Abstract

Objectives

Globalisation has given medical university students the opportunity to pursue international electives in other countries, enhancing the long-term socialisation of medical professionals. This study identified the long-term effects of international electives on the professional identity formation of medical students.

Design

This is a qualitative study.

Setting

The authors interviewed Japanese medical professionals who had completed their international electives more than 10 years ago, and analysed and interpreted the data using a social constructivism paradigm.

Participants

A total of 23 medical professionals (mean age 36.4 years; range 33–42 years) participated in face-to-face, semistructured in-depth interviews.

Results

During the data analysis, 36 themes related to professional identity formation were identified, and the resulting themes had five primary factors (perspective transformation, career design, self-development, diversity of values and leadership). It was concluded that international electives for medical students could promote reflective self-relativisation and contribute to medical professional identity formation. Additionally, such electives can encourage pursuing a specialisation and academic or non-academic work abroad. International electives for medical students could contribute to medical professional identity formation on the basis of cross-cultural understanding.

Conclusions

This study addressed a number of issues regarding the long-term impact of international elective experiences in various countries on the professional identity formation of Japanese medical professionals. This study offers some guidance to mentors conducting international electives and provides useful information for professional identity formation development in medical professionals.

Keywords: qualitative research, medical education & training, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study identified the long-term effects of international electives on the professional identity formation of medical students.

Qualitative data were collected from 23 medical professionals who completed their international electives more than 10 years ago and were analysed using the thematic analysis method.

The study was limited by the focus on only Japanese medical professionals whose professional identity formation was affected by their innate cultural values and social norms.

Further investigation of how medical professionals adopt their experiences to their environments is required.

Introduction

Globalisation has given medical university students the opportunity to pursue international electives in other countries,1–3 which can enhance the long-term socialisation of medical professionals. Studies have found that international electives may have a transformative learning potential4 5 as they immerse medical students in cross-cultural settings that can strengthen and challenge their professional identities.6 However, these studies have not clarified the long-term contributions to medical professional socialisation. Therefore, this study explored the long-term effects of international electives for medical students on medical professional socialisation from a professional identity formation (PIF) perspective.

As international electives for medical students have been found to contribute to medical education internationalisation by enhancing global health competencies and encouraging global citizenship,7 8 they are an important part of undergraduate medical training to prepare students for the globalised world.5 International electives for medical students enhance the knowledge of medical students about areas and issues outside the traditional medical school curricula, such as current research, global clinical practices, healthcare systems around the world and cultural competencies, which often influence the students’ career choices.6 9 10 Previous studies have found that international electives for medical students increase the probability of students choosing primary care specialties (eg, family medicine, internal medicine and paediatrics) or public health as their career paths.2 11 However, through international electives, it is important to understand how students learn regardless of whether they choose to follow primary care specialties.12 International electives for medical students give medical students an opportunity to reflect on their experiences by highlighting their personal and professional identities and allowing them to closely examine the health outcomes in their own countries.10 13 Several participants who have reflected on their undergraduate careers have stated that their elective experiences were transformative, served to refresh the values that were underpinning their initial motivations to enter the profession5 and led to valuable insights into the potential congruence of their personal and professional identities.14 As mentioned in the PIF framework by Cruess et al15 16, socialisation is useful when seeking to understand the transformative learning of international electives for medical students as medical students are often in a formative state and thus more susceptible to the influences of their cultural backgrounds and learning environments.17 Socialisation and identity formation have been found to be strongly connected.18 Using narrative reflective reports, Sawatsky et al4 identified some transformative learning components—disorienting experiences, emotional responses, critical reflection, perspective changes and a commitment to future action—and clarified how these were related to professional identity transformations for residents participating in international electives. However, Sawatsky et al’s4 study did not explain these relationships in undergraduate settings or clarify the long-term contributions to medical professional socialisation. As educational activities that foster a deep PIF-associated transformation, such as international electives, should be long term and cumulative in nature,19 this study focused on these aspects.

In western education environments, international electives for medical students are often conducted in and focused on low-income and middle-income countries. However, in Asian countries, including Japan, these electives are generally conducted and focused on developed countries. A National Survey in Japan found that a majority of Japanese exchange students travelled to both western and Asian countries, with approximately 70% choosing to study in Europe and North America, reflecting the desire of Japanese students to acquire medical knowledge or experiences through the English language.3 20 However, 40% of the UK’s medical students chose low-income and middle-income countries and approximately one-third of medical students in the USA, Canada and Germany selected low-income and middle-income countries to complete their international electives before graduation.21 22

Professional identity and socialisation

Becoming a physician is challenging and transformative23; therefore, medical education needs to be responsive to the changes in students’ professional identities from their experiences and from society.24 Cruess et al17 defined professional identity as ‘a representation of self, achieved in stages over time during which the characteristics, values and norms of the medical profession are internalised, resulting in an individual thinking, acting and feeling like a physician,’ and Holden et al19 recommended professional identity development to be integrated with core medical knowledge, skills and attitudes. Hence, professional identity is developed through socialisation from a layperson to a professional, and it is unique to each learning environment.15 International electives for medical students provide them with unique learning experiences that have transformative components assisting in professional and personal socialisation. Jarvis-Selinger et al18 defined PIF as ‘an adaptive developmental process that happens simultaneously (1) at the level of the individual, which involves the psychological development of the person and (2) at the collective level.’ Studies have found that role models, mentors and experiential learning, in both clinical and nonclinical situations, were the most powerful PIF factors.15 Therefore, international electives are expected to be part of a medical student’s long-term, cumulative education that enacts the deep transformations associated with PIF.19 Frost and Regehr23 suggested that the implications arising from the different professional identities of medical students needed to be explored.

Research question

Using a qualitative method, this study examined the contribution of international electives for medical students conducted in various countries, mainly high-income counties, to the PIF of Japanese medical professionals, with the primary objective being to assess the relationship between the electives and PIF to clarify their long-term effects. Therefore, the research question driving this qualitative research was ‘How do international electives for medical students contribute to the PIF of Japanese medical professionals?’ It is expected that the study findings could guide mentors when conducting international electives for medical students and provide useful information to foster PIF development in medical professionals.

Method

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research recommendations.25 This study was based on the constructivist paradigm stating that human knowledge is not discovered but socially constructed.26 The qualitative data were collected from 23 face-to-face, semistructured in-depth interviews and 16 narrative reflective reports on international electives for medical students written by the study participants to clarify the relationships between these experiences and PIF pedagogy. All of the interview data and reflective reports were inductively analysed and integrated through the data analysis. Thematic analysis was employed to elicit the subjective meanings, which involved generative coding and theoretical interpretations by several researchers. The authors were familiar with international electives because we have participated in postinternational electives presentations by medical students and continue to engage with medical students participating in international electives through teaching practices and mentoring.

Setting

The National Survey of Japan reported that 790 medical students in 2012 and 1069 medical students in 2013 were involved in clinical clerkships or short-term study abroad programmes,3 which was approximately 2% of all Japanese medical students. The University of Tokyo’s international electives for medical students have been formal electives since 2001 and are taken by approximately 3% of the university’s medical students each year, which is considered higher than average in Japan. Similar to the national statistics results, a majority of the university’s exchange students choose to travel to western countries, with approximately 60% choosing to study in Europe and North America, every year. Although more than half of the students opt to complete their electives in the settings available to them through formal programmes offered by the institutions, some students choose to complete their electives in their own choices. As the international elective content is different at various overseas host institutions, they are decided through direct communication between the organisation and the undergraduate student. Regarding financial support, only some students with excellent grades were offered scholarships.

Participants

To understand the long-term effects of such electives, the participants in this study were University of Tokyo’s medical professionals who had been graduated for more than 10 years prior to this study, after completing their international electives. Of the viable participants, all are licensed and experienced medical professionals at a variety of institutions, including university and community hospitals, research centres, medical companies and the Ministry of Health. From 2001 to 2009, 133 University of Tokyo undergraduate students completed international electives, and 70 contactable medical professionals who had completed their international electives were invited via email to participate in the study. Overall, 23 participants (mean age 36.4 years; range 33–42 years) agreed, all of whom had taken the international electives programme more than 10 years ago. Of the 23 participant profiles given in table 1, a majority chose to go to the USA, with only a few choosing other countries.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the research participants

| No | Sex | Specialty | Host country | Type of electives |

| 1 | M | Internal medicine | USA (NY), UK | Clinical |

| 2 | F | Rheumatology | USA (WA) | Clinical |

| 3 | F | Neurology | USA (OR) | Clinical |

| 4 | F | Paediatrics | USA (PA) | Research |

| 5 | M | Emergency | USA (OR), Brazil | Clinical |

| 6 | M | Endocrinology | USA (CA) | Clinical |

| 7 | M | Intensive care | USA (OH) | Clinical |

| 8 | M | Gastrointestinal surgery | USA (OR) | Clinical |

| 9 | M | Thoracic surgery | US (PA) | Clinical |

| 10 | M | Endocrinology | USA (PA) | Research |

| 11 | M | Haematology | USA (OR) | Clinical |

| 12 | M | Emergency | India, Nepal | Clinical |

| 13 | M | Orthopaedics | USA (MI) | Clinical |

| 14 | M | Emergency | USA (PA) | Research |

| 15 | M | Respiratory | USA (MA) | Clinical |

| 16 | M | Neurology | USA (PA) | Research |

| 17 | M | Radiology | Thailand | Clinical |

| 18 | M | Neurology | USA (MA, MN) | Clinical, Research |

| 19 | M | Health policy | USA (NY, OR) | Clinical |

| 20 | M | Cardiac surgery | Australia | Clinical |

| 21 | M | Ophthalmology | USA (CA) | Clinical |

| 22 | F | Physiology | USA (PA) | Clinical |

| 23 | F | Surgery | India | Clinical |

F, female; M, male.

Patient and public involvement

No patients involved.

Data collection

The authors analysed narrative reflective reports on the international electives for medical students that had been written by the study participants more than 10 years ago. Narrative reflective reports on the international electives for medical students were instructed for each student to submit immediately after completing the international electives. In this report, the students were asked to describe what kind of training they had received in their field as well as what their feelings and struggles through their actual experience and how they interacted with the local medical students. Moreover, the reports were shared with not only the faculty but also other medical students so that they could view it with each other. These reports on international electives for medical students were originally written to take undergraduate students beyond global health facts, as a self-reflective learning process emphasising transnational competence and heightening their empathy for humanity underlying global health issues.27 Therefore, they were considered useful in assessing the existing and potential PIF pedagogy28 and helpful in understanding the long-term contributions of the international electives for medical students on the socialisation of the study participants. However, not all of the reports that were reflective of the medical students’ narrative of the international electives for them as written by the study participants existed, and only 16 reports reflective of the narrative were viewable. The reason why some reflections were excluded in this data collection is simply because those reports did not exist. Open-ended data were also collected, using an audio recorder, from face-to-face, semistructured in-depth interviews, wherein the participants’ feelings and beliefs were explored.29 Interviews were conducted by the first author (MH), which lasted 40–80 min, at the participant’s place of clinical practice between December 2018 and March 2019. All of the interviews were conducted in Japanese. Total recorded data comprised 1077 min of recording. An interview guide (see box 1) was used to clarify how the participants viewed their experiences and how those experiences had contributed to their PIF. The authors agreed that the interview guide was suited to the research purpose; therefore, it was not changed. However, the interviews were flexible so that the participants could take the discussion in any direction. The recorded data were transcribed verbatim by the authors immediately after each interview.

Box 1. Interview guide.

What is your specialty, experience (number of years) and board certification?

Please describe the medical services you usually provide.

What have been your major medical experiences so far?

Describe your international elective experiences and provide details.

Why did you choose to study international electives for medical students?

What are your personal impressions of the international electives for medical students?

How did the impressive episode (answer 6) impact your own medical treatment (attitudes towards medical practice or work) and career development?

What impact did your international electives for medical students have on your professional development? Why do you think so?

Ethics

Ethical concerns included maintaining confidentiality of the sensitive information revealed in the interviews and reflective reports. The participants were informed of the study’s scope and nature, and all of them provided written consent. They were also informed that all data were confidential and that the given consent could be withdrawn at any time.

Data analysis

All of the interview data and reflective reports were analysed and integrated through the data analysis. The data were analysed using the thematic analysis method, which involved generative coding and theorising to identify instances in the data set that were similar in concept.30 31 Data analysis followed an inductive approach where the data are allowed to speak for themselves by the emergence of conceptual categories and descriptive themes. Although the research question was partly theory driven, the researchers initially conducted a primary level thematic analysis to determine themes. After the researchers found the themes and following further team discussion, we re-examined the literature to identify the conceptual perspective. The first and second authors (MH and DS, respectively) were formally trained in using NVivo V.11 for Windows (QSR International, Australia, a computer software program to support the analysis of qualitative data) and conducted all the analysis steps, including the reading and rereading of the narratives until the researchers found the themes and categorising the data from a constructivist perspective. The themes were categorised into main and subcategories and were then tabulated using NVivo V.11 to identify the theme frequencies in the interviews and reports. After the data collection and analyses, the study authors agreed that theoretical saturation had been reached as there were no new themes emerging in the data set, and a complete understanding of the identified concepts had been achieved. Member checking was conducted twice by the research participants after the interviews and analyses to confirm that there is no difference in interpretation and that it is not contrary to the intended content.

Results

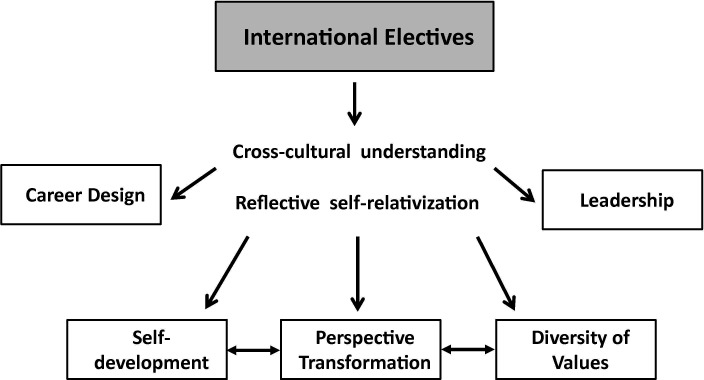

From the thematic analysis of the interviews and reports, 36 emergent themes were identified, several of which were related to PIF. The resulting themes had five primary factors: perspective transformation, career design, self-development, diversity of values and leadership (see box 2). International electives for medical students often lead to specialisations and further academic or non-academic work abroad. Although the contents of international electives for medical students were different between low-income and middle-income countries and developed countries, they were common in that international electives for medical students could promote reflective self-relativisation and contribute to PIF on the basis of the idea of cross-cultural understanding (figure 1). It also became clear that the themes of perspective transformation, self-development and diversity of values showed a linkage between the themes.

Box 2. Emergent themes.

Perspective transformation (17/23)

Self-relativisation (14/23), wide perspective (10/23), contribution to others (8/23), empathy (5/23), self-transformation (3/23).

Career design (16/23).

Pursuit of interest (13/23), right of choice (10/23), role model (10/23), mindset (7/23), work–life balance (1/23), career support (1/23), insufficient information sharing (1/23).

Self-development (17/23)

Cross-boundary experiences (9/23), motivation (8/23), self-reliance (7/23), outcomes (5/23), open mind (4/23), resistance to egoism (1/23).

Diversity of values (14/23)

Cross-cultural understanding (11/23), culture shock (10/23), work style (6/23), acceptance of various values (3/23), globalisation (2/23), flexibility (1/23).

Leadership (14/23)

Decision making (9/23), systems thinking (6/23), objective thinking (4/23), critical thinking (3/23), resilience (3/23), Responsibility (2/23), uncertainty (2/23).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the socialisation process. International electives for medical students could promote reflective self-relativisation and contribute to PIF on the basis of the idea of cross-cultural understanding. Five primary themes were gained from the international elective experiences. The themes of perspective transformation, self-development and diversity of values showed a linkage between the themes. PIF, professional identity formation.

Perspective transformation

Although it was difficult for most participants to specifically describe the international electives’ contents, most commented on the thinking that they had acquired, with the impressions gained being the origins for their own perspective transformations as medical professionals.

Before international electives, I had the perception that surgeons were superior than internists. However, when I met an internist during my international electives in the U.S. who systematically assessed the whole body while carefully questioning and examining the body, my perception that surgeons were superior to them changed markedly. (R7 Male—US—Clinical: Report)

In the past, there were many participants who chose a specialty that was different from what they had hoped for at the time of international electives for medical students. However, they went through a process of reflecting on their experience of international electives when pursuing their own interests. Most participants also believed that the international electives promoted self-relativisation and assisted in their identity development as medical professionals.

It was very striking to me that about half of the patients who see the ER are uninsured. On the other hand, I was able to see how doctors over-test and treat to avoid lawsuits…It was a good experience to realize the position of the Japanese healthcare system by experiencing a different healthcare environment than Japan. (R19 Male—US—Clinical: Report)

After graduating, I became interested in health care policy, and now I am running a company with a vision to create a world where all people can live and die with conviction…I think this is a good opportunity to reevaluate myself. When training at university hospitals and affiliated hospitals, because these organizations are all very similar, there are few differences, so we don’t think about what might be good or bad, or what might be incorrect. I think that this could be an extremely useful opportunity for reevaluation. (R19 Male—US—Clinical: Interview)

Career design

Most participants had continued their careers in Japan but believed that their experiences abroad had some impact on their mindset and work–life balance.

What I saw during my short one month stay was a very small part of the U.S., but I felt that even if I had preconceived notions, I needed to rethink those preconceived notions based on what I had actually experienced. (R3 Female—US—Clinical: Report)

I’m going to the US next year as a postdoctoral researcher…When I think about what it was like when I had the opportunity to go to the U.S. as a medical trainee, this may seem a little vague, but this is the image I was able to give—with my experience at that time, it’s not that the knowledge I learned there was of direct use, but having gone to the U.S. as a medical student was extremely useful to me in terms of planning my own life. (R3 Female—US—Clinical: Interview)

The role models the participants encountered during their international electives for medical students assisted them in developing their careers and pursuing their own interests regardless of whether they chose to follow primary care specialties or opted to work in their countries of origin or abroad.

I am interested in dementia, and during the international electives, I worked with researchers in the field to experiment at a specialized research facility in the U.S. I was struck by the fact that the specialty is extremely fragmented, and even in the same area, there is little involvement in diseases outside of their own specialty. (R18 Male—US—Clinical / Research: Report)

After completing international electives, I wanted to pursue more specialized research in dementia and kept in touch with the mentors who had taught me specialized skills during my practice. I am currently conducting research in this field in the U.S., and the professors are still my direct mentors…Through my research, new therapeutics have been developed and are beginning to be used in clinical practice, so I think I can give back my knowledge in this field by adapting such a process when I return to Japan. (R18 Male—US—Clinical/Research: Interview)

Self-development

The participants said that their experiences of having to adjust to their host country and their elective content by themselves and travelling to their international electives had contributed to their motivation and future independence and had affected their educational behaviour in clinical situations.

Since the hospital had no partnership with the university, I had to do all the preparations myself, and the preparations were more difficult than I expected. It was also my first time to go to a developing country, so I was very busy just before my trip, buying insurance and getting vaccinations…When I returned home, I realized the importance of water and electricity, and how safe Japan is. (R12 Male—Nepal—Clinical: Report)

Through the experience of international electives, I learned the importance of trying anything without fear of failure. Although I am now working in a different department than the one I trained in at the time, I am actively working with patients from a variety of social and economic backgrounds in a multidisciplinary approach. (R12 Male—Nepal—Clinical: Interview)

Throughout their international elective experiences, the medical professionals could not only relativise the environment wherein they had been placed but were also forced to think more deeply about their own strengths. Therefore, the international electives for medical students enhanced the participants’ future self-development.

I was interested in treating congenital diseases, so I went to a lab that was doing gene therapy for hemophilia and had already gone through several trials. I was attracted to the work of the doctors who successfully combined both clinical and research, including unique consultation methods, genetic testing and post-diagnosis follow-up, and feedback to research. (R4 Female—US—Research: Report)

In my current workplace, I am a researcher conducting epidemiological studies on child development. When I grow up, I lived in the U.S. due to my parents’ work…For me in particular, I was raised over there, so I came back to Japan thinking that I could have become like them if I had stayed there. Well, I had an image of who I desired to be when I was there and the real figure of who I am today having come back to Japan.…There was a real sense that clinical training in U.S. was superior, which I wanted to fight against, thinking that we had to somehow do our best in Japan as well. (R4 Female—US—Research: Interview)

Diversity of values

Participants recognised not only the diversity of values they gained from their cross-cultural experiences but were also able to use these experiences when treating patients from other countries. Further, regardless of their specialties, they sought to imagine the patient’s background and religious views when conducting their clinical practice.

All in all, I would say that going to Brazil had a significant effect on me, but I cannot go so far as say that I would force this on Japanese people, or that I would impose my value system, which shifted slightly as a result of my time in Brazil, on Japan….I think I have become better able to respond to patients that have various views and values about life and death. (R5 Male—US/Brazil—Clinical: Interview)

Through international electives, the participants believed that their experience assisted in their identity development as medical professionals and that it contributed to their interpretive and tolerant attitude toward patients and colleagues.

What doctors take for granted and what nurses take for granted are not the same thing. I think there’s a parallel between what the Japanese take for granted and what Americans take for granted. It’s probably the same process of meeting with people who have different ways of thinking so that they can rub together and understand each other’s thoughts. (R6 Male—US—Clinical: Interview)

Leadership

The international elective experiences urged the participants to be more conscious about goal-setting and policy decision making in organisations and gave them a better understanding of their own work environments and of how the working environment knowledge strengthened their awareness of target setting and development.

I decided on the content of my international electives through negotiations with the host laboratory, but I felt that the content could be changed as much as I wanted, depending on my sense of purpose. On the other hand, the U.S. has a system in place that allows researchers to devote themselves to their research, but I found it difficult to bring that to Japan. (R14 Male—US—Research: Report)

I am managing several projects while developing a new medical system that I have been interested in since my electives…I am currently involved in building a rapid response system for the hospital’s needs in case of a patient’s sudden change…Of course, each person’s efforts are important, but I work based on the idea that a system that can provide high quality medical care at all times is important. (R14 Male—US—Research: Interview)

After international elective experiences, participants continued to self-evaluate their own leadership concept and considered the medical approach for the delegation of authority according to their own situation.

I learned the importance of management through my electives in the U.S.…I am now working in policy-related work at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare after leaving my clinical work…I am involved in health policy practice while working with medical institutions, and I feel that my experience in overseas training is helping me to focus on the decision-making process. (R7 Male—US—Clinical: Interview)

Differences in training content and participant characteristics

The participants’ characteristics in this study included differences in training location (19 from high-income countries and five from low-income to middle-income countries), differences in training content (18 from clinical and 5 from research) and differences in gender ratios (18 males and 5 females). As described in the Methods section, the place and content of the training were not simply chosen by the students themselves but were also influenced by institutional partnerships; however, through the data analysis, it was possible to identify some differences.

First, when comparing training in high-income countries with training in low-income to middle-income countries, the theme of ‘diversity of values’ was found throughout the training in low-income to middle-income countries.

Through international electives, I was able to conduct training in two countries, Brazil and the U.S. In Brazil, I experienced a very different culture, nationality, and practice than in Japan. On the other hand, during my electives in the U.S., I experienced a variety of patients in the emergency department, but I didn’t feel that much of a difference with Japan. (R5 Male—US/Brazil—Clinical: Report)

It was also suggested that training in low-income to middle-income countries may have made them aware of the presence of socially vulnerable people and their own social responsibilities, and motivated them to work in the international health field in the future.

I am mainly involved in the international medical support department at my current hospital, where I deal with a variety of foreign patients…I think about medical care and support based on the patient’s background. In Japan, in particular, if a person comes from a developing country, even if they have a working background in Japan and we’re in Japan, they still have a different cultural background, and it good to understand that this is still true while they are living here. (R23 Female—India—Clinical: Interview)

However, the majority of the research participants who experienced research-based electives tended to pursue their own interests and expertise and to continue their careers as researchers in the future.

I was very curious about how mental illness can be studied. It was very interesting that a foreign researcher reported a decrease in the number of dendritic spines in the frontal lobe of schizophrenia, so I wanted to do an international research elective…After I returned to Japan, I joined the classroom of a teacher who is still researching in this field, and now I am also mentoring graduate students as a lecturer. (R16 Male—US—Research: Interview)

Finally, the number of female participants was not as high, but both themes, work–life balance and career support, were unique themes drawn only from female participants.

Discussions

Several constituent elements related to PIF were gained from the international elective experiences. It was evident that the experiences promoted reflective self-relativisation, which contributed to the participants’ identity formation as medical professionals. Studies have shown the potential benefits of international electives for medical students in enhancing both professional and personal development, and building transferable skills from working with people from culturally, linguistically and socioeconomically diverse backgrounds.5 The results of this study contribute to the extant research because of its findings on the long-term influences on PIF from the perspective of international elective experiences. Previous studies have found that international electives for medical students increased the probability of students choosing primary care specialties or public health as their future career paths.2 11 This study uncovered that there were additional long-term career influences regardless of whether the participants followed primary care specialties.

Cruess et al16 indicated that people who went through a socialisation process with only partially developed identities emerged with enhanced personal and professional identities. PIF is a formative development continuum that instils professional values and a sense of being a medical professional. In this study, several factors were found that related to the contribution of international electives for medical students to medical professional socialisation. As the previous study15 has shown, the study results indicated that the presence of a mentor or role model was one of the most important factors as a long-term correlation with what medical professionals considered to their own personal development and who they are 10 years later. The results also indicated that the reflective self-relativisation gained from the international electives was the basis for the medical professionals’ perspective transformations. A previous study found that PIF and socialisation required a reflective process and that individual experiences allowed for the development of ‘their own stories by which to love doctors’ through this self-reflection.24 Therefore, it was concluded that the international elective experiences provided opportunities to medical professionals to not only advance their PIF processes but also reflect on their underlying identities. Furthermore, Cruess et al16 also pointed out that every person’s journey from layperson to professional was unique and that each learning environment had its own characteristics and culture. In this study, the medical professionals who had undertaken international electives not only recognised the diversity of values through their cross-cultural experiences but also gained a greater understanding for patients with different backgrounds.

The findings in this study had important parallels with earlier studies. Previous studies have found that medical professionals need to acquire cultural sensitivity as part of becoming and being a professional.32 When the students become medical professionals and the medical professionals make transitions, being culturally competent means being able to incorporate those views into day-to-day practices.33 As indicated in the results, the cultural sensitivity gained through international electives has led to a different insight into the members of their community. The international electives provided medical students with the opportunities to gain cross-cultural understanding on their PIF journey, which over the long-term contributed to their development of appropriate empathic responses. Gosselin et al34 proposed that medical education researchers should reconsider their assumptions and discourses about the dynamic relationships between culture, globalisation and medical education. Professional identity is also a part of a wider social identity that varies depending on the country of origin and cultural background.33 Monrouxe35 showed that cultural differences could be explained by considering the wider culture inhabited by the medical professionals. Although the international electives for medical students generally run from only 1 to 3 months, based on the previous results, the international electives for medical students in Asian countries could have a substantial impact on the medical students’ socialisation. This is because medical students in Japan are in a learning environment with fewer immigrants than there are in learning environments in other developed countries. As they do not have much experience in deep communication with people from other countries, we thought that the various experiences they had during their international electives would be important opportunities for them to not only acquire career and medical knowledge and skills but also grow as human beings. That would be significant. As for the uniqueness of Japanese educational culture, it has also been indicated that there is an internalisation of ‘hansei’ (introspection) or ‘kaizen’ (change for the better), which is a characteristic of Asian culture.36 37 We believe that when medical students transfer the concepts they have learnt through their international electives to the process of socialisation, a characteristic of reflection occurs at the individual level. The results indicate that a similar process of change in understanding in the medical professionals’ community after their international electives is occurring in Japanese culture.

However, overall, individual PIF development through international electives for medical students in other cultures would need to be more comprehensively studied to assess the transferability of these results. A limitation of this study was that only Japanese medical professionals who had graduated from the University of Tokyo were included, which means that their PIF was affected by their innate cultural values and social norms. Because there are cultural differences between western models and other cultures that do not entirely focus on the individual and possess a more collective culture,33 there are wide differences as to the appropriateness of some professional attributes,35 which means that it is difficult to make generalised statements without knowledge of the individual PIF development in other cultures. However, based on the emergent themes in this study, it is possible that these types of experiences in other cultures would yield similar findings such as perspective transformations, self-development and leadership. Another limitation of this study was that the focus was on medical professionals who were already specialised (mean clinical experience duration was 11.9 years). As identity formation continues throughout the medical professional’s career,18 identities are never fixed.38 Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the socialisation gained from international electives in a younger generation, such as undergraduate students and residents. Finally, the problems that arise from the activities of participants are not clarified in this study. Although we identified the contribution of the international electives to the socialisation process as an outcome, the experiences that the participants gain from their work are complex. Therefore, further investigation of how the medical professionals adopted their experiences in their environments would be required.

Conclusion

This study clarified a number of issues regarding the long-term impact of international elective experiences in various countries on the socialisation of Japanese medical professionals. It was found that these experiences promote reflective self-relativisation and contribute to PIF on the basis of the idea of cross-cultural understanding. The results of this study contribute to the extant research because of their findings on the long-term influences of PIF from the perspective of international elective experiences. It is hoped that this study offers some guidance to mentors conducting international electives for medical students and provides useful information for PIF development in medical professionals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who gave their time and participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH was the principal investigator for this study, who conducted the interviews and authored the paper. KN contributed to the design of this study. DS analysed and coded all data along with MH. ME checked the results, advised edits and approved for public release. All authors have agreed with the final version of this paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo approved this study (2018001NI-(1)).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Harmer A, Lee K, Petty N. Global health education in the United Kingdom: a review of university undergraduate and postgraduate programmes and courses. Public Health 2015;129:797–809. 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan OA, Guerrant R, Sanders J, et al. Global health education in U.S. medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:3. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T, Nishigori H. National survey of international electives for global health in undergraduate medical education in Japan, 2011-2014. Nagoya J Med Sci 2018;80:79–90. 10.18999/nagjms.80.1.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawatsky AP, Nordhues HC, Merry SP, et al. Transformative learning and professional identity formation during international health electives: a qualitative study using grounded theory. Acad Med 2018;93:1381–90. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lumb A, Murdoch-Eaton D. Electives in undergraduate medical education: AMEE guide No. 88. Med Teach 2014;36:557–72. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.907887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramakrishna J, Valani R, Sriharan A, et al. Design and pilot implementation of an evaluation tool assessing professionalism, communication and collaboration during a unique global health elective. Med Confl Surviv 2014;30:56–65. 10.1080/13623699.2014.874088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murdoch-Eaton D, Green A. The contribution and challenges of electives in the development of social accountability in medical students. Med Teach 2011;33:643–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stys D, Hopman W, Carpenter J. What is the value of global health electives during medical school? Med Teach 2013;35:209–18. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neel AF, AlAhmari LS, Alanazi RA, et al. Medical students’ perception of international health electives in the undergraduate medical curriculum at the College of medicine, King Saud university. Adv Med Educ Pract 2018;9:811–7. 10.2147/AMEP.S173023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherniak WA, Drain PK, Brewer TF. Educational objectives for international medical electives: a literature review. Acad Med 2013;88:1778–81. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a6a7ce [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffrey J, Dumont RA, Kim GY, et al. Effects of international health electives on medical student learning and career choice: results of a systematic literature review. Fam Med 2011;43:21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, et al. I came, I saw, I reflected: a qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Med Teach 2009;31:e196–201. 10.1080/01421590802516764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender A, Walker P. The obligation of debriefing in global health education. Med Teach 2013;35:e1027–34. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.733449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach 2012;34:e641–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach 2019;41:641–9. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med 2015;90:718–25. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med 2014;89:1446–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med 2012;87:1185–90. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden MD, Buck E, Luk J, et al. Professional identity formation: creating a longitudinal framework through time (transformation in medical education). Acad Med 2015;90:761–7. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishigori H, Takahashi O, Sugimoto N, et al. A national survey of international electives for medical students in Japan: 2009-2010. Med Teach 2012;34:71–3. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.638014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda JJ, Yudkin JS, Willott C. International health electives: four years of experience. Travel Med Infect Dis 2005;3:133–41. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowson M, Smith A, Hughes R, et al. The evolution of global health teaching in undergraduate medical curricula. Global Health 2012;8:35. 10.1186/1744-8603-8-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost HD, Regehr G. “I am a doctor”: negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Acad Med 2013;88:1570–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a34b05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, et al. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med 2013;25:369–73. 10.1080/10401334.2013.827968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann K, MacLeod A. Constructivism: learning theories and approaches to research : Cleland J, Durning SJ, Researching medical education. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015: 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lencucha R. A research-based narrative assignment for global health education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2014;19:129–42. 10.1007/s10459-013-9446-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wald HS, Anthony D, Hutchinson TA, et al. Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Acad Med 2015;90:753–60. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health 2019;7:e000057. 10.1136/fmch-2018-000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryman A. Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford university press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleland JA. The qualitative orientation in medical education research. Korean J Med Educ 2017;29:61–71. 10.3946/kjme.2017.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Schalkwyk SC, Bezuidenhout J, De Villiers MR. Understanding rural clinical learning spaces: being and becoming a doctor. Med Teach 2015;37:589–94. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.956064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKimm J, Wilkinson T. “Doctors on the move”: exploring professionalism in the light of cultural transitions. Med Teach 2015;37:837–43. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1044953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gosselin K, Norris JL, Ho M-J. Beyond homogenization discourse: reconsidering the cultural consequences of globalized medical education. Med Teach 2016;38:691–9. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1105941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monrouxe LV. Theoretical insights into the nature and nurture of professional identities : Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, Teaching medical professionalism: supporting the development of a professional identity. 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishigori H, Sriruksa K. Asian perspectives for reflection. Med Teach 2011;33:580–1. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saiki T, Imafuku R, Suzuki Y, et al. The truth lies somewhere in the middle: swinging between globalization and regionalization of medical education in Japan. Med Teach 2017;39:1016–22. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1359407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lockyer J, de Groot J, Silver I. Professional identity formation, the practicing physician, and continuing professional development : Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, Teaching medical professionalism: supporting the development of a professional identity. 2nd edn Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016: 186–200. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.