Abstract

Importance: Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is a common treatment for children with unilateral cerebral palsy (CP). Although clinic-based assessments have demonstrated improvements in arm function after CIMT, whether these changes are translated and sustained outside of a clinic setting remains unclear.

Objective: Accelerometers were used to quantify arm movement for children with CP 1 wk before, during, and 4 wk or more after CIMT; measurements were compared with those from typically developing (TD) peers.

Design: Observational.

Setting: Tertiary hospital and community.

Participants: Seven children with CP (5 boys, 2 girls; average [AVE] age ± standard deviation [SD] = 7.4 ± 1.2 yr) and 7 TD peers (2 boys, 5 girls; AVE age ± SD = 7.0 ± 2.3 yr).

Intervention: 30-hr CIMT protocol.

Outcomes and Measures: Use ratio, magnitude ratio, and bilateral magnitude were calculated from the accelerometer data. Clinical measures were administered before and after CIMT, and parent surveys assessed parent and child perceptions of wearing accelerometers.

Results: During CIMT, the frequency and magnitude of paretic arm use among children with CP increased in the clinic and in daily life. After CIMT, although clinical scores showed sustained improvement, the children’s accelerometry data reverted to baseline values. Children and parents in both cohorts had positive perceptions of accelerometer use.

Conclusions and Relevance: The lack of sustained improvement in accelerometry metrics after CIMT suggests that therapy gains did not translate to increased movement outside the clinic. Additional therapy may be needed to help transfer gains outside the clinic.

What This Article Adds: Accelerometer measurements were effective at monitoring arm movement outside of the clinic during CIMT and suggested that additional interventions may be needed after CIMT to sustain benefits.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a nonprogressive neurological disorder of movement and posture that affects approximately 2 of every 1,000 children in the United States (Cans et al., 2008). Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is one of the most recommended evidence-based treatments of children diagnosed with hemiparesis or unilateral CP (Novak et al., 2013; Sakzewski et al., 2013). CIMT has been used as a therapy technique with this population for almost 2 decades; it involves placing the nonparetic arm in a cast for a prescribed period of time with guided therapy to encourage use of the paretic arm (Taub et al., 2004). This therapy aims to create unimanual gains, with the goal of transfer to bimanual tasks outside the clinic.

Although the frequency and duration of treatment interventions can vary, CIMT has consistently resulted in clinical improvements for children with CP, including increased scores on the Assisting Hand Assessment (AHA; Krumlinde-Sundholm et al., 2007), the Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test (DeMatteo et al., 1993), and parent-reported paretic arm function (Hoare et al., 2007). Research has suggested that casting plays an important role in positive outcomes after CIMT by forcing the child to use the paretic arm, causing an increase in treatment intensity (Cope et al., 2008).

Although these described gains are important, prior research has also demonstrated a consensus on the use of quantitative measures to monitor movement outside the clinic (Uswatte et al., 2000). Advances in wearable technology have introduced new methods to more easily and accurately track human movement within and outside the clinic; specifically, since the 1980s, improvements in battery life, memory capabilities, cost, and size have made accelerometers an attractive solution for many research applications. Hildebrand and colleagues (2014) reported that accelerometers are the most commonly used objective measure of physical activity, and Borghese and colleagues (2017) called accelerometers the gold standard for monitoring physical activity in children.

Accelerometers have been used extensively to monitor steps and physical activity for children with CP and their typically developing (TD) peers. Although accelerometers have been used to monitor arm movement among adult stroke survivors, few studies have used similar methods for children with CP (Bailey et al., 2015); even fewer studies have investigated how therapy gains in children with CP have transferred learned skills to daily life. Gordon and colleagues (2007) used accelerometry metrics during a standardized clinical test (the AHA) before and after an intensive bimanual training to evaluate frequency of movement during the assessment. Similarly, Beani and colleagues (2019) used accelerometers to quantify how the hands were being used together during the AHA. Coker-Bolt and colleagues (2017) used accelerometers to monitor arm movements of children undergoing CIMT. They reported that 5 of 12 children receiving CIMT increased frequency of paretic arm movement compared with their nonparetic arm (measured by a use ratio) outside of the clinic after CIMT, although sensors were worn for only 6 hr on 1 day, roughly 1–2 wk before and after therapy. Because of variability in day-to-day activities, it has been reported that 3 days of data collection are necessary to achieve reliable estimates of movement patterns with accelerometers (Mitchell et al., 2015). In addition, it is unclear whether these increases would be sustained for longer durations of time after CIMT. To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared the amount of arm movement for children with CP before, during, and after CIMT with that of a group of TD peers, or reported the perspectives of parents and children on wearing accelerometers.

The purpose of this study was to use wearable accelerometers to monitor paretic and nonparetic arm movement of children with CP before, during, and after CIMT and compare their arm movement with that of TD peers. We hypothesized that during CIMT, children with CP would increase the frequency and magnitude of paretic arm use, which would be sustained after CIMT. We also examined perceptions of wearing accelerometers as a part of regular clinical care. Examinations of arm movement outside of the clinic can help health care professionals understand the transfer of therapeutic gains from therapy into daily life.

Method

Enrollment and Study Design

Seven children with CP and 7 TD children were included in this study (Table 1). The CP cohort was recruited through the CIMT program at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Of the 7 participants, 6 had prenatal or perinatal stroke or injury and 1 had had a postnatal stroke at age 5 yr that affected the child’s dominant side. Families enrolled in the CIMT program were given information about participation in this study and, if desired, were enrolled. TD children were recruited from the local community. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Participant | TD Cohort | CP Cohort | ||||||||

| Age, yr | Sex | Height, cm | Weight, kg | Age, yr | Sex | Height, cm | Weight, kg | MACS | Etiology | |

| 1 | 7 | Female | 128 | 26.1 | 7 | Male | 128 | 23.9 | 2 | Prenatal or perinatal stroke |

| 2 | 6 | Female | 124 | 28.3 | 7 | Female | 113 | 18.4 | 2 | Prenatal injury |

| 3 | 2 | Male | 93 | 13.8 | 6 | Male | 119 | 23.8 | 3 | Postnatal stroke |

| 4 | 9 | Female | 139 | 29.8 | 8 | Female | 130 | 32.6 | 3 | Perinatal stroke |

| 5 | 9 | Female | 141 | 26.4 | 7 | Male | 118 | 19.9 | 2 | Perinatal stroke |

| 6 | 7 | Male | 116 | 22.6 | 7 | Male | 139 | 50.0 | 1 | Prenatal or perinatal stroke |

| 7 | 9 | Female | 130 | 25.4 | 10 | Male | 136 | 32.0 | 2 | Perinatal intraventricular hemorrhage |

| AVE ± SD | 7.0 ± 2.3 | 124.4 ± 15.1 | 24.6 ± 4.9 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 126.1 ± 9.0 | 28.7 ± 10.1 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | |||

Note. AVE = average; CP = cerebral palsy; MACS = Manual Ability Classification System (Eliasson et al., 2006); SD = standard deviation; TD = typically developing.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy Protocol

All participants in the CP cohort received CIMT in accordance with the standard protocol at Seattle Children’s Hospital. A custom long-arm, univalve, fiberglass cast was fabricated, which extended from the child’s axillary region to beyond the distal end of the phalanxes. For 3 wk, unimanual training of the paretic arm occurred 2 hr/day, 4 days/wk (Monday–Thursday), and bimanual training took place 2 hr/day, once a week (Friday). The cast was worn in and out of therapy throughout the week, except for the 2-hr period on Friday when bimanual training occurred and the children’s skin was inspected. The training occurred in a small group setting: one therapist to two children, with assistance from an adult volunteer.

During therapy, shaping techniques were used. Shaping involves using motivating activities at the appropriate difficulty level to allow the child to have successful experiences while developing new skills (DeLuca et al., 2007). The goal of shaping is to untrain the developmental disregard associated with the paretic arm. Our shaping process consisted of the occupational therapist or occupational therapy assistant giving positive verbal or visual recognition to the children when they accomplished challenging tasks. As therapy continued, these positive cues were given only for more complex tasks, with the goal of encouraging the children to perform more challenging movements. Throughout the 3-wk protocol, extensive practice occurred to ensure skills acquisition.

Accelerometry Metrics

All children were fitted with triaxial ActiGraph GT9X Link accelerometers (ActiGraph Corp., Pensacola, FL), which were worn on both wrists. During CIMT, the CP cohort wore the ActiGraphs over the cast on the nonparetic arm. Parents and children were provided written and verbal instructions on basic wear and use. Data were collected at 100 Hz while the children were awake and not bathing or in water. Upon return of the ActiGraphs, data were downloaded through ActiLife (ActiGraph Corp., Pensacola, FL), and 1-s epoch (duration) activity counts were used for analysis, similar to prior research (Lang et al., 2017). Periods that reflected times of nonwear were excluded from data analysis. The CP cohort wore the accelerometers for 3 days during three time periods: (1) 1 wk before CIMT, (2) during the second week of CIMT, and (3) >4 wk after CIMT.

The periods before and after CIMT were designed to align with each child’s clinical appointments as part of undergoing CIMT and varied slightly for each child because of scheduling and family commitments. On average, children were seen 7 ± 2 (average ± standard deviation) days before CIMT and 7.6 ± 3.9 wk after completion of CIMT. Five of the 7 CP participants were seen 4–6 wk after CIMT; however, because of scheduling conflicts, the other 2 children were seen 11–15 wk after completion of CIMT. The TD cohort also wore the accelerometers for three 3-day periods temporally spaced to align with the CIMT protocol, but no intervention occurred. For all outcome measures, averages across the three periods were used for the TD cohort.

To evaluate magnitude and amount of arm movement, three outcome metrics were used: use ratio, magnitude ratio, and bilateral magnitude (Bailey et al., 2015; Urbin et al., 2015). Use ratio provides a measurement that lets one compare the frequency of activity between the paretic and nonparetic arms:

|

A use ratio equal to 1 indicates that the paretic and nonparetic arms were used an equal amount of time throughout the day, and values >1 indicate greater use of the paretic arm. To calculate hours of arm movement, the number of epochs with activity counts >0 were summed and converted to hours for each arm. Use ratio is often used because it gives a single numerical output from a large amount of data, which can be used to compare the activity frequency of each arm (Urbin et al., 2015).

The magnitude ratio was calculated as a metric to compare the magnitude of acceleration of the arms at each time point:

|

The magnitude was calculated by taking the vector magnitude of the activity counts for each epoch. Similar to prior research, the natural log was used to avoid skewness in the ratio caused by an underestimation of the denominator (van der Pas et al., 2011). Values >7 or <−7 were set to 7 and −7, respectively. The average magnitude was calculated for each period. A magnitude ratio near 0 indicates similar use of each arm, a negative number indicates more use of the nonparetic arm, and a positive number indicates more use of the paretic arm.

The bilateral magnitude was used to compare the overall movement of both arms together as a measure of bilateral arm movement:

As with the magnitude ratio, the vector magnitude of the activity counts was calculated for each epoch. A greater bilateral magnitude indicates greater overall movement of both arms. The same equations were used for the TD cohorts; however, the accelerations from their dominant and nondominant arms were used as the nonparetic and paretic arms, respectively.

Clinical Measures

Before and after CIMT, the occupational therapist performed a comprehensive evaluation of the arm function of each child with CP. The grip, pinch, and lateral pinch of the child’s paretic and nonparetic arms were measured using pinch and grip dynamometers; the maximum score over three trials was recorded. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM; Law et al., 2019), a client-centered clinical practice outcome assessment, was used to measure participant-identified problems of daily function. Children identified goals of self-care, productivity, or leisure and scored themselves on their performance and satisfaction. Finally, the Box and Block Test (Mathiowetz et al., 1985) was used as a standardized measure of coordination.

Parent Survey

Parents of children in both cohorts were given surveys after the second (during CIMT for the CP cohort) and third (after CIMT for the CP cohort) wave of data collection so we could assess parent and child attitudes toward wearing wearable sensors as a part of clinical care. Parents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with seven statements aimed at understanding the benefits and challenges families experienced in using wrist-worn accelerometers. The questions assessed comfort, aesthetics, and parents’ interest in accessing their child’s personalized accelerometry data. The survey also included three open-ended questions for parents to provide specific feedback regarding how to improve the technology for their child.

Statistical Analysis

Because of the small sample size, we used nonparametric tests for all comparisons. Friedman’s tests were used to compare data between visits for each cohort, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to evaluate differences between cohorts or time points (α = .05). All data analysis and statistical tests were conducted using custom programs in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).

Results

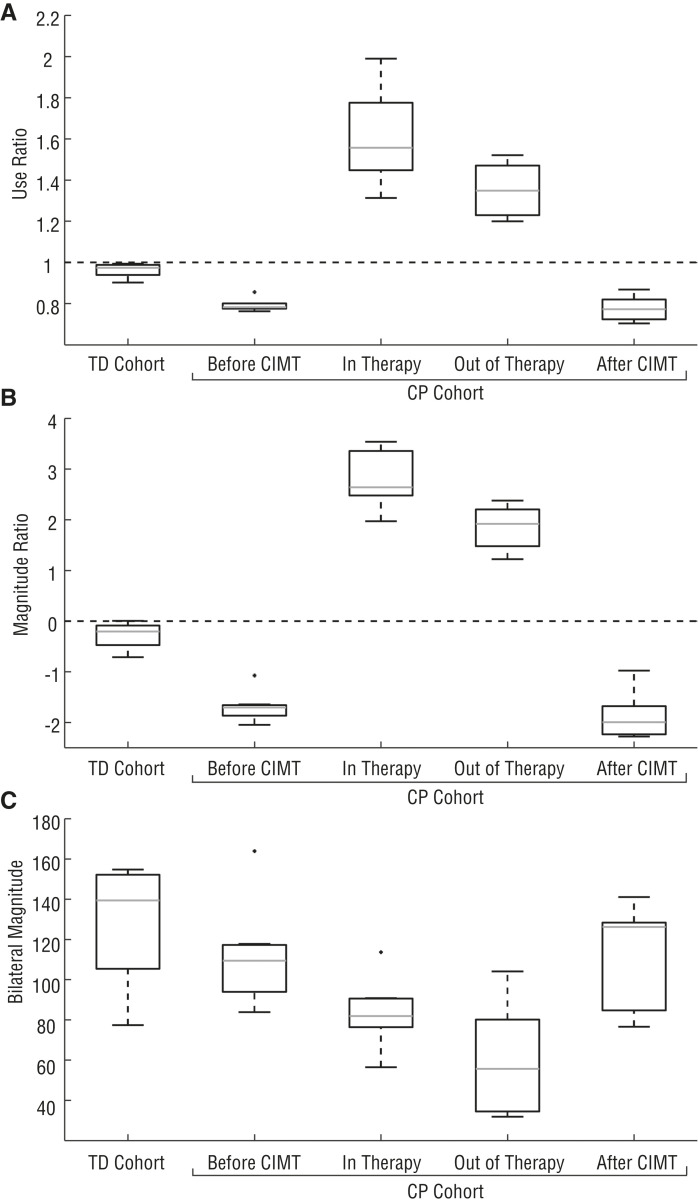

Before therapy, children with CP used their paretic arm significantly less than their nonparetic arm and less than their TD peers in daily life. The average use ratio of the CP cohort before therapy was 0.79 ± 0.03 versus 0.96 ± 0.03 for the TD cohort (p = .026; Figure 1). The magnitude ratio of the CP cohort during this pretherapy period was significantly less than that of the TD cohort at −1.70 ± 0.28 and −0.28 ± 0.24, respectively (p = .026). Even with the decrease in paretic arm movement, the combined arm movement of the CP cohort during this period stayed similar to that of the TD cohort; the bilateral magnitude was 111.6 ± 24.3 for the CP cohort and 126.7 ± 27.4 for the TD cohort (p = .46). No significant difference was found in arm movement for the TD cohort across the three time periods for the use ratio (p = .56), magnitude ratio (p = .28), or bilateral magnitude (p = .066).

Figure 1.

Use ratio (Panel A), magnitude ratio (Panel B), and bilateral magnitude (Panel C) for the typically developing (TD) and cerebral palsy (CP) cohorts.

Note. The averages over the three time periods are shown for the TD cohort. For the CP cohort, results are shown for each period: before constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), during CIMT (including time both in therapy at the hospital and out of therapy), and after CIMT. The dashed lines in Panels A and B show equal arm movement: a value of 1 for use ratio and 0 for magnitude ratio.

During CIMT, the children with CP significantly increased their use ratio and magnitude ratio in therapy (while working with a therapist) and out of therapy (at school, home, etc.) compared with pre-CIMT (Figure 1). The use ratio increased to 1.61 ± 0.21 (p = .00058) while in therapy and 1.36 ± 0.12 (p = .0023) while out of therapy but still wearing the cast. Similarly, the magnitude ratio increased to 2.80 ± 0.53 (p = .00058) in therapy and 1.85 ± 0.40 (p = .0023) out of therapy. We noted a significant difference in the use ratio and magnitude ratio when we compared time in therapy and time out of therapy (p = .026 and p = .0041, respectively). Children’s overall movement, measured by the bilateral magnitude, decreased both in therapy (84.19 ± 16.12, p = .018) and out of therapy (58.95 ± 25.67, p = .007), suggesting less overall movement of both arms while participating in CIMT.

After CIMT, the CP cohort returned to baseline values for all accelerometry outcomes. The use ratio (0.78 ± 0.06, p = .26), magnitude ratio (−1.87 ± 0.42, p = .26), and bilateral magnitude (110.0 ± 24.7, p = .90) were not significantly different from pre-CIMT values (Figure 1); however, the children with CP showed improvements in the clinical measures after CIMT compared with pre-CIMT (Table 2). There was a significant increase in grip strength and increases, although not significant, in three-point pinch, lateral pinch, and performance on the Box and Block Test for the paretic arm. In addition, the children with CP ranked themselves as more able to reach their self-identified goals after CIMT, as measured by the COPM. The children rated themselves higher on their performance and satisfaction with reaching their bimanual goals and unimanual goals after CIMT.

Table 2.

Changes in Clinical Measures After CIMT

| Measure | Paretic | Nonparetic | ||

| AVE ± SD | p | AVE ± SD | p | |

| Grip, lb | 8.3 ± 7.3 | .05 | −0.1 ± 1.3 | .89 |

| 3-point pinch, lb | 3.2 ± 5.0 | .40 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 1.00 |

| Lateral pinch, lb | 1.5 ± 1.0 | .12 | −1.3 ± 0.1 | .10 |

| Box and Block Test, no. blocks | 4.3 ± 5.1 | .38 | −0.3 ± 5.9 | .97 |

| Performance/Satisfaction | ||||

| COPM unimanual | 2.2 ± 1.1/2.5 ± 1.3 | .009/.007 | ||

| COPM bimanual | 4.6 ± 2.5/4.8 ± 2.6 | .0003/.0003 | ||

Note. AVE = average; CIMT = constraint-induced movement therapy; COPM = Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; SD = standard deviation.

Families in both the TD and CP cohorts had positive perceptions of wearing accelerometers but were generally neutral on whether accelerometers should be integrated into clinical care (Table 3). Families in both cohorts emphasized the comfort of the sensors and wanted to learn from the data gained from the sensors, specifically about how their child’s arm movement and function had changed after CIMT. In addition, parents suggested that their child would have been more compliant wearing the sensors if the sensors interacted with the child (e.g., by using lights). No significant differences were found between cohorts in questionnaire responses.

Table 3.

Parent Survey Responses

| Survey Item | AVE ± SD | |

| CP | TD | |

| Sensors were comfortable for my child to wear. | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.7 |

| My child did not want to wear the sensors. | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| My child enjoyed wearing the sensors. | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.8 |

| The sensors interfered with daily activities. | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.9 |

| The sensors were a conversation starter. | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| I wish we could learn more about the data from the sensors. | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 1.1 |

| Wearable sensors should be part of clinical care. | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 1.0 |

Note. The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). AVE = average; CP = cerebral palsy; SD = standard deviation; TD = typically developing.

Discussion

CIMT, which aims to produce unimanual gains that will transfer to bimanual arm use outside of the clinic and be sustained after the completion of the therapy, is a common treatment for children with unilateral CP. The purpose of this study was to quantify arm use before, during, and after CIMT and make comparisons with TD peers using accelerometry. Among a cohort of 7 children with unilateral CP, we found that the therapy combined with the cast increased the amount (use ratio) and intensity (magnitude ratio) of paretic arm use, not only while children were actively engaged in therapy at the hospital (2 hr/day) but also while they were in the community, confirming that the cast effectively increased use and practice of the paretic arm in both environments. However, the results demonstrated a decrease in overall activity level during CIMT (bilateral magnitude), especially outside of therapy, which may suggest that casting has a detrimental effect on activity and participation in home and community activities. Moreover, after CIMT we observed a return to baseline for all accelerometer measures, indicating that gains in paretic arm use were not maintained after therapy concluded. These results suggest that new strategies or home exercise programs, such as remind-to-move (RTM) or other follow-up programs, may be necessary to maintain increased paretic arm use and improved functional skills in daily life after CIMT (Dong & Fong, 2016).

Accelerometers have previously been used with children with CP to evaluate movement (Sokal et al., 2015), and our results parallel many previous findings. The difference in magnitude ratio between the cohorts in this study was similar to differences in asymmetry index (also measured with an accelerometer) between CP and TD cohorts measured during a clinical exam (Beani et al., 2019). Coker-Bolt and colleagues (2017) observed improvements in paretic arm function 1–2 wk after CIMT for 5 of their 12 participants. We did not observe similar improvements >4 wk after CIMT, suggesting that additional intervention may be needed to maintain improvements. The use ratios and magnitude ratios reported here also had a much smaller range than in Coker-Bolt et al.’s study. Some of the baseline use ratios and magnitude ratios Coker-Bolt et al. reported were closer to those of our TD cohort, suggesting they may have had a more heterogeneous group that included some children with CP with less impaired arm movement.

Similar to prior research, clinical measures improved after CIMT, including improvements in grip and pinch strength and child- or parent-reported goals (Gordon, 2011; Stearns et al., 2009). In examining the COPM results, we noted that 63% of the goals chosen by the children with CP were bimanual goals, similar to the 85% previously reported by Gordon and colleagues (2007). Although CIMT emphasizes unilateral practice of the paretic arm, these child-reported goals, along with our finding that bilateral magnitude decreased during CIMT, may support combinations of CIMT with bimanual therapy. An RTM protocol has been used in other studies to create more self-awareness of the paretic arm (Dong & Fong, 2016; Dong et al., 2017). The RTM protocol involves wearing a sensory cuing device on the paretic arm that vibrates every 15 min and reminds the child to use the paretic arm. To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared the effects of traditional CIMT to the effects of CIMT followed by RTM; however, the combination could facilitate the transfer of unimanual skills gained in CIMT to bimanual tasks in daily living.

The results of this study are limited because of the small number of children in each cohort. There were differences between our CP and TD cohorts in age and gender, but although we observed similar trends across children we could not evaluate the effect of age or sex because of the small sample size. Moreover, because CP encompasses a heterogeneous population, there may not be enough children in this cohort to represent trends for the entire population with CP. Conclusions regarding which children benefit most from CIMT require further research. Independent factors, including age, onset of hemiplegia, location of brain injury, and side of hemiplegia, may influence the benefits of CIMT, but these trends cannot be determined from the current data set. In addition, there are numerous variations of CIMT with different frequencies, intensities, and total durations (Sakzewski et al., 2015). The results presented here are applicable only for this specific protocol, with a total dosage time of 30 hr. The accelerometry results described in this article were recorded from wrist-worn accelerometers, thus giving only overall arm movement data. This analysis assumed that if children improved their finger movements, they would also have improved their arm movements; at this time, we do not have the technology to measure finger movements accurately outside of the clinic.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice and Research

The results of this study have the following implications for occupational therapy practice and research:

A 30-hr CIMT protocol resulted in increased grip strength of the paretic hand and improvement in children’s perception of their ability to accomplish their goals.

Wearing a cast in and out of therapy promoted more paretic arm movement compared with before CIMT; however, there was an overall decrease in movement of both arms while wearing this cast, which should be taken into consideration when developing home activities during CIMT.

After CIMT, children returned to baseline values for arm movement in daily life, suggesting that additional strategies may be needed to translate gains from CIMT into activities of daily living in their home, school, and community settings.

Families and children in both cohorts had positive perceptions of and experiences with using accelerometers as a method to monitor movement outside of the clinic.

Conclusion

Although the CP cohort improved accelerometry-measured metrics of arm movement during therapy, all metrics fell back to baseline values after therapy. However, the children did show continued improvements in standard measures of clinical function. The lack of sustained accelerometry improvements after CIMT suggests that unimanual skills gained in therapy are not maintained more than 4 wk after therapy. Parents’ and children’s positive perceptions of wearing accelerometers support their further use to monitor movement and inform care for children with CP.

Acknowledgments

Brianna M. Goodwin and Emily K. Sabelhaus contributed equally to this article. This project was supported by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Academic Enrichment Fund and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (Grant R01-EB021935). We thank the occupational therapists, occupational therapy assistants, and families for their time and engagement; without them this research would not have been possible.

Contributor Information

Brianna M. Goodwin, Brianna M. Goodwin, MS, is Research Engineer, Division of Health Care Policy and Research, Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. At the time of the research, she was Graduate Student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, and Clinical Research Assistant, Rehabilitation Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA.

Emily K. Sabelhaus, Emily K. Sabelhaus, MS, OTR/L, is Occupational Therapist, Rehabilitation Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, and Pediatric Occupational Therapist, Whatcom Center for Early Learning, Bellingham, WA.

Ying-Chun Pan, Ying-Chun Pan, BS, is Graduate Student, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. At the time of the research, he was Undergraduate Student, Department of Bioengineering, University of Washington, Seattle, and Clinical Research Assistant, Rehabilitation Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA..

Kristie F. Bjornson, Kristie F. Bjornson, PT, PhD, is Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle.

Kelly L. D. Pham, Kelly L. D. Pham, MD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, and Assistant Professor, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA.

William O. Walker, William O. Walker, Jr., MD, is Robert Aldrich Endowed Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

Katherine M. Steele, Katherine M. Steele, PhD, is Albert S. Kobayashi Endowed Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle; kmsteele@uw.edu

References

- Bailey R. R., Klaesner J. W., & Lang C. E. (2015). Quantifying real-world upper-limb activity in nondisabled adults and adults with chronic stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 29, 969–978. 10.1177/1545968315583720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beani E., Maselli M., Sicola E., Perazza S., Cecchi F., Dario P., . . . Sgandurra G. (2019). ActiGraph assessment for measuring upper limb activity in unilateral cerebral palsy. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation, 16, 30 10.1186/s12984-019-0499-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese M. M., Tremblay M. S., LeBlanc A. G., Leduc G., Boyer C., & Chaput J. P. (2017). Comparison of ActiGraph GT3X+ and Actical accelerometer data in 9–11-year-old Canadian children. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35, 517–524. 10.1080/02640414.2016.1175653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cans C., De-la-Cruz J., & Mermet M.-A. (2008). Epidemiology of cerebral palsy. Paediatrics and Child Health, 18, 393–398. 10.1016/j.paed.2008.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coker-Bolt P., Downey R. J., Connolly J., Hoover R., Shelton D., & Seo N. J. (2017). Exploring the feasibility and use of accelerometers before, during, and after a camp-based CIMT program for children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 10, 27–36. 10.3233/PRM-170408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope S. M., Forst H. C., Bibis D., & Liu X.-C. (2008). Modified constraint-induced movement therapy for a 12-month-old child with hemiplegia: A case report. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 430–437. 10.5014/ajot.62.4.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca S., Echols K., & Ramey S. L. (2007). ACQUIREc therapy: A training manual for effective application of pediatric constraint-induced movement therapy. Hillsborough, NC: MindNurture.

- DiMatteo C., Law M., Russell D., Pollock N., Rosenbaum P., & Walter S. (1993). The reliability and validity of the Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dong A.-Q. V., & Fong N.-K. K. (2016). Remind to move—A novel treatment on hemiplegic arm functions in children with unilateral cerebral palsy: A randomized cross-over study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 19, 275–283. 10.3109/17518423.2014.988304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong V. A., Fong K. N., Chen Y. F., Tseng S. S., & Wong L. M. (2017). “Remind-to-move” treatment versus constraint-induced movement therapy for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59, 160–167. 10.1111/dmcn.13216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson A.-C., Krumlinde-Sundholm L., Rösblad B., Beckung E., Arner M., Öhrvall A.-M., & Rosenbaum P. (2006). The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 48, 549–554. 10.1017/S0012162206001162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M. (2011). To constrain or not to constrain, and other stories of intensive upper extremity training for children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53(Suppl. 4), 56–61. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Schneider J. A., Chinnan A., & Charles J. R. (2007). Efficacy of a hand–arm bimanual intensive therapy (HABIT) in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A randomized control trial. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 49, 830–838. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M., van Hees V. T., Hansen B. H., & Ekelund U. (2014). Age group comparability of raw accelerometer output from wrist- and hip-worn monitors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46, 1816–1824. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare B., Imms C., Carey L., & Wasiak J. (2007). Constraint-induced movement therapy in the treatment of the upper limb in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A Cochrane systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21, 675–685. 10.1177/0269215507080783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumlinde-Sundholm L., Holmefur M., Kottorp A., & Eliasson A.-T. (2007). The Assisting Hand Assessment: Current evidence of validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 49, 249–264. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C. E., Waddell K. J., Klaesner J. W., & Bland M. D. (2017). A method for quantifying upper limb performance in daily life using accelerometers. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 122, e55673 10.3791/55673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Baptiste S., Carswell A., McColl M., Polatajko H., & Pollock N. (2019). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (5th ed., rev.). Altona, Manitoba, Canada: COPM Inc.

- Mathiowetz V., Volland G., Kashman N., & Weber K. (1985). Adult norms for the Box and Block Test of manual dexterity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39, 386–391. 10.5014/ajot.39.6.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L. E., Ziviani J., & Boyd R. N. (2015). Variability in measuring physical activity in children with cerebral palsy. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47, 194–200. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak I., McIntyre S., Morgan C., Campbell L., Dark L., Morton N., . . . Goldsmith S. (2013). A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 55, 885–910. 10.1111/dmcn.12246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakzewski L., Provan K., Ziviani J., & Boyd R. N. (2015). Comparison of dosage of intensive upper limb therapy for children with unilateral cerebral palsy: How big should the therapy pill be? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 37, 9–16. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakzewski L., Ziviani J., & Boyd R. N. (2013). Efficacy of upper limb therapies for unilateral cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 133, e175–e204 10.1542/peds.2013-0675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal B., Uswatte G., Vogtle L., Byrom E., & Barman J. (2015). Everyday movement and use of the arms: Relationship in children with hemiparesis differs from adults. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 8, 197–206. 10.3233/PRM-150334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns G. E., Burtner P., Keenan K. M., Qualls C., & Phillips J. (2009). Effects of constraint-induced movement therapy on hand skills and muscle recruitment of children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation, 24, 95–108. 10.3233/NRE-2009-0459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub E., Ramey S. L., DeLuca S., & Echols K. (2004). Efficacy of constraint-induced movement therapy for children with cerebral palsy with asymmetric motor impairment. Pediatrics, 113, 305–312. 10.1542/peds.113.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbin M. A., Waddell K. J., & Lang C. E. (2015). Acceleration metrics are responsive to change in upper extremity function of stroke survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96, 854–861. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uswatte G., Miltner W. H., Foo B., Varma M., Moran S., & Taub E. (2000). Objective measurement of functional upper-extremity movement using accelerometer recordings transformed with a threshold filter. Stroke, 31, 662–667. 10.1161/01.STR.31.3.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pas S. C., Verbunt J. A., Breukelaar D. E., van Woerden R., & Seelen H. A. (2011). Assessment of arm activity using triaxial accelerometry in patients with a stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92, 1437–1442. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]