Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a comorbidity associated with heart failure and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Despite the Ca2+‐dependent nature of both of these pathologies, AF often responds to Na+ channel blockers. We investigated how targeting interdependent Na+/Ca2+ dysregulation might prevent focal activity and control AF.

Methods and Results

We studied AF in 2 models of Ca2+‐dependent disorders, a murine model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and a canine model of chronic tachypacing‐induced heart failure. Imaging studies revealed close association of neuronal‐type Na+ channels (nNav) with ryanodine receptors and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Catecholamine stimulation induced cellular and in vivo atrial arrhythmias in wild‐type mice only during pharmacological augmentation of nNav activity. In contrast, catecholamine stimulation alone was sufficient to elicit atrial arrhythmias in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia mice and failing canine atria. Importantly, these were abolished by acute nNav inhibition (tetrodotoxin or riluzole) implicating Na+/Ca2+ dysregulation in AF. These findings were then tested in 2 nonrandomized retrospective cohorts: an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinic and an academic medical center. Riluzole‐treated patients adjusted for baseline characteristics evidenced significantly lower incidence of arrhythmias including new‐onset AF, supporting the preclinical results.

Conclusions

These data suggest that nNaVs mediate Na+‐Ca2+ crosstalk within nanodomains containing Ca2+ release machinery and, thereby, contribute to AF triggers. Disruption of this mechanism by nNav inhibition can effectively prevent AF arising from diverse causes.

Keywords: atrial arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, cardiac arrhythmias, neuronal‐type Na+ channel blockade

Subject Categories: Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation, Basic Science Research, Calcium Cycling/Excitation-Contraction Coupling, Ion Channels/Membrane Transport

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CPVT

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- INa

Na+ current

- ISO

isoproterenol

- Nav

Na+ channel

- nNav

neuronal Na+ channel

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchange

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- WT

wild‐type

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Riluzole, a neuronal type Na+ channel blocker, was investigated in 2 retrospective amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cohorts.

Patients treated with riluzole had significantly lowered incidence of arrhythmias, including new‐onset atrial fibrillation.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The pharmacological class of neuronal‐type Na+ channel blockade may offer a unique mechanism to prevent arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation.

Atrial arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States.1 It is a common comorbidity associated with heart failure and its risk has been associated with “leaky” ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) Ca2+ release channels.2, 3, 4 The importance of leaky RyR2 to atrial arrhythmogenesis is particularly evident in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT).5 In this pathology, mutations in RyR2 or in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+‐binding protein calsequestrin increase propensity for AF.6 Emerging evidence also suggests that the link between Ca2+ handling and atrial arrhythmias is in part modulated by Na+ influx.7

The predominant Na+ channel (Nav) isoform found in the heart (Nav1.5) is decreased in cardiomyopathy, as well as in AF.7, 8 However, tetrodotoxin‐sensitive neuronal‐type Na+ channels (nNavs) are upregulated in these pathologies resulting in enhanced persistent Na+ current (INa).7, 9 The subcellular localization of different NaV isoforms thus determines the location of late Na+ entry relative to Ca2+‐handling machinery. This, in turn, may determine whether nNav‐mediated Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX) merely contributes to global cytosolic Ca2+ overload or acts directly to trigger abnormal Ca2+ release.10, 11, 12

Ventricular proarrhythmia is an important limitation of current drug therapies used in AF.13, 14, 15 Thus, the identification of agents that safely and effectively prevent arrhythmogenic trigger in the atria is imperative. Riluzole, an nNav inhibitor used to manage amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),16 effectively suppresses triggered ventricular arrhythmias in multiple animal models.10, 17, 18, 19 Given its extensive safety profile,20 riluzole could potentially safely prevent AF. Here, we provide evidence from preclinical models and patients suggesting riluzole as a safe and effective treatment for atrial arrhythmias.

Methods

Expanded methods are available in Data S1.

The preclinical and retrospective cohort data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author and Dr Mark Munger (mark.munger@hsc.utah.edu), respectively, upon reasonable request.

Study Approval

All animal procedures were approved by The Ohio State University and University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (publication No. 85‐23, revised 2011). The historical cohort was reviewed and approved as exempt following applicable guidelines involving the ethical treatment of human subjects by the University of Utah's institutional review board before the initiation of data collection. The University of Utah's institutional review board is fully accredited by the Human Research Protection Program.

Preclinical Evaluation of Antiarrhythmic Targeting of nNavs

Atrial cardiomyocytes, obtained from cardiac calsequestrin mutant (R33Q) wild‐type (WT) mice or failing canine hearts were enzymatically dissociated for patch‐clamp recordings, confocal immunolabeling, or Ca2+ imaging. A subset of mice was used to assess the role of nNavs in an in vivo arrhythmia induction.

Clinical Evaluation of Antiarrhythmic Targeting of nNavs

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with ALS who were treated with riluzole (study group) versus no riluzole (control group) from the ALS Centre of the Azienda Ospedaliero, Universitaria di Modena, Modena, Italy, and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. Data were collected through queries of structured data fields. Variables extracted from structured fields included demographic information (ie, age on the index date, sex, race, and body mass index), laboratory results, diagnostic tests and results, prescription records, and hospitalizations with cardiovascular encounter(s) including acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and any arrhythmia including atrial flutter or fibrillation. Race and ethnicity were grouped into white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and other/unknown. Cardiovascular risk factors and specific medications for cardiovascular risk prevention and treatment were collected and identified. Distribution of the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study cohort were described among the overall cohort from both the Italian and US databases, and among riluzole versus no‐riluzole users. Baseline characteristics between the riluzole and no‐riluzole groups were compared using chi‐square test, and Fisher exact test if the number of patients having a specific clinical character was <5. Cardiac pacemaker and implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator placement were collected, if applicable, and cardiac monitoring for AF was conducted based on patient presentation of symptoms.

The primary clinical end point was a composite of arrhythmia and AF. The time‐to‐end point from the first exposure to riluzole or earliest available date on or after the diagnosis of ALS, if no riluzole cohort, was projected using Kaplan–Meier curves where patients were censored when they encountered the end point or at the last follow‐up from each institution. The measure of treatment effect was hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI estimate from Cox proportional hazard regression model under intention‐to‐treat principles (ie, post‐index date variables were not incorporated into the analysis such as medication adherence) where the effect measure was adjusted for the baseline characteristics that were marginally different (P<0.1) between the riluzole and no‐riluzole groups. The analysis was performed for the overall cohort, then limited to the Utah cohort to qualitatively examine the influence of the heterogeneity across the Italy and US cohorts on the measure of treatment effect. All tests were 2‐tailed with an α of 0.05 for statistical significance. Data analysis was conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

nNav Blockade Prevents Leaky RyR2‐Induced Aberrant Ca2+ Oscillations

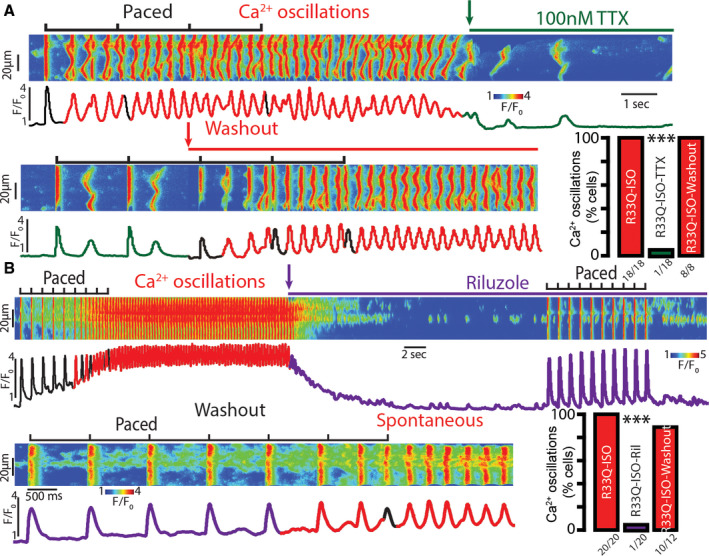

We first determined whether nNav exerts a unique action on intracellular Ca2+ handling, which may contribute to atrial arrhythmia initiation. Exposure of calsequestrin‐associated CPVT atrial myocytes to isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) induced self‐sustaining, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations, consistent with previous findings.6 These oscillations were abolished by tetrodotoxin (100 nmol/L; Figure 1A). Further, tetrodotoxin prevented induction of repetitive Ca2+ oscillations by field stimulation in the presence of isoproterenol in nearly all cells tested (Figure 1A), despite increasing SR Ca2+ load (Figure S1). However, field stimulation elicited Ca2+ oscillations in all cells upon washout of tetrodotoxin (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Inhibition of tetrodotoxin (TTX)‐sensitive neuronal NaVs (nNavs) is sufficient to prevent induction of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in R33Q atrial myocytes.

A, Representative examples of the line scan images and corresponding Ca2+ transients recorded in field‐stimulated R33Q atrial cardiomyocytes paced at 0.5 Hz and loaded with the Ca2+ indicator, Fluo‐3 AM. Cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 100 nmol/L) and subsequently TTX (100 nmol/L; green arrow indicates time when TTX was added) was rapidly applied. β‐Adrenergic stimulation with ISO promoted aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations (median pacing frequency was 2 Hz with the range of 0.5 to 4 Hz), while TTX (100 nmol/L) significantly decreased their incidence. Ca2+ oscillations were induced after drug washout (red arrow; number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, N=8 animals for ISO and ISO‐TTX, N=6 animals for ISO‐washout, respectively; ***P<0.0001 McNemar test for ISO vs ISO‐TTX, P<0.0001 Fisher exact test for ISO‐TTX vs ISO‐washout). B, Treatment of ISO (100 nmol/L)‐exposed R33Q atrial myocytes with 10 μmol/L riluzole (Ril) significantly reduced the incidence of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations, an effect that was washable (median pacing frequency was 2 Hz with the range of 0.5 to 7 Hz; number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, N=10 animals for ISO and ISO‐Ril, N=8 animals for ISO‐washout, respectively; ***P<0.0001 McNemar test for ISO vs ISO‐Ril, P<0.0001 Fisher exact test for ISO‐Ril vs ISO‐washout).

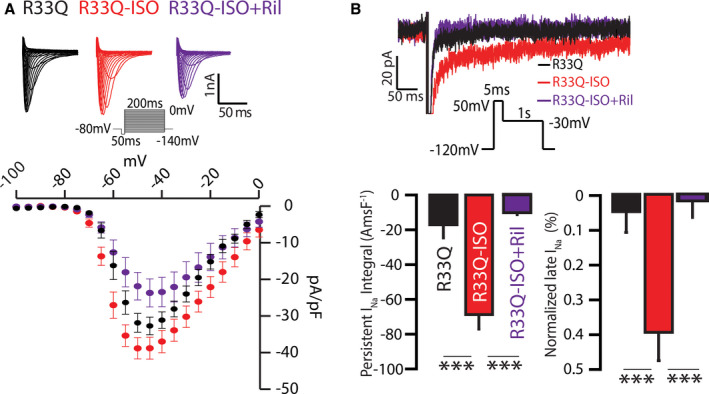

Next, we compared tetrodotoxin with riluzole, an agent currently employed in the management of ALS.21 At the resting potential, riluzole has been shown to preferentially block tetrodotoxin‐sensitive nNavs in dorsal root ganglion neurons.16 First, we examined the impact of riluzole on the tetrodotoxin‐sensitive component of INa. Both 100 nmol/L tetrodotoxin and 10 μmol/L riluzole reduced peak INa density to similar degrees (peak INa at −35 mV of −36.4±3.7 pA/pF versus −25.8±4.4 and −28.1±3.0 pA/pF for control, riluzole and tetrodotoxin, respectively; P=0.0002 Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test; Figure S2A). Both also shifted steady‐state inactivation of INa to more hyperpolarized potentials (V1/2 of −87.2±3.7 mV versus −98.1±3.0 and −95.9±3.2 mV for R33Q, riluzole and tetrodotoxin, respectively; P=0.0345 Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test; Figure S2B). Importantly, riluzole, like tetrodotoxin, prevented aberrant Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 1B) and increased SR Ca2+ load (Figure S1). These data point to the antiarrhythmic efficacy in CPVT of nNaV inhibition by riluzole, likely via suppression of late INa induced by isoproterenol. Under control conditions, we did not observe significant differences in late INa between WT and CPVT (Figures 2B and 5A). Upon addition of isoproterenol (100 nmol/L), CPVT atrial myocytes evidenced an increase in late INa (Figure 2B). Both peak as well as late INa were reduced by riluzole (Figure 2). Taken together, these data support a role for nNav in arrhythmogenic Ca2+ release in CPVT atria.

Figure 2. Effect of neuronal Nav (nNav) blockade with riluzole (Ril) on isoproterenol (ISO)‐promoted inward Na+ currents (INa) in R33Q atrial myocytes.

A, Representative INa (top) were elicited by a protocol presented in the inset before (black) or after addition of ISO (100 nmol/L; red) or ISO (100 nmol/L)+Ril (10 μmol/L; purple). (Bottom) Corresponding current‐voltage relationship from control, ISO, and ISO+Ril (n=10, 9, and 7 cells from 5, 6, and 5 mice, respectively). Addition of ISO+Ril reduced INa density relative to ISO alone (peak INa at −40 mV of −37.1±3.2 vs −22.4±3.9 pA/pF for ISO and ISO+Ril, respectively; P=0.0102 ANOVA, P=0.0418 for ISO vs ISO+Ril). B, Representative traces of persistent INa elicited using the protocol shown in the inset were recorded before (black) or after addition of ISO (100 nmol/L; red) or ISO+Ril (10 μmol/L; purple). ISO enhanced persistent INa in R33Q cardiomyocytes, while Ril suppressed β‐adrenergic–mediated increase in persistent INa (n=9, 8, and 8 cells from 3, 3, and 4 mice for R33Q, ISO, and ISO‐Ril, respectively; P<0.0001 ANOVA, ***P=0.0004 for persistent INa integral and ***P<0.0001 for normalized late INa). Summary data are presented as persistent INa integral Amp‐ms/F (AmsF−1; left) or normalized late INa (%; right), which were measured by either integrating INa between 50 and 450 ms (left) or normalizing mean persistent INa recorded between 250 and 450 ms by peak current generated by a step to ‐40 mV.

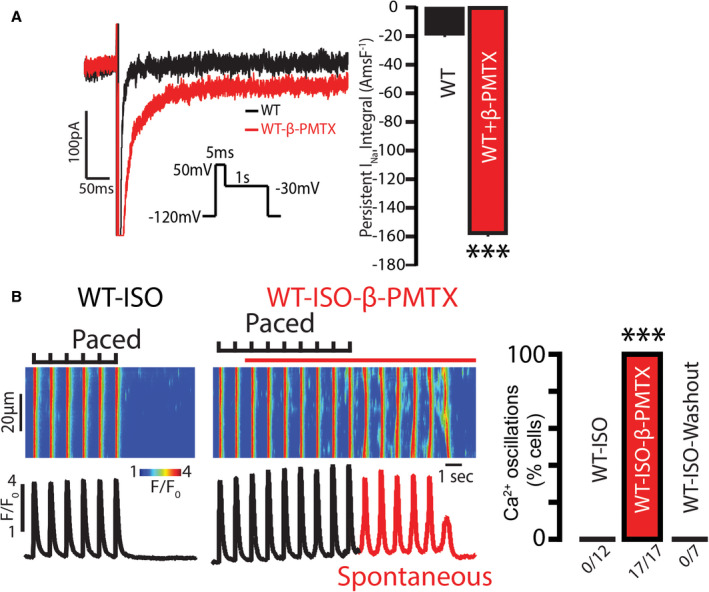

Figure 5. Augmentation of tetrodotoxin (TTX)‐sensitive neuronal Nav (nNav) is sufficient to initiate aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in wild‐type (WT) atrial myocytes.

A, Representative traces of persistent inward Na+ currents (INa) recorded in WT atrial cardiomyocytes before (black) and after (red) exposure to β‐pompilidotoxin (β‐PMTX; 40 μmol/L). β‐PMTX increased persistent INa relative to control (n=11 and 10 cells from 3 mice, respectively; ***P<0.0001 Wilcoxon rank sum test). B, (Left) Representative line scan images obtained from WT atrial cardiomyocytes exposed to isoproterenol (ISO; 100 nmol/L) and paced at 1 Hz. (Right) Rapid application of β‐PMTX (40 μmol/L) induced aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations. (Median pacing frequency was 0.5 Hz with the range of 0.5 to 2 Hz; number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, from N=3 mice; ***P<0.0001 Fisher exact test for ISO vs ISO–β‐PMTX, ***P<0.0001 Fisher exact test for ISO–β‐PMTX vs ISO‐washout).

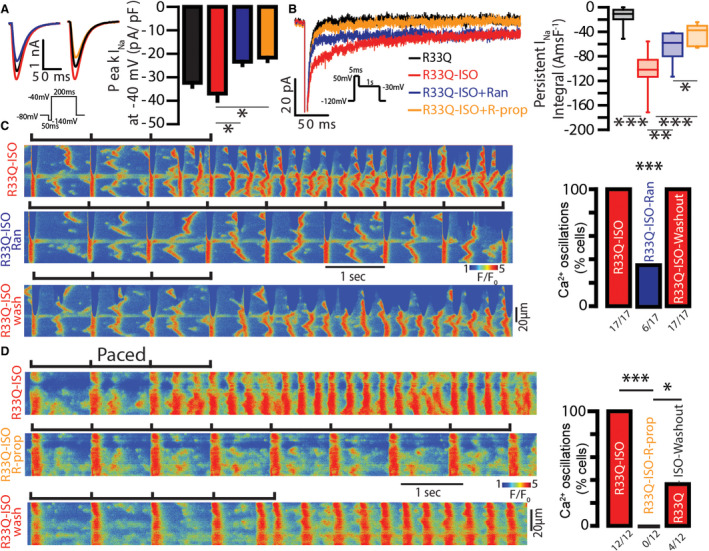

We also examined whether blockade of other NaV isoforms and/or RyR2 in addition to tetrodotoxin‐sensitive NaV isoforms confers additional benefit beyond that achieved with 100 nmol/L tetrodotoxin. To that end, we used R‐propafenone22, 23, 24, 25 (300 nmol/L) and ranolazine26, 27, 28, 29 (10 μmol/L) to assess their effect on cellular arrhythmia potential. At these concentrations, ranolazine and R‐propafenone achieved similar levels of peak INa reduction relative to riluzole (peak INa at −40 mV of −22.4±3.9 pA/pF versus −23.9±2.7 pA/pF and −23.3±1.5 pA/pF for isoproterenol+riluzole versus isoproterenol+ranolazine and isoproterenol+R‐propafenone, respectively; Figures 2A and 3A). Furthermore, both of these agents reduced induction of aberrant Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 3C and 3D). Notably, the extent of reduction in cellular arrhythmia propensity was proportional to the extent of late INa reduction achieved by these agents (Figure 3B), suggesting that nNav blockade is sufficient for the antiarrhythmic effect of NaV blockers. Furthermore, the effects of these 2 compounds were, in part, washable (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3. The extent of late inward Na+ currents (INa) inhibition corresponds to prevention of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in R33Q atrial myocytes.

A, (Left) INa obtained by step protocol illustrated in 1‐second intervals. (Right) In isoproterenol (ISO; 100 nmol/L)‐treated R33Q atrial myocytes, addition of ranolazine (Ran; 10 μmol/L, blue trace and bar; n=5 from N=4 animals) or R‐propafenone (R‐prop; 300 nmol/L, orange trace and bar; n=4 from N=3 animals) significantly reduced peak INa (P=0.0016 ANOVA, *P=0.0418 for ISO vs ISO+Ran and *P=0.0246 for ISO vs ISO+R‐prop) relative to ISO alone (n=7 from N=5 animals). Notably, there was no difference in peak INa reduction between the groups. B, (Left) Representative persistent INa elicited using the protocol shown in the inset. (Right) ISO (100 nmol/L) increased persistent INa, while Ran and R‐prop reduced it (n=13, 13, 7, and 7 cells from 6, 6, 6 and 4 mice for R33Q, ISO, ISO+Ran, and ISO+R‐prop, respectively; P<0.0001 ANOVA, ***P<0.0001, **P=0.0082, and *P=0.0480). Notably, R‐prop reduced ISO‐induced persistent INa to a greater extent than Ran (P=0.0480). C, Treatment of ISO (100 nmol/L)‐exposed R33Q atrial myocytes with Ran (10 μmol/L) significantly reduced the incidence of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations, which was washable (number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, N=5 animals; ***P=0.0009 McNemar test for ISO vs ISO‐Ran and for ISO‐Ran vs ISO‐washout). D, R‐prop abolished aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations, an effect that was only partially washable only after 10 minutes. (Number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, N=4 animals; ***P=0.0005 McNemar test for ISO vs ISO–R‐prop, *P=0.0455 for ISO–R‐propafenone vs ISO‐washout).

Next, we confirmed the importance of NCX to the proarrhythmic process in this model.6, 11 Acute NCX inhibition (5 mmol/L NiCl2) abolished repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in all cells tested (Figure S3A). Since we were unable to electrically stimulate cardiomyocytes in the presence of NiCl2, we repeated these experiments during NCX inhibition with SEA0400 (1 μmol/L). SEA0400 prevented induction of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ oscillations in over two thirds of cells tested (Figure S3B).

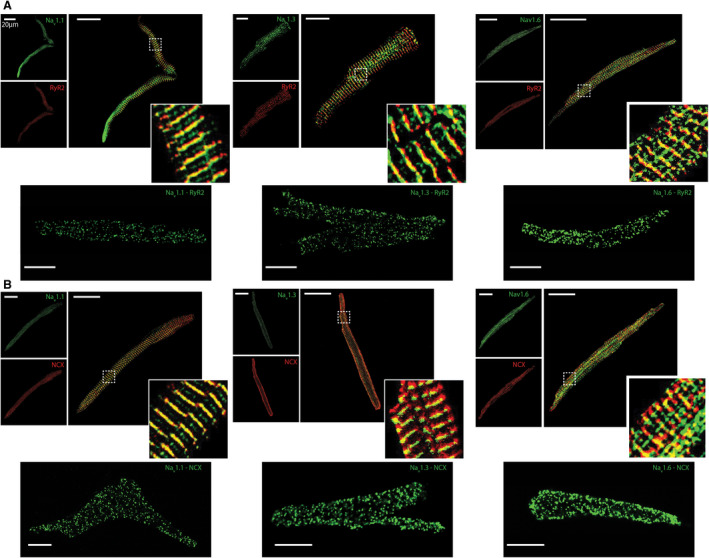

nNavs Closely Associate With Ca2+‐Handling Machinery

In order to examine close proximity of nNav with SR Ca2+‐release machinery, which may contribute to aberrant Ca2+ release through NCX in atrial myocytes, we performed confocal microscopy. This approach identified multiple nNav isoforms (Nav1.1, Nav1.3, and Nav1.6) localized near RyR2 and NCX in atrial myocytes from R33Q hearts (Figure 4A and 4B, top). Proximity ligation assays10 confirmed close association (within 40 nm)30 of all 3 nNav isoforms with RyR2 and NCX (Figure 4 and 4B, bottom). These results place nNavs near enough to leaky RyR2 to promote arrhythmias via aberrant NCX.

Figure 4. Neuronal Na+ channel (nNaV) and ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) colocalize to the same discrete subcellular regions.

Representative confocal micrographs of myocytes isolated from R33Q mice labeled for (A) RyR2 (red) and (B) Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX; red) with various Na+ channel (Nav) isoforms (Nav1.x, green). These often resulted in an overlap between the immunofluorescent signals (yellow) when overlaid. (Right) Close‐up views of regions highlighted by dashed white boxes. (Bottom) Representative fluorescent proximity ligation assay signal for RyR2 (A) and NCX (B) with different nNav isoforms (NaV1.x).

Augmentation of nNav Activity is Proarrhythmic

Next, we examined whether augmented nNav–mediated Na+ influx is sufficient to induce arrhythmogenic Ca2+ oscillations. Exposing WT myocytes to isoproterenol alone was insufficient to elicit Ca2+ oscillations. However, persistent INa induced by nNav augmentation (β‐pompilidotoxin, 40 μmol/L; Figure 5A)10, 31 promoted arrhythmogenic Ca2+ oscillations in WT cardiomyocytes exposed to isoproterenol (Figure 5B). This aberrant Ca2+ release resulted in a reduced SR Ca2+ load (Figure S4). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that enhanced nNav‐mediated Na+ influx is necessary as well as sufficient to produce proarrhythmic Ca2+ oscillations in WT atrial myocytes.

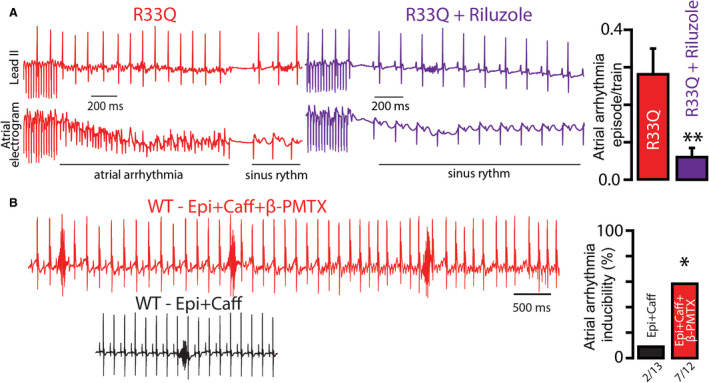

nNavs Modulate Atrial Arrhythmias in Mice

To determine the effects of nNav inhibition on atrial arrhythmias in mice with leaky RyR2,32 we treated them with riluzole (15 mg/kg IP).33 Atrial arrhythmia inducibility by atrial‐burst pacing was reduced by half following riluzole treatment (Figure 6A). In contrast, augmentation of nNav‐mediated Na+ influx by β‐pompilidotoxin (40 mg/kg IP) promoted atrial arrhythmias in WT mice: caffeine and epinephrine challenge induced atrial arrhythmias in 58% (7 of 12) of β‐pompilidotoxin–treated mice, compared with 15% (2 of 13) of untreated controls (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that perturbing local Na+‐Ca2+ crosstalk via modulation of nNav potently regulates atrial arrhythmia risk in vivo.

Figure 6. Modulation of tetrodotoxin (TTX)‐sensitive neuronal Nav (nNav) channel correspondingly modulates atrial arrhythmias in mice.

A, Simultaneous surface ECG (lead II) and intracardiac atrial electrograms with frequent, rapid P waves and irregular RR intervals suggestive of atrial arrhythmia such as atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation in R33Q mice after burst pacing. Pretreatment with riluzole (Ril; 15 mg/kg IP), targeting plasma concentrations of ~10 μmol/L,33 reduced the atrial arrhythmia inducibility (n=7 mice; **P=0.0160 Wilcoxon signed rank test). B, Representative surface ECG recordings of wild‐type (WT) mice treated (top, red ECG) or untreated (bottom, black ECG) with β‐pompilidotoxin (β‐PMTX; 40 mg/kg IP) and exposed to catecholamine challenge with epinephrine (Epi, 1.5 mg/kg) and caffeine (Caff, 120 mg/kg). Since increased heart rate has been linked to reduced arrhythmia inducibility in calsequestrin null mice, and WT mice show higher heart rate relative to calsequestrin null mice,32 all WT animals were pretreated with ivabradine (3 mg/kg) for 10 minutes before any intervention. Epi+Caff challenge during β‐PMTX exposure precipitated repetitive P waves and irregular RR intervals suggestive of atrial arrhythmia in over 50% of WT mice, which is a 3‐fold increase relative to β‐PMTX–untreated mice (number of mice tested and those positive for atrial arrhythmias depicted under the corresponding bars; *P=0.0410 Fisher exact test).

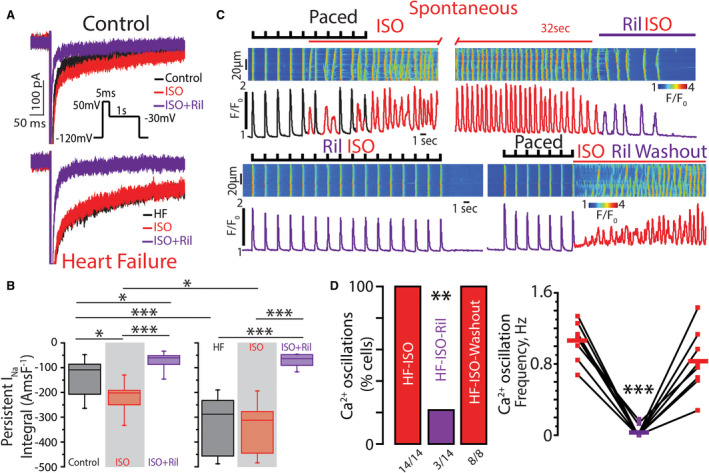

Targeting nNavs With Riluzole Prevents Arrhythmias in a Canine Cardiomyopathy Model

Next, we examined the contribution of nNavs to atrial arrhythmogenesis in a clinically relevant chronic tachypacing‐induced canine cardiomyopathy model (4 months of tachypacing).4 This model allowed us to test the relevance of nNav blockade with riluzole in a much more complex pathology that goes beyond leaky RyR2. Riluzole (10 μmol/L) reduced the integral of persistent INa in the presence of isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) in nonfailing atria by 66±4%. This is consistent with the previous observation that about half of late INa in nonfailing canine ventricles is carried by tetrodotoxin‐sensitive nNavs.34 Atrial myocytes isolated from cardiomyopathic canines evidenced enhanced persistent INa at baseline, relative to controls (Figure 7A and 7B). In contrast to controls, isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) did not further enhance persistent INa in failing atrial cells (Figure 7A and 7B). In the context of increased post‐translational modification of Ca2+ cycling proteins in this model,4 these results may point to increased post‐translational modification of Navs at baseline in failing hearts. Concurrently, proximity ligation assay revealed reduced incidence of NaV1.1 and NaV1.3 localizing in proximity to RyR2, while NaV1.6 localization in proximity to both RyR2 and NCX was significantly increased (Figure S5). Importantly, riluzole (10 μmol/L) reduced the integral of persistent INa in failing myocytes to the same level as in nonfailing atria (−67±9 versus −74±13 Amp.ms/F for failing and nonfailing atria, respectively; Figure 7A and 7B). Notably, enhanced persistent INa integral in failing atrial myocytes translated into aberrant Ca2+ cycling: all isoproterenol‐treated (100 nmol/L) failing atrial myocytes studied evidenced frequent, self‐sustaining Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 7C and 7D). Riluzole (10 μmol/L) significantly reduced these events, an effect that was reversed upon washout (Figure 7C and 7D). Taken together, these data suggest the translatability of targeting nNavs with riluzole in complex pathologies.

Figure 7. Riluzole (Ril) reduces enhanced, persistent inward Na+ currents (INa) and prevents induction of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in canine heart failure (HF) atrial myocytes.

A, Representative traces of persistent INa integral elicited using the protocol shown in the inset. Recordings were made in control (top) and failing (bottom) atrial myocytes before (black) and after exposure to isoproterenol (ISO; 100 nmol/L, red) and after treatment with Ril (10 μmol/L, purple). At baseline, atrial cardiomyocytes from failing hearts showed a larger persistent INa integral relative to control. ISO (100 nmol/L) enhanced persistent INa only in control cardiomyocytes. Ril reduced persistent INa integral in both control and failing atrial myocytes. B, Summary data are presented as persistent INa integral Amp‐ms/F (AmsF−1), which was measured by integrating INa between 50 and 450 ms (n=7 and 9 cells from 5 control and 3 failing dogs; P<0.0001 Kruskal–Wallis test; *P=0.0126 for control vs ISO, *P=0.0209 for control vs ISO+Ril, *P=0.0268 for control‐ISO vs HF‐ISO, ***P<0.0001). C, Representative examples of the line‐scan images and corresponding Ca2+ transients recorded in canine HF atrial cardiomyocytes loaded with Ca2+ indicator, Fluo‐3 AM, and paced at 0.5 Hz with field stimulation. (Top) Cells were treated with ISO (100 nmol/L) and subsequently Ril (10 μmol/L; purple bar indicates time when Ril was added) was rapidly applied. (Bottom) Resumption of field stimulation failed to induce Ca2+ oscillations during concomitant exposure to ISO and Ril; however, washout of Ril resulted in their reinitiation. D, Ril significantly reduced the incidence of aberrant, repetitive Ca2+ oscillations, an effect that was washable (median pacing frequency was 0.5 Hz with the range of 0.5 to 1 Hz; number of cells tested depicted under the corresponding bars, N=3 animals for ISO and ISO‐Ril, N=2 animals for ISO‐washout, respectively; **P=0.0009 McNemar test for ISO vs ISO‐Ril, P<0.0001 Fisher exact test for ISO‐Ril vs ISO‐washout incidence; ***P=0.0005 Friedman rank sum test for Ca2+ oscillations frequency).

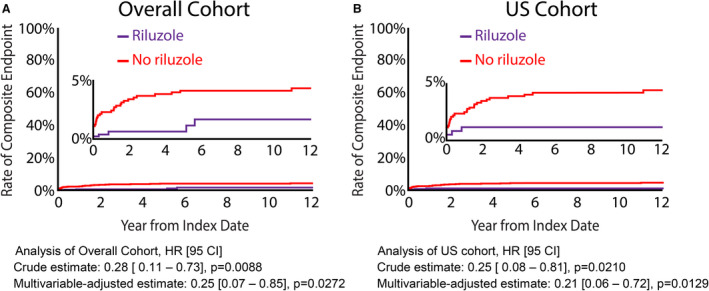

Targeting nNavs With Riluzole Controls New‐Onset AF in Patients With ALS

Based on the results from the canine model, we examined the effect of riluzole on atrial arrhythmias in human patients via a retrospective cohort study. The research cohort consisted of 184 Italian patients prescribed riluzole, 314 US patients prescribed riluzole, and 735 riluzole‐free patients from the United States (Table). Compared with the no‐riluzole patients, patients taking riluzole were age equivalent and had significantly more cardiovascular risk factors, more active disease, and more recorded cardiovascular events. In addition, the riluzole cohort were prescribed significantly more cardiovascular risk prevention and treatment medications, including β‐adrenergic blockers, Ca2+ channel blockers, aspirin, angiotensin system antagonists, and digitalis. The trends were consistent from both overall and US cohort analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Riluzole, % | No Riluzole, % | Riluzole vs No Riluzole P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy and United States (n=501) | United States (n=314) | United States (n=735) | Overall Cohort | United States | |

| Age ≥65 y | 44.6 | 40.4 | 43.7 | 0.7475 | 0.3331 |

| Concurrent conditions | |||||

| Hypertension | 25.5 | 14.0 | 7.2 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.9 | <0.0001 | 0.0072 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7.8 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 0.0481 | 0.2042 |

| AMI or ACS | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0036 | 0.1084 |

| Active smoking | 15.1 | 2.2 | 0.0 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CAD | 9.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | <0.0001 | 0.6344 |

| HF | 7.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | <0.0001 | 0.3644 |

| Stroke | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | <0.0001 | n/a |

| Current medication | |||||

| β‐Blocker | 6.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | <0.0001 | 0.1258 |

| CCB | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | <0.0001 | n/a |

| ASA | 20.0 | 15.6 | 5.7 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Statins | 12.8 | 10.8 | 3.0 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ACEI or ARB | 20.8 | 11.1 | 2.3 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Digitalis | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0146 | n/a |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetyl salicylic acid (aspirin); CAD, coronary artery disease (other than acute myocardial infarction [AMI] or acute coronary syndrome [ACS]); CCB, calcium channel blocker; HF, heart failure; and n/a, not applicable.

Patients with ALS treated with riluzole had significantly fewer overall cardiac arrhythmias. Five of 498 patients taking riluzole recorded tachyarrhythmia events versus 31 end points of 735 from the no‐riluzole cohort over the maximum follow‐up of 12 years, which resulted in the crude and adjusted HR of 0.28 (95% CI, 0.11–0.73; P=0.0088) and 0.25 (95% CI, 0.07–0.85; P=0.0272), respectively. The respective estimates when the analysis was limited to the US cohort were 0.25 (95% CI, 0.08–0.81; P=0.0210) and 0.21 (95% CI, 0.06–0.72; P=0.0129). The majority of arrhythmic events were distributed equivalently between supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia. The Kaplan–Meier curves of the arrhythmia events are presented in Figure 8, which reveals that arrhythmia events were reduced early and primarily throughout the first 2 years after riluzole prescribing. The majority of patients taking riluzole who recorded a tachyarrhythmia did not have cardiovascular disease. The rate of AF was lower in the rilozule group relative to the no‐riluzole group (P=0.0492). Specifically, AF occurred in 22 patients with ALS: 13 from Italy and 9 from the United States. One AF event was recorded after the riluzole prescription versus 9 events from the no‐riluzole cohort. Most patients who encountered AF had underlying cardiovascular disease (77%), with the majority treated with an angiotensin system antagonist; however, only 3 were treated with a β‐adrenergic blocker.

Figure 8. Riluzole prevents cardiac arrhythmias in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Two retrospective cohorts of ALS one exposed to riluzole vs no riluzole (controls), were compared by Cox proportional hazard models. The time‐to‐first composite arrhythmic events was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier production limit estimator. A, Overall cohort, (B) US cohort. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Riluzole safety was determined during the study period by recording any abnormal neutrophil count, or transaminase level (ie, alanine aminotransferase/serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase/serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, bilirubin, or gamma‐glutamyl transferase levels). There was no record of any abnormal laboratory value in the study cohort.

Discussion

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia.35 It is postulated that early use of rhythm control strategies may prevent arrhythmia progression.36 Current antiarrhythmic drugs such as flecainide or amiodarone are moderately beneficial in restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm but produce serious adverse effects such as ventricular tachycardia, negative inotropy, and extracardiac toxicity.37, 38 Therefore, there is a need for an effective and safe alternative to current antiarrhythmic therapy for AF. In this study, we have examined a nNav‐mediated mechanism for atrial arrhythmias in various preclinical models. These studies identify nNavs as a druggable target for safe and effective atrial arrhythmia prevention. To translate these results into a real‐world setting, we undertook a retrospective cohort study of patients with ALS. Riluzole‐treated patients with ALS had fewer AF and ventricular arrhythmias than those undergoing conventional ALS therapy without riluzole. Taken together, these findings suggest that riluzole merits serious consideration as treatment for atrial arrhythmias.

Role of nNavs in Atrial Arrhythmias

Here, we demonstrate for the first time that nNaVs play a key role in the development of atrial arrhythmias in the presence of genetic (murine‐CPVT; Figure 1) or acquired (canine‐heart failure; Figure 7) Ca2+ handling dysfunction.6, 39 nNav blockade effectively suppressed atrial arrhythmias on the cellular level as well as in vivo (Figure 6). Contrariwise, acute experimental augmentation of nNav function was sufficient to precipitate cellular arrhythmias in healthy atrial myocytes (Figure 5). Further, augmentation of nNav activity reduced SR Ca2+ load (Figure S4), while inhibition of these channels had the opposite effect (Figure S1). This argues against global SR Ca2+ overload being the mechanism underlying the observed arrhythmias. Of note, blockade of other NaV isoforms, including NaV1.5, with R‐propafenone22, 23, 24, 25 or ranolazine26, 27, 28, 29 in addition to nNaVs did not confer any apparent additional benefit beyond that achieved with 100 nmol/L of tetrodotoxin. This suggests that blockade of nNaVs is an important component of the antiarrhythmic mechanism of NaV blockers.

Our structural results point to the close proximity of nNavs to Ca2+‐handling machinery (RyR2 and NCX) as a potential factor underlying their privileged role in arrhythmogenesis (Figure 4 and Figure S5). In light of these findings, recent observations in patients with AF, which have revealed a reduction in Nav1.5 and upregulation of nNaVs,7 take on interesting implications. Mainly, remodeling within Na+/Ca2+ nanodomain, composed of nNaVs and Ca2+‐handling machinery (Figure S5), may potentially compensate for failing excitation‐contraction coupling. Inversely, the late INa carried by these channels (Figure 7A and 7B) and the consequent NCX, can facilitate aberrant Ca2+ release through sensitized leaky RyR2 (Figure 7C and 7D).40, 41 This is in line with other reports of increased nNaV and enhanced late INa in failing rat, canine, and human hearts.7, 9, 42 Hence, as proposed by our study, nNav blockade can be an effective antiarrhythmic strategy independent of remodeling within Na+/Ca2+ nanodomain or the pathogenesis of leaky RyR2.7, 10, 17, 18, 43 Furthermore, since ranolazine has been previously demonstrated to substantially affect multiple tetrodotoxin‐sensitive and ‐resistant NaV isoforms (NaV1.1, NaV1.4, NaV1.5, NaV1.7, and NaV1.8)26, 27, 28, 29 at concentrations that are achieved therapeutically (<10 μmol/L), tetrodotoxin‐sensitive nNaV blockade may, in part, be an explanation for the effectiveness of ranolazine in reducing late INa in failing human atria.7 However, despite our study pointing to nNavs as antiarrhythmia targets, future research will need to determine the specific Nav isoform, or the combination thereof, necessary for the antiarrhythmic effect of riluzole and other NaV blockers, such as ranolazine. Taken together, these results indicate a direct role for nNaV‐mediated Na+ influx in arrhythmia initiation, rather than it acting simply as a compounding factor.

Noteworthy, riluzole reduced persistent INa integral in nonfailing atria by 66±4%. This is consistent with previous observations that about half of late INa in canine ventricles is comprised of tetrodotoxin‐sensitive nNavs.34 Furthermore, riluzole reduced persistent INa by similar absolute extents in both failing and nonfailing atrial myocytes. This corresponded to a greater proportional impact on persistent INa integral in failing myocytes (78±3%) versus nonfailing myocytes (66±4%) as a result of enhanced persistent INa in failing atria. Together, these data indicate a role for nNaV remodeling within Ca2+‐handling nanodomains and increased post‐translational modification of NaVs in failing atria. This notion is consistent with findings in atria from patients with chronic AF, where an increase in nNaV isoforms accounted for increased late INa in AF.7 However, despite the aforementioned studies providing a parallel to our results, we cannot rule out the potential involvement of NaV1.5 in AF nor potential NaV1.5 inhibition by riluzole to the drug's antiarrhythmic mechanism.

Riluzole‐Treated Human Patients are Protected From AF

Whereas both tetrodotoxin and riluzole effectively suppressed atrial arrhythmias in animal models, concerns over toxicity render tetrodotoxin an untenable clinical option. In contrast, riluzole has a proven safety record as a treatment for ALS. In line with this, our data also suggest that riluzole was well tolerated. Hence, in our retrospective cohort study of arrhythmia risk among patients with ALS, riluzole‐treated patients with ALS had both fewer AF and ventricular tachycardia diagnoses compared with nontreated patients (Figure 8). To our knowledge, this is the first evidence to show that riluzole may have antiarrhythmic properties in humans. However, because of the nonrandomized nature of this study, further controlled studies are necessary to confirm and extend this finding. Given that ventricular proarrhythmia is a critical limitation of current AF drug therapies,13, 14, 15 riluzole and potentially other nNav inhibitors may provide an urgently needed safe alternative.

Limitations

A major limitation of small animal models is the translatability of findings into clinically relevant models of human disease. This factor is mitigated by our data demonstrating the antiarrhythmic efficacy of riluzole in a chronic tachypacing‐induced canine cardiomyopathy model. Riluzole can activate small‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels,44 which are upregulated in heart failure.45 While the possible contribution of this effect to riluzole's antiarrhythmic mechanism is not clear, our results with other NaV inhibitors suggest that it is not necessary. Whether small‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channel activation contributes to riluzole's antiarrhythmic effect will be an interesting subject for future study. Na+ channel blockers such as flecainide, R‐propafenone, or ranolazine can block RyR2, mitigating the impact of leaky RyR2.25, 29, 46 However, riluzole (10 μmol/L) did not affect Ca2+ sparks in permeabilized ventricular cardiomyocytes, a surrogate for RyR2 function.17 Even so, this mechanism merits further study. It is important to note that our retrospective cohort study of patients with ALS helps translate findings from animal models to humans. However, the study's observational and nonrandomized nature offers limited insight into the causality of observed effects. This limitation was mitigated, in part, by adjusting outcomes for baseline characteristics. Finally, outcomes were retrospectively obtained and were only available from existing data; therefore, we were not able to include any arrhythmia observations outside of the databases. Since other studies demonstrated similar incidence of arrhythmias,47 and valid results despite a similar limitation, we do not believe there would be differential ascertainment between the 2 cohorts.48 However, because of the unique character of the population (ie, ALS), further controlled studies are necessary to confirm and extend our findings.

Conclusions

We used experimental and preclinical animal models to delineate a mechanistically driven therapeutic strategy for atrial arrhythmias and provide evidence for its translational potential from a community‐based retrospective cohort. Specifically, we identify a nanodomain rich in nNaVs and Ca2+‐handling machinery (NCX and RyR2) that forms the basis of aberrant, self‐sustained Ca2+ release, resulting in atrial arrhythmias in vivo. Importantly, inhibition of nNavs with riluzole demonstrates efficacy in preventing atrial arrhythmias in both animal models and human patients. Thus, riluzole has the potential to be repurposed as a therapy for preventing AF.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL074045, HL063043 (to Györke), and HL127299 (to Radwański), as well as a Saving tiny Hearts grant and American Heart Association 19TPA34910191 (to Radwański).

Disclosures

Kim reports research grants from AstraZeneca, Myriad Genetics, and Pacira Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1 Figures S1–S5 References 49–51

Acknowledgments

Munger and Radwański provided conception/design of the work; Munger, Olğar, Koleske, Struckman, Mandrioli, Lou, Bonila, Kim, Ramos Mondragon, and Radwański performed research; Priori, Volpe, Biskupiak, Valdivia, and Carnes contributed tools; Olğar, Koleske, Struckman, Kim, Ramos Mondragon, Veeraraghavan, and Radwański analyzed data; and Munger, Veeraraghavan, Györke, and Radwański drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015119 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015119.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 12.

References

- 1. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Tsang TSM. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhuiyan ZA, van den Berg MP, van Tintelen JP, Bink‐Boelkens MT, Wiesfeld AC, Alders M, Postma AV, van Langen I, Mannens MM, Wilde AA. Expanding spectrum of human RYR2‐related disease: new electrocardiographic, structural, and genetic features. Circulation. 2007;116:1569–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lubitz SA, Benjamin EJ, Ellinor PT. Atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2010;6:187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Terentyeva R, Nishijima Y, Sridhar A, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA, Györke S. The relationship between arrhythmogenesis and impaired contractility in heart failure: role of altered ryanodine receptor function. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heijman J, Wehrens XH, Dobrev D. Atrial arrhythmogenesis in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia–is there a mechanistic link between sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) leak and re‐entry? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013;207:208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lou Q, Belevych AE, Radwański PB, Liu B, Kalyanasundaram A, Knollmann BC, Fedorov VV, Györke S. Alternating membrane potential/calcium interplay underlies repetitive focal activity in a genetic model of calcium‐dependent atrial arrhythmias. J Physiol. 2015;593:1443–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sossalla S, Kallmeyer B, Wagner S, Mazur M, Maurer U, Toischer K, Schmitto JD, Seipelt R, Schöndube FA, Hasenfuss G, et al. Altered Na(+) currents in atrial fibrillation effects of ranolazine on arrhythmias and contractility in human atrial myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2330–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zicha S, Maltsev VA, Nattel S, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Post‐transcriptional alterations in the expression of cardiac Na+ channel subunits in chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mishra S, Reznikov V, Maltsev VA, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Contribution of sodium channel neuronal isoform Nav1.1 to late sodium current in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. J Physiol. 2015;593:1409–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radwański PB, Ho HT, Veeraraghavan R, Brunello L, Liu B, Belevych AE, Unudurthi SD, Makara MA, Priori SG, Volpe P, et al. Neuronal Na+ channels are integral components of pro‐arrhythmic Na+/Ca2+ signaling nanodomain that promotes cardiac arrhythmias during β‐adrenergic stimulation. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2016;1:251–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radwański PB, Poelzing S. NCX is an important determinant for premature ventricular activity in a drug‐induced model of Andersen‐Tawil syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Radwański PB, Veeraraghavan R, Poelzing S. Cytosolic calcium accumulation and delayed repolarization associated with ventricular arrhythmias in a guinea pig model of Andersen‐Tawil syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starmer CF, Lastra AA, Nesterenko VV, Grant AO. Proarrhythmic response to sodium channel blockade. Theoretical model and numerical experiments. Circulation. 1991;84:1364–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hohnloser SH, Singh BN. Proarrhythmia with class III antiarrhythmic drugs: definition, electrophysiologic mechanisms, incidence, predisposing factors, and clinical implications. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:920–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song JH, Huang CS, Nagata K, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T. Differential action of riluzole on tetrodotoxin‐sensitive and tetrodotoxin‐resistant sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:707–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Radwański PB, Brunello L, Veeraraghavan R, Ho HT, Lou Q, Makara MA, Belevych AE, Anghelescu M, Priori SG, Volpe P, et al. Neuronal Na+ channel blockade suppresses arrhythmogenic diastolic Ca2+ release. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;106:143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koleske M, Bonilla I, Thomas J, Zaman N, Baine S, Knollmann BC, Veeraraghavan R, Györke S, Radwański PB. Tetrodotoxin‐sensitive Navs contribute to early and delayed afterdepolarizations in long QT arrhythmia models. J Gen Physiol. 2018;150:991–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weiss S, Benoist D, White E, Teng W, Saint DA. Riluzole protects against cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion damage via block of the persistent sodium current. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1072–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Debove C, Bejuit R, Truffinet P, Meininger V; ALS Study Groups I and II . Long‐term safety of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2002;3:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edrich T, Wang SY, Wang GK. State‐dependent block of human cardiac hNav1.5 sodium channels by propafenone. J Membr Biol. 2005;207:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Desaphy JF, Carbonara R, Costanza T, Conte Camerino D. Preclinical evaluation of marketed sodium channel blockers in a rat model of myotonia discloses promising antimyotonic drugs. Exp Neurol. 2014;255:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bang S, Yoo J, Gong X, Liu D, Han Q, Luo X, Chang W, Chen G, Im S‐T, Kim YH, et al. Differential Inhibition of Nav1.7 and neuropathic pain by hybridoma‐produced and recombinant monoclonal antibodies that target Nav1.7. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:22–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Faggioni M, Savio‐Galimberti E, Venkataraman R, Hwang HS, Kannankeril PJ, Darbar D, Knollmann BC. Suppression of spontaneous Ca elevations prevents atrial fibrillation in calsequestrin 2‐null hearts. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang GK, Calderon J, Wang SY. State‐ and use‐dependent block of muscle Nav1.4 and neuronal Nav1.7 voltage‐gated Na+ channel isoforms by ranolazine. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:940–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kahlig KM, Hirakawa R, Liu L, George AL, Belardinelli L, Rajamani S. Ranolazine reduces neuronal excitability by interacting with inactivated states of brain sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:162–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Block of tetrodotoxin‐sensitive, Na(V)1.7 and tetrodotoxin‐resistant, Na(V)1.8, Na+ channels by ranolazine. Channels (Austin). 2008;2:449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parikh A, Mantravadi R, Kozhevnikov D, Roche MA, Ye Y, Owen LJ, Puglisi JL, Abramson JJ, Salama G. Ranolazine stabilizes cardiac ryanodine receptors: a novel mechanism for the suppression of early afterdepolarization and Torsades de Pointes in long QT type 2. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rhett JM, Ongstad EL, Jourdan J, Gourdie RG. Cx43 associates with Na(v)1.5 in the cardiomyocyte perinexus. J Membr Biol. 2012;245:411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schiavon E, Stevens M, Zaharenko AJ, Konno K, Tytgat J, Wanke E. Voltage‐gated sodium channel isoform‐specific effects of pompilidotoxins. FEBS J. 2010;277:918–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Faggioni M, Hwang HS, van der Werf C, Nederend I, Kannankeril PJ, Wilde AA, Knollmann BC. Accelerated sinus rhythm prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and in patients. Circ Res. 2013;112:689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Milane A, Tortolano L, Fernandez C, Bensimon G, Meininger V, Farinotti R. Brain and plasma riluzole pharmacokinetics: effect of minocycline combination. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2009;12:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Biet M, Barajas‐Martínez H, Ton AT, Delabre JF, Morin N, Dumaine R. About half of the late sodium current in cardiac myocytes from dog ventricle is due to non‐cardiac‐type Na(+) channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH, Zheng ZJ, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Camm AJ, Dorian P, Hohnloser SH, Kowey PR, Tyl B, Ni Y, Vandzhura V, Maison‐Blanche P, de Melis M, Sanders P. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial assessing the efficacy of S66913 in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019;5:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tamargo J, Caballero R, Gómez R, Delpón E. I(Kur)/Kv1.5 channel blockers for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:399–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lau W, Newman D, Dorian P. Can antiarrhythmic agents be selected based on mechanism of action? Drugs. 2000;60:1315–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Glukhov AV, Kalyanasundaram A, Lou Q, Hage LT, Hansen BJ, Belevych AE, Mohler PJ, Knollmann BC, Periasamy M, Györke S, et al. Calsequestrin 2 deletion causes sinoatrial node dysfunction and atrial arrhythmias associated with altered sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling and degenerative fibrosis within the mouse atrial pacemaker complex. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:686–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radwański PB, Johnson CN, Györke S, Veeraraghavan R. Cardiac arrhythmias as manifestations of nanopathies: an emerging view. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Veeraraghavan R, Györke S, Radwański PB. Neuronal sodium channels: emerging components of the nano‐machinery of cardiac calcium cycling. J Physiol. 2017;595:3823–3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xi Y, Wu G, Yang L, Han K, Du Y, Wang T, Lei X, Bai X, Ma A. Increased late sodium currents are related to transcription of neuronal isoforms in a pressure‐overload model. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Radwański PB, Greer‐Short A, Poelzing S. Inhibition of Na+ channels ameliorates arrhythmias in a drug‐induced model of Andersen‐Tawil syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dimitriadi M, Kye MJ, Kalloo G, Yersak JM, Sahin M, Hart AC. The neuroprotective drug riluzole acts via small conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels to ameliorate defects in spinal muscular atrophy models. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6557–6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chang PC, Chen PS. SK channels and ventricular arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Watanabe H, Chopra N, Laver D, Hwang HS, Davies SS, Roach DE, Duff HJ, Roden DM, Wilde AA, Knollmann BC. Flecainide prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and humans. Nat Med. 2009;15:380–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, Murphy SA, Belardinelli L, Hedgepeth CM, Molhoek P, Verheugt FW, Gersh BJ, McCabe CH, et al. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency with Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST‐Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN‐TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007;116:1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mortensen EM, Halm EA, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA, Metersky M, Fine MJ, Johnson CS, Alvarez CA, Frei CR, Good C, et al. Association of azithromycin with mortality and cardiovascular events among older patients hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA. 2014;311:2199–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nishijima Y, Feldman DS, Bonagura JD, Ozkanlar Y, Jenkins PJ, Lacombe VA, Abraham WT, Hamlin RL, Carnes CA. Canine nonischemic left ventricular dysfunction: a model of chronic human cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2005;11:638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Belevych AE, Ho HT, Bonilla IM, Terentyeva R, Schober KE, Terentyev D, Carnes CA, Györke S. The role of spatial organization of Ca2+ release sites in the generation of arrhythmogenic diastolic Ca2+ release in myocytes from failing hearts. Basic Res Cardiol. 2017;112:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bao Y, Willis BC, Frasier CR, Lopez‐Santiago LF, Lin X, Ramos‐Mondragón R, Auerbach DS, Chen C, Wang Z, Anumonwo J, et al. Scn2b deletion in mice results in ventricular and atrial arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Figures S1–S5 References 49–51