Abstract

Hypertension is a leading cause of stroke and dementia, effects attributed to disrupting delivery of blood flow to the brain. Hypertension also alters the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a critical component of brain health. Although endothelial cells are ultimately responsible for the BBB, the development and maintenance of the barrier properties depend on the interaction with other vascular-associated cells. However, it remains unclear if BBB disruption in hypertension requires cooperative interaction with other cells. Perivascular macrophages (PVM), innate immune cells closely associated with cerebral microvessels, have emerged as major contributors to neurovascular dysfunction. Using 2-photon microscopy in vivo and electron microscopy in a mouse model of angiotensin-II hypertension, we found that the vascular segments most susceptible to increased BBB permeability are arterioles and venules >10μM and not capillaries. Brain macrophage depletion with clodronate attenuates, but does not abolish, the increased BBB permeability in these arterioles where PVM are located. Deletion of angiotensin-II type-1 receptors (AT1R) in PVM using bone marrow chimeras partially attenuated the BBB dysfunction through the free radical-producing enzyme Nox2. In contrast, downregulation of AT1R in cerebral endothelial cells using a viral gene transfer-based approach prevented the BBB disruption completely. The results indicate that while endothelial AT1R, mainly in arterioles and venules, initiate the BBB disruption in hypertension, PVM are required for the full expression of the dysfunction. The findings unveil a previously unappreciated contribution of resident brain macrophages to increased BBB permeability of hypertension and identify PVM as a putative therapeutic target in diseases associated with BBB dysfunction.

Keywords: Perivascular macrophages, Angiotensin II, Schlager mouse, 2-photon microscopy, Blood-Brain Barrier, Brain, Cerebral Circulation, Cerebrovascular, Cognitive Impairment

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension affects nearly 1/3 of the world population and has emerged as a global health threat1. Despite the benefits of anti-hypertensive therapy, the burden of disease caused by hypertension remains substantial, especially for brain diseases2, 3. Hypertension is a leading risk factor not only for stroke and cognitive impairment caused by vascular factors, but also for Alzheimer’s disease4. Cerebral blood vessels are a major target of hypertension5, 6. Thus, hypertension is the leading cause of the microvascular alterations underlying subcortical white matter damage (small vessels disease), a common cause of cognitive impairment7. The mechanisms of the cerebrovascular damage induced by hypertension are not fully understood. Although hypertension is well known to disrupt neurovascular function and impair the delivery of blood flow to the brain5, 6, evidence in humans implicates alterations of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) rather than blood flow in the cognitive dysfunction8–10. However, much less is known about the molecular and cellular bases of the BBB disruption in hypertension and their link to cognitive impairment11.

The BBB is a unique feature of the cerebral circulation that serves to regulate the traffic of molecules in and out of the brain12. Adjoining cerebral endothelial cells are sealed by tight junctions (TJ) that prevent the paracellular passage of molecules, and, owing to the expression of the fatty acid transporter and inhibitor of transcytosis Mfsd2a, exhibit limited vesicular transport13–15. Endothelial cells also express a multitude of luminal and abluminal transporters that tightly regulate the molecular exchange between blood and brain12. Although endothelial cells are critical for the barrier properties of the cerebral circulation, the development and maintenance of the BBB depends on the interaction with other cells of the neurovascular unit, including astrocytes, pericytes, and perivascular cells16, 17. However, little is known on the crosstalk between endothelial cells and other neurovascular cells in the BBB dysfunction caused by hypertension.

It has long been known that hypertension alters the BBB, but most studies have focused on acute blood pressure (BP) elevations which result in damage to the vascular wall especially in venules11. Other studies have examined the effect of agents involved in human hypertension, such as angiotensin II (Ang II), on permeability indices in endothelial cell cultures18–20. Thus, a complete picture of the cellular mechanisms by which hypertension, especially when long lasting, alters the BBB in vivo is lacking. Here we used chronic models of Ang II-dependent and genetic hypertension to examine the cellular bases of the increased BBB permeability. We found that slow-developing and sustained elevations in BP caused by Ang II induce TJ remodeling and increase transcytosis, alterations more pronounced in arterioles rather than capillaries. Although Ang II type-1 receptors (AT1R) on endothelial cells are essential to initiate the increase in BBB permeability, AT1R in perivascular macrophages (PVM), innate immune cells closely associated to cerebral arteriole21, 22, are critical for the full expression of the dysfunction through the free radical-producing enzyme Nox2. These findings reveal a previously unappreciated crosstalk between cerebral endothelial cells and perivascular innate immune cells in the pathobiology of the BBB, which may constitute a novel putative target for therapeutic intervention.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Detailed and expanded methods are found in the Online Supplement.

Mice and General surgical procedures

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medicine and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Studies were performed in a blinded fashion in male C57BL/6J mice (age 3-5 months, weight 25-30g; JAX, the Jackson Laboratory), in male BPN/3J (age 8-36 weeks as specified, JAX stock# 003004) and BPH/2J (age 8-26 weeks as specified, JAX stock# 003005). BPH/2J mice were originally generated through a two-way selection breeding program for high and low systolic BP, from a base population derived from an eight-way cross of inbred lines23, 24. The normotensive BPN/3J line, which is customarily used as control25, was randomly selected for breeding from the same base population23, 24. Bone marrow chimera experiments detailed below were performed on B6.129P2-Agtr1atm1Unc/J (AT1aR−/−, JAX stock# 002682) and B6.129S-Cybbtm1Din/J mice (Nox2−/−, JAX stock# 002365), both lines are congenic for C57BL/6, which were used as the wild-type control. AAV-BR1-iCre experiments detailed below were performed on B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm3(CAG-EYFP)HZE/J (Ai3 eYFP reporter, Stock# 007903), B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (Ai14 TdTomato reporter, Stock#007914), and homozygous C57BL/6N-Agtr1atm1Uky/J (AT1aRflox, Stock# 016211). AT1aRflox mice were crossed with vascular endothelium Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 (VE-Cad-CreERT2)26 mice for two generations to obtain F2 homozygous AT1aRflox carrying Ve-Cad-CreERT2. Female mice were not included in this study, as previous studies have shown that they are protected from this model of Ang II hypertension27, 28.

Osmotic minipump implantation

Osmotic minipumps containing vehicle (saline) or Ang II (600ng/kg/min) were implanted s.c. under isoflurane anesthesia as previously described25. Systolic BP was monitored in awake mice using tail-cuff plethysmography25. This dose of Ang II does not immediately raise BP, but increases BP slowly, starting at day 3 and continuing through the 14 days of infusion. This time-dependent rise in BP is consistent with the so called “slow-pressor” Ang II hypertension models29.

BBB permeability measurement

BBB permeability was assessed using fluorescein-dextran (FITC-dextran, MW 3 kDa; 100μl of 1% solution i.v.), as previously described25, 30. The amount of FITC-dextran (485nm excitation and 530 nm emission) was determined in duplicate using a fluorescence spectrophotometer, together with standards, and normalized to brain tissue weight.

Electron microscopy

Procedures for electron microscopy were identical to those previously described25, 31. Cortical microvasculature was examined using a Technai transmission electron microscope outfitted with a CCD camera system (AMT Advantage). Tight junction length and complexity (tortuosity ratio) were analyzed using MCID (Imaging Research). Tortuosity ratio was calculated as previously described31, where TJ length is divided by the diagonal of the rectangle that contains the length and height of the complete TJ. Endothelial vesicles were counted and normalized to endothelial area. Microvessels were defined as capillaries or arterioles based on the absence or presence of smooth muscle cells, respectively. Venules are not included in this analysis, as they cannot be reliably distinguished from pre-venular capillaries by electron microscopy32.

2-Photon microscopy

Optical access to brain was achieved through a long-term glass-covered cranial window implanted between lambda and the bregma (8 wide x 4 mm long), as previously described33. One week after osmotic mini-pump implantation, animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (1.5–2% in oxygen/nitrogen mix) and maintained at 37 °C rectal temperature. Unilateral craniotomies were performed over parietal cortex using a dental drill and sealed with a glass coverslip. All mice recovered for 7 days before in vivo imaging.

Imaging was performed on a commercial two-photon microscope (Fluoview FVMPE; Olympus) equipped with XLPlan N 25× 1.05 NA objective mounted on a piezo motor stage (P-725 PIFOC; PI). Excitation pulses came from a solid-state laser (InSight DS+; Spectraphysics) set at 830-nm wavelength. Signal was collected with an appropriate band-pass emission filters: 410- to 460-nm (SHG), 495- to 540-nm (FITC), and 575- to 645-nm (Texas Red) separated with a long-pass dichroic with a cutoff at 485nm and 570nm, respectively. Image stacks and movies were acquired through Fluoview software. Each hyperstack movie consists of 3 colors (SHG, FITC, Texas Red), 3 z-planes (0-, 50-, 100-μm) repeated for 10-minutes (200 frames/10 minutes) taken at a location where we could visualize branches from both pial arterioles and venules. To visualize vascular structure, plasma was labeled with 70kDa TexasRed-conjugated dextran via retro-orbital injection (50μl, 2.5% w/v, Invitrogen). To account for varying clarity of chronic cranial window due to surgical preparation, laser power was carefully adjusted to match a reference dataset. While acquiring the hyperstack movie, 3kDa FITC-conjugated dextran (30μl, 2.5% w/v, Invitrogen) was retro-orbitally injected under the microscope between first 10 to 25 seconds. Laser power was controlled to maintain fluorescence intensity at greater brain imaging depths, and our analysis was performed within the imaging depth previously established for this thinned-skull preparation34. All other digital imaging parameters, including gain and offset, for all three channels were kept constant across all animals. At the end of recording, 1- or 2-μm step z-stacks were taken from the thinned bone into the cortex at the same location for vessel structure and depth analysis. In case a second recording was needed, mice recovered for at least 2 days to clear the fluorescent dextran from the circulation.

For analysis, arterioles and venules were identified based on blood flow direction and vessel structure33, 35. To estimate the leakage of the FITC-dextran adjacent to the specific vessel segment, the time course of the fluorescent signal in a ROI (line: length 70μm-100μm) crossing the vessel of interest was extracted (Figure S4C). The line ROI was manually drawn across different vascular segments avoiding neighboring vessels using ImageJ software. First, the data we smoothed with a circular averaging filter in both time and space on the line ROI. Both edges of the vessel were detected at every time-frame to account for dilatation, constriction, and motion draft. Next, the vessel wall thickness was estimated and defined as the reduction in fluorescent signal adjacent to the intravascular signal (Figure S4C). Then, the extravascular signal was calculated as the average of the fluorescence outside the vessel wall over 10 min within a ROI of a prespecified length. In preliminary experiments a difference in the kinetics of the leakage depending on the vessel size was noticed. To account for such differences, the length of the ROI was adjusted based on the vessel diameter according to a linear logarithmic fit generated from manual analysis on a subset of arterial vessels with apparent border line acquired from the Ang II mice cohort (Figure S4D,E). Among two fluorescent intensity signals obtained per vessel, the lower intensity was chosen to plot. Finally, the depth of each measurement was calculated from the 3D stack taken at the end of recording as the distance between the end of the SHG signal in the bone and the vessel of interest. All images were processed using ImageJ, and the all analyses were performed with MATLAB. Vessels with diameters less than 10μm were classified as capillaries, and vessels with diameters greater than 10μm were classified as arterioles or venules based on direction of blood flow.

Bone marrow transplant

As previously described25, whole-body irradiation was performed on 6-week-old male mice with a lethal dose of 9.5 Gy of γ radiation using a 137Cs source (Nordion Gammacell 40 Exactor). Eighteen hours later, BM cells (2 × 106, i.v.) isolated from donor C57BL/6, B6.129P2-Agtr1atm1Unc/J (AT1aR−/−, JAX stock# 002682), or B6.129S-Cybbtm1Din/J mice (Nox2−/−, JAX stock# 002365) were transplanted in irradiated mice. Mice with transplanted BM cells were housed in cages with Sulfatrim diet for the first 2 weeks.

Cerebral endothelial knockdown of AT1aR

Seven-ten week-old C57BL/6J, B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm3(CAG-EYFP)HZE/J (Ai3 eYFP reporter, Stock# 007903), B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (Ai14 TdTomato reporter, Stock#007909), and C57BL/6N-Agtr1atm1Uky/J (AT1aflox, Stock# 016211) mice were administered 1.8x1011 VG in 100μL sterile PBS of AAV-BR1-iCre36 (AAV-NRGTEWD-CAG-iCre). Ang II pumps were implanted three weeks after AAV-BR1-iCre administration.

Statistics

Sample size was determined according to power analysis. Animals were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, and analysis was performed in a blinded fashion. After testing for normality (Bartlett’s test), intergroup differences were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test for single comparison, or by 1-way ANOVA (Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) or 2-way ANOVA (Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test), as appropriate and indicated in the figure legends. If non-parametric testing was indicated, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction was used. Statistical tests through the manuscript were performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad). 2-photon and electron microscopy statistics were performed using MATLAB and/or R. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and differences were considered statistically significant for p less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Ang II hypertension increases BBB permeability and alters endothelial ultrastructure in arterioles more than capillaries

First, we sought to examine the impact of Ang II hypertension on BBB permeability and define the vascular segment(s) most affected by the disruption. To this end, we used administration of Ang II for 14 days with osmotic minipumps (slow-pressor Ang II hypertension), a model thought to recapitulate key features of human essential hypertension29. BBB permeability was assessed at day 14 of Ang II infusion by the leakage into the brain of intravenously administrated FITC-dextran (M.W. 3kDa)25. Ang II infusion increased BP (Figure 1A) and brain extravasation of FITC-dextran quantified by spectrophotometry in brain homogenates (Figure 1B, p<0.0001). Brain imaging using 2-photon microscopy33 confirmed the vascular leakage of FITC-dextran into the cerebral cortex (Figure 1C, see Figure 3 for quantification). The BBB dysfunction was not related to the increase in BP induced by Ang II, because the extravasation was not suppressed by preventing the BP increase with antihypertensive drugs37, 38 (Figure S1A–B). The increased BBB permeability was associated with a reduction in the mRNA expression of key TJ proteins in cerebral microvascular preparations (Figure 1D), as well as marked suppression of Mfsd2a, a negative regulator of transcytosis13, 14. To assess the direct effect of Ang II treatment on the expression of TJ genes and TJ organization, as an index of BBB integrity, cerebral endothelial cell (transformed cell line, bEnd.3) cultures were exposed to Ang II (300nM for 24 hours). Following Ang II treatment, immunocytochemistry for the BBB protein claudin 5 and ZO1 suggested disorganization of TJs (Figure 1E). Furthermore, Ang II treatment also suppressed the mRNA expression of TJ proteins (claudin-5, ZO1, occludin), a change prevented by the Ang II AT1R inhibitor losartan (Figure S2) and implicating a direct effect of Ang II on endothelial AT1R.

Figure 1. Ang II hypertension enhances BBB permeability.

A. Slow-pressor Ang II increases systolic BP gradually (n=10; 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test; *p<0.001). B. Ang II hypertension enhances BBB permeability to 3kDa FITC-dextran (n=13-14; two-tailed unpaired t-test, *p<0.0001 vs saline). C. Ten minutes following 3kDa FITC-dextran administration, BBB leakage is visualized by 2-photon microscopy. Scale bar: 100μm. D. In cerebral microvascular preparation Ang II hypertension reduces the mRNA expression of the TJ proteins claudin-5 and occludin, but not ZO-1 (n=7-8). Expression of the vesicular transport regulator Mfsd2a is also suppressed (two-tailed unpaired t-test, claudin-5 n=10-12 *p=0.0275, occludin n=11-16 *p<0.0001, Mfsd2a n=11-12 *p=0.0002). E. In cerebral endothelial cell cultures, Ang II treatment (300nM; 24 hours) disrupts TJ as reflected by claudin-5 (green) internalization and ZO-1 (magenta) disorganization. Scale bar: 50μm. Abbreviations: A: arteriole; V: venule; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Figure 3. PVM depletion attenuates BBB permeability in cerebral microvessels larger than 30μm.

A. PVM depletion with liposomal clodronate (CLO) attenuates the breakdown of the BBB in Ang II hypertension (n=8-9; 2-way ANOVA; Liposome Factor p=0.0029, Ang II Factor p<0.0001, Interaction p=0.0054; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Saline-PBS vs Ang II-PBS p<0.0001, Saline-CLO vs Ang II-CLO p=0.0219, Ang II-PBS vs Ang II-CLO p=0.0007). B. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the vasculature labeled with 70kDa molecular weight Texas Red-dextran (magenta) and extravasated 3kDa molecular weight FITC-dextran (green). Extravascular and intravascular fluorescent signal is monitored over 10 minutes at the yellow line drawn on the vascular reconstruction above. C. Representative 2-photon images taken 5 minutes after injection of FITC dextran showing that BBB leakage in Ang II hypertension is prevented by PVM depletion. Scale bar is 100μm. D. Scatter of individual measurements plotting mean of extravascular signal intensity over 10 minutes versus depth from the surface of the brain. Top panels represent arterioles, and bottom panels venules; the diameter of the symbols (circles) is proportional to vessel diameter. Lines and shading indicate regression fit (logarithmic conversion on intensity axis) with 95% confidence interval. Multiple comparison test (95% confidence ANCOVA) was conducted between linear fit models (n=91-136; Artery: *p<0.01 vs Saline-PBS, #p<0.01 vs Ang II-PBS; Vein: *p<0.01 vs Saline-PBS, Ang II-PBS vs Ang II-CLO p=0.0687). E. Mean extravascular signal was compared over microvascular diameters in the first 60μm below the surface of the brain. Ang II hypertension does not enhance leakage of FITC-dextran in capillaries (2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.1562, Liposome Factor p=0.5159, Ang II Factor p=0.7333). Ang II hypertension enhances leakage of FITC-dextran in arterioles, which is attenuated by PVM depletion (2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0786, Liposome Factor p=0.0014, Ang II Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Saline-PBS vs Ang II-PBS p=0.0001, Ang II-PBS vs Ang II-CLO p<0.0001).

Next, we used electron microscopy to gain insight into the ultrastructural bases of the BBB dysfunction, focusing on TJ morphology and transcytosis, and to determine if the alterations were present in capillaries and arterioles. Venules were not examined because they cannot be reliably identified by electron microscopy32. Consistent with the downregulation of TJ proteins, Ang II led to significant TJ remodeling, as evidenced by a reduction in TJ length and tortuosity, a measure of complexity linked to BBB permeability31, 39 (Figure 2A–C). The reduction in TJ length was more pronounced in arterioles (−33.8 ± 3.7%) than in capillaries (−17.85 ± 4.0%, p=0.0341). The reduction in TJ tortuosity was also correlated with microvascular diameter, being greater in larger microvessels (Figure S3A–B). Cerebral endothelial cells are characterized by minimal transcytosis as reflected by the small number of cytoplasmic vesicles compared to other vascular beds12. Accordingly, in saline-treated mice we found a relatively low number of endothelial vesicles, both in capillaries and arterioles (Figure 2D). Ang II hypertension induced a marked increase in endothelial vesicle density. Surprisingly, the increase was correlated with vessel diameter (Figure 2E; p=0.0025), being significantly more pronounced in arterioles (+246.1 ± 20.8%) than in capillaries (+114.1 ± 12.0%, p=0.0124). Thus, Ang II hypertension affects both endothelial TJ and vesicular transport and has a greater impact on arterioles than in capillaries.

Figure 2. Ang II hypertension induces tight junction remodeling and enhances endothelial vesicle density.

A. Electron micrographs of neocortical capillaries showing cerebral endothelial cells forming tight junctions (magenta outline) and containing endothelial vesicles (highlighted in orange and black arrows). Tight junction remodeling and increased vesicle density is observed in Ang II (right) vs saline (left) treated mice. Scale bar: 500nm. B. Tight junction length is reduced in both capillaries and arterioles in Ang II hypertension (Saline/Ang II: capillaries n=102, arterioles n=69/79; 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0509, Vessel Size Factor p=0.0039, Ang II Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Ang II vs Saline capillaries p=0.0422, arterioles p<0.0001, Saline capillaries vs Saline arterioles p=0.0050). C. Tortuosity ratio (see Methods) is reduced capillaries and arterioles in Ang II hypertension (Saline/Ang II: capillaries n=104/102, arterioles n=71/79; 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.4364, Vessel Size Factor p=0.0577, Ang II Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Ang II vs Saline capillaries p<0.0001, arterioles p<0.0001). D. Cerebral endothelial vesicle density increases in Ang II hypertension (Saline/Ang II: capillaries n=104/60, arterioles n=41/44; 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0001, Vessel Size Factor p=0.0100, Ang II Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Ang II vs Saline capillaries p<0.0001, arterioles p<0.0001, Ang II capillaries vs Ang II arterioles p<0.0001). E. Vesicle density increases with vessel diameter in Ang II hypertension. Lighter symbols indicate capillaries, and darker symbols indicate arterioles. Line and shading indicate linear regression fit with 95% confidence interval. Multiple comparison test (95% confidence ANCOVA) was conducted between linear fit models (Saline vs Ang II p=0.0025).

PVM depletion attenuates hypertension-induced FITC-dextran leakage in vessels larger than 10μm

Brain PVM are key mediators of the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in Ang II hypertension and are associated with vessels larger than 10μm25. To investigate the role of PVM in the breakdown of the BBB we examined the effect of depletion of PVM using liposome-encapsulated clodronate delivered into the cerebral ventricles (i.c.v.). This method depletes PVM and meningeal macrophages by 80%, without affecting microglia or blood leukocytes25, 40. Vehicle- or clodronate-encapsulated liposomes were administered 3 days prior to the start of Ang II or saline infusion. Clodronate treatment did not affect the increase in BP evoked by Ang II (Figure S4A), but significantly reduced the brain extravasation of FITC-dextran (Figure 3A).

Next, we utilized in vivo 2-photon microscopy to define the microvascular segment protected by PVM depletion. A thin-skull cranial window was implanted unilaterally over the parietal bone, using procedures previously demonstrated not to induce inflammatory changes in the underlying cortex33, 41, 42. One week later, Texas Red-dextran (70kDa) was injected i.v. to label plasma, and (4kDa) FITC-dextran was injected to assess BBB permeability. The differences in size and fluorescence excitation/emission between these tracers (490/525 vs. 596/615 nm) allowed us to identify at the same time blood vessels and extravasating dextran (Figure 3B). Individual arterioles, capillaries, and venules were identified based on vascular diameter and direction of flow33. The parenchymal accumulation of FITC-dextran was averaged over 10 minutes after injection, when intravascular and extravasated FITC-dextran reached a steady state (Figure 3C). At this time, the intravascular signal did not vary significantly among experimental groups in arteries, capillaries, or veins (Figure S4B), indicating consistent intravascular loading of the tracer. Ang II hypertension increased FITC-dextran leakage in both arterioles and venules (p<0.01), an effect that was more pronounced in superficial vessels (<60 μm from the pial surface; Figure 3C–D). PVM depletion markedly reduced FITC-dextran extravasation in arterioles, but a trend towards reduction was also observed in venules (p=0.0687; Figure 3D). Examination of FITC-dextran extravasation according to vessel size, revealed that PVM depletion attenuates the Ang II-induced leakage in arterioles larger than 10μm in diameter, the microvessels where the leakage is greatest (Figure 3E). In agreement with the EM data on vesicular density (Figure 2E), the magnitude of the BBB leakage induced by Ang II was correlated with vessel size (Figure S5), an effect prevented by clodronate. Thus, brain PVM contribute to the BBB dysfunction induced by Ang II hypertension in arterioles and venules larger than 10μm, which is consistent with their association with these vessels.

PVM depletion attenuates BBB permeability and cognitive dysfunction in BPH/2J mice with chronic hypertension

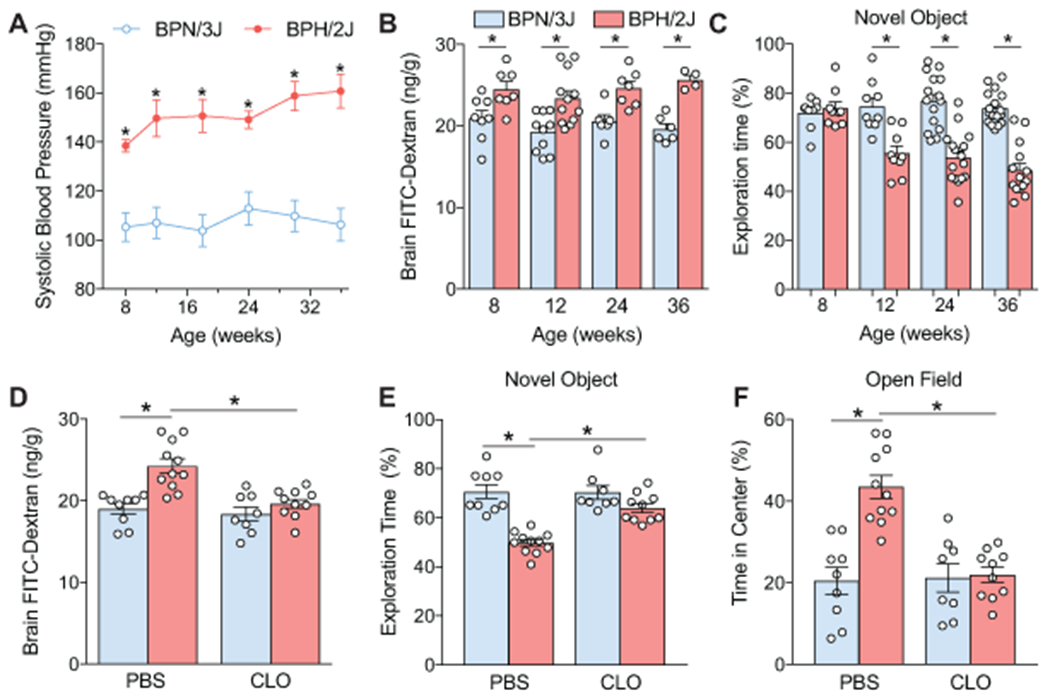

A limitation of the slow-pressor Ang II model is the short duration of the BP elevation, which does not adequately mimic the temporal profile of human hypertension and does not consistently lead to cognitive impairment25, 29. To overcome these drawbacks, we utilized BPH/2J mice, a model of spontaneous chronic hypertension23, 25. BPH/2J mice exhibit neurovascular dysfunction, which is driven by an increase in Ang II25, and, like the Ang II slow pressor model, is dependent on AT1R25. We found that BPH/2J mice have elevated BP and enhanced BBB permeability as early as 8 weeks of age compared to BPN/3J normotensive controls (Figure 4A–B). The BBB dysfunction preceded the development of cognitive impairment, first observed at 12 weeks when mice had difficulties distinguishing novel objects from familiar ones (novel object recognition test; Figure 4C). At this age, clodronate treatment did not lower BP (Figure S6A), but reversed the breakdown of the BBB (Figure 4D) and improved cognitive deficits. Thus, treatment with clodronate improved the ability of BPH/2J mice to discriminate between familiar and novel objects (Figure 4E; Figure S6B). At the open field test, BPH/2J mice showed hyperactivity and spent greater time exploring the central area of the open field, indicative of disinhibition, alterations also abrogated by PVM depletion (Figure 4F; Figure S6C). Therefore, PVM depletion rescues both BBB dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a model of chronic hypertension.

Figure 4. PVM depletion restores BBB integrity and improves cognitive function in chronically hypertensive BPH/2J mice.

A. BPH/2J mice have elevated systolic BP as early as 8 weeks of age compared to normotensive BPN/3J controls (n=7-10; 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test; *p<0.001). B. Enhanced leakage of FITC-Dextran is found in BPH/2J mice as early as 8 weeks of age (2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.6749, Age Factor p=0.2640, Genotype Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: 8 weeks n=7-8 *p=0.0299; 12 weeks n=10-12 *p=0.0010; 24 weeks n=6-7 *p=0.0189; 36 weeks n=6-4 *p=0.0017). C. BPH/2J mice spend less time exploring a novel object starting at 12 weeks, and progressing through 36 weeks of age (2-way ANOVA, Interaction p<0.0001, Age Factor p=0.0009, Genotype Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: 8 weeks n=9 p>0.9999; 12 weeks n=9 *p=0.0001; 24 weeks n=15-16 *p<0.0001; 36 weeks n=14-17 *p<0.0001). D. PVM depletion with liposomal clodronate (CLO) attenuates the BBB breakdown in BPH/2J mice (n n=8-11, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0118, Liposome Factor p=0.0013, Genotype Factor p=0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: BPN-PBS vs BPH-PBS *p<0.0001, BPH-CLO vs BPH-PBS *p=0.0003). E. PVM depletion restores cognitive deficits assessed by novel object recognition test in BPH/2J mice (n=8-11, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0022, Liposome Factor p=0.0030, Genotype Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: BPN-PBS vs BPH-PBS *p<0.0001, BPH-CLO vs BPH-PBS *p=0.0002). F. PVM depletion restores the aversion toward the center area at the open-field test without affecting total ambulatory time in BPH/2J mice (n=8-11, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0005, Liposome Factor p=0.0010, Genotype Factor p=0.0002; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: BPN-PBS vs BPH-PBS *p<0.0001, BPH-CLO vs BPH-PBS *p<0.0001).

AT1R in PVM are partially responsible for the Ang II-induced BBB dysfunction

The data presented above indicate that PVM are partly responsible for the BBB disruption induced by Ang II hypertension. Next, we sought to establish if AT1R in PVM, which play a key role in the neurovascular dysfunction of hypertension25, are also involved in the disruption of the BBB. To this end, we transplanted AT1aR−/− bone marrow into irradiated WT type mice (AT1aR−/−→WT) to repopulate the perivascular space with AT1aR−/− PVM, as previously demonstrated25. We also studied Nox2−/−→WT chimeras to investigate the role of Nox2, a free radical-producing NADPH oxidase downstream of AT1R which mediates Ang II-induced cerebrovascular oxidative stress25, 43. Three months after bone marrow transplantation, mice were implanted with Ang II minipumps and BBB permeability to FITC-dextran was assessed 14 days later. WT→WT chimeric mice did not exhibit baseline alterations in BBB permeability to FITC-dextran (p>0.05 from naïve WT mice). Ang II infusion increased BBB permeability in WT→WT chimeric mice to the same extent as in naïve mice (Figures 1B and 5A–B;), indicating that although PVM in these mice are bone marrow-derived they are equivalent to resident PVM with respect to the effects of Ang II on the BBB. Deletion of either PVM AT1R or Nox2 partially attenuated the BBB dysfunction induced by Ang II (Figure 5A), an effect size similar to that seen with PVM depletion by clodronate (Figure 3A). To determine if AT1R and Nox2 in the host were involved in the BBB dysfunction, we generated WT→AT1aR−/− and WT→Nox2−/− chimeras to repopulate the perivascular space with AT1aR+/+ and Nox2+/+ PVM. WT→AT1aR−/− chimeras did not develop slow-pressor Ang II hypertension and did not exhibit the increase in BBB permeability induced by Ang II (Figure 5C–D). On the other hand, WT→Nox2−/− chimeras did not exhibit BBB dysfunction despite sustained hypertension (Figure 5C–D).

Figure 5. AT1R and Nox2 on PVM contribute to the BBB breakdown in Ang II hypertension.

A. Depletion of AT1R or Nox2 on PVM in AT1R−/−→WT or Nox2−/−→WT chimeras attenuates the BBB dysfunction in Ang II hypertension (n=8-12, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0275, Donor Genotype Factor p=0.0354, Ang II Factor p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Ang II vs Saline [WT p<0.0001, AT1R−/− p=0.0384, Nox2−/− p=0.0047], chimera-Ang II vs WT-Ang II [AT1R−/− p=.0037, Nox2−/− p=0.0047]). B. Depletion of AT1R or Nox2 in PVM on does not affect the hypertensive response to Ang II infusion over 14 days (n=8-10, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: *p<0.01 Ang II vs saline). C. Introducing AT1R+/+ or Nox2+/+ PVM via bone marrow transplantation in AT1R−/− or Nox2−/− does not induce opening of the BBB during Ang II hypertension (n=6-12, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p<0.0001, Recipient Genotype p<0.0001, Ang II p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: Ang II vs Saline WT p<0.0001, chimera-Ang II vs WT-Ang II [AT1R−/− p<0.0001, Nox2−/− p<0.0001]). D. WT→AT1R−/− mice do not develop hypertension during Ang II infusion, while WT→Nox2−/− have increased SBP during Ang II infusion except for a small attenuation at day 14 (n=6-12, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: *p<0.01 Ang II vs saline, #p=0.0392 WT→Nox2−/− Ang II vs WT→WT Ang II).

Brain endothelial AT1R initiate the opening of the BBB in Ang II hypertension

These observations in chimeric mice indicate that AT1aR in PVM are necessary but not sufficient for the full expression of the BBB dysfunction, suggesting involvement of AT1R also in the host. Since cerebral endothelial cells express AT1R and are exposed to circulating Ang II25, 43, we examined the role of AT1R in these cells. We utilized systemic delivery of a cerebral endothelial-cell specific adeno-associated virus (AAV-BR1-iCre)36, 44 to selectively downregulate AT1aR in cerebral endothelial cells in AT1aflox mice. First, we sought to verify the extent of viral transfection of cerebral endothelial cells and the vascular segment involved by delivering the virus to Ai14 ROSA26TdTomato reporter mice. Three weeks following viral delivery, we examined TdTomato (Td) expression in brain by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry45. Td expression was colocalized with the endothelial cell marker CD31 (Figure 6A). By flow cytometry, we found 55% of brain endothelial cells are Td+, compared to less than 1% microglia or brain macrophages (Figure 6B), attesting to the cell-type selectivity of the endothelial targeting. Td expression was not detected in the liver or kidney, either in endothelial cells or parenchyma (Figure S7). Using a second reporter mouse (Ai3 ROSA26eYFP) we confirmed the 50% endothelial transfection with AAV-BR1-iCre both in cortical and hippocampal vessels (Figure 6C). Importantly, we found less than 5% eYFP+ in endothelial cells of the dura mater, a structure containing extracerebral arteries46, 47, attesting to the specificity of the viral gene transfer to cerebral endothelial cells. To examine the extent of viral transduction in vessels of different size, we assessed the extent of the overlap between Td-tomato and the endothelial marker CD31 across the cerebral cortex. In vessels 10-50μm in diameter >73% of the CD31+ area was Td+ (Figure 6D), whereas in vessels larger than 50μm the colocalization was lower (54 ± 3%, p<0.001; Figure S8A), indicating high transduction efficiency in vessels of interest (<50μm).

Figure 6. Cerebral endothelial AT1R are necessary for the BBB breakdown in Ang II hypertension.

A. AAV-BR1-iCre (1.8x1011 VG) administered i.v. in Ai14 ROSA26TdTomato reporter mice induces Td-Tomato expression (magenta) overlapping with the endothelial-specific marker CD31 (green). B. Flow cytometry data showing that AAV-BR1-iCre induces recombination in endothelial cells (EC), but not microglia (MG) or brain macrophages (MΦ), attesting to the cell-type specificity of the viral transduction (n=3). C. Flow cytometry data demonstrating the specificity of AAV-BR1-iCre recombination in cortical (CTX) and hippocampal (Hipp) endothelial cells, but not in endothelial cells of the dura mater, which contains extracerebral vessels (n=3). D. AAV-BR1-iCre viral transduction maintains >75% efficiency in vessels larger than 50μm in diameter, but decreases in vessels >50μm. Percent of CD31+ endothelial area that is Td-Tomato + is plotted against vessel diameter. Line and shading indicate linear regression fit with 95% confidence interval. E. AAV-BR1-iCre (1.8x1011 viral genome; i.v.) induces a 40% reduction in agtr1a genomic DNA when administered to AT1Aflox mice (n=7, two-tailed unpaired t-test, *p<0.0001 vs WT + iCre EC). F. AT1R knockdown in cerebral endothelial cells prevents the breakdown of BBB in Ang II hypertension (n=7- 9, 2-way ANOVA, Interaction p=0.0009, Genotype p=0.0007, Ang II p<0.0001; Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test: WT + iCre Saline vs Ang II *p<0.0001; WT + iCre Ang II vs AT1Aflox + iCre Ang II p<0.0001).

In AT1aflox mice, AAV-BR1-iCre delivery achieved a 40-50% reduction in Agtr1a genomic DNA in brain endothelial cells without affecting agtr1a expression in microglia (Figure 6E). This downregulation of Agtr1a genomic DNA in cerebral endothelial cells was comparable to that observed in AT1aflox VE-Cad-CreERT2+ mice (Figure S9). An important limitation of the VE-Cad-CreERT2 model is that AT1aR is downregulated in all endothelial cells, not only cerebral endothelial cells, thus we selected to proceed with AAV-BR1-iCre delivery in AT1aflox mice to specifically target cerebral endothelial cells. Next, we tested the effect of cerebral endothelial knockdown of AT1R on BBB permeability during Ang II hypertension. AAV-BR1-iCre administration did not affect the development of hypertension either in WT or AT1aflox/ mice (Figure S8B). However, AAV-BR1-iCre-treated AT1aflox/ mice, were fully protected from the BBB disruption induced by Ang II (Figure 6F), demonstrating an essential role of microvascular endothelial AT1R in the BBB disruption.

DISCUSSION

We used pharmacological and genetic approaches to dissect the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the breakdown of the BBB in models of chronic hypertension. We found that Ang II hypertension induces morphological and molecular remodeling of TJ as well as increased vesicular transport, alterations more prominent in arterioles than capillaries. Consistent with the localization these ultrastructural changes, in vivo 2-photon microscopy confirmed greater leakage of an intravascular tracer in arterioles and demonstrated also leakage in venules, which could not be studied by electron microscopy. Depletion of PVM attenuated BBB leakage, an effect observed not in capillaries but only in microvessels larger than 10μm in diameter, where PVM are located. Deletion of AT1aR or Nox2 in PVM also attenuated the BBB dysfunction with an effect size comparable to that of PVM depletion. However, reconstitution of AT1aR in PVM did not re-establish the BBB dysfunction in AT1aR−/− mice, implicating AT1aR also in the host, particularly in cerebral endothelial cells which express AT1R and are exposed to circulating Ang II25, 43. Accordingly, using AAV-BR1-iCre in AT1aflox mice to target cerebral endothelial AT1aR, we found that downregulation of AT1aR specifically in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells prevents the BBB dysfunction in full. While these findings establish an essential role of cerebral endothelial AT1aR in initiating the BBB dysfunction in Ang II hypertension, they also reveal a previously unrecognized cooperative interaction between PVM and endothelial cells in the full expression of the dysfunction, particularly in parenchymal arterioles.

Previous studies on the effects of chronic hypertension on the BBB examined the extravasation of intravascular tracers in brain sections post-mortem48, 49 or by measuring the concentration of the tracer in brain homogenates25, 50, 51, so that the vascular site of the BBB extravasation could not be defined. Using in vivo 2-photon microscopy we were able to visualize in real-time the extravasation of the intravascular tracer in the different segments of the cerebral microcirculation. We observed that in Ang II hypertension the bulk of the tracer leaks out of arterioles and venules, an effect more marked towards the brain surface. Minor leakage was also observed in capillaries, although this was not affected by any of the treatments. The increased propensity of arterioles to extravasation is unlikely to be due to the more pronounced mechanical stress imposed by the BP elevation in upstream arterioles than in capillaries, since the BBB dysfunction persists if the BP increase is completely prevented. Although there are segmental differences in BBB tightness in the normal state52, 53, the proximity of arterioles to PVM, which express AT1R, is likely to make these vessels more susceptible to the action of blood-borne Ang II. As we have shown previously, in this model Ang II is elevated in blood but not brain, and circulating Ang II crosses the endothelial barrier through paracellular and transcellular routes, enters the perivascular space and induces vascular oxidative stress through Nox2 in PVM25. The reduction in BBB leakage seen with clodronate in vessels associated with PVM suggests that PVM play a major role in the dysfunction. Clodronate depletes 80% of brain macrophages, and thus we cannot rule out that their contribution may be underestimated due to the residual 20%. However, the observation that downregulating the AT1R in cerebral endothelial cells leads to a complete rescue, argues against the hypothesis that the BBB dysfunction in Ang II hypertension is solely PVM mediated. The present results provide evidence that this process depends on AT1aR in endothelial cells, since AT1aR downregulation prevents the BBB dysfunction. Therefore, our findings, collectively, suggest that circulating Ang II engages AT1R in cerebral endothelial cells leading to increased transcytosis and tight junction remodeling, which allows the peptide to gain access to the perivascular space and activate AT1R in PVM (graphical abstract). The resulting increase in Nox2-dependent vascular oxidative stress, in turn, enhances the endothelial dysfunction and BBB leakage.

Although AT1R have been implicated in the BBB dysfunction induced by Ang II, previous studies used global receptor knockouts or systemic administration of pharmacological antagonists so that the cellular localization of the receptors could not be established11, 48, 50. Here, using viral gene transfer to cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, we were able to demonstrate for the first time that endothelial AT1R are absolutely needed for the BBB alterations. In agreement with previous studies36, the receptor downregulation achieved with the AAV-BR1-iCre virus was not complete, but it was nevertheless sufficient to abrogate the BBB dysfunction in full. While we cannot rule out that the magnitude of the downregulation was underestimated, this finding suggests that there might be a threshold for the functional effects of the receptor knockdown to occur. How AT1R activation leads to increased endothelial permeability remains to be defined. However, AT1R activation leads to cytoskeletal changes through signaling pathways involving ROS and Rho kinase54, 55 resulting in TJ disruption and increased paracellular transport20. As shown here in vivo and also observed in human cerebral endothelial cells in vitro20, AT1R activation leads to downregulation of Mfsd2a resulting in increased vesicular transport. These endothelial changes are likely to enable the entry of circulating Ang II into the perivascular space25, leading to AT1R and Nox2 activation in PVM which, in turn, amplifies the BBB disruption. Of the two AT1R receptor subtypes found in mice, we focused on the role of AT1aR, since this subtype is necessary for the majority of the pressor response elicited by exogenous Ang II56, 57, and thus resembles the effect of the single AT1R in humans as there is no human counterpart to the murine AT1b subtype58. Although the physiological significance of the subtypes in mice remains unclear, they were found to be differentially expressed in the cerebral vasculature with AT1bR having higher expression in pial versus parenchymal vessels59. No difference in AT1aR expression between pial and parenchymal vessel was found59. Future studies are necessary to determine the physiological significance of these receptor subtypes and their distribution in the cerebral vasculature .

In contrast to Ang II slow-pressor hypertension, in BPH/2J mice with chronic hypertension PVM depletion abolished the BBB dysfunction completely, pointing to PVM as the main cell type initiating the dysfunction. The reasons for this difference between the two models remain to be fully elucidated. However, in BPH/2J mice Ang II signaling is elevated also in brain60 and, consequently, this peptide has immediate access to the PVM in the perivascular space. It is therefore not surprising that in this model the PVM is the main cell type driving the BBB dysfunction. Owing to the complexity of the genetic background of BPH mice, genetic studies and bone marrow chimeras cannot be used to provide further insight in the BBB dysfunction25. Nevertheless, considering the importance of brain Ang II in the neurohumoral dysfunction of human hypertension61, our finding that PVM are responsible in full for the BBB dysfunction and cognitive impairment in BPH/2J mice suggest a putative cellular target for counteracting the deleterious effects of hypertension and, as such, has great translational relevance.

A contribution of BBB dysfunction to cognitive impairment has been postulated in virtually all brain disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases12, 16. Breakdown of the BBB is detrimental as it may lead to the brain entry of potentially harmful plasma molecules, e.g., fibrinogen, and inflammatory cells, as well as to the aberrant transport and clearance of critical molecules, a process essential for maintaining the homeostasis of the cerebral microenvironment12, 62. Genetic mutations that alter the function of the BBB, such as JAM-3, Ocln, Mfsd2a, and Notch3, increase the risk of neurodegenerative and neurovascular diseases12. Interestingly, in animal models of neurodegeneration the BBB dysfunction precedes cognitive dysfunction, also attesting to its potential pathogenic role63, 64. Recent data suggest a similar temporal relationship in patients with early cognitive dysfunction at risk for AD65. These findings are in agreement with our results in BPH/2J mice, in which the BBB permeability is impaired as early as 8 weeks of age, and precedes the development of cognitive impairment, first observed at 12 weeks. Importantly, at this time the BBB dysfunction and cognitive deficits are rescued by PVM depletion, attesting to the potential therapeutic value of targeting PVM even if cognitive dysfunction is already present. However, in BPH/2J mice, as in the Ang II slow-pressor model, PVM depletion also improves endothelial vasomotor function and neurovascular coupling25, which could also contribute to ameliorate cognition by restoring cerebral perfusion. Another caveat is that clodronate, in addition to PVM, also depletes meningeal macrophages, but not choroid plexus macrophages25, 40. Therefore, a role of meningeal macrophages in the cognitive dysfunction cannot be ruled out. Thus, future studies will need to explore the relative contribution of the alterations in BBB permeability and hypoperfusion in the cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension, as well as the specific role of meningeal versus PVM.

PERSPECTIVES

We examined the cellular and molecular bases of the BBB dysfunction induced by hypertension. After establishing that Ang II hypertension increases BBB permeability through transcytosis and TJ remodeling, we discovered that depletion of brain macrophages restores the BBB by preventing tracer leakage in vessels larger that 10μm in diameter, which are associated with PVM. Importantly, PVM depletion in BPH/2J mice with chronic hypertension improved BBB integrity as well as cognitive function in full. The contribution of PVM to the BBB disruption is mediated by AT1R and Nox2-derived ROS, but their involvement alone is not sufficient. Rather, AT1R in endothelial cells are absolutely required to initiate the increase in BBB permeability. The data suggest that activation of endothelial AT1R by circulating Ang II initiates the BBB opening which is then amplified by Ang II entering the perivascular space and engaging AT1R on PVM. These findings reveal a previously unappreciated cooperative interaction between endothelial cells and PVM in the full expression of BBB dysfunction in Ang II hypertension. The crosstalk between endothelium and perivascular innate immune cells emerges as a critical effector in the neurovascular pathobiology of hypertension, and provides new insights on how to protect the BBB in hypertension and other diseases associated BBB dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

1). WHAT IS NEW

The data unveil a previously unappreciated contribution of brain resident macrophages to the increased BBB permeability of hypertension and identify these cells as a putative therapeutic target in diseases associated with BBB dysfunction

2). WHAT IS RELEVANT

The BBB has emerged as a major culprit in diseases associated with cognitive impairment. Understanding the mechanisms underlying BBB disruption in hypertension is critical to identify novel therapeutic targets to preserve brain health during hypertension.

3). SUMMARY

Endothelial AT1R is necessary to initiate the BBB disruption in hypertension, but AT1R and Nox2 in PVM are required for the full expression of the dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grant R37-NS089323 (CI), and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association 17POST33370064 (MMS). The support from the Feil Family Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

CI serves on the strategic advisory board of Broadview Ventures. The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. A global brief on hypertension : Silent killer, global public health crisis. World health organization. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mmHg, 1990-2015. Jama. 2017;317:165–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorans KS, Mills KT, Liu Y, He J. Trends in prevalence and control of hypertension according to the 2017 american college of cardiology/american heart association (acc/aha) guideline. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iadecola C, Gottesman RF. Neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124:1025–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1598–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santisteban MM, Iadecola C. Hypertension, dietary salt and cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:2112–2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iadecola C, Duering M, Hachinski V, Joutel A, Pendlebury ST, Schneider JA, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: Jacc scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3326–3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wardlaw JM, Makin SJ, Valdés Hernández MC, Armitage PA, Heye AK, Chappell FM, et al. Blood-brain barrier failure as a core mechanism in cerebral small vessel disease and dementia: Evidence from a cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:634–643 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Makin SD, Marshall I, Geerlings MI, de Craen AJM, et al. Cerebral blood flow in small vessel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:1653–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joutel A, Chabriat H. Pathogenesis of white matter changes in cerebral small vessel diseases: Beyond vessel-intrinsic mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131:635–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Silva TM, Silva RAP, Faraci FM. Endothelium, the blood–brain barrier, and hypertension., Girouard H, ed: In: Arterial hypertension and the brain as an end-organ target. Switzerland: Springer; 2016:155–180 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier: From physiology to disease and back. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:21–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Zvi A, Lacoste B, Kur E, Andreone BJ, Mayshar Y, Yan H, et al. Mfsd2a is critical for the formation and function of the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2014;509:507–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreone BJ, Chow BW, Tata A, Lacoste B, Ben-Zvi A, Bullock K, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability is regulated by lipid transport-dependent suppression of caveolae-mediated transcytosis. Neuron. 2017;94:581–594.e585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen LN, Ma D, Shui G, Wong P, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Zhang X, et al. Mfsd2a is a transporter for the essential omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid. Nature. 2014;509:503–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebner S, Dijkhuizen RM, Reiss Y, Plate KH, Agalliu D, Constantin G. Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135:311–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21:193–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleegal-DeMotta MA, Doghu S, Banks WA. Angiotensin ii modulates bbb permeability via activation of the at(1) receptor in brain endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:640–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillot FL, Audus KL. Angiotensin peptide regulation of fluid-phase endocytosis in brain microvessel endothelial cell monolayers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:827–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo S, Som AT, Arai K, Lo EH. Effects of angiotensin-ii on brain endothelial cell permeability via pparalpha regulation of para- and trans-cellular pathways. Brain Res. 2019:146353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faraco G, Park L, Anrather J, Iadecola C. Brain perivascular macrophages: Characterization and functional roles in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl). 2017;95:1143–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kierdorf K, Masuda T, Jordao MJC, Prinz M. Macrophages at cns interfaces: Ontogeny and function in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:547–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlager G, Sides J. Characterization of hypertensive and hypotensive inbred strains of mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1997;47:288–292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlager G Selection for blood pressure levels in mice. Genetics. 1974;76:537–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faraco G, Sugiyama Y, Lane D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Chang H, Santisteban MM, et al. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:4674–4689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitulescu ME, Schmidt I, Benedito R, Adams RH. Inducible gene targeting in the neonatal vasculature and analysis of retinal angiogenesis in mice. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1518–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marques-Lopes J, Van Kempen T, Waters E, Pickel V, Iadecola C, Milner T. Slow-pressor angiotensin ii hypertension and concomitant dendritic nmda receptor trafficking in estrogen receptor β-containing neurons of the mouse hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus are sex and age dependent. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:3075–3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marques-Lopes J, Lynch M, Van Kempen T, Waters E, Wang G, Iadecola C, et al. Female protection from slow-pressor effects of angiotensin ii involves prevention of ros production independent of nmda receptor trafficking in hypothalamic neurons expressing angiotensin 1a receptors. Synapse. 2015;69:148–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerman LO, Kurtz TW, Touyz RM, Ellison DH, Chade AR, Crowley SD, et al. Animal models of hypertension: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e87–e120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faraco G, Brea D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Wang G, Racchumi G, Chang H, et al. Dietary salt promotes neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction through a gut-initiated th17 response. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:240–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackman K, Kahles T, Lane D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Abe T, Capone C, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes post-ischemic blood-brain barrier disruption. J Neurosci. 2013;33:19579–19589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HdF The fine structure of the nervous system: The neurons and supporting cells. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koizumi K, Hattori Y, Ahn SJ, Buendia I, Ciacciarelli A, Uekawa K, et al. Apoe4 disrupts neurovascular regulation and undermines white matter integrity and cognitive function. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorand RD, Barkauskas DS, Evans TA, Petrosiute A, Huang AY. Comparison of intravital thinned skull and cranial window approaches to study cns immunobiology in the mouse cortex. Intravital. 2014;3:e29728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korbelin J, Dogbevia G, Michelfelder S, Ridder DA, Hunger A, Wenzel J, et al. A brain microvasculature endothelial cell-specific viral vector with the potential to treat neurovascular and neurological diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:609–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munzel T, Kurz S, Rajagopalan S, Thoenes M, Berrington WR, Thompson JA, et al. Hydralazine prevents nitroglycerin tolerance by inhibiting activation of a membrane-bound nadh oxidase. A new action for an old drug. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1465–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, et al. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ Res. 2014;114:616–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathiesen Janiurek M, Soylu-Kucharz R, Christoffersen C, Kucharz K, Lauritzen M. Apolipoprotein m-bound sphingosine-1-phosphate regulates blood-brain barrier paracellular permeability and transcytosis. eLife. 2019;8:e49405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polfliet MM, Goede PH, van Kesteren-Hendrikx EM, van Rooijen N, Dijkstra CD, van den Berg TK. A method for the selective depletion of perivascular and meningeal macrophages in the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drew PJ, Shih AY, Driscoll JD, Knutsen PM, Blinder P, Davalos D, et al. Chronic optical access through a polished and reinforced thinned skull. Nat Methods. 2010;7:981–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu HT, Pan F, Yang G, Gan WB. Choice of cranial window type for in vivo imaging affects dendritic spine turnover in the cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:549–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazama K, Anrather J, Zhou P, Girouard H, Frys K, Milner TA, et al. Angiotensin ii impairs neurovascular coupling in neocortex through nadph oxidase-derived radicals. Circ Res. 2004;95:1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan C, Lu NN, Wang CK, Chen DY, Sun NH, Lyu H, et al. Endothelium-derived semaphorin 3g regulates hippocampal synaptic structure and plasticity via neuropilin-2/plexina4. Neuron. 2019;101:920–937.e913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benakis C, Brea D, Caballero S, Faraco G, Moore J, Murphy M, et al. Commensal microbiota affects ischemic stroke outcome by regulating intestinal gammadelta t cells. Nat Med. 2016;22:516–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coles JA, Myburgh E, Brewer JM, McMenamin PG. Where are we? The anatomy of the murine cortical meninges revisited for intravital imaging, immunology, and clearance of waste from the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;156:107–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louveau A, Filiano A, Kipnis J. Meningeal whole mount preparation and characterization of neural cells by flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2018;121:e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biancardi VC, Son SJ, Ahmadi S, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Circulating angiotensin ii gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Hypertension. 2014;63:572–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Liao YJ, Onodera M, Huang CL, Miyanaka H, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption in the hypothalamus of young adult spontaneously hypertensive rats. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vital SA, Terao S, Nagai M, Granger DN. Mechanisms underlying the cerebral microvascular responses to angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Microcirculation. 2010;17:641–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang M, Mao Y, Ramirez SH, Tuma RF, Chabrashvili T. Angiotensin ii induced cerebral microvascular inflammation and increased blood-brain barrier permeability via oxidative stress. Neuroscience. 2010;171:852–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butt AM, Jones HC, Abbott NJ. Electrical resistance across the blood-brain barrier in anaesthetized rats: A developmental study. J Physiol. 1990;429:47–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilhelm I, Nyul-Toth A, Suciu M, Hermenean A, Krizbai IA. Heterogeneity of the blood-brain barrier. Tissue Barriers. 2016;4:e1143544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cerutti C, Ridley AJ. Endothelial cell-cell adhesion and signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2017;358:31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schreibelt G, Kooij G, Reijerkerk A, van Doorn R, Gringhuis SI, van der Pol S, et al. Reactive oxygen species alter brain endothelial tight junction dynamics via rhoa, pi3 kinase, and pkb signaling. Faseb j. 2007;21:3666–3676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliverio M, Best C, Kim H, Arendshorst W, Smithies O, Coffman T. Angiotensin ii responses in at1a receptor-deficient mice: A role for at1b receptors in blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F515–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O, et al. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1a angiotensin ii receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3521–3525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coffman T, Audoly L, Oliverio M. Review: Gene targeting studies of angiotensin ii type 1 (at1) receptors. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2001;2:S10–S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamasaki E, Thakore P, Krishnan V, Earley S. Differential expression of angiotensin ii type 1 receptor subtypes within the cerebral microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physio. 2020;318:H461–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jackson KL, Marques FZ, Lim K, Davern PJ, Head GA. Circadian differences in the contribution of the brain renin-angiotensin system in genetically hypertensive mice. Front Physiol. 2018;9:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forrester SJ, Booz GW, Sigmund CD, Coffman TM, Kawai T, Rizzo V, et al. Angiotensin ii signal transduction: An update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1627–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petersen MA, Ryu JK, Akassoglou K. Fibrinogen in neurological diseases: Mechanisms, imaging and therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:283–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blair LJ, Frauen HD, Zhang B, Nordhues BA, Bijan S, Lin YC, et al. Tau depletion prevents progressive blood-brain barrier damage in a mouse model of tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montagne A, Zhao Z, Zlokovic BV. Alzheimer’s disease: A matter of blood-brain barrier dysfunction? J Exp Med. 2017;214:3151–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D’Orazio LM, Pachicano M, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med. 2019;25:270–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.