Abstract

Background

Limited information exists regarding procedural success and clinical outcomes in patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). We sought to compare outcomes in patients undergoing PCI with or without CABG.

Methods and Results

This was an observational cohort study of 123 780 consecutive PCI procedures from the Pan‐London (UK) PCI registry from 2005 to 2015. The primary end point was all‐cause mortality at a median follow‐up of 3.0 years (interquartile range, 1.2–4.6 years). A total of 12 641(10.2%) patients had a history of previous CABG, of whom 29.3% (n=3703) underwent PCI to native vessels and 70.7% (n=8938) to bypass grafts. There were significant differences in the demographic, clinical, and procedural characteristics of these groups. The risk of mortality during follow‐up was significantly higher in patients with prior CABG (23.2%; P=0.0005) compared with patients with no prior CABG (12.1%) and was seen for patients who underwent either native vessel (20.1%) or bypass graft PCI (24.2%; P<0.0001). However, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, there was no significant difference in outcomes seen between the groups when PCI was performed in native vessels in patients with previous CABG (hazard ratio [HR],1.02; 95%CI, 0.77–1.34; P=0.89), but a significantly higher mortality was seen among patients with PCI to bypass grafts (HR,1.33; 95% CI, 1.03–1.71; P=0.026). This was seen after multivariate adjustment and propensity matching.

Conclusions

Patients with prior CABG were older with greater comorbidities and more complex procedural characteristics, but after adjustment for these differences, the clinical outcomes were similar to the patients undergoing PCI without prior CABG. In these patients, native‐vessel PCI was associated with better outcomes compared with the treatment of vein grafts.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention

Subject Categories: Catheter-Based Coronary and Valvular Interventions, Revascularization, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- BCIS

British Cardiovascular Intervention Society

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- LR

Log Rank

- MACE

major adverse cardiac event

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NHS

National Health Service

- NCDR

National Cardiovascular Data Registry

- NSTEMI

non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI

non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction

- TIMI

thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

As a result of disease progression, patients with prior coronary artery bypass grafting often require further revascularization because of recurrent symptoms of angina or presentation with acute coronary syndromes.

Limited information exists regarding procedural success and clinical outcomes in patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

This large observational study has shown that in patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting, native‐vessel percutaneous coronary intervention was associated with better outcomes compared with the percutaneous coronary intervention in vein grafts.

Patients with prior coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) often require further revascularization as a result of recurrent symptoms of angina or presentation with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This occurs because of the progression of atherosclerotic disease both in the native coronary arteries and particularly within saphenous vein grafts.1 It has previously been shown that up to 50% of vein grafts will have occluded or have a significant stenosis at 10 years.2, 3 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to saphenous vein grafts, although a recognized treatment strategy, is associated with higher rates of restenosis as well as procedural complications and longer term major adverse cardiac events (MACEs).4, 5, 6 Despite this, in recent studies, vein grafts have remained the target vessel for PCI in at least 25% of cases.7, 8

Limited information exists regarding procedural success and clinical outcomes in patients with previous CABG undergoing PCI. It is widely believed that technically feasible native coronary arteries should be the preferred target of PCI in this patient group because native coronary artery PCI appears to be associated with better short‐term and long‐term outcomes compared with bypass‐graft PCI, as suggested in guidelines.9 However, there are limited data to substantiate this belief, and it is mainly based on consensus opinion.7, 8, 10

In the present study, we report outcomes from a large cohort of consecutive patients undergoing PCI. Limited studies have compared outcomes after PCI in patients with and without previous CABG and in the latter, outcomes after PCI in native arteries against PCI to grafts. We therefore sought to describe the outcomes of PCI in patients with and without a history of prior CABG in a large unselected cohort from the Pan‐London Registry of the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS). Outcomes were compared with the population with no history of prior CABG undergoing PCI during the same study period.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article.

This was an observational cohort study of 123 780 consecutive PCI procedures from the Pan‐London (United Kingdom) PCI registry. This is a prospectively collected data set that includes all patients treated by PCI in London, United Kingdom, during a study period of January 2005 to December 2015. This includes all patients undergoing PCIs performed for stable angina and ACS (ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI], and unstable angina).

Pan‐London PCI Registry

The UK BCIS audit collects data from all hospitals in the United Kingdom that perform PCI, recording information about every procedure performed.11 The database is part of the suite of data sets collected under the auspices of the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research and is compliant with UK data protection legislation. The Pan‐London (United Kingdom) PCI registry includes all patients treated by PCI in the 9 PCI centers within the London, United Kingdom, area, which covers a population of 8.2 million. The 9 tertiary cardiac centers in London are Barts Heart Centre (Barts Health National Health Service [NHS] Trust), St Georges Hospital (St Georges Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust), Kings College Hospital (King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust), Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust), Hammersmith Hospital (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust), Guys & St. Thomas’ Hospital (St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Royal Free Hospital (Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust) and the Heart Hospital (University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). The registry included 123 780 patients who underwent PCI between 2005 and 2015. We merged the anonymized databases of the 9 London centers that collect data based on the BCIS data set. The BCIS audit is part of a national mandatory audit in which all UK PCI centers participate. PCI is defined as the use of any coronary device to approach, probe, or cross 1 or more coronary lesions with the intention of performing a coronary intervention.11 Data are collected prospectively at each hospital, electronically encrypted, and transferred online to a central database. Every patient entry offers details of the patient journey, including the method and timing of admission, inpatient investigations, results, treatment, and outcomes. Patients’ survival data are obtained by the linkage of patients’ NHS numbers to the Office of National Statistics, which records live/death status and the date of death for all deceased patients. Patient and procedural details were recorded at the time of the procedure and during the admission into each center's local BCIS database. Anonymous data sets with linked mortality data from the Office of National Statistics were merged for analysis from the 9 centers.

Study Population and Procedures

Patient demographic characteristics were collected, including age, smoking status, left ventricular function, previous myocardial infarction (MI), previous revascularization (PCI and CABG), indications for PCI, and New York Heart Association classification as well as the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiogenic shock, hypercholesterolemia, peripheral vascular disease, preprocedural cardiac arrest and chronic kidney disease (defined as creatinine>200 or renal replacement therapy). The technical aspects of the PCI procedure were also recorded as well as adverse outcomes, including complications up to the time of hospital discharge. Patients undergoing PCI were loaded with antiplatelet drugs prior to their procedures (clopidogrel [300–600 mg] and aspirin [300 mg]). The clopidogrel was typically continued for 1 month postimplantation of a bare‐metal stent or 1 year if drug‐eluting stent implantation occurred or if the procedure was performed for an MI. The use of adjunctive pharmacology (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, bivalirudin, heparin, and thrombolysis) was left to the discretion of the interventional cardiologist performing the procedure. Coronary artery disease was classified by severity of luminal narrowing (0%, 1%–49%, 50%–74%, 75%–94%, 95%–99%, or 100%) and by vessel effected (eg, left anterior descending).

Clinical Outcomes

The primary clinical outcome was all‐cause mortality, with data obtained from the UK Office for National Statistics. Secondary outcomes were in‐hospital MACE defined as a composite of all‐cause mortality, PCI‐related MI (new ischemic pain with new ST elevation and elevation of enzymes whether treated with further revascularization therapy), stroke and reintervention PCI. Non‐MACE complications included arterial complications, aortic dissection, coronary dissection (dissection defined as unintentional intimal disruption using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute classification system for intimal tears12 and coronary perforation). We hypothesized that adverse clinical outcomes in patients with previous CABG are driven by baseline comorbidities and the treatment of VGs (vein grafts) rather than native coronary artery disease. Therefore, we also hypothesized that the outcome of native‐vessel PCI in previous CABG is no different from patients without prior CABG.

Ethics

The data collected were part of a mandatory national cardiac audit, and all patient‐identifiable fields were removed prior to merging the data sets and analysis. The local ethics committee advised that formal ethical approval was not required for this study.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of statistical analysis, the study population was divided into the following 3 groups: (1) no previous CABG, (2) prior CABG with PCI to native coronary arteries, and (3) prior CABG with PCI to bypass grafts. The characteristics of patients were compared across the 3 groups. These comparisons were performed using Fisher's exact tests for binary/categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro‐Wilks test. We calculated Kaplan‐Meier product limits for cumulative probability of reaching an end point and used the log‐rank test for evidence of a statistically significant difference between the groups. In the case of missing data (except for left ventricular ejection fraction), unknown values were imputed to the most common categorical variable and to the median or subgroup‐specific median of continuous variables. Time was measured from the index admission to outcome (all‐cause mortality).

Cox regression analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios for the effect of previous CABG in age‐adjusted and fully adjusted models based on covariates (P<0.05) associated with the outcome. A number of covariates were included in the model, including age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, previous PCI, previous MI, chronic renal failure, preprocedure thrombolysis in MI (TIMI) flow, year of study, procedural success, left main stem intervention, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIA use. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by examining log (‐log) survival curves and additionally was tested with Schoenfield's residuals. The proportional hazard assumption was satisfied for all outcomes evaluated. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of including or excluding ejection fraction or previous PCI to the multivariate model. Normality was confirmed for all variables, and therefore we conducted ANOVA for all analyses.

A propensity score analysis was carried out using a nonparsimonious logistic regression model comparing previous CABG and no CABG and previous bypass‐graft versus native‐vessel intervention. Multiple variables were included in the model, including age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, previous PCI, previous MI, chronic renal failure, preprocedure TIMI flow, procedural success, left main stem intervention, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIA use. After ranking propensity score in an ascending order, a nearest‐neighbor 1:1 matching algorithm was used with callipers of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Each CABG and no CABG and previous bypass‐graft versus native‐vessel intervention was used in at most 1 matched pair to create a matched sample with a similar distribution of baseline characteristics between the observed groups. Based on the matched samples, the Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the association of complete revascularization on mortality over follow‐up. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

There were 123 780 PCI procedures performed during the study period. The patient demographics and risk factor profiles were as expected for an unselected PCI registry (Table 1). Patients had a mean age of 64.3±12.1 years and 25.2% were women; 22.4% of the patients were diabetic, and 27.3% had a history of previous MI.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Split Into Patients With and Without Previous CABG

| PCI to Native, No CABG (n=111 139) | PCI to Native in CABG (n=3703) | PCI to Grafts (n=8938) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.72±12.39 | 69.83±9.41 | 67.76±10.17 | <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity, white | 4845 (43.5) | 1352 (36.5) | 4183 (46.8) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, male | 82 576 (74.3) | 3025 (81.7) | 2472 (87.1) | <0.0001 |

| Previous MI | 29 785 (26.8) | 2414 (65.2) | 5202 (58.2) | <0.0001 |

| Previous PCI | 26 896 (24.2) | 1689 (45.6) | 4308 (48.2) | <0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 78 353 (70.5) | 2588 (69.9) | 6355 (71.1) | 0.108 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24 895 (22.4) | 1359 (36.7) | 3155 (35.3) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 60 904 (54.8) | 2540 (68.6) | 6114 (68.4) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking history | 66 572 (59.9) | 2244 (60.6) | 6239 (59.8) | 0.084 |

| PVD | 3112 (2.8) | 185 (5.0) | 572 (6.4) | <0.0001 |

| CKD (creatinine>200) | 445 (4.0) | 259 (7.0) | 742 (8.3) | <0.0001 |

| Previous CVA | 111 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 18 (0.2) | 0.220 |

| Poor LV function | 8447 (7.6) | 430 (11.6) | 920 (10.3) | <0.0001 |

| Presentation | ||||

| STEMI | 29 785(26.8) | 378 (10.2) | 1282 (14.3) | <0.0001 |

| NSTEMI | 33 897 (30.5) | 1141 (30.8) | 3048 (34.1) | <0.0001 |

| Elective | 47 456 (42.7) | 2185 (59.0) | 4612 (51.6) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 3112 (2.8) | 67 (1.8) | 143 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

Data are mean±SD or number (percentage). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; MV, multivessel; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; and STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

A total of 12 641 (10.2%) of the patients had a history of prior CABG, and 111 139 of the patients had no prior history of CABG (268 patients with previous CABG who underwent treatment of graft and native vessel were excluded). In patients with previous CABG, 3703 (29.3%) underwent the treatment of a native coronary artery compared with 8938 (70.7%) who underwent bypass‐graft treatment. The proportion of PCIs performed in patients with previous CABG increased over time (10.5%–15.3%). During the study period, there was a reduction in the treatment of bypass grafts: 6.6% in 2006 to 5.7% in 2015 (P=0.03) compared with native PCI, which increased over time (4.2%–6.1%).

Baseline and Procedural Characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were significant differences in the demographic, clinical, and procedural characteristics of the 3 groups. Patients with previous CABG were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease cerebrovascular disease, and previous MI/percutaneous revascularization (PCI).

Patients without previous CABG were more likely to undergo the procedure via the radial route followed by native‐vessel treatment in previous CABG, with the lowest radial access rates seen in vein‐graft PCI. Higher rates of chronic total occlusion intervention, intravascular ultrasound, and drug‐eluting stent use were seen in native versus graft PCI (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, lower baseline TIMI flow grade, ACS presentation, male sex, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, and the presence of a chronic total occlusion were associated with a higher likelihood of graft versus native coronary artery PCI. The rates of chronic total occlusion intervention varied across patient presentations and were reported as being the treated vessel in 38.1% of elective cases, 19.3% in NSTEMI cases, and 4.6% in STEMI cases; consequently, the rates of VG PCI also varied across treatment groups with opposite trends (3.2% versus 25.8% versus 39.7%).

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics Split Into Patients With and Without Previous CABG

| PCI to Native, No CABG (n=111 139) | PCI to Native in CABG (n=3703) | PCI to Grafts (n=8938) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access for PCI | ||||

| Radial | 36 898 (33.2) | 781 (21.1) | 903 (10.1) | <0.0001 |

| Vessel treated | <0.0001 | |||

| Left main | 2890 (2.6) | 1126 (30.4) | 0 (0) | |

| LAD | 58 015 (52.2) | 3355 (90.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Left circumflex | 27 340 (24.6) | 1259 (34.0) | 0 (0) | |

| RCA | 42 455 (38.3) | 1074 (29.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Grafts | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8938 (100) | |

| CTOs | 9336 (12.4) | 1056 (28.6) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Multivessel PCI | 23 673 (21.3) | 618 (16.7) | 1207 (13.5) | 0.018 |

| Mean stent number | 1.55±1.15 | 1.53±1.20 | 1.55±1.13 | 0.012 |

| Lesion diameter, mm | 3.18±2.10 | 3.20±2.78 | 3.94±3.58 | <0.0001 |

| Lesion length, mm | 22.68±13.80 | 22.91±15.59 | 21.73±11.81 | 0.182 |

| Distal protection device | 222 (0.2) | 41 (1.1) | 1394 (15.6) | <0.0001 |

| IVUS use | 5001(4.5) | 178 (4.8) | 268 (3.0) | <0.0001 |

| DES use | 101 692 (91.5) | 3485 (94.1) | 7588 (84.9) | <0.0001 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 27 118 (24.4) | 1215 (32.8) | 4219 (47.2) | <0.0001 |

| Procedural success | 102 470 (92.2) | 3403 (91.9) | 8017 (89.7) | 0.002 |

Data are mean±SD or number (percentage). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CTO, chronic total occlusion; DES, drug‐eluting stent; GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and RCA, right coronary artery.

Clinical Outcomes

In‐Hospital Outcomes

Procedural and vascular complication rates were generally low but were higher in patients undergoing vein‐graft PCI compared with the other groups, particularly rates of no reflow (P=0.002). However, bleeding complications were similar across all 3 groups: 0.7% (no CABG) versus 0.6% (native vessel) versus 0.7% (graft PCI). In‐hospital event rates were similar across all 3 groups: 4.0% (no CABG) versus 4.3% (native vessel) versus 3.7% (graft PCI) for MACE, and 1.5% versus 1.3% versus 1.6%, respectively, for mortality.

All‐Cause Mortality

Previous CABG

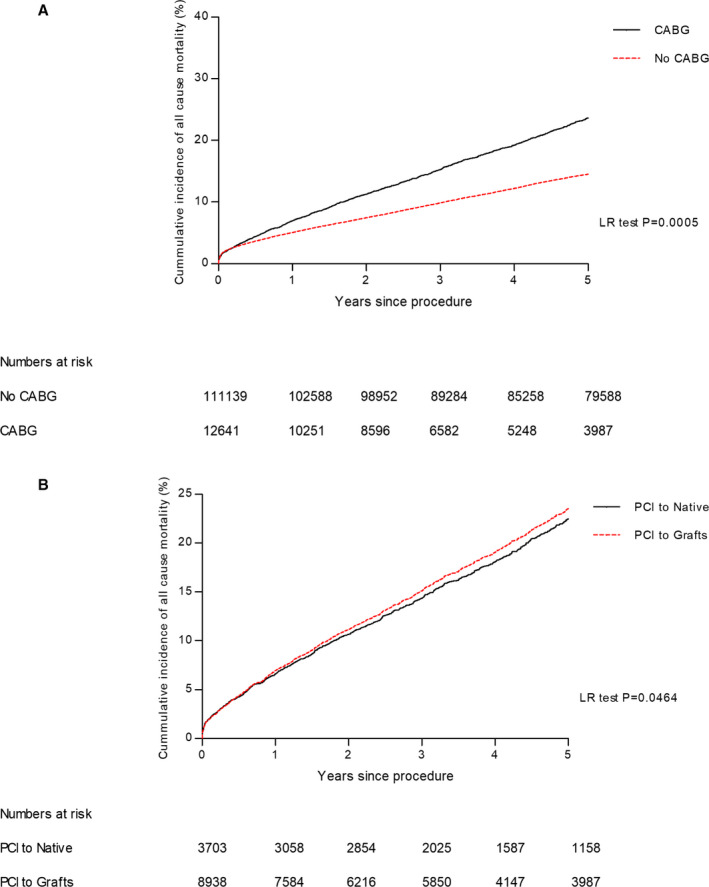

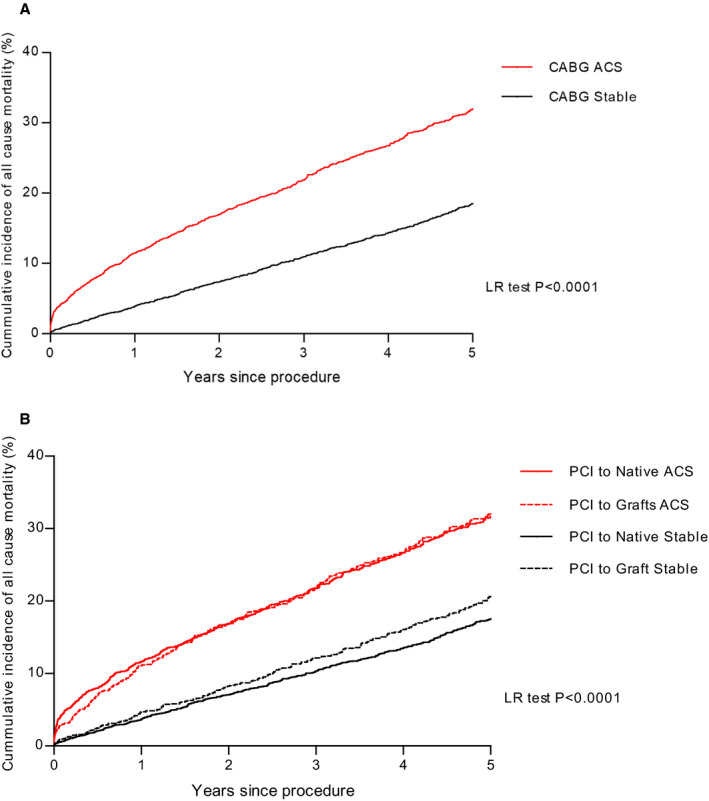

A significant unadjusted difference in mortality was observed between patients with no history of prior CABG (12.1%) compared with patients with prior CABG (23.2%) (P=0.0005) and was seen for patients who underwent either native‐vessel (20.1%) or bypass‐graft PCI (24.2%; P<0.0001; Figure 1. Higher rates of mortality were seen dependent on PCI indication, with higher rates in ACS compared with stable in patients with prior CABG (P<0.0001; Figure 2A).

Figure 1. Kaplan‐Meier curves showing cumulative probability of all‐cause mortality after PCI according to group: (A) PCI in patients who have had CABG vs no CABG and (B) PCI to native vs grafts.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; LR, Log Rank; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 2. Kaplan‐Meier curves showing cumulative probability of all‐cause mortality after PCI according to presentation: (A) PCI in patients who have had coronary artery bypass grafting (acute coronary syndrome vs stable) and (B) PCI to native vs grafts in acute coronary syndrome vs stable.

ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; LR, Log Rank; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

In the unadjusted univariate analysis, the risk of mortality during follow‐up was significantly higher in patients with previous CABG (hazard ratio [HR], 2.11; 95% CI, 1.40–2.97; P=0.007) compared with patients without CABG. However, after adjustments for baseline covariates, there was no association between previous CABG and outcome (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.85–1.74; P=0.59; Table 3). Variables showing an independent association with mortality were age, cardiogenic shock, chronic renal failure, and severe systolic left ventricular impairment. Radial artery access and procedural success were also independently associated with survival.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Model of Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Mortality in the Whole Population

| Variable | Comparator | Univariate | Multivariable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age | 1.08 (1.07–1.08) | 1.07 (1.06–1.08) |

| Male | Female | 1.30 (1.26–1.35) | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| Ethnicity (Asian) | White | 1.18 (1.15–1.22) | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) |

| Cardiogenic shock | No cardiogenic shock | 4.64 (4.33–4.98) | 3.77 (3.25–4.36) |

| Diabetic | Nondiabetic | 1.53 (1.47–1.59) | 1.47 (1.34–1.62) |

| Previous MI | No previous MI | 1.49 (1.44–1.55) | 1.26 (1.14–1.40) |

| Previous PCI | No previous PCI | 1.06 (1.07–1.15) | 1.02 (0.91–1.14) |

| Hypertension | No hypertension | 1.40 (1.35–1.45) | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | No hypercholesterolaemia | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

| eGFR<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | eGFR>60 | 4.22 (4.00–4.46) | 2.44 (2.10–2.84) |

| EF<35% | EF>35% | 2.18 (2.04–2.33) | 1.75 (1.54–1.98) |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use | No GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use | 0.91 (0.87–0.94) | 0.94 (0.83–1.26) |

| Procedural success | Procedural failure | 0.63 (0.58–0.67) | 0.72 (0.62–0.82) |

| Access route (radial) | Femoral | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 0.93 (0.87–0.96) |

| Previous CABG | No previous CABG | 2.67 (1.40–2.97) | 1.26 (0.85–1.74) |

The overall sample size included 98.5% of the patients in this analysis. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; MI, myocardial infarction; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Native Versus Graft PCI

In the unadjusted univariate analysis, the risk of mortality during follow‐up was significantly higher in patients undergoing PCI to a bypass graft (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.08–1.81; P=0.003) and PCI undertaken in native coronary arteries in patients with previous CABG (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10–1.67; P=0.007) compared with PCI in native coronary arteries. Interestingly, when assessing by indication for PCI, no difference between PCI to a native vessel and PCI to a VG was seen in patients presenting with ACS; however, significant differences exist between the 2 groups in stable coronary artery disease (P<0.0001; Figure 2B).

After adjustments for baseline covariates, there was no significant difference in outcomes for PCI in native vessels in patients with CABG (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.77–1.34; P=0.89), but a significantly higher mortality among patients with PCI to bypass grafts (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.03–1.71; P=0.026; Table 4). The aforementioned Cox proportional hazard model was repeated with the year of procedure included as a categorical variable to allow for improvements in PCI technique and technology during the long study period. This confirmed the associations between bypass‐graft PCI (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.08–1.83; P=0.0004) and mortality, with no difference seen between the native‐vessel PCI in previous CABG and native‐vessel treatment with no previous bypass (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.62–1.26; P=0.45).

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Model of Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Previous CABG

| Variable | Comparator | Univariate | Multivariable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age | 1.06 (1.06–1.07) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) |

| Male | Female | 1.18 (1.06–1.32) | 1.05 (0.87–1.28) |

| Ethnicity (Asian) | White | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | 1.33 (1.14–1.55) |

| Cardiogenic shock | No cardiogenic shock | 5.56 (4.40–7.04) | 4.31 (2.91–6.37) |

| Diabetic | Nondiabetic | 1.28 (1.17–1.40) | 1.36 (1.17–1.58) |

| Previous MI | No previous MI | 1.45 (1.32–1.60) | 1.30 (1.10–1.52) |

| Previous PCI | No previous PCI | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 1.05 (0.92–1.16) |

| Hypertension | No hypertension | 1.16 (1.05–1.28) | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | No hypercholesterolaemia | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 1.26 (1.06–1.49) |

| eGFR<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | eGFR>60 | 3.19 (2.81–3.62) | 2.12 (1.70–2.65) |

| EF<35% | EF>35% | 2.19 (1.87–2.57) | 1.74 (1.43–2.11) |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use | No GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor use | 0.94 (0.80–1.04) | 0.96 (0.83–1.26) |

| Procedural success | Procedural failure | 0.83 (0.67–1.03) | 0.76 (0.60–0.89) |

| Access route (radial) | Femoral | 0.97 (0.87–1.13) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) |

| Bypass‐graft intervention | Native‐vessel intervention | 1.38, 95% (1.08–1.81) | 1.33 (1.03–1.71) |

The overall sample size included 97.3% of the patients in this analysis. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; EF, ejection fraction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; MI, myocardial infarction; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Clinical Outcomes in the Propensity‐Matched Populations

Two propensity‐matched cohorts were assessed: prior CABG versus no prior CABG (24 200 patients, 12 100 patients in each group) and bypass‐graft versus native‐vessel PCI in patients with previous bypass (7302 patients, 3651 in each group). The baseline demographics and procedural variables were well balanced in each of the propensity‐matched cohorts, with the minimal P value after matching comparing the variables between the 2 groups being P>0.40 in all matched groups.

All‐Cause Mortality

No differences in outcomes between patients with or without previous CABG were seen after propensity matching in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses. However, when comparing patients with previous CABG where PCI was performed in either the native vessel or the graft, a significant association with mortality was seen with graft PCI (13.6% versus 23.8%; P<0.0001). When applying Cox multivariate regression analysis to adjust for baseline clinical and procedural characteristics, native‐vessel PCI was an independent predictor for reduced mortality (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.21–0.87; P=0.0008) compared with graft PCI, but not when compared with native‐vessel PCI (no prior CABG; HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.51–1.48; P=0.53).

DISCUSSION

The results in this study encompass outcomes for one of the largest groups of consecutive patients with and without prior CABG undergoing PCI for stable coronary syndromes and ACSs, specifically comparing the outcomes of patients with and without CABG and treatment to both native coronary arteries and bypass grafts. We have shown that significantly higher mortality rates are associated with prior CABG, but these are corrected for by an adjustment for comorbidities. Interestingly, among patients with previous CABG who underwent PCI to a bypass graft, higher mortality rates were seen compared with if a native vessel was treated, whereas no difference was seen with native‐vessel treatment when compared with patients without prior CABG. This adds further evidence to support the concept that a native vessel should be treated if possible when performing secondary revascularization in this group of patients postsurgery.13 It is also worth emphasizing that although in‐hospital event rates, including death, were comparable across all 3 study groups, the patients who had PCI to a bypass graft had significantly elevated mortality after discharge over time, even when the baseline characteristics had been corrected for. The reassurance of a technically successful PCI to a bypass graft is not necessarily a strong predictor of good long‐term outcome.

Although there are data to support that PCI in these patients should be performed to native vessels where possible,13 >70% of patients in our data set with prior CABG underwent PCI to a bypass graft. Although in keeping with other analyses from the United Kingdom,10 albeit a primary PCI cohort, this is a much higher proportion of patients than seen in other similar studies. A series of studies from the United States has shown rates of bypass‐graft intervention of around 43% both in 200214 and more recently in 2009. The largest study by Brilakis et al8 looked at 300 902 patients with prior CABG from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) CathPCI Registry demonstrated the target vessel for PCI was a bypass graft in only 37.5% of their patients. This may reflect the fact that 43% of their study cohort were >10 years post CABG at the time of PCI, which is known to influence decision making; however, further study is needed to understand these differences. It is likely that anatomy rather than clinician choice may drive this decision, and whether native options were available when a bypass graft was treated is unknown and warrants further study.

The type of presentation appears to have an impact on the target lesion. In our study, patients presenting with STEMI after prior CABG accounted for a greater proportion of bypass‐graft PCI than native‐vessel PCI (15.2% versus 9.6%; P<0.0001), whereas patients presenting with stable symptoms after prior CABG accounted for 61% of PCI to native vessels versus 46% of PCI to bypass grafts (P<0.0001). This is similar to other studies that have identified that patients with prior CABG who received PCI to a native vessel were more likely to present with stable angina rather than an ACS.14, 15Other factors aside from clinical presentation that were associated with a higher likelihood of graft PCI in our study included male sex, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, and lower baseline TIMI flow grade. These are similar factors as those described by Brilakis et al8 They also reported that saphenous vein‐graft PCI constituted an increasing proportion of PCI as time from CABG lengthened, reflecting the difficulties in treatment of progressive native coronary artery atherosclerosis. Our study demonstrated that the proportion of PCIs performed on bypass grafts relative to native vessels decreased over time despite the likelihood of greater anatomical complexity. This may reflect the advancing techniques in the treatment of native‐vessel chronic total occlusions with higher rates seen in this cohort than other published series.

Consistent with previous studies, we have shown that in‐hospital MACE rates and all‐cause mortality were higher in patients with previous CABG undergoing PCI to a bypass graft. Brilakis et al8 reported a higher in‐hospital mortality after bypass‐graft intervention when compared with native coronary intervention. In 2010, the APEX‐AMI (Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial looked at 5745 patients presenting with STEMI, including 128 patients with prior CABG. They reported that TIMI III flow was achieved less often on treatment of a bypass‐graft culprit lesion, and they found that the 90‐day mortality in these patients was higher compared with patients with prior CABG treated for a native culprit lesion (19% versus 5.7%).16 Further supportive data are provided by a small observational study by Mavroudis et al17 that looked at graft versus native‐vessel PCI and found that VG PCI had worse outcomes compared with native coronary PCI, with high rates of mortality, restenosis, and occlusion. They found that graft‐vessel PCI had 5 times higher rates of target‐vessel revascularization compared with those undergoing native‐vessel treatment, supporting the data provided our larger data set, although greater anatomical information and outcomes such as target vessel revascularisation were available.

To date there are limited data supporting native versus graft intervention in this patient cohort with no randomized trial data performed. In 2000, Mathew et al18 published data on patients with and without previous CABG undergoing PCI for unstable angina showing that although treatment of a native coronary lesion compared with a bypass graft reduced the likelihood of death, MI, and/or repeat revascularization, previous CABG was still associated with a higher risk when compared with non‐CABG patients undergoing PCI. Other studies such as that from the Mayo clinic, of 1072 patients undergoing primary PCI of which 128 had a history of prior CABG, showed that during 1 year of follow‐up, previous CABG was associated with adverse cardiac events, but not after adjustment for baseline characteristics, where only vein‐graft treatment was independently associated with adverse cardiac events, whereas previous CABG was not.19 The APEX‐AMI trial further added to this evidence by finding no difference in outcome between patients with prior CABG treated for a native culprit vessel compared with patients without a history of bypass. Our study has gone on to confirm these data in a large population of patients treated both electively and acutely with the longest follow‐up reported to date. This provides a strong rationale to support further randomized study in this increasingly seen patient cohort specifically the ongoing PROCTOR (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Native Coronary Artery Versus Venous Bypass Graft in Patients With Prior CABG) trial (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03805048), which is investigating this exact question.

The Pan‐London BCIS data set includes the complete collection of all PCI procedures performed in London, United Kingdom, representing unselected real‐world experience, including high‐risk patients often excluded from randomized controlled trials. We recognize that this study has several potential limitations. First, this was an observational study associated with the inherent biases of the study design; however, differences in baseline and clinical characteristics were adjusted in a multivariate analysis, and a propensity analysis was performed to further account for confounding. We report all‐cause mortality and although mortality tracking within the United Kingdom is robust, all other outcomes and complications are self‐reported without formal adjudication. Therefore, the analysis is potentially vulnerable to reporting biases, and complications may be underreported. In addition, we did not provide information about target lesion–related end points (ie, target‐vessel MI or revascularization) that would enable us to accurately assess the prognostic implication of native‐vessel versus vein‐graft intervention. Hence, we cannot differentiate whether the outcomes were mediated by differences in MI or requirements for repeat revascularization, and we also unfortunately can only report all‐cause and not cardiac‐specific mortality. Finally, our analyses report outcomes derived from grafts because the BCIS data set does not differentiate between venous and arterial grafts. Previous data derived from the NCDR CathPCI registry suggest that arterial grafts represented 2.5% of all PCI procedures undertaken to bypass grafts in the United States, although this did not report practice or outcomes in a primary PCI cohort specifically.8

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with prior CABG treated with PCI had greater comorbidities, but once these differences were adjusted for, prior CABG was not associated with mortality. Native‐vessel PCI was associated with improved outcomes compared with the treatment of vein grafts and prior to further study, native coronary arteries should be considered if amenable to PCI, as the target vessel of choice, over PCI to bypass grafts.”

Sources of Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute of Health Research via the RrFB scheme.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014409 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014409.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Chen L, Theroux P, Lesperance J, Shabani F, Thibault B, De Guise P. Angiographic features of vein grafts versus ungrafted coronary arteries in patients with unstable angina and previous bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1493–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fitzgibbon GM, Kafka HP, Leach AJ, Keon WJ, Hooper GD, Burton JR. Coronary bypass graft fate and patient outcome: angiographic follow‐up of 5,065 grafts related to survival and reoperation in 1,388 patients during 25 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, Thottapurathu L, Krasnicka B, Ellis N, Anderson RJ, Henderson W. Long‐term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: results from a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2149–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdel‐Karim AR, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Percutaneous intervention of acutely occluded saphenous vein grafts: contemporary techniques and outcomes. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22:253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen TT, O'Neill WW, Grines CL, Stone GW, Brodie BR, Cox DA, Grines LL, Boura JA, Dixon SR. One‐year survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction and a saphenous vein graft culprit treated with primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1250–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keeley EC, Velez CA, O'Neill WW, Safian RD. Long‐term clinical outcome and predictors of major adverse cardiac events after percutaneous interventions on saphenous vein grafts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brilakis ES, O'Donnell CI, Penny W, Armstrong EJ, Tsai T, Maddox TM, Plomondon ME, Banerjee S, Rao SV, Garcia S, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in native coronary arteries versus bypass grafts in patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery: insights from the veterans affairs clinical assessment, reporting, and tracking program. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:884–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brilakis ES, Rao SV, Banerjee S, Goldman S, Shunk KA, Holmes DR Jr, Honeycutt E, Roe MT. Percutaneous coronary intervention in native arteries versus bypass grafts in prior coronary artery bypass grafting patients: a report from the national cardiovascular data registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Windecker S, Neumann FJ, Juni P, Sousa‐Uva M, Falk V. Considerations for the choice between coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous coronary intervention as revascularization strategies in major categories of patients with stable multivessel coronary artery disease: an accompanying article of the task force of the 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iqbal J, Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, de Belder MA, Ludman PF, Giannoudi M, Gunning M, Zaman A, Mamas MA. Outcomes following primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with previous coronary artery bypass surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ludman PF. British cardiovascular intervention society registry for audit and quality assessment of percutaneous coronary interventions in the United Kingdom. Heart. 2011;97:1293–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huber MS, Mooney JF, Madison J, Mooney MR. Use of a morphologic classification to predict clinical outcome after dissection from coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the european society of cardiology (ESC) and the european association for cardio‐thoracic surgery (EACTS) developed with the special contribution of the european association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cole JH, Jones EL, Craver JM, Guyton RA, Morris DC, Douglas JS, Ghazzal Z, Weintraub WS. Outcomes of repeat revascularization in diabetic patients with prior coronary surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1968–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Varghese I, Samuel J, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention in native coronary arteries vs. Bypass grafts in patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2009;10:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welsh RC, Granger CB, Westerhout CM, Blankenship JC, Holmes DR Jr, O'Neill WW, Hamm CW, Van de Werf F, Armstrong PW. Prior coronary artery bypass graft patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mavroudis CA, Kotecha T, Chehab O, Hudson J, Rakhit RD. Superior long term outcome associated with native vessel versus graft vessel PCI following secondary PCI in patients with prior cabg. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mathew V, Berger PB, Lennon RJ, Gersh BJ, Holmes DR Jr. Comparison of percutaneous interventions for unstable angina pectoris in patients with and without previous coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Al Suwaidi J, Velianou JL, Berger PB, Mathew V, Garratt KN, Reeder GS, Grill DE, Holmes DR Jr. Primary percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction and prior coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J. 2001;142:452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]