Abstract

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide and perhaps the most puzzling and devastating of all human behaviors. Suicide research has primarily been guided by verbal theories containing vague constructs and poorly specified relationships. We propose two fundamental changes required to move toward a mechanistic understanding of suicide. First, we must formalize theories of suicide, expressing them as mathematical or computational models. Second, we must conduct rigorous descriptive research, prioritizing direct observation and precise measurement of suicidal thoughts and behaviors and of the factors posited to cause them. Together, theory formalization and rigorous descriptive research will facilitate abductive theory construction and strong theory testing, thereby improving the understanding and prevention of suicide and related behaviors.

Keywords: suicide, suicide theory, formal models

Why Do People Kill Themselves?

The problem of suicide has puzzled scholars for thousands of years. A person’s decision to live or die has been called the “fundamental question of philosophy” [1] and has been the focus of work by most major philosophers throughout history (e.g., Plato, Kant, Sartre, Locke, Hume). In the sciences, suicide presents a fundamental challenge to the fact that most human and animal behavior is motivated by an innate and ever-present drive for self-preservation and gene survival [2–4]. Despite centuries of scholarly consideration and, more recently, scientific investigation, we do not have a clear understanding of why people kill themselves. Whereas scientific advances have led to the significant decline of other once leading causes of death over the past 100 years (e.g., pneumonia, cancer, tuberculosis), the global suicide rate has remained stable for decades [5], with, for example, current rates in the U.S. identical to rates in the 1910’s [6,7]. Alarmingly, suicide is projected to be an even greater contributor to the global disease burden in the coming decades [8]. Overall, understanding this perplexing aspect of human nature is one of the greatest challenges facing psychology and related disciplines. Here we critically review current theories and research approaches used to understand suicide, and we propose new directions for future theory development and research that can lead to a clearer, mechanistic understanding of suicide.

A Brief History of Suicide Theories and Research

In virtually all new areas of scientific inquiry, our understanding grows with the advancement of scientific theories accompanied by rigorous data collection. Pre-Copernican astronomy gave way to a heliocentric model of the universe and preformationist views of human development were overturned by the theory of Mendelian inheritance. Suicide theory remains in the early stages of this developmental progression. The earliest models of suicide were extremely simplistic, each aiming to identify the factor explaining why people kill themselves. For instance, more than 100 year ago Durkheim suggested suicide results from problems with social factors (e.g., lack of belongingness)[9] whereas Freud proposed it resulted from anger at a loved one directed inward [10]. These early theories were largely proto-scientific, in that they were derived from observation or from data (e.g., rates of suicide), but their predictions were never tested empirically.

In the 1950s–1990s, armed with decades of clinical observation, researchers began proposing single psychological factors that they believed to be especially important in the development of suicide. Such factors were selected a priori and subjected to empirical scrutiny typically using case-control studies. For instance, Shneidman, Neuringer, and Beck proposed that psychological pain [11], cognitive rigidity [12], and hopelessness [13], respectively, are particularly important causal factors. These and other researchers found that these factors are indeed correlated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors [14].

Beginning in the 1990’s, drawing on the growing body of empirical research on suicide, scholars began to propose theories focused primarily on the idea of suicide as a means of escaping seemingly intolerable circumstances. For example, Baumeister [15] argued suicide was a means to escape aversive self-awareness, Linehan [16] proposed it was a means of relieving aversive emotions, and Williams [17] suggested it served to escape feelings of defeat and entrapment. Rather than focusing on single factors as the cause of suicide, these theories focused on the single psychological function of escape, and these too have garnered some empirical support [18].

The most recent generation of suicide theories suggest that suicide results not from one factor or function, but from the interactions among a small set of specific factors drawn from earlier theories. For instance, combining the work of Durkheim, Beck, and others, Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide [19,20] proposes that three specific psychological factors (i.e., lack of belonging, feeling like a burden, and hopelessness) are necessary and sufficient to create suicidal thoughts; and one additional psychological factor (i.e., the acquired capability for suicide) is necessary and sufficient to cause the transition from suicidal thoughts to a suicide attempt. This and other current theories of suicide [21,22] propose simple pathways to suicide via the interaction of a small set of psychological factors.

Need for a New Approach to Studying Suicide

Many theories of suicide have provided important insights about suicide. For example, Joiner stressed the influential idea that suicide requires overcoming a natural aversion to harming oneself and that certain experiences may reduce this aversion, resulting in the acquired capability to die by suicide [19]. However, these theories share a common limitation that severely limits their ability to advance the understanding of suicide: they are all verbal theories. Verbal theories are characterized by the use of natural language to specify all aspects of the theory. For example, verbal theories use words to specify how the theory components are related to one another and how they produce the phenomena of interest. Because natural language is inherently vague [23], these theories often contain hidden assumptions, unknowns, or shortcomings. For example, consider the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, the most influential and empirically tested suicide theory. The theory was initially presented in Joiner’s influential book "Why People Die by Suicide." Referring to perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, Joiner writes, “Either of these states, in isolation, is not sufficient to instill the desire for death. When these states co-occur, however, the desire for death is produced” ([19] p. 135). Here, Joiner explicitly posits that both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are required for suicidal thoughts to emerge. In contrast, the first and most highly cited journal article outlining this theory states that, "individuals who possess either complete thwarted belongingness or complete perceived burdensomeness will experience passive... suicidal ideation" ([20] p. 20, emphasis in original). This contradiction is easy to overlook given the imprecision of verbal theories, but it has critical implications for the theory's predictions.

Even without contradictions, the limited precision of language means that verbal theories are almost always underspecified [24–26]. For instance, there are numerous ways in which verbal theories can be interpreted and implemented, most of which will produce different predictions. For example, what is the strength of the effect of perceived burdensomeness on suicidal thoughts? Is this a linear or non-linear effect? What is the time scale on which these variables have their effect? Precisely how do thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness interact to produce suicidal thoughts. The precise answers to these and many other questions will determine whether and when we should expect to see suicidal thoughts and behavior. Without such answers, it is impossible to deduce what this verbal theory predicts about suicidal thoughts and behaviors with any precision or certainty.

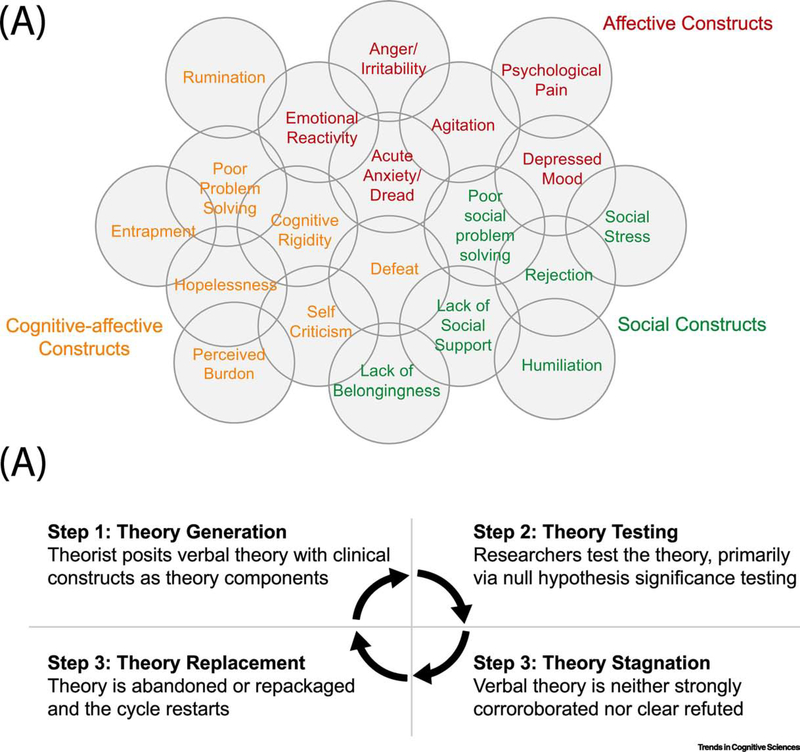

The inability to precisely determine what we should expect from a theory severely constrains our ability to corroborate and evaluate the theory. Verbal theories typically generate only general predictions (e.g., that perceived burdensomeness will be associated with suicidal thoughts) tested with null hypothesis significance tests. Yet, because most clinical constructs have non-zero intercorrelations, rejecting a null hypothesis often is simply a question of having a large enough sample. This problem is especially present in suicide theories, where theory components are generally a few of many intercorrelated and largely overlapping constructs that describe an adverse psychological state, such as psychological pain, loneliness, entrapment, hopelessness, or burdensomeness (Figure 1a). Given the large number of intercorrelated clinical constructs related to suicidal outcomes, null hypothesis significance tests are easy tests to pass, and, as a result, it is easy to corroborate almost any verbal theory made up of such constructs. Three decades ago, Meehl pointed out the problem of using intercorrelated variables (i.e., which he referred to as the “crud factor” [27]) and null hypothesis tests to evaluate verbal theories. He argued this approach leads theories to follow a predictable sequence: a new theory is met with a period of enthusiasm, followed by the publication of small effects that are consistent with the theory but do little to explicitly support or contradict the posited causal relationships. Interest in the theory eventually declines as it is neither strongly corroborated nor disconfirmed. Eventually the theory fades away and is replaced by another, similarly ill-defined one, restarting this sequence [27–29](Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Current approaches to the development of suicide theories. (a) Clinical constructs used in suicide theories are intercorrelated.

As Meehl [28,29] pointed out, most variables in a given domain, such as clinical psychology, tend to have some non-zero correlation, which he referred to as the “crud factor." Meehl’s focus was on correlations among distinct constructs. In suicide research, this problem is exacerbated by conceptual overlap among many constructs (e.g., lack of belongingness and an absence of social support). Note that many constructs displayed apart are conceptually overlapping and correlated (e.g., lack of belongingness and psychological pain [86]). (b) The life cycle of current approaches to suicide theory. Theories proceed through four stages. Step 1: a theory is generated with components that often are intercorrelated and conceptually overlapping with many other clinical constructs. Step 2: support for the theory is obtained often through the use of null hypothesis tests. Because constructs often have non-zero correlations with other clinical constructs, including suicidal thoughts and behavior, the null hypothesis is often rejected, particularly when statistical power is high. Step 3: theory testing continues to produce significant findings. However, these findings provide neither strong support nor unambiguous refutation of the theory. Further, they provide little guidance for how the theory might be modified and theoretical stagnation takes hold. Step 4: it becomes clear that the theory cannot advance understanding and it is replaced, leading the cycle to begin again. Notably, this cycle typically plays out over the course of decade or more, leading to slow progress in suicide theory.

These problems and patterns can be seen in the evolution of suicide theories. Consider again the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. A recent meta-analysis of 122 studies testing the hypothesized broad associations among the theory's components found that, as Meehl would predict, “effect sizes for these interactions were modest and alternative configurations of theory variables were similarly useful for predicting suicide risk.” ([30] p. 1313). This modest conclusion would almost certainly apply equally to all other existing suicide theories as well.

The fact that verbal theories provide only very broad predictions hinders actionable progress toward better understanding, predicting, and preventing suicide. Indeed, verbal theories invite stagnation because it is unclear how modifying one part of the theory changes the theory's predictions. Without modification, theories remain static for decades until individual researchers posit new theories with small elaborations, replacing those that came before. There is no easy way to incorporate changes based on new empirical data or novel proposals from collaborators. Together, the imprecision of verbal theories, the use of conceptually overlapping and highly correlated theory components, and the reliance on null hypothesis testing alone to test theory predictions have all contributed to slow progress toward understanding the causes of suicide (Figure 1b). To make progress, the field needs a framework and set of organizing principles for taking incremental steps needed to build a plausible, actionable theory of suicide.

New Directions for Advancing Suicide Theories

In the remainder of this article, we outline a set of principles that can guide efforts to build a better understanding of why people die by suicide. These principles fall in two broad domains. First, rather than developing theories of suicide composed of vague constructs and poorly specified associations, we must build suicide theories where (a) components are carefully defined and rooted in basic psychological science and (b) the relationships among components are precisely specified in the language of mathematics or a computational programming language. Second, to inform the initial generation and subsequent development of such theories, it will be necessary to conduct rigorous and rich descriptive research on both suicidal thoughts and behaviors and the theory components posited to give rise to suicidal phenomena.

Toward Formal Theories of Suicide

Theory Components with Precise Definitions, Grounded in Psychological Science

The first step in generating a theory of suicide is identifying the components the theorist believes cause suicidal thoughts and behavior. Currently, most components of suicide theories are imprecisely defined constructs either described by suicidal people or inferred from such descriptions by clinical researchers (e.g., psychological pain, hopelessness, lack of belonging). Although such clinically-derived components are critical to understanding suicide, three problems arise if we limit ourselves only to these components. First, these components are typically developed and used solely in clinical psychology, disconnecting suicide theory from broader psychological science. Second, there is often very low endorsement of these components in non-clinical samples, which means they cannot explain dynamic processes that move people in or out of clinical states that are precursors to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Third, many of the psychological constructs included in current theories of suicide are likely overlapping amalgamations of more basic processes [31]. For instance, “hopelessness” may represent decreased ability for imagining future positive events [32], imagining the future at all [33], difficulties with planning and problem-solving [34], fixed mindset [35,36], low self-efficacy [37] or include other constructs. Mental disorders are similarly highly heterogenous and conceptually complex amalgamations of more basic processes [38,39]. This blend of multiple processes under one broad construct likely contributes to the high intercorrelations among clinical constructs, obscures which of the underlying basic processes are related to suicide (and which are not) and makes it difficult to link to other units of analysis, such as environmental or neural processes.

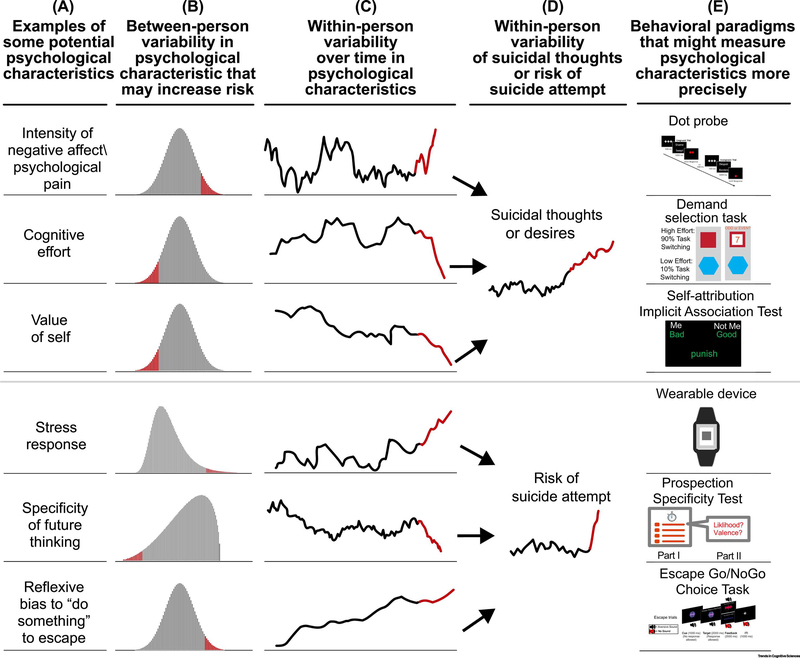

One organizing principle that can bring order to the long list of risk factors implicated in suicidal thoughts and behavior is to work from the assumption that suicide results from the dynamic interaction of multiple evolutionarily adaptive processes (Figure 2). For example, the stress response prepares us for fight or flight behaviors, risk-taking can promote exploration, prospection allows for simulating novel future events and self-criticism may allow for reflection and adjusting behavior. Some people have trait-level tendencies to experience extreme forms of these adaptive processes. At certain times, these tendencies interact with each other and with the current environment to create psychological states that can produce maladaptive behavior, such as suicide. From this perspective, suicide need not be caused by idiosyncratic dysfunctional psychological processes but may also arise from interactions among otherwise adaptive processes, perhaps operating at extreme ends of a spectrum. For example, it may be adaptive that during states of high negative affect, resources for cognitive effort became less available, self-reflection becomes more automatic and there is a push to "do something" to escape the negative affect [40]. However, in their most extreme forms, some combinations of these adaptive processes may interact to increase risk of suicidal thinking (e.g., a state of high stress and emotion, self-criticism and an absence of effective emotion regulation strategies); whereas others may interact to increase risk of acting on suicidal thoughts (e.g., a state of acute distress, a reflex to alleviate pain urgently, coupled with narrowing of time such that future consequences are less salient).

Figure 2. New approach to selecting components for suicide theory and constructs for suicide research.

Past research largely has translated clinically observed subjective psychological experiences (e.g., sadness, loneliness, hopelessness) into self-report scales and has shown that people with suicidal thoughts/behaviors tend to report higher levels of those experiences. A more promising approach is to conceptualize suicide as resulting from the interaction of dysfunctions in multiple evolutionarily adaptive domains. Column A contains sample constructs from adaptive domains. For instance, it is adaptive to experience physical and psychological pain; however, people at the high end of the distribution on tendency to experience psychological pain will be at elevated risk for suicide in general (Column B), and especially during periods when pain is especially elevated (Column C). More precise and repeated measurement of pain using methods from psychological science (Column E) will help us better understand how, why, when, and for whom suicidal thoughts and behaviors emerge.

Researchers may identify these basic building blocks of a suicide theory either by working from the bottom-up by beginning with basic psychological science constructs (e.g., a basic drive to escape aversive stimuli [41]), or working from the top-down, separating vague constructs from clinical psychology into constituent, basic psychological constructs (e.g. the fuzzy “distress tolerance” [42] construct that may be clarified by focusing on basic processes associated with urgent efforts to escape aversive states [40]). The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework, which has identified several well-defined constructs relevant to suicide, may be a fruitful source of such constituent components [43]. In determining these components, it may be useful to focus on those that vary in the general population and are amenable to objective measurement in behavioral paradigms (e.g., [40], but see [44,45] for work demonstrating measurement difficulties with behavioral paradigms). Regardless of the measurement approach (e.g., self-report, behavioral, etc.), it is crucial that, whatever components are chosen, they are characterized as precisely as possible.

Associations Among Theory Components that are Formalized

Theories are most helpful when they accurately describe the causes of real-world phenomena and facilitate their prediction and effective manipulation. If we can identify the mechanistic causes of why people think about suicide and attempt suicide, we could, in principle, both predict suicidal outcomes as well as target or guard against those causes directly. For the reasons mentioned previously, verbal theories are limited in their ability to provide mechanistic understanding, produce precise predictions, and inform new potential interventions. We believe that the next generation of suicide theories should be instantiated as mathematical models (i.e., theories expressed in the language of mathematics, such as differential equations) or computational models (i.e., theories expressed in a computer programming language). Mathematical and computational models have been used for over 50 years [46] to advance understanding across an array of scientific fields, [47] including some relevant to suicide, such as psychiatry [48] and cognitive science [49].

Mathematical and computational models share the key advantage of requiring precisely specified relationships between theory components. In doing so, these models overcome many of the aforementioned limitations of verbal suicide theories [24–26]. First, these models require theorists to be explicit and precise when specifying the relationships between theory components, for example, by specifying the strength and precise form of the relationship (e.g., linear vs. sigmoidal). Theorists must similarly specify exactly how theory components come together to produce suicidal phenomena, and the timescale over which theory components affect each other. Mathematical and computational models require specification of these and many other details that are omitted in verbal theories. Providing this level of detail often reveals assumptions, inconsistences, or differing interpretations that would go undetected in a verbal theory. Second, these models allow researchers to explicitly evaluate precisely what theory predicts. In a computational model this can be accomplished through simulations where we can observe how values for each component change over time as a result of the theory relationships. For example, a recent computational model of panic disorder was able to produce "panic attacks" through mathematically defined relationships between theory components of fluctuating physiological arousal (i.e., theorists generated values for this component to feed into the model), perceived threat, and homeostasis [50]. The fact that the model simulations produced a phenomenon similar to panic attacks (i.e., a spike of arousal and perceived threat arising from low level variations in arousal) does not ensure that the model is "correct," but does demonstrate that the theory can account for panic attacks. This ability to simulate theory-implied behavior, which is not possible with verbal theories, is especially important when theorizing about complex phenomena, like suicide, which arise from a web of interacting mechanisms, including physiological, behavioral, psychological and environmental factors. The behavior of even relatively simple systems is difficult to predict. Deriving the expected behavior of a complex system with feedback loops, non-linear effects, and multiple time scales from a verbal description alone is all but impossible.

By allowing researchers to determine precisely what a theory predicts, simulations provide a tool for examining what a theory can explain about the phenomena in question and where the theory falls short. At minimum, a model should be able to simulate outcomes consistent with phenomena it purports to explain. In well-developed theories, simulations from computational models can also prospectively predict complex real-world phenomena. Take, for example, Numerical Weather Prediction models. These models make weather predictions by modeling the effects from a large number of factors, ranging from solar radiation to geographical topography while also incorporating mechanisms (e.g., physical laws) and estimations of molecular processes [51,52]. Weather predictions (e.g., the path of a hurricane), come directly from model simulations (See Box 1 for how proposed models compare with other computational approaches). Analogously, formalizing theories of suicide will allow us to model the influence of a range of factors across units of analysis, including those with small effects (i.e., the psychological equivalent of molecular processes in weather models), and to use simulations to evaluate how well theories meet their intended use: to explain and predict suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Box 1. Proposed models within computational psychiatry.

Computational psychiatry uses computational methods to understand and predict psychiatric illness and related behaviors, such as suicide. There are two broad categories within computational psychiatry: data-driven and theory-driven approaches [69]. Data-driven research, such as machine learning, uses advanced statistics coupled with computationally intensive methods to uncover patterns in data. Within suicide research, data-driven approaches have mainly focused predicting suicide deaths and attempts from data sets containing tens or hundreds of variables, like electronic medical records [70]. Such prediction-focused approaches are useful [70–73], however, by themselves these approaches cannot, and are not intended to, provide mechanistic understanding. Therefore, they cannot, by themselves, discover the causes of suicide. In contrast, well developed theories can, in principle, not only predict suicide, but also inform how to interevene to reduce the likelihood of suicide in the future.

Theory-driven approaches use mathematical models of how psychological or neural processes are theorized to come together to produce behavior [48,69,74–78]. For example, in the 1950's mathematical models in psychology focused on specifying how operant conditioning experiments resulted in the acquisition and extinction of learned responses [79]. Later generations of these early models are now used in some computational psychiatry studies, where the goal is to use models to reveal specific aberrant psychological or neural processes affected in psychopathology [48,69,74–78].

Across many domains of science, theory-driven modeling with differential or difference equations that include time derivatives has been commonly used to advance the understanding of how dynamic systems (e.g., the weather, an ecosystem) vary over time. Although, there are several mathematical or computational frameworks one could use to develop psychological models, we suspect modeling with differential or difference equations is highly relevant to psychological and psychiatric theory. This is because these models can represent complex relationships among a variety of components and show how, together, they give rise to phenomena of interest, such as suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Dynamical systems modeling was first used in psychology decades ago [80] and others have promoted their use to better understand psychiatric issues [81], but the use of these models remains rare in clinical psychology. Similarly, although researchers have used non-linear dynamical systems to conceptualize suicidal processes [82–84] and guide analyses [82,83,85], there has been little effort to use these theory-driven dynamical models to advance theories of suicide.

Empirical Research that Guides, and is Guided by, Formal Theory

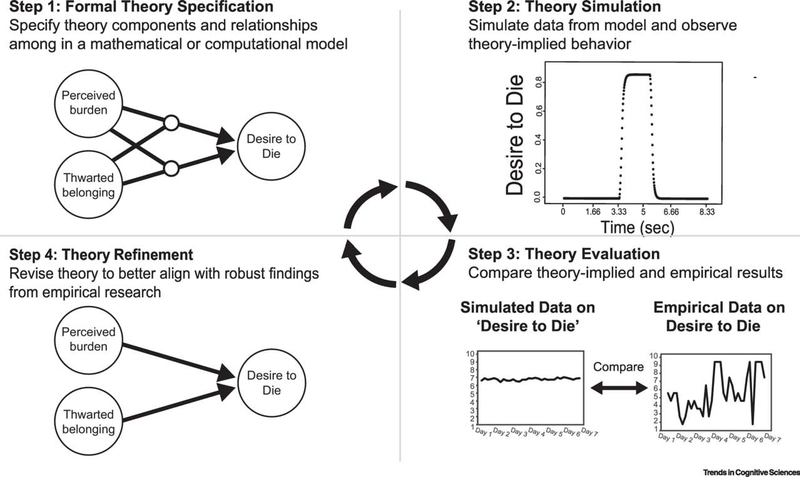

The development of formal theories of suicide requires an ongoing exchange between theory construction and rich, precise descriptive research. This exchange begins with generating a formal theory, forcing theorists to precisely specify the theory components and the relationships among them. This process often reveals gaps in understanding, where further empirical research is required. Thus, formal theories improve the efficiency of research by identifying empirical studies that will best inform the development of suicide theory, thereby making better use the field’s intellectual and financial resources. Once formal theories are generated, a cycle begins whereby theory-implied data from simulations are compared with empirical data, revealing what the theory can explain and what it cannot [53] (Key Figure 3). The theory is then modified, and theory-implied data are simulated to see whether the modified theory can account for additional phenomena, align better with empirical data or reveal new gaps in understanding that need to be addressed through empirical research. This exchange, where empirical research is guided by theory and theory is both informed by and evaluated against empirical research, offers an avenue for incremental but meaningful progress in suicide theory. Thus, in contrast with verbal theories, the corroboration and evaluation of formal theories guide incremental improvement [54] toward a goal of having models that can predict and prevent actual suicidal outcomes.

Figure 3. The life cycle of proposed formal theories using the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) [19,20] as an example.

Step 1: Formal theory specification. There were many possible ways to specify the verbal theory in a formal model. We first diagramed the theory, specifying that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness directly affect the desire to die and moderate each other's causal effects (i.e., the effect of one component on desire to die is stronger when the other is high). Step 2: Theory Simulation. We next used the computational model to closely examine the theory’s implied behavior over a brief time period. We set all components to zero. Successively, we increased perceived burdensomeness, then thwarted belongingness to one and then each consecutively back to zero. Due to the moderating effects, the model predicts that both causal components are required for the desire to die to increase. Their combined effect causes a rapid increase in desire to die. These results could inspire studies seeking to corroborate these effects. Step 3: Theory Evaluation. The results from theory implied “data” are compared to those from empirical data. We possessed data on one person’s reported desire to die, sampled 34 times over one week (unpublished data). We therefore simulated “desire to die” from the IPTS model sampled at the same frequency to assess how well our model captures the empirical phenomenon. The values of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness over time were drawn randomly from a normal distribution (M = 2.5, SD = 1.5). The simulated data shows far less variability than the empirical data; therefore, the model likely needs revision. Step 4: Theory Refinement. Discrepancies between the theory and robust empirical findings result in theory modification, bringing the theory more in line with empirical research. This revised theory is specified as a formal theory, restarting this cycle. Each cycle incrementally gives the theory more explanatory and predictive power.

Theory Development that is Open, Collaborative, and Cumulative

Formalizing theories makes them explicit and transparent. Accordingly, rather than individual theorists creating suicide theories that remain static for decades, formal models allow any researcher to make contributions to parts of the model in their area of expertise. A plausible mechanistic model of suicide will likely include components from multiple content areas and units of analysis, requiring contributions from a wide range of expertise. By encouraging collaborative development, formal theories could facilitate advancements in suicide theory over the course of years, rather than decades.

Toward More Descriptive and Efficient Empirical Research

Clearer Conceptualization and Measurement of Suicidal Phenomena

New directions in theory development will be most fruitful if we also pursue better definitions and measurement of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. A theory can only be as precise as the phenomena it is aiming to account for. For example, if we knew that, on average, suicidal thoughts tend to last approximately 30 minutes, then "suicidal thoughts" simulated in a computational model of suicide should demonstrate this property. Unfortunately, we do not understand many aspects of suicidal thoughts and behaviors nor is there even consensus on how to define these key constructs. Borrowing Tinbergen [55] and Kagan's [56] criticism about the field of psychology; in their haste to build models of suicide risk, researchers have jumped over the important step of carefully conceptualizing, operationalizing and describing the key dependent variables of interest. "Suicidal thinking," inherently fuzzy and ill-defined, could refer to having thoughts about causing one’s own death, an active desire to do so, mental images of engaging in a suicide attempt or something else.

This lack of consensus has been shown empirically: approximately 10% of people who endorse commonly used questions to assess “suicidal thoughts” later describe thoughts that researchers would not classify as such [57] (the problem is even worse for suicide attempts with 10–50% reporting behaviors not consistent with researchers' definitions [57–59]). Moreover, most existing measures of suicidal thinking combine myriad facets of suicidal thoughts (e.g., severity, duration, controllability) into an overall “suicidal thinking” score represented by an arbitrary metric (e.g., 0–30 points). Given that these different facets vary in their associations with, for example, future suicide attempts [60], aggregating these features into a single, arbitrary scale hinders understanding. Progress is unlikely without dedicated efforts to more clearly and consistently define and operationalize the key facets of suicidal thoughts and behaviors upon which theoretical and predictive models should be built. Achieving better operationalizations and measurement of key suicidal outcomes will likely require in-depth systematic descriptions of suicidal phenomena. In some cases – perhaps most – qualitative research will be needed to gain richer descriptions of such phenomena, which can be used to develop quantitative assessments with well-defined outcomes and more precise measurement.

Research that Observes and Measures Changes over Time

Traditionally, researchers have attempted to understand suicidal thoughts and behaviors using retrospective rating scales in which people report the presence or average level of suicidal thoughts over some extended period of time (e.g., past month). As a result, we have little understanding of the dynamics of suicidal thoughts and no ability to predict such thoughts. The use of retrospective rating scales is akin to using the previous months average rain fall to know whether it is going to rain this afternoon. Fortunately, the recent ubiquity of smartphones has facilitated high frequency, realtime, ambulatory longitudinal data collection, which have provided glimpses into how suicidal thoughts play out over hours. These methods have revealed that suicidal thoughts fluctuate rapidly over the course of the day [61,62]. Yet, many characteristics of suicidal thoughts over time are unknown, such as their dynamics over even shorter time scales, how long they persist, or what factors cause them to have higher intensity or longer duration. Most prior suicide research has focused on static factors measured at one time point. Instead, observing and measuring change over time is necessary to advance our understanding of key suicidal phenomena, such as the precise steps people take as they move from thinking about suicide to attempting suicide [63], as well as the interaction of psychological processes that result in these outcomes (Figure 2).

High-frequency, repeated data collection also permits researchers to examine suicidal thoughts and behaviors as they occur over time, within individuals. This research is critical because we cannot assume that group-level results (e.g., the cross-sectional correlation between perceived burdensomeness and suicidal thoughts across different individuals) will correspond to results from within-person analyses (e.g., the contemporaneous association between perceived burdensomeness and suicidal thoughts within a given individual)[64–66]. Thus, examining processes expected to cause an individuals' behavior requires within-person data. Such data allow researchers to examine the possibility that factors associated with suicidal thoughts and behavior vary from person-to-person. This possibility would have important implications for suicide theories (i.e., that the causes of suicide may also vary among people), which, until now, have assumed that the causes of suicide are the same across people.

Concluding Remarks

Suicide is among the most devastating global public health problems. The causes of such a complex and multidetermined behavior are not easily revealed. We have argued that two broad steps – formalizing suicide theories and conducting more rigorous descriptive research – are necessary to make meaningful progress understanding suicide. Some of these steps can be accomplished immediately whereas others will take longer. For example, formalizing a theory of suicide can be accomplished now, perhaps in collaboration with experts in mathematical and computational modeling [67]. As an illustration, we formalized the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Key Figure 3) and in doing so, encountered several unanswered questions, such as how, precisely, key constructs are related to suicidal outcomes. This process alone informs areas in need of further theory development and more precise empirical research. Descriptive research focusing on better characterization and measurement of key suicidal constructs can similarly occur immediately, as can measurement of key constructs and suicidal outcomes over time and within person.

It will take longer to determine the extent to which nomothetic models of suicide can be individualized and ultimately used in clinical practice with individual patients [68] (see Outstanding Questions). It will be similarly challenging to determine how best to precisely measure key independent variables that account for suicidal outcomes. In part, this is because of inherent limitations associated with precisely measuring psychological phenomena, particularly those that involve emotions. Yet, it is critically important that we continue to make progress. We believe moving toward the principles outlined here provides the greatest opportunity to advance the understanding of suicide and our ability to prevent it.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the critical components, drawn from psychological science, needed to generate a plausible computational theory of suicide? Are there components that apply broadly enough that they are able to account for most instances of suicidal thoughts and behaviors?

Given the many possible pathways individuals take to suicide, how can nomothetic theories of suicide best be used to understand and predict individual-level processes?

Given the difficulty of precisely measuring subjective states, can measurements of psychological constructs reliably inform the evaluation and ongoing development of formal theories? Although formal theories can advance understanding without precise measurement, they will be considerably more informative if they are well evaluated with precisely measured data.

What are the best ways to use empirical research to, inform, evaluate, and advance formal theories? There are at least two broad directions. First, researchers could focus on in-depth descriptive research focused on a part of a model. For example, focusing on precisely specifying a relationship in a formal theory (e.g., by manipulating one theory component and evaluating its effect on the other). However, this approach neglects the effects of the rest of the theory. Alternatively, researchers could focus on comparing predictions from the entire theory to empirical data. For example, qualitatively comparing known phenomena against simulations or comparing the results of statistical models run on simulated versus empirical data. Although promising, there are many unanswered questions in this approach, including determining when discrepancies between theory-implied and empirical data models is sufficiently large that it warrants theory modification.

How do we encourage and incentivize collaborative formal model building and development? One possibility is a website for sharing model code and materials, similar to sites in other scientific areas (e.g., https://www.comses.net/).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Due to scientific advances, there have been significant declines in many once leading causes of death over the past 100 years, yet global suicide rates have remained fairly stable for decades. The lack of progress understanding, predicting, and preventing suicide is due in part to the limitations of current scientific theories of suicide.

After providing a brief history of suicide theories, we argue that these theories are limited due to two fundamental factors: (1) they are imprecise, consisting of vaguely defined components and underspecified relationships among those components, precluding concrete theory predictions that could be tested, and (2) there is a lack of rigorous descriptive research that is necessary to inform the generation, testing and development of more precise theories.

We provide several guiding principles to address these limitations: focusing on the need to formalize theories as mathematical and computational models and to collect rigorous and intensive descriptive research on key suicidal outcomes and the factors posited to give rise to those outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to MKN (5U01MH116928 – 02), the Chet & Will Griswold Fund to MKN, the Tommy Fuss Fund to MKN and AJM and a NIMH Career Development Award (1K23MH113805 – 01A1) to DJR. We thank Shirley Wang and Daniel Coppersmith for helpful feedback and discussion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Camus A (1955) The myth of Sisyphus (O’Brien J Trans.), (Original work published 1942) Knopf Alfred A., Inc.

- 2.Wilson EO (1978) On human nature: Twenty-fifth anniversary edition, Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawkins R (1976) The selfish gene, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorenz K (1963) On aggression, Harcourt Brace.

- 5.Naghavi M et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 390, 1151–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter SB et al. (2006) Historical statistics of the United States: Millennial edition, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017), Underlying cause of death, 1999–2015 on CDC WONDER online database. [Online]. Available: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html [Accessed: 25-Sep-2017]

- 8.World Health Organization Global Health Estimates. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GHE_DthWBInc_Proj_2016-2060.xlsx [Accessed: 11-Jul-2019]

- 9.Durkheim É (1951) Suicide: A study in sociology (Spaulding JA & Simpson G trans), (Original work published 1897) Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freud S (1917) Mourning and melancholia. In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. 14 (Strachey J, ed), pp. 243–258, The Hogarth Press [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shneidman ES (1993) Suicide as psychache. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 181, 145–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuringer C (1964) Rigid thinking in suicidal individuals. J. Consult. Psychol. 28, 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT (1986) Hopelessness as a predictor of eventual suicide. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 487, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin JC et al. (2017) Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 143, 187–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumeister RF (1990) Suicide as escape from self. Psychol. Rev. 97, 90–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linehan M (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder, Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JMG (2001) Suicide and attempted suicide: Understanding the cry of pain, Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boergers J et al. (1998) Reasons for adolescent suicide attempts: Associations with psychological functioning. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 37, 1287–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joiner TE (2005) Why people die by suicide, Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Orden KA et al. (2010) The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol. Rev. 117, 575–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klonsky ED and May AM (2015) The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 8, 114–129 [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor RC and Kirtley OJ (2018) The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grice HP (1975) Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics Vol 3: Speech acts (Cole P. and Morgan JL, eds), pp. 41–58, Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smaldino PE (2017) Models Are Stupid, and We Need More of Them. In Computational Social Psychology (1st edn) (Vallacher RR et al., eds), pp. 311–331, Routledge [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewandowsky S and Farrell S (2010) Computational Modeling in Cognition: Principles and Practice, SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanneman RA et al. (1995) Discovering Theory Dynamics by Computer Simulation: Experiments on State Legitimacy and Imperialist Capitalism. Sociological Methodology 25, 1–46 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meehl PE (1990) Appraising and amending theories: The strategy of Lakatosian defense and two principles that warrant it. Psychol. Inq. 1, 108–141 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meehl PE (1990) Why summaries of research on psychological theories are often uninterpretable. Psychol. Rep. 66, 195–244 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meehl PE (1978) Theoretical risks and tabular asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the slow progress of soft psychology. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 46, 806–834 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu C et al. (2017) The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull. 143, 1313–1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett LF (2017) The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12, 1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor RC et al. (2015) Intrapersonal positive future thinking predicts repeat suicide attempts in hospital-treated suicide attempters. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 83, 169–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams JM and Broadbent K (1986) Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 95, 144–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock LR and Williams JMG (2001) Effective problem solving in suicide attempters depends on specific autobiographical recall. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 31, 386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroder HS et al. (2017) Growth mindset of anxiety buffers the link between stressful life events and psychological distress and coping strategies. Pers. Individ. Differ. 110, 23–26 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dweck CS (2008) Mindset: The new psychology of success, Ballantine Books. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czyz EK et al. (2016) Coping with suicidal urges among youth seen in a psychiatric emergency department. Psychiatry Res. 241, 175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fried EI et al. (2015) The differential influence of life stress on individual symptoms of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 10.1111/acps.12395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Fried EI and Nesse RM (2015) Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. Journal of Affective Disorders 172, 96–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millner AJ et al. (2019) Suicidal thoughts and behaviors are associated with an increased decision-making bias for active responses to escape aversive states. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 128, 106–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millner AJ et al. (2018) Pavlovian control of escape and avoidance. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 30, 1379–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vujanovic AA et al. (2017) Posttraumatic stress and distress tolerance: Associations with suicidality in acute-care psychiatric inpatients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 205, 531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glenn CR et al. (2017) Understanding Suicide Risk Within the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Framework: Insights, Challenges, and Future Research Considerations. Clinical Psychological Science 5, 568–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedge C et al. (2018) The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behav Res Methods 50, 1166–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enkavi AZ et al. (2019) Large-scale analysis of test–retest reliabilities of self-regulation measures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 5472–5477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tocher KD (1963) The art of simulation, English Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humphreys P (2004) Extending ourselves: Computational science, empiricism, and scientific method, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams RA et al. (2015) Computational Psychiatry: Towards a mathematically informed understanding of mental illness. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry DOI: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun R (2001) Introduction to computational cognitive modeling In The Cambridge Handbook of Computational Psychology (1st edn) (Sun R, ed), pp. 3–20, Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinaugh D et al. (2019) Advancing the network theory of mental disorders: A computational model of panic disorder, PsyArXiv.

- 51.National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce Numerical weather prediction (weather models)..

- 52.Stensrud DJ (2007) Parameterization schemes: Keys to understanding numerical weather prediction models, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haslbeck JMB et al. (2019) Modeling psychopathology: From data models to formal theories, PsyArXiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Robinaugh D et al. (2020) Invisible hands and fine calipers: A call to use formal theory as a toolkit for theory construction, PsyArXiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Tinbergen N (1963) On aims and methods of ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 20, 410–433 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kagan J (2007) A trio of concerns. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2, 361–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Millner AJ et al. (2015) Single-item measurement of suicidal behaviors: Validity and consequences of misclassification. PLoS ONE 10, e0141606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hom MA et al. (2015) Limitations of a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history: Implications for standardized suicide risk assessment. Psychol. Assess. 28, 1026–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plöderl M et al. (2011) A closer look at self-reported suicide attempts: False positives and false negatives. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 41, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nock MK et al. (2018) Risk factors for the transition from suicide ideation to suicide attempt: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127, 139–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kleiman EM et al. (2017) Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 726–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nock MK et al. (2009) Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 816–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Millner AJ et al. (2017) Describing and Measuring the Pathway to Suicide Attempts: A Preliminary Study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 47, 353–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Molenaar PCM and Campbell CG (2009) The new person-specific paradigm in psychology. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18, 112–117 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barlow DH and Nock MK (2009) Why can’t we be more idiographic in our research? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamaker EL (2012) Why researchers should think within-person: A paradigmatic rationale In Handbook of research methods for studying daily life pp. 43–61, The Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smaldino P (2020) How to translate a verbal theory into a formal model, MetaArXiv.

- 68.Burger J et al. (2020) Bridging the gap between complexity science and clinical practice by formalizing idiographic theories: a computational model of functional analysis. BMC Med 18, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huys QJM et al. (2016) Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barak-Corren Y et al. (2017) Predicting suicidal behavior from longitudinal electronic health records. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 154–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walsh CG et al. (2017) Predicting risk of suicide attempts over time through machine learning. Clin. Psychol. Sci.

- 72.Kessler RC et al. (2015) Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 72, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kessler RC et al. (2017) Predicting suicides after outpatient mental health visits in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mol. Psychiatry 22, 544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephan KE and Mathys C (2014) Computational approaches to psychiatry. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 25, 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montague PR et al. (2012) Computational psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 72–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X-J and Krystal JH (2014) Computational psychiatry. Neuron 84, 638–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Corlett PR and Fletcher PC (2014) Computational psychiatry: a Rosetta Stone linking the brain to mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Friston KJ et al. (2014) Computational psychiatry: The brain as a phantastic organ. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bush RR and Mosteller F (1951) A mathematical model for simple learning. Psychol. Rev. 58, 313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guastello SJ and McGee DW (1987) Mathematical modeling of fatigue in physically demanding jobs. J. Math. Psychol. 31, 248–269 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bystritsky A et al. (2012) Computational non-linear dynamical psychiatry: A new methodological paradigm for diagnosis and course of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46, 428–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schiepek G et al. (2011) Nonlinear dynamics: Theoretical perspectives and application to suicidology. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 41, 661–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fartacek C et al. (2016) Real-time monitoring of non-linear suicidal dynamics: Methodology and a demonstrative case report. Front. Psychol. 7, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Bryan CJ et al. (2020) Nonlinear change processes and the emergence of suicidal behavior: A conceptual model based on the fluid vulnerability theory of suicide. New Ideas Psychol. 57, 100758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rogers ML and Joiner TE (2019) Exploring the temporal dynamics of the interpersonal theory of suicide constructs: A dynamic systems modeling approach. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 87, 56–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hawkley LC and Cacioppo JT (2010) Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 40, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.