Abstract

Objective

To conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (NHS) comparing ixekizumab versus secukinumab.

Design

A Markov model with a lifetime horizon and monthly cycles was developed based on the York model. Four health states were included: a biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) induction period of 12 or 16 weeks, maintenance therapy, best supportive care (BSC) and death. Treatment response was assessed based on both Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC) and ≥90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score (PASI90). At the end of the induction period, responders transitioned to maintenance therapy. Non-responders and patients who discontinued maintenance therapy transitioned to BSC. Clinical efficacy data were derived from a network meta-analysis. Health utilities were generated by applying a regression analysis to Psoriasis Area Severity Index and Health Assessment Questionnaire‒Disability Index scores collected in the ixekizumab SPIRIT studies. Results were subject to extensive sensitivity and scenario analysis.

Setting

Spanish NHS.

Participants

A hypothetical cohort of bDMARD-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis was modelled.

Interventions

Ixekizumab and secukinumab.

Results

Ixekizumab performed favourably over secukinumab in the base-case analysis, although cost savings and quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gains were modest. Total costs were €153 901 compared with €156 559 for secukinumab (difference −€2658). Total QALYs were 9.175 vs 9.082 (difference 0.093). Base-case results were most sensitive to the annual bDMARD discontinuation rate and the modification of PsARC and PASI90 response to ixekizumab or secukinumab.

Conclusion

Ixekizumab provided more QALYs at a lower cost than secukinumab, with differences being on a relatively small scale. Sensitivity analysis showed that base-case results were generally robust to changes in most input parameters.

Trial registration number

SPIRIT-P1: NCT01695239; Post-results, SPIRIT-P2: NCT02349295; Post-results.

Keywords: ixekizumab, secukinumab, cost-effectiveness analysis, Spanish population, psoriatic arthritis, biologics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A cost-effectiveness analysis was performed from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System comparing two interleukin-17A antagonists: ixekizumab and secukinumab.

The framework of this model is aligned with the York model; the ‘gold standard’ model for the economic evaluation of biological treatments in psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

The current model uses a combined response criterion of Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria and Psoriasis Area Severity Index to capture both joint and skin manifestations of PsA.

This analysis was limited by a lack of data available for costs and efficacy of supportive care given to patients with PsA in Spain.

Due to uncertainty regarding the annual all-cause discontinuation rate, this model used assumptions consistent with previous models.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease characterised by pain, swelling and erosion of the joints.1 PsA affects approximately 0.25% of the population worldwide1 and 0.6% of the adult population in Spain.2 PsA commonly coexists with psoriasis, developing in up to 30% of psoriatic patients, and over 90% of patients with PsA will have concomitant psoriasis.3 4 As a lifelong condition, PsA has a detrimental impact on quality of life due to pain and/or physical functional limitations associated with the disease.1 3 It is also associated with substantial use of healthcare resources and high socioeconomic costs.5 6

A number of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), which inhibit key inflammatory cytokines, are approved for treating patients with PsA. Interleukin (IL)-17 has been identified as an effective target for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including PsA.1 3 Ixekizumab, a high-affinity monoclonal antibody, is the most recently approved bDMARD targeting IL-17A for PsA, joining secukinumab, which uses the same target and similar mode of action.7 8 bDMARDs are considered major drivers of healthcare costs,5 and the cost effectiveness of these therapies often comes under scrutiny. Cost effectiveness analyses (CEAs) comparing bDMARDs have been conducted using the York model,9 an established economic framework, which, together with its subsequent versions, is considered the ‘gold standard’ for conducting CEAs in PsA.10 11

As inhibition of IL-17A is a relatively new mechanism of action, drugs in this class have not been the focus of CEAs.12 To date, there are no published CEAs comparing ixekizumab with secukinumab (another IL-17A inhibitor) in Spain.

We conducted a CEA assessing the cost effectiveness, in terms of the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, of ixekizumab versus secukinumab in bDMARD-naïve patients with active PsA and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (NHS). Secukinumab was selected as a comparator for this CEA as both drugs belong to the same class, and this may be of interest to decision makers assessing these IL-17A inhibitors. In addition, both drugs are approved for the treatment of PsA and plaque psoriasis and have demonstrated high efficacy, particularly on skin symptoms.7 8 This CEA focused on bDMARD-naïve patients, as this patient population may receive greater clinical benefit from earlier (ie, first-line) treatment.13

Methods

Model overview

A Markov model was developed to assess the cost effectiveness of ixekizumab versus secukinumab in a hypothetical cohort of bDMARD-naïve patients with active PsA and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Spain. The Markov model framework accommodates different health states and is based on the assumption that future events depend on the current health state of the patient. The model was programmed in Visual Basics for Applications with a user interface in Microsoft Excel.

The model is based on the most recent version of the York model11 with monthly cycles and a lifetime horizon, which was considered appropriate to reflect the chronic nature of PsA, as well as the treatment aim of delaying disease progression.14 The model incorporated age-dependent and gender-dependent mortality data for the normal Spanish population. Mean age and gender distribution was taken from the patient population in the SPIRIT-P1 and SPIRIT-P2 trials of ixekizumab in PsA.15 16 Increased PsA-specific mortality risks from two different sources17 18 were implemented in scenario analyses.

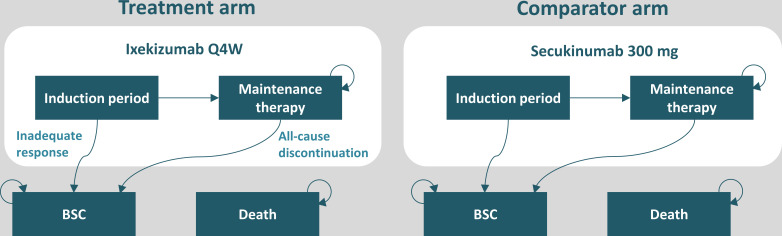

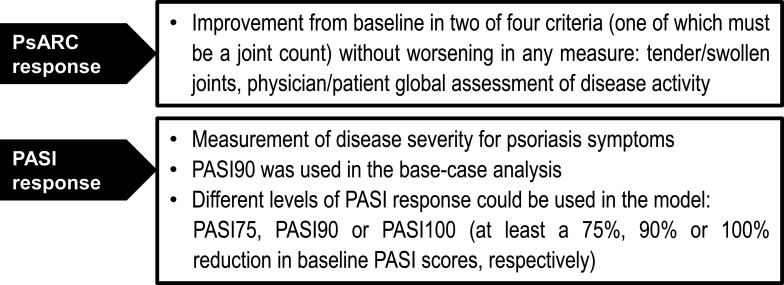

The model includes four health states: (1) a bDMARD induction period of 12 or 16 weeks, (2) maintenance bDMARD therapy, (3) best supportive care (BSC) and (4) death (figure 1). A combination of Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC) and Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) was used to measure joint and skin response at the end of the induction period and to determine treatment continuation of ixekizumab and secukinumab (figure 2).19 20 The induction period was set to 12 weeks and 16 weeks for ixekizumab and secukinumab, respectively. The induction period was chosen to reflect the time at which treatment efficacy is usually followed up in clinical practice (approximately 3 months in Spain).21 22 The difference in the length of induction period between the two drugs also acknowledges a degree of difference in the availability of clinical trial data for ixekizumab and secukinumab (ie, across the included studies, more week 16 than week 12 data are available for secukinumab). The PsARC response to treatment was defined as an improvement from baseline in two of four criteria without worsening in any measure: tender/swollen joints and physician/patient global assessment of disease activity (one of which must be a joint count). In a consensus from the Spanish Psoriasis Group, a panel of dermatologists agreed that a complete or nearly complete PASI response is the most relevant measure of effectiveness in clinical practice.23 With this in mind, ≥90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score (PASI90) was chosen in the base-case analysis as part of the response criteria and the treatment effect measures in this model.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the model structure in biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Dosage regimens were aligned with the European market authorisation. Although not shown in the figure, patients could transition to death from any state. BSC, best supportive care; Q4W, every 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Combination of PsARC response and PASI90 was used to capture both joint and skin responses at the end of the induction period. PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PASI90, ≥90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score; PsARC, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria.

Treatment sequences

At the end of the induction period, responders transitioned to maintenance therapy, while non-responders and discontinuers transitioned to BSC (figure 1), in which patients were assumed to receive standard treatment, depending on their Health Assessment Questionnaire‒Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and PASI status.24 Dosage regimens for ixekizumab and secukinumab were aligned with the European market authorisation.7 8 During maintenance therapy, patients were assumed to face a constant risk of all-cause treatment discontinuation, which was reflected by an annual discontinuation rate of 16.5% in line with previously applied methods.10 11

In the base-case analysis, baseline cohort characteristics were reflective of the demographic data from the ixekizumab SPIRIT-P1 and SPIRIT-P2 clinical trials15 16 (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the target population of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis based on the ixekizumab SPIRIT-P1 and -P2 clinical trials

| Parameter | Mean value |

| Age (years) | 51.0 |

| Proportion male (%) | 51.8 |

| Proportion female (%) | 48.2 |

| Body weight (kg) | 87.0 |

| Baseline HAQ-DI score | 1.19 |

| Baseline PASI score | 20.4 |

Patient characteristics based on pooled data from the intent-to-treat trial populations of SPIRIT-P1 and SPIRIT-P2 with ixekizumab.15 16

HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire‒Disability Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index.

Treatment effect

While PsARC and PASI90 were used as the combined response criterion (ie, treatment continuation rule), the treatment effect was modelled as a change in baseline of the HAQ-DI and PASI scores,25 reflecting the joint and skin components of PsA, respectively. Baseline HAQ-DI and PASI scores were derived from the SPIRIT-P1 and SPIRIT-P2 trials15 16 (table 1). Treatment effect, represented by improvement (ie, reductions) in HAQ-DI and PASI scores, was assumed to be instantaneous; as such, the response was also applied during the induction period. Absolute change in HAQ-DI and PASI scores is based on data from a network meta-analysis (NMA).25 26 Key efficacy input data, derived from the NMA,25 26 are provided in online supplementary table 1.

bmjopen-2019-032552supp001.pdf (29.2KB, pdf)

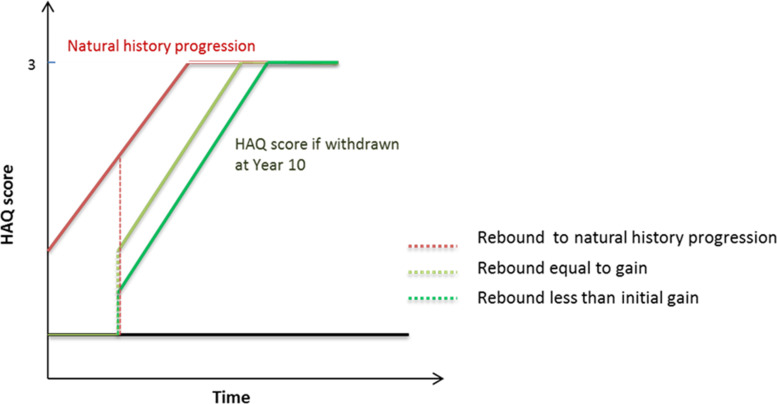

For patients who met the combined response of PsARC and PASI90 at the end of the induction period, the initial improvements in HAQ-DI and PASI continued during maintenance therapy until they transitioned into BSC. For patients entering BSC following discontinuation, it was assumed that some benefit was maintained from the initial bDMARD treatment. In the base case, for patients progressing to BSC, the HAQ-DI score was assumed to revert to the baseline HAQ-DI level prior to discontinuation (‘rebound equal to initial gain’). The rebound effect was assumed to be immediate and patients were modelled to progress at the same rate as natural history progression (an increase of 0.018 per 3-month period) (figure 3). For the PASI score, it was assumed that for non-responders not meeting PASI90, there would still be some gain in PASI—although lower—while they were treated with a bDMARD in the induction period. Once in the BSC state, due to the progressive nature of PsA, it was assumed that patients would deteriorate at a rate of natural progression.

Figure 3.

Scenarios for Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index rebound after the discontinuation of treatment. HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire.

Health utilities

Health utilities were based on HAQ-DI and PASI scores from the SPIRIT-P1 and SPIRIT-P2 clinical trials15 16 with Spanish tariffs applied. Calculation of utilities followed the established methodology of mapping the three-level version of EuroQol-5 Dimensions utilities on HAQ and PASI scores using a parsimonious linear regression model without further covariates or interaction terms.9–11 Alternative coefficients based on a similar algorithm using different data were applied in a sensitivity analysis. Utilities were calculated in each model cycle by multiplying Health Assessment Questionnaire and PASI levels with the estimated regression coefficients.

Resource use and costs

As the CEA was conducted from the perspective of the Spanish NHS, only direct medical costs were considered in the model, and included medication, injection training, physician visits and therapy monitoring. Drug acquisition costs were derived from the Botplus database in Spain,27 and costs for the administration and monitoring of treatments were obtained from various sources in Spain28 (table 2). Drug costs were based on the list prices as of Q4 2018. Monitoring costs were based on the costing schedule published in 2017, which was still valid in 2018. Due to a lack of healthcare resource utilisation data by drug or class, healthcare costs and resource use related to the administration and monitoring of bDMARDs were determined by an expert panel of four Spanish physicians (two rheumatologists and two dermatologists).

Table 2.

Costs for administration and monitoring of treatment in Spain

| Resource | Cost | Source |

| Drug acquisition costs (list prices) | ||

| Ixekizumab 80 mg Q4W prefilled pen | €934.25 per dose | Botplus database27 minus rebate of 7.5% according to Spanish regulation RDL 8/2010 |

| Secukinumab 300 mg prefilled pen | €1057.38 per dose | Botplus database27 minus rebate of 7.5% according to Spanish regulation RDL 8/2010 |

| Visits | ||

| Rheumatologist | €220.62 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| Dermatologist | €100.58 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| GP | €33.86 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| Monitoring | ||

| Full blood count | €67.98 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | €1.03 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| Chest X-ray | €42.23 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| Tuberculosis test | €8.95 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

| C reactive protein test | €8.95 | Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles28 |

GP, general practitioner; Q4W, every 4 weeks; RDL, Royal Decree-Law.

The severity of arthritis and psoriasis also may have an impact on healthcare costs.10 11 To reflect this, costs related to HAQ-DI and PASI were also included per cycle in the model.10 24 These costs were derived by converting and inflating results of established algorithms, which relate cost to absolute HAQ-DI and PASI values.

Aside from costs related to HAQ-DI and PASI, no additional costs were applied for patients in BSC. The costs of serious adverse events (ie, requiring hospitalisation) associated with bDMARD treatment were not included in the base-case analysis, but they were included in a sensitivity analysis. The rates of adverse events were derived from the summary of product characteristics of ixekizumab and secukinumab.7 8 Both costs and health utilities were discounted by 3% in the base case.

Sensitivity analyses

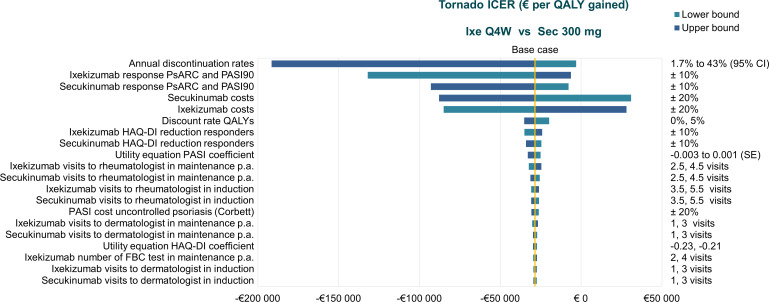

To explore the uncertainty inherent in the model, one-way (deterministic) sensitivity analysis, probabilistic sensitivity analysis and scenario analyses were undertaken. In the one-way sensitivity analysis, one variable at a time was altered to examine the effect on the results. Most input parameters varied by ±20% of the mean value, as 95% CI values were not available. Exceptions to this included ranges of values used for the annual discontinuation rate (95% CI), discount rates for costs and health utilities (0% and 5%), treatment efficacy (±10% of the mean value), HAQ-DI improvement conditional on response (NMA results), physician and monitoring costs (±1 visit), and utility equations for PASI and HAQ-DI coefficients.

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted by assigning distributions to input parameters (online supplementary table 2) and sampling from these distributions in 1000 iterations. For efficacy inputs, the convergence diagnostics and output analysis of the Bayesian NMA was used instead of applying parametric distributions, in line with internationally recognised technical guidance.29 The input parameters included PsARC and PASI response rates, changes in HAQ-DI based on response criterion, costs based on HAQ-DI and PASI, discontinuation rates, various healthcare-related costs and the use of resources.

bmjopen-2019-032552supp002.pdf (61.2KB, pdf)

A scenario analysis was conducted using a 10-year time horizon and alternative inputs for discount rates, increased PsA mortality, the definition of responders, the HAQ-DI rebound method, the utility equation, health state costs and placebo efficacy in BSC.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, planning or execution of this work.

Results

Results of the base-case analysis in bDMARD-naïve patients with PsA and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis are summarised in table 3. Ixekizumab was associated with total cost savings of €2658 compared with secukinumab (total costs €153 901 vs €156 559). Total QALYs were higher for ixekizumab (9.175 vs 9.082, difference 0.093). Although ixekizumab performed favourably over secukinumab in the base-case analysis, cost savings and QALY gains were modest.

Table 3.

Results of the base-case analysis comparing ixekizumab and secukinumab in biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

| Parameter | Ixekizumab | Secukinumab | Difference |

| Costs (year 2018 values) | |||

| Total costs | €153 901 | €156 559 | −€2658 |

| Treatment costs | €26 424 | €27 729 | −€1305 |

| Administration costs | €26 | €24 | €2 |

| Physician visit costs | €4141 | €4202 | −€61 |

| Monitoring costs | €797 | €706 | €92 |

| On treatment HAQ-DI/PASI-related costs | €4608 | €4115 | €494 |

| BSC costs | €117 904 | €119 784 | −€1880 |

| QALYs | |||

| Total QALYs | 9.175 | 9.082 | 0.093 |

BSC, best supportive care; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire‒Disability Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years.

The deterministic sensitivity analysis showed that base-case results were generally robust to changes in most input parameters but were most sensitive to the annual discontinuation rate for bDMARD therapy and modifications in PsARC and PASI90 response to ixekizumab or secukinumab (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of the one-way sensitivity analysis in biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis. FBC, full blood count; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index; ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio; Ixe, ixekizumab; p.a., per annum; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PASI90, ≥90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score; PsARC, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; Q4W, every 4 weeks.

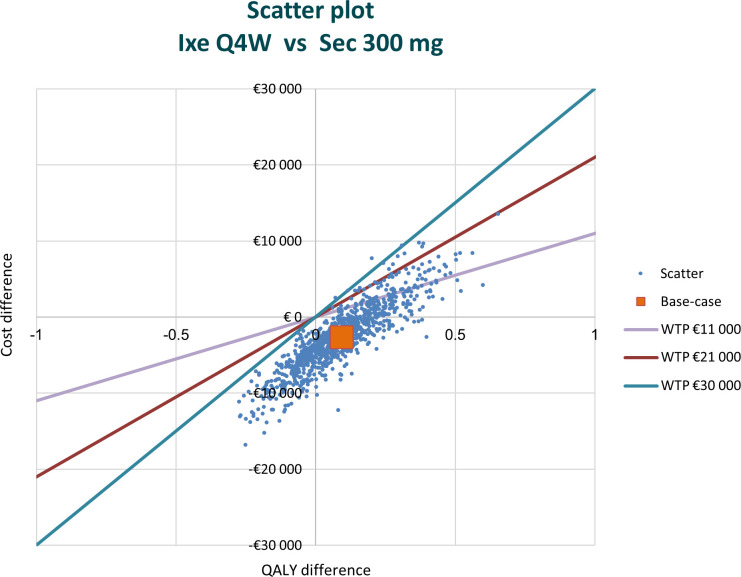

The probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that approximately 49.5% of observations were in the southeast quadrant, indicating that ixekizumab was still less costly and provided more QALYs than secukinumab (figure 5). Across the cost effectiveness plane, 99% of replications were located southeast of the line defined by a willingness to pay a threshold of €30 000 per QALY gained.

Figure 5.

Results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis in biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Approximately 49.5% of observations were in the southeast quadrant; 28.6% were in the southwest quadrant; and 21.9% were in the northeast quadrant of the cost effectiveness plane. Ixe, ixekizumab; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Sec, secukinumab; WTP, willingness to pay.

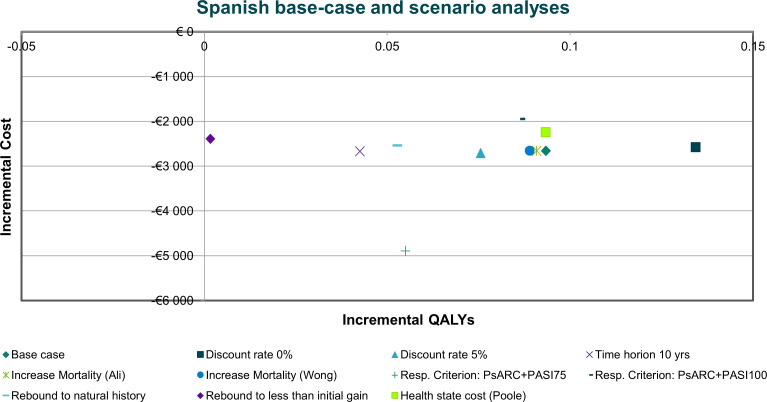

Overall, the scenario analyses showed that most of the parameters tested had relatively little impact on the base-case results (figure 6). In most scenarios, ixekizumab provided more QALYs at a lower cost than secukinumab. While there was some variability regarding incremental cost and QALYs between ixekizumab and secukinumab, in all scenarios, the mean results still indicated the dominance of ixekizumab over secukinumab.

Figure 6.

Results of scenario analyses in biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis. PASI100, 100% reduction in Psoriasis Area Severity Index score; PASI75, ≥75% reduction in Psoriasis Area Severity Index score; PsARC, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; Resp., response.

Discussion

In this CEA, the cost effectiveness of ixekizumab compared with secukinumab was evaluated in bDMARD-naïve patients with active PsA and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis from the perspective of the Spanish NHS. In general, ixekizumab performed favourably compared with secukinumab in the base-case analysis, with differences in cost savings and QALY gains being modest. The total difference in cost between ixekizumab and secukinumab was −€2658, with a small total difference in QALYs of 0.093. In the deterministic sensitivity analysis, the most influential variables were the annual discontinuation rate and the PsARC and PASI90 response for ixekizumab and secukinumab.

The framework of this model is closely aligned with the most recently revised version of the York model,11 which is considered a ‘benchmark’ model for the economic evaluation of biological treatments in PsA. The original York model has subsequently been revised to accommodate the analysis of patient subgroups. The model used in this analysis includes this amendment as a key feature. The current model also allows for combining PsARC and PASI as a response criterion, therefore capturing both joint and skin responses. A combined response criterion presents a more realistic representation of this multifaceted disease and may be especially useful when evaluating clinical benefits of bDMARDs, such as IL-17A antagonists, which are known for their proven efficacy on skin response.30 31

A limitation of this analysis was a lack of current data for health state cost estimates and the efficacy of BSC. There is also uncertainty regarding the annual all-cause discontinuation rate; therefore, our model used input data consistent with previously applied methods.10 11 Given the sensitivity of the results to this parameter, correction or confirmation of the current assumptions based on mature real-world drug survival data is a clear research need for the future.

In addition, the actual acquisition costs of bDMARDs in clinical practice tend to differ from list prices because any confidential discounts are unknown and therefore cannot be reflected in the analyses. Therefore, the respective differences in drug prices in clinical practice would also affect the true cost differences between treatment arms in the analysis.

It should also be noted that the NMA,25 26 which provided key efficacy data for this analysis, may not include some very recently published studies. However, at the time the NMA was performed, all relevant evidence available for approved drugs was included and any studies published after are unlikely to have a substantial impact on the NMA findings, and by extension the results of this analysis.

Conclusion

In this CEA of ixekizumab versus secukinumab in bDMARD-naïve patients with PsA and concomitant moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Spain, ixekizumab provided more QALYs at a lower cost, with differences being on a relatively small scale. As differences in total costs and QALYs were modest, other factors, such as patient preferences, may also be considered during clinical decision making. Base-case results were generally robust to modifications in most input parameters but were most sensitive to the annual bDMARD discontinuation rate and variations in PsARC and PASI90 response to ixekizumab or secukinumab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Elinor Wylde and Greg Plosker (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of the manuscript, funded by Eli Lilly.

Footnotes

Contributors: BS and CM were involved with the conception and design of the work, and the interpretation of the data. MN and CS were involved with the acquisition and interpretation of the data. TD was involved with the conception of the work and interpretation of the data. SH was involved with the interpretation of the data. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave their approval for the version to be published, had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Competing interests: BS and CM are full-time employees of ICON who were commissioned by Eli Lilly and Company to conduct the analysis for this work. MN, TD, CS and SH are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company; they receive a salary and own company stock.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.McArdle A, Pennington S, FitzGerald O. Clinical features of psoriatic arthritis: a comprehensive review of unmet clinical needs. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;55:271–94. 10.1007/s12016-017-8630-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seoane-Mato D, Sánchez-Piedra C, Díaz-González F, et al. THU0684 Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in adult population in Spain. Episer 2016 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:535–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:957–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1505557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciocon DH, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: separate or one and the same? Br J Dermatol 2007;157:850–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Angiolella LS, Cortesi PA, Lafranconi A, et al. Cost and cost effectiveness of treatments for psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:567–89. 10.1007/s40273-018-0618-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawalec P, Malinowski KP. The indirect costs of psoriatic arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2015;15:125–32. 10.1586/14737167.2015.965154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Medicines Agency Ixekizumab (Taltz): summary of product characteristics, 2016. Available: www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/taltz-epar-product-information_en.pdf [Accessed 22 Mar 2019].

- 8.European Medicines Agency Secukinumab (Cosentyx): summary of product characteristics, 2015. Available: www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/cosentyx-epar-product-information_en.pdf [Accessed 22 Mar 2019].

- 9.Woolacott N, Bravo Vergel Y, Hawkins N, et al. Etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1–239. 10.3310/hta10310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodgers M, Epstein D, Bojke L, et al. Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–329. 10.3310/hta15100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbett M, Chehadah F, Biswas M, et al. Certolizumab pegol and secukinumab for treating active psoriatic arthritis following inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2017;21:1–326. 10.3310/hta21560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasilewska A, Winiarska M, Olszewska M, et al. Interleukin-17 inhibitors. A new era in treatment of psoriasis and other skin diseases. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2016;33:247–52. 10.5114/ada.2016.61599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raychaudhuri SP, Wilken R, Sukhov AC, et al. Management of psoriatic arthritis: early diagnosis, monitoring of disease severity and cutting edge therapies. J Autoimmun 2017;76:21–37. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs 2014;74:423–41. 10.1007/s40265-014-0191-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:2317–27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31429-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali Y, Tom BDM, Schentag CT, et al. Improved survival in psoriatic arthritis with calendar time. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2708–14. 10.1002/art.22800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong K, Gladman DD, Husted J, et al. Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient clinic. I. causes and risk of death. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1868–72. 10.1002/art.1780401021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mease PJ, Antoni CE, Gladman DD, et al. Psoriatic arthritis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii49–54. 10.1136/ard.2004.034165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fransen J, Antoni C, Mease PJ, et al. Performance of response criteria for assessing peripheral arthritis in patients with psoriatic arthritis: analysis of data from randomised controlled trials of two tumour necrosis factor inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1373–8. 10.1136/ard.2006.051706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torre Alonso JC, Díaz Del Campo Fontecha P, Almodóvar R, et al. Recommendations of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on treatment and use of systemic biological and non-biological therapies in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatol Clin 2018;14:254–68. 10.1016/j.reuma.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Villaverde R, Rodriguez-Fernandez-Freire L, Galán-Gutierrez M, et al. Eficacia del secukinumab en psoriasis Y artritis psoriásica: Estudio multicéntrico retrospectivo. Med Clin (Barc) 2019;pii:S0025-7753(19):30006–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carretero G, Puig L, Carrascosa JM, et al. Redefining the therapeutic objective in psoriatic patients candidates for biological therapy. J Dermatolog Treat 2018;29:334–46. 10.1080/09546634.2017.1395794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobelt G, Jönsson L, Lindgren P, et al. Modeling the progression of rheumatoid arthritis: a two-country model to estimate costs and consequences of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2310–9. 10.1002/art.10471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Perry R, Watkins C, et al. Efficacy and safety of biologics in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. RMD Open 2020;6:e001117. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Sapin C, Hartz S, et al. THU0290 Effects of biologic dmards on physical function in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of network meta-analyses. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:363–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos Botplus database, 2018. Available: https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.aspx [Accessed 22 Mar 2019].

- 28.Oblikue Consulting Base de datos de costes sanitarios españoles: eSalud, 2007. Available: http://www.oblikue.com/bddcostes/ [Accessed 22 Mar 2019].

- 29.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for decision making 6: embedding evidence synthesis in probabilistic cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making 2013;33:671–8. 10.1177/0272989X13487257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betteridge N, Boehncke W-H, Bundy C, et al. Promoting patient-centred care in psoriatic arthritis: a multidisciplinary European perspective on improving the patient experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:576–85. 10.1111/jdv.13306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottlieb AB, Strand V, Kishimoto M, et al. Ixekizumab improves patient-reported outcomes up to 52 weeks in bDMARD-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis (SPIRIT-P1). Rheumatology 2018;57:1777–88. 10.1093/rheumatology/key161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032552supp001.pdf (29.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-032552supp002.pdf (61.2KB, pdf)