Abstract

Gas plasmas, created in atmospheric pressure conditions, both thermal (hot) and non-thermal (cold) are emerging as useful tools in medicine. During surgery, hot gas plasmas are useful to reduce thermal damage and seal blood vessels. Gas plasma pens use cold gas plasma to produce reactive chemical species with selective action against cancers, which can be readily exposed in surgery or treated from outside of the body. Solutions activated by cold gas plasma have potential as a novel treatment modality for treatment of less readily accessible tumours, or those with high metastatic potential. This review summarises the preclinical and clinical trial evidence currently available, as well as the challenges for translation of direct gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solution treatment into regular practice.

Keywords: Plasma, Atmospheric pressure gas plasma, Gas plasma, Gas plasma activated solution, Cancer treatment, RONS

Introduction

Gas plasmas, or ionised gases, have many developing applications in medicine, particularly in areas of wound healing, disinfection, cancer treatment as well as in dentistry (Laroussi 2020). A search of PubMed and Web of Science, under the terms cold, atmospheric, plasma and medicine reveals from the growth in the number of publications (Fig. 1) that gas plasma medicine is a relatively new and rapidly developing field. The research is evolving and translation into clinical practice has begun, with specific applications in surgical instruments, as well as in instruments for the treatment of chronic and infected wounds (Metelmann et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

Growth in the number of publications found through PubMed and Web of Science containing variations of the search terms cold, atmospheric, gas plasma and medicine

Gas plasma, ionised gas or vapour, is known as the fourth state of matter and is common throughout the universe, in stars and luminous clouds. Gas plasma has been known since ancient times in the forms of lightning, where electrons and positive ions are heated suddenly to high temperatures and in the quiescent discharge known as St Elmo’s fire or corona discharge, in which strong electric fields near sharp points cause ionisation of the air. Gas plasma is present whenever there is an electrical discharge in a gas. Applications in welding, lighting and surface coating have been widely developed for industrial use, whilst the applications in medicine are growing quickly.

In the medical community, gas plasma is still a novelty and is frequently and mistakenly confused with blood plasma. Gas plasma applications in cancer treatment have been both direct, where the gas plasma is directed onto tissue and indirect, where reactive chemical species similar to those generated by radiation beams are generated in a solution, which is then used for treatment. Direct use of gas plasma in instruments for surgical excision has found commercial application, enabling the transition of gas plasma from bench to bedside. Interestingly, for cancer treatment, direct exposure of the tumour (Metelmann et al. 2018) or the bed of the tumour to gas plasma has shown therapeutic advantage and is currently under clinical trial (number NCT04267575).

The field of gas plasma–activated solution therapy is at an early stage, with limited available preclinical data; however, some patterns of response are already becoming clear. Exposure to gas plasma–activated solutions appears to selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells at concentrations that do little harm to healthy cells. Proliferation and adhesion are reduced in vitro and it has been hypothesised that gas plasma treatment reduces the metastatic potential of certain cancers (Freund et al. 2019). Gas plasma–activated solution as an indirect form of gas plasma treatment is a clinically compatible treatment modality, because the solution can be both stored at room temperature and frozen, whilst still retaining its anticancer properties (Tanaka et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2016; Mohades et al. 2016; Tanaka et al. 2011).

Despite the advances in the treatment of cancer with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, some patients are still failed by their treatment, succumbing to their disease. More recently, traditionally poor prognosis cancers have seen improvements with emerging treatments such as immunotherapy and sophisticated targeting of ionising radiation. These poor prognosis cancers include ovarian, lung, brain and pancreatic, for which the overall 5-year survival rate is 4% (Freelove and Walling 2006) and for ovarian cancer is 30% (Alrehaili et al. 2020). Glioblastoma has a median post-diagnosis survival time of 16 months and there is no known cure (Almeida et al. 2019). Consequently, the need to find a new angle or a different mechanism by which to control cancer, particularly for the patients where treatments currently fail, cannot be understated. Gas plasma medicine is emerging as a modality that offers an opportunity for improved outcomes.

In this review, we will describe the progress in and challenges for the clinical implementation of gas plasma medicine, with a special focus on cancer treatment. Our aim is to summarise the science for the non-specialist and to review the preclinical evidence currently available for the use of gas plasma in treatments for cancer and to highlight knowledge gaps that present challenges for translation into the clinic. To support the clinical translation of gas plasma, the next step is an improved understanding of the mechanisms of action in order to understand how to control and optimise dose prescription and delivery of the active agents for a predetermined clinical outcome.

What is gas plasma and what is gas plasma–activated solution?

Gas plasma consists of negatively charged free electrons and positive ions. The numbers of ions and electrons are generally equal except in small volumes near surfaces, where electric fields are strong. Gas plasma is conveniently created when electrical current is carried in gas or vapour as a discharge between two electrodes. The positive ions in the discharge are usually at a temperature that is raised to varying extents above ordinary temperatures. If the ions are only slightly above room temperature, at approximately 40 °C, the gas plasma is ‘cold’ and if it is substantially above, reaching hundreds of degrees depending on the current carried, it can be ‘hot’. Sometimes the electrodes are heated by the passage of current or by contact with the gas plasma and can be very hot, even molten or vaporised and can then contribute ions to the discharge. The current can be steady, pulsed or oscillating and if pulsed or oscillating, the frequency can cover a wide range from audio through to radio and microwave frequencies.

Gas plasma–activated solution is a liquid medium that has been exposed to gas plasma, typically a cold gas plasma and retains some reactive species created as a result of interaction with ions and electrons. Important properties of all gas plasmas relevant to the creation of reactive species are the electron density and the electron energy distribution, determined by the electron temperature where that can be defined. The gas plasma can also contain reactive atomic and molecular species, including unstable or metastable excited atoms or ions, radical groups and other reactive groups containing oxygen, nitrogen and carbon, depending on the gas which is used to create the gas plasma. Cell culture medium, Ringer’s lactate solution, saline solution and water are the most commonly used liquids for generating gas plasma–activated solutions. Typically, a dielectric barrier discharge, an atmospheric pressure gas plasma jet or a ‘gas plasma pen’ are common gas plasma sources for treating liquid solutions (see Fig. 2). The dielectric barrier discharge setup typically uses two electrodes, at least one of which is covered by an insulating or dielectric material, such as polymer, glass or quartz. The dielectric material, being poorly conductive, prevents direct charge exchange with the gas plasma, generally limiting the energy that flows into the gas and keeping the gas plasma in a cool or non-thermal state (Brandenburg 2017). This non-thermal state, where the temperature of the gas is much lower than the temperature of the electrons, is very important for the gas plasma’s ability to activate the solution without adding excessive heat which may result in evaporation or damage to living tissue. Atmospheric pressure gas plasma jets and gas plasma pens are dielectric barrier discharge devices that consist of a dielectric tube with two ring electrodes (Fig. 2(a)), or one ring electrode and one needle-like high voltage electrode located on the axis of the tube (Fig. 2(b)). The gas flows through the tube, becomes ionised by the capacitive coupling of energy from the electrodes and continues to flow out of the end of the tube as a plume of cold gas plasma. This plume can be used to directly treat live tissue, or applied above or directly upon the surface of a solution. One advantage of the dielectric barrier discharge system is that it can be orientated to provide a directed plume of gas plasma. For example, gas plasma pens are much smaller hand-held devices which can produce a precise gas plasma plume that delivers reactive species for the treatment of localised areas such as a skin lesion or individual wells in a well plate containing cell culture medium.

Fig. 2.

Three types of devices for gas plasma medicine operating at atmospheric pressure. (a) and (b) show a gas plasma pen where a cold, low current dielectric barrier discharge is excited by a pulsed or oscillating voltage applied to (a) two electrodes surrounding a dielectric tube carrying gas and (b) one electrode outside the dielectric tube and the other electrode inside and coaxial with the tube. For both (a) and (b), a plume carrying reactive species to the treatment region is formed in the flowing gas. The treatment region may or may not be part of the circuit. (c) shows a surgical tool for treating tissue using a hot gas plasma at higher current. The treatment region forms part of the circuit, where heat is delivered by the gas plasma discharge and by direct ohmic heating from the current carried in the gas plasma

A who’s who of reactive species

During the creation of gas plasma, a range of reactive chemical species are generated. As a non-exclusive list, these include hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, nitric oxide, nitrate and nitrite ions, singlet oxygen, superoxide and ozone. Many of these chemical species are produced by radiation beams in the patient during radiotherapy (Ji et al. 2019). It is generally accepted that reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) are responsible for the effectiveness of gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solutions in the treatment of cancer (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a; Kaushik et al. 2018; Graves 2012). It is hypothesised that some of the observed beneficial effects are caused by synergistic interactions between the reactive species, which are generated by gas plasma acting on a solution (Girard et al. 2016; Kurake et al. 2016). For an in-depth exploration of the physics of reactive species generation in gas plasma, the reader is referred to the extensive review provided by Lu et al. (2016), and for more information on the chemistry of reactive species, the reader is referred to Kaushik et al. (2018).

Detecting the presence and measuring the concentration of reactive species are not easy tasks; the short life span of some of these species, unknown intermediates and the sheer multitude of agents already present in some treated solutions, such as cell culture medium, make it difficult to fully characterise the reactive species in solution (Gorbanev et al. 2018). The parameters of the process used to create the activated solution affect the concentration of reactive species and thus their biological effects. The composition and volume of the solution treated, dilution ratio, gas plasma composition, properties and application time, distance between the gas plasma plume and the solution surface all contribute to the type and concentration of reactive species generated (Takeda et al. 2017). A key distinction between the direct treatment with gas plasma and treatment with gas plasma–activated solutions is the complement of reactive species, due to the various species lifetimes. Direct gas plasma treatment enables the use of very short-lived species, whilst gas plasma–activated solutions contain a complement of longer-lived species, depending on its storage time. The lifetimes of the various species in solution have been simulated (Hamaguchi 2013), but when determined experimentally, they are heavily dependent on the type of solution being treated and the pH. The physiological conditions found in in vivo treatment situations will affect the lifetimes (Szili et al. 2018). Figure 3 shows the distribution of predicted concentrations of reactive species in pure water, as a function of gas plasma treatment time, and Table 1 provides more information on their lifetimes after gas plasma exposure has ended.

Fig. 3.

The simulated density of reactive species as a function of time of exposure of pure water to gas plasma, assuming OH and NO radicals are produced in the gas plasma. The assumed dissolving rates are OH: 1.0 × 10−1 mol L−1 s−1 and NO: 7.6 × 10−4 mol L−1 s−1. Reproduced with permission from Hamaguchi (2013) and AIP Publishing

Table 1.

Range of reactive species generated in a gas plasma plume, and their properties relevant to cellular mechanisms

| Name | Features and Generation | Half lives | Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide radical (O2−) | Negative ion produced by one electron reduction of oxygen gas. Able to be oxidised to oxygen or further reduced into hydrogen peroxide (Villamena 2013). Occurs in nature during oxidation of haemoglobin to methaemoglobin | 10−5 s half-life in physiological conditions (Villamena 2013) | Involved in HOCl and ONOO apoptosis-inducing pathways (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a). Precursor in formation of other highly reactive species (Villamena 2013). Involved in coagulation with NO (Kong et al. 2009) |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | Relatively stable, weak acid with strong oxidising properties Functions as cellular messenger by oxidising intracellular thiols (Villamena 2013), and plays an important role in cellular oxidation and cancer development. | >minute half-life in physiological conditions (Villamena 2013) | Reduces intracellular glutathione (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a) Causes lipid peroxidation and protein and DNA damage via oxidation Villamena 2013) |

| Hydroxyl radical (OH•) | The most reactive and short lived of all radical species (Villamena 2013) | <10−9 s half-life in physiological conditions (Villamena 2013) | Causes lipid peroxidation of cell membrane (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a). Reacts via hydrogen abstraction, electrophilic addition and radical-radical reactions. Plays a direct role in initiation of oxidative damage to macromolecules and reacts directly with all four nucleobases (Villamena 2013). |

| Singlet oxygen (1O2) | An excited state of the oxygen molecule, with paired electrons | 10−3–10−6 s half-life depending on solvent (Villamena 2013) | Inactivates membrane catalase which breaks down H2O2 (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a). Only reacts with guanines (Villamena 2013). Causes oxidative stress reacting with nucleic acids, proteins and lipids |

| Nitric oxide (NO•) | Intracellular signalling molecule, precursor to highly oxidising RNS such as ONOO and NO• (Villamena 2013). | 1−10s estimated half- life in physiological conditions Graves (2014). | Increases intracellular RONS levels and damages mitochondria (Kaushik et al. 2018). Important cellular messenger, important in vascular functioning (Song et al. 2014). Involved in coagulation, inflammatory processes, and concentration-dependent reactions with H2O2 to control apoptosis (Kong et al. 2009) |

| Nitrogen dioxide (NO•2) | Radical oxide of nitrogen | <10−6 s estimated hatf-life in physiological conditions Graves (2014) | Reads rapidly with water to form nitrites and nitrates. Reacts via hydrogen abstraction, addition over C=C bonds, oxygen and electron transfer and radical-radical reactions (Villamena 2013) |

| Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) | Formed from the reaction of NO and O2− (Lu et al. 2016). | Rate of radical cleavage < 10−6 s (Villamena 2013) | Involved in apoptosis-inducing signalling pathway (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a) and can react at active sites on proteins causing nitration and protein cleavage resulting in enzyme deactivation. Depletes NO (Song et al. 2014) |

| Nitrite (NO2−) | Produced by phagocytosis reactions, stable, and thus good indirect indicator of NO concentration (Lu et al. 2019). | Minutes, Lu et al. (2019) | Synergistic action with H2O2 (Bauer 2019) |

| Nitrate (NO3−) | Produced by phagocytosis reactions, stable, and thus good indirect indicator of NO concentration (Lu et al. 2019). | Minutes, Lu et al. (2019) | Solvation of HNO3− in water lowers pH via hydrolysis reaction (Lu et al. 2016), which is known to act in synergy with the other reactive species to produce strong bactericidal effects (Lu et al. 2016) |

Wende et al. (2015) provide us with simulated and experimental insights on the effects of gas composition, treatment distance and time delay of indirect application on the type and density of generated reactive species. Duan et al. (2017) have validated the concentration of various reactive species generated from direct gas plasma treatment as a function of penetration depth through pig muscle tissue (see Fig. 4). Most of the species penetrate less than 2 mm into the muscle tissue, showing that direct gas plasma treatment is only shallow. However, upon repeating the experiment and placing different solutions below the muscle slices, Nie et al. (2018) found that the concentrations of reactive species changed in accordance with the composition of the solution. More H2O2 was found to be generated in solutions containing organic molecules (glucose or human serum) and levels of NO2− and NO3− are highest in solutions containing human serum. This indicates that not only do reactive species diffuse through tissue, but reactions occur with the surrounding fluid to affect the species concentrations. Additionally, these findings provide better insight into the synergistic actions proposed by Kurake et al. (2016) and Girard et al. (2016) and highlight the need for greater understanding of RONS activity in various biological contexts in order to achieve reproducible results.

Fig. 4.

The effect of gas plasma treatment time and tissue thickness on reactive species generation in phosphate-buffered saline and water. Graph (a) exhibits the effect of gas plasma treatment on pH in water through varying thicknesses of pig muscle; graphs (b)–(d) reflect the effect of gas plasma treatment on nitrate and nitrite ions together, nitrite ions singly and hydrogen peroxide respectively in PBS through varying thicknesses of pig muscle. Adapted with permission from Duan et al. (2017) and AIP Publishing

As yet, it is unclear how to develop particular combinations of these elements into an optimal treatment protocol, but it is widely observed that there is a dose-response relationship; that is, increased gas plasma treatment time increases the effectiveness of the solution (Lafontaine et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2019; Tanaka et al. 2019; Takeda et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Tanaka et al. 2011). Yan et al. (2016) showed that specific components in cell culture medium cause degradation of some of these reactive species, as does foetal bovine serum (Kaushik et al. 2018), but this does not happen with simpler solutions such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Differing opinions exist about the lifespan of different activated solutions, with some reports (Tanaka et al. 2011) indicating that the lifetime of gas plasma–activated medium is between 8 and 18 h, though Yan et al. (2016) report significant H2O2 degradation in gas plasma–activated medium after three days in storage at cold temperatures. Conversely, Tanaka et al. (2016) found that PBS frozen at temperatures lower than − 80 °C retained its cancer-killing effects for 3 months and that three freeze-thaw cycles of gas plasma–activated lactate solution frozen at – 150 °C retained similar levels of H2O2 as freshly treated solutions. These differences may arise from different methods of determining the ‘lifetime’ of the solution. Levels of H2O2 and cell killing ability as measured by an assay such as the MTT assay which measures cell viability and proliferation, are two such methods. Cell killing ability is a more decisive endpoint and gas plasma treatment time is a key variable that needs to be controlled.

Apoptosis is the programmed death of a cell in an orderly closing down process leading to clearance by the immune system, whereas necrosis is premature and unplanned cell death which results in loss of membrane integrity and release of cell contents into the extracellular areas. Evidence continues to accumulate to implicate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in gas plasma–mediated selective apoptosis of cancer cells (Sato et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Welz et al. 2015; Ishaq et al. 2015), though there is evidence of gas plasma induction of necrosis (Akhlaghi et al. 2016; Virard et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2010), and evidence also that the line between apoptosis and necrosis is dose-dependent (Chauvin et al. 2019; Hirst et al. 2015; Fridman et al. 2007). It is possible that the transition from apoptosis to necrosis is dependent on the gas plasma source, but this is difficult to determine given the great variety of gas plasma devices employed in these experiments. For an in-depth coverage of the mechanisms of gas plasma–induced cell death and the effects on the tumour microenvorinment, the reader is referred to the extensive reviews of Privat-Maldonado et al. (2019a) and Semmler et al. (2020).

Some mechanisms by which RONS exert their effects in cancer cells are described briefly here. By virtue of the differences in metabolism and protein translation between malignant and non-malignant cells, cancer cells normally have a higher level of intracellular RONS and a higher baseline of oxidation-reduction reactions than non-malignant cells. Thus, cancer cells have to work harder to maintain adequate antioxidant levels to prevent apoptosis. If the level of intracellular RONS is increased further, the antioxidant genes are unable to increase production to protect the cancer cells, and cancer cell–selective apoptosis occurs (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019a; Graves 2012).

The free radical molecule nitric oxide, NO•, is known to cross the cell membrane, causing mitochondrial damage and increasing the level of intracellular ROS (Kaushik et al. 2018). Singlet oxygen, an excited state of the oxygen molecule, inactivates the antioxidant enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase, which sensitises cancer cells to attack by hydroxyl radicals (Schuster et al. 2018). OH• is known to attack the cell membrane, causing lipid peroxidation and apoptosis (Villamena 2013). H2O2 is reportedly able to enter the cell through aquaporins, which are more highly expressed in cancer cells than normal cells, allowing more ROS to enter the cell and induce apoptosis via oxidative stress (Xiang et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2017). Differences in cell membrane composition may also be a factor in selective effects of RONS in cancer therapy. A recent study demonstrated that the level of RONS ingress into vesicles was dependent upon the level of saturated (only single carbon-carbon bonds) and unsaturated (at least one double carbon-carbon bond) phospholipids in the vesicle bilayer (Van der Paal et al. 2019). Unsaturated bonds are more readily oxidised by RONS, which begin to increase the polarity of the membrane and further facilitate RONS passage through the membrane. Cancer cells have been shown to have higher concentrations of phosphatidylethanolamine, which was also shown in this experiment to facilitate RONS entry into vesicles with already high levels of unsaturated phospholipids forming the bilayer. Additionally, the presence of phosphatidylethanolamine in vesicles with only saturated phospholipids forming the bilayer had a protective effect on RONS permeation. Peroxidation of the phospholipids in the bilayer can lead to initial membrane rigidity and increased fluidity. This peroxidation may lead to alterations in the structure, dynamics and assembly of the plasma membrane, facilitating pore formation and entry of more RONS into the cell (Privat-Maldonado et al. 2019b).

Treatment with gas plasma and gas plasma–activated media has been shown to increase caspase-3, caspase-7 (Utsumi et al. 2013; Tanaka et al. 2011) and caspase-9 levels (Liu et al. 2019), which are involved in the apoptosis signalling pathways. Adhikari et al. (2019) found evidence of impaired DNA repair mechanisms and increased expression of apoptosis-inducing genes and decreased levels of cell survival signalling molecules, also found by Tanaka et al. (2011). Changes in cellular signalling in triple-negative breast cancer cells were reported, with a reduction in levels of JNK/MAPK, an important proliferation pathway that is already upregulated in these cells. Recently, Tanaka et al. (2019) compared gas plasma–activated medium with gas plasma–activated Ringer’s lactate solution on glioblastoma cells. Greater ROS production was found in the medium than in lactate solution and although expression of antioxidant genes was not changed in either group, activated medium did induce increased expression of stress-related apoptosis-inducing genes. On the other hand, activated lactate downregulated survival and proliferation signalling networks. (For a more comprehensive description of the pathways and effects, the reader is referred to Privat-Maldonado et al. (2019a).)

Whilst some of the mechanisms of reactive species produced by gas plasmas are understood, the increased effects of gas plasma–activated solutions compared with solutions of individual reactive species have not been fully explained. This could be due to a myriad of intermediates or other short-lived species not easily experimentally detectable, or unknown reactions with the components of the solutions. This gap in our knowledge is particularly important to fill, as unknown reactive species may result in undesirable off-target effects upon the body.

What are the effects on healthy cells?

The effects of gas plasma treatment on healthy cells constrain the dose that can be given. Effective cancer treatments are those with a high therapeutic ratio, being the ratio of effect on cancer cells compared with that on healthy cells. In more precise terms, borrowing a definition from radiotherapy, the therapeutic ratio is the ratio of the doses for a nominated response level for cancerous cells relative to normal cells (Willey et al. 2016, Fig. 5). Key to evaluating the therapeutic ratio for gas plasma treatment is to determine the effects on normal cells. Our understanding of the effects of gas plasma on normal cells is from in vitro experiments and from animal studies. Many cell-based experiments show that gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solutions have a selective apoptosis-inducing effect on cancer cells when compared with that on normal cells (Xiang et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2018; Mohades et al. 2016; Tanaka et al. 2011). As Kaushik et al. 2018 importantly pointed out, there is still a limit to which healthy cells can withstand the increased concentration of ROS from gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solutions. Kurake et al. (2016) found selectivity for human glioblastoma over normal human breast epithelial cells, though negative effects on the normal cells began to appear at treatment times of the medium of 180 seconds, at which point all glioblastoma cells were dead. Experimental cell survival was quantified further by Mohades et al. (2017), who reported 90% cell death in squamous cell carcinoma treated with 4-min exposed medium, but only 20% decrease in healthy canine kidney cell viability with a 6-min exposed medium. To kill 100% of the healthy cells, the medium needed to have been exposed for 10 min. Figure 6 illustrates the difference in cell viability for the tumour and normal cells.

Fig. 5.

Therapeutic ratio is the ratio of the doses for a nominated response level for cancerous cells relative to normal cells

Fig. 6.

Experimental data showing the differential sensitivity to treatment with gas plasma–activated medium for urinary bladder squamous cell carcinoma (ScaBER cells) and non-cancerous canine kidney epithelial cells (MDCK). Reproduced with permission from Laroussi (2018) from the original data in Mohades et al. (2016)

Such a large therapeutic ratio in vitro is a positive indication for a therapeutic ratio that can be exploited for cancer treatment in vivo. However, a recent experiment from Biscop et al. (2019) points out that selectivity can only be properly determined when cell type, cancer type and medium type are all taken into account. It was found the selectivity of gas plasma–activated PBS treatment was influenced by medium type, not by the differences between cancer cells and normal cells, and the reduction in cell proliferation rates was not appreciably different for healthy and malignant cells of the same type when cultured in the same medium. This was attributed to the fact that different cell types have different gene expression levels which respond differently to gas plasma treatment, and more advanced cell culture media types have higher levels of organic molecules and ROS scavengers. The effect of the choice of medium on cell viability was less pronounced for direct gas plasma treatment, as the medium was removed before application of the gas plasma. Consequently, the authors argue that selectivity lies in the optimisation of conditions to produce enough RONS to overwhelm malignant cells without overwhelming healthy cells. This is an important factor to consider when conducting cell culture experiments. Cell culture experiments are an informative and versatile experimental model and provide great insight into the effects and mechanisms of cancer treatments.

What do we know about the in vivo effects?

Mice are a useful model for investigation in vivo due to their rapid reproductive rate, small size and relative ease of care and housing. The mouse has become a well-established model for biomedical investigation and is commonly used to investigate genetics, neuroscience, disease mechanisms and new drug targets. BALB/c mice are the most commonly used in cancer investigations, as they are easy to breed, immunodeficient and inbred so that each mouse is essentially genetically identical and they are prone to developing tumours (Johnson 2012). These characteristics allow researchers to use human cancer cell lines in their investigations in mice, particularly important for the development of new cancer treatments. Many of the following experiments have used BALB/c mice with human cancer cell lines to judge the effectiveness of gas plasma–activated solutions on different cancer types. Gas plasma–activated solutions have been shown to be effective in mouse models against ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer and melanoma, with both direct injection into the tumour and with intraperitoneal injections.

In a mouse model of xenografted NOS2 and chemoresistant NOS2 human ovarian cancer cells, it was found that 200 μL of gas plasma–activated medium (PAM) injected directly into to each tumour three times weekly for 28 days resulted in 66% reduction in NOS2 tumour size and 52% reduction in chemoresistant NOS2 tumour size, with no toxicity, necrosis or anaphylaxis observed (Utsumi et al. 2013). In a model investigating intraperitoneal ES2 human ovarian cancer, the cells were injected, followed with an injection of PAM 15 min later, once per day for 3 days. It was found that the survival of the treatment group, which was analysed for 90 days post cancer cell injection, was much higher after 3 days of treatment than the control group which received no treatment. The control group reached 100% mortality after 35 days post cell injection, whereas the treatment group reached only 60% mortality during the experiment (Nakamura et al. 2017).

Gas plasma–activated medium has shown good selectivity for established G361 human melanoma tumours in mice. When the tumour reached a volume of 100 mm3, the mice were treated with 200 μL of PAM injected directly into the tumour for 4 days. The tumour size and weight decreased compared with that of the control group (Adhikari et al. 2019). Liu et al. (2019) examined the effectiveness of gas plasma–activated saline (PAS) treated for a range of times on B16 rodent melanoma tumours. The tumours were allowed to grow subcutaneously on the back of the mice for 7 days before treatment began. 200 μL PAS or untreated saline was injected daily directly into the tumour for 14 days. From the 5-min gas plasma treatment group which was the longest treatment time in this study, tumour size was found to decrease by 78.8%. In the 4- and 5-min groups, it was noted that festering and ‘crusts’ occurred, indicating that time of treatment is an important factor.

Gas plasma–activated Ringer’s lactate solution (PAL) was found to be effective in reducing the number of metastatic nodules of human pancreatic cancer in mice treated with an intermittent dosing regimen (Sato et al. 2018). Intermittent administration of PAM delayed pancreatic tumour formation when commenced 24 h after cancer cell injection, also reducing the overall tumour volume (Hattori et al. 2015). PAM administered intraperitoneally for up to 35 days was effective against established rodent pancreatic tumours (Liedtke et al. 2017). The tumours were assessed after 21 days of treatment, and treatment was found to have reduced tumour size by 21% and weight by 31% compared with that of the control group. The mice in the treatment group survived longer, even after finishing their treatment, and no evidence was found of increased inflammatory markers or indicators of systemic side effects. Interestingly, evidence was found of apoptosis not only on the tumour margins but also within the tumour itself. No evidence of apoptosis in a healthy liver or gut tissue indicated good selectivity in vivo, which is highly desirable for translation. A similar dosing regimen to Hattori et al. (2015) was found to be effective against the development of gastric cancer metastases (Takeda et al. 2017). Only 40% of mice in the treated group compared with 100% of mice in the control group developed metastatic nodules with no indications of peritonitis, organ damage or differences in diet or weight.

Xiang et al. (2018) determined that PAM had a greater effect on established triple-negative breast cancer tumours than on non-triple-negative breast cancer when mice were administered with two injections of 100 μL directly into the tumour every second day for 29 days. In another experiment, a comparison of direct physical gas plasma application and gas plasma–activated PBS was made on established triple-negative breast cancer tumours in mice (Zhou et al. 2020). Treatment consisted of 5 min of physical gas plasma application directly inside the tumour from their gas plasma pen device, or two injections of 100 μL of gas plasma–activated PBS every 72 h for 30 days. All of the mice in the control group, which received no treatment, died by day 27; three mice from the PBS treatment group died by day 30; and all mice from the gas plasma pen group survived until the end of the study. Both treatments were effective at reducing tumour growth and proliferation, despite the differences in survival rate. Both effectively returned tumour-affected renal function, and immune and inflammatory markers back to normal, though the gas plasma pen was slightly more effective than the PBS in this regard. Ikeda et al. (2018) found PAM to be effective against cancer-initiating cells with daily intra-abdominal injections. However, it is difficult to quantify how effective this was as the tumour sizes themselves were estimated only via abdominal palpation.

Dehui et al. (2018) investigated the effects of gas plasma–activated water administered by oral lavage three times daily for 2 weeks, as well as acute toxicity effects on immune-compromised mice with no cancer. Two treatment groups, consisting of six mice each, were treated three times daily with water activated for either 2 or 4 min. To measure the acute toxicity effects, another group of six mice was treated three times daily for 2 days with water that had been activated for 15 min. The solution treatment times were similar to those giving therapeutic effect as discussed above. The effects of the gas plasma–activated water on general wellbeing, mental state, behaviour, diet, renal activity and weight were monitored. Tissue examinations on vital organs and monitoring of effects on blood and serum effects were performed. In both groups, no negative effects were found on the lung, heart, liver, spleen or kidneys; no changes were observed in kidney function, electrolyte balance, glucose or lipid metabolism. The only effect that could be found in the blood analysis was that of increased monocyte and neutrophil levels, indicating that gas plasma–activated water treatment-induced immune responses in immune-compromised mice. Despite the absence of any organ damage, an immune response in immune-compromised mice is highly favourable. The two key distinctions between this study and others providing therapeutic evidence is that different liquid media were activated and a different method of administration was used.

Whilst these results are very promising as a potential new cancer treatment or adjuvant therapy, it is obvious from the diverse array of methodologies described above that there are many unanswered questions that need investigation before gas plasma treatment can be translated to clinical practice. Each experiment used a different type of solution, a different plasma system, different treatment volumes and dosing regimens; the development of a standardised dose and dosing regimen is imperative for translation. Gas plasma–activated solution treatments have been shown to be effective at reducing the metastatic potential of pancreatic and gastric cancers, but to date, it is unknown if this treatment is capable of achieving full remission. How treatment with gas plasma affects tumour reappearance, whether or not it may have a preventative effect, as well as side effects of long-term gas plasma–activated solution treatment, still remain to be determined. Liu et al. (2019) observed that for long treatment times of saline solution, there was localised necrosis. No other study has reported negative side effects, despite most using similar, if not longer solution activation times. Due to the small number of experiments utilising saline, it is yet unknown if this is a feature specifically of gas plasma–treated saline solution, or if there may be other factors at play. Some experimental designs display effectiveness in preventing metastasis and delaying tumour growth with early administration of activated solutions; however, it is somewhat unclear how effective this treatment would be on already established pancreatic and gastric metastases. We recommend that optimisation of gas plasma–activation settings and development of treatment protocols need to be thoroughly evaluated and adapted for use in clinical situations. It is vital that a common set of solutions and administration procedures be used in future work to enable the therapeutic ratio for these treatments to be thoroughly evaluated. So far, the results from mouse experiments have been promising, but there is still much work to be done before gas plasma–activated solution treatments are able to be translated into human trials.

Devices and clinical trials

Physical gas plasma devices are already available for applications in dermatology, dentistry and in surgery. These devices utilise two types of gas plasma: a spark discharge and a glow discharge. A spark discharge is a class of gas plasma discharge, where the gas is heated significantly above ambient temperature by the passage of a relatively high current density in a localised filamentary type of discharge. There may be some ablation of material from the usually conductive surface that acts as a source of the discharge. A spark discharge in gas (see Fig. 2) at atmospheric pressure is usually generated by a high voltage, creating an avalanche discharge when the electric field in the gap between two conductors exceeds a breakdown value.

When a spark discharge is operated in an aqueous environment, the rapid delivery of heat by ohmic dissipation to a localised region of the liquid often generates vapour bubbles in a process known as cavitation. After formation by the spark discharge, the bubbles rapidly cool and collapse, leading to the mechanical application of pressure to surrounding objects (Palanker et al. 2001). When used in contact with tissue in surgery, a spark discharge may have cutting capabilities, where the mechanical forces of cavitation sever the tissue and under suitable conditions create a neat cut with minimal heat damage to surrounding tissue. Spark cutting in surgery is similar in some respects to laser cutting where the local energy is delivered by a laser beam. When more powerful spark discharges are used, the gas plasma becomes hotter enabling the cauterisation of blood vessels to stem the flow of blood during surgery.

The PEAK PlasmaBlade from Medtronic is an example of a clinical application of the spark discharge type of device in cancer surgery (see Figs. 7 and 8). It has been used for a range of surgeries, including mastectomies and malignant lumpectomies. However, compared with traditional electrosurgery and use of a surgical scalpel, the gas PlasmaBlade results in a 74% reduction in thermal injury depth, less severe scarring, improved wound strength and reduced inflammatory response during incision (Schlosshauer et al. 2020; Ruidiaz et al. 2011b). Chiappa et al. (2018) found in their preliminary trial that the PlasmaBlade reduced the incidence of seroma formation after breast cancer surgery, whilst Dogan et al. (2013) found a statistically significant reduction in the drainage volume and duration when compared with traditional electrocautery. No significant differences between groups for operation duration, blood loss, seroma, hematoma, surgical site infection, flap necrosis or time to starting arm exercises were reported by Dogan et al. In contrast, Alptekin et al. (2017) reported the PlasmaBlade resulted in an increase in drainage duration and volume from the surgical site when compared with electrocautery.

Fig. 7.

Image of the PlasmaBlade generating gas plasma streamers. Reproduced with the permission from Palanker et al. (2001) and permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Fig. 8.

Stylised rendering of the cutting ability of the PlasmaBlade. See https://europe.medtronic.com/xd-en/healthcare-professionals/products/general-surgery/electrosurgical/peak-plasmablade-device.html. Copyright ©2020 Medtronic. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission

The PlasmaBlade has also been used in a pilot study of 20 patients to determine the effect on tumour margins and thermal damage in malignant breast lumpectomies Ruidiaz et al. (2011a). The PlasmaBlade reduced collagen denaturation depth, fused tissue depth and distortion depth, all of which affect the classification of tumour margins and thus the determination of future treatment plans for that patient. This is particularly important for the prevention of false determinations of tumour margins which affect the prescription of post-surgical radiation, as large sections of unreadable tissue may mask the presence of remaining cancer cells. The impact of the PlasmaBlade is reduced hospital stay and faster healing to enable the patient to move on to other treatments. A glow discharge is a cooler and more extended type of discharge created in a gas when the breakdown electric field is applied. There are two convenient electrode configurations for forming a glow discharge in a gas flowing through a small diameter capillary tube to create an atmospheric pressure gas plasma jet. One configuration has two electrodes around the outside of the capillary, and the other has one electrode outside the capillary and the other electrode inside and coaxial with the capillary (see Fig. 2). Pulses of direct current are applied between the electrodes at a frequency that can be varied over a wide range. Alternatively, a continuous sine wave signal can be applied. In air, such discharges create a wide variety of reactive species that arise from the interactions of the electrons in the discharge with air molecules. As discussed in the ‘What is gas plasma and what is gas plasma–activated solution?’ section, the concentration and types of radicals made depend on the gas (Barni et al. 2014), the duration of operation and power supply (Lu et al. 2016).

The kINPen is an example of a coaxial glow discharge gas plasma device that is being used for clinical applications; it has been licensed for treatment of infective skin diseases and infected wounds since 2013 (Metelmann et al. 2015) and has been shown to have significant effects on locally advanced head and neck cancer a schematic of which can be found in Schuster et al. (2016). Schuster et al. (2016) agree with Metelmann et al. (2015) in that patients displayed good tolerability to the gas plasma treatment, reduction in odour, reduced need for pain medication and improved weight in some cases, with the worst side effects reported to be bad taste and exhaustion. This is attributed to the selective effect on the bacterial load of the ulcerated tumours, which does not harm the surrounding healthy tissue (Schuster et al. 2018). Additionally, the treatment itself is painless, leading to reduced need for anaesthesia and the device is portable which leads to more versatility for treatment locations. Metelmann et al. (2018) found that two patients showed an 80% reduction in tumour size from direct gas plasma treatment, five patients reported significantly improved odour from the infected ulcer and four showed less demand for pain medication. Unfortunately, it must be noted that in this study, only one of the six participants (one of those who showed 80% reduction in tumour size) survived to see the completion of the study. Of the other four participants, three did not exhibit improvement in tumour size, and one experienced no change up until their exit from the study.

The Canady Helios Plasma Scalpel is a flexible device that can be used to generate either a spark discharge for surgery or a glow discharge for gas plasma jet treatments (Fig. 9). A clinical trial, number NCT04267575, is currently being conducted using the Canady Helios Plasma Scalpel device at the surgical margin and macroscopic tumour sites, where the gas plasma will be sprayed into the area of the resected tumour margin after removal, with the aim to selectively target residual malignant cells (see Fig. 10). A similar device is the J-Plasma from Apyx Medical, which is under investigation for use in the dissection and sealing of lymphatic channels (number NCT02658851).

Fig. 9.

Canady hybrid scalpel device. Reproduced from https://www.usmedinnovations.com/products-technology/canady-hybrid-plasma-technology/

Fig. 10.

Canady hybrid scalpel in (a) scalpel mode (hot), (b) gas plasma mode (cold) and (C) argon plasma coagulator mode (hot). Reproduced from Ly et al. (2018)

A single device that is able to perform ablation and cauterisation as well as selectively target malignant cells in an intraoperative setting could be highly beneficial for cancer surgery. Additionally, the increased portability and versatility of treatment devices could be important to increase the availability of cancer treatment in geographically remote locations.

How does gas plasma treatment relate to existing cancer treatments?

To date, treatment with cold gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solution appears to be very well tolerated in clinical and preclinical trials. Dehui et al. (2018) report an upregulation of immune cell expression, whilst others report no detrimental effects in terms of mouse weight loss between treatment and control groups (Nakamura et al. 2017; Tanaka et al. 2016). Schuster et al. (2016) report mild to moderate side effects with good general tolerability and even weight gain in human patients undergoing cold gas plasma treatment. The absence of reported side effects is encouraging, given the known side effects in many existing cancer treatments. Surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy are the most common treatments for cancer today. Each has their individual benefits and drawbacks. Surgery is invasive, though effective at removing solid tumours. Chemotherapy is relatively simple to administer, though the side effects of the systemic nature of the treatment can make adherence and re-treatment difficult for the patient. Ionising radiation, when delivered to known doses and following a clear treatment regimen, is lethal to living tissue and for this reason radiation therapy clinical practice places a focus on the volumetric distribution of dose in the body and the control of the amount and timing of dose administration. The similarities between gas plasma and ionising radiation in their generation of reactive species and induction of DNA strand breaks indicate that gas plasma could be used as an effective treatment in cancer therapy, but should also serve as a warning that its safety and mechanisms of action need to be predictable and well understood. Radiation causes a multitude of effects including those on the lungs, heart, skin, intestine, kidney, immune function and nervous system in addition to the death of cancer cells. In radiation therapy, direct targeting of DNA molecules results in death, mutation or aberrations upon the breakage of DNA strands and indirectly, the generation of radicals upon the radiolysis of water. This radiolysis effect generates reactive species such as hydroxide radicals and solvated electrons, which are able to exert their biomolecule-damaging effects on more than just the target cell by diffusing through neighbouring cells (Selman 1983). In radiation therapy, much work has gone into developing treatment protocols to maximise effects on tumour control and minimise acute and late effects on healthy tissue. For example, larger doses produce fewer side effects, but will effectively control tumour growth when the dose is divided into equal fractions (Hall 1988). This fractionation in dose delivery has a less intense immunosuppressive effect than singular doses. Although there is evidence that radiation inhibits antibody formation and phagocytic action of macrophages, increasing risks of bacterial infection in the patient (Selman 1983), in gas plasma treatment, such immunosuppressive effects are not seen at this stage; it may in fact encourage an immunostimulatory effect (Dehui et al. 2018). Gas plasma treatment may therefore have an advantage over traditional radiation therapy for some cancer treatments.

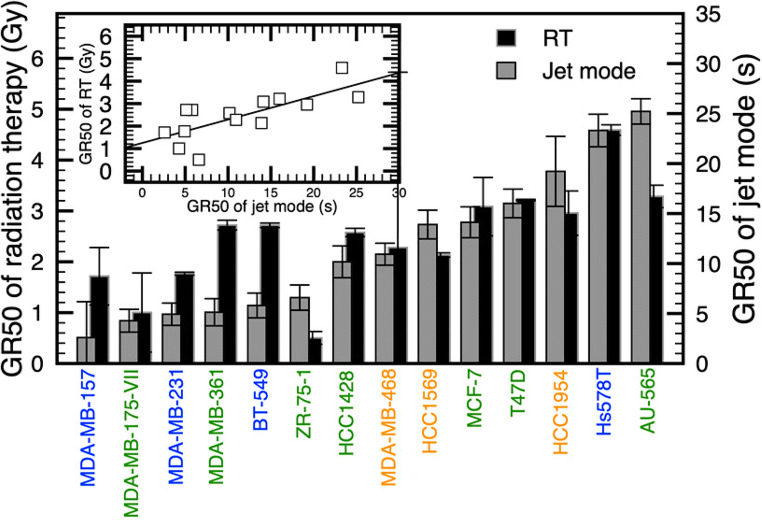

A recent paper by Lafontaine et al. (2020) makes a direct comparison between cold gas plasma treatment and radiation on a large range of breast cancer cells in vitro, in addition to examining any effects of these two treatment modalities applied both together and separately with the chemotherapy drug olaparib. It was determined that the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiation therapy was well correlated with sensitivity to direct gas plasma application (see Fig. 11), and synergistic action between radiation and gas plasma application was found in a subset of cancerous cells. Co-administration of both gas plasma and radiation separately with olaparib was found to have similarly enhanced effects compared with their respective single therapies, indicating that co-treatment with olaparib may be an effective way to improve both gas plasma and radiation treatment responses without an increase in side effects. Effects of these treatments remain to be seen on normal cells and in vivo; however, this is an encouraging step towards improved outcomes for already available treatments.

Fig. 11.

Comparison of the dose required for gas plasma and radiation to induce a 50% reduction in growth rate (GR). GR metrics allow the generation of dose-response curves that are not influenced by the division rate. Adapted with permission from Lafontaine et al. (2020)

How do we know what dose to give?

Hot gas plasmas are able to induce hyperthermia, the increase in body temperature. Inducing hyperthermia in a tumour prior to radiation therapy is known to have clinical benefits; however, its clinical practice is constrained by the ease with which controlled and steady heating of the target tissue, supplied by a circulating system, increases the local temperature and in combination with radiotherapy may lead to improved clinical outcomes Datta et al. (2016). However, this application of hot gas plasmas is at a very early stage and will not be further discussed here.

The application of cold gas plasma in cancer treatment has been demonstrated; however, the remaining concerns relate to the delivery mode and dose optimisation. In the literature, the concept of a relative dose is made simply in terms of the time of exposure to the gas plasma. However, the definition of an absolute dose is needed in order to permit comparative studies and ensure reproducibility and accuracy of treatment. An absolute dose could be defined in terms of the concentration of specified reactive species created but has not yet been universally agreed upon. The dosimetry for the treatment using direct gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solution will be influenced by numerous variables. At present in the literature, the ‘dose’ that is referred to most commonly is the relative dose. The use of the kINPen in the reduction of head and neck tumour size, and its dose tolerability, is encouraging, providing early evidence that this treatment protocol is safe and effective. However, more needs are to be learned about the effects on tumours in different stages and the effects on different cancer types. The clinical trial of the Canady Plasma Scalpel, which has not yet matured, will provide much-needed data on the effectiveness and drawbacks of intraoperative gas plasma treatment for cancer cytoreduction. A recent paper by Ji et al. (2019) correlated the ROS production from both radiation and gas plasma jet in vitro. Approximately equivalent doses were calculated based upon ROS production both in the medium and inside the cells themselves. This data and the work from Lafontaine et al. (2020) (see Fig. 11) provides important information for future in vitro work that could pave the way for similar radiation and gas plasma dose comparison work in vivo.

Currently, there is no established gas plasma treatment regimen for activated solutions, but a predictable and repeatable general dose-response relationship does appear to exist. Dose-response relationships are a key principle in therapeutic interventions, as excessive doses can be more detrimental than beneficial. It is imperative for clinical translation that a standardised treatment regimen is developed, in order to reliably deliver consistent concentrations of active species to patients for treatment. The doses at which gas plasma–activated liquids become harmful to healthy cells has been identified in cell culture but has not yet been determined in in vivo models. This, along with an understanding of the effects of long-term administration and after effects, is a barrier to be overcome prior to patient treatment. That being said, the large therapeutic ratio displayed in cell culture experiments indicates that a large therapeutic ratio in animal models could also be achieved. Given that most cancer treatments have side effects, key question is whether the side effects are outweighed sufficiently by the therapeutic benefits to the patient.

Delivery challenges for translation into the clinic

Some of the key issues for translation of cold gas plasma and gas plasma–activated solutions are in their delivery modes. Since direct application of cold gas plasma is effective at short ranges, direct gas plasma treatment may not be easily achieved in cases where access is difficult. A device designed to facilitate the application of cold gas plasma to the brain or breast tissue demonstrated that the anti-cancer potency is decreased with increasing length of the gas plasma plume Chen et al. (2018). Consequently, direct application of cold gas plasma may only be appropriate for easily accessible tumours. Intraoperative cold gas plasma application may have its own inherent constraint, since to deliver sufficient dose, the time required may be inconvenient during surgery. For clinically compatible intraoperative treatments where the dose in the single treatment opportunity may be high, cold gas plasma devices need to have a high dose rate which may require device redesign.

Administration of gas plasma–activated solutions may be difficult in patients who have aversions to injections, though this could be a definitive advantage for long-term administration to inaccessible areas or for cancers with high metastatic potential. It is not uncommon for cancer patients receiving repeat medication to have an in situ cannula, enabling medication to be delivered at repeat and regular intervals, without repeat injections. For injection of activated solutions, the safety of cell culture medium in humans is as yet unclear, but storage data indicates that simpler solutions such as saline and water, which are already deemed safe for use in humans, experience decreased degradation of reactive species over time. The anti-cancer potency of saline solutions remains steady through several freeze-thaw cycles and in cold storage for several months. Practically, this type of treatment has significant advantages for the treatment of cancers in regional centres where access to comprehensive cancer treatment facilities may be limited. Thus, gas plasma treatment has several opportunities to act either directly or indirectly through activated solutions in the treatment of cancer, especially for patients with limited access to conventional treatment.

Where does the research need to go from here?

Gas plasma technology for surgery is relatively mature and has found a niche application for coagulation to avoid excessive bleeding. An exciting development is the recognition of gas plasma instruments in precision cutting to minimise tissue damage, improve recovery and reduce complications. An even more exciting development is the use of gas plasma technology for cancer treatment, with emerging evidence that cancer cells respond differently to normal cells when exposed to gas plasma, either directly or indirectly. The underpinning science is still in active development with important questions remaining. Synergies appear to exist between reactive species, but mechanisms and the most effective synergy combinations still remain to be fully understood. The synergy found by Lafontaine et al. (2020) between gas plasma and radiation therapy and gas plasma and a chemotherapeutic agent (supported by Xu et al. 2019) provides evidence for further opportunities to improve cancer treatments. For example, the evidence for gas plasma–induced immunogenic cell death indicates that gas plasma treatment could also be an avenue for combination therapy research with immunotherapy (Azzariti et al. 2019).

For clinical translation of gas plasma medicine to the treatment of cancer, safe and effective treatment protocols with supporting technology need to be developed. To achieve this, scientists and clinicians need to collaborate to design clinical trials with endpoints that can identify and quantify the benefits and risks of gas plasma treatments. An advantage of gas plasma cancer therapy is its ability to be applied both by direct exposure and by indirect exposure via gas plasma–activated solutions. Even though accessibility of the site to gas plasma treatment may initially appear to be a challenge, clinical presentations have specific requirements which may benefit from different treatment modalities. For example, the tumour bed following excision can be treated directly with cold gas plasma, whilst the pleural or the peritoneal cavities may be better treated indirectly with gas plasma–activated solution.

Among clinicians, there appears to be a relative unfamiliarity with gas plasma technology and its potential benefits. The way forward is closer collaboration between clinicians and scientists, enabling the development of clinical trials for specific cancers and specific patient presentations. Successful outcomes would enable gas plasma therapies to become one of the spectrum of available tools for customising treatments for individual cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to graphic designer Maria Mora for her work on Figs. 2 and 5.

Funding information

The Australian Government funded the Chris O’Brien Lifehouse Sarcoma Research Centre. Financial support is acknowledged from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council though NHMRC grant number APP1183597 (IRMA ID: 205916).

This work has been supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program scholarship.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adhikari M, Adhikari B, Kaushik N, Lee S-J, Kaushik NK, Choi EH. Melanoma growth analysis in blood serum and tissue using xenograft model with response to cold atmospheric plasma activated medium. Appl Sci. 2019;9(20):4227. [Google Scholar]

- Akhlaghi M, Rajaei H, Mashayekh AS, Shafiae M, Mahdikia H, Khani M, Hassan ZM, Shokri B. Determination of the optimum conditions for lung cancer cells treatment using cold atmospheric plasma. Phys Plasmas. 2016;23(10):103512. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida ND, Klein AL, Hogan E, Terhaar SJ, Kedda N, Uppal P, Sack K, Keidar M, Sherman JH (2019) Cold atmospheric plasma as an adjunct to immunotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme. World Neurosurg [DOI] [PubMed]

- Alptekin H, Yılmaz H, Ozturk B, Ece I, Kafali ME, Acar F (2017) Comparison of electrocautery and plasmablade on ischemia and seroma formation after modified radical mastectomy for locally advanced breast cancer. Surg Tech Dev 7(1)

- Alrehaili AA, AlMourgi M, Gharib AF, Elsawy WH, Ismail KA, Hagag HM, Anjum F, Raafat N. Clinical significance of p27 kip1 expression in advanced ovarian cancer. Appl Cancer Res. 2020;40(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Azzariti A, Iacobazzi RM, Di Fonte R, Porcelli L, Gristina R, Favia P, Fracassi F, Trizio I, Silvestris N, Guida G, et al. Plasma-activated medium triggers cell death and the presentation of immune activating danger signals in melanoma and pancreatic cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40637-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barni R, Biganzoli I, Tassetti D, Riccardi C. Characterization of a plasma jet produced by spark discharges in argon air mixtures at atmospheric pressure. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2014;34(6):1415–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G (2019) The synergistic effect between hydrogen peroxide and nitrite, two long-lived molecular species from cold atmospheric plasma, triggers tumor cells to induce their own cell death. Redox Biology 26:101291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Biscop E, Lin A, Van Boxem W, Van Loenhout J, De Backer J, Deben C, Dewilde S, Smits E, Bogaerts A. The influence of cell type and culture medium on determining cancer selectivity of cold atmospheric plasma treatment. Cancers. 2019;11(9):1287. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg R. Dielectric barrier discharges: progress on plasma sources and on the understanding of regimes and single filaments. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2017;26(5):053001. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin J, Gibot L, Griseti E, Golzio M, Rols M-P, Merbahi N, Vicendo P. Elucidation of in vitro cellular steps induced by antitumor treatment with plasma-activated medium. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41408-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Simonyan H, Cheng X, Gjika E, Lin L, Canady J, Sherman JH, Young C, Keidar M. A novel micro cold atmospheric plasma device for glioblastoma both in vitro and in vivo. Cancers. 2017;9(6):61. doi: 10.3390/cancers9060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Lin L, Zheng Q, Sherman JH, Canady J, Trink B, Keidar M (2018) Micro-sized cold atmospheric plasma source for brain and breast cancer treatment. Plasma Med 8(2)

- Chiappa C, Fachinetti A, Boeri C, Arlant V, Rausei S, Dionigi G, Rovera F. Wound healing and postsurgical complications in breast cancer surgery: a comparison between peak plasmablade and conventional electrosurgery–a preliminary report of a case series. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018;95(3):129–134. doi: 10.4174/astr.2018.95.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta NR, Puric E, Klingbiel D, Gomez S, Bodis S. Hyperthermia and radiation therapy in locoregional recurrent breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94(5):1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehui X, Qingjie C, Yujing X, Bingchuan W, Miao T, Qiaosong L, Zhijie L, Dingxin L, Hailan C, Michael GK. Systemic study on the safety of immuno-deficient nude mice treated by atmospheric plasma-activated water. Plasma Sci Technol. 2018;20(4):044003. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan L, Gulcelik MA, Yuksel M, Uyar O, Erdogan O, Reis E. The effect of plasmakinetic cautery on wound healing and complications in mastectomy. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16(2):198–201. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Lu X, He G. On the penetration depth of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated by a plasma jet through real biological tissue. Phys Plasmas. 2017;24(7):073506. doi: 10.1063/1.4990554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freelove R, Walling A. Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(3):485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund E, Liedtke KR, van der Linde J, Metelmann H-R, Heidecke C-D, Partecke L-I, Bekeschus S. Physical plasma-treated saline promotes an immunogenic phenotype in ct26 colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman G, Shereshevsky A, Jost MM, Brooks AD, Fridman A, Gutsol A, Vasilets V, Friedman G. Floating electrode dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air promoting apoptotic behavior in melanoma skin cancer cell lines. Plasma Chem Plasma Process. 2007;27(2):163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Girard P-M, Arbabian A, Fleury M, Bauville G, Puech V, Dutreix M, Sousa JS. Synergistic effect of h 2 o 2 and no 2 in cell death induced by cold atmospheric he plasma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29098. doi: 10.1038/srep29098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbanev Y, Privat-Maldonado A, Bogaerts A. Analysis of short-lived reactive species in plasma-air-water systems: the dos and the do nots. Anal Chem. 2018;90(22):13151. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves DB. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2012;45(26):263001. [Google Scholar]

- Graves DB (2014) Oxy-nitroso shielding burst model of cold atmospheric plasma therapeutics. Clinical Plasma Medicine 2(2):38–49

- Hall EJ (1988) Radiobiology for the radiologist. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 3rd ed edition. Includes bibliographies and index

- Hamaguchi S (2013) Chemically reactive species in liquids generated by atmospheric-pressure plasmas and their roles in plasma medicine. In AIP Conference Proceedings, volume 1545, pages 214–222. American Institute of Physics. 10.1063/1.4815857

- Hattori N, Yamada S, Torii K, Takeda S, Nakamura K, Tanaka H, Kajiyama H, Kanda M, Fujii T, Nakayama G, et al. Effectiveness of plasma treatment on pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2015;47(5):1655–1662. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst A, Simms M, Mann V, Maitland N, O’connell D, Frame F. Low- temperature plasma treatment induces dna damage leading to necrotic cell death in primary prostate epithelial cells. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(9):1536–1545. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda J-i, Tanaka H, Ishikawa K, Sakakita H, Ikehara Y, Hori M. Plasma- activated medium (pam) kills human cancer-initiating cells. Pathol Int. 2018;68(1):23–30. doi: 10.1111/pin.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq M, Han ZJ, Kumar S, Evans MD, Ostrikov K. Atmospheric-pressure plasma-and trail-induced apoptosis in trail-resistant colorectal cancer cells. Plasma Process Polym. 2015;12(6):574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Ji W-O, Lee M-H, Kim G-H, Kim E-H. Quantitation of the ros production in plasma and radiation treatments of biotargets. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. Laboratory mice and rats. Mater Methods. 2012;2:113. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik NK, Ghimire B, Li Y, Adhikari M, Veerana M, Kaushik N, Jha N, Adhikari B, Lee S-J, Masur K, et al. Biological and medical applications of plasma-activated media, water and solutions. Biol Chem. 2018;400(1):39–62. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Chung T, Bae S, Leem S. Induction of apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by a pulsed atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97(2):023702. [Google Scholar]

- Kong MG, Kroesen G, Morfill G, Nosenko T, Shimizu T, Van Dijk J, Zimmermann J (2009) Plasma medicine: an introductory review. New J Phys 11(11):115012

- Kurake N, Tanaka H, Ishikawa K, Kondo T, Sekine M, Nakamura K, Kajiyama H, Kikkawa F, Mizuno M, Hori M. Cell survival of glioblastoma grown in medium containing hydrogen peroxide and/or nitrite, or in plasma-activated medium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;605:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine J, Boisvert J-S, Glory A, Coulombe S, Wong P. Synergy between non-thermal plasma with radiation therapy and olaparib in a panel of breast cancer cell lines. Cancers. 2020;12(2):348. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroussi M. Plasma medicine: a brief introduction. Plasma. 2018;1(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Laroussi M. Cold plasma in medicine and healthcare: the new frontier in low temperature plasma applications. Front Phys. 2020;8:74. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke KR, Bekeschus S, Kaeding A, Hackbarth C, Kuehn J-P, Heidecke C-D, von Bernstorff W, von Woedtke T, Partecke LI. Non-thermal plasma-treated solution demonstrates antitumor activity against pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-R, Wu Y-M, Xu G-M, Gao L-G, Ma Y, Shi X-M, Zhang G-J. Low-temperature plasma induced melanoma apoptosis by triggering a p53/pigs/caspase-dependent pathway in vivo and in vitro. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2019;52(31):315204. [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Naidis G, Laroussi M, Reuter S, Graves D, Ostrikov K. Reactive species in non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasmas: generation, transport, and biological effects. Phys Rep. 2016;630:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Keidar M, Laroussi M, Choi E, Szili EJ, Ostrikov K (2019) Transcutaneous plasma stress: from soft-matter models to living tissues. Mater Sci Eng R Rep 138:36–59

- Ly L, Jones S, Shashurin A, Zhuang T, Rowe W, Cheng X, Wigh S, Naab T, Keidar M, Canady J. A new cold plasma jet: performance evaluation of cold plasma, hybrid plasma and argon plasma coagulation. Plasma. 2018;1(1):189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Metelmann H-R, Nedrelow DS, Seebauer C, Schuster M, von Woedtke T, Weltmann K-D, Kindler S, Metelmann PH, Finkelstein SE, Von Hoff DD, et al. Head and neck cancer treatment and physical plasma. Clin Plasma Med. 2015;3(1):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Metelmann H-R, Seebauer C, Miller V, Fridman A, Bauer G, Graves DB, Pouvesle J-M, Rutkowski R, Schuster M, Bekeschus S, et al. Clinical experience with cold plasma in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Plasma Med. 2018;9:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mohades S, Barekzi N, Razavi H, Maruthamuthu V, Laroussi M. Temporal evaluation of the anti-tumor efficiency of plasma-activated media. Plasma Process Polym. 2016;13(12):1206–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Mohades S, Laroussi M, Maruthamuthu V. Moderate plasma activated media suppresses proliferation and migration of mdck epithelial cells. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2017;50(18):185205. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Peng Y, Utsumi F, Tanaka H, Mizuno M, Toyokuni S, Hori M, Kikkawa F, Kajiyama H. Novel intraperitoneal treatment with non-thermal plasma-activated medium inhibits metastatic potential of ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L, Yang Y, Duan J, Sun F, Lu X, He G. Effect of tissue thickness and liquid composition on the penetration of long-lifetime reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (rons) generated by a plasma jet. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2018;51(34):345204. [Google Scholar]

- Palanker DV, Miller JM, Marmor MF, Sanislo SR, Huie P, Blumenkranz MS. Pulsed electron avalanche knife (peak) for intraocular surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(11):2673–2678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privat-Maldonado A, Bengtson C, Razzokov J, Smits E, Bogaerts A. Modifying the tumour microenvironment: challenges and future perspectives for anticancer plasma treatments. Cancers. 2019;11(12):1920. doi: 10.3390/cancers11121920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privat-Maldonado A, Schmidt A, Lin A, Weltmann K-D, Wende K, Bogaerts A, Bekeschus S (2019b) Ros from physical plasmas: redox chemistry for biomedical therapy. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruidiaz ME, Cortes-Mateos MJ, Sandoval S, Martin DT, Wang-Rodriguez J, Hasteh F, Wallace A, Vose JG, Kummel AC, Blair SL. Quantitative comparison of surgical margin histology following excision with traditional electrosurgery and a low-thermal injury dissection device. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104(7):746–754. doi: 10.1002/jso.22012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruidiaz ME, Messmer D, Atmodjo DY, Vose JG, Huang EJ, Kummel AC, Rosenberg HL, Gurtner GC. Comparative healing of human cutaneous surgical incisions created by the peak plasmablade, conventional electrosurgery, and a standard scalpel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):104–111. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821741ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Yamada S, Takeda S, Hattori N, Nakamura K, Tanaka H, Mizuno M, Hori M, Kodera Y. Effect of plasma-activated lactated ringer’s solution on pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(1):299–307. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer T, Kiehlmann M, Riener M-O, Rothenberger J, Sader R, Rieger UM (2020) Effect of low-thermal dissection device versus conventional electrocautery in mastectomy for female-to-male transgender patients. Int Wound J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schuster M, Seebauer C, Rutkowski R, Hauschild A, Podmelle F, Metelmann C, Metelmann B, von Woedtke T, Hasse S, Weltmann K-D, et al. Visible tumor surface response to physical plasma and apoptotic cell kill in head and neck cancer. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2016;44(9):1445–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M, Rutkowski R, Hauschild A, Shojaei RK, von Woedtke T, Rana A, Bauer G, Metelmann P, Seebauer C. Side effects in cold plasma treatment of advanced oral cancer—clinical data and biological interpretation. Clin Plasma Med. 2018;10:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Selman J (1983) Elements of radiobiology. Springfield, Ill., U.S.A.: C.C. Thomas. Includes index

- Semmler ML, Bekeschus S, Schäfer M, Bernhardt T, Fischer T, Witzke K, Seebauer C, Rebl H, Grambow E, Vollmar B, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the efficacy of cold atmospheric pressure plasma (cap) in cancer treatment. Cancers. 2020;12(2):269. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Li G, Ma Y (2014) A review on the selective apoptotic effect of nonthermal atmospheric-pressure plasma on cancer cells. Plasma Medicine 4(1–4):193–209

- Szili EJ, Hong S-H, Oh J-S, Gaur N, Short RD. Tracking the penetration of plasma reactive species in tissue models. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36(6):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Yamada S, Hattori N, Nakamura K, Tanaka H, Kajiyama H, Kanda M, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Fujii T, et al. Intraperitoneal administration of plasma- activated medium: proposal of a novel treatment option for peritoneal metastasis from gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(5):1188–1194. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Mizuno M, Ishikawa K, Nakamura K, Kajiyama H, Kano H, Kikkawa F, Hori M (2011) Plasma-activated medium selectively kills glioblastoma brain tumor cells by down-regulating a survival signaling molecule, akt kinase. Plasma Med 1(3–4)

- Tanaka H, Nakamura K, Mizuno M, Ishikawa K, Takeda K, Kajiyama H, Utsumi F, Kikkawa F, Hori M. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma activates lactate in ringer’s solution for anti-tumor effects. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36282. doi: 10.1038/srep36282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]