-proton spin systems [δH 7.55 (d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.30 (dd, J = 7.2, 7.8 Hz), 7.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz) and 8.57 (d, J = 7.2 Hz)] and [δH 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.29 (dd, J = 7.2, 7.8 Hz), 7.19 (dd, J = 7.2, 7.8 Hz) and 8.44 (d, J = 7.8 Hz)]. HMBC correlations for these aromatic protons and for two exchangeable protons NH-8 (δH 11.86) and NH-13 (δH 11.51) were consistent with the presence of two 2,3-disubstituted-indole moieties (Table 1). A key ROESY correlation between H-12/NH-13 and a four-bond HMBC correlation for NH-13/C-7b that was observed when the pulse sequence was optimized for long-range correlations (nJCH = 3 Hz), established a linkage between C-12b and C-12c (Figure 2). The long-range optimized HMBC experiment also showed correlations from NH-8/C-4c and NH-8/C-7a, which helped define the fully substituted C ring in 1. However, no other protons correlated with these two carbons and no correlations were observed with the remaining C-6 quaternary carbon. Consideration of the characteristic downfield 13C chemical shift (δC 153.0) in the remaining CH3N3 moiety, and the requirement for two more unsaturation equivalents in 1, suggested that the last structural component was an amino-substituted imidazole ring. Thus, the hexacyclic structure of 1 was assigned as an indolo[3,2-a]carbazole with an imidazole (ring F) fused on ring C. Comparison of experimentally measured δC values with carbon chemical shifts calculated by density functional theory (DFT) methods (Table 2) provided additional support for the assigned structure of damirine A (1).

TABLE 1.

NMR spectroscopic data (600 MHz 1H, 150 MHz 13C, DMSO-d6) for damirine A (1)

| Position | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | ROESY | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110.6, CH | 7.62, d (7.8) | 13 | 3, 4a, 4ba, 13aa |

| 2 | 122.2, CH | 7.29, dd (7.2, 7.8) | 1, 4, 13a, 4aa | |

| 3 | 118.4, CH | 7.19, dd (7.2, 7.8) | 1, 4, 4a, 4ba, 13aa | |

| 4 | 120.0, CH | 8.44, d (7.8) | 2, 4b, 13a, 1a | |

| 4a | 121.9, C | |||

| 4b | 101.7, C | |||

| 4c | 123.2, C | |||

| 5 | b | |||

| 6 | 153.0, C | |||

| 7 | b | |||

| 7a | 116.7, C | |||

| 7b | 127.8, C | |||

| 8 | 11.86, s | 9 | 7b, 8a, 12a, 12b, 7aa, 4ca | |

| 8a | 138.3, C | |||

| 9 | 110.7, CH | 7.55, d (7.8) | 8 | 11, 12a, 8aa, 12ba |

| 10 | 122.4, CH | 7.30, dd (7.2, 7.8) | 8a, 9, 12, 12aa | |

| 11 | 118.5, CH | 7.24, t (7.2) | 9, 12, 12a, 8aa, 12ba | |

| 12 | 120.0, CH | 8.57, d (7.2) | 13 | 8a, 10, 12b, 9a |

| 12a | 122.7, C | |||

| 12b | 101.4, C | |||

| 12c | 129.8, C | |||

| 13 | 11.51, s | 1, 12 | 4a, 4b, 12c, 13a, 1a, 7ba | |

| 13a | 138.6, C |

Observed with nJCH = 3 Hz.

Not observed.

FIGURE 2.

Key COSY, HMBC, and ROESY correlations for damirine A (1)

TABLE 2.

Comparison of experimental and DFT calculated 13C and 1H chemical shifts in DMSO-d6 for damirine A (1)

| Position | δC (exp.) | δC (calc.) | δH (exp.) | δH (calc.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110.6 | 108.9 | 7.62 | 7.63 | |

| 2 | 122.2 | 122.5 | 7.29 | 7.31 | |

| 3 | 118.4 | 118.6 | 7.19 | 7.19 | |

| 4 | 120.0 | 119.1 | 8.44 | 8.41 | |

| 4a | 121.9 | 121.3 | |||

| 4b | 101.7 | 99.5 | |||

| 4c | 123.2 | 125.9 | |||

| 6 | 153.0 | 150.2 | |||

| 7a | 116.7 | 122.7 | |||

| 7b | 127.8 | 129.1 | |||

| 8a | 138.3 | 138.5 | |||

| 9 | 110.7 | 109.0 | 7.55 | 7.55 | |

| 10 | 122.4 | 122.8 | 7.30 | 7.32 | |

| 11 | 118.5 | 118.9 | 7.24 | 7.21 | |

| 12 | 120.0 | 119.2 | 8.57 | 8.59 | |

| 12a | 122.7 | 123.1 | |||

| 12b | 101.4 | 100.2 | |||

| 12c | 129.8 | 130.1 | |||

| 13a | 138.6 | 138.2 | |||

| R2 | 0.9759 | 0.9983 |

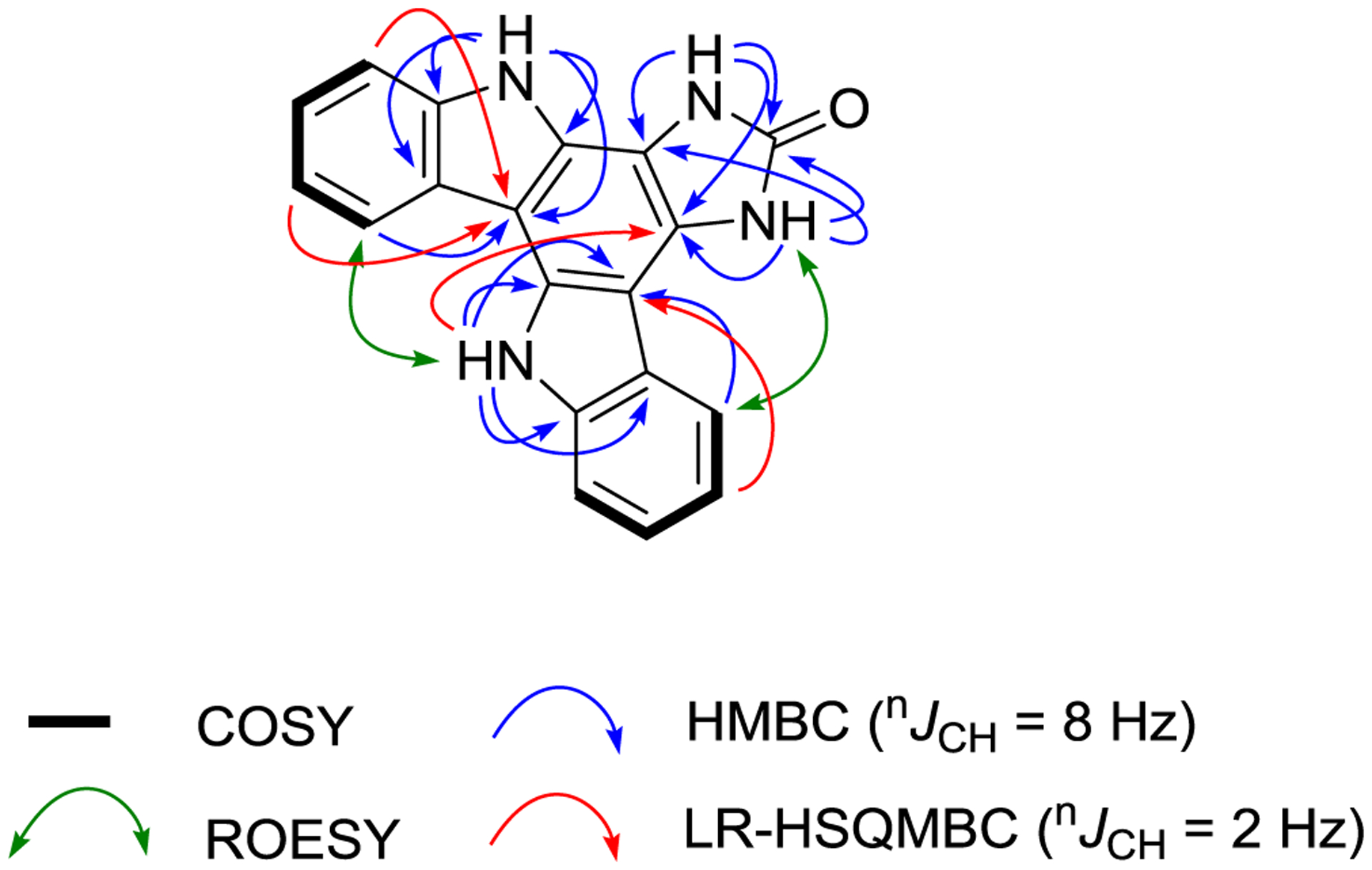

Damirine B (2) was isolated as a brown powder with a molecular formula established by (+)-HRESIMS measurements of C19H12N4O. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 (Table 3) were very similar to those recorded for 1, except for the presence of two additional exchangeable protons at δH 11.32 and 11.82, corresponding to NH-5 and NH-7, respectively. The 1H–15N HSQC spectrum confirmed the presence of four readily observable NH protons in 2. Following extensive 1D and 2D NMR analyses, the same indolo[3,2-a]carbazole scaffold found in 1 was confirmed in damirine B (2). Key HMBC correlations including those from NH-8 and NH-13 helped define the fused B, C, and D rings of the indolocarbazole system, while a ROESY between H-12 and NH-13 revealed the relative orientation of the two indoles. The molecular formula of 2 required the addition of oxygen and the loss of NH relative to the molecular formula of 1. This was consistent with replacement of the ring F amine substituent in 1, whose NH protons were never observable, with a carbonyl group to give an imidazolone moiety in 2, with NH protons that were facile to observe in DMSO-d6. HMBC correlations from NH-5 and NH-7 in ring F to C-4c, C-7a and the C-6 carbonyl (δC 155.8), along with a ROESY correlation between H-4 and NH-5 supported this assignment. Application of the recently described LR-HSQMBC NMR pulse sequence provided further evidence for the structure of damirine B (2).[10] The LR-HSQMBC experiment facilitates detection of long-range (4-bond and 5-bond) heteronuclear couplings that generally are not observed in HMBC spectra, so it has particular utility in structural studies of proton-deficient scaffolds. It has been successfully employed in several structural studies of novel natural products, which illustrated the importance of the additional heteronuclear correlations this technique can provide.[12] A 1H-13C LR-HSQMBC experiment with 2 (optimized for nJC,H = 2 Hz) provided a number of additional 4-bond correlations, including a key one from NH-13 to C-4c, that reinforced the structure assigned to damirine B (2).

TABLE 3.

NMR spectroscopic data (600 MHz 1H, 150 MHz 13C, DMSO-d6) for damirine B (2)

| Position | δC, type | δNa | δH (J in Hz) | ROESY | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110.4, CH | 7.61, d (7.8) | 13 | 3, 4a | |

| 2 | 122.5, CH | 7.30, t (7.8) | 1, 4, 13a | ||

| 3 | 118.3, CH | 7.16, t (7.8) | 1, 4a, 4b, 4bb, 13ab | ||

| 4 | 120.1, CH | 8.48, d (7.8) | 5 | 2, 4b, 13a | |

| 4a | 121.5, C | ||||

| 4b | 100.0, C | ||||

| 4c | 120.7, C | ||||

| 5 | 123.0 | 11.32, s | 4 | 4c, 6, 7a | |

| 6 | 155.8, C | ||||

| 7 | 117.3 | 11.82, s | 4c, 6, 7a | ||

| 7a | 107.5, C | ||||

| 7b | 125.3, C | ||||

| 8 | 118.2 | 12.73, s | 9 | 7b, 8a, 12a, 12b | |

| 8a | 138.8, C | ||||

| 9 | 110.6, CH | 7.55, d (7.8) | 8 | 11, 12a, 12bb | |

| 10 | 122.5, CH | 7.32, dd (7.2, 7.8) | 8a, 9, 12, 12ab | ||

| 11 | 118.3, CH | 7.23, dd (7.2, 7.8) | 9, 12a, 8ab, 12bb | ||

| 12 | 120.0, CH | 8.56, d (7.8) | 13 | 8a, 10, 12b | |

| 12a | 122.4, C | ||||

| 12b | 101.4, C | ||||

| 12c | 129.9, C | ||||

| 13 | 116.6 | 11.56, s | 1, 12 | 4a, 4b, 12c, 13a, 4cb | |

| 13a | 138.7, C |

Determined with 1H–15N HSQC.

Observed by LR-HSQMBC optimized for 2 Hz.

Damirine A (1) showed modest growth inhibitory activity against Hep3B (EpCAM-positive) hepatocellular carcinoma cells, thus compounds 1 and 2 were subsequently screened for growth inhibitory activity in the NCI-60 cell line anticancer screen.[13] Damirine A (1) was sufficiently active to be selected for full 5-dose testing against all 60 cancer cell lines, where it exhibited selective cytotoxic activity and was most effective at inhibiting the growth of one melanoma (MALME-3M, 50% growth inhibition, GI50 = 1.9 μM), one breast (MDA-MB-468, GI50 = 2.0 μM), two colon (SW-620, GI50 = 3.3 μM; HCC-2998, GI50 = 2.3 μM), and two leukemia (MOLT-4, GI50 = 1.9 μM; K-562, GI50 = 2.2 μM) cell lines (see Supporting Information).

3. CONCLUSIONS

Damirines A (1) and B (2) were isolated from the sponge Damiria sp. and their structures were unambiguously solved using a combination of NMR methodologies. The sparse distribution of observable protons in the core of these novel hexacyclic bisindole alkaloids necessitated the acquisition of long-range (> three bonds) 1H-13C heteronuclear correlation data. Two different experimental approaches were employed, one using HMBC optimized for 3 Hz couplings, and the other using the LR-HSQMBC pulse sequence optimized for 2 Hz couplings, to obtain the desired spectroscopic data. These long-range correlations allowed assignment of damirine A (1) as an indolo[3,2-a]carbazole fused to an aminoimidazole ring, while damirine B (2) had the same indolocarbazole core fused to an imidazolone moiety. While the indolo[3,2-a]carbazole scaffold has been generated in prior synthetic studies,[6, 14] it has only rarely been found in a natural product. Damirines A (1) and B (2) provide new carbon-nitrogen skeletons not seen in any other reported secondary metabolites, and damirine A (1) exhibited selective growth inhibitory effects against six different cancer cell lines.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PART

NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometer equipped with a 3 mm TCI 1H/13C/15N cryogenic probe and operating at 600 MHz for 1H and 150 MHz for 13C. Spectra were calibrated to residual solvent signals at δH 2.50 and δC 39.5 (DMSO-d6). HMBC experiments were optimized for nJCH = 8.3 Hz, unless otherwise indicated. 15N assignments were based on 1H−15N HSQC correlations with 1JNH = 90 Hz. The δN values were not calibrated to an external standard but were referenced to neat NH3 (δ 0.00) using the standard Bruker parameters. The 1H-13C LR-HSQMBC experiment was optimized for nJC,H = 2.0 Hz, with 768 increments in the f1 dimension. Preparative reversed-phase HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC or a Gilson PLC system using a Phenomenex Luna-C18 (5μ, 100Å, 250 × 10 mm) column with the indicated gradient. UV and IR spectra were measured with a Thermo Scientific Nanodrop 2000C spectrophotometer and a Bruker ALPHA II FT-IR spectrometer, respectively. (+)-HRESIMS data were acquired on an Agilent Technology 6530 Accurate-mass Q-TOF LC/MS.

Specimens of the sponge Damiria sp. were collected around Phuket Island, Thailand in April 2014, under contract through the Coral Reef Research Foundation for the Natural Products Branch, National Center Institute. A voucher specimen (voucher ID # 0YYA1139; NSC # C034303) was deposited at the Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C. The sponge sample (683 g, wet weight) was extracted according to the procedures detailed by McCloud to give 2.62 g of organic solvent (CH2Cl2-MeOH, 1:1 and 100% MeOH) extract.[15] A portion of the organic extract (900 mg) was fractionated on diol SPE cartridges (2 g) eluting with 9:1 hexane-CH2Cl2, 20:1 CH2Cl2-EtOAc, 100% EtOAc, 5:1 EtOAc-MeOH, and 100% MeOH in a stepwise manner. Final purification was achieved by C18 HPLC of the MeOH fraction (347.2 mg) with a linear H2O/CH3CN gradient (0.1% formic acid) from 10 to 50% CH3CN over 22 minutes to give a total of 9.2 mg of damirine A (1) and 2.4 mg of damirine B (2). An additional 1.2 mg of 1 (TFA salt) was obtained by C18 HPLC eluted with a linear H2O/CH3CN gradient (0.5% TFA) from 40 to 50% CH3CN over 20 minutes.

Damirine A (1): brown solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 213 (5.27), 243 (5.36), 271 (5.40), 293 (5.26), 307 (5.23), 340 (4.72); IR (neat) νmax 3305 (br), 1681, 1581, 1380, 1349, 1264 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 312.1249 [M + H]+ (calcd for C19H14N5, 312.1244).

Damirine B (2): brown solid; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 215 (4.88), 244 (4.88), 269 (4.91), 288 (4.78), 340 (4.22), 355 (4.32); IR (neat) νmax 3340 (br), 1643, 1370, 1281 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, Table 3; HRESIMS m/z 313.1081 [M + H]+ (calcd for C19H13N4O, 313.1084).

Computational Details.

Molecular mechanics were performed using Macromodel interfaced to the Maestro program (Version 2015.3, Schrödinger). Conformational searches used the OPLS_2005 force field. Only one conformer was found within 3 kcal/mol of internal relative energies. The conformer was then subjected to geometry optimization in DMSO solution on Gaussian 09 at the DFT level with the B3LYP functional and the 6–31G(d) basis set. Single point calculations in DMSO with the B3LYP functional and the 6–311G(d,p) basis set were then employed to provide the shielding constants of carbon and proton nuclei. Meanwhile, the same procedure was applied on tetramethylsilane (TMS) and benzene. The theoretical chemical shifts were calculated using the equation δxcalc = σref − σx + δref; where δxcalc is the calculated chemical shift for nucleus x; σx is the shielding constant for nucleus x; σref and δref are the shielding constant and chemical shift of the reference compound (TMS or benzene) computed at the same level of theory.[16] Calculated shielding constants of references in DMSO are σCTMS = 184.70015, σCbenzene = 49.37645, σHTMS = 31.94609 and σHbenzene = 24.26277 ppm; Chemical shifts of references in DMSO are δCTMS = 0, δCbenzene = 128.3, δHTMS = 0 and δHbenzene = 7.37 ppm.[17] Systematic errors during the chemical shift calculation were removed by empirical scaling according to δcalc* = (δcalc – b)/a; where the slope (a), the intercept (b) and the correlation coefficient (R2) were determined from a plot of δcalc against δexp. The mean absolute error (MAE) was defined as . The corrected mean absolute error (CMAE) was defined as .[18]

Supplementary Material

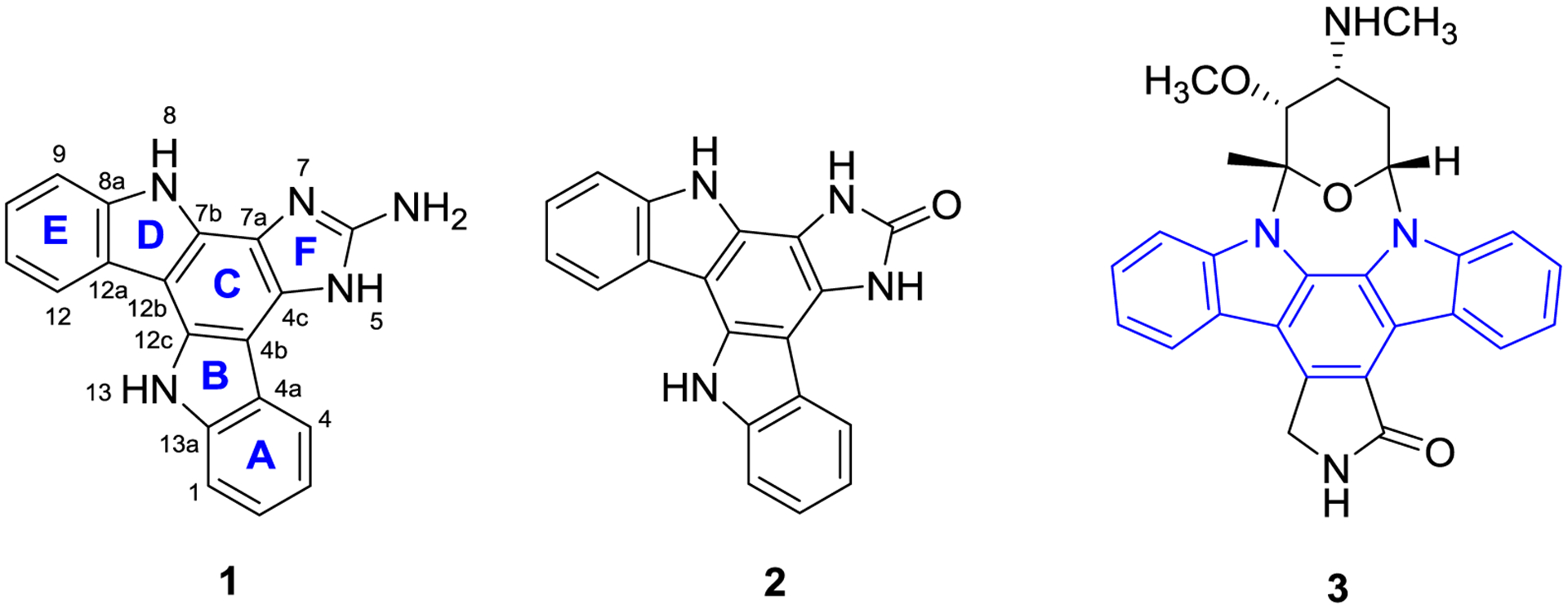

FIGURE 1.

Structures of damirines A (1) and B (2), and staurosporine (3)

FIGURE 3.

Key COSY, HMBC, LR-HSQMBC, and ROESY correlations for damirine B (2)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for permission of research operations in Thailand and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation for permission and organization of the sample collection. Grateful acknowledgement goes to the Natural Products Support Group (NCI at Frederick) for extract preparation. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E. This work utilized the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Omura S, Iwai Y, Hirano A, Nakagawa A, Awaya J, Tsuchiya H, Takahashi Y, Masuma R, J. Antibiot 1977, 30, 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nakano H, Ōmura S, J. Antibiot 2009, 62, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Janosik T, Wahlström N, Bergman J, Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 9159. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Janosik T, Rannug A, Rannug U, Wahlstrom N, Slatt J, Bergman J, Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 9058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stierle DB, Faulkner DJ, J. Nat. Prod 1991, 54, 1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) Tomlinson ML, J. Chem. Soc 1951, 809–811; [Google Scholar]; (b) Mann F, Willcox T, J. Chem. Soc 1958, 1525. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Meragelman KM, West LM, Northcote PT, Pannell LK, McKee TC, Boyd MR, J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Russell F, Harmody D, McCarthy PJ, Pomponi SA, Wright AE, J. Nat. Prod 2013, 76, 1989; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zheng X, Lv L, Lu S, Wang W, Li Z, Org. Lett 2014, 16, 5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liu D-Q, Mao S-C, Zhang H-Y, Yu X-Q, Feng M-T, Wang B, Feng L-H, Guo Y-W, Fitoterapia 2013, 91, 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Williamson RT, Buevich AV, Martin GE. Parella T , J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Henrich CJ, Budhu A, Yu Z, Evans JR, Goncharova EI, Ransom TT, Wang XW, McMahon JB, Chem. Biol. Drug Des B2013B, 82, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Some recent examples include:; (a) Chan STS, Nani RR, Schauer EA, Martin GE, Williamson RT, Saurí J, Buevich AV, Schafer WA, Joyce LA, Goey AKL, Figg WD, Ransom TT, Henrich CJ, McKee TC, Moser A, MacDonald SA, Khan S, McMahon JB, Schnermann MJ, Gustafson KR, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 10631; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Milanowski DJ, Oku N, Cartner LK, Bokesch HR, Williamson RT, Saurí J, Liu Y, Blinov KA, Ding Y, Li X-C, Ferreira D, Walker LA, Khan S, Davies-Coleman MT, Kelley JA, McMahon JB, Martin GE, Gustafson KR, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shoemaker RH, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Sankar E, Raju P, Karunakaran J, Mohanakrishnan AK, J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 13583; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kotha S, Saifuddin M, Aswar VR, Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14, 9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McCloud TG, Molecules 2010, 15, 4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sarotti AM, Pellegrinet SC, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 7254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A, J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 7512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].(a) Smith SG, Goodman JM, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 4597; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith SG, Goodman JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.