Abstract

Mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) is the primary metabolite of the ubiquitous plasticizer and toxicant, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP). MEHP exposure has been linked to abnormal development, increased oxidative stress, and metabolic syndrome in vertebrates. Nuclear Factor, Erythroid 2 Like 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription factor that regulates gene expression in response to oxidative stress. We investigated the role of Nrf2a in larval steatosis following embryonic exposure to MEHP. Wild-type (WT) and nrf2a mutant (m) zebrafish embryos were exposed to 0 or 200 μg/L MEHP from 6 to either 96 (histology) or 120 hours post fertilization (hpf). At 120 hpf, exposures were ceased and fish were maintained in clean conditions until 15 days post fertilization (dpf). At 15 dpf, fish lengths and lipid content were examined, and the expression of genes involved in the antioxidant response and lipid processing was quantified. At 96 hpf, a subset of animals treated with MEHP had vacuolization in the liver. At 15 dpf, deficient Nrf2a signaling attenuated fish length by 7.7%. MEHP exposure increased hepatic steatosis and increased expression of PPARα target fabp1a1. Cumulatively, these data indicate that developmental exposure alone to MEHP may increase risk for hepatic steatosis, and that Nrf2a does not play a major role in this phenotype.

Keywords: Phthalate, MEHP, Nrf2, embryo, zebrafish, lipid accumulation, steatosis, DOHaD

INTRODUCTION

Phthalates are a family of chemicals utilized in the plastics production process to render plastic flexible [1]. Human phthalate exposure may occur through ingestion, inhalation, and or dermal contact, and can readily cross the placental barrier [2]. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) is among the most commonly used of the phthalates [3, 4]. Following exposure, DEHP is metabolized in the gastrointestinal tract into a variety of metabolites, including the bioactive metabolite mono-ethylhexyl phthalic acid (MEHP) [5]. MEHP has been identified as particularly toxic through both clinical and animal studies [6–10], shown to impact reproductive development such as disruption of male urogenital tract development [11]. Other research found significant associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and increased birth weight [12] as well as childhood and longitudinal Body Mass Index (BMI) [13]. Therefore, phthalates have been repeatedly characterized as ‘obesogens’, a term representing chemicals known to induce obesity, weight gain, and dyslipidemia (reviewed in [14–17]). On a molecular level, MEHP has been shown to cause damage both by inducing oxidative stress and by acting as an endocrine disruptor [18–21].

The cap’n’collar basic leucine zipper (CNC b-ZIP) transcription factor family plays a critical role in processes such as mitigating oxidative stress, cellular differentiation, carcinogenesis, and aging [22–24]. The CNC b-ZIP family includes Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2 (Nfe2), and three related factors: Nuclear Erthryoid-1 Related Factor (Nrf1), Nuclear Erthryoid-2 Related Factor (Nrf2) and Nuclear Erthryoid-3 Related Factor (Nrf3). In the presence of oxidative stress, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus whereby it heterodimerizes with small MAF proteins and binds to a cis-promoter element called the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) [25]. Binding to the ARE regulates a large family of cytoprotective genes [26]. In zebrafish, the nrf2a paralog is increasingly expressed during development [27], its expression is inducible by chemically stimulated oxidative stress [27], and is the primary inducer of cytoprotective gene expression [27–30]. Ultimately, inadequate Nrf2 antioxidant and cytoprotective function can result in the generation of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cytotoxic biochemical changes such as lipid peroxidation and DNA damage.

In mammalian models, the reduction of ROS has led to improvement of disease states and symptoms including diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and hyperlipidemia [31]. Additionally, in obese humans there is evidence of systemic oxidative stress, and reduction of oxidative stress has been shown to decrease the prevalence of metabolic syndrome [32]. The molecular mechanism of metabolic disorder phenotypes in response to oxidative stress is more unclear. The absence of Nrf2 was shown to decrease adiposity and adipocyte differentiation [19], potentially due to stimulation of glutathione metabolism [33], and yet another study has demonstrated no significant relationship [34]. Likewise, there are inconsistent results regarding the relationship between Nrf2 and obesity, and insulin resistance [35]. These inconsistencies could be the result of strategies investigating different tissues, cells lines, or animal models at varying windows of time throughout the lifecourse.

The liver plays a critical role in metabolic processes, and is a major site of Phase I and Phase II metabolism of toxicants [36]. In addition to xenobiotic metabolism, liver cells are central to a number of processes such as the production of bile, breakdown of fats, and enzymatic control of blood sugars via glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. These roles define the liver as a crucial metabolic regulator and indicate different pathways that may be impacted by liver damage. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses a spectrum of conditions ranging in severity. In its mildest form, NAFLD presents as simple steatosis (abnormal retention of lipid) in the liver [37]. Incurring further damage may lead to hepatitis (chronic liver inflammation), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and sometimes hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition to the implication of various metabolic processes, NAFLD is associated with both liver and cardiovascular related mortality [37]. Some studies have suggested that NAFLD rates are between 20 and 30 percent in the western world [38]. Although a high fat diet in conjunction with a sedentary life are generally pointed to as the key risk factors for NAFLD, toxicant exposure has also been shown to induce NAFLD [39].

A significant portion of the research investigating the role of Nrf transcription factors in metabolic disorder utilizes knockout models in conjunction with diet-induced obesity. Markedly less research has investigated the role of Nrf transcription factors in toxicant-induced metabolic disorder and obesity. Fewer studies yet have examined the embryonic period as a sensitive window of susceptibility during which exposures could induce pathological and physiological changes later in the lifecourse. Herein, we examine the role of the Nrf2a transcription factor in mediating lipid bioaccumulation, namely hepatic steatosis, in juvenile zebrafish that had been developmentally exposed to MEHP during the embryonic period.

METHODS

Chemicals

MEHP of the highest purity was purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA, USA). An MEHP stock solution of 2 mg/mL was prepared by dilution in the vehicle, DMSO. All solutions were stored in amber-tinted vials at −20°C and vortexed before use. All other chemicals used in this study were purchased directly from Fisher Scientific.

Animals

Homozygous Nrf2a wild-type and mutant (nrf2afh318−/−) fish crossed onto an AB strain background were obtained from Dr. Mark Hahn (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hold, MA). This strain of zebrafish was generated through the TILLING mutagenesis Project (R01 HD076585) and originally obtained by Dr. Hahn as embryos from the Moens Laboratory (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). The nrf2afh318−/− genotype is considered a loss-of-function mutation, since the point mutation produces a mutant amino acid sequence in the DNA binding domain of the Nrf2a protein, impairing its transcriptional activity. This mutation was originally characterized in [40], and further examined by our laboratory [9, 29, 41].

All animal use and care was conducted in strict accordance with protocols approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Bates College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (Animal Welfare Assurance Number UMASS A3551–01, Bates A3320–01). Adult breeding populations were housed in an Aquaneering automated zebrafish habitat at 28.5 °C and following a 14 h light:10 h dark cycle daily. Adult fish were fed the recommended amount of GEMMA Micro 300 (Skretting; Westbrook, ME) once daily in the morning. Breeding populations were housed at an appropriate density with a 2:1 female-to-male ratio. Embryos for experiments were collected within 1 hour post-fertilization (hpf) from homozygous genotyped tanks, washed thoroughly, and microscopically confirmed for fertilization prior to experimentation.

Exposures

Wild-type and mutant embryos were exposed to either DMSO (vehicle) or 200 μg/L MEHP through immersion beginning at 6 hpf (gastrula period, shield stage) and concluding at 120 hpf (fully developed larvae). This concentration of MEHP has been previously utilized and optimized in previous zebrafish studies, and we have previously shown that it impacts the expression of genes in the Nrf2 signaling pathway [9, 21]. MEHP or DMSO was added (0.01% v/v) to 0.3X Danieau’s medium (17 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 0.12mM MgSO4, 1.8mM Ca(NO3)2, 1.5mM HEPES, pH 7.6) for immersion. Media was 50% replaced every 24 hours and re-dosed with either DMSO or MEHP. Exposure took place in 20 ml glass scintillation vials with 5 embryos per vial. For each experiment, 3–5 vials were used per group. Three experimental replicates were performed to minimize clutch effects. At 96 hpf, some larvae were removed for analysis of yolk size and histology (n=30 per group). At 120 hpf, remaining larvae were individually placed in 150 ml beakers in a 1:1 mix of 0.3X Danieau’s medium to clean system (adult breeding facility) water. Fish were transitioned to 100% system water by refreshing 50% system water daily until 15 days post fertilization (dpf) on a 12h light:12h dark cycle at 28.5 °C and being fed Gemma Micro 75 (Skretting; Westbrook, ME, USA).

Microscopy

For larvae collected at 96 hpf, animals were anesthetized in 0.3X Danieau’s medium containing tricaine mesylate (MS-222) (a 2% solution prepared from 4 mg/ml tricaine powder in water, pH buffered and stored at −20°C until use) and staged in 3% methylcellulose. They were then imaged using a Leica M165 FC and the area of the yolk was quantified using LAS X software.

At 15 dpf fish were imaged for length using the methods described above. To capture images most useful for length analysis, fish were mounted on their side. Images of nrf2a mutant larvae were captured utilizing an upright Olympus compound microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam 503 camera and Zen analysis software (Zeiss, USA). All images were captured under 20× magnification. Following imaging, larvae were washed thoroughly in 0.3× Danieau’s medium and either preserved for lipid staining or used for RNA isolation.

Histology

At 96 hpf, DMSO (control)-treated and MEHP-treated WT animals were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in 1× phosphate buffer, dehydrated in ethanol and stored in 75% ethanol until embedding. Larvae were sent to Environmental Pathology Laboratories (Sterling, VA) where they were embedded laterally into paraffin. Sagittal sections were made serially every 2 μm. Sections were mounted on superfrost glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathology was conducted by a pathologist using an Olympus BX 40 with an Olympus DP25 camera system.

Lipid Staining via Oil Red O

To spatially quantify larval lipid content, 15 dpf larvae were stained with Oil Red O [42, 43]. Following length imaging, 3 pools of 5 larvae per treatment group were reserved for gene expression analysis and the remaining were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight. Larvae preserved in PFA were then washed three times in 1x phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) for a total of 6 minutes. Larvae were transferred to individual 2 ml glass vials, briefly bleached and then washed thoroughly with PBS (5 washes). Larvae were then washed with 80% propylene glycol for ten minutes, followed by 100% propylene glycol. Propylene glycol was removed, and larvae were stained with Oil Red O overnight. Fish were washed twice more with 80% and 100% propylene glycol following staining. Zebrafish were mounted on their side in 100% glycerol for imaging. Following imaging, stained larvae were stored indefinitely in glycerol.

RNA Isolation and Conversion to cDNA

Three pools of 5 larvae from each treatment group were used for RNA isolation. Following imaging at 15 dpf, RNA Later (Fisher Scientific) was added to 5 larvae per treatment group and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. Though individually housed from 5–15 dpf, larvae were randomized from the initial exposure vials to minimize batch effects. RNA was isolated using the GeneJET RNA purification Kit (Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The isolation protocol followed was developed for use of whole-tissue purification. The concentration of RNA and the purity of samples were analyzed using a μLITE spectrophotometer (BioDrop, Cambridge, UK), and all samples had quality A260/A280 ratios ranging from 1.8–2.1. After quantifying RNA, 500 ng RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). These samples were diluted to a concentration of 0.25 ng/μl of cDNA in nuclease-free water and stored at −20°C until use.

Gene Expression

Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted on the previously synthesized cDNA samples. Specifically, the Agilent M×3000 qPCR (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was used. Master Mix with Brilliant II SYBR Green was used in qPCR with the genes described above as well as on several housekeeping genes. Target genes were compared to the arithmetic mean of three housekeeping genes 18s, b2m, and beta actin utilizing the 2−ΔΔCT method [44, 45].

Triplicates of SYBR Master Mix and 10 ng of cDNA were performed for each sample. The conditions used in our qPCR were 95°C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30s, 55°C (65°C for beta actin) for 60s, and 72°C for 60 s. A melt curve was utilized to confirm the amplification of a singular product, and primers were tested for amplification of a single product prior to use using designed exon-spanning primers. Primer sequences and temperatures are listed in Supplemental Table 1. All primer pairs were optimized in house using standard curves (amplification efficiencies ranged from 90–100%) and temperature gradients (±1°C).

Data Analyses

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25). To select appropriate statistical tests, tests for skewness and Shapiro-Wilk tests for normality were performed. The relationships between fish length, genotype and exposure were analyzed using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Games-Howell post-hoc tests. To analyze the liver lipid content, red color intensity was normalized to image background using ImageJ (version 1.5, National Institutes of Health). These intensities were also compared across treatment and genotype using Kruskal-Wallis test with Games-Howell post-hoc tests. To analyze the relationship between genotype, treatment, and gene expression, qPCR data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons. A confidence level of 5% (α=0.05) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Embryonic Deformities

To first assess whether knockdown of Nfe2 and Nrf family transcription factors, in combination with MEHP exposure, can alter embryogenesis, we examined 96 hpf embryos exposed to MEHP after knockdown using morpholinos (Supplemental Figure 1). MEHP increased swim bladder abnormalities in control, nrf1a, and nrf2a morphants compared to DMSO controls. Heart rate was increased in nrf2b and nrf3 morphants exposed to MEHP. No other structural abnormalities were observed due to Nfe2 signaling or MEHP exposure (p>0.05). No changes were observed in yolk area between MEHP-exposed and control embryos (p>0.05).

Histology

At 96 hpf, wildtype animals were assessed at the tissue level, including the brain, neural cord, eyes, muscle, swim bladder, gut, pancreas, liver, gill, ear labyrinth, yolk sac, notochord and heart (sinus venous, atrium, ventricle and bulbus). Upon examination of three animals per group (DMSO control and MEHP treatment), the only noted difference was seen in the MEHP treated animals where the liver was highly vacuolated with large vacuoles as compared to DMSO control animals where no vacuoles were seen (Figure 1). Sections were scored to determine the presence of vacuolation and the type of vacuolation (fine, multifocal, or diffuse) (Supplemental Table 2). Sections were scored to determine the incidence of vacuolation in the liver, but also the degree of vacuolation within cells. Embryos exposed to MEHP has significantly greater scores for both vacuolation (p=0.001) and type of vacuolation (p=0.004) in the liver (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of histological sections through MEHP-exposed and DMSO-exposed (control) larval 96 hpf zebrafish. Images shown are 2 μm sections of paraffin-embedded larval tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A) Wild-type larvae treated with DMSO (control). Hepatocytes (arrow) show homogenous, non-vacuolated cytoplasm. B) Wild-type larvae treated with MEHP. Hepatocytes (indicated by an arrow) show large vacuoles expanding the cytoplasm.

Table 1.

MEHP exposure increases incidence and severity of vacuolation in the embryonic liver.

| DMSO | MEHP | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vacuolation | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 0.001 |

| type of vacuolation | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.004 |

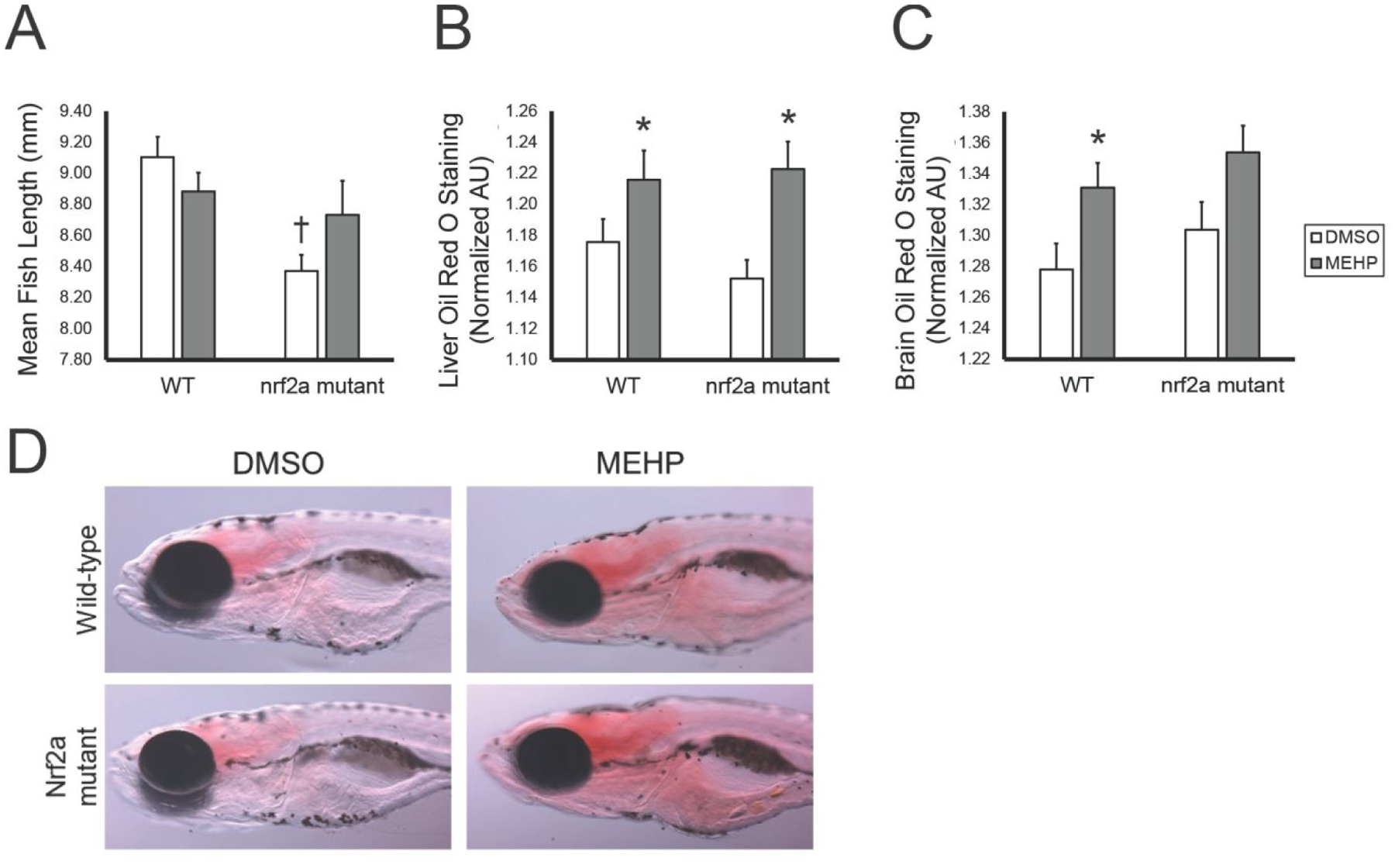

Fish length and Lipid Accumulation at 15 dpf

Following exposures from days 1–5, fish were then reared in clean conditions until day 15. Fish length measurements were taken at 15 dpf as a proxy for overall larval growth (Figure 2A). Overall, MEHP exposure did not significantly impact larval growth (p>0.05). In wild-type larvae, MEHP reduced fish length by 2.4%, though this decrease was not statistically significant (p>0.05). Compared to unexposed wild-type larvae, mutant larvae were shorter by 8% (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Fish growth and adiposity vary with MEHP-exposure and Nrf2a genotype at 15 dpf. Images were analyzed via ImageJ. Values are means ± standard error of the mean. (A) For fish length, ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc tests were used to assess exposure and genotyping changes in growth. Oil Red O staining intensity in the liver (B) and brain (C) was quantified, and assessed using Kruskal-Wallis tests with Games-Howell post-hoc tests. (D) Representative images of fish are shown, all at 50X magnification and the same light intensity. n=48–53 for all treatment groups. Asterisks (*) indicate a statistically significant change due to exposure, within each genotype. Daggers (†) indicate a statistically significant change due to genotype, within each exposure group. p<0.05.

Oil red O stain was utilized to spatially and quantitatively visualize neutral lipid accumulation in larvae at 15 dpf (Figures 2B and 2C). Developmental MEHP exposure significantly increased lipid content within the liver (p=0.002; Figure 2B). Though genotype did not statistically modify these relationships, the magnitude of change due to exposure in mutant larvae was greater. In the brain, staining was more intense in MEHP-exposed larvae compared to controls, though this trend was only statistically significant in wild-type larvae (p=0.016; Figure 2C).

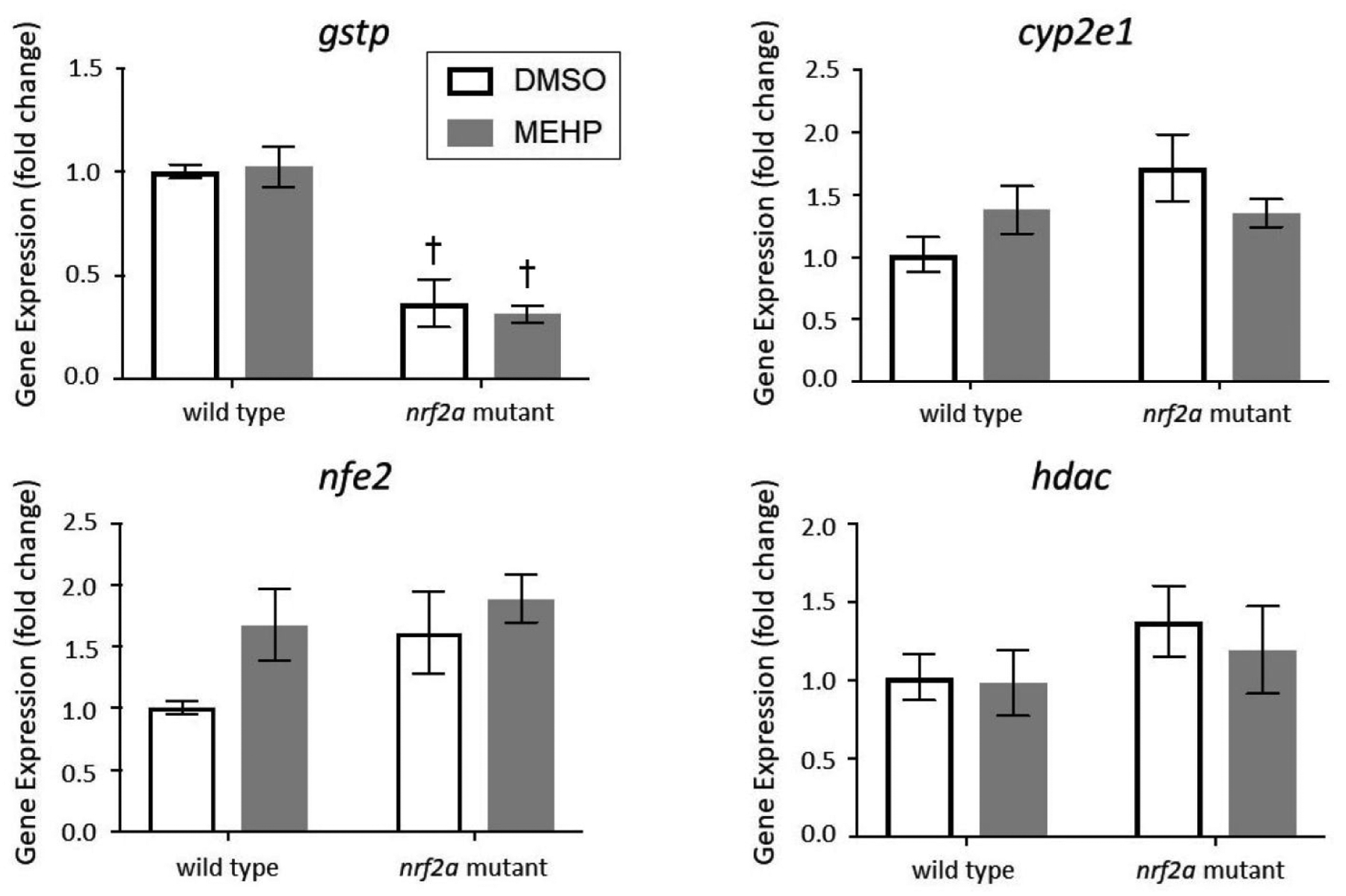

Gene Expression – Antioxidant Response and Nrf2 Interaction

Quantitative PCR was utilized to assess changes in gene expression resulting from MEHP exposures and impaired Nrf2a signaling (Figure 3). These genes were selected as targets of Nrf2 signaling or interaction with the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Glutathione-S-Transferase Pi (gstp) is a sensitive Nrf2-target, and a well-characterized indicator of Nrf2 induction. The transcription factor Nfe2 (nfe2), like Nrf2, is a member of the Cap’n’Collar (CNC) basic leucine zipper (b-ZIP) transcription factor family, and also mediates the antioxidant response in the embryo [46, 47]. Enzymes Cytochrome P450 2E1 (cyp2e1) and histone deacetylase (hdac) are involved in a myriad of cellular processes including chromatin structure and the hepatic xenobiotic response, and both enzymes have been shown to have interactions with Nrf2 signaling [48].

Figure 3.

Expression of gstp1, nfe2, cyp2e1 and hdac in wild-type and Nrf2a mutant zebrafish. Zebrafish embryos and larvae were exposed to DMSO or MEHP from 6 to 120 hpf, and gene expression was assessed at 15 dpf. Data are presented as mean fold change normalized to the mean of housekeeping genes 18s, b2m, and beta actin ± SEM. Data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons. Asterisks (*) indicate a statistically significant change due to exposure, within each genotype. Daggers (†) indicate a statistically significant change due to genotype, within each exposure group. p<0.05; n=3 pools of 5 larvae

Gene expression of gstp was significantly attenuated by approximately 60% in Nrf2a mutant larvae, regardless of exposure (p<0.05). No significant changes in gstp gene expression were observed due to MEHP exposure for either genotype (p>0.05). No statistically significant effects due to exposure or genotype were observed for nfe2 or cyp2e1 (p>0.05; Figure 3). There was also a subtle increase in nfe2 gene expression due to MEHP-exposure for both genotypes, and Nrf2a mutants had elevated expression compared to wild-type larvae (p>0.05). Expression of cyp2e1 and hdac was moderately increased in DMSO-exposed Nrf2a mutant larvae compared to wild-type larvae, but these trends were not statistically significant (p>0.05; Figure 3).

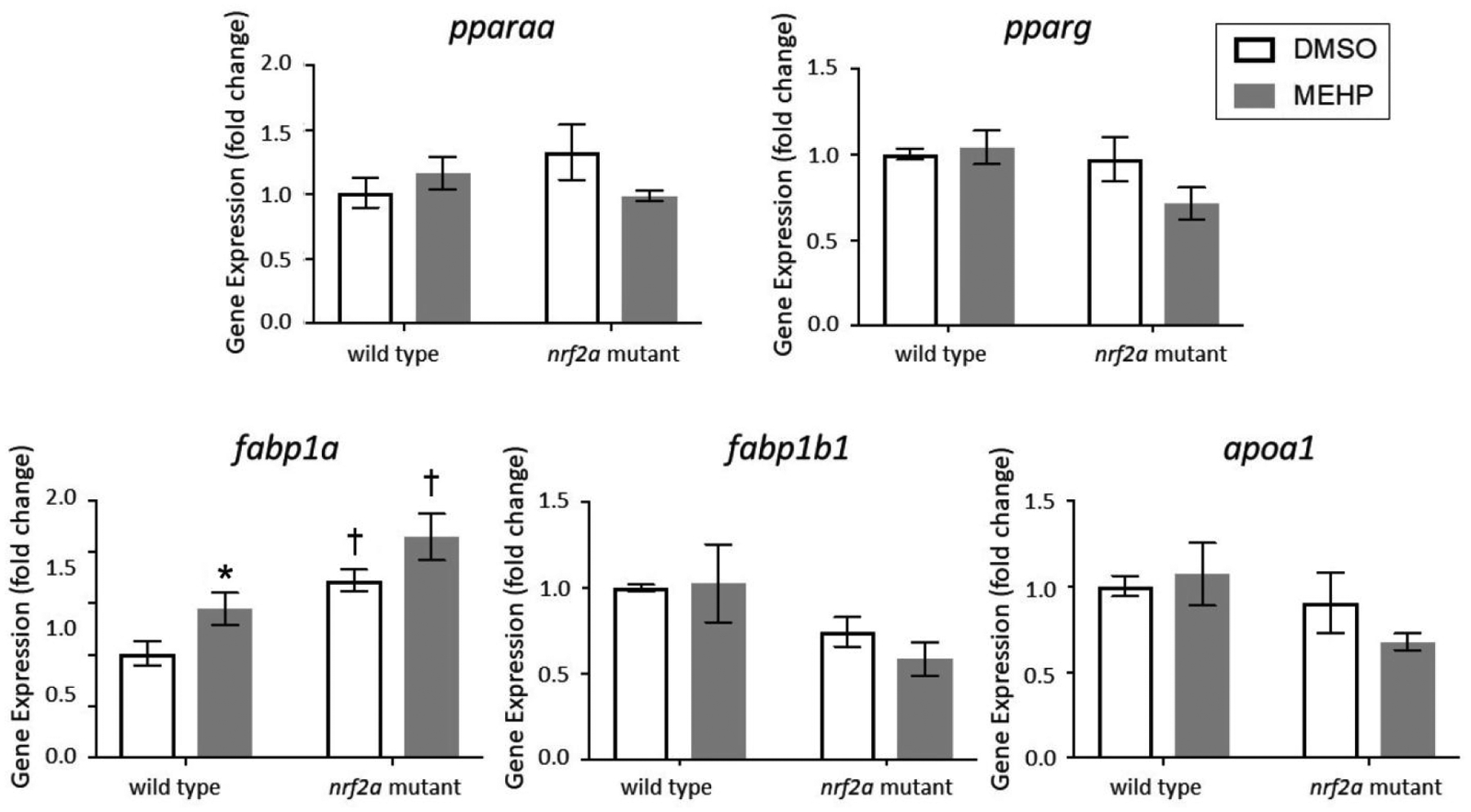

Gene Expression – PPAR Signaling

Gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (pparγ) and alpha (pparaa) and several of their targets were assessed at 15 dpf (Figure 4). PPARs are transcription factors with multifaceted regulatory domains over metabolic processes including, but not limited to, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, lipid metabolism and catabolism, and lipid transport. Expression of isoforms pparaa and pparg were measured as well as several of their gene targets, notably lipid transporter apolipoprotein A1 (apoa1a) and fatty acid binding proteins 1a and 1b (fabp1a, fabp1b.1). The gene apoa1a is a hepatic and yolk syncytial layer transporter involved in cholesterol and lipid transport, and is responsive to both PPARα and PPARγ signaling [49]. Fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) are intracellular carrier proteins responsible for lipid binding and transport in a myriad of tissues and systems [50]. Expression of fabp1a1 and fabp1b.1 is subfunctionalized in zebrafish, with fabp1a1 being responsive to PPARα signaling and fabp1b.1 being responsive to PPARγ signaling [51]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that MEHP is an activator of both PPARα and PPARγ signaling [52, 53]. However, it was unknown whether this activation would persist in larvae at 15 dpf after only developmental exposures ceasing at 5 dpf.

Figure 4.

Expression of pparaα, pparg, fabp1a1, fabp1b1, and apoa1a in wild type and nrf2a mutant zebrafish. Zebrafish embryos and larvae were exposed to DMSO or MEHP from 6 to 120 hpf, and gene expression was assessed at 15 dpf. Data are presented as mean fold change normalized to the mean of housekeeping genes 18s, b2m, and beta actin ± SEM. Data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons. Asterisks (*) indicate a statistically significant change due to exposure, within each genotype. Daggers (†) indicate a statistically significant change due to genotype, within each exposure group. p<0.05; n=3 pools of 5 larvae

No statistically significant changes in gene expression were observed for either the pparaa or pparg transcription factors, nor for targets apoa1a or fabp1b.1 (p>0.05; Figure 4). However, there were notable decreasing trends in apoa1a and fabp1b.1 in Nrf2a mutants and Nrf2a mutants embryonically exposed to MEHP (p>0.05). Expression of fabp1a1 was increased by MEHP exposure in wild-type larvae, and Nrf2a mutants were elevated compared to wild-type larvae regardless of exposure (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential interaction between developmental exposure to MEHP and the antioxidant response and their impact on larval steatosis. We hypothesized that embryonic MEHP exposure would increase larval lipid accumulation, and that impaired Nrf2a function would exacerbate this phenotype. Our data indicate that developmental MEHP exposure increases risk for hepatic steatosis in larval zebrafish. Significant decreases in gstp gene expression are concordant with previously reported understandings of the role of Nrf2a in cytoprotection, and increased fabp1a1 in mutants and due to MEHP exposures suggests a PPARα-mediated adaptive response to steatosis. The exacerbation of steatosis as well as increased fabp1a1 expression in Nrf2a mutant larvae due to MEHP exposures suggests that Nrf2a may function in hepatoprotection.

In this study, developmental MEHP exposure reduced mean fish length by 2.2% in wild-type larvae, though this decrease was not statistically significant (p>0.05). However, unexposed Nrf2a mutant larvae were 7.7% shorter than wild-type larvae (Figure 2), suggesting that Nrf2a may play a role in overall growth and development. Most significantly, these phenotypic effects were observed at 15 dpf—after being only exposed from 6–120 hpf. We have previously observed this decrease in total fish length due to other developmental toxicant exposures (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid; [54]), but not in Nrf2a mutant fish examined at earlier timepoints (7 dpf; [29]). Only a modest 4–6% decrease in human fetal length exists between the median infant length and fetuses small for gestational age (SGA), which is defined as the lowest 10th percentile for fetal growth according to the Fenton growth chart [55]. Therefore, the 7.7% reduction in fish length observed in this study are physiologically relevant and may propagate other phenotypic and metabolic changes commonly associated with SGA or low birth weight classifications (reviewed in [56–58]).

The prevalence of pediatric obesity and overweight children has been steadily increasing in recent decades [59, 60]. Here, we assessed how a ubiquitous environmental toxicant, MEHP, impacts developmental steatosis and examined the modification of this relationship by the antioxidant response pathway. We confirmed the results of previous studies, demonstrating that MEHP exposures increased hepatic steatosis, even as early as 120 hpf (Figure 1). Hepatic steatosis at 15 dpf was significantly increased by developmental MEHP exposure in both wild-type and Nrf2a mutant larvae (Figure 2). These data indicate that early developmental exposures alone to MEHP may increase risk for juvenile hepatic steatosis, even if exposures are remediated during the larval period. Several studies have previously shown that exposures to MEHP or parent compound DEHP increased lipid accumulation in vitro or hepatic steatosis in vivo [61–63]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that exposures during the embryonic period alone are capable of inducing lasting steatosis into the larval period.

We have previously shown that embryonic exposures to MEHP impacted the expression of Nrf2a targets gsr and gstp1 in 96 hpf zebrafish, but that the embryonic glutathione redox couple was not significantly impacted [9]. We also previously demonstrated that the oxidative response to MEHP is rapid, occurring primarily within the first few hours after exposure, in mouse whole embryo culture [10]. Therefore, the timing of glutathione and antioxidant enzyme assessment relative to exposure is an important variable in MEHP-induced oxidative stress research. In this study, we examined the gene expression of antioxidant enzymes at 15 dpf following developmental exposures (from 6–120 hpf). This delayed assessment of the antioxidant response allowed us to probe the more programmatic or longitudinal impacts of developmental exposures rather than an acute response. Here, we found that gstp1 expression was decreased by impaired Nrf2a signaling but that MEHP had no impact on gstp1 expression (Figure 3). Therefore, it is unlikely that developmental exposures to MEHP induce acute oxidative effects, but that this acute oxidative stress does not produce any direct chronic oxidative effects.

The endogenous antioxidant response is coordinated largely by the Nfe2 family of transcription factors, including Nrf1a, Nrf1b, Nrf2a, Nrf2b, Nrf3, and Nfe2 in the zebrafish model. We have previously published several studies examining the oxidative stress response and embryonic phenotypes of deficient signaling by this antioxidant family, and have observed that several of these family members have redundant functions and may compensate for another’s impairment [27, 30, 47]. Here, we observed decreased gstp1 gene expression in Nrf2a mutant larvae and stable gene expression of family member nfe2 regardless of genotype or exposure (Figure 3). Therefore, it is unlikely that compensation of deficient Nrf2a signaling is occurring, at least not via the Nfe family of antioxidant transcription factors.

PPAR activity has been widely implicated in environmental determinants of metabolic dysfunction due to its regulatory role in processes such as carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and storage. In zebrafish, PPARs are expressed in a myriad of tissues throughout the entire lifecourse, suggesting constitutive gene expression [64]. However, the differential expression of PPAR genes in various tissues and in response to metabolic conditions also demonstrates the potential for induction of this signaling pathway. PPARα agonism has been widely explored and developed as potential therapeutic for hepatic steatosis, and increased expression has as an adaptive response to ameliorate hepatic steatosis (reviewed in [65]). We had previously found that developmental exposures to another environmental toxicant, PFOS, could induce PPAR gene expression in developing embryos, but had not assessed any more longitudinal changes in expression after 96 hpf [29]. In this study, gene expression of pparg and pparaa was not changed at 15 dpf despite increased hepatic steatosis resulting from both developmental MEHP exposure and deficient Nrf2a signaling (Figure 4). However, expression of PPARα-target fabp1a1 was increased by both MEHP exposure and impaired Nrf2a signaling—suggesting that PPARα activity, rather than expression, may be modulated by exposure and genotype. Therefore, future work should complement these measures with protein expression, cellular localization, and transcriptional regulation (such as by Chromatin ImmunoPrecipitation and sequencing, or ChIP-seq) data to probe the activity and induction of PPARα.

The potential for crosstalk between the Nrf2 and PPAR signaling pathways needs to be explored. We previously identified putative AREs within the promoter of pparaa and pparg in zebrafish, as well as PPAR-response elements (PPREs) in the promoters of Nfe2 family members and their targets [29]. Likewise, we had found that the expression of pparaa and pparg to exposure was only induced in nrf2a mutant embryos [29]. In the present study, we observed no statistically significant changes in gene expression of pparaa or pparg in Nrf2a mutant larvae (Figure 4). These data suggest that any potential Nrf2-PPAR crosstalk is unlikely to play a significant role in MEHP-induced steatosis.

A limitation of this study is the inability to observe sex-based differences in hepatic steatosis in larval zebrafish. Unlike mammalian models, zebrafish sexual differentiation is polygenic, meaning that it is not simply determined by a singular genetic locus [66]. Due to this complexity, sexual determination does not occur in zebrafish until approximately 30 dpf, marking the change from the larval to the juvenile period [67]. Studies utilizing rodents to investigate metabolic outcomes of phthalate exposure in juveniles found sexually dimorphic responses in numerous phenotypes, expected due to the endocrine disrupting properties of phthalates. There is ample epidemiologic and model data demonstrating that males are at a higher risk for obesity, diabetes, and NAFLD than women, and that these relationships are modified by age [68–70]. Therefore, future longitudinal studies beyond the larval stage need to explore the role of biological sex in MEHP-induced hepatic steatosis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that early developmental exposures to MEHP increased hepatic steatosis during the mid-larval period more than 10 days after exposure. These data suggest that there are lasting metabolic effects from embryonic exposures and provide further evidence that MEHP may contribute to the developmental origins of metabolic dysfunction. Nrf2a antioxidant signaling did not play a significant role in MEHP-induced steatosis, though decreased Nrf2a signaling increased fabp1a gene expression regardless of exposure. Overall, this study demonstrates the significance of embryonic-only exposures in the developmental origins of metabolic dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103423 to Bates College) as well as support from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES025748 and R01 ES028201 to ART-L; F32 ES028085 to KES). This work was possible due to the exceptional animal care and laboratory assistance of Christopher Clark, Sarah Conlin, Mary Hughes, Sadia Islam, Archit Rastogi, Monika Roy, Olivia Venezia, and Michael Young.

References

- 1.Phthalates Action Plan, U.S.E.P Agency, Editor. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin S, et al. , Phthalates impact human health: Epidemiological evidences and plausible mechanism of action. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017. 340: p. 360–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittassek M and Angerer J, Phthalates: metabolism and exposure. Int J Androl, 2008. 31(2): p. 131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latini G, De Felice C, and Verrotti A, Plasticizers, infant nutrition and reproductive health. Reproductive Toxicology, 2004. 19(1): p. 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, and Andersson AM, Metabolism of phthalates in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res, 2007. 51(7): p. 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inada H, et al. , Evaluation of ovarian toxicity of mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) using cultured rat ovarian follicles. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences, 2012. 37(3): p. 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomita I, et al. , Fetotoxic effects of mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) in mice. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1986. 65: p. 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guibert E, et al. , Effects of mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) on chicken germ cells cultured in vitro. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2013. 20(5): p. 2771–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs HM, et al. , Embryonic exposure to Mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) disrupts pancreatic organogenesis in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere, 2018. 195: p. 498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sant KE, et al. , Mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate disrupts neurulation and modifies the embryonic redox environment and gene expression. Reproductive Toxicology, 2016. 63: p. 32–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swan SH, et al. , First trimester phthalate exposure and anogenital distance in newborns. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 2015. 30(4): p. 963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sathyanarayana S, et al. , First Trimester Phthalate Exposure and Infant Birth Weight in the Infant Development and Environment Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2016. 13(10): p. 945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harley KG, et al. , Association of prenatal urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and childhood BMI and obesity. Pediatric research, 2017. 82(3): p. 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heindel JJ, History of the Obesogen Field: Looking Back to Look Forward. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2019. 10: p. 14–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heindel JJ and Blumberg B, Environmental Obesogens: Mechanisms and Controversies. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 2019. 59: p. 89–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grün F and Blumberg B, Endocrine disrupters as obesogens. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2009. 304(1): p. 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grün F and Blumberg B, Environmental Obesogens: Organotins and Endocrine Disruption via Nuclear Receptor Signaling. Endocrinology, 2006. 147(6): p. s50–s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, et al. , Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces oxidative stress and inhibits growth of mouse ovarian antral follicles. Biology of reproduction, 2012. 87(6): p. 152–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pi J, et al. , Deficiency in the Nuclear Factor E2-related Factor-2 Transcription Factor Results in Impaired Adipogenesis and Protects against Diet-induced Obesity. 2010. 285(12): p. 9292–9300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheikh IA, et al. , Endocrine disruption: In silico perspectives of interactions of di-(2ethylhexyl)phthalate and its five major metabolites with progesterone receptor. BMC structural biology, 2016. 16(Suppl 1): p. 16–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhai W, et al. , Thyroid Endocrine Disruption in Zebrafish Larvae after Exposure to Mono-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (MEHP). PLOS ONE, 2014. 9(3): p. e92465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelton P and Jaiswal AK, The transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2): a protooncogene? FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2013. 27(2): p. 414–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong M, Kan YW, and Chan JY, The CNC basic leucine zipper factor, Nrf1, is essential for cell survival in response to oxidative stress-inducing agents. Role for Nrf1 in gamma-gcs(l) and gss expression in mouse fibroblasts. Vol. 274 2000. 37491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sykiotis GP and Bohmann D, Stress-activated cap’n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Science signaling, 2010. 3(112): p. re3–re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Q, Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2013. 53: p. 401–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Espinosa-Diez C, et al. , Antioxidant responses and cellular adjustments to oxidative stress. Redox Biology, 2015. 6: p. 183–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timme-Laragy AR, et al. , Nrf2b, novel zebrafish paralog of oxidant-responsive transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2). J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(7): p. 4609–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi M, et al. , Identification of the interactive interface and phylogenic conservation of the Nrf2-Keap1 system. Genes Cells, 2002. 7(8): p. 807–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sant KE, et al. , Nrf2a modulates the embryonic antioxidant response to perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Aquat Toxicol, 2018. 198: p. 92–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sant KE, et al. , The role of Nrf1 and Nrf2 in the regulation of glutathione and redox dynamics in the developing zebrafish embryo. Redox Biol, 2017. 13(Supplement C): p. 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furukawa S, et al. , Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2004. 114(12): p. 1752–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marseglia L, et al. , Oxidative stress in obesity: a critical component in human diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2014. 16(1): p. 378–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi T, et al. , Carnosic acid and carnosol inhibit adipocyte differentiation in mouse 3T3-L1 cells through induction of phase2 enzymes and activation of glutathione metabolism. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2009. 382(3): p. 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin S, et al. , Role of Nrf2 in prevention of high-fat diet-induced obesity by synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-Imidazolide. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2009. 620(1): p. 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo H-A and Lee I-K, The role of Nrf2: adipocyte differentiation, obesity, and insulin resistance. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2013 2013: p. 184598–184598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Physiology, Liver. 2018. 18 December 2018 [cited 2019 4/3/19]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535438/.

- 37.Benedict M and Zhang X, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An expanded review. World journal of hepatology, 2017. 9(16): p. 715–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sayiner M, et al. , Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the United States and the Rest of the World. Clinics in Liver Disease, 2016. 20(2): p. 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arciello M, et al. , Environmental Pollution: A Tangible Risk for NAFLD Pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2013. 14(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukaigasa K, et al. , Genetic evidence of an evolutionarily conserved role for Nrf2 in the protection against oxidative stress. Molecular and cellular biology, 2012. 32(21): p. 4455–4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rousseau ME, et al. , Regulation of Ahr signaling by Nrf2 during development: Effects of Nrf2a deficiency on PCB126 embryotoxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2015. 167: p. 157–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlegel A and Stainier DYR, Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein Is Required for Yolk Lipid Utilization and Absorption of Dietary Lipids in Zebrafish Larvae. Biochemistry, 2006. 45(51): p. 15179–15187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraher D, et al. , Lipid Abundance in Zebrafish Embryos Is Regulated by Complementary Actions of the Endocannabinoid System and Retinoic Acid Pathway. Endocrinology, 2015. 156(10): p. 3596–3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD, Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT Method. Methods, 2001. 25(4): p. 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCurley AT and Callard GVJBMB, Characterization of housekeeping genes in zebrafish: male-female differences and effects of tissue type, developmental stage and chemical treatment. 2008. 9(1): p. 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams LM, et al. , The transcription factor, Nuclear factor, erythroid 2 (Nfe2), is a regulator of the oxidative stress response during Danio rerio development. Aquatic toxicology (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2016. 180: p. 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams LM, et al. , Developmental Expression of the Nfe2-Related Factor (Nrf) Transcription Factor Family in the Zebrafish, Danio rerio. PLOS ONE, 2013. 8(10): p. e79574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cederbaum AI, Nrf2 and Antioxidant Defense Against CYP2E1 Toxicity, in Cytochrome P450 2E1: Its Role in Disease and Drug Metabolism, Dey A, Editor. 2013, Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht: p. 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thisse B, et al. , Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis (NIH R01 RR15402), in ZFIN Direct Data Submission (http://zfin.org). 2001.

- 50.Fagerberg L, et al. , Analysis of the Human Tissue-specific Expression by Genome-wide Integration of Transcriptomics and Antibody-based Proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 2014. 13(2): p. 397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laprairie RB, Denovan-Wright EM, and Wright JM, Subfunctionalization of peroxisome proliferator response elements accounts for retention of duplicated fabp1 genes in zebrafish. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 2016. 16(1): p. 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feige JN, et al. , The Endocrine Disruptor Monoethyl-hexyl-phthalate Is a Selective Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ Modulator That Promotes Adipogenesis. 2007. 282(26): p. 19152–19166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hurst CH and Waxman DJ, Activation of PPARα and PPARγ by Environmental Phthalate Monoesters. Toxicological Sciences, 2003. 74(2): p. 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sant KE, et al. , Embryonic exposures to perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) disrupt pancreatic organogenesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Environmental Pollution, 2017. 220: p. 807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fenton TR and Kim JH, A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatrics, 2013. 13(1): p. 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dulloo AG, et al. , The thrifty ‘catch-up fat’ phenotype: its impact on insulin sensitivity during growth trajectories to obesity and metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Obesity, 2006. 30(4): p. S23–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaag A, Low birth weight and early weight gain in the metabolic syndrome: Consequences for infant nutrition. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 2009. 104(Supplement): p. S32–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simmons R, Developmental origins of adult metabolic disease: concepts and controversies. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2005. 16(8): p. 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan L, et al. , Trends in Severe Obesity Among Children Aged 2 to 4 Years Enrolled in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children From 2000 to 2014Trends in Severe Obesity Among US Children Aged 2 to 4 Years Enrolled in WICTrends in Severe Obesity Among US Children Aged 2 to 4 Years Enrolled in WIC. JAMA Pediatrics, 2018. 172(3): p. 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, and Ogden CL, Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Children and Adolescents: United States, 1963–1965 Through 2011–2012, N.C.f.H. Statistics, Editor. 2014, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bai J, et al. , Mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate induces the expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis in HepG2 cells. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2019. 69: p. 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Y, et al. , Mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) promoted lipid accumulation via JAK2/STAT5 and aggravated oxidative stress in BRL-3A cells. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019. 184: p. 109611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira C, Mapuskar K, and Rao CV, Chronic toxicity of diethyl phthalate in male Wistar rats—A dose–response study. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2006. 45(2): p. 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibabe A, Bilbao E, and Cajaraville MP, Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in zebrafish (Danio rerio) depending on gender and developmental stage. Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 2005. 123(1): p. 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liss KHH and Finck BN, PPARs and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochimie, 2017. 136: p. 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liew WC, et al. , Polygenic sex determination system in zebrafish. PLOS ONE, 2012. 7(4): p. e34397–e34397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uchida D, et al. , Oocyte apoptosis during the transition from ovary-like tissue to testes during sex differentiation of juvenile zebrafish. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2002. 205(6): p. 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips ML, Phthalates and Metabolism: Exposure Correlates with Obesity and Diabetes in Men. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007. 115(6): p. A312–A312. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ballestri S, et al. , NAFLD as a Sexual Dimorphic Disease: Role of Gender and Reproductive Status in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Inherent Cardiovascular Risk. Advances in Therapy, 2017. 34(6): p. 1291–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bertolotti M, et al. , Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and aging: epidemiology to management. World journal of gastroenterology, 2014. 20(39): p. 14185–14204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cooper CA, Handy RD, and Bury NR, The effects of dietary iron concentration on gastrointestinal and branchial assimilation of both iron and cadmium in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic Toxicology, 2006. 79(2): p. 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao X, et al. , Klf6/copeb is required for hepatic outgrowth in zebrafish and for hepatocyte specification in mouse ES cells. Developmental Biology, 2010. 344(1): p. 79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Timme-Laragy AR, et al. , Nrf2b, novel zebrafish paralog of oxidant-responsive transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2). The Journal of biological chemistry, 2012. 287(7): p. 4609–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schultz LE, et al. , Epigenetic regulators Rbbp4 and Hdac1 are overexpressed in a zebrafish model of RB1 embryonal brain tumor, and are required for neural progenitor survival and proliferation. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 2018. 11(6): p. dmm034124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.