Abstract

Background

Mindfulness-based programs have shown a promising effect on several health factors associated with increased risk of dementia and the conversion from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia such as depression, stress, cognitive decline, immune system and brain structural and functional changes. Studies on mindfulness in MCI subjects are sparse and frequently lack control intervention groups.

Objective

To determine the feasibility and the effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) practice on depression, cognition and immunity in MCI compared to cognitive training.

Methods

Twenty-eight MCI subjects were randomly assigned to two groups. MBSR group underwent 8-week MBSR program. Control group underwent 8-week cognitive training. Their cognitive and immunological profiles and level of depressive symptoms were examined at baseline, after each 8-week intervention (visit 2, V2) and six months after each intervention (visit 3, V3). MBSR participants completed feasibility questionnaire at V2.

Results

Twenty MCI patients completed the study (MBSR group n=12, control group n=8). MBSR group showed significant reduction in depressive symptoms at both V2 (p=0.03) and V3 (p=0.0461) compared to the baseline. There was a minimal effect on cognition – a group comparison analysis showed better psychomotor speed in the MBSR group compared to the control group at V2 (p=0.0493) but not at V3. There was a detectable change in immunological profiles in both groups, more pronounced in the MBSR group. Participants checked only positive/neutral answers concerning the attractivity/length of MBSR intervention. More severe cognitive decline (PVLT≤36) was associated with the lower adherence to home practice.

Conclusion

MBSR is well-accepted potentially promising intervention with positive effect on cognition, depressive symptoms and immunological profile.

Keywords: cognition, depression, anxiety, MCI, neurodegeneration, monocyte activation

Introduction

The number of people suffering from dementia is growing every year due to the increasing age of the world’s population. The number of patients with dementia is expected to double every 20 years.1 The dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is preceded by a prodromal stage referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI),2 which is characterized by a measurable decline of cognition, but preserved activities of daily living. Besides the cognitive symptoms, MCI patients often manifest neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) such as depression and anxiety or apathy and irritability.3,4 The presence of NPS increases the probability of converting to AD dementia.5 Advanced age is commonly accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation, which is also present in the central nervous system6,7 and which contributes to many age-related disorders, including cognitive dysfunctions and AD.8–10 Neurodegenerative disorders are associated with the early onset of immunosenescence,8,11 manifesting via increased numbers of senescent T cells, increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, mainly CRP, IL-6 and TNF, and also via changes in myeloid cells, which has been reported in MCI,12,13 as well as in AD dementia.14,15

Despite the fact that a lot of research has been focused on treatment strategies and many clinical trials with disease-modifying drugs are currently under way, there is no known effective treatment option that can stop or even slow down the progression of the disease.16,17 Therefore, non-pharmacological strategies influencing the risk/preventive factors of AD have been receiving a great amount of attention. Within this context, those methods based on different meditation practices are often studied with respect to cognitive benefit or preventive potential in the development of neurodegenerative diseases.18,19 Several studies have suggested that the practice of meditation might have a positive effect on regional atrophy rates20 as well as on multiple cognitive functions related to age-related cognitive decline or to neurodegeneration.21 In MCI subjects, mindfulness meditation has positively influenced emotional regulation22 as well as general mental health and well-being.23 Specifically, it may improve anxiety and depression.24 Different meditation techniques have also been studied in patients with AD dementia, identifying significant effects or trends in many areas, including decreased cognitive decline, a reduction in perceived stress, improvement of the quality of life, as well as increased functional connectivity, cerebral blood flow and brain volume changes in specific cortical areas.25–32

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) developed at the University of Massachusetts33 is an 8-week program originally inspired by Buddhist teachings with the use of mindfulness meditation, body awareness and yoga. Mindfulness is defined as awareness developed through one’s intentionally focused non-judgmental attention on the present moment, which can be achieved through a variety of meditative practices.33,34 Over the years, many other Mindfulness-Based Programs (MBPs) have been developed.35

MBSR studies with healthy elderly have shown a significant increase in physical health perception and decreased depressive symptoms.36–39 Others have shown improvement in long-term memory and in attention and working memory,40 as well as in cognitive functions generally.41 The long-term effect of MBSR might depend on the levels of continued meditation practice.42

MBPs may reduce chronic inflammation43 via changes of inflammatory genes’ expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and via reduction of pro-inflammatory markers and an increase of cell-mediated immune and anti-aging response.44 The ability of MBSR to change the levels of inflammatory cytokines has been also reported.37 Monocytes are perceived as the central sensors and regulators of inflammation. The dysregulation of their phenotype and function has already been linked with aging.45,46 Among three monocyte subsets, defined by surface markers as classical (CD14++CD16−), non-classical (CD14dimCD16++), and intermediate (CD14++CD16+), the non-classical and intermediate monocyte proportions increase in various chronic inflammatory disorders,46,47 whereas some activities such as physical exercise may decrease their numbers.48

Recent pilot data with MCI participants (n = 14) showed a trend towards improved cognition (ADAS-Cog, TMT A and B, RAVLT, Cowat, Animal naming, BNT) and less bilateral hippocampal volume atrophy in the MBSR group compared to the control subjects.49 A longitudinal mixed-methods observational study with a one-year follow-up period (n = 14) showed significant improvement in cognitive function (MOcA) and everyday activities functioning.41 However, there is not enough data on the feasibility of MBPs with MCI subjects. In a pilot trial with 9 MCI patients, MBSR was found to be safe and feasible, however, the authors recommend that studies with larger samples be conducted.49 Considering that patients with MCI have specific characteristics and needs in comparison to the healthy population (such as problems with cognition and mood disturbances), a discussion on how to deliver MBPs treatment in a feasible way might be necessary.

Different meditation practices are associated with spirituality since it is a part of many religions. Although MBSR is a secular behavioral medical program, many participants have reported that the course deepened their sense of spirituality.50–52 Studies have shown that cultivating both spirituality and mindfulness leads to MBPs having a positive effect on physical and mental health.53–55 One study examining the effect of Kirtan Kriya meditation suggests only a marginal role being played by spiritual level in influencing cognition.56 Nevertheless, higher levels of spirituality have been associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline in patients with AD57 and in the healthy elderly.58,59 Therefore, spiritual well-being could potentially work as a mediator of the MBSR effect, especially on depressive symptoms and anxiety.

The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility and effect of MBSR compared to standard cognitive training: (1) on cognitive functions (2) on depressive symptoms and anxiety and (3) on the immunophenotype of peripheral blood monocyte subsets, the plasma level of inflammatory mediators and phagocytic activity and compare it with the effects of cognitive training as an active control. Thus, the effect of MBSR on cognition, depressive/anxiety symptoms and immunological profile represent primary outcome variables. Moreover, we analyzed feasibility for this intervention group and explored whether the number of post-intervention practice days or level of spiritual well-being affects the effect of MBSR – these were secondary outcome variables. We also tried to prevent the limitations of previous studies such as a missing control intervention group and in order to diminish the learning effect, we used cognitive tests suitable for the MCI population like Cogstate test battery.60

Based on our previous knowledge and theoretical models, we hypothesized that although MBSR contrary to cognitive training is not a primary cognitive intervention, it will influence slow cognitive decline comparably to standard cognitive training and through its brain maintenance mechanism, also influence NPS and favorably change immunological profile resulting in a reduction of systemic inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

This interventional case-control study was conducted at St. Anne’s University Hospital in Brno, Czech Republic. Participants were selected from the Czech Brain Aging Study, which is a longitudinal study on aging with biomarkers of AD.61 The inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of MCI, based on Petersen16 criteria assessed by a consensual MRI evaluation of the brain, a neurological and a neuropsychological examination, (2) age 55+ years. Exclusion criteria: high levels of depressive symptoms as assessed by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) with a score above 10 points or a presence of psychiatric disorders that may affect cognitive functions.

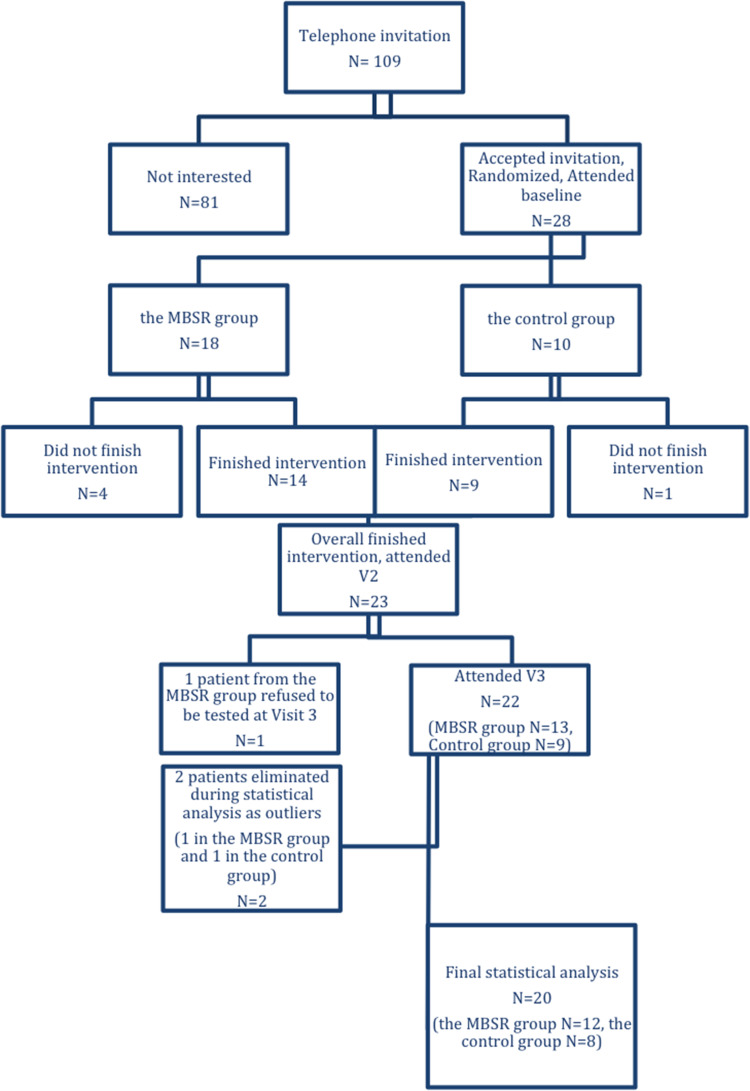

One hundred and nine subjects with MCI from the Czech Brain Aging study were invited randomly over the phone to participate in this study, 28 participants accepted the invitation and entered the study (Figure 1). The participants were assigned to one of the two groups according to the sequence of entering the study in a ratio 2:1 (MBSR group:Control group). The MBSR group (n=18) underwent an 8-week MBSR course, while the control group (n=10) underwent cognitive training. The distribution was based on the order of entry into the study – after assigning two patients to the MBSR group, one was assigned to the control group and so on. The order of contacting the potential participants was random. Based on our knowledge on good adherence in cognitive training interventions62–64 and a higher probability of drop out from the more challenging MBSR intervention49 we decided to create a larger MBSR group.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the trial.

Assessment

The local St. Anne’s University Hospital Institutional Review Board reviewed the entire protocol and agreed that all procedures were done in accordance with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation of this institution and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained at the beginning. The scientific board of The Alzheimer Foundation in the Czech Republic approved the study’s description with outcome variables and the entire protocol specification. Participants’ cognitive functions, depressive symptoms and anxiety were measured at baseline, at visit 2 (V2) – immediately after the 8-week intervention and at visit 3 (V3) – 6 months after the intervention. Immunological parameters were measured at baseline and at V2.

Interventions

MBSR Intervention

Participants in the MBSR group completed an 8-week-long MBSR intervention based on the authorized curriculum Guide.65 MBSR was administered by trained and certified instructor. The intervention began first with the “introduction to mindfulness” session, followed by 8 weekly sessions (2.5 hours long) and 1 “retreat in silence” day (6 hours long). Each week, participants were given materials for home practice. Mindfulness was cultivated through both formal (body scan, sitting meditation, mindful movement, working with difficulties, meditation with imagination, etc.) and informal practices (bringing mindfulness to routine activities, including short breathing meditation, an analysis of pleasant and unpleasant events and stressful communication, etc.). Home practice (30–50 minutes daily) was practised by guided audio recordings. The mindful movement sequence was adapted to the patients’ physical limitations – specific recordings guiding participants through more gentle movements were prepared. Besides, the length of formal practices such as sitting meditation, mindful movement and body scan were shortened from 45 to 30 minutes, in agreement with the previous study.49

Cognitive Training

Participants in the control group underwent cognitive training – an active intervention that has been reported to produce moderate-to-large beneficial effects on memory and executive functions.66,67 While cognitive training is a method that tries to compensate for the loss of cognitive functions without influencing the AD pathophysiological mechanism, MBSR might affect brain maintenance. During their 8-week period, they met once a week for 2.5 hours to practice in group cognitive tasks focused on specific cognitive domains. The set consisted of tasks aiming at improving memory, attention, and logical thinking. All tasks were given in an entertaining way with an emphasis on group cohesion without any pressure on rivalry or excessive performance. All meetings were introduced by a short lecture about some cognitive domain. Participants were given home practice materials once a week, which included exercises for individual cognitive training. All exercises were taken from popular literature on cognitive exercises to the elderly.68–70 It contained exercises such as recognition of well-known melodies, line-ups of movie couples, recognizing minor changes in the room, the Match Match card game, collectively creating a story, Word Chain, etc. The time range of cognitive training (group and home practicing) corresponded to the MBSR time range and the control group members received as much support and attention as members of the MBSR group. After finishing their 8-week training, participants were instructed to continue in their cognitive tasks and they continued to obtain additional cognitive training materials for the next 6 months.

Primary Outcomes

Cognitive Assessment

To measure cognitive performance, 3 paper-and-pen tests – the Stroop test,71 the Philadelphia Verbal Learning Test (PVLT),72 and the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT-FAS)73 and 4 computer Cogstate tests60 were administered. The tests captured performance in different cognitive domains: attention (the Cogstate Identification Test), psychomotor speed (the Cogstate Detection Test), visual learning (the Cogstate One Card Learning Test) and working memory (the Cogstate One Back Test), memory (PVLT), and executive functions (the Stroop test and COWAT – FAS). The sum of recalled words over 5 learning trials and the number of words recalled after a 20-minute delay in PVLT were combined into a “Memory score” domain through converting the values to z-scores and then averaging the tests. The same procedure with the Stroop test and COWAT–FAS was chosen to create an “Executive function” domain. All tests were designed for repeated administration with minimal practice or learning effects, so we could use them repeatedly throughout the study. The psycho-cognitive scales were administered by two blinded raters.

Depression, Anxiety

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)74 was used to assess the level of depressive symptoms. GDS is self-report measure; subjects respond 15 items in “Yes/No” format. Scores with a range between 0–4 are considered normal, 5–8 indicate mild depression; 9–11 indicate moderate depression; and 12–15 indicate severe depression. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)75 was used to assess anxiety level. BAI is self-report measure; 30 questions explore common symptoms of anxiety which have been perceived by the participant in the past month. Scores of 0–21 indicate low anxiety, 22–35 indicate moderate anxiety, scores of 36 and above indicate potentially concerning levels of anxiety. Both questionnaires were validated with good psychometric properties.71,72

Immunophenotyping

Peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) from baseline and V2 were isolated from 10 mL of non-coagulated blood by gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (density 1.077 g/mL; STEMCELL technologies) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. All blood samples were drawn before administration of psycho-cognitive scales between 7–10 AM. Isolated PBMCs were cryopreserved using 10% fetal bovine serum in DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen for further batch FACS analysis. The thawed cells were stained using lineage antibodies (anti-CD3-biotin, anti-CD19-biotin, CD20-biotin, CD56-biotin, CD66b-biotin, CD235α-biotin followed by streptavidin eFluor405 staining), anti-CD45-PerCPeFluor710, anti-CD14-eFluor506, anti-CD16-APC, anti-CD86-PE anti-HLA-DR-FITC (all eBiosciences). A LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to exclude dead cells from the analysis. Lin− CD45+ leucocytes were classified into three monocyte subsets based on the expression of CD14 and CD16 – classical (CD14++CD16−), intermediate (CD14++CD16+) and non-classical (CD14dimCD16++).76 Sample acquisition was performed using FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo v.10 (Tree Star).

Phagocytosis Assay

The pHrodo Green S. aureus BioParticles Phagocytosis Kit for Flow Cytometry (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations for detecting phagocytic activity in fresh whole blood samples. Sample acquisition was performed via FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo v.10 (Tree Star).

Plasma Analysis – Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The plasma levels of CRP were detected in diluted plasma samples (1:7000) using a DuoSet ELISA kit, while Quantikine HS ELISA Human TNFα Immunoassay and Human IL-6 Immunoassay were used to measure TNFα and IL-6 in undiluted plasma samples. The ELISA assays were used as recommended by the manufacturer (R&D Systems). Data acquisition was performed using a Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Secondary Outcomes

Spiritual Well-Being Assessment

Participants filled in the SHALOM Questionnaire (Spiritual Health and Life-Orientation Measure) designed to measure their spiritual well-being.77 Fisher’s concept assumes that the development of spirituality leads to certain clearly defined values and attitudes that are mirrored in 4 domains of spiritual health and manifests one´s relationship to itself (Personal domain), to others (Communal domain), to the environment (Environmental domain), and to God or any other transcendental characteristic (Transcendental domain). An abbreviated 11-item Czech version was used for making the analysis.78

Feasibility Questionnaire

To assess the acceptability and feasibility of MBSR, all MBSR participants completed a feasibility questionnaire at V2 designed specifically for this study. The questionnaire inquired about the attractiveness of the course, the acceptability of session length and home practices, the management of the home practice, the reasons for skipping home practice, the most and least favorite practices, the most appealing aspects of the course and the suggested length of sessions and home practices for future participants with MCI. Multiple choice answers were allowed.

Post-Intervention Practice

After finishing the 8-week training, participants were instructed to continue in the acquired mindful practices daily (mindful eating, body scan, etc.). They were distributed a simple diary with all the options of mindful practices and they were asked to tick the practice they performed each day. The diary was later analyzed and used as an intervening variable for making the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the values at all three time points within each group, the Wilcoxon test with the Hochberg correction for multiple testing was used.79 The Mann–Whitney test with the Hochberg correction for multiple testing was used to compare the effects of the two treatments – the MBSR course and cognitive training. Statistical analysis was performed using R and RStudio and the chosen significance level was α = 0.05. For each test, the effect size was calculated as the difference between two medians divided by a pooled standard deviation of the data.

In the V3 analysis of the MBSR group, we also examined a possible intervening variable, which could be the number of post-intervention meditation days. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated for the number of meditation days and the difference between the baseline and V3 scores for each test and the significance of the coefficient was tested. Another objective was to examine the relationship between SHALOM and the effect of the intervention. For this purpose, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used.

The participants’ feasibility questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics because of the small sample size of the participants. All analyses were blinded.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the initial 28 participants, 5 patients did not finish the 8-week intervention, 4 in the MBSR group (due to a loss of motivation (n=1) and physical difficulties such as surgery, pain, worsening of the condition of a close person (n=3)) and 1 in the control group (a loss of motivation) and they stopped attending regular meetings. Therefore, post-intervention values are available for 23 patients; however, 2 more patients were eliminated during the statistical analysis as outliers (they converted from MCI to dementia, 1 in the MBSR group to AD dementia and 1 in the control group to Frontotemporal dementia), while 1 patient refused to be tested at V3. Therefore, the statistical analysis was carried out on 20 patients, 12 patients in the MBSR group and 8 patients in the control group (Figure 1). Participant baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The between-group differences were not significant on the level of significance α = 0.05.

Table 1.

Demographics and Test Performance at Baseline (Mean, SD) for MSBR (n=12) and Control (n=8) Group

| Overall (n=20) | MBSR (n=12) | Control (n=8) | Group Effect (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range 57–91 y) Mean ± SD | 74 ± 6.9 | 73.83 ± 7.04 | 74.25 ± 7.25 | 0.374 |

| Gender (Female/Male) | 13/7 | 6/6 | 7/1 | 0.213 |

| Education years | 14.3 ± 2.79 | 14.08 ± 3.08 | 14.63 ± 2.45 | 0.611 |

| MMSE Mean ± SD | 27.26 ± 1.63 | 26.82 ± 1.72 | 27.875 ± 1.36 | 0.302 |

| GDS score Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 3.39 | 6 ± 3.19 | 3.25 ± 3.15 | 0.075 |

| BAI score Mean ± SD | 11.45 ± 11.22 | 14.92 ± 12.42 | 6.25 ± 6.92 | 0.053 |

| Shalom Mean ± SD | 36.7 ± 11.73 | 39.5 ± 10.03 | 32.5 ± 13.47 | 0.231 |

Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety and Cognition

The MSBR group showed a significant decrease in GDS score between baseline and V2 (p=0.03) and baseline and V3 (p=0.0461). No significant differences were observed in cognitive tests or BAI scores between baseline and V2 or V3. In the control group, no significant differences between baseline and V2 or V3 were present in any test at a level of significance α = 0.05 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Test Performance (Median, Interquartile Range) and Results for MBSR (n=12) and Control (n=8) Group, Obtained by One-Sample Wilcoxon Test

| Baseline | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 2 vs Baseline | Visit 3 vs Baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | p | d | Median (IQR) | p | d | |

| MSBR group, n=12 | |||||||||

| Memory score | 0.01 (−0.89–0.32) | 0.07 (−0.64–0.32) | 0.05 (−0.65–0.32) | −0.06 (−0.35–0.3) | 1 | −0.103 | −0.21 (−0.33–0.22) | 1 | −0.521 |

| Executive functions | −0.05 (−0.3–0.38) | 0.11 (−0.51–0.38) | 0.01 (−0.4–0.38) | −0.08 (−0.44–0.15) | 1 | −0.182 | −0.11 (−0.26–0.42) | 1 | −0.191 |

| Cogstate DET | 2.56 (2.52–2.68) | 2.53 (2.48–2.68) | 2.54 (2.48–2.68) | −0.04 (−0.07 – −0.02) | 0.178 | −0.685 | −0.03 (−0.08–0.02) | 0.883 | −0.306 |

| Cogstate IDN | 2.76 (2.71–2.81) | 2.72 (2.71–2.81) | 2.75 (2.73–2.81) | −0.02 (−0.04–0.01) | 0.647 | −0.53 | −0.02 (−0.05–0.01) | 1 | −0.312 |

| Cogstate OCL | 0.93 (0.86–1.04) | 0.93 (0.86–1.04) | 0.91 (0.82–1.04) | −0.01 (−0.04–0.07) | 1 | −0.114 | −0.04 (−0.11–0.02) | 1 | −0.38 |

| Cogstate ONB | 1.27 (1.15–1.39) | 1.23 (1.07–1.39) | 1.26 (1.11–1.39) | 0 (−0.09–0.11) | 1 | 0 | 0 (−0.08–0.05) | 1 | 0 |

| GDS | 5.5 (4.5–8.25) | 3 (1–8.25) | 2.5 (1–8.25) | −3.5 (−4.25 – −1.75) | 0.03 | −1.398 | −2 (−5.25 – −1) | 0.046 | −0.559 |

| BAI | 11 (8.25–17.5) | 10.5 (4–17.5) | 11 (7.25–17.5) | −1.5 (−10 – 4.25) | 1 | −0.147 | −1.5 (−5 – 2.75) | 1 | −0.141 |

| Control group, n=8 | |||||||||

| Memory score | 0.24 (−0.74–0.82) | 0.25 (−0.32–1.29) | 0.45 (−0.57–0.97) | 0.03 (−0.65–0.74) | 1 | 0.034 | 0.1 (−0.08–0.5) | 0.834 | 0.156 |

| Executive functions | −0.32 (−0.4–0.08) | 0 (−0.22–0.19) | −0.28 (−0.35 – −0.09) | 0.18 (−0.23–0.66) | 1 | 0.286 | −0.02 (−0.28–0.05) | 0.834 | −0.061 |

| Cogstate DET | 2.52 (2.46–2.58) | 2.53 (2.52–2.64) | 2.52 (2.47–2.6) | 0.04 (0–0.08) | 0.560 | 0.72 | −0.01 (−0.04–0.07) | 0.834 | −0.200 |

| Cogstate IDN | 2.74 (2.69–2.75) | 2.71 (2.7–2.75) | 2.73 (2.71–2.75) | 0.01 (−0.04–0.02) | 1 | 0.112 | −0.01 (−0.02–0.01) | 0.834 | −0.203 |

| Cogstate OCL | 1 (0.98–1.02) | 0.95 (0.9–0.97) | 0.85 (0.82–0.93) | −0.07 (−0.08 – −0.03) | 0.114 | −1.767 | −0.15 (−0.17 – −0.08) | 0.114 | −1.751 |

| Cogstate ONB | 1.21 (1.1–1.34) | 1.32 (1.22–1.34) | 1.16 (0.97–1.23) | −0.04 (−0.12–0.1) | 1 | −0.167 | −0.14 (−0.2 – −0.08) | 0.296 | −0.841 |

| GDS | 3 (0.75–4.5) | 2 (1.75–2.25) | 4 (1.75–5.75) | 0 (−1.25–1) | 1 | 0 | 0 (−0.25–2.5) | 0.834 | 0 |

| BAI | 5.5 (1.75–7) | 2.5 (1–9.5) | 7.5 (3.5–9.25) | −0.5 (−4 – 1.5) | 1 | −0.085 | 2 (0–2.5) | 0.338 | 0.974 |

Note: Bold formatting indicates significant results.

Abbreviations: p, adjusted p-value (Hochberg correction for multiple testing), d, effect size.

The Mann–Whitney test with the Hochberg correction for multiple testing showed significant between-group differences in Cogstate DET (p=0.0493) between baseline and V2. Psychomotor speed improved in the MBSR group, while it worsened in the control group during this period. We also saw a significant difference in GDS values (p=0.0497) in the group comparison between baseline and V3; the values decreased in the MSBR group and did not change in the control group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results for MBSR (n=12) and Control (n=8) Between-Group Comparison, Obtained by Mann–Whitney Test

| MSBR vs Control Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 2 vs Baseline | Visit 3 vs Baseline | |||

| p | d | p | d | |

| Memory score | 0.938 | −0.124 | 0.847 | −0.616 |

| Executive functions | 0.885 | −0.494 | 0.847 | −0.195 |

| Cogstate DET | 0.049 | −1.429 | 0.847 | −0.187 |

| Cogstate IDN | 0.938 | −0.560 | 0.847 | −0.099 |

| Cogstate OCL | 0.352 | 0.739 | 0.195 | 1.267 |

| Cogstate ONB | 0.938 | 0.179 | 0.847 | 0.808 |

| GDS | 0.112 | −1.464 | 0.05 | −0.64 |

| BAI | 0.938 | −0.114 | 0.847 | −0.416 |

Note: Bold formatting indicates significant results.

Immunophenotyping

Here we analyzed the relative percentage of monocytes – classical (CD14++CD16−), non-classical (CD14dimCD16++), and intermediate (CD14++CD16+) subsets and also activation status through the surface expression of HLA-DR and CD86.

We did not find any significant changes in the proportion of monocyte subsets either within the time points or in the MSBR versus the control groups (Table 4). Interestingly, an analysis of the steady-state activation of monocytes showed a decreased expression of CD86 within the groups. Specifically, in CD14+ and CD14+CD16+ monocytes of the MBSR group and CD14+ monocytes in the control group (Table 4). An analysis of the phagocytic activity of the PBMCs did not show any significant differences (Table 4). Furthermore, we evaluated the effect of MBSR on plasma level of TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP. We did not observe any significant differences between the subjects either before or after MBSR intervention (data not shown).

Table 4.

Changes in Imunophenotype (Mean, SD) for MSBR (n=12) and Control (n=8) Group, Obtained by One-Sample Wilcoxon Test

| Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Visit 2 (Mean ± SD) | Wilcoxon Test Value | p-value | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Visit 2 (Mean ± SD) | Wilcoxon Test Value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % phagocyting cells | 15.10 ± 6.82 | 14.58 ± 9.52 | 31.00 | 0.57 | 19.61 ± 7.13 | 16.51 ± 9.60 | 4.00 | 0.22 |

| Monocyte subsets | ||||||||

| Classical (%) | 84.58 ± 4.33 | 80.14 ±5.72 | 8.00 | 0.05 | 82.21 ± 6.39 | 81.90 ± 6.49 | 7.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate (%) | 4.29 ± 2.05 | 5.43 ± 2.41 | 57.00 | 0.53 | 4.92 ± 2.50 | 4.45 ± 1.90 | 10.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-classical (%) | 5.05 ± 2.78 | 7.06 ± 3.74 | 67.50 | 0.08 | 6.50 ± 3.50 | 6.60 ± 2.37 | 13.00 | 1.00 |

| Changes in activation of monocyte subsets | ||||||||

| MHC-II on classical (GMF) | 442.00 ± 94.58 | 465.33 ± 90.98 | 50.50 | 0.39 | 466.83 ± 122.54 | 413.33 ± 99.63 | 4.00 | 0.22 |

| MHC-II on intermediate (GMF) | 1203.67 ± 298.74 | 1262.08 ± 306.91 | 43.00 | 0.79 | 1349.0 ± 368.96 | 1363.83 ± 318.88 | 12.00 | 0.84 |

| MHC-II on non-classical (GMF) | 608.33 ± 202.94 | 580.25 ± 168.65 | 27.00 | 0.38 | 692.33 ± 236.97 | 629.67 ± 190.19 | 5.00 | 0.31 |

| CD86 on classical (GMF) | 363.17 ± 39.15 | 290.83 ± 68.84 | 5.00 | 0.01 | 359.50 ± 51.27 | 318.33 ± 41.83 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| CD86 on intermediate (GMF) | 562.08 ± 118.49 | 507.75 ± 124.79 | 12.00 | 0.03 | 535.50 ± 81.35 | 494.50 ± 79.41 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| CD86 on non-classical (GMF) | 393.50 ± 117.62 | 357.17 ± 84.07 | 23.50 | 0.24 | 384.0 ± 100.02 | 371.17 ± 48.76 | 6.00 | 0.40 |

| Plasma analysis | ||||||||

| hsCRP (mg/l) | 1.57 ± 1.65 | 1.49 ± 1.55 | −11.00 | 0.63 | 1.72 ± 1.66 | 1.15 ± 1.62 | −7.00 | 0.56 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 1.57 ± 0.65 | 2.00 ± 1.31 | 24.00 | 0.32 | 2.40 ± 1.82 | 2.48 ± 2.86 | 2.00 | 0.95 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 1.12 ± 0.32 | 1.29 ± 0.44 | 38.00 | 0.10 | 1.07 ± 0.38 | 1.02 ± 0.37 | −20.00 | 0.20 |

Note: Bold formatting indicates significant results.

Post-Intervention Practice and Spiritual Well-Being

In the MBSR group, we examined the relationship between the effect of mindfulness intervention and the number of post-intervention practice days. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated between the number of practice days and the differences in the baseline and V3 cognitive, GDS and BAI scores. No significant correlation between the test results and the number of practice days was found. The average number of post-intervention practice days was M = 111.42; SD = 67.89 (0 to 180 days), while there was a considerable divergence; 3 participants practiced only from 0 to 16 days, while 9 participants practiced more than 100 days.

Another objective was to examine if the level of spiritual well-being (SHALOM score) affected the effect of MBSR intervention. The change of cognitive, GDS and BAI scores between baseline and V3 did not correlate with the baseline SHALOM score.

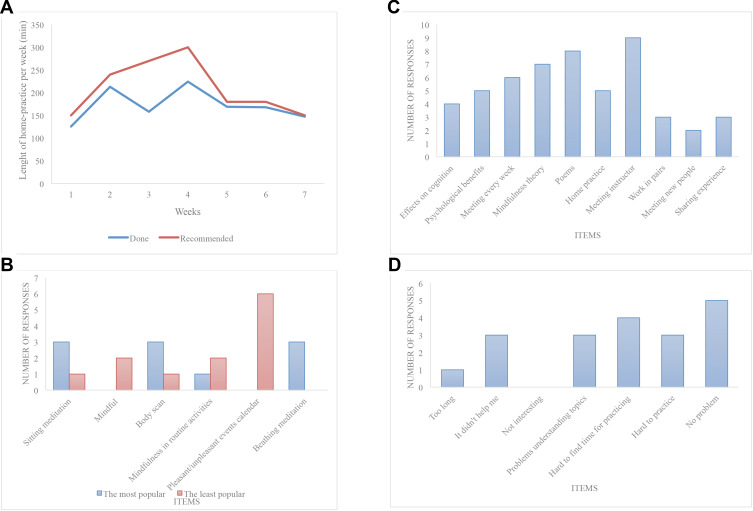

MBSR Feasibility

Fourteen subjects completed the intervention and feasibility questionnaires. Participants generally enjoyed the MBSR intervention (there were only positive or neutral responses and no negative responses checked in the questionnaire concerning the attractiveness of the intervention and the length of both sessions and home practices). In the recommendation part of the questionnaire concerning ideal frequency, and the length of sessions and home practice for future participants with cognitive impairment, the participants suggested the following: having sessions once a week (SD 0.3 week) for 1.9 hours (SD 0.4 of an hour) with a home practice of 25 minutes (SD 9.2 minutes) a day. Participants reported meditating on average 5.1 days a week (SD 1.4). The most frequent reasons for not practicing at home were not enough time, forgetting to do the practice, the inability to concentrate or not believing it to be helpful. Six subjects checked “unspecified” as one of their reasons for not practicing at home.

In Figure 2, we present the adherence to home practice 2a, the most and the least popular practices 2b, the most appreciated aspects of MBSR 2c, and the challenging aspects of MBSR 2d.

Figure 2.

Adherence to home practice (A), the most and the least popular practices (B), the most appreciated aspects of MBSR (C) and the challenging aspects of MBSR (D).

We also explored the influence of baseline levels of cognitive decline, anxiety and depression on adherence to home practice. Participants with more severe cognitive decline (PVLT ≤ 36) tended to adhere to home practice less (mean 146 minutes/week) than those with milder cognitive decline (PVLT > 36) (mean 195 minutes/week). This difference was mostly present in the 4th week, when more severely cognitively affected participants meditated only 58% of the recommended time, whereas those with better cognitive skills were able to keep up with 89% of the recommended time.

There was no difference between subjects with low (BAI <10) and high (BAI ≥ 10) anxiety levels, nor between subjects with low (GDS <6) and higher (GDS ≥ 6) depression levels in their adherence to meditation home practice.

Discussion

We have shown that MBSR intervention significantly influenced the level of depressive symptoms both immediately and 6 months after the intervention in elderly subjects with MCI. While the majority of analyzed markers were unchanged, in a group comparison, the MBSR group was more effective in decreasing long-term depressive symptoms level than the control group. The MBSR intervention also showed a better effect on short-term psychomotor speed improvement than the control intervention. No effects or between-group differences on anxiety or other cognitive tests were observed. In this study, we did not observe any significant effect of MBSR intervention on the plasma level of inflammatory mediators (IL-6, TNF-α and CRP), on changes in monocyte subset distribution or on the activity of phagocytes. Nevertheless, the activation status (assessed through the expression of CD86) was decreased in classical monocytes in both groups, while in the MBSR group, this was also true in the intermediate monocyte subset. Numerous intervention strategies have been investigated in order to modulate or reverse the process of immunosenescence; among those, extended physical exercise80 and other psychosocial activities79,81 have been intensively studied. One limitation of this study is the length of intervention, as many reported positive effects were mostly achieved with prolonged interventions.

The positive effect of MBSR on depressive symptoms in our study is consistent with other studies showing a positive effect of MBSR on mental health,23 anxio-depressive symptoms and aging-related quality of life in the amnestic MCI population.39 Our findings confirm that the intervention is also effective in MCI patients and that the effect is persistent even 6 months after the end of the intervention. Depressive symptoms are the most common behavioral symptoms in MCI82,83 and they are connected with an increased risk of progression to dementia in MCI patients.84 The findings suggest that MBSR presents a promising method to reduce frequently occurring depressive symptoms in this population.3,4

It should be mentioned that the average mean level of depressive symptoms at the baseline was higher in the MBSR group than in the control group. However, the between-group differences were not significant at α = 0.05. Although the analysis did not focus directly on baseline, V2 or V3 scores, but was instead focused on their differences, this fact could have potentially highlighted the effect of MBSR on this variable. We can hypothetically consider that if the mean depressive symptom level in this group had been smaller, the effect of the intervention would also have been smaller.

Surprisingly, we did not observe any significant effect on anxiety level, although we could see a trend of decreased mean anxiety after MBSR intervention. This finding could be explained by the increased presence of physical difficulties in the elderly, which can be falsely interpreted as increased anxiety by the BAI questionnaire and therefore mantle the MBSR effect on pure anxiety symptoms.24

Based on previous studies, MBPs can have both a direct and indirect effect on cognitive performance. Indirectly, MBPs can influence factors that can augment the likelihood of hippocampal damage, such as stress, depression, and metabolic syndrome.85 There are a few possible ways of how MBPs can mediate reduced stress and depression. The studies support the role MBPs play in the diminution of steroid hormones,86–90 decreasing systemic inflammation through the regulation of cytokines91–94 and the restoration of systemic levels of serotonin after inflammation reduction.95,96 Research on the contribution of MBPs on metabolic syndrome control concerns their role in the reduction of inflammation,97 the restoration of normal oxidative status,98–104 the reduction of white matter hyperintensities (WMH)85 and the increase of insulin sensitivity,105 thus it focuses on how MBPs contribute to a brain maintenance. Directly, MBPs such as MBSR could enhance cognition through positive structural changes in brain structures relevant for memory,106,107 as well as building a cognitive reserve through the repeated activation of attentional functions.108,109

In our study, we observed significantly improved psychomotor speed performance in the MBSR group compared to the control group. These results are consistent with a similar study resulting with non-significant effect on cognition.39,49 However, the improvement in psychomotor speed shown in our study had not yet been reported, whereas other studies reported improvements in attention, working memory and long-term memory40 or in cognitive functions generally.41 Our results could be viewed with the fact that we used more sensitive tests suitable for the MCI population with a minimal learning effect (in contrast with global screening tests such as MoCA and MMSE used in other studies).41,49 Some studies suggest that patients with depression perform significantly slower than healthy controls,110,111 thus better psychomotor speed in our study could be hypothetically connected to the improvement of depressive symptoms in the MBSR group. It is possible that some of the effects of MBSR could be universally attributed to/mediated by the reduction of anxiety and depression.112

Our preliminary results suggest that MBSR is not a program that can improve cognitive functions more rapidly compared to standard cognitive training. However, the interpretation of these results does not necessarily indicate the ineffectiveness of MBSR in this area, as the results are compared to active intervention.67 In this context, the observed MBSR effect on psychomotor speed may be emphasized. Moreover, unlike cognitive training, MBSR represents a more complex intervention, with an effect on depressive symptoms and immunological variables. There is a presumption that MBSR, like other mindfulness programs, can affect the pathophysiological pathways associated with AN neurodegeneration. Thus, MBSR could potentially affect negative pathophysiological cascades and bring a longer-term effect with the same 8-week effort.113–115

Our results may be related to the findings of a systematic review that question the effect of MBSR on cognition.116 In this review, there was no evidence of improvement in attention and executive function, although there was preliminary evidence of improvement in working memory, autobiographical memory and global processes, such as cognitive flexibility and meta-awareness. The authors hypothesize that MBSR has more of a protective effect than an enhancing effect, and mindfulness seems to prevent further cognitive decline instead of improving cognitive functions in the ageing population. This hypothesis seems to be confirmed in the empirical field, where prolonged and adapted Mindfulness-Based Programs have successfully slowed down cognitive decline in comparison to control and muscle relaxation groups.117

The positive effect of MBSR on cognition reported in another study41 could draw attention to the need for MBSR to be adapted to the specific MCI population and the length of the intervention, as was done in the mentioned study.

Our data obtained from the feasibility questionnaires suggested that MCI participants generally enjoyed the MBSR intervention and were capable of keeping up with the rather intensive demands of home practice; this is also consistent with the previously reported data.49 We think that one of the possible reasons behind weaker adherence to the practice in the third and fourth weeks might be due to the increased amount of home practice in these weeks.

Our finding that participants with more severe cognitive decline tended to adhere less to the recommended amount of home practice might be either due to worsened memory, and therefore the inability to remember to practice regularly, or problems in organizing one’s daily routine due to worsened executive functions and cognitive disorganization. No notable changes in terms of adherence were found when comparing different levels of anxiety and depression, suggesting that these do not seem to play a dominant role in determining engagement with home practice in MCI patients. The participants’ responses also suggested that they tended to favor formal practice more than informal. We think that since informal practice does not have the framework of clearly defined formal practice, it might be too difficult to grasp at first and MCI patients might not be sure how to do it; therefore, carefully explaining the purpose of bringing mindfulness to life could be helpful when assigning home practice throughout the course.

The search for the relationship between MBPs and changes in the immune system parameters always provides very heterogenic data.44 Nevertheless, some of these findings are promising; this includes the reported decrease in plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines.37,118,119 Most of the reported cytokines strongly influence innate immunity, including monocytes. In our study, we did not observe any significant changes in the plasma levels of inflammatory mediators. This could partially be explained by the heterogenic experimental designs in literature since the effects of mindfulness meditation on immune system biomarkers are varied, the findings remain inconclusive and are also dependent on the intensity of the exercise as reported in some studies.44 Here, we focused on MBSR intervention-induced changes in immune phenotype, mainly the levels of inflammatory cytokines characterizing immunosenescence associated chronic low-grade inflammation and changes in monocyte subsets and their activation and phagocytosis in PBMCs. The higher numbers of senescent T cells have indeed also been reported in the context of accelerated senescence, but as T cells are long-lived and the pool of senescent T cells accumulates throughout life, it is unlikely that the proportion of senescent T cells can be changed by MBSR intervention within the 8 weeks of the study. We therefore focused on changes in inflammatory cytokines and monocytes from peripheral blood.

Here we report the change of activation status assessed through the expression of CD86 in both the MBSR and control groups at V2. These observations indeed need to be confirmed by an analysis of other inflammatory markers, the performance of functional tests in sorted monocyte subsets and including additional appropriate controls.

The relatively short 8-week interventions could hypothetically be too short to influence cognitive functions, which are less dynamic than mood disorders. Although, in our study, we did not find any correlation between the effect of MBSR and the number of post-intervention practice days. In contrast, the meta-analysis reports small but still significant association between MBSR home practice and intervention outcomes.120 It is possible that a longer intervention could have a positive effect on cognitive functions, as some studies on healthy elderly people121,122 as well as on patients with MCI41 and AD117 suggest. In our data, we see a considerable divergence in relation to post-intervention practice. In the next studies, it is therefore advisable to control and to motivate the participants, and to include follow-up sessions. The lack of correlation between the practice and cognition outcome scores in our findings potentially argues against a causal effect of the amount of home practice on cognition.

We also wanted to examine whether the level of spiritual well-being (SHALOM score) affects the effect of MBSR intervention. The SHALOM score did not correlate with the effect of MBSR intervention on cognition, depressive symptoms or anxiety. In accordance with a similar study56 examining the effect of Kirtan Kriya meditation on mood and the cerebral blood flow (CBS) in patients with memory loss, the role of spirituality seems to be marginal. We examined the level of spiritual well-being at the baseline; therefore, we can conclude that this variable is not some kind of prerequisite to profit from MBSR. The question of whether the observed effect of MBSR on depression or cognition could be related to the potential change of SWB during intervention remains open to further research.

Study Limits and Future Research

The main limitation of our study was the small sample size resulting in a difficult statistical analysis. The relatively high dropout rates could be also connected to the specifics of the MCI population, which may weaken the potential effect of MBSR. It is therefore appropriate to consider adapting this method to these patients, specifically, subjects with early MCI might be more adherent to the intervention. Also, providing subjects with short audio guides with instructions about home informal practice, e.g. mindful eating, might increase their adherence to the home practice. The adaptation may also involve an extension of time of the intervention - the results of other studies suggest that a longer than 8-week intervention period could support the expected intervention effect.41,117,121,122

At the MCI stage, it is often difficult to determine the etiology that causes cognitive deficit and various etiologies are typically associated with impairment in different cognitive domains.39 Therefore, another limitation is the possible different etiologies due to a lack of biomarker evidence. Future research with clearly defined etiologies could clarify the mechanism of MBSR and more precisely define the population that can benefit from MBSR.

As was mentioned earlier, the increased presence of physical difficulties in the elderly could be falsely interpreted as increased anxiety by the BAI questionnaire (items like “Wobbliness in legs”, “Numbness or tingling”, etc.), which could mantle the MBSR effect on pure anxiety symptoms. We also mentioned a higher mean level of depressive symptoms at the baseline, and that could have potentially highlighted the effect of MBSR on this variable. MBSR group had more hours of practice than cognitive training (because of the 6-hour retreat), that fact could potentially highlight the effect of MBSR.

Cognitive training is an active, effective treatment for cognition; however, its effect on depression, anxiety is unknown. We have included this intervention to address the possible placebo effect of any intervention associated with increased care and attention on these variables. However, our results do not support this assumption. The design of any future study should also include control of and motivation to post-intervention practice, and could also consider measuring spiritual well-being at V2 and V3 to better capture potential changes in this variable. As some studies reported,123 frequency of home practice during the intervention has a great impact on treatment effectiveness. In our study, we did not assess this potentially important variable in both MBSR and control group.

To sum up, a longer intervention with a larger sample, better practice control, clearly defined etiologies and adaptation to the needs of the elderly with MCI could potentially lead to better results. Longitudinal data could help answer the question about the protective potential of MBSR due to the risk of developing AN.

Future research and adaptations in this area may be inspired by other techniques based on meditation practice. Several studies have shown the positive effect of different meditation practices (Kirtan Kriya, Kundalini Yoga, etc.) on cognition and other variables of mental and physical health in MCI and in the population with subjective memory complaints.29−124−126

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that MBSR is generally well accepted by MCI subjects; however, cognitive decline might be negatively related to adherence to home practice and might require adjustments being made to the course. MBSR can decrease the level of depressive symptoms over the long term, but it is not more effective than standard cognitive training in the short term on general cognition in the MCI population. Nevertheless, there is a beneficial effect on psychomotor speed. MBSR also has a beneficial influence on resting monocyte activation. Assuming that depressive symptoms and chronic inflammation are considered risk factors of neurodegeneration, we can expect a possible protective effect of MBSR against the progression of cognitive decline derived from its potential to influence these risk factors. We assume that to prove a more pronounced effect on cognitive function, the intervention would need to be longer and adjusted to this specific population. Further longitudinal research could confirm and expand these findings in a larger population of elderly adults with MCI and assess the influence of a longer intervention program, the participants’ spirituality, and adaptation to the specific needs of the MCI population.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Alzheimer Foundation (Czech Republic). Supported by project no. LQ1605 from the National Program of Sustainability II (MEYS CR). This research was supported by the Grant Agency of Masaryk University, project number MUNI/A/1204/2017 and the European Social Fund and the European Regional Development Fund—Project MAGNET (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000492).

Disclosure

Andrej Jeleník reports being an MBSR teacher. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orgeta V, Qazi A, Spector A, Orrell M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiat. 2015;207(4):293–298. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu PH, Edland SD, Teng E, Tingus K, Petersen RC, Cummings JL. Donepezil delays progression to AD in MCI subjects with depressive symptoms. Neurology. 2009;72(24):2115–2121. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aa52d3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, et al. Inflamm‐aging: an evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908(1):244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Benedetto S, Müller L, Wenger E, Düzel S, Pawelec G. Contribution of neuroinflammation and immunity to brain aging and the mitigating effects of physical and cognitive interventions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giunta B, Fernandez F, Nikolic WV, et al. Inflammaging as a prodrome to alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao Q, Ang TF, DeCarli C, et al. Association of chronic low-grade inflammation with risk of alzheimer disease in ApoE4 carriers. JAMA netw open. 2018;1(6):e183597. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubio-Perez JM, Morillas-Ruiz JM. A review: inflammatory process in alzheimer’s disease, role of cytokines. Sci World J. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Page A, Garneau H, Dupuis G, et al. Differential phenotypes of myeloid-derived suppressor and T regulatory cells and cytokine levels in amnestic mild cognitive impairment subjects compared to mild alzheimer diseased patients. Front Immunol. 2017;8:783. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Page A, Lamoureux J, Bourgade K, et al. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil functions are differentially altered in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;60(1):23–42. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griciuc A, Serrano-Pozo A, Parrado AR, et al. Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron. 2013;78(4):631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradshaw EM, Chibnik LB, Keenan BT, et al. CD33 alzheimer’s disease locus: altered monocyte function and amyloid biology. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(7):848–850. doi: 10.1038/nn.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2551–2561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horrigan BJ. New studies support the therapeutic value of meditation. Explore. 2007;3(5):449–452. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciniak R, Sheardova K, Čermáková P, Hudeček D, Šumec R, Hort J. Effect of meditation on cognitive functions in context of aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:17. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurth F, Cherbuin N, Luders E. Reduced age-related degeneration of the hippocampal subiculum in long-term meditators. Psychiatry Res. 2015;232(3):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gard T, Hölzel BK, Lazar SW. The potential effects of meditation on age-related cognitive decline: a systematic review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1307:89. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(4):213–225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin. 2017;40(4):739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Brown CJ, Rose KM, Thompson-Heisterman A. The effects of meditation on perceived stress and related indices of psychological status and sympathetic activation in persons with alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/927509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalsa DS, Ashford JW. Stress, meditation, and alzheimer’s disease prevention: where the evidence stands. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):1–2. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell-Williams J, Jaroudi W, Perich T, Hoscheidt S, El Haj M, Moustafa AA. Mindfulness and meditation: treating cognitive impairment and reducing stress in dementia. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29(7):791–804. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newberg AB, Serruya M, Wintering N, Moss AS, Reibel D, Monti DA. Meditation and neurodegenerative diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1307(1):112–123. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newberg AB, Wintering N, Khalsa DS, Roggenkamp H, Waldman MR. Meditation effects on cognitive function and cerebral blood flow in subjects with memory loss: a preliminary study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(2):517–526. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant JA, Courtemanche J, Duerden EG, Duncan GH, Rainville P. Cortical thickness and pain sensitivity in zen meditators. Emotion. 2010;10(1):43. doi: 10.1037/a0018334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luders E, Clark K, Narr KL, Toga AW. Enhanced brain connectivity in long-term meditation practitioners. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells RE, Yeh GY, Kerr CE, et al. Meditation’s impact on default mode network and hippocampus in mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Neurosci Lett. 2013;556:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living, Revised Edition: How to Cope with Stress, Pain and Illness Using Mindfulness Meditation. Hachette UK; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. Hachette Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crane RS. Implementing mindfulness in the mainstream: making the path by walking it. Mindfulness. 2017;8(3):585–594. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0632-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss AS, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, et al. An adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction program for elders in a continuing care retirement community: quantitative and qualitative results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(4):518–538. doi: 10.1177/0733464814559411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creswell JD, Irwin MR, Burklund LJ, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(7):1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst S, Welke J, Heintze C, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on quality of life in nursing home residents: a feasibility study. Complement Med Res. 2008;15(2):74–81. doi: 10.1159/000121479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larouche E, Hudon C, Goulet S. Mindfulness mechanisms and psychological effects for aMCI patients: a comparison with psychoeducation. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;34:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siang-Ted K, Fam J, Feng L, et al. Mindfulness modulates biomarkers and cognition in elderly with mild cognitive impairment (MCI): a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;83:46. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.07.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong WP, Coles J, Chambers R, Wu DB, Hassed C. The effects of mindfulness on older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2017;1(1):181–193. doi: 10.3233/ADR-170031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanesco AP, King BG, MacLean KA, Saron CD. Cognitive aging and long-term maintenance of attentional improvements following meditation training. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement. 2018;2(3):259–275. doi: 10.1007/s41465-018-0068-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaliman P, Alvarez-Lopez MJ, Cosín-Tomás M, Rosenkranz MA, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;40:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Black DS, Slavich GM. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):13. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell. 2012;11(5):867–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong KL, Yeap WH, Tai JJY, Ong SM, Dang TM, Wong SC. The three human monocyte subsets: implications for health and disease. Immunol Res. 2012;53(1–3):41–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8297-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegler‐Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(3):584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jose SS, Bendickova K, Kepak T, Krenova Z, Fric J. Chronic inflammation in immune aging: role of pattern recognition receptor crosstalk with the telomere complex? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1078. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wells RE, Kerr CE, Wolkin J, et al. Meditation for adults with mild cognitive impairment: a pilot randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):642–645. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Astin JA. Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66(2):97–106. doi: 10.1159/000289116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE, Bonner G. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):581–599. doi: 10.1023/A:1018700829825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schure MB, Christopher J, Christopher S. Mind–body medicine and the art of self‐care: teaching mindfulness to counseling students through yoga, meditation, and qigong. J Couns Dev. 2008;86(1):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greeson JM, Webber DM, Smoski MJ, et al. Changes in spirituality partly explain health-related quality of life outcomes after mindfulness-based stress reduction. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):508–518. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9332-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Birnie K, Speca M, Carlson LE. Exploring self‐compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress Health. 2010;26(5):359–371. doi: 10.1002/smi.1305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moss AS, Wintering N, Roggenkamp H, et al. Effects of an 8-week meditation program on mood and anxiety in patients with memory loss. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(1):48–53. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaufman Y, Anaki D, Binns M, Freedman M. Cognitive decline in alzheimer disease: impact of spirituality, religiosity, and QOL. Neurology. 2007;68(18):1509–1514. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260697.66617.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hosseini S, Chaurasia A, Oremus M. The effect of religion and spirituality on cognitive function: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):76–85. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coin A, Perissinotto E, Najjar M, et al. Does religiosity protect against cognitive and behavioral decline in alzheimer’s dementia? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7(5):445–452. doi: 10.2174/156720510791383886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maruff P, Lim YY, Darby D, et al. Clinical utility of the cogstate brief battery in identifying cognitive impairment in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. BMC Psychol. 2013;1(1):30. doi: 10.1186/2050-7283-1-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheardova K, Vyhnalek M, Nedelska Z, et al. Czech Brain Aging Study (CBAS): prospective multicentre cohort study on risk and protective factors for dementia in the Czech Republic. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e030379. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mozolic JL, Long AB, Morgan AR, Rawley-Payne M, Laurienti PJ. A cognitive training intervention improves modality-specific attention in a randomized controlled trial of healthy older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(4):655–668. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Legault C, Jennings JM, Katula JA, et al., SHARP-P Study Group. Designing clinical trials for assessing the effects of cognitive training and physical activity interventions on cognitive outcomes: the Seniors Health and Activity Research Program Pilot (SHARP-P) study, a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith GE, Housen P, Yaffe K, et al. A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity: results from the Improvement in Memory with Plasticity‐based Adaptive Cognitive Training (IMPACT) Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(4):594–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santorelli SF, Kabat-Zinn J, Blacker M, Meleo-Meyer F, Koerbel L. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Authorized Curriculum Guide. Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society (CFM). University of Massachusetts Medical School; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gates NJ, Sachdev PS, Singh MA, Valenzuela M. Cognitive and memory training in adults at risk of dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. The impact of cognitive training and mental stimulation on cognitive and everyday functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suchá J. Cvičení paměti pro každý věk: testy na paměť a logiku. Portál; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suchá J. Skupinové hry pro cvičení paměti v každém věku. Portál; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bílková J. Kognitivní Trénink pro třetí věk: 100 cvičení pro rozvoj koncentrace, kreativity, paměti a verbálních dovedností. Grada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bezdicek O, Lukavsky J, Stepankova H, et al. The Prague Stroop test: normative standards in older Czech adults and discriminative validity for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2015;37(8):794–807. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2015.1057106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bezdicek O, Libon DJ, Stepankova H, et al. Development, validity, and normative data study for the 12-word Philadelphia verbal learning test [czP (r) VLT-12] among older and very old Czech adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;28(7):1162–1181. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2014.952666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tombaugh TN, Kozak J, Rees L. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14(2):167–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116(16):e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fisher J. Development and application of a spiritual well-being questionnaire called SHALOM. Religions. 2010;1(1):105–121. doi: 10.3390/rel1010105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marciniak R, Serek J, Sheardova K, Hudecek D, Hort J. SHALOM questionnaire psychometric characteristics of elderly Czech population. Cesk Psychol. 2017;61(3):230–244. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan J, Tsakok FH, Ow EK, et al. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of choral singing intervention to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk older adults living in the community. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:195. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sellami M, Gasmi M, Denham J, et al. Effects of acute and chronic exercise on immunological parameters in the elderly aged: can physical activity counteract the effects of aging? Front Immunol. 2018;9:2187. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, et al. Effects of exercise and horticultural intervention on the brain and mental health in older adults with depressive symptoms and memory problems: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial [UMIN000018547]. Trials. 2015;16(1):499. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1032-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Panza F, Frisardi V, Capurso C, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: possible continuum? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):98–116. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b0fa13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Monastero R, Mangialasche F, Camarda C, Ercolani S, Camarda R. A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(1):11–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Appleby BS, Oh ES, Geda YE, Lyketsos CG. The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(7):685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Larouche E, Hudon C, Goulet S. Potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease: an interdisciplinary perspective. Behav Brain Res. 2015;276:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress and levels of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and melatonin in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(4):448–474. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Matousek RH, Pruessner JC, Dobkin PL. Changes in the cortisol awakening response (CAR) following participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction in women who completed treatment for breast cancer. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bränström R, Kvillemo P, Åkerstedt T. Effects of mindfulness training on levels of cortisol in cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy for distressed survivors of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3119–3126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marcus MT, Fine PM, Moeller FG, et al. Change in stress levels following mindfulness-based stress reduction in a therapeutic community. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2003;2(3):63–68. doi: 10.1097/00132576-200302030-00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kox M, Stoffels M, Smeekens SP, et al. The influence of concentration/meditation on autonomic nervous system activity and the innate immune response: a case study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(5):489–494. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182583c6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rosenkranz MA, Davidson RJ, MacCoon DG, Sheridan JF, Kalin NH, Lutz A. A comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and an active control in modulation of neurogenic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;27:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bhasin MK, Dusek JA, Chang BH, et al. Relaxation response induces temporal transcriptome changes in energy metabolism, insulin secretion and inflammatory pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Black DS, Cole SW, Irwin MR, et al. Yogic meditation reverses NF-κB and IRF-related transcriptome dynamics in leukocytes of family dementia caregivers in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rodriguez JJ, Noristani HN, Verkhratsky A. The serotonergic system in ageing and alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;99(1):15–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bujatti M, Riederer P. Serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine metabolites in transcendental meditation-technique. J Neural Transm. 1976;39(3):257–267. doi: 10.1007/BF01256514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schutte NS, Malouff JM. A meta-analytic review of the effects of mindfulness meditation on telomerase activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;42:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yadav RK, Ray RB, Vempati R, Bijlani RL. Effect of a comprehensive yoga-based lifestyle modification program on lipid peroxidation. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;49:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schneider RH, Nidich SI, Salerno JW, et al. Lower lipid peroxide levels in practitioners of the transcendental meditation [registered sign] program. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(1):38–41. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim DH, Moon YS, Kim HS, et al. Effect of zen meditation on serum nitric oxide activity and lipid peroxidation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sinha S, Singh SN, Monga YP, Ray US. Improvement of glutathione and total antioxidant status with yoga. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1085–1090. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sharma H, Datta P, Singh A, et al. Gene expression profiling in practitioners of Sudarshan Kriya. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dusek JA, Otu HH, Wohlhueter AL, et al. Genomic counter-stress changes induced by the relaxation response. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martarelli D, Cocchioni M, Scuri S, Pompei P. Diaphragmatic breathing reduces postprandial oxidative stress. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(7):623–628. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gallegos AM, Hoerger M, Talbot NL, et al. Toward identifying the effects of the specific components of mindfulness-based stress reduction on biologic and emotional outcomes among older adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(10):787–792. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, et al. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res. 2011;191(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, et al. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:48–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]