Abstract

Background

Accurate antibody tests are essential to monitor the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Lateral fow immunoassays (LFIAs) can deliver testing at scale. However, reported performance varies, and sensitivity analyses have generally been conducted on serum from hospitalised patients. For use in community testing, evaluation of fnger-prick self-tests, in non-hospitalised individuals, is required.

Methods

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on 276 non-hospitalised participants. All had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription PCR and were ≥21 days from symptom onset. In phase I, we evaluated five LFIAs in clinic (with finger prick) and laboratory (with blood and sera) in comparison to (1) PCR-confirmed infection and (2) presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies on two ‘in-house’ ELISAs. Specificity analysis was performed on 500 prepandemic sera. In phase II, six additional LFIAs were assessed with serum.

Findings

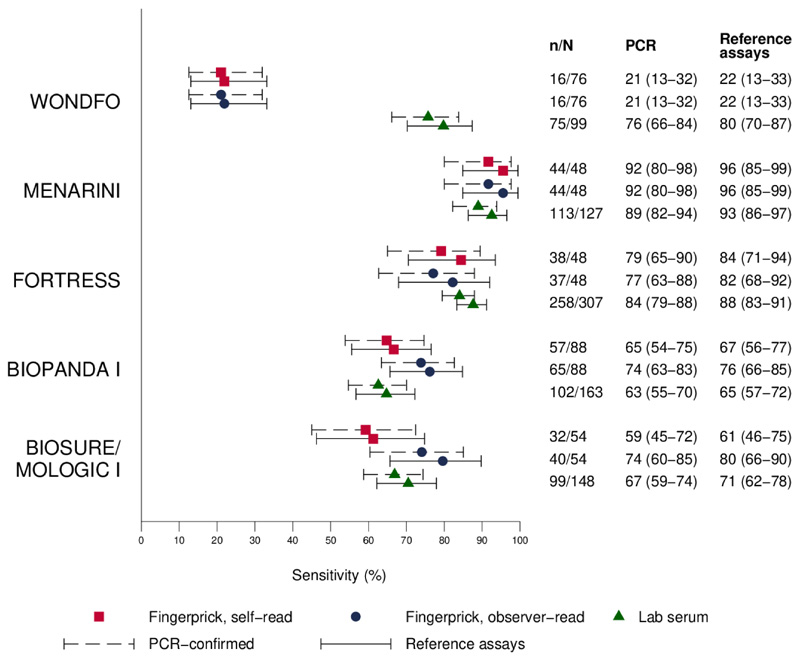

95% (95% CI 92.2% to 97.3%) of the infected cohort had detectable antibodies on at least one ELISA. LFIA sensitivity was variable, but significantly inferior to ELISA in 8 out of 11 assessed. Of LFIAs assessed in both clinic and laboratory, finger-prick self-test sensitivity varied from 21% to 92% versus PCR-confirmed cases and from 22% to 96% versus composite ELISA positives. Concordance between finger-prick and serum testing was at best moderate (kappa 0.56) and, at worst, slight (kappa 0.13). All LFIAs had high specificity (97.2%–99.8%).

Interpretation

LFIA sensitivity and sample concordance is variable, highlighting the importance of evaluations in setting of intended use. This rigorous approach to LFIA evaluation identified a test with high specificity (98.6% (95%CI 97.1% to 99.4%)), moderate sensitivity (84.4% with finger prick (95% CI 70.5% to 93.5%)) and moderate concordance, suitable for seroprevalence surveys.

Introduction

There are currently more commercially available antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 than any other infectious disease. By May 2020, over 200 tests were available or in development.1 Accurate antibody tests are essential to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic at population level, to understand immune response and to assess individuals’ exposure and possible immunity from reinfection with SARS-CoV-2. Serology for national surveillance remains the fourth key pillar of the UK’s national testing response.2

Access to high-throughput laboratory testing to support clinical diagnosis in hospitals is improving. However, the use of serology for large-scale seroprevalence studies is limited by the need to take venous blood and transport it to centralised laboratories, as well as assay costs. Lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs) offer the potential for relatively cheap tests that are easily distributed and can be either self-administered or performed by trained healthcare workers. However, despite manufacturers’ claims of high sensitivity and specificity, reported performance of these assays has been variable3–9 and their use is limited to date.

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) requires that clinical sensitivity and specificity must be determined for each claimed specimen type, and that sample equivalence must be shown.10 For antibody tests intended to determine whether an individual has had the virus, the MHRA recommend a sensitivity >98% (95% CI 96% to 100%) (on a minimum of 200 known positive specimens, collected 20 days or more after symptom onset) and specificity >98% on a minimum 200 known negatives.10 To date, no LFIAs have been approved for use by these criteria. However, LFIAs with lower sensitivity can still play an important role in population sero-prevalence surveys,11 in which individual results are not used to guide behaviour, provided specificity (and positive predictive value) is high. Such tests will need to have established performance characteristics for testing in primary care or community settings, including self-testing.

As part of the REACT (REal Time Assessment of Community Transmission) programme,12 we assessed LFIAs for their suitability for use in large seroprevalence studies. This study addresses the key questions of how well LFIAs perform in people who do not require hospitalisation, and how finger-prick self-testing compares with laboratory testing of serum on LFIAs and ELISA.

Methods

A STARD checklist (of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies) is provided in the online supplementary section.

Patient recruitment and selection of sera

Between 1 and 29 May 2020, adult NHS workers (clinical or non-clinical), who had previously tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR, but not hospitalised, were invited to enrol into a prospective rapid antibody testing study, across four hospitals in two London NHS trusts. Participants were enrolled once they were at least 21 days from the onset of symptoms, or positive swab test (whichever was earlier). Sera for specificity testing were collected prior to August 2019 as part of the Airwaves study13 from police personnel.

Test selection

LFIAs were selected based on manufacturer’s performance data, published data, where available, and the potential for supply to large-scale seroprevalence surveys. Initially, five LFIAs were assessed, with a view to using the highest performing test in a national seroprevalence survey commencing in June 2020 (phase I). After selection of an initial candidate, further evaluation was undertaken of LFIAs to be considered for future seroprevalence surveys (phase II, ongoing). For all LFIAs, sensitivity analysis was conducted on a minimum 100 sera from the assembled cohort. LFIAs with >80% sensitivity underwent further specificity testing, and those with specificity >98% are being evaluated in clinic.

Of tests included in phase I, one detected combined immuno-globulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin (IgG) as a single band, three had separate bands for IgM and IgG, and one detected IgG only. This study set out to determine sensitivity and specificity of tests in detecting IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, at least 21 days from symptom onset. For consistency, in the three kits which had separate IgM and IgG bands, only IgG was counted as a positive result (ie, ‘MG’ or ‘G’ but not ‘M’, distinct from manufacturer guidance).

Study procedure

Each participant performed one of five LFIA self-tests with finger-prick capillary blood, provided a venous blood sample for laboratory analysis, and completed a questionnaire regarding their NHS role and COVID-19 symptoms, onset and duration (see online supplementary table ii: flow of participants). Participants were asked to rate their illness as asymptomatic, mild, moderate or severe, based on its effect on daily life, and record symptoms based on multiple choice tick box response. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and in the supplement.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| All individuals (n=315) | |

|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | |

| Age | 37 (29–47) |

| Female, n (%) | 221 (71) |

| Role, n (%) | |

| Doctor | 111 (36) |

| Nurse or midwife | 114 (37) |

| Other clinical | 51 (17) |

| Non-clinical | 31 (10) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Organ transplant recipient | 1 (0) |

| Diabetes (type I or II) | 7 (2) |

| Heart disease or heart problems | 6 (2) |

| Hypertension | 20 (6) |

| Overweight | 50 (16) |

| Anaemia | 7 (2) |

| Asthma | 33 (11) |

| Other lung condition | 1 (0) |

| Weakened immune | 3 (1) |

| Depression | 14 (4) |

| Anxiety | 23 (7) |

| Psychiatric disorder | 1 (0) |

| No comorbidity | 198 (63) |

| COVID-19 characteristics | |

| Self-assessed disease severity, n (%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 7 (2) |

| Mild | 56 (18) |

| Moderate | 163 (52) |

| Severe, not hospitalised | 87 (28) |

| Duration of symptoms, days | 13 (9–23) |

| Time since symptom onset, days | 44 (35–53) |

Results are median (IQR), unless otherwise stated. Percentages are calculated from non-missing values. Symptom feedback incomplete for two participants.

The LFIA self-tests were performed using instructions specific to each device (see online supplementary table i) observed by a member of the study team. Results were recorded at the times specified in the product insert. Participants were asked to grade intensity of the result band(s) from 0 (negative) to 6 according to a standardised scoring system on a visual guide (see online supplementary figure ii). Invalid tests were repeated. A photograph of the completed test was emailed to the study team.

The first 77 participants enrolled to the study all used the same device. Subsequent participants used different LFIAs according to the study site attended (i.e consecutive allocation). As new LFIAs became available, participants were invited for a second visit to perform an alternative LFIA. A simultaneous venous sample for laboratory analysis was taken at all visits.

To assess concordance, each finger-prick self-test in the clinic was performed with the same participant’s serum in the laboratory. Test evaluations were conducted according to manufacturer’s instructions, by a technician blinded from the clinic result or patient details. Any invalid tests in the laboratory were repeated. Initially, scoring was performed independently by two individuals, but this practice ceased after inter-rater scoring was found to be almost perfect by 7-point categorical score (0–6) (kappa=0.81)14 and perfect on binary outcome (positive/negative) (online supplementary Table 4).

Given uncertainties over the proportion of individuals who develop antibodies with non-hospitalised disease, additional serological testing was performed with two laboratory ELISAs: spike protein ELISA (S-ELISA) and a hybrid spike protein receptor binding domain double antigen bridging assay (hybrid DABA). Both ELISAs were shown to be highly specific. Details of these methodologies and their prior specificity testing are available in the supplementary section. Sensitivity of each LFIA in clinic and laboratory was assessed versus PCR-confirmed cases, versus S-ELISA and versus hybrid DABA.

Sample size

Sample size for individual tests was calculated using exact methods for 90% power and a significance level α=0.05 (one sided). To detect an expected sensitivity of 90% with a minimal acceptable lower limit of 80%, a sample size of 124 was targeted. For specificity, a sample size of 361 is required based on an expected specificity of 98% and a lower limit of 95%.

Performance analysis

The primary outcome was the sensitivity and specificity of each rapid test. For sensitivity, tests were compared against two standards: (1) PCR-confirmed clinical disease (via swab testing) and (2) positivity in patients with either a positive S-ELISA and/or hybrid DABA in the laboratory.

LFIA performance was assessed with (1) finger-prick self-testing (participant interpretation); (2) finger-prick self-testing (trained observer interpretation); and (3) serum in the laboratory. Specificity of LFIAs was evaluated against the known negative samples, with all positives counting as false positives. The analysis included all available data for the relevant outcome and are presented with the corresponding binomial exact 95% CI.

Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) are calculated for a range of population seroprevalence (from 0.1% to 20%). For the purposes of this calculation, we use LFIA sensitivity scores with serum in laboratory (rather than fingerprick) to ensure sample consistency with the prepandemic sera used for specificity analysis.

For comparison of individual test performance between clinic and laboratory, we compare cases where paired results from an individual were available from both settings. We calculate sensitivities and 95% CI and test differences using the McNemar test for dependent groups. Agreement between the testing methods was assessed using the Kappa statistic. Interpretation of kappa values is as follows: <0, poor agreement; 0.00–0.20, slight agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; and >0.8, almost perfect agreement.14

All data were analysed using Stata (V.14.2, StataCorp, Texas, USA), and a p value<0.05 was considered significant.

Patient and public involvement

As part of the REACT programme, there has been extensive input into the study from a patients’ panel, identified through the Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC) of Imperial College and IPSOS/MORI. This has included feedback around study materials, methods, questionnaires and extensive usability testing of LFIAs through patient panels. User-expressed difficulties interpreting results motivated us to investigate agreement between self-reported and clinician-reported results. Usability data from this public outreach will be published in an additional study. Results of the study, once published, will be disseminated to Imperial College Healthcare NHS staff.

Results

We assessed LFIA sensitivity on sera from 276 NHS workers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection at a median 44 days from symptom onset (range 21–100 days). Seventy-two per cent reported no, mild or moderate symptoms, 28% reported severe symptoms and none were hospitalised (Table 1). The most common symptoms described were lethargy (78%), loss of smell (66%), fever (61%), myalgia (61%) and headache (61%) (online supplementary table iii). Less than half reported persistent cough (46%) or dyspnoea (41%). Median symptom duration was 13 days.

Evidence of antibody response was found in 94.5% (95% CI 91.4% to 96.8%) sera assayed using the S-ELISA, 94.8% (95% CI 91.6% to 97.1%) on hybrid DABA, and 95.2% (95% CI 92.2% to 97.3%) using a composite of the two (Table 2). Agreement between the two laboratory ELISAs was very high (online supplementary figure i). Seven of 11 LFIAs assessed with serum detected less than 85% of samples positive on either ELISA (<85% sensitivity vs laboratory standard). Four LFIAs detected >85% positive sera. The most sensitive test identified antibodies in 93% (95% CI 86.3% to 96.5%) of positive samples from composite ELISA testing.

Table 2. Results for all LFIAs analysed.

| Sensitivity |

Specificity |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sera (vs positives on S-ELISA and/or hybrid DABA) |

Finger-prick self-test (vs positives on S-ELISA and/or hybrid DABA) |

Police force sera Nov 2019 (all positives considered false) |

|||||||||

| Lateral flow assay | Sensitivity | 95% CI | n/N | Sensitivity | 95% CI | n/N | Specificity | 95% CI | n= | Invalidity (n) | |

| Phase 1 | W0NDF0(lgM/lgG combined) | 80% | 70.2 to 87.4 | 75/94 | 22% | 13.1 to 33.1 | 16/73 | 99.4% | 98.3 to 99.9 | 497/500 | 0% (0) |

| MENARINI (separate IgM and IgG) | 93% | (86.3 to 96.5 | 112/121 | 96% | 84.9 to 99.5 | 43/45 | 97.8% | 96.1 to 98.9 | 489/500 | 0.6% (3) | |

| FORTRESS (separate IgM and IgG) | 88% | 83.3 to 91.2 | 255/291 | 84% | 70.5 to 93.5 | 38/45 | 98.6% | 97.1 to 99.4 | 493/500 | 0.6% (3) | |

| BIOPANDA 1 (separate IgM and IgG) | 65% | 56.7 to 72.2 | 101/156 | 67% | 55.5 to 76.6 | 56/84 | 99.8% | 98.9to 100.0 | 499/500 | 0% (0) | |

| BIOSURE/MOLOGIC 1 (IgG only) | 71% | 62.2 to 77.9 | 98/139 | 61% | 46.2 to 74.8 | 30/49 | 97.2% | 95.3 to 98.5 | 486/500 | 1.6% (8) | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Phase II | SURE-BIOTECH (separate IgM and IgG) | 68% | 57.3 to 77.1 | 63/93 | |||||||

| BIOSURE/MOLOGIC II (IgG only)* | 48% | 40.8 to 55.9 | 87/180 | ||||||||

| BIOPANDA II (separate IgM and IgG) | 82% | 75.7 to 86.4 | 151/184 | 98.4% | 96.5 to 99.2 | 442/450 | 0% (0) | ||||

| BIOMERICA (separate IgM and IgG) | 81% | 74.7 to 86.4 | 149/184 | 97.8% | 96.1 to 98.9 | 489/500 | 0% (0) | ||||

| SURESCREEN (separate IgM and IgG) | 88% | 81.8 to 91.9 | 161/184 | 99.8% | 98.9 to 100 | 499/500 | 0% (0) | ||||

| ABBOTT (separate IgM and IgG) | 91% | 85.6 to 94.5 | 167/184 | 99.8% | 98.9 to 100 | 499/500 | 0% (0) | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Reference assays | Laboratory test | vs PCR-confirmed cases | |||||||||

| S-ELISA | 94.5% | 91.4 to 96.8 | 293/310 | ||||||||

| RBD hybrid DABA | 94.8% | 91.6 to 97.1 | 274/289 | ||||||||

| Composite ELISA/hybrid DABA positivity | 95.2% | 92.2 to 97.3 | 296/311 | ||||||||

Biosure/Mologic II was tested with 5 μι serum in phase II (in accordance with instructions provided at time). Manufacturer advises test should be performed with 10 μι serum. DABA, Double antigen bridging assay; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; RBD, Receptor binding domain; S-ELISA, spike protein ELISA.

Of the five LFIAs tested in laboratory and clinic, sensitivity of two of the tests was reduced in a clinical setting using fingerprick self-testing, giving positive results for 21.9% (95% CI 13.1% to 33.1%) (80% in laboratory) and 61.2% (95% CI 46.2% to 74.8%) (71% in laboratory) of individuals whose sera tested positive with the ELISAs (Figure 1). To explore whether this discrepancy was due to sample type (serum vs blood), or influenced by test operator (participant vs laboratory technician), we also tested four of the LFIAs with whole blood in laboratory (online supplementary table iv). The least sensitive test was significantly inferior with whole blood (57.1% (95% CI 45.4% to 68.4%)) versus composite of laboratory ELISAs than with serum (79.8% (95% CI 70.2% to 87.4%)), but the other three LFIAs were broadly similar with both whole blood and serum.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity of lateral flow immunoassays with (A) finger-prick (self-read), (B) finger-prick (observer read) and (C) serum in laboratory compared with (1) PCR-confirmed cases or (2) individuals testing positive with at least one of two laboratory assays (spike protein ELISA and hybrid spike protein receptor binding domain double antigen bridging assay).

The two LFIAs that showed higher sensitivity with serum detected 95.6% (95% CI 84.9% to 99.5%) and 84.4% (95% CI 70.5% to 93.5%) composite laboratory ELISA positives from finger-prick self-testing in clinic.

Findings from the matched clinic and laboratory results are presented in Table 3. Concordance between LFIA performance in clinic, with finger prick, and in laboratory, with serum, on the same participants, was variable, with three tests showing ‘moderate’ agreement (kappa 0.41, 0.54, 0.56), according to Landis and Koch interpretation,14 one showing ‘fair’ agreement (kappa 0.34) and the other only ‘slight’ (kappa 0.13) (Table 3). Of the tests performed in the clinic, results reported by participants were consistent with those reported by a trained observer in four out of the five LFIAs. In one LFIA, observer-read positive results were frequently reported as negative by study participants.

Table 3. Matched samples from clinic versus laboratory.

| WONDFO | MENARINI | FORTRESS | BIOPANDA i | BIOSURE/MOLIGIC I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched LFIA results between clinic and laboratory, n | 76 | 47 | 48 | 68 | 44 |

| Days since symptom onset, median (IQR) | 37 (32–47) | 41 (33–47) | 59 (49–69) | 44 (35–54) | 40 (32–49) |

| Sensitivity (%) against reference assays (95% CI) | |||||

| Sensitivity vs PCR confirmed | |||||

| Clinic (fingerprick) | 21.1 (12.5 to 31.9) | 91.5 (79.6 to 97.6) | 79.2 (65.0 to 89.5) | 64.7 (52.2 to 75.9) | 56.8 (41.0 to 71.7) |

| Laboratory (serum) | 73.7 (62.3 to 83.1) | 93.6 (82.5 to 98.7) | 87.5 (74.8 to 95.3) | 75.0 (63.0 to 84.7) | 79.5 (64.7 to 90.2) |

| p<0.001 | p=1.000 | p=0.219 | p=0.167 | p=0.006 | |

| Kappa | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.24) | 0.54 (0.08 to 1.00) | 0.56 (0.25 to 0.86) | 0.34 (0.11 to 0.58) | 0.41 (0.16 to 0.65) |

| Sensitivity (%) vs S-ELISA and/or hybrid DABA | |||||

| Clinic (finger prick) | 21.9 (13.1 to 33.1) | 95.6 (84.9 to 99.5) | 84.4 (70.5 to 93.5) | 67.7 (54.9 to 78.8) | 60.0 (43.3 to 75.1) |

| Laboratory (serum) | 76.7 (65.4 to 85.8) | 95.6 (84.9 to 99.5) | 93.3 (81.7 to 98.6) | 76.9 (64.8 to 86.5) | 85.0 (70.2 to 94.3) |

| p<0.001 | p=1.000 | p=0.219 | p=0.238 | p=0.002 |

Sample is individuals with only matched clinic and laboratory results for the specific LFIAs. 95% CI, 95% binomial exact CI. P v using McNemar’s χ2 test. Kappa is the inter-rater agreement between the self-test result and the serum test result.

hybrid DABA, hybrid spike protein receptor binding domain double antigen bridging assay; S-ELISA, spike protein ELISA.

Specificity was high for all LFIAs assessed (Table 2), ranging from 97.2% to 99.8% in phase I and from 97.8% to 99.8% in phase II. For the purposes of this evaluation, in the LFIAs that had separate IgM and IgG bands, IgM alone was counted as a negative result. Counting IgM alone (without IgG) as a positive result made no difference in performance for most LFIAs, with the exception of the Fortress and Biomerica. In both these tests, specificity was reduced to 96% when IgM counted as positive.

PPV (probability that a positive test result is a true positive) was highest for the LFIAs with highest specificity and fell below 85% at 10% seroprevalence for two of the LFIAs tested in phase I (Menarini and Biosure/Mologic). NPV varied little between tests (online supplementary figure iv).

Any invalid tests were repeated. For one LFIA, 8 out of 508 (1.6%) results were invalid, two tests had 3 out of 503 (0.6%) invalid results, and the remaining six tests had no invalid results on specificity testing (Table 3).

Discussion

LFIAs offer an important tool for widespread community screening of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. They have already been used for large regional and national seroprevalence surveys in the USA and Europe.15–17 However, to allow robust estimates of seroprevalence, a better understanding is needed of (1) the performance of LFIAs in the general population, where most infected patients have not been hospitalised (and may have lower antibody responses associated with asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic infection)18–20; (2) the performance of LFIAs in finger-prick self-testing; and (3) the reliability of LFIA user interpretation.

Specificity of the rapid tests was high. For six (of nine) LFIAs assessed, specificity exceeded 98% (the minimum standard recommended by MHRA for clinical use). All had sufficient specificity to be considered for seroprevalence studies. However, all 11 LFIAs assessed (in phase I and phase II) had lower sensitivity than reported in manufacturers’ instructions, in comparison with either PCR-confirmed cases or laboratory ELISAs.

Lower sensitivity than that reported by manufacturers could be explained by a number of factors. In contrast to previous studies,3,4,7 recruitment focused on non-hospitalised participants, the majority of whom did not have severe symptoms. Antibody responses in this group may be of lower titre.21 Of note, 5% of participants had no detectable antibody on either sensitive ‘in-house’ immunoassay. Therefore, positivity on these assays was used as a reference for comparison. Recruiting patients at least 21 days after symptoms may be expected to improve sensi-tivity.22 Median time from symptoms to recruitment here was 42 days. While it is possible that responses may be waning at this point, we did not see a difference in the mean strength of immune response in the ‘in house’ immunoassays with increasing time since symptom onset (online supplementary figure v). This provides some reassurance that antibody responses may be stable for up to 3 months, although this will be informed by emerging longitudinal data from individual patients.21,23

Instructions for all the kits in this study advise that they are suitable for use with whole blood or serum. Two of the kits additionally recommend finger-prick testing. In general, the sensitivity of tests was similar when comparing results from sera or whole blood in the laboratory with that from finger-prick blood in clinic. However, this was not uniformly the case and one test had significantly superior sensitivity with serum (80%) than with whole blood (57%) or finger prick (22%) (online supplementary table iv). Such sample discordance has also been described in other infections.24,25

Overall, there was good agreement between self-reported results and those reported by an observer. The exception was for one test which differs in its design from the other LFIAs. It has a cylindrical plastic housing surrounding the lateral flow strip within which very faint lines were common and sometimes not reported by participants. Inter-practitioner variation with this kit may have arisin because these results were not routinely read against a white card, which would normally be recommended. The data here support the use of the other tests for self-administration, and potentially others like them, if detailed instructions are provided. However, it should be noted that although many participants were healthcare workers (from a range of areas including both clinical and non-clinical staff), they may not be representative of the general population. Further work is underway to assess the tests with a study group better representing the general population.

It is not possible to generalise these findings to all LFIAs, particularly as manufacturers continue to develop better assays and housings. However, these results emphasise the need to evaluate new tests in the population of intended use and demonstrate that laboratory performance cannot be assumed to be a surrogate for finger-prick testing.

In summary, this study describes a systematic approach to clinical testing of commercial LFIA kits. Based on a combination of kit usability, high specificity (98.6% (95% CI 97.1% to 99.4%)), moderate sensitivity (84% with fingerprick (95% CI 70.5% to 93.5%), 88% with serum (95% CI 83.3% to 91.2%)), high PPV (87% (95% CI 76.9% to 93.5%)), moderate sample concordance (kappa 0.56 (95% CI 0.25% to 0.86%)) and availability for testing at scale, the Fortress test was selected for a further validation study in over 5000 police force personnel (REACT Study 4) and use in a large, nationally representative seroprev-alence study. The REACT seroprevalence study commenced in England in June 2020. Further analysis of additional LFIAs from phase II will be used to inform subsequent rounds of seropreva-lence studies, as test performance continues to improve.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

What is the key question?

-

►

How well do lateral flow immunoassays perform in people who do not require hospitalisation, and how does finger-prick self-testing compare with performance in the laboratory with serum or laboratory-based ELISA?

What is the bottom line?

-

►

Lateral flow assays are highly specific, making many of them suitable for seroprevalence surveys, but their variable sensitivity and sample concordance means they must be evaluated with both sample and operator of intended use to characterise performance.

Why read on?

-

►

We describe a rigorous approach to lateral flow immunoassay evaluation which identified a suitable candidate for national seroprevalence survey and characterised performance in a non-hospitalised population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who volunteered for finger-prick testing to help with this study. We extend our gratitude to MargaretAnne Bevan, Helen Stockmann, Billy Hopkins, Miranda Cowen, Norman Madeja, Nidhi Gandhi, Vaishali Dave, Narvada Jugnee and Chloe Wood, who ran the antibody testing clinics.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre of Imperial College NHS Trust. GC is supported by an NIHR Professorship. WB is the Action Medical Research Professor. AD is an NIHR senior investigator. DA is an Emeritus NIHR Senior Investigator. HW is an NIHR Senior Investigator. RC holds IPR on the hybrid DABA and this work was supported by UKRI/MRC grant (reference is MC_PC_19078). The sponsor is Imperial College London.

Footnotes

Contributors All listed authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclaimer The funders had no role in the production of this manuscript.

Competing interests All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval The study’s conduct and reporting is fully compliant with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. This work was undertaken as part of the REACT 2 study, with ethical approval from South Central–Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee (REC ref: 20/SC/0206; IRAS 283805). Samples for negative controls were taken from the Airwave study approved by North West–Haydock Research Ethics Committee (REC ref: 19/NW/0054).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Anonymised data with results of positive/negative individual tests can be provided on request through contact with study team. Email b.flower@imperial.ac.uk; ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2659-544X.

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ’s website terms and conditions for the duration of the covid-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.

References

- 1.FIND. SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic pipeline. Published 2020. Available: https://www.fnddx.org/covid-19/pipeline/

- 2.Department for Health and Social Care. Coronavirus (COVID-19) scaling up our testing programmes. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fle/878121/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-strategy.pdf.

- 3.Adams E, Ainsworth M, Anand R, et al. Antibody testing for COVID-19: a report from the National COVID scientifc Advisory panel. medRxiv. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15927.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitman JD, Hiatt J, Mowery CT, et al. Test performance evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 serological assays. medRxiv. 2020 2020042520074856. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lassaunière R, Frische A. Evaluation of nine commercial SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. medRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontou PI, Braliou GG, Dimou NL, et al. Antibody tests in detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection: a meta-analysis. Diagnostics. 2020:10. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10050319. Epub ahead of print: 19 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickering S, Betancor G, Galão P, et al. Comparative assessment of multiple COVID-19 serological technologies supports continued evaluation of point-of-care lateral flow assays in hospital and community healthcare settings. medrxiv.org. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asselah T, Lee SS, Yao BB, et al. Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 5 or 6 infection (ENDURANCE-5,6): an open-label, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallett S, Denny S, Patel A, et al. Point-Of-Care serological assays for SARS-CoV-2 in a UK hospital population: potential for enhanced case finding 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85247-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MHRA. Target product profle antibody tests to help determine if people have immunity to SARS-CoV-2. 2020 Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fle/883897/Target_Product_Profle_antibody_tests_to_help_determine_if_people_have_immunity_to_SARS-CoV-2_Version_2.

- 11.Andersson M, Low N, French N, et al. Rapid roll out of SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing- a concern. BMJ. 2020;369:m2420. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.REACT. Real-Time assessment of community transmission (react) study Imperial College London. 2020 Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/research-and-impact/groups/react-study/

- 13.Elliott P, Vergnaud A-C, Singh D, et al. The Airwave health monitoring study of police officers and staff in Great Britain: rationale, design and methods. Environ Res. 2014;134:280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977a;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendavid E, Mulaney B. COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in SANTA Clara County, California. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab010. 2020041420062463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valenti L. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence trends in healthy blood donors during the COVID-19 Milan outbreak. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.2450/2021.0324-20. 2020051120098442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, Pastor-Barriuso R, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE- COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020:31483–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. Epub ahead of print: 18 Jun 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H-Q, Sun B-Q, Fang Z-F, et al. Distinct features of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA response in COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01526-2020. 2001526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan W. Viral kinetics and antibody responses in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 2020032420042382. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long Q-X, Tang X-J, Shi Q-L, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. Epub ahead of print: 18 Jun 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, et al. Antibody tests for identifcation of current and past infection with SARS-CiV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6C doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652. D013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S. Prevalence of IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan - implications for the ability to produce long-lasting protective antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drain PK, Hong T, Krows M, et al. Validation of clinic-based cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay screening in HIV-infected adults in South Africa. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2687. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwyn S, Mitchell A, Dean D, et al. Lateral flow-based antibody testing for Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol Methods. 2016;435:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.