Abstract

Background

Due to its abnormal morphology and ultrastructure, discoid lateral meniscus (DLM) is prone to tear and degeneration, leading to clinical symptoms. Arthroscopy is the main treatment for symptomatic DLM; however, postoperative outcomes vary widely due to the effects of diverse factors. This research aims to explore the factors influencing postoperative outcomes of symptomatic DLM.

Methods

Patients with DLM who underwent arthroscopic surgery at our hospital from 9/2008 to 9/2015 were enrolled according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Fourteen variables, including sex, body mass index (BMI) and other variables, were chosen as factors for study. Knee function was assessed using the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score. Univariate analyses (Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskall-Wallis rank sum test) and multivariate analyses (ordinal logistic regression) were used to identify the factors that influenced postoperative outcomes. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 502 patients, including 353 females (70.3%) and 149 males (29.7%), were enrolled. The median IKDC score postoperatively (87.4; range, 41.4 ~ 97.7; IQR, 14.6) was higher than that preoperatively (57.6; range, 26.9 ~ 64.9; IQR, 9.7) (P < 0.001). Male sex was predictive of a higher IKDC score (P = 0.023, OR = 1.702). Compared with BMI ≥25 kg/m2, < 18.5 kg/m2 was associated with better IKDC score (P = 0.026, OR = 3.016). Contrasting with age of onset ≥45 years, ≤14 years (P < 0.001, OR = 20.780) and 14 ~ 25 years (P < 0.001, OR = 8.516) were associated with better IKDC score. In comparison with symptoms duration> 24 months, IKDC scores for patients with symptoms duration ≤1 month (P = 0.001, OR = 3.511), 1 ~ 6 months (P < 0.001, OR = 3.463) and 6 ~ 24 months (P < 0.001, OR = 3.254) were significantly elevated. Compared to Outerbridge grade III ~ IV, no injury (P < 0.001, OR = 6.379) and grade I (P = 0.01, OR = 4.332) were associated with higher IKDC score.

Conclusions

Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic DLM is safe and effective, but its clinical efficacy is affected by many factors. Specifically, male sex, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, age of onset < 25 years (especially < 14 years) and symptoms duration < 24 months are conducive to good postoperative outcomes. However, combined articular cartilage injury (Outbridge grade ≥ 2) reduces postoperative effect.

Keywords: Influential factor, Discoid meniscus, Arthroscopy, Clinical effect

Background

The discoid meniscus is a congenital variation of the knee meniscus. Morphologically, the discoid meniscus is wider and thicker than the normal meniscus, resulting in potential instability. In the ultrastructure of the discoid meniscus, the radial and circular collagen fibre systems are reduced and disorganized, and the circular collagen fibres are insufficient in strength and show increased brittleness. These morphological and histological abnormalities make the discoid meniscus liable to tearing and degeneration [1–3].

Clinically, discoid lateral meniscus (DLM) is common. The reported incidence of DLM is 13% in china [4], 16.6% in Japan [5], 10.9% in Korea [6] and 5.8% in India [7]. The prevalence of DLM in the western population ranges from 0.4 to 17% [8]. Patients suffering from bilateral DLM accounts for 79–97% of cases [9].

Symptomatic DLM, characterized by pain, swelling, snapping, locking, knee instability and limited mobility [1, 10], is mainly diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and treated by arthroscopic surgery [11]. Although the overall postoperative clinical outcomes of symptomatic DLM are acceptable [12–14], the outcomes still differ among individuals, possibly as a result of the diversity in patient characteristics and treatments [11]. Recently studies have reported several factors that influence postoperative effect in symptomatic DLM, but the sample sizes used in these studies are uneven, and the results are inconsistent [12, 15–17]. The present research independently analyses 14 possible influences, including gender, body mass index (BMI), and other factors, in a larger series of patients with the goal of identifying the factors that influence postoperative outcome in patients with symptomatic DLM and thereby guiding clinical application.

Methods

Subjects

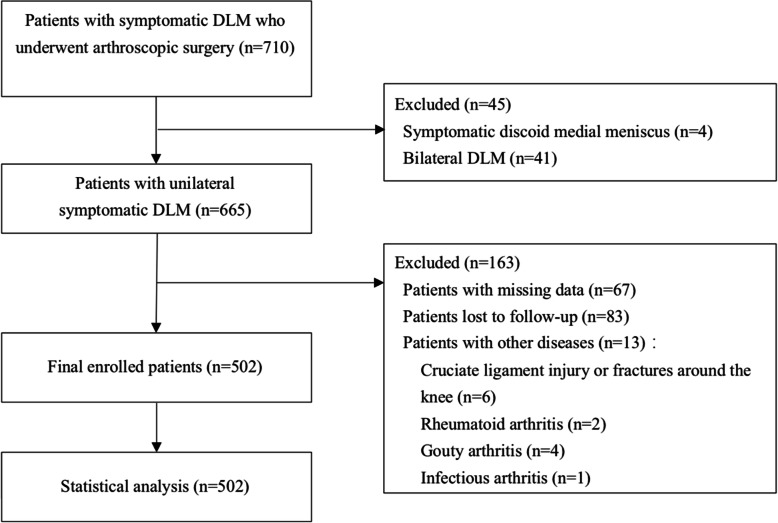

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution. The inclusion criteria were as follows: DLM patients with symptoms (pain, swelling, snapping, locking, knee instability and limited mobility) who underwent arthroscopic surgery at the Sports Medicine Center of West China Hospital of Sichuan University from September 2008 to September 2015. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with missing data; patients lost to follow-up; patients with bilateral symptomatic DLM who underwent bilateral knee operation; patients with symptomatic discoid medial meniscus, knee ligament injury or knee fracture; patients with rheumatoid arthritis or gouty arthritis of the knee; and patients with knee infections. A flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study

Research methods

The following 14 independently factors that might possibly affect the postoperative results of patients with symptomatic DLM were collected from the patients’ medical records, imaging data and arthroscopy videos: sex; BMI (kg/m2); work intensity (based on‘REFA daily life and work intensity classification’ [18], schedule 1); trauma history (clinical symptoms of knee joints due to sports, sprains, falls, etc.); involved knee joint (left or right); age of onset; duration of symptoms; DLM type according to the Watanabe Classification [17], schedule 2; type of DLM tear (based on the O’Connor classification of meniscus tears [19], schedule 3); medial meniscus tear; severity of cartilage lesion classified according to Outerbridge grade [20], schedule 4; Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis grade [21] (K-L grade, schedule 5); method of surgery (saucerization, saucerization with repair, total meniscectomy); and final follow-up time. The intraarticular factors listed above, liking DLM type, Outerbridge grade, etc. were evaluated by arthroscopy. The choice of surgical mode depends primarily on the condition of the DLM. If the circular fibres of the DLM are continuous, saucerization is used; if they are discontinuous, total meniscectomy is conducted; if the DLM is continuous and accompanied by instability or tear of a peripheral rim or a repairable tear in the red zone, saucerization with repair is performed. All of the surgical procedures for all patients were performed by the same senior surgeon, whose surgical technique was reliable and stable. Preoperative and postoperative knee function were evaluated using the IKDC subjective knee evaluation form [22] (schedule 6). The score was obtained through periodic outpatient follow-up. In the overall scores of IKDC, scores of 90–100, 80–89, 70–79 and < 70 points were categorized as “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” and “poor,” respectively [22]. Given the clinical application, we combined fair and poor into one level (fair-poor) representing an unsatisfactory postoperative effect. The basic characteristics of the included subjects are shown in Table 1. The assignment of categorical variables and the IKDC classification are shown in Table 2. The factors affecting the postoperative outcomes of symptomatic DLM were explored by analysing the correlation between the above 14 factors and IKDC classification.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included patients

| Demographic details | N (%)/M (range; IQR) † | Demographic details | N (%)/M (range; IQR) † | Demographic details | N (%)/M (range; IQR) † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 502 | ≤14 | 88(17.5%) | Yes | 18 (3.6%) |

| Sex | 14–25 | 101(20.1%) | Outerbridge grade | ||

| Male | 149 (29.7%) | 25–45 | 202(40.2%) | No lesion | 358 (71.3%) |

| Female | 353 (70.3%) | ≥45 | 111(22.1%) | Grade I | 29 (5.8%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.0 (range, 13.8 ~ 44.4; 4.3) | Symptoms duration (months) | 10.0 (range, 0.05 ~ 246; 21.0) | Grade II | 52 (10.4%) |

| < 18.5 | 54(10.8%) | ≤1 | 64(12.7%) | Grade III | 23 (4.6%) |

| 18.5–25 | 362(72.1%) | 1–6 | 149(29.7%) | Grade IV | 40 (8.0%) |

| ≥25 | 86(17.1%) | 6–24 | 184(36.7%) | K-L grade | |

| Work intensity | >24 | 105(20.9%) | Grade 0 | 375 (74.7%) | |

| Grade 0 | 27 (5.6%) | Watanabe type | Grade I | 56 (11.2%) | |

| Grade 1 | 212 (42.2%) | Complete | 423 (84.3%) | Grade II | 44 (8.8%) |

| Grade 2 | 240 (47.8%) | Incomplete | 79 (15.7%) | Grade III | 23 (4.6%) |

| Grade 3 | 22 (4.4%) | O’Connor type | Grade IV | 4 (0.8%) | |

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.2%) | No tear | 38 (7.6%) | Type of surgery | |

| Trauma history | Longitudinal (/bucket handle) tear | 171 (34.1%) | Saucerization | 410 (81.7%) | |

| No | 360 (71.7%) | Horizontal tear | 154 (30.7%) | Saucerization with repair | 16 (3.2%) |

| Yes | 142 (28.3%) | Oblique tear | 10 (2.0%) | Ttotal meniscectomy | 76 (15.1%) |

| Involved knee joint | Transverse (/radial) tear | 45 (9.0%) | Follow-up time (months) | 75.4 (range, 41.0 ~ 123.3; 33.7) | |

| Left | 252 (50.2%) | Variant tear | 84 (16.7%) | ≤60 | 135(26.9%) |

| Right | 250 (49.8%) | Medial meniscus tear | 60–96 | 254(50.6%) | |

| Age of onset (years) | 32.0 (range, 3 ~ 80; 26.3) | No | 484 (96.4%) | >96 | 113(22.5%) |

BMI body mass index, K-L grade Kellgren–Lawrence grade, DLM discoid lateral meniscus, IKDC International Knee Documentation Committee, † N number, M median, IQR interquartile range

Table 2.

Assignment of research factors and IKDC classification

| Factors/IKDC classification | Valuation |

|---|---|

| Sex (X1) | male “0”; female “1” |

| BMI (kg/m2) (X2) | X2 < 18.5 “1”; 18.5 ≤ X2 < 25 “2”; X2 ≥ 25 “3” |

| Work intensity (X3) | grade 0 ~ 1 “1”; grade 2 “2”; grade 3 ~ 4 “3” |

| History of trauma (X4) | no “0”; yes “1” |

| Involved knee joint (X5) | left knee “0”; right knee “1” |

| Age of onset (year) (X6) | X6 ≤ 14 “1”; 14 < X6< 25 “2”; 25 ≤ X6 < 45 “3”; X6 ≥ 45 “4” |

| Symptom duration (month) (X7) | X7 ≤ 1 “1”; 1 < X7 ≤ 6 “2”; 6 < X7 ≤ 24 “3”; X7 > 24 “4” |

| Watanabe type (X8) | type I (complete) “1”; type II (incomplete) “2” |

| O’Connor type (X9) | no “0”; longitudinal (/bucket handle) tear “1”; horizontal tear “2”; oblique tear “3”; transverse (/radiation) tear “4”; variant tear (including flap, composite, degenerate meniscus tear) “5” |

| Medial meniscus tear (X10) | no “0”; yes “1” |

| Outerbridge grade (X11) | no “0”; grade I “1”; grade II “2”; grade III ~ IV “3” |

| K-L grade (X12) | grade 0 “0”; grade I “1”; grade II “2”; grade III ~ IV “3” |

| Type of surgery (X13) | Saucerization “1”; Saucerization with repair “2”; Total meniscectomy “3” |

| Follow-up time (month)(X14) | X14 ≤ 60 “1”; 60 < X14 ≤ 96; X14 > 96 |

| IKDC classification (Y) | < 70 (poor) ~ 70–79 (fair) “1”; 80–89 (good) “2”; ≥90 (excellent) “3” |

BMI body mass index, K-L grade Kellgren–Lawrence grade, DLM discoid lateral meniscus, IKDC International Knee Documentation Committee

Statistical method

The data were statistically analysed using SPSS 25.0. A normality test revealed that the measurement data were not normally distributed. The measurement data and enumeration data are described by the median (M) and interquartile range (IQR) and by the number of cases (percentage), respectively. The differences between the preoperative and postoperative knee function scores were analysed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. In the univariate analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskall-Wallis rank sum test were used to analyse the differences in rank data between two groups and among multiple groups, severally. The model meets the parallelism through parallel test, and multivariate analysis was conducted using the ordinal logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of the subjects

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 502 patients were eventually included in our study, including 353 females (70.3%) and 149 males (29.7%), 252 (50.2%) left knees and 250 (49.8%) right knees. The median age of onset and the median duration of symptoms were 32.0 years (range, 3 ~ 80 years; IQR, 26.3) and 10.0 months (range, 0.05 ~ 246 months; IQR, 21.0), respectively. Other baseline information on the patients is shown in Table 1. The median postoperative IKDC score of (87.4; range, 41.4 ~ 97.7; IQR, 14.6) was higher than the median preoperative score (57.6; range, 26.9 ~ 64.9; IQR, 9.7) (P < 0.001). (Table 3). In the follow-up, none of the patients required reoperation or experienced complications after surgery.

Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative IKDC score

| Preoperative M (IQR)/N (%) † |

Postoperative M (IQR)/N (%) † |

Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC score | 57.6 (9.7) | 87.4 (14.6) | −19.420 | 0.000* |

| < 70 (poor) | 502 (100.0%) | 55 (11.0%) | ||

| 70 ~ 79 (fair) | 0(0.0%) | 84 (16.7%) | ||

| 80 ~ 89 (good) | 0(0.0%) | 164 (32.7%) | ||

| ≥ 90 (excellent) | 0(0.0%) | 199 (39.6%) |

IKDC International Knee Documentation Committee, † M median, IQR interquartile range, † N number

*Statistically significant (P < .05)

Univariate analysis of the correlation between the investigated factors and IKDC classification

Factors such as sex, BMI, work intensity, trauma history, age of onset, symptoms duration, medial meniscus tear, Outerbridge grade, K-L grade and type of surgery were associated with the IKDC classification (P < 0.05). Involved knee joint (left or right), Watanabe type, O’Connor tear type and follow-up time did not correlate with the IKDC classification (P > 0.05). Table 4.

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of the correlation between the research factors and IKDC classification

| Variable | IKDC grade | Z/kruskall-wallis χ2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair and poor N (%) † |

Good N (%) † |

Excellent N (%) † |

|||

| Sex | −4.362 | 0.000* | |||

| Female | 114(32.3) | 119(33.7) | 120(34.0) | ||

| male | 25(16.8) | 45(30.2) | 79(53.0) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 66.642 | 0.000* | |||

| < 18.5 | 7(13.0) | 4(7.4) | 43(79.6) | ||

| 18.5 ~ 25 | 86(23.8) | 129(35.6) | 147(40.6) | ||

| ≥ 25 | 46(53.5) | 31(36.0) | 9(10.5) | ||

| Work intensity | 74.092 | 0.000* | |||

| Grade 0 ~ 1 | 39(16.3) | 56(23.4) | 144(60.3) | ||

| Grade 2 | 90(37.5) | 98(40.8) | 52(21.7) | ||

| Grade 3 ~ 4 | 10(43.5) | 10(43.5) | 3(13.0) | ||

| History of trauma | −2.618 | 0.009* | |||

| No | 113(31.4) | 113(31.4) | 134(37.2) | ||

| Yes | 26(18.3) | 51(35.9) | 65(45.8) | ||

| Involved knee joint | −0.843 | 0.399 | |||

| Left | 65(25.8) | 84(33.3) | 103(40.9) | ||

| Right | 74(29.6) | 80(32.0) | 96(38.4) | ||

| Age of onset (year) | 188.575 | 0.000* | |||

| ≤ 14 | 2(2.3) | 11(12.5) | 75(85.2) | ||

| 14 ~ 25 | 9(8.9) | 22(21.8) | 70(69.3) | ||

| 25 ~ 45 | 62(30.7) | 94(46.5) | 46(22.8) | ||

| ≥ 45 | 66(59.5) | 37(33.3) | 8(7.2) | ||

| Symptoms duration (month) | 26.939 | 0.000* | |||

| ≤ 1 | 13(20.3) | 21(32.8) | 30(46.9) | ||

| 1 ~ 6 | 34(22.8) | 52(34.9) | 63(42.3) | ||

| 6 ~ 24 | 43(23.4) | 58(31.5) | 83(45.1) | ||

| >24 | 49(46.7) | 33(31.4) | 23(21.9) | ||

| Watanabe type | −1.867 | 0.062 | |||

| Complete | 111(26.2) | 138(32.6) | 174(41.1) | ||

| Incomplete | 28(35.4) | 26(32.9) | 25(31.6) | ||

| O’Connor tear type | 8.129 | 0.149 | |||

| No tearing | 12(31.6) | 11(28.9) | 15(39.5) | ||

| Longitudinal (/bucket handle) tear | 50(29.2) | 51(29.8) | 70(40.9) | ||

| Horizontal tear | 31(20.1) | 53(34.4) | 70(45.5) | ||

| Oblique tear | 3(30.0) | 4(40.0) | 3(30.0) | ||

| Transverse (/radial) tear | 15(33.3) | 14(31.1) | 16(35.6) | ||

| Variant tear | 28(33.3) | 31(36.9) | 25(29.8) | ||

| Medial meniscus tear | −2.876 | 0.004* | |||

| No | 127(26.2) | 162(33.5) | 195(40.3) | ||

| Yes | 12(66.7) | 2(11.1) | 4(22.2) | ||

| Outerbridge grade | 116.370 | 0.000* | |||

| No injury | 51(14.2) | 129(36.0) | 178(49.7) | ||

| Grade I | 11(37.9) | 6(20.7) | 12(41.4) | ||

| Grade II | 29(55.8) | 18(34.6) | 5(9.6) | ||

| Grade III ~ IV | 48(76.2) | 11(17.5) | 4(6.3) | ||

| K-L grade | 116.570 | 0.000* | |||

| Grade 0 | 57(15.2) | 133(35.5) | 185(49.3) | ||

| Grade I | 26(46.4) | 19(33.9) | 11(19.6) | ||

| Grade II | 34(77.3) | 9(20.5) | 1(2.3) | ||

| Grade III ~ IV | 22(81.5) | 3(11.1) | 2(7.4) | ||

| Follow-up time (month) | 5.542 | 0.063 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 47(34.8) | 44(32.6) | 44(32.6) | ||

| 60–96 | 65(25.6) | 81(31.9) | 108(42.5) | ||

| >96 | 27(23.9) | 39(34.5) | 47(41.6) | ||

| Type of surgery | 77.186 | 0.000* | |||

| Saucerization | 80(19.5) | 142(34.6) | 188(45.9) | ||

| Saucerization with repair | 5(31.3) | 5(31.3) | 6(37.5) | ||

| Total meniscectomy | 54(71.1) | 17(22.4) | 5(6.6) | ||

IKDC International Knee Documentation Committee, BMI body mass index, K-L grade Kellgren–Lawrence grade, †N number

*Statistically significant (P < .05)

Multivariate analysis of the correlation between the investigated factors and IKDC classification

Male sex was associated with higher IKDC score (P = 0.023, odds ratio (OR) = 1.702, 95% confidence interval (CI):1.076–2.697). Compared with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 was associated with better IKDC score (P = 0.026, OR = 3.016, 95% CI: 1.138–7.996), while no difference was found between 18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 regarding IKDC score (P = 0.063, OR = 1.701, 95% CI: 0.972–2.974). In contrast to age of onset ≥45 years, ≤14 years (P = 0.000, OR = 20.780, 95% CI: 7.822–55.147) and 14 ~ 25 years (P = 0.000, OR = 8.516, 95% CI: 3.755–19.317) were predictive of obtaining a good IKDC score, whereas there was no significant difference between the IKDC score of 25 ~ 45 years and ≥ 45 years (P = 0.098, OR = 1.725, 95% CI: 0.904–3.294). In comparison with symptoms duration> 24 months, the odds of better postoperative IKDC score for symptoms duration ≤1 month (P = 0.001, OR = 3.511, 95% CI: 1.699–7.265), 1 ~ 6 months (P < 0.001, OR = 3.463; 95% CI: 1.914–6.265) and 6 ~ 24 months (P < 0.001, OR = 3.254; 95% CI: 1.855–5.703) were significantly elevated. Compared to the Outerbridge grade III ~ IV, no injury (P < 0.001, OR = 6.379; 95% CI:2.545–15.975) and Outerbridge grade I (P = 0.01, OR = 4.332; 95% CI:1.142–13.277) were favourable factors for acquiring higher IKDC score, while no difference was found between grade II and grade III ~ IV in terms of IKDC score (P = 0.12, OR = 2.134; 95% CI:0.820–5.551). Work intensity, history of trauma, medial meniscus tear, K-L grade and type of surgery were not significant predictors of IKDC score (P > 0.05 for all). (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of the correlation between research factors and IKDC classification

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 0.532 | 0.234 | 5.151 | 0.023* | 1.702 | 1.076 | 2.697 |

| Female‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| < 18.5 | 1.104 | 0.497 | 4.926 | 0.026* | 3.016 | 1.138 | 7.996 |

| 18.5 ~ 25 | 0.531 | 0.285 | 3.467 | 0.063 | 1.701 | 0.972 | 2.974 |

| ≥ 25‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Work intensity | |||||||

| Grade 0 ~ 1 | 0.331 | 0.506 | 0.427 | 0.514 | 1.392 | 0.516 | 3.751 |

| Grade 2 | −0.223 | 0.481 | 0.214 | 0.644 | 0.800 | 0.312 | 2.056 |

| Grade 3 ~ 4‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| History of trauma | |||||||

| No | −0.179 | 0.232 | 0.597 | 0.440 | 0.836 | 0.531 | 1.317 |

| Yes‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Age of onset (year) | |||||||

| ≤ 14 | 3.034 | 0.498 | 37.069 | 0.000* | 20.780 | 7.822 | 55.147 |

| 14 ~ 25 | 2.142 | 0.418 | 26.293 | 0.000* | 8.516 | 3.755 | 19.317 |

| 25 ~ 45 | 0.545 | 0.33 | 2.732 | 0.098 | 1.725 | 0.904 | 3.294 |

| ≥ 45‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Symptoms duration (month) | |||||||

| ≤ 1 | 1.256 | 0.37 | 11.501 | 0.001* | 3.511 | 1.699 | 7.265 |

| 1 ~ 6 | 1.242 | 0.303 | 16.826 | 0.000* | 3.463 | 1.914 | 6.265 |

| 6 ~ 24 | 1.180 | 0.287 | 16.949 | 0.000* | 3.254 | 1.855 | 5.703 |

| >24‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Medial meniscus tear | |||||||

| No | 0.089 | 0.624 | 0.021 | 0.886 | 1.093 | 0.322 | 3.717 |

| Yes‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Outerbridge grade | |||||||

| No injury | 1.853 | 0.469 | 15.629 | 0.000* | 6.379 | 2.545 | 15.975 |

| Grade I | 1.466 | 0.572 | 6.569 | 0.010* | 4.332 | 1.412 | 13.277 |

| Grade II | 0.758 | 0.488 | 2.418 | 0.120 | 2.134 | 0.820 | 5.551 |

| Grade III ~ IV‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| K-L grade | |||||||

| Grade 0 | 0.184 | 0.690 | 0.071 | 0.790 | 1.202 | 0.311 | 4.646 |

| Grade I | −0.112 | 0.685 | 0.027 | 0.870 | 0.894 | 0.233 | 3.425 |

| Grade II | −0.563 | 0.707 | 0.634 | 0.426 | 0.569 | 0.142 | 2.277 |

| Grade III ~ IV‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

| Type of surgery | |||||||

| Saucerization | 0.546 | 0.387 | 1.983 | 0.159 | 1.726 | 0.807 | 3.688 |

| Saucerization with repair | −0.262 | 0.678 | 0.149 | 0.699 | 0.770 | 0.204 | 2.907 |

| Total meniscectomy‡ | – | – | – | – | 1.000 | – | – |

IKDC International Knee Documentation Committee, BMI body mass index, K-L grade Kellgren–Lawrence grade

‡ represent reference group; *Statistically significant (P < .05)

Discussion

IKDC score, a subjective method of evaluating knee function, not only focuses on the evaluation of the patient’s symptoms and the stability of the knee joint, but also attaches importance to the assessment of knee motor function and is widely used because it allows accurate and comprehensive evaluation of knee function. After analyzing the correlation of 14 independent factors with postoperative IKDC classification, we found that sex, BMI, age of onset, symptoms duration and cartilage injury and its degree affect postoperative IKDC classification, while preoperative work intensity, DLM type, DLM tear and its O’Connor type, combined medial meniscus injury, K-L grade, postoperative follow-up time and type of surgery did not significantly affect the postoperative result.

Male sex is a favourable factor in many orthopaedic diseases, but its correlation with postoperative efficacy in patients with DLM is controversial. Ahn [23] et al. demonstrated that male sex was conducive to good postoperative outcomes by evaluating 260 patients with DLM. Through investigating 502 patients with DLM, we also found that male sex was a protective factor for good knee function (P = 0.023, OR = 1.702, 95% CI: 1.076–2.697). Compared with males, on one hand, females have increased rates of cartilage loss and progression of cartilage defects at the knee [24]. On the other hand, the knee articular cartilage volume is smaller and the Q angle is greater in females [13, 25, 26]. Thus, females are more susceptible to cartilage lesions and osteoarthritis [24] and being female is associated with poor postoperative clinical outcomes. However, Chen et al. [12] and Kose et al. [17] found that sex has no significant effect on postoperative result of DLM; this finding may be related to the small sample size in their study (n = 39 cases, n = 48 cases, respectively).

For symptomatic DLM, numerous studies have found that the earlier the age of onset is, the shorter is the duration of symptoms (especially < 12 months) and that the earlier the surgical intervention is performed, the better is the prognosis [11, 12, 14, 23, 27]. We found that the age of onset < 25 years, especially < 14 years (P < 0.001, OR = 37.069; 95% CI: 7.822–55.147), and the symptoms duration < 24 months (P < 0.001, OR = 3.254; 95% CI: 1.855–5.703) are advantageous for postoperative efficacy. It has been reported that the younger age of onset and a shorter course of the disease are correlated with a lower risk of articular chondromalacia and damage caused by DLM lesions [11, 13, 28]. Moreover, early normalization of DLM morphology by surgery not only increases the mobility of the meniscus, but also enhances the adaptability of the meniscus to the tibiofemoral surface, thereby reducing damage and degeneration of the meniscus and articular cartilage arising from excessive stress concentration [11, 14, 29]. In addition, shaping DLM in childhood may improve the dysplasia of the femoral condyle and the abnormality of the lower limb alignment, thus abating the risk of cartilage degeneration and delaying the occurrence and development of osteoarthritis [16, 30, 31].

This study found that BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 is associated with a higher likelihood of obtaining better postoperative results (P = 0.026, OR = 3.016; 95% CI: 1.138–7.996). Fu [13] et al. found that patients with BMI > 23.0 kg/m2 were more likely to suffer from articular cartilage lesions. High BMI has been shown to be the main risk factor for knee osteoarthritis, as obesity can lead to excessive compression of the meniscus and to loss of and pathological changes in the articular cartilage [32–34]. Hence, lower BMI is related to lower occurrence of articular cartilage lesions and knee osteoarthritis and thus better postoperative efficacy. Nonetheless, we found no effect of work intensity on the postoperative outcomes of symptomatic DLM (P > 0.05); this may be because that work intensity is more reflects the activity of entire body rather than the pressure on the meniscus and cartilage of the knee.

The results of this study indicate that the absence of articular cartilage lesions (P < 0.001, OR = 6.379; 95% CI:2.545–15.975) and Outerbridge grade I (P = 0.001, OR = 4.322; 95% CI: 1.412–13.277) are beneficial factors for postoperative recovery of knee function. Outerbridge grade ≥ II is an unfavourable factor for postoperative outcome (P = 0.12, OR = 2.134). The clinical manifestations of an articular cartilage lesion may not be obvious in the short term, but most patients will eventually have knee degeneration associated with cartilage damage, which leads to irreversible severe osteoarthritis drastically affecting knee function [35]. Hiroshi et al. [36] consider that the Outerbridge grade can directly reflects the severity of the cartilage lesions and is the decisive factor affecting the long-term outcomes after meniscal surgery. Although K-L grade is an imaging index that is used to assess the severity of degeneration of the knee, we observed no relationship between KL grade and postoperative outcome, probably because X-rays are less sensitive in visualizing cartilage lesions [37] and because early joint space reduction is secondary not to articular cartilage thinning but to meniscal compression [14]. Moreover, Kose et al. [17] have shown that the combined medial meniscus tears did not affect postoperative outcomes, which is similar to the result of our study.

Generally, surgical methods for the arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic DLM by arthroscope includes saucerization (partial meniscectomy), saucerization with repair and total meniscectomy [27, 28, 38–40]. At present, the effect of surgical mode on postoperative outcomes is disputable. Ahn et al. [41] considered that partial meniscectomy with repair has a good efficacy in children with symptomatic DLM compared with total meniscectomy; this may be because partial meniscectomy with repair can prevent early degenerative changes of the joint [2]. However, Lee et al. [11] harbour the opposite opinion that residual discoid meniscus tissue is prone to degeneration and re-injury due to its abnormally fibrous structure, which may lead to adverse clinical effects. Considering the high cost and uncertain effectiveness of repair, repair of the abnormal anatomy in a torn DLM is not recommended [42]. Some scholars have not found the differences in clinical outcomes between partial meniscectomy and total meniscectomy in the short or medium term, but the clinical efficacy of partial meniscectomy is better than that of total meniscectomy in the long-term follow-up [28, 31, 38–40, 42–44]. Conversely, Ikeuchi et al. [5] reported that the results of partial meniscectomy were significantly worse than those of total meniscectomy. However, Lee et al. [45] and Wong and Wang [27] concluded that there was no significant difference among these three surgical methods in postoperative outcomes. In addition, a systematic review did not find a difference in postoperative outcome between partial meniscectomy with repair and saucerization, but these two methods have significantly improved outcomes over total meniscectomy [42]. In the present study, we discovered that the type of surgery does not affect the postoperative result. The discrepancies in the results obtained in these studies may exist because the choice of surgical method was affected by factors such as age at surgery, location of DLM tear, severity of the DLM tear and other factors and because the number of patients who underwent saucerization with repair and total meniscectomy were small.

Similar to the results of other studies [11, 12, 17], we also found that DLM type has no significant effect on postoperative efficacy. This may be why no significant differences were found in the incidence of articular cartilage lesions and postoperative discoid meniscus morphology among different types of discoid meniscus [13, 29, 46].

Regarding DLM tear, some studies reported that DLM tears could lead to degeneration of the articular cartilage and osteoarthritis in the long term [29, 47], thus contributing to poor postoperative outcomes. However, Ding et al. [29] and Kose et al. [17] concluded that discoid meniscus injuries are not correlated with articular cartilage lesions. In our study, DLM tears did not affect the postoperative effect, and no difference in cartilage damage was observed during arthroscopy with respect to whether or not DLM tear exist; this may be because that the majority of our patients with DLM tears had obvious symptoms and received timely diagnosis and treatment.

Concerning the influence of O’Connor tear type on the postoperative result, Chen et al. [12] and Badlani et al. [48] considered that radial tears lead to poor postoperative outcomes. Ahn et al. [28] found that compared with other tear types, the duration of symptoms of horizontal meniscus tear, as a degenerative tear, is longer and the postoperative residual meniscus tissue is reduced and fragile, which may accelerate the radiological progression of postoperative KL grade 3/4 osteoarthritis. However, other studies observed that the duration of symptoms in cases of horizontal tear may not be significantly different from that in cases with other tear types [2, 49]. Here, we did not find a correlation of O’Connor tear type with postoperative effect; this may be attributed to the fact that the severity of cartilage damage is not related to the type of DLM tear [13] as well as to the fact that the difference in thickness between DLM and normal meniscus is not obvious even though removing a layer of horizontal meniscus tear as the discoid meniscus is thicker than the normal meniscus.

Longer follow-up is believed to be associated with more severe articular cartilage degeneration and clinical symptoms and worse knee joint function [11, 44]. In our study, the median follow-up time was 75.4 (range, 41 ~ 123; IQR, 33.7) months, and the final follow-up time was not correlated with postoperative efficacy of symptomatic DLM; this may be due to the small number of patients with follow-up time over 120 months.

We acknowledge that our study has some limitations. At the final follow-up, the assessment of postoperative efficacy didn’t analyse the imaging changes but only evaluated the subjective functional parameters; thus, there was no objective evaluation index that corresponded to the postoperative outcome. Moreover, this study is only a retrospective multivariate analysis, and the conclusions obtained should be further confirmed by prospective studies.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic DLM is safe and effective, but its clinical efficacy is affected by many factors. Specifically, male sex, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, age of onset < 25 years (especially < 14 years) and symptoms duration < 24 months are conducive to good postoperative outcomes. Combined articular cartilage injury (Outerbridge grade ≥ 2) is more likely to lead to poor postoperative effect. However, complicating medial meniscus injury, K-L grade, preoperative work intensity, DLM type, DLM tear and its O’Connor type, type of surgery, and postoperative follow-up time did not significantly affect the postoperative result.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patient shown in the article.

Abbreviations

- DLM

Discoid lateral meniscus

- BMI

Body mass index

- IKDC

International Knee Documentation Committee

- K-L

Kellgren-Lawrence

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- M

Median

- OR

Odds ratio

- IQR

Interquartile range

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

S.J. Yang and Z.J. Ding participated in the surgery, collected clinical data, and made major contributions to writing and editing of the manuscript. Y. Xue initiated the work and collected clinical data. J. Li performed surgery and was responsible for the screening of the patients and for postoperative follow-up. G. Chen participated in the entire process, including surgery, follow-up of the patients, data collection, and writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Department (No. 2017SZ0017, No. 2018FZ0040).

Availability of data and materials

The patient’s personal information and imaging data obtained at following-up were stored on disc. The data are available from the corresponding author upon request. G. Chen should be contacted with requests for data and materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human and Ethics Committee for Medical Research at Sichuan University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Ethical Committee Approval: Version number 1.1, 26 October 2016). Written medical informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their participation in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the publication of the article. The patient and his family have provided written consent to be publication and disclosure of the patient’s clinical data.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kocher MS, Logan CA, Kramer DE. Discoid lateral meniscus in children: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:736–743. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masquijo JJ, Bernocco F, Porta J. Discoid meniscus in children and adolescents: correlation between morphology and meniscal tears. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.recot.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadopoulos A, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Histomorphologic study of discoid meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuta S, Masaki K, Korai F. Prevalence of abnormal findings in magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic knees. J Orthop. 2002;7:287–291. doi: 10.1007/s007760200049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeuchi H. Arthroscopic treatment of the discoid lateral meniscus. Technique and long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982:19–28. [PubMed]

- 6.Kim SJ, Lee YT, Kim DW. Intraarticular anatomic variants associated with discoid meniscus in Koreans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:202–207. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao PS, Rao SK, Paul R. Clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic assessment of discoid lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:275–277. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.19973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Jiang Q. Review of discoid meniscus. Orthop Surg. 2011;3:219–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-7861.2011.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SH. Editorial commentary: why should the contralateral side be examined in patients with symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus? Arthroscopy. 2019;35:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LX, Ao YF, Yu JK, Miao Y, Leung KK, Wang HJ, Lin L. Clinical features and prognosis of discoid medial meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:398–402. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1979-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CR, Bin SI, Kim JM, Lee BS, Kim NK. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in young patients with symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus: an average 10-year follow-up study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138:369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2853-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H-C, Yang C-B, Tsai C-F, Ma H-L, Liu C-L, Huang T-F. Management and outcome of discoid meniscus tears. Formosan J Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;2:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu D, Guo L, Yang L, Chen G, Duan X. Discoid lateral meniscus tears and concomitant articular cartilage lesions in the knee. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persiani P, Mariani M, Crostelli M, Mascello D, Mazza O, Ranaldi FM, Martini L, Villani C. Can early diagnosis and partial meniscectomy improve quality of life in patients with lateral discoid meniscus? Clin Ter. 2013;164:e359–e364. doi: 10.7417/CT.2013.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G, Zhang Z, Li J. Symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus: a clinical and arthroscopic study in a Chinese population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:329. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1188-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habata T, Uematsu K, Kasanami R, Hattori K, Takakura Y, Tohma Y, Fujisawa Y. Long-term clinical and radiographic follow-up of total resection for discoid lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1339–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kose O, Celiktas M, OF E, Guler F, Ozyurek S, Sarpel Y. Prognostic factors affecting the outcome of arthroscopic saucerization in discoid lateral meniscus: a retrospective analysis of 48 cases. Musculoskelet Surg. 2015;99:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s12306-015-0376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus TM, Abele C, Freude T, Ateschrang A, Stockle U, Stuby FM, Schroter S. Duration of incapacity of work after tibial plateau fracture is affected by work intensity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:281. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahriaree H. O’Conner’s textbook of arthroscopic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Gomez-Cardero P. The outerbridge classification predicts the need for patellar resurfacing in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1254–1257. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1123-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiphof D, Boers M, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Differences in descriptions of Kellgren and Lawrence grades of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1034–1036. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:226–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01560215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn JY, Kim TH, Jung BS, Ha SH, Lee BS, Chung JW, Kim JM, Bin SI. Clinical results and prognostic factors of arthroscopic surgeries for discoid lateral menisci tear: analysis of 179 cases with minimum 2 years follow-up. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24:108–112. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2012.24.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna FS, Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, Wang Y, Urquhart DM, English DR, Giles GG, Cicuttini FM. Women have increased rates of cartilage loss and progression of cartilage defects at the knee than men: a gender study of adults without clinical knee osteoarthritis. Menopause. 2009;16:666–670. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318198e30e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho HJ, Chang CB, Yoo JH, Kim SJ, Kim TK. Gender differences in the correlation between symptom and radiographic severity in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1749–1758. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1282-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicuttini F, Forbes A, Morris K, Darling S, Bailey M, Stuckey S. Gender differences in knee cartilage volume as measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1999;7:265–271. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong T, Wang CJ. Functional analysis on the treatment of torn discoid lateral meniscus. Knee. 2011;18:369–372. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn JH, Kang DM, Choi KJ. Risk factors for radiographic progression of osteoarthritis after partial meniscectomy of discoid lateral meniscus tear. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding J, Zhao J, He Y, Huangfu X, Zeng B. Risk factors for articular cartilage lesions in symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:1423–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SJ, Bae JH, Lim HC. Does torn discoid meniscus have effects on limb alignment and arthritic change in middle-aged patients? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:2008–2014. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P, Zhao Q, Shang X, Wang Y. Effect of arthroscopic resection for discoid lateral meniscus on the axial alignment of the lower limb. Int Orthop. 2018;42:1897–1903. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3944-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Englund M, Felson DT, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Wang K, Crema MD, Lynch JA, Sharma L, Segal NA, Lewis CE, Nevitt MC. Risk factors for medial meniscal pathology on knee MRI in older US adults: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1733–1739. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulkarni K, Karssiens T, Kumar V, Pandit H. Obesity and osteoarthritis. Maturitas. 2016;89:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sowers MR, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA. The evolving role of obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:533–537. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833b4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steadman JR, Rodkey WG, Rodrigo JJ. Microfracture: surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:S362–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Higuchi H, Kimura M, Shirakura K, Terauchi M, Takagishi K. Factors affecting long-term results after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Amin S, LaValley MP, Guermazi A, Grigoryan M, Hunter DJ, Clancy M, Niu J, Gale DR, Felson DT. The relationship between cartilage loss on magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic progression in men and women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3152–3159. doi: 10.1002/art.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bin SI, Jeong SI, Kim JM, Shon HC. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for horizontal tear of discoid lateral meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10:20–24. doi: 10.1007/s001670100241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SJ, Chun YM, Jeong JH, Ryu SW, Oh KS, Lubis AM. Effects of arthroscopic meniscectomy on the long-term prognosis for the discoid lateral meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1315–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0391-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stilli S, Marchesini Reggiani L, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Cappella M, Donzelli O. Arthroscopic treatment for symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus during childhood. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahn JH, Lee SH, Yoo JC, Lee YS, Ha HC. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy with repair of the peripheral tear for symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus in children: results of minimum 2 years of follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smuin DM, Swenson RD, Dhawan A. Saucerization versus complete resection of a symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus at short- and long-term follow-up: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1733–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn JH, Kim KI, Wang JH, Jeon JW, Cho YC, Lee SH. Long-term results of arthroscopic reshaping for symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus in children. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee YS, Teo SH, Ahn JH, Lee OS, Lee SH, Lee JH. Systematic review of the long-term surgical outcomes of discoid lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1884–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee DH, D'Lima DD, Lee SH. Clinical and radiographic results of partial versus total meniscectomy in patients with symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atay OA, Doral MN, Leblebicioglu G, Tetik O, Aydingoz U. Management of discoid lateral meniscus tears: observations in 34 knees. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:346–352. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Shang XK, Mao BN, Li J, Chen G. Torn discoid lateral meniscus is associated with increased medial meniscal extrusion and worse articular cartilage status in older patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:2624–2631. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badlani JT, Borrero C, Golla S, Harner CD, Irrgang JJ. The effects of meniscus injury on the development of knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1238–1244. doi: 10.1177/0363546513490276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahrezaee M, Maheronnaghsh R, Hashemitaheri A, Chavoshi M. Proximal Tibiofibular joint inclination angle and associated meniscal tear in patients with discoid lateral meniscus. Maedica. 2019;14:116–120. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2019.14.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The patient’s personal information and imaging data obtained at following-up were stored on disc. The data are available from the corresponding author upon request. G. Chen should be contacted with requests for data and materials.