Abstract

Although the cell surfaceome is predominantly targeted and drugged with antibodies, its pocketome fraction is only accessible to small molecules and constitutes a rich subset of binding sites with immense potential diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Compared to antibodies, however, small molecules are disadvantaged by their less confined biodistribution, shorter circulatory half-life, and inability to communicate with the immune system. Presented herein is a method that endows small molecules with the ability to recruit and activate chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts). It is based on a CAR-T platform that uses a chemically programmed antibody fragment (cp-Fab) as on/off switch. In proof-of-concept studies, this cp-Fab/CAR-T system targeting folate binding sites in the cell surfaceome mediated potent and specific eradication of folate receptor-expressing cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. The method harnesses an increasing quantity and quality of cell surfaceome-targeting small molecules derived from virtual and actual small molecule libraries.

Keywords: CAR-T, catalytic antibody, cell surfaceome, chemical programming, pocketome

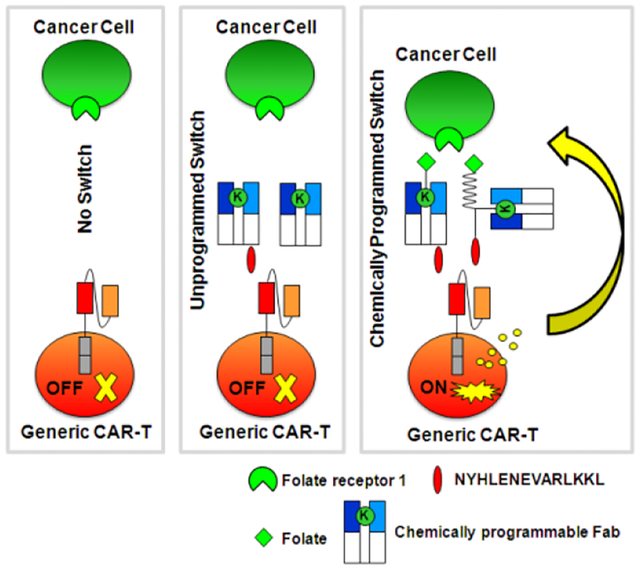

Graphical Abstract

A novel small molecule-controlled CAR-T therapy was developed based on a chemically programmed Fab as an on/off switch. For proof-of-concept, a folate-programmed Fab switch mediated potent and specific eradication of folate receptor-expressing cancer cells by engaging CAR-T cells in in vitro and in vivo models of ovarian cancer.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts) constitute a promising class of cancer immunotherapeutics.[1] CAR-Ts link antibody-mediated major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent recognition of cancer cell surface antigens to the power of T-cell-mediated killing. Two CD19-targeting CAR-Ts have received FDA approval thus far; (i) tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah®; Novartis) for the treatment of patients up to 25 years old with refractory or relapsed pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (pre-B-ALL) in 2017[2] and adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 2018[3]; and (ii) axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta®; Gilead) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL in 2017.[3–4] Unlike conventional pharmaceuticals, CAR-Ts are living drugs. They are built by transducing autologous T cells from cancer patients with chimeric antigen receptors that fuse an extracellular antibody fragment, typically a scFv, to a transmembrane segment, followed by the cytoplasmic signaling domain of a T cell costimulatory receptor (typically CD28 or 4–1BB) and the cytoplasmic signaling domain of CD3ζ of the T-cell receptor complex. As such, a CAR-T links antibody-mediated binding to T-cell activation.[5] CAR-Ts face two key challenges. First, the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) production of CAR-Ts is logistically challenging. It involves the collection, activation, transduction, expansion, cryopreservation, and infusion of autologous T cells.[6] Second, as living drugs, CAR-Ts can persist for extended periods of time, possibly forever, in the cancer patient. The FDA-approved CAR-Ts are not equipped with a safety switch to prevent or mitigate on-target-off-tumor and off-target-off-tumor toxicity including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Addressing these adverse events by advanced CAR-T engineering and CAR-T target discovery has become a major effort.

Although two CAR-Ts have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma, their therapeutic utility for solid malignancies, which make up 90% of all cancers, remains to be established clinically.[7] A major impediment is the immunosuppressive tumor environment that counteracts T-cell infiltration, activation, and recruitment.[8] Another challenge is the identification of cell surface receptors that are selectively expressed on cancer cells and can serve as targets for CAR-Ts that do not harm healthy cells and tissues. In this regard, the pocketome fraction of the cancer cell surfaceome, which comprises thermodynamically (enthalpically and/or entropically) favored small molecule binding sites on cancer cell surface receptors and their complexes, affords a vast targetable and druggable space that is only accessible to small molecules. As such, small molecules can complement natural recognition repertoires, including antibodies. However, compared to antibodies, small molecules have inappropriate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties for cancer immunotherapy. A variety of chemically programmed antibodies, chemically programmed bispecific antibodies, and related concepts have sought to address these shortcomings,[9] and methods that can endow small molecules with the ability to recruit and activate CAR-Ts have also been reported.[10]

Building on a switchable CAR-T platform that is controlled by a conventional antibody fragment in Fab format[11], we adapted the system to control by a chemically programmed Fab (cp-Fab). This effectively transfers control of T-cell recruitment and activation to a cancer cell surfaceome-targeting small molecule. The cp-Fab is assembled in vitro and can be used to charge CAR-Ts ex vivo or in vivo. Our cp-Fab/CAR-T system is highly versatile, with the only variable component being the small molecule, thus enabling broad utility for probing the pocketome with the power of CAR-Ts.

To establish proof-of-concept for the cp-Fab/CAR-T system, we focused on targeting the folate binding site of folate receptor 1 (FOLR1; a.k.a. folate receptor α). FOLR1 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoprotein, which binds folate with nanomolar affinity to facilitate receptor-mediated endocytosis. Rapidly growing solid malignancies, including ovarian and lung cancer, depend on folate (a.k.a. vitamin B9) for metabolism and nucleic acid synthesis. To compete with healthy cells and tissues for folate, FOLR1 is highly overexpressed in these cancers. This has made FOLR1 an attractive target for both small molecule- and antibody-based diagnostic and therapeutic reagents[12], including chemically programmed T-cell engaging bispecific antibodies[13] and CAR-Ts.[10, 14] Conventional CAR-Ts targeting FOLR1 have also been reported[15] and translated to phase I clinical trials for ovarian cancer therapy (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03585764). On the basis of this collective body of work, we elected to probe the folate binding site of FOLR1 as a representative pocketome target for cp-Fab/CAR-Ts.

Results

Design and engineering of a cp-Fab/CAR-T system

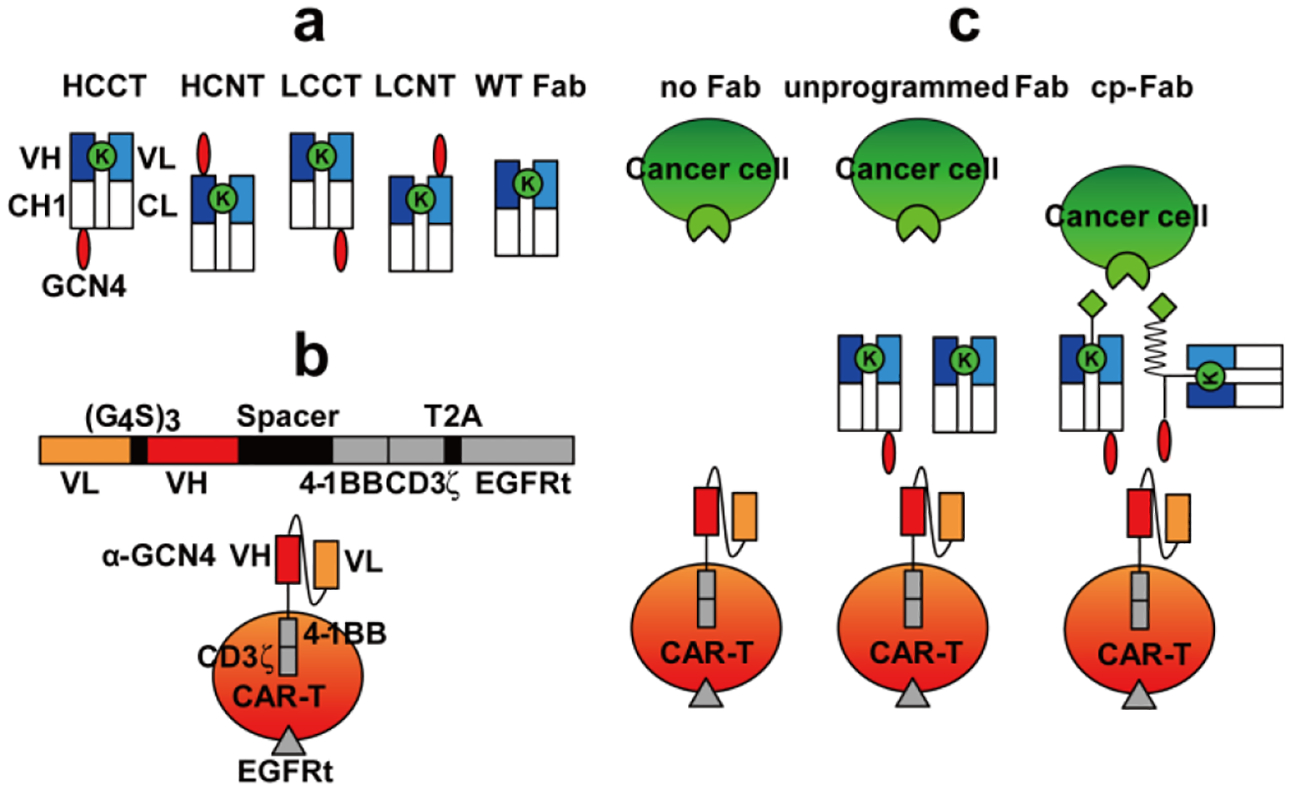

The cp-Fab/CAR-T platform was designed as a two-component system combining (i) a cp-Fab that displays a peptide tag through either recombinant fusion or chemical programming and (ii) a generic and inert CAR-T that binds to the peptide tag (Figure 1). CAR-T and cp-Fab are administered separately, effectively comprising an inherent on/off switch. This design builds on an established platform that uses a conventional Fab to control a generic and inert CAR-T.[11, 16]

Figure 1. Design and concept of cp-Fab/CAR-T system.

(a) Schematic illustration of the four tagged h38C2 Fabs with the reactive Lys (green) and the C- or N-terminally appended GCN4 peptide (NYHLENEVARLKKL; red). The linker sequence between the peptide and Fab is G4S (HCCT, LCCT, and LCNT) or LVGEAAAKEAAAKA (HCNT). WT h38C2 Fab without tag is shown on the right. (b) Schematic illustration of the CAR-T with scFv 52SR4 as anti-GCN4 peptide recognition domain fused to 4–1BB and CD3ζ cytoplasmic signalling domains. (c) The CAR-Ts only serve as functional effector cells in the presence of cp-Fab (right) but not unprogrammed Fab (middle) or no Fab (left), effectively rendering control of the CAR-T to a small molecule (light green) that targets a cancer cell surface receptor (light green). Chemical programming of WT h38C2 Fab includes the GCN4 peptide (red) synthetically fused to the small molecule (light green) via a modular PEG spacer (zigzag line).

The cp-Fab is based on the catalytic antibody h38C2 which harbors an unprotonated lysine (Lys) residue at the bottom of its 11-Ǻ deep active site.[17] The unique reactivity of this Lys can be harnessed for site-specific conjugation to small molecules with 1,3-diketone, β-lactam, or, as we have shown recently,[18] methylsulfone phenyl oxadiazole functionality. In the concept of chemically programmed antibodies[9a, 19], h38C2 serves as invariable biological component for covalent conjugation to a variable chemical component that targets small molecule binding sites in the pocketome fraction of the cell surfaceome. We built two different types of cp-Fabs. In one, the h38C2 Fab scaffold is recombinantly fused to a non-immunogenic[11] 14-amino acid (aa) peptide (NYHLENEVARLKKL) derived from yeast transcription factor GCN4 to the C-termini (CT) or N-termini (NT) of heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC). Depending on the location of the peptide tag, we refer to these tagged Fabs as HCCT, HCNT, LCCT, and LCNT (Figure 1a). The other uses an untagged or wild-type (WT) h38C2 Fab scaffold (Figure 1a) that procures the GCN4 peptide required for CAR-T recruitment through chemically programming. All Fabs were composed of two different polypeptide chains encoded by two separate expression cassettes in the mammalian expression vector pCEP4. The two encoding plasmids of each Fab were combined by transient cotransfection into Expi293F cells. Following affinity chromatography that yielded ~30 mg/L tagged and WT Fab, nonreducing and reducing SDS-PAGE showed the expected bands (Supplementary Figure 1a). To test the integrity of the recombinantly fused peptide tag, we cloned, expressed, and purified scFv 52SR4[20] in scFv-Fc format and confirmed its binding to all four tagged Fabs by ELISA (Supplementary Figure 1b).

The generic and inert CAR-T was generated by lentiviral transduction of primary human T cells. The lentiviral vector[21] contained an expression cassette (Figure 1b) that fuses the sequences of a scFv 52SR4 in VL-(G4S)3-VH format to a mutated human IgG4 hinge, followed by the transmembrane segment of CD28 and the cytoplasmic signaling domains of 4–1BB and CD3ζ Downstream of the CAR and linked by a T2A ribosomal skip element, it encodes a truncated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRt) sequence.[22] The binding domain of the CAR, scFv 52SR4, is a ribosome display-evolved mouse scFv that binds the GCN4 peptide with picomolar affinity (Kd = 5 pM)[20] but does not bind to any human antigens.[11] This renders the CAR-T inert in the absence of the cp-Fab. Due to its exceptionally high affinity, the cp-Fab can switch on the CAR-T at low systemic concentrations (Figure 1c). We lentivirally transduced primary human T cells that had been isolated and expanded from commercial healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) ex vivo. Using an anti-EGFRt monoclonal antibody (mAb), flow cytometry revealed 65–85% transduction efficiency (Supplementary Figure 2).

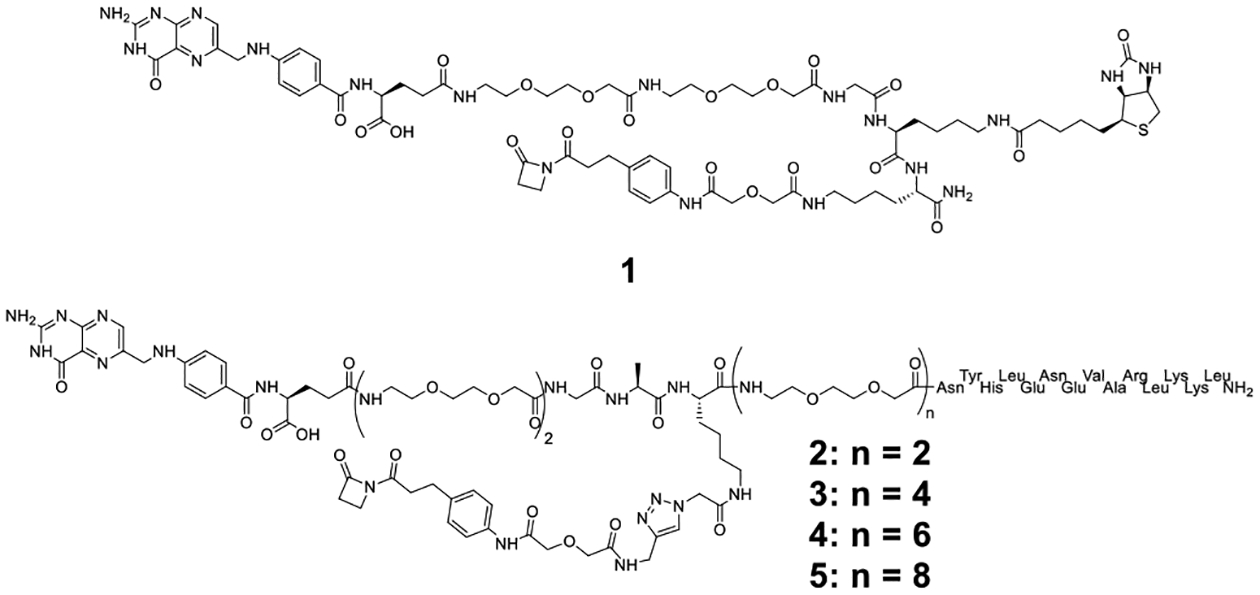

Trifunctional β-lactam-biotin-folate compound 1 (Figure 2a) was used for chemical programming of the four tagged Fabs. The β-lactam group mediates highly efficient and selective hapten-driven covalent conjugation to the reactive Lys in the active site of h38C2.[23] The biotin group enables detection. The folate group mediates FOLR1 binding. Chemical programming was carried out with 4 equivalents of compound in PBS at room temperature for 4 h. A catalytic assay based on the retro-aldol degradation of methodol by h38C2[17, 24] revealed complete covalent conjugation at the reactive Lys residue (Supplementary Figure 3a). Analysis by flow cytometry showed that the two cp-Fabs with C-terminal peptide tag (HCCT_1 and LCCT_1) bound FOLR1-expressing IGROV-1 and SKOV-3 human ovarian cancer cells while the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs (HCCT and LCCT) did not (Supplementary Figure 3c). By contrast, the Fabs with N-terminal peptide tag (HCNT and LCNT) revealed background binding in the absence of chemical programming. Importantly, the four cp-Fabs were found to bind the CAR-T as efficiently as the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs, demonstrating that the conjugated compound did not interfere with the cp-Fab/CAR-T interaction (Supplementary Figure 3c).

Figure 2. Structure of FOLR1-targeting compounds.

Structure of β-lactam-biotin-folate compound 1 and trifunctional β-lactam-GCN4-folate compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5.

For chemical programming of the WT Fab, we synthesized the four trifunctional β-lactam-GCN4-folate compounds shown as 2, 3, 4, and 5 in Figure 2. The compounds differ by the lengths of the polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer between the GCN4 peptide and the folate group. Following β-lactam-mediated conjugation, compounds 2–5 endow the WT Fab with the ability to bispecifically engage CAR-T and FOLR1-expressing cancer cells. Chemical programming was carried out as for the tagged Fabs and validated by the same catalytic assay (Supplementary Figure 3b). WT Fab_2, WT Fab_3, WT Fab_4, and WT Fab_5 bound to both CAR-Ts and IGROV-1 and SKOV-3 cells whereas the unprogrammed WT Fab did not bind to either (Supplementary Figure 3c).

In vitro validation of the cp-Fab/CAR-T system

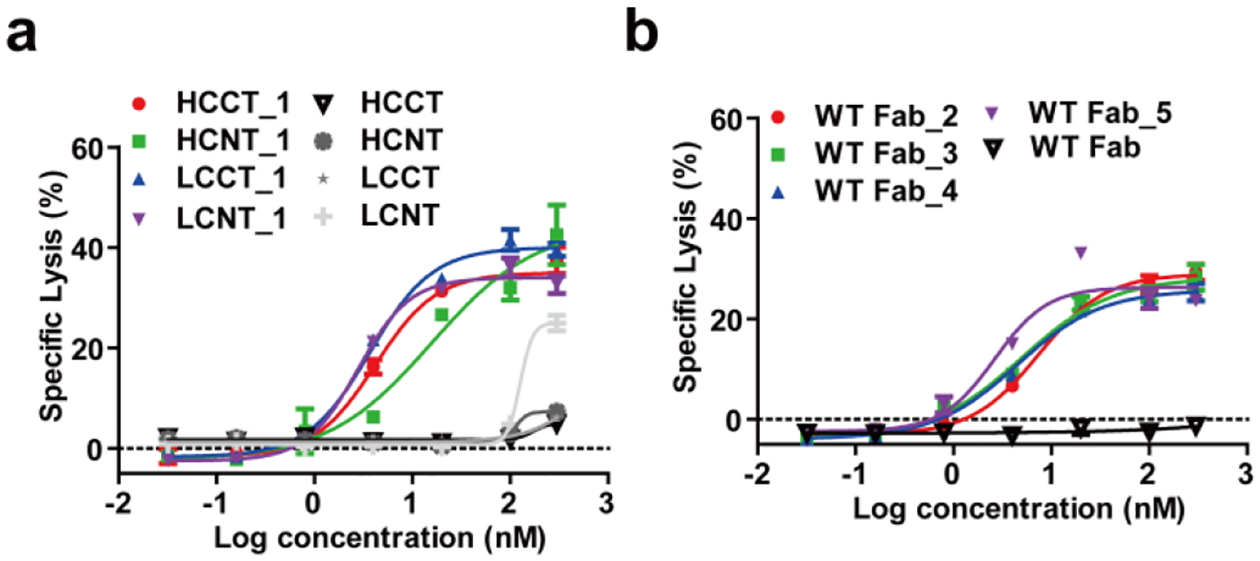

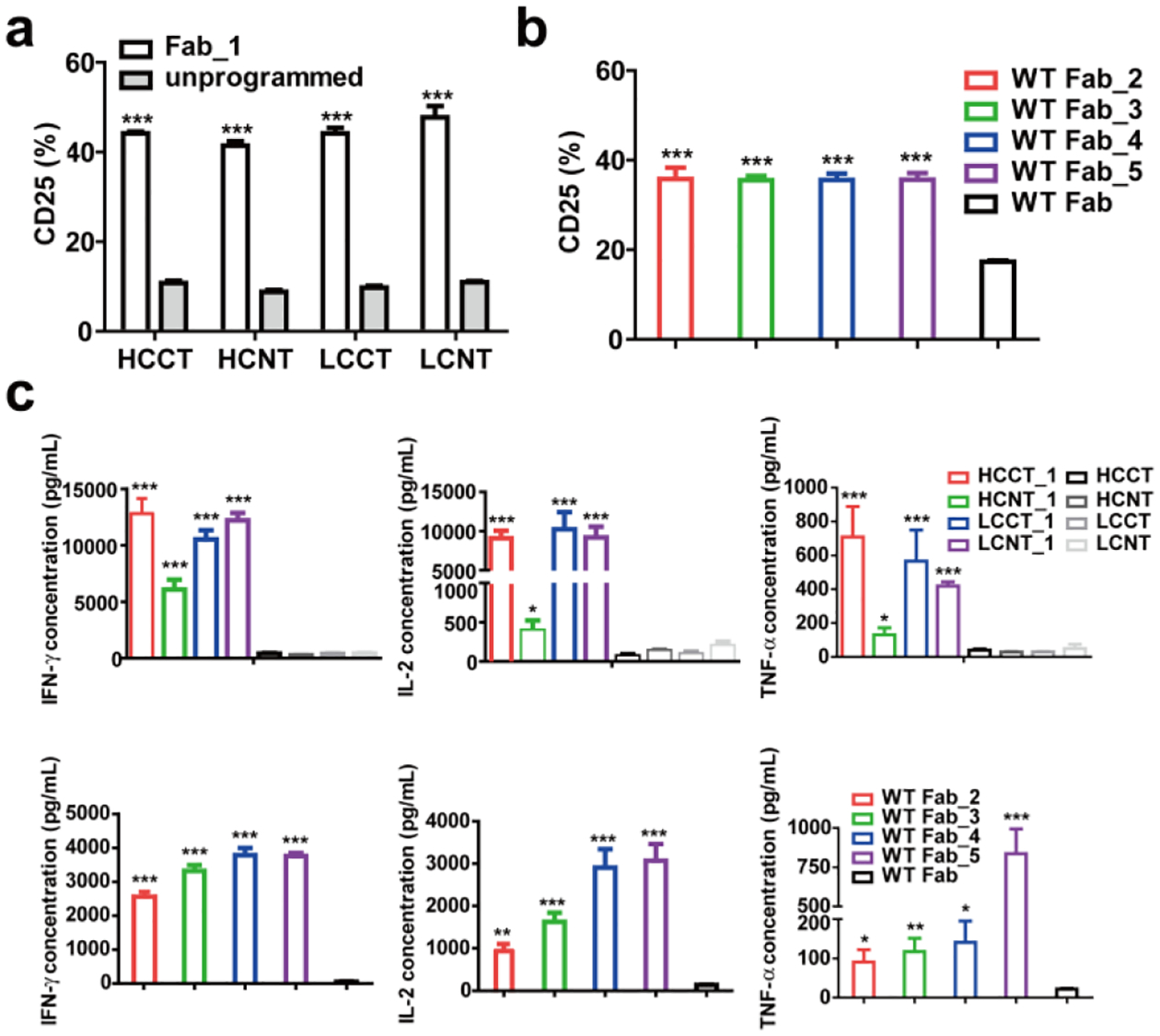

Next, we compared the FOLR1-targeting cp-Fabs for their ability to mediate the killing of IGROV-1 and SKOV-3 cells by the CAR-T. Specific lysis of target cells after 24 h incubation with cp-Fab concentrations ranging from 32 pM to 300 nM at an effector-to-target cell ratio of 10:1 was assessed. The cp-Fabs that were based on the tagged Fab, i.e. HCCT_1, HCNT_1, LCCT_1, and LCNT_1, but not the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs, mediated killing of IGROV-1 (Figure 3a) and SKOV-3 (Supplementary Figure 4a) cells with single to double digit nanomolar EC50 values (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the cp-Fabs that were based on the WT Fab, i.e. WT Fab_2, WT Fab_3, WT Fab_4, WT Fab_5 revealed similar potency and selectivity as the cp-Fabs that were based on the tagged Fab (Figure 3b, Supplementary Figure 4b, and Supplementary Table 1). For all cp-Fabs, cytotoxicity was strictly dependent on T-cell transduction (Supplementary Figure 4c–f). As analyzed by flow cytometry and ELISA, respectively, T-cell activation marker CD25 on CAR-Ts and secretion of type I cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α was robustly upregulated after 24 h incubation with 20 nM cp-Fabs, but not the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs, in the presence of the target cells (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 5). This T-cell activation was also strictly dependent on T-cell transduction (Supplementary Figure 6). Collectively, the cp-Fab-controlled target cell killing, T-cell activation, and cytokine secretion validated the cp-Fab/CAR-T system in vitro. We chose cp-Fabs, LCCT_1 and WT Fab_5 for subsequent in vivo validation based on their single digit nanomolar EC50 values and the low background binding and cytotoxicity of unprogrammed Fab LCCT. First, we validated LCCT_1 and WT Fab_5 by mass spectrometry (MS). LCCT and LCCT_1 revealed a molecular weight of 49,925 and 51,511 Da, respectively (Supplementary Figure 7a, b). This observed increase of 1,586 Da matches the anticipated increase of 1,586.75 for the conjugation of a single molecule of compound 1 to LCCT. WT Fab and WT Fab_5 revealed a molecular weight of 47,901 and 52,212 Da, respectively (Supplementary Figure 7c, d). This observed increase of 4,311 Da matches the anticipated increase of 4,311.74 for the conjugation of a single molecule of compound 5 to the WT Fab.

Figure 3. In vitro activity of cp-Fab/CAR-T.

Cytotoxicity of the FOLR1-targeting cp-Fab/CAR-T against IGROV-1 cells with titration of cp-Fabs based on tagged (a) or WT (b) h38C2 Fabs was tested at an E:T ratio of 10:1 and measured after 24 h incubation. Cytotoxicity mediated by the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs was also investigated. Shown are mean ± SD values from independent triplicates. The control experiments with untransduced T cells are shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Figure 4. CAR-T activation mediated by cp-Fabs.

The CAR-T was incubated with 20 nM of the indicated FOLR1-targeting cp-Fabs or the corresponding unprogrammed Fabs in the presence of IGROV-1 cells at an E:T ratio of 10:1 for 24 h. The percentage of activated T cells based on CD25 expression after incubation with cp-Fabs based on tagged (a) or WT (b) h38C2 Fabs was measured by flow cytometry. Cytokines released from the T cells in the presence of cp-Fabs based on tagged (c) or WT (d) h38C2 Fabs were measured by ELISA. Shown are mean ± SD values for independent triplicates. An unpaired two-tailed t-test was used to analyze significant differences (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

In vivo validation of the cp-Fab/CAR-T system

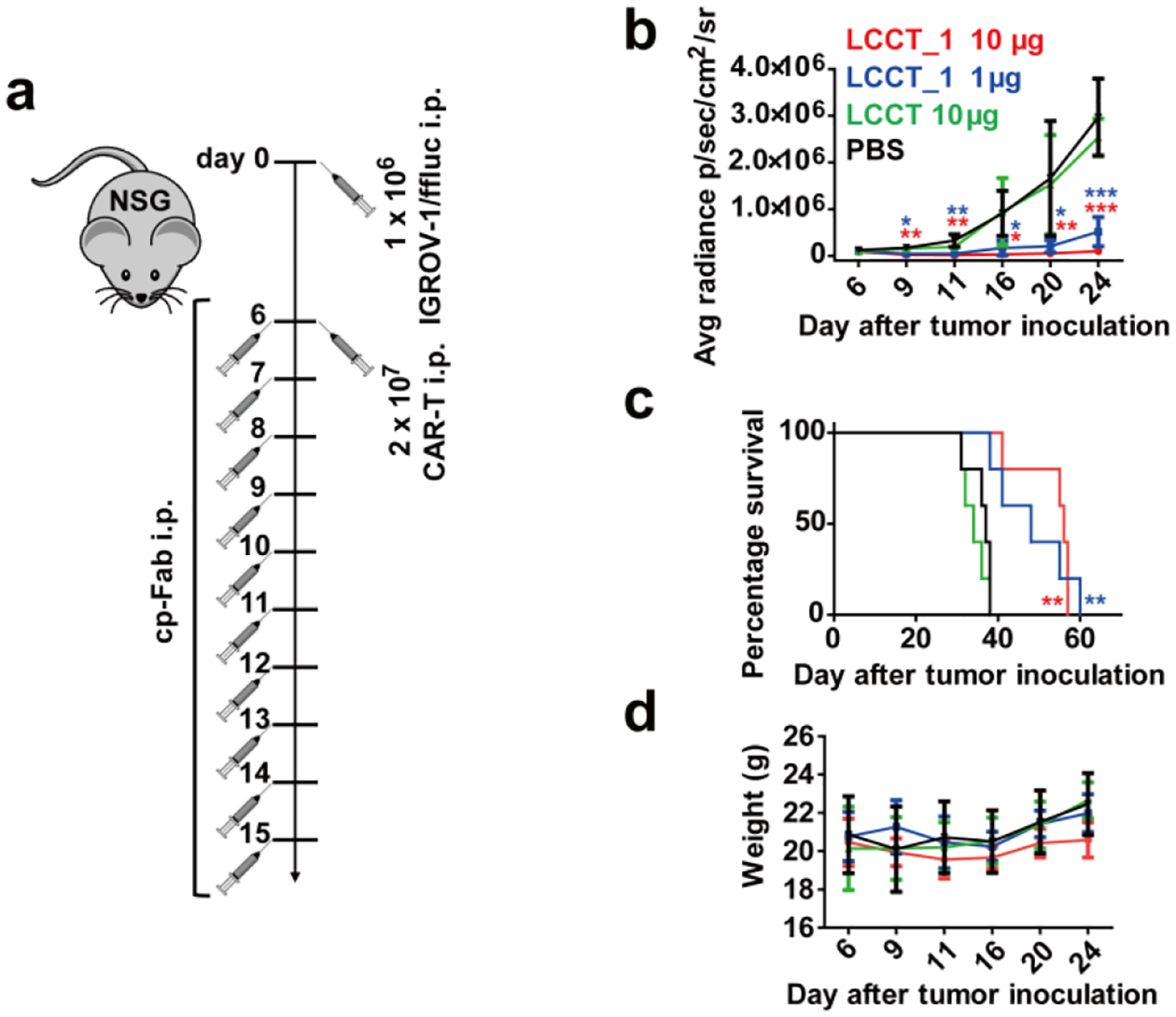

To investigate the activity of the cp-Fab/CAR-T system in vivo, we used a mouse model of human ovarian cancer that is based on injecting IGROV-1 cells transfected with firefly luciferase (ffluc) intraperitoneally (i.p.) into NOD/SCID/IL-2RYnull (NSG) mice[13b] (Figure 5a). Intraperitoneal xenografts of IGROV-1 cells in immunodeficient mice mimic the human disease with respect to carcinomatosis and ascites and have been widely used for preclinically assessing ovarian cancer therapeutics. We carried out two in vivo studies to evaluate the anti-tumor efficacy of LCCT_1 and WT Fab_5, respectively. In the first study, four cohorts of five female NSG mice each were injected i.p. with 1 × 106 IGROV-1/ffluc cells. After six days, the mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 107 CAR-Ts. After 6 h, 10 μg (cohort 1) and 1 μg (cohort 2) of LCCT_1, 10 μg of unprogrammed LCCT (control cohort 3), and vehicle (PBS) alone (control cohort 4) were administered i.p. in a 100-μL volume. All four cohorts were treated with a total of one dose of CAR-T and 10 daily doses of cp-Fab, Fab, or PBS. Note that all experiments were conducted without reducing endogenous folate concentrations in the mice. To assess the response to the treatment, in vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed prior to the first dose and then every 3–5 days (Supplementary Figure 8). Control cohorts 3 and 4 revealed aggressive tumor growth without significant difference (Figure 5b). Treatment with the higher dosage of the LCCT_1 (cohort 1) robustly decreased tumor burden in the first week and significantly stalled further tumor growth. The lower dosage (cohort 2) revealed significant tumor growth retardation but relapsed immediately when the treatment ceased (Figure 5b). Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed that both lower and higher dosage of the cp-Fab significantly prolonged survival when compared to vehicle alone (Figure 5c). No significant weight loss or other obvious signs of toxicity were observed during the treatment (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. In vivo activity of cp-Fab/CAR-T based on LCCT_1.

(a) Four cohorts of NSG mice (n = 5) were inoculated with 1 × 106 IGROV-1/ffluc cells via i.p. injection. After 6 days, 2 × 107 CAR-Ts and LCCT_1 (1 μg or 10 μg) or unprogrammed LCCT (10 μg) or vehicle alone (PBS) were administered by the same route. The mice received a total of one dose of CAR-T and 10 doses of LCCT_1 or controls daily. (b) Starting on day 6, all 20 mice were imaged (see Supplementary Figure 8) and their radiance was recorded (mean ± SD). Significant differences between cohorts treated with LCCT_1 and PBS were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). (c) Corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves with p-values using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (**, p < 0.01). (d) The weight of all 20 mice was recorded on the indicated days (mean ± SD).

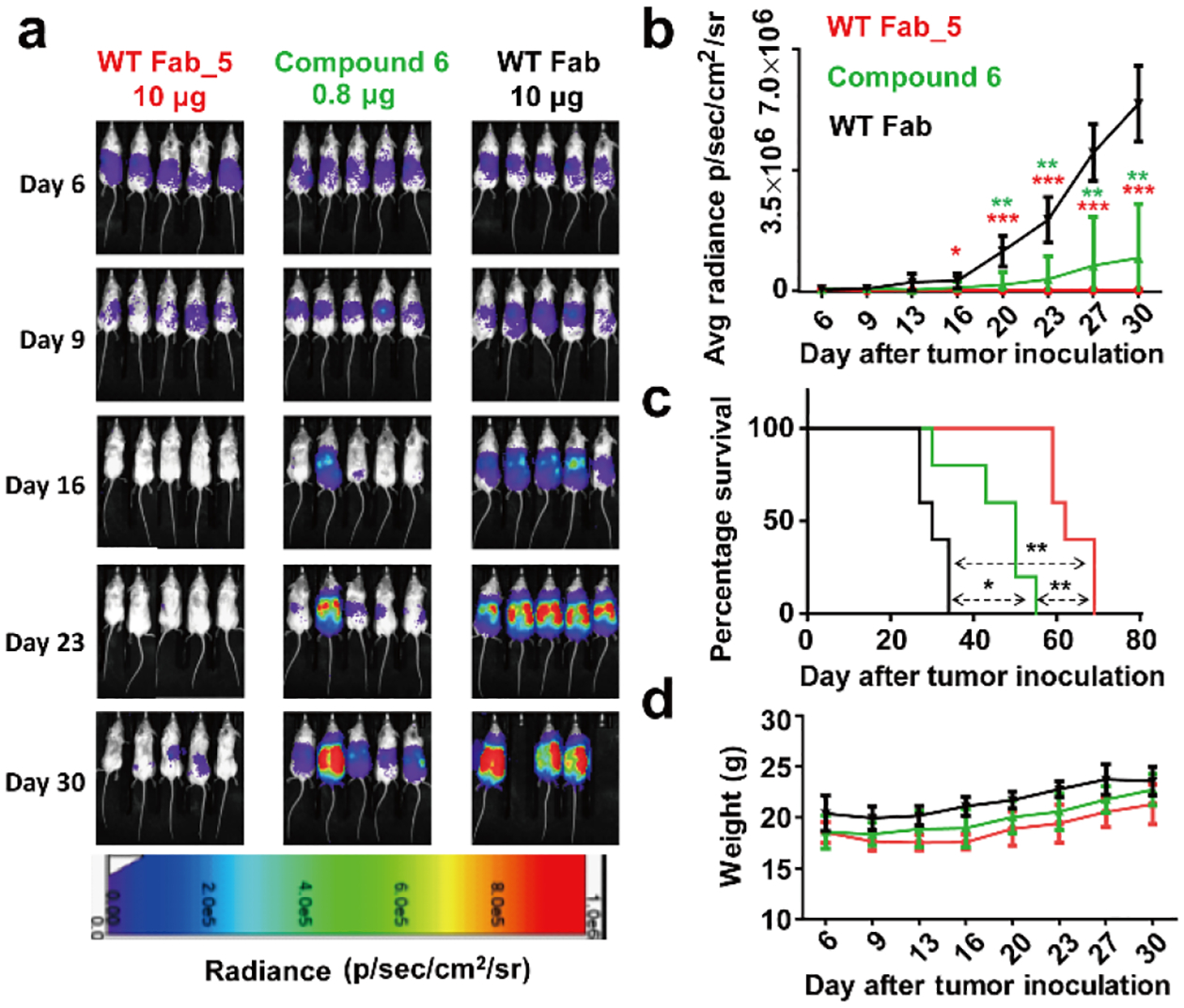

For the second in vivo study based on WT Fab_5, we included bifunctional GCN4-folate compound 6 for comparison. Compound 6 (Supplementary Figure 9a) differs from trifunctional β-lactam-GCN4-folate compound 5 (Figure 2) by lack of the β-lactam group. As such, compound 6 can serve as small molecule-based bispecific adapter control to the cp-Fab-based bispecific adapter WT Fab_5. The ability of compound 6 to simultaneously bind to 52SR4 scFv-Fc and cell surface FOLR1 on IGROV-1 cells was demonstrated by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 9b). The same dosing and imaging procedure used for the first in vivo study was repeated. In brief, 10 μg WT Fab_5 (cohort 1), an equimolar amount of compound 6 (cohort 2), and 10 μg of unprogrammed WT Fab (control cohort 3) were administered. As shown in Figure 6, treatment with WT Fab_5 robustly decreased tumor burden and significantly stalled further tumor growth. By contrast, aggressive tumor growth was observed for the unprogrammed WT Fab. Compound 6 revealed significant tumor growth retardation but relapsed immediately when the treatment ceased (Figure 6a, b). Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed that the cp-Fab significantly prolonged survival compared to compound alone or unprogrammed Fab alone (Figure 6c). No significant weight loss was observed during the treatment (Figure 6d). However, temporal hair loss and behavioral changes indicating graft-versus-host disease were observed in the first few days after CAR-T injection.

Figure 6. In vivo activity of cp-Fab/CAR-T based on WT Fab_5.

Three cohorts of NSG mice (n = 5) were inoculated with 1 × 106 IGROV-1/ffluc cells via i.p. injection. After 6 days, 2 × 107 CAR-Ts and WT Fab_5 (10 μg), an equimolar amount of compound 6, or unprogrammed WT Fab (10 μg) were administered by the same route. The mice received a total of one dose of CAR-T and 10 doses of cp-Fab, compound, or Fab daily. (a) Bioluminescence images of all 15 mice were taken from day 6 (before treatment) to day 30 (after treatment) at the indicated time points. (b) Starting on day 6, all 15 mice were imaged and their radiance was recorded (mean ± SD). Significant differences between cohorts treated with WT Fab_5 and WT Fab or compound 6 and WT Fab were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). (c) Corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves with p-values using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). (d) The weight of all 15 mice was recorded on the indicated days (mean ± SD).

Pharmacokinetic properties of cp-Fabs

To further explore the dynamic activation of the cp-Fab/CAR-T system, we carried out a pharmacokinetic (PK) study with LCCT_1 in mice to examine its circulatory half-life and other PK parameters. Four female CD-1 mice were injected i.p. with 8 mg/kg of LCCT_1. Unprogrammed LCCT was analyzed in a parallel cohort. Blood samples were withdrawn at various time points over a period of one week, and plasma was prepared. The cp-Fab or Fab concentration in the plasma was measured with a sandwich ELISA using immobilized 52SR4 scFv-Fc for capture and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human Fab polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) for detection (Supplementary Figure 10). Analysis of the PK parameters by two-compartment modeling revealed t1/2 values (mean ± SD) of LCCT_1 and LCCT, respectively, of 16.4 ± 8.7 h and 14.6 ± 5.1 h (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of LCCT_1 and LCCT.[a]

| t1/2 (h) | AUC (μg/mL × h) | CL (mL/h/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCCT_1 | 16.4 ± 8.7 | 62.0 ± 20.2 | 132.0 ± 39.3 |

| LCCT | 14.6 ± 5.1 | 77.9 ± 39.4 | 109.8 ± 35.7 |

Mean ± SD values from 4 mice.

Discussion

Macromolecules on cell surfaces, collectively known as the cell surfaceome,[25] are predominantly targeted with large molecules such as antibodies. By contrast, the pocketome fraction of the cell surfaceome, which is only accessible to small molecules, constitutes a rich subset of binding sites with immense potential diagnostic and therapeutic utility.[26] Still largely uncharted territory, the exploration of this vast targetable and druggable space with increasingly complex chemical libraries is well underway.[27] For example, a global industry-academia partnership campaign known as Target 2035 aims at the generation of small molecules that bind with high affinity and specificity to all proteins, explicitly including the cell surfaceome.[28] However, compared to antibodies, small molecules that target cell surface receptors are disadvantaged by their less confined biodistribution, shorter circulatory half-life, and inability to communicate with the immune system. Based on these considerations, we have had a longstanding interest in developing technologies that endow small molecules with the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of antibodies.[9a] Specifically, our studies have focused on conceptually new approaches for cancer therapy at the interface of chemistry and immunology. In the current study, we designed, engineered, and validated in vitro and in vivo CAR-Ts, which can be controlled with an antibody fragment that is chemically programmed with a pocketome-targeting small molecule.

Chemical programming in our cp-Fab/CAR-T system is achieved by site-specific conjugation of a variable small molecule to an invariable Fab. The Fab, which is derived from a catalytic antibody, harbors a uniquely reactive Lys that is used for hapten-driven conjugation to a β-lactam derivative of a small molecule. Only by chemical programming does the Fab gain the ability to target the cell surfaceome. Akin to the unprogrammed Fab, the previously reported[11] scFv 52SR4-based CAR-T component of our system, is inactive on its own. By interacting with a 14-aa GCN4 peptide appended to one of the four C- or N-termini of the Fab, it gains the ability to become activated in the presence of target cells.[11] By using a chemically programmed instead of a conventional Fab, we adapted this system to small molecules and, in doing so, made the pocketome accessible to CAR-T therapy. The availability of four different sites for the GCN4 peptide allows the testing of different cp-Fab/CAR-T assemblies for optimal cytolytic synapse formation between T cell and target cell. We found that an N-terminal fusion to the heavy chain (HCNT) attenuated the potency of the cp-Fab. While this observation may be confined to the folate/FOLR1 system studied here, it is possible that the vicinity of the small molecule conjugated to the reactive Lys at position 99 of the heavy chain variable domain (Lys99) and the GCN4 peptide appended to its N-terminus confers mutual steric hindrance despite the longer spacer we used for this configuration. In fact, the crystal structure of mAb 33F12, which is highly related to mAb 38C2 in terms of aa sequence identity and catalytic activity, revealed that Lys99 and the N-terminus of the heavy chain variable domain are in close proximity.[29] The other three sites of the GCN4 peptide (HCCT, LCCT, and LCNT) did not show a significant difference with respect to the potency of the cp-Fab. However, we found that HCNT and LCNT revealed higher background binding that appeared to translate to higher background in vitro cytotoxicity at high concentrations. Thus, HCCT and LCCT, the latter of which we chose for in vivo validation, emerged as the most suitable formats for cp-Fabs.

To make our cp-Fab/CAR-T platform more adaptable, we synthesized the GCN4 peptide together with folate as a trifunctional compound. In this system, chemical programming of the h38C2 Fab introduces both CAR-T engagement via GCN4 peptide and target cell engagement via folate. Thus, unlike the tagged Fab, the WT Fab only serves as a carrier of a functionally self-sufficient small molecule. Through β-lactam-mediated conjugation to the carrier, the trifunctional compound acquires the pharmacokinetic properties of the Fab. Four trifunctional β-lactam-GCN4-folate compounds with PEG spacers of different lengths (from n=2 to n=8) between GCN4 peptide and folate were synthesized and investigated. Length variation allowed us to investigate the optimal distance between two functional groups that have to simultaneously engage cell surface receptors on different cells to promote cytolytic synapse formation. Although all four trifunctional compounds were comparable with respect to CAR-T and target cell binding, the compound with the longest PEG spacer (n=8) was superior in terms of mediating in vitro cytotoxicity, T-cell activation, and cytokine secretion. Similar to conventional CAR-Ts that can be optimized by tailoring the length of the extracellular spacer between scFv and transmembrane segment,[21] the PEG spacer of our trifunctional compound serves as a modular element for fine tuning a functional bridge between a pocket in the target cell surfaceome and the CAR-T. Custom fitting can also be achieved with the cp-Fabs that are based on the tagged Fab. Here, a modular element can be introduced between the β-lactam and the pocketome-targeting small molecule. However, introducing the GCN4 peptide by chemical programming rather than recombinant fusion may mitigate the immunogenicity of the cp-Fab. Perhaps more importantly, the ability to chemically program CAR-T engagement eliminates the need for using a canonical L-peptide such as the GCN4 peptide we used here. It opens the door for building cp-Fab/CAR-T platforms that are based on noncanonical peptides, peptidomimetics, and other small molecules that bind with high affinity and specificity to a generic and inert CAR-T but cannot be recombinantly fused to a cp-Fab switch.

Chemically programmed CAR-T platforms can be designed to be activatable and regulatable by a small molecule directly. Kim et al.[10a] used folate conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (folate-FITC) in combination with an anti-FITC CAR-T for in vitro validation of this concept. Notably, a similar system[10b] with a folate-FITC switch controlling an anti-FITC CAR-T, was recently shown to avert CRS in an in vivo model.[14] We already showed that the small molecule can be synthetically fused to the GCN4 peptide as alternative to its conjugation to a GCN4 peptide-appended Fab. As such, it should be able to recruit and activate the same scFv 52SR4-based CAR-T in the presence of target cells. However, we reasoned that a cp-Fab would have superior pharmacological properties compared to a peptide conjugate. In fact, we measured a circulatory half-life of ~16 h after i.p. injection of the cp-Fab that was not influenced by chemical programming. A previous study reported a half-life of only 90 min for a small molecule-based bispecific adapter targeting FOLR1.[30] The longer circulatory half-life of a cp-Fab should permit a lowering of the frequency of administration from every day (q.d.) to every other day (q.o.d.). By contrast, a peptide conjugate would likely require more frequent, if not continuous administration. In fact, using equimolar dosing at the same frequency, we found that Fab conjugation significantly improved in vivo activity in terms of both delayed tumor growth and prolonged survival compared to the unconjugated compound. Nonetheless, a peptide conjugate with short circulatory half-life would enable an even faster switch off than a cp-Fab in case serious adverse events are experienced by the patient. Further preclinical investigations require immunocompetent mouse models that can deliver data on both activity and toxicity.

In addition to providing more control, switchable CAR-T platforms are also highly versatile. In these systems, a generic and inert CAR-T is switched on by a variable antibody or antibody fragment.[31] Here, we have broadened their utility further by replacing antibody-based recognition with small molecule-based recognition. Collectively, the virtually unlimited availability of adapters that can switch on a generic and inert CAR-T should expedite the in vitro and in vivo screening toward optimal Fab/CAR-T and cp-Fab/CAR-T systems for a given antibody or small molecule target, respectively. Furthermore, its modular composition should expedite preclinical and clinical studies. Switchable CAR-T platforms, including our new cp-Fab/CAR-T system, also permit administration of different adaptors simultaneously or sequentially. The use of multiple adaptors could effectively evolve CAR-T therapy from monoclonal to polyclonal recognition to counteract target cell heterogeneity and resistance in cancer.

At present, it is not known whether a switchable CAR-T platform can achieve cures as have been observed for conventional CD19-targeting CAR-Ts in pre-B-ALL.[1] It is possible that long-term persistence of the CAR-T and suppression of the cancer requires constant or intermittent presence of the adaptor. Notably, using a mouse model of the Fab/CAR-T system, Viaud et al.[32] showed that metronomic administration of the Fab induces memory and expansion of CAR-Ts. In our mouse model of ovarian cancer growing aggressively in the peritoneum, we observed complete responses in the presence of the adaptor but consistent relapses after treatment ceased. It remains to be determined whether longer treatments in this mouse model can further prolong survival. Notably, unlike a Fab that only binds human FOLR1 on the xenografted cancer cells, our cp-Fab binds to both human and mouse folate receptors, thus encountering a physiologically relevant sink in the host. In addition, our cp-Fab competes for human FOLR1 binding with endogenous folate, which has a >10-fold higher serum concentration in laboratory mice (~250 nM) compared to humans (~20 nM).[33] Considering this, it is conceivable that small molecules without host sink and without competition by endogenous small molecules perform even better in our cp-Fab/CAR-T system.

Conclusion

We developed a novel CAR-T platform that is based on a chemically programmed on/off switch. Control of a generic and inert CAR-T is rendered to a small molecule that targets a pocket in the cell surfaceome and is site-specifically conjugated to an antibody fragment in Fab format. For proof-of-concept, we used folate for chemical programming and demonstrated potent and specific CAR-T-mediated eradication of folate receptor-expressing cancer cells in in vitro and in vivo models of ovarian cancer. Our system engenders CAR-Ts with access to the pocketome, a vast targetable and druggable space that is inaccessible to conventional CAR-Ts and other antibody-based cancer therapies. As such, we have developed a new interface between chemistry and immunology that endows pocketome-targeting small molecules with the power of CAR-T therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

At The Scripps Research Institute (Jupiter, FL, USA), we thank Li Lin and Dr. Michael D. Cameron for their help with analyzing the PK study, and Dr. George Tsaprailis for conducting and analyzing the LC-MS study. We also thank Prof. Hirokazu Tamamura from the Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan) for supporting the synthesis of compound 6. This study was supported by NIH grants R01 CA174844, R01 CA181258, and R01 CA204484 (to C.R.) and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (to T.R.B. Jr.). This is manuscript #29833 from The Scripps Research Institute.

References

- [1].a) June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC, Science 2018, 359, 1361–1365; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sadelain M, Riviere I, Riddell S, Nature 2017, 545, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].O’Leary MC, Lu X, Huang Y, Lin X, Mahmood I, Przepiorka D, Gavin D, Lee S, Liu K, George B, Bryan W, Theoret MR, Pazdur R, Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 1142–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chow VA, Shadman M, Gopal AK, Blood 2018, 132, 777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bouchkouj N, Kasamon YL, de Claro RA, George B, Lin X, Lee S, Blumenthal GM, Bryan W, McKee AE, Pazdur R, Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 1702–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989, 86, 10024–10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kohl U, Arsenieva S, Holzinger A, Abken H, Hum Gene Ther 2018, 29, 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Slaney CY, Wang P, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Cancer Discov 2018, 8, 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anderson KG, Stromnes IM, Greenberg PD, Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 311–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Rader C, Trends Biotechnol 2014, 32, 186–197; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rader C, Nature 2015, 518, 38–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Kim MS, Ma JS, Yun H, Cao Y, Kim JY, Chi V, Wang D, Woods A, Sherwood L, Caballero D, Gonzalez J, Schultz PG, Young TS, Kim CH, J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 2832–2835; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee YG, Marks I, Srinivasarao M, Kanduluru AK, Mahalingam SM, Liu X, Chu H, Low PS, Cancer Res 2019, 79, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rodgers DT, Mazagova M, Hampton EN, Cao Y, Ramadoss NS, Hardy IR, Schulman A, Du J, Wang F, Singer O, Ma J, Nunez V, Shen J, Woods AK, Wright TM, Schultz PG, Kim CH, Young TS, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E459–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Xia W, Low PS, J Med Chem 2010, 53, 6811–6824; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fernandez M, Javaid F, Chudasama V, Chem Sci 2018, 9, 790–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Cui H, Thomas JD, Burke TR Jr., Rader C, J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 28206–28214; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Walseng E, Nelson CG, Qi J, Nanna AR, Roush WR, Goswami RK, Sinha SC, Burke TR Jr., Rader C, J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 19661–19673; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Qi J, Hymel D, Nelson CG, Burke TR Jr., Rader C, Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee YG, Chu H, Lu Y, Leamon CP, Srinivasarao M, Putt KS, Low PS, Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Song DG, Ye Q, Carpenito C, Poussin M, Wang LP, Ji C, Figini M, June CH, Coukos G, Powell DJ Jr., Cancer Res 2011, 71, 4617–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Ma JS, Kim JY, Kazane SA, Choi SH, Yun HY, Kim MS, Rodgers DT, Pugh HM, Singer O, Sun SB, Fonslow BR, Kochenderfer JN, Wright TM, Schultz PG, Young TS, Kim CH, Cao Y, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E450–458; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cao Y, Rodgers DT, Du J, Ahmad I, Hampton EN, Ma JS, Mazagova M, Choi SH, Yun HY, Xiao H, Yang P, Luo X, Lim RK, Pugh HM, Wang F, Kazane SA, Wright TM, Kim CH, Schultz PG, Young TS, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2016, 55, 7520–7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rader C, Turner JM, Heine A, Shabat D, Sinha SC, Wilson IA, Lerner RA, Barbas CF 3rd, J Mol Biol 2003, 332, 889–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hwang D, Tsuji K, Park H, Burke TR Jr., Rader C, Bioconjug Chem 2019, 30, 2889–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rader C, Sinha SC, Popkov M, Lerner RA, Barbas CF 3rd, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 5396–5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zahnd C, Spinelli S, Luginbuhl B, Amstutz P, Cambillau C, Pluckthun A, J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 18870–18877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hudecek M, Sommermeyer D, Kosasih PL, Silva-Benedict A, Liu L, Rader C, Jensen MC, Riddell SR, Cancer Immunol Res 2015, 3, 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang X, Chang WC, Wong CW, Colcher D, Sherman M, Ostberg JR, Forman SJ, Riddell SR, Jensen MC, Blood 2011, 118, 1255–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gavrilyuk JI, Wuellner U, Barbas CF 3rd, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2009, 19, 1421–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].List B, Barbas CF 3rd, Lerner RA, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 15351–15355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Bausch-Fluck D, Goldmann U, Muller S, van Oostrum M, Muller M, Schubert OT, Wollscheid B, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E10988–E10997; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bausch-Fluck D, Hofmann A, Bock T, Frei AP, Cerciello F, Jacobs A, Moest H, Omasits U, Gundry RL, Yoon C, Schiess R, Schmidt A, Mirkowska P, Hartlova A, Van Eyk JE, Bourquin JP, Aebersold R, Boheler KR, Zandstra P, Wollscheid B, PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Parker CG, Galmozzi A, Wang Y, Correia BE, Sasaki K, Joslyn CM, Kim AS, Cavallaro CL, Lawrence RM, Johnson SR, Narvaiza I, Saez E, Cravatt BF, Cell 2017, 168, 527–541 e529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Gerry CJ, Schreiber SL, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 333–352; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goodnow RA Jr., Dumelin CE, Keefe AD, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 131–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Mullard A, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 733–736; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Carter AJ, Kraemer O, Zwick M, Mueller-Fahrnow A, Arrowsmith CH, Edwards AM, Drug Discov Today 2019, 24, 2111–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Barbas CF 3rd, Heine A, Zhong G, Hoffmann T, Gramatikova S, Bjornestedt R, List B, Anderson J, Stura EA, Wilson IA, Lerner RA, Science 1997, 278, 2085–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tummers QR, Hoogstins CE, Gaarenstroom KN, de Kroon CD, van Poelgeest MI, Vuyk J, Bosse T, Smit VT, van de Velde CJ, Cohen AF, Low PS, Burggraaf J, Vahrmeijer AL, Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3214432155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Darowski D, Kobold S, Jost C, Klein C, MAbs 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Viaud S, Ma JSY, Hardy IR, Hampton EN, Benish B, Sherwood L, Nunez V, Ackerman CJ, Khialeeva E, Weglarz M, Lee SC, Woods AK, Young TS, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E10898–E10906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Leamon CP, Reddy JA, Dorton R, Bloomfield A, Emsweller K, Parker N, Westrick E, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008, 327, 918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.