Abstract

Background

GGPP (geranylgeranyl diphosphate) is produced in the isoprenoid pathway and mediates the function of various plant metabolites, which is synthesized by GGPPS (GGPP synthases) in plants. GGPPS characterization has not been performed in any plant species except Arabidopsis thaliana. Here, we performed a complete computational and bioinformatics analysis of GGPPS and detected their transcription expression pattern in Gossypium hirsutum for the first time so that to explore their evolutionary relationship and potential functions. Finally, we unravelled evolutionary relationship, conserved sequence logos, gene duplication and potential involvement in plant development and abiotic stresses tolerance of GGPPS genes in G. hirsutum and other plant species.

Results

A total of 159 GGPPS genes from 18 plant species were identified and evolutionary analysis divided these GGPPS genes into five groups to indicate their divergence from a common ancestor. Further, GGPPS family genes were conserved during evolution and underwent segmental duplication. The identified 25 GhGGPPS genes showed diverse expression pattern particularly in ovule and fiber development indicating their vital and divers roles in the fiber development. Additionally, GhGGPPS genes exhibited wide range of responses when subjected to abiotic (heat, cold, NaCl and PEG) stresses and hormonal (BL, GA, IAA, SA and MeJA) treatments, indicating their potential roles in various biotic and abiotic stresses tolerance.

Conclusions

The GGPPS genes are evolutionary conserved and might be involve in different developmental stages and stress response. Some potential key genes (e.g. GhGGPP4, GhGGPP9, and GhGGPP15) were suggested for further study and provided valuable source for cotton breeding to improve fiber quality and resistant to various stresses.

Keywords: GGPP, Gossypium hirsutum, Gibberelline, cis-elements, Sequence logos, Collinearity

Background

Isoprenoids represent the largest group of biologically active and specialized metabolites in plants. Many Isoprenoids provides protection to plants from pathogens and herbivores threats [1]. Isoprenoids also have important functions in plant photosynthesis and respiration processes and involve many hormonal pathways (abscisic acid, brassinosteroids, cytokinin, gibberellin, and strigolactones) important for development and growth regulation in plants [1–4].

In isoprenoid pathway, prenyl diphosphate synthases are active with important isozymes for isoprenoid metabolism, use isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) as substrates in the mevalonate (MVA) or methylerythritol (MEP) pathway. In general, they are represented by three enzymes such as geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), farnesyldiphosphate synthase (FPPS) and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS) in plants [4].

GGPPS is an essential enzyme among three isoprenoids for primary and secondary isoprenoid compounds synthesis such as chlorophylls, carotenoids and derivatives including different hormones (e.g. abscisic acid (ABA), strigolactones and gibberellins), and proteins (e.g. plastoquinones, ubiquinones, phylloquinones, tocopherols, diterpenoids, polyprenols, dolichols, and prenylated) [4]. GGPPS exerts successive additions of IPP to DMAPP, GPP and FPP as a homodimer [5] and have been studied in many organisms such as bacteria [6], yeast [7], fungi [8], plants [9], mammals [10] and insects [11].

In A. thaliana, 12 GGPPS genes were identified [12] and have been reported with their basic characterization date back more than a decade ago [4, 9, 13–15]. It is reported previously that 10 GGPPS paralogs (GGPPS1- GGPPS4 and GGPPS6-GGPPS11) out of 12 showed GGPPS activity and are functional in A. thaliana, however, GGPPS12 gene was studied in two works which demonstrated that GGPPS12 lack GGPPS activity [9, 15].

Furthermore, the GGPPSs were found in different cell organelles in A. thaliana Such as GGPPS1 existed in mitochondria, GGPPS4 in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum), and GGPPS2 and GGPPS6-GGPPS11 in plastids [9, 13–15]. In addition, GGPPS genes showed differential spatio-temporal expression both by Northern analysis and GUS expression of GGPPS promoters such as photosynthetically active tissues were found to be rich with GGPPS11 [4, 9] and provided GGPP as a substrate for biosynthesis of essential photosynthesis related isoprenoid compound. Similarly, GGPPS1- GGPPS10 were specifically expressed in root or seed tissues and are important during plant development [4]. Additionally, on the base of sequence analysis, GGPPS5 was proposed to be a pseudo gene [4], whereas GGPPS12 was almost different paralog from all predicted 12 GGPPSs in A. thaliana, and does not exhibit GGPP synthase activity [4, 9, 15]. However, GGPPS12 together with GGPPS11 was active as a heterodimer and can synthesize GPP [15].

Dicotyledonous plants diverged from their ancestors about 10–15 million years ago (MYA). The genus Gossypium contained 50 species and one of them is Gossypium hirsutum. G. hirsutum is an allotetraploid plant known as upland cotton. Researchers demonstrated that G. hirsutum emerged about 1–2 MYA as a result of an intergenomic hybridization event between G. arboreum and G. raimondii (A and D genomes) [16–18]. Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is the greatest source of natural fiber and is cultivated worldwide [19] as an important raw material for textile industry. There are many environmental and hormonal stresses that affect cotton growth and productivity which result in low fiber quality and yield. Advancements in cotton genome sequencing [20, 21] make it possible to conduct a complete and comprehensive investigation of cotton genes involve in plant growth and development.

Due to the important role of GGPPS for isoprenoid biosynthesis, we investigated the evolutionary relationships of the GGPPS genes in 17 plant species, representing major plant lineages (green algae, mosses, gymnosperms, and angiosperms) using a combination of computational analyses. Particularly, we performed a comprehensive analysis of entire G. hirsutum GGPPS family members and identified 25 GGPPS genes. In our study, we performed a systematic analysis of GhGGPPS genes using phylogenetic analysis. The biophysical properties, sequence logos, exon/intron and protein motif distribution, promoter cis-element analysis, chromosomal distribution, gene duplication, and colinearity analysis were performed. Moreover, tissue-specific expression patterns as well as abiotic and hormonal stress responses were also investigated for G. hirsutum GGPPS genes. The present study provides a foundation and deepens our understanding about molecular and biological functions of GGPPS genes in cotton.

Results

Identification of GGPPS genes in plants

A total of 159 GGPPS genes were identified from 18 plant species including green algae, mosses, fern, gymnosperms and angiosperms (Additional file 1:Table S1). Among these, one GGPPS gene was identified from C. reinhardtii, two from S. bicolor and P. patens, three from S. moellendorfii and M. truncatula, four from Z. mays and V. vinifera, five from T. cacao, six from S. tuberosum, seven from G. max and P. taeda, eight from O. sativa, 10 from G. arboreum, and G. raimondii, 12 from Arabidopsis, 25 from B. napus, G. barbadense and G. hirsutum. It is observed that from 18 species, GGPPS genes range from 1 (C. reinhardtii) to 25 (G. hirsutum and B. napus) indicating that GGPPS gene family underwent expansion during the evolution in land plants. Further, G. barbadense and G. hirsutum contained maximum (25) number of GGPPS genes among four cotton species, indicating the polyploidization and duplication effect on GhGGPPS gene family in G. barbadense and G. hirsutum.

Evolutionary analysis of GGPPS genes

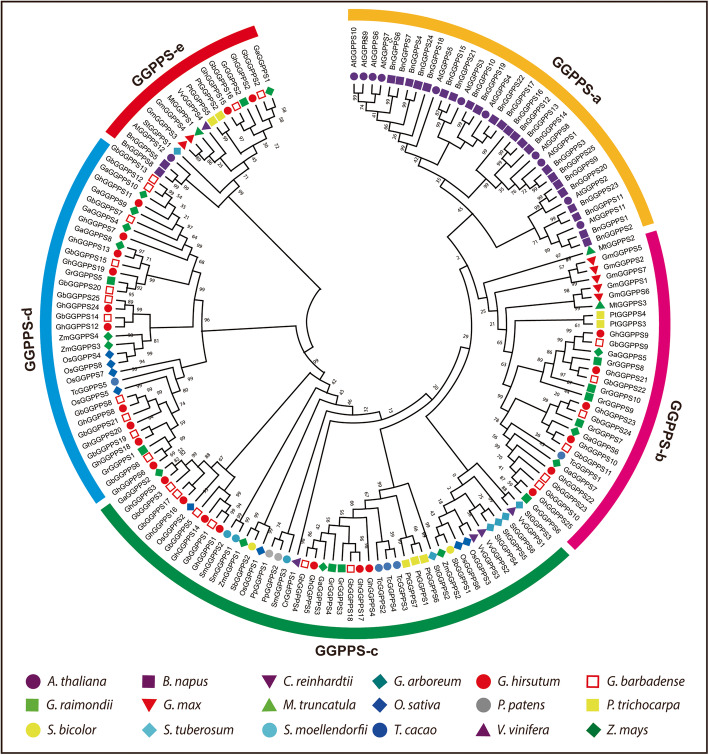

Next, we investigated the evolutionary relationships among 159 GGPPS genes of all observed plant species to assume evolutionary mechanisms leading to the formation and maintenance of multiple gene copies within them. The evolutionary analysis divided the GGPPS genes into five main groups, referred to as GGPPS-a to GGPPS-e (Fig. 1). Group GGPPS-c with maximum number (45 genes) of GGPPS family genes from fourteen species while group GGPPS-e with minimum number (16 genes) of GGPPS genes from 11 species except S. bicolor, S. moellendorfii, P. patens, C. reinhardtii, Z. mays, O. sativa, and T. cacao. Moreover, group GGPPS-b contained 30 genes from eight species including G. max, P. taeda, G. barbadense, M. truncatula, T. cacao, G. arboreum, G. raimondii, and G. hirsutum while, group GGPPS-a contained 34 genes from 2 species including Arabidopsis, and B. napus demonstrating a close relationship of these two species. Similarly, Group GGPPS-d contained 34 genes from seven species including O. sativa, Z. mays, T. cacao, G. barbadense, G. arboreum, G. raimondii, and G. hirsutum. Interestingly, 159 GGPPS genes from 18 species were randomly distributed to all groups, and most orthologous and paralogous genes between allotetraploids and diploids were clustered close to each other in the same group, showing the expansion and evolutionary relationship of the GGPPS gene family. The phylogenetic analysis showed that group GGPPS-c contained one GGPPS gene from first land plant green algae indicating that GGPPS gene family is derived from common ancestor, which is in agreement with earlier studies that all trans-isoprenyl diphosphate synthases are derived from a common ancestor [22, 23]. Similarly, group GGPPS-c also contained two genes from moss and three genes from fern, the more number of GGPPS genes from moss and fern than algae indicating that the GGPPS genes expanded in plant species during evolution by duplication event. Group GGPPS-a, b, d and e contained GGPPS genes from gymnosperms and angiosperms but not from algae, moss and fern, indicating that these groups might be evolved after separation of algae, ferns and moss. However, GGPPS genes from G. hirsutum were present in almost all groups except GGPPS-a. Furthermore, the increase in the predicted number of GGPPSs in G. hirsutum than G. arboreum and G. raimondii demonstrated duplication events during polyploidization. Moreover, the GGPPS genes from cotton showed close relationship with cacao GGPPS genes in phylogenetic tree, as well as their number and distribution differ in all groups (Fig. 1). For instance, in group GGPPS-c, GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS17, GbGGPPS18, GrGGPPS3, GrGGPPS4, GaGGPPS3, GhGGPPS5, and GbGGPPS4, genes showed a close relationship with three cacao genes (TcGGPPS2, TcGGPPS4 and TcGGPPS3), supporting the hypothesis that cacao and cotton were closely related and probably derived from the same ancestors [24]. Additionally, the results of phylogenetic analysis were also verified by constructing another phylogenetic tree using ME (Maximum evolution) method (Additional file 6:Fig. S1). Both phylogenetic trees displayed highly similar results.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary relationship among 159 GGPPS genes from 18 plant species. Prefixes At, Os, Sb, Gm, Sm, Pp, Cr, Zm, Pt, Vv, St, Mt, Bn, Tc, Ga, Gr, Gb, and Gh were used to recognize the GGPPS genes from Arabidopsis, O. sativa, S. bicolor, G. max, S. moellendorfii, P. patens, C. reinhardtii, Z. mays, P. taeda, V. vinifera, S. tuberosum, M. truncatula, B. napus, T. cacao, G. arboretum, G. raimondii, G. barbadense, and G. hirsutum respectively

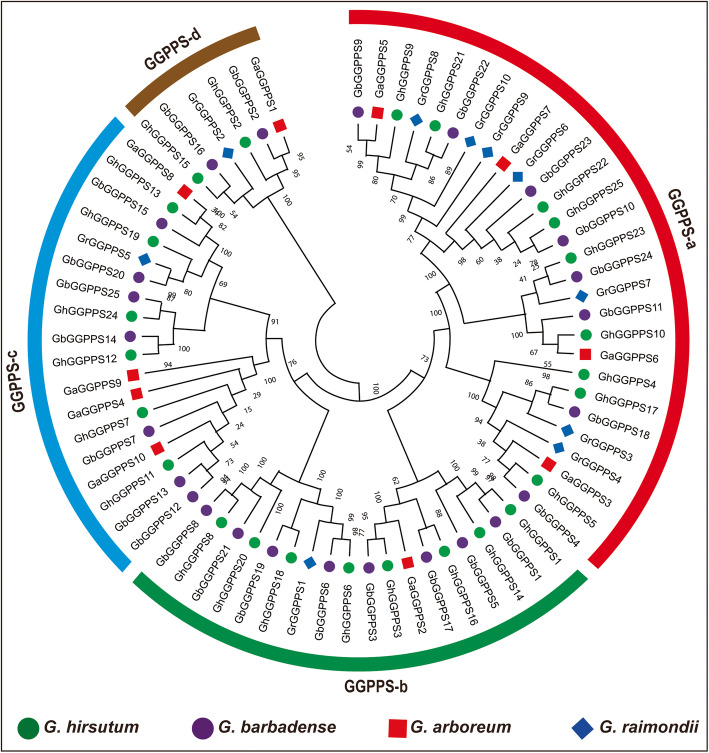

Next, we generated another phylogenetic tree among four cotton species by NJ (neighbor-joining) method. Phylogenetic tree divided 70 cotton GGPPS genes into four groups from GGPPS-a to GGPPS-d (Fig. 2). Group GGPPS-a was the biggest group with 28 members while group GGPPS-d was the smallest group with six members of GGPPS genes. Out of 70 cotton GGPPS genes, six GGPPS genes (GaGGPPS1, GbGGPPS2, GhGGPPS2, GrGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, and GhGGPPS15,) form a separate group in the phylogenetic tree indicating that GbGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, GhGGPPS2 and GhGGPPS15 are the orthologs of GaGGPPS1 and GrGGPPS2 and demonstrating that GbGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, GhGGPPS2 and GhGGPPS15 might be evolved as the result of hybridization of GaGGPPS1 and GrGGPPS2 during evolution. However, GhGGPPS genes form three groups with GGPPS-a as a largest group (11 genes) followed by GGPPS-c (four genes) and GGPPS-b (ten genes), when another phylogenetic tree (NJ) was constructed among them (Additional file 7: Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of GGPPS genes in G. arboreum, G. barbadense, G. hirsutum, and G. raimondii. The different color indicated different groups of GGPPS gene family

Biophysical properties and sequence logos of GGPPS in G. hirsutum

To explore the important characteristics of 25 members of GGPPS gene family in G. hirsutum, chemical and biophysical properties were predicted including chromosomal position (start and end points), gene length (bp), coding sequence (CDS), protein length (aa), molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). The gene length ranged from 620 to 6749 bp. Eleven genes with no introns exhibited the lower gene length ranged from 620 to 1118 bp, While two genes (GhGGPPS6 and GhGGPPS18) with 12 numbers of introns showed maximum gene length (6749 bp and 6657 bp) compared with others (Additional file 2: Table S2) indicating that increase in number of introns increases gene length. GhGGPPS14 and GhGGPPS20 as the most shortest and longest genes respectively, their coding sequence (CDS), numbers of amino acids (aa), and molecular weights ranged from 621 to 1932 bp, 206–643 aa, 22,741–71,107 Da respectively. The values of isoelectric point of GhGGPPS genes ranged from 4.67–9.68. Two proteins GhGGPPS7 (8.5) and GhGGPPS11 (9.68) showed isoelectric point more than 7, indicating that they were alkaline proteins, while all others showed isoelectric point below 7 indicating that they all were acidic proteins. In addition, the average hydropathy value of each residue present in the sequences was calculated to evaluate the GRAVY (Grand Average of Hydropathicity) values of the proteins. The positive GRAVY values of the proteins revealed hydrophobicity, however negative scores revealed hydrophilicity. According to the GRAVY values 14 GhGGPPS proteins were hydrophilic while 11 were hydrophobic (Additional file 2: Table S2). Subcellular localization prediction indicated that 12 GhGGPPS proteins were located in chloroplast, six in cytoplasm, two in mitochondrial, two in plasma membrane and three in nucleus.

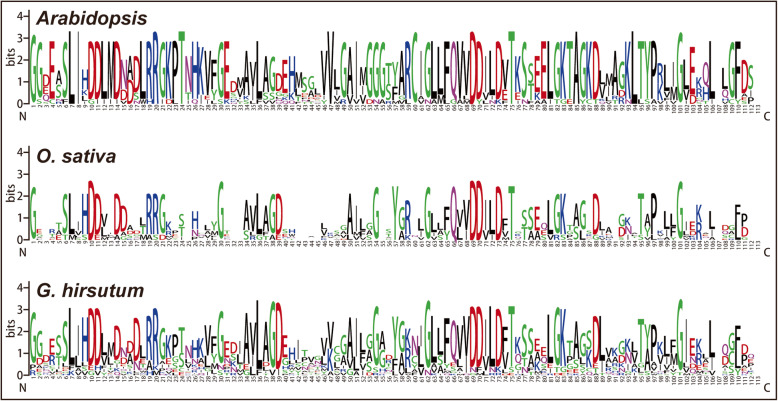

Furthermore, the GGPPS protein sequence logos could assist to discover and evaluate the pattern of GGPPS protein sequence conservation in other plant species, as sequence logos provide a more precise description of sequence similarity than consensus sequences. We generated the sequence logos of the conserved amino acid residues in Arabidopsis, rice and G. hirsutum to check whether the GGPPS family proteins were conserved in monocots and dicots during evolution (Fig. 3). Conserved amino acid residues analysis showed that the sequence logos among monocots and dicots are highly conserved across the N and C terminals.

Fig. 3.

Sequence logos of Arabidopsis, O. sativa, and G. hirsutum. The N-terminal and C-terminal of GGPPS gene domain are indicated by using ‘N’ and ‘C’

Intron/exon structure, protein motifs and promoter cis-elements of GhGGPPS genes

To further clarify the evolutionary relationships, gene structure and conserved motifs analysis of 25 GhGGPPS genes was performed (Additional file 8: Fig. S3a). The phylogenetic tree was build for gene structure and conserved motifs distribution analysis, which divided the G. hirsutum GGPPS genes into three groups on the basis of topology (bootstrap value and branch length) of phylogenetic tree. Results indicated that 10 conserved protein motifs were randomly distributed among 25 GhGGPPS genes (Additional file 8: Fig. S3b). Most of the GhGGPPS proteins displayed similar motifs distribution pattern, suggesting they might have conserved functions. Motif 4 was present in almost all proteins except three (GhGGPPS25, GhGGPPS15, and GhGGPPS2) GhGGPPS proteins. Motif 10 was identified only in seven proteins (GhGGPPS8, GhGGPPS20, GhGGPPS6, GhGGPPS18, GhGGPPS7, GhGGPPS12, and GhGGPPS24) of group GGPP-b, however it was not identified in proteins of groups GGPP-a and GGPP-c. Comparing to motif 10, motif 7 was not identified in group GGPP-b but in almost all proteins of groups GGPP-a and GGPP-c.

Gene structural analysis indicated that the coding regions of all GhGGPPS genes were interrupted by 1–12 introns. Accounting 44% (11GhGGPPS genes) of the total GhGGPPS genes, lack introns, and 8% (two GhGGPPS genes) had maximum number (12 introns) of introns. Two GhGGPPS genes (GhGGPPS3 and GhGGPPS16) were interrupted by only one intron. However, some variations of exon and intron sizes were observed between GhGGPPS gene family. In most cases, GhGGPPS genes within the same group exhibited similar gene structures in regard to the distribution patterns, number and length of introns/exons (Additional file 8: Fig. S3c).

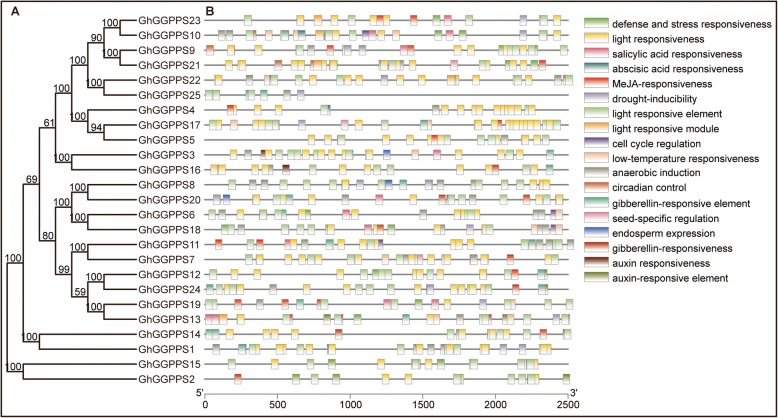

To analyze the possible roles of GhGGPPS genes in response to various conditions, promoters of candidate GhGGPPS genes were identified and searched for cis-elements. The GhGGPPS genes promoters shared light responsive boxes and stress-related boxes. Additionally, hormones-related cis-elements including MeJA, salicylic acid, gibberellin, auxin, and abscisic acid were also found in the GhGGPPS genes promoters (Fig. 4). Based on the results, we observed that stressed and hormones-related cis-elements were existed in almost all GhGGPPS genes. Some of the gene promoter regions contained various elements for plant growth and development including circadian, endosperm expression, cell cycle regulation, and seed specific regulation. The identified motifs showed that GhGGPPS genes may be regulated by various cis-elements within the promoter during growth and development.

Fig. 4.

Promoter cis-elements analysis of GhGGPPS genes. a Phylogenetic tree of 25 members of GhGGPPS gene family. b GhGGPPS promoter cis-elements distribution and list of names of promoter cis-elements with different colors was given to recognize different promoter cis-elements

Chromosomal location, colinearity analysis and gene duplication of GhGGPPS

Chromosomal location of GhGGPPS genes were investigated on their corresponding chromosomes (At and Dt sub-genome chromosomes of G. hirsutum). The chromosomes distribution indicated that 23 genes out of 25 were unevenly distributed among 12 chromosomes while two genes (GhGGPPS11 and GhGGPPS25) were assigned to scaffolds. Uneven distribution of GhGGPPS genes on chromosomes suggested that genetic variation existed in the evolutionary process. Six chromosomes A01, A07, A08, A10, A11, and A13 from At sub-genome contained 12 genes and six chromosomes D01, D07, D09, D10, D11, and D13 from Dt sub-genome contained 11 genes (Additional file 9: Fig. S4). However there was no gene located on chromosome nine (A09) of At sub-genome as well as chromosome eight (D08) of Dt sub-genome. Six GhGGPPS genes GhGGPPS6, GhGGPPS7, GhGGPPS10, GhGGPPS18, GhGGPPS19, and GhGGPPS24 were located on six chromosomes of At /Dt sub-genome such as A07, A08, A11, D07, D09, and D13 respectively. Chromosomes A01 and D01from At /Dt sub-genomes have a higher number of GhGGPPS genes as compared to others.

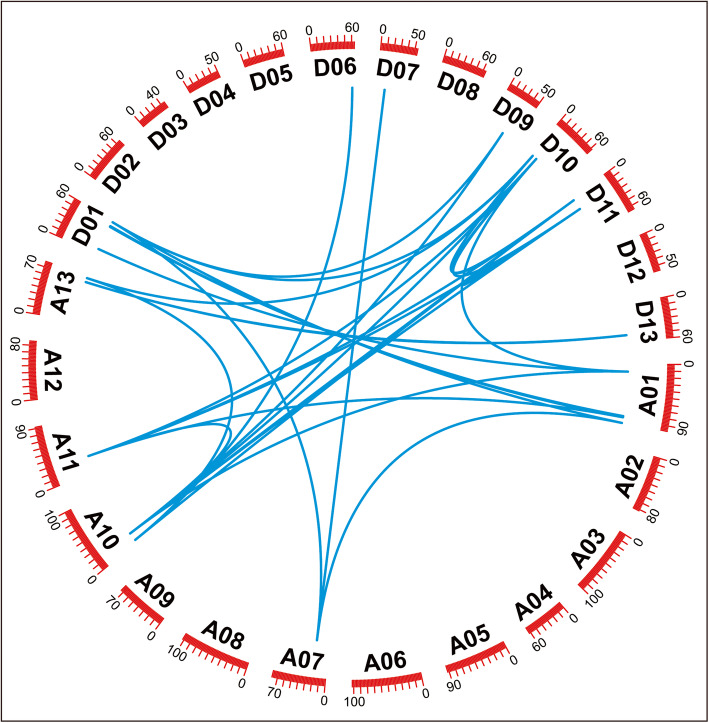

Collinearity analysis of GhGGPPS gene family indicated that there was 29 pairs of orthologous/paralogous GhGGPPS genes in G. hirsutum and that most of GhGGPPS genes loci were conserved for both sub-genomes (At and Dt) (Additional file 3: Table S3, Fig. 5). Tandem and segmental duplication events are the main causes of gene-family expansion in G. hirsutum. To understand the gene duplication event within the G. hirsutum genome, we determined the tandem and segmental duplication during the evolution of GGPPS gene family here. According to whole genome duplication analysis, it is observed that 22 pairs of GhGGPPS genes experienced segmental duplication while one tandem and two were dispersed duplication events, which suggested that segmental duplication contributed mainly in the expansion of the GGPPS family members in G. hirsutum genome (Additional file 3: Table S3).

Fig. 5.

Collinearity analysis of GhGGPPS genes. A01-A13 represented At sub-genomes chromosomes while D01-D13 represented Dt sub-genomes chromosome. The orthologous/paralogous gene pairs were specifying by blue color lines

Tissues specific expression of GhGGPPS genes

Spatiotemporal expression of transcript is mostly correlated with the biological function of gene. To investigate the tissue specific expression patterns of different GhGGPPS genes, RNA-seq data were downloaded from NCBI to generate heat map (Additional file 4: Table S4). We noted that all the genes were clustered according to their expression patterns in the vegetative organs (root, stem, and leaf), reproductive organs (torus, petal, stamen, pistil, and calycle), ovules (− 3, − 1, 0, 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 25 and 35 DPA) and fibers (5, 10, 20, and 25 DPA) (Additional file 10: Fig. S5). According to the heat map all genes exhibited ubiquitous expression with no specific pattern. However, six genes (GhGGPPS2, GhGGPPS15, GhGGPPS8, GhGGPPS22, GhGGPPS3, and GhGGPPS16) showed higher expression in almost all vegetative, reproductive, ovule, and fiber tissues. In contrast, seven genes (GhGGPPS11, GhGGPPS19, GhGGPPS5, GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS17, GhGGPPS7, and GhGGPPS14) showed very low expression in vegetative, reproductive, ovule and fiber tissues indicating that these genes were pseudo genes or could function with low transcripts in cotton development.

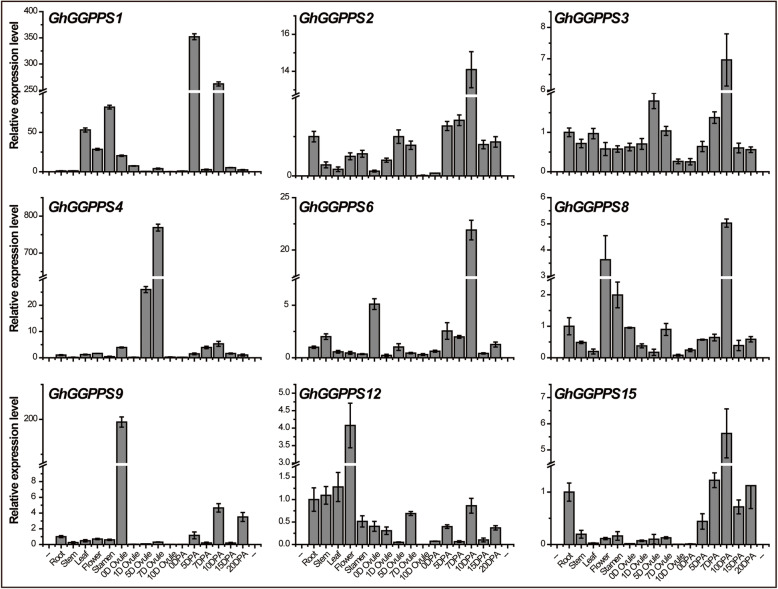

The different members of the same gene family can play different physiological functions by exhibiting their expression in different tissues/organs [25]. In earlier study, different expression pattern of GGPPS genes was observed in different organs and seedlings of A. thaliana [4]. To elucidate the roles of GhGGPPS genes in different tissues of upland cotton, 9 segmentally duplicated GhGGPPS genes were selected for qRT-PCR. Transcript level of GhGGPP4 and GhGGPPS9 showed significant and specific higher in primary developmental ovules from 0 to 7 DPA, indicating their potential roles in earlier development of ovule and the fiber cell initiation. Others like GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS6 and GhGGPPS15 showed higher expression in later development stages of fiber, indicating that they might have important participation in fiber elongation and secondary cell deposition. GhGGPPS2, GhGGPPS3 and GhGGPPS8 showed conserved expression in almost all tissues, indicating they may play some conserved and basic roles in plant different development stages. Whereas expression profiles in non-reproductive tissues of GhGGPPS12 indicated its potential roles in vegetative development (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Expression patterns of GhGGPSgenes in different tissues of G. hirsutum. qRT-PCR analysis was performed for nine segmentally duplicated GhGGPPS genes. Plant tissues were collected at different developmental stages such as root, stem, leaf, flower, stamen, 0, 1, 5, 7, and 10 DPA ovule tissues as well as 0, 5,7, 10, 15, and 20 DPA fiber tissues

Expression pattern of GhGGPPS gene family under abiotic and hormonal stresses

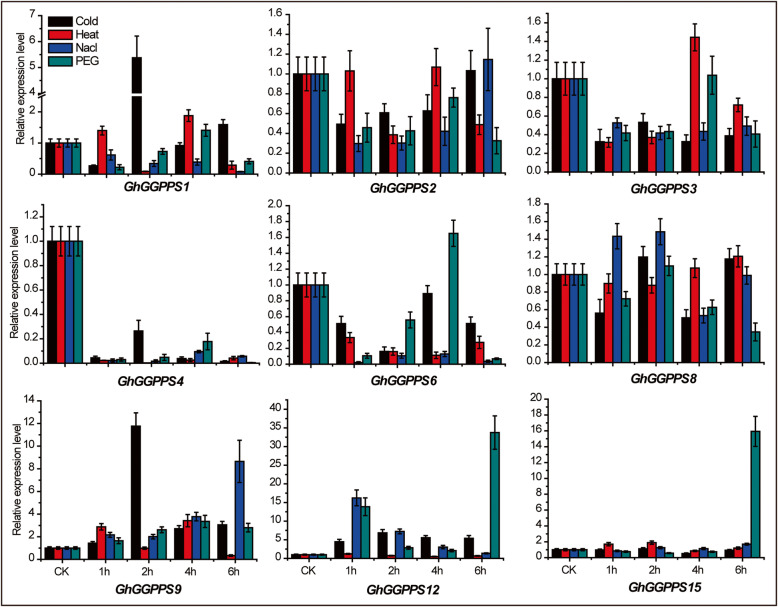

To further investigate the physiological and functional significance of GhGGPPS genes, we investigated the expression patterns of GhGGPPS genes under different stresses such as Cold, NaCl, PEG, and heat and hormonal treatments such as brassinolide (BL), gibberellins (GA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), salicylic acid (SA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Firstly, the expression pattern of GhGGPPS genes under abiotic stresses were analyzed by RNA-seq data downloaded from NCBI, and a heat map was generated. Results depicted that the expression of GhGGPPS genes were up or down-regulated under different treatments and that all the genes were clustered according to their different responses (Additional file 11: Fig. S6). GGPPS10, GGPPS23, GGPPS12, GGPPS24, GGPPS9, GGPPS3, and GGPPS22 were up-regulated with almost all abiotic stresses. To confirm that, qRT-PCR was performed for 9 selected GhGGPPS genes under different abiotic stresses including Cold, NaCl, PEG, and heat. qRT-PCR results revealed that GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS9, and GhGGPPS8 responded to almost all abiotic stresses. Whereas, the transcript level of GhGGPPS1 and GhGGPPS9 was up-regulated about 5 and 11 folds under 2 h cold stress respectively than that of control, while the transcript level of GhGGPPS8 was up-regulated 0.5 folds under 1 and 2 h NaCl stress suggesting that these genes might play an important positive role in cold and NaCl stresses. But the 33 and 15 folds up-regulated transcript level of GhGGPPS12 and GhGGPPS15 respectively were perceived at 6 h drought stress, indicating their specific and positive role in drought stress. Interestingly, the expression of GhGGPPS4 was down-regulated to no more than 30% of the transcripts in mock in response to all given abiotic stresses, as well as expression of GhGGPPS3 was down-regulated to about half level comparing to mock, indicating that both GhGGPPS4 and GhGGPPS3 are negative regulators of abiotic stresses in cotton (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression patterns of GhGGPPS genes under various abiotic stresses at different time points. The relative expression was normalized to the CK (0 h) whereas error bars represented the standard deviation (SD) of three replicates

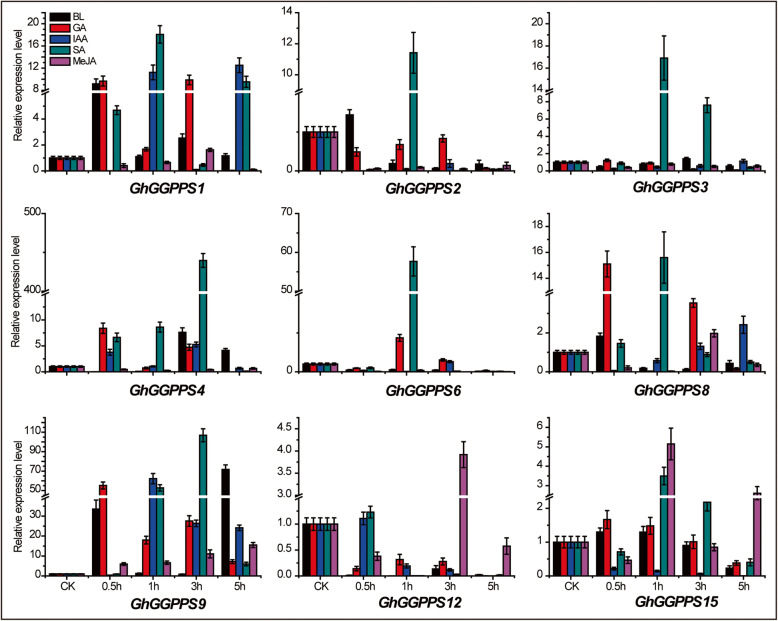

Secondly, we investigated the expression patterns of these genes under different hormonal treatments (BL, GA, IAA, SA and MeJA). qRT-PCR results indicated that GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS9, and GhGGPPS15 were up-regulated with all hormonal stresses with different time point, demonstrating that these genes are involved in all five hormonal signaling pathways (Fig. 8). GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS2, GhGGPPS3, GhGGPPS6, and GhGGPPS8 were preferentially up-regulated with 1 h SA and 0.5 h GA treatments. In addition, the up-regulated expression of GhGGPPS4 and GhGGPPS9 was observed when subjected to 3 h SA stress. The up-regulated transcript level of GhGGPPS12 and GhGGPPS15 were detected at 3 and 1 h after MeJA treatment respectively, proposed that these two genes are important for MeJA signaling.

Fig. 8.

Relative expression patterns of GhGGPPS genes with five hormonal (BL, GA, IAA, SA, and MeJA) stresses at different time points

Discussion

Most of the essential plant isoprenoids are derived from allylicprenyl diphosphates farnesyl-PP (FPP) and geranylgeranyl-PP (GGPP) [26]. GGPP is essential for primary and secondary isoprenoid compounds synthesis, however complete characterization of the GGPPS gene family was reported only in A. thaliana [4]. To fully understand the role of GhGGPPS isozymes in G. hirsutum, a complete characterization of this type of enzyme class was crucial. G. hirsutum is one of the most widely cultivated cotton specie that accounts for more than 90% of the world cotton fiber yield [27]. In this study, we analyzed the evolutionary relationships of GGPPS gene family in 18 plant species and characterized the biophysical properties, chromosomal location, gene duplication, selection pressure and expression in different plant tissues and responses to various abiotic and hormone stresses in G. hirsutum GGPPS gene family. The GGPPS genes in allotetraploid cotton (G. hirsutum) were focused to understand the roles of GGPPS gene family in cotton development.

Evolutionary characteristic of GGPPS gene family

During the identification of GGPPS gene family members in different plant species, only one GGPPS gene was identified in algae indicating that the plant-specific GGPPS genes might have originated from a common ancestor of land plants green algae (Additional file 5:Table S5). Interestingly, the number of GGPPS genes identified in G. hirsutum were more than double of the GGPPS genes identified in G. arboreum and G. raimondii, possibly because of its formation as an allotetraploid following hybridization of A and D genome progenitors [28, 29]. Phylogenetic tree divided the 159 GGPPS genes into five groups GGPPS-a to GGPPS-e, where group GGPPS-c was the biggest group while GGPPS-e was the smallest group with minimum number of GGPPS genes. Group GGPPS-c contained GGPPS genes from 14 species out of 18 along with one GGPPS gene from first land plant algae (C. reinhardtii) indicating that it was the oldest group evolved from the common ancestor and that GGPPS genes might have originated from a common ancestor of land plants as proved in previous studies [22, 23]. These findings were also supported by the analysis of conserved amino acid residues of G. hirsutum, O. sativa and A. thaliana. These results demonstrated that sequence logos were significantly conserved across N and C terminals of monocotyledons and dicotyledons plant species, exhibiting that GGPPS gene family remained conserved during evolutionary process. Moreover, the phylogenetic tree revealed that GGPPS genes from four cotton species showed more close relationship with cacao genes and predicted that cotton and cacao are evolved from common ancestors as proved from previous studies [24]. Additionally, NJ tree validation by ME tree showed the similar results including number of groups as well as positions of genes in groups.

To enhance the understanding of GGPPS gene family diversification during the history of evolution and domestication, a phylogenetic analysis was performed among G. barbadense, G. arboreum, G. raimondii, and G. hirsutum. Phylogenetic tree represented that group GGPP-a was the biggest group while GGPPS-d was the smallest. Group GGPPS-d had six GGPPS genes (GaGGPPS1, GbGGPPS2, GhGGPPS2, GrGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, and GhGGPPS15,), one from G. arboreum and G. raimondii while two from G. hirsutum and G. barbadense indicating that GbGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, GhGGPPS2 and GhGGPPS15 are the orthologs of GaGGPPS1 and GrGGPPS2. These results also represented that GbGGPPS2, GbGGPPS16, GhGGPPS2 and GhGGPPS15 might be evolved from the hybridization of GaGGPPS1 and GrGGPPS2 and further supported that G. arboreum and G. raimondii is the donor species of A-subgenome and D-subgenome, respectively. To understand the evolution relationship in detail, a phylogenetic tree among G. hirsutum GGPPS genes was constructed and it divided the 25 GhGGPPS genes into three groups. The GhGGPPS genes showing close evolutionary relationship were clustered together in phylogenetic tree, suggesting that they might play similar functions in plant growth and development.

Deeper analysis of GhGGPPS genes indicated that gene length of GhGGPPS genes increased with the increase of introns/gene ranging from 0 to 12 introns/genes with the gene length of 620–6749 bp. Further, it has been found that GhGGPPS belonging to the same group share similar exon-intron structures and protein motif distribution pattern along with some conserved motifs, indicated that GhGGPPS gene family is more conserved. Here, we also speculated that the encoded proteins with similar motifs might be associated with particular functions related to growth, development and stress tolerance in cotton. GhGGPPS20 is the largest presumed protein (71,107 Da), while GhGGPPS14 is the gene with smallest molecular weight (22,741 Da). Further, 14 GhGGPPS proteins were hydrophilic while11 proteins were hydrophobic and they were found to be localized in different cell organelles, such as chloroplast, mitochondria, plasma membrane and nucleus.

Gene duplications among GhGGPPS genes

Orthologs are genes that were derived from the same ancestral gene; encode proteins with similar biological functions, whereas paralogs are from a single gene as a result of duplication event, encode proteins with different functions [30, 31]. It is found that duplicated genes are mostly involved in the formation of paralogous genes present in gene families. Uneven gene distribution of GhGGPPS genes on the chromosomes of At and Dt sub-genome indicated that GhGGPPS genes experienced gene duplication events during evolution and hybridization. The At and Dt sub-genome donors (G. arboreum and G. raimondii, respectively) of upland cotton are close relatives sharing the same number of orthologs and doubling numbers of GGPPS genes in upland cotton. In this study, 70 identified GGPPS genes in four representative cotton species were used to further explore the evolution of the GGPPS family.

Additionally, colinearity analysis exhibited that 29 pairs of orthologous/paralogous GhGGPPS genes were identified in present study as a result of gene duplication. Deeper investigations showed that 22 (88%) GhGGPPS genes out of 25 originated from segmental duplication and 1 gene (4%) originated from tandem duplication; revealed high segmental and low tandem duplication events in GhGGPPS genes. Many gene families underwent segmental duplication and attributed the gene family expansion and functional divergence in cotton [32–35]. Here, both tandem and segmental duplications contributed to the expansion of GhGPPS gene family, but the segmental duplication might play a more critical role.

Expression profile analysis of GhGGPPS genes

Gene expressional patterns explain the functions of that gene in plant growth and development [36]. Our results indicated that promoter regions of GhGGPPS contained various elements related to plant growth and development including circadian, endosperm expression, cell cycle regulation, and seed specific regulation. Further, various cis-elements for different stress responses such as hormones (SA, ABA, GAs, auxin, and MeJA) and abiotic stress (low temperature and drought) were also identified. Cis-elements prediction results suggested that GhGGPPS genes might play important roles during stresses tolerance and in plant growth and development. So, to investigate the possible functions of GhGGPPS genes in cotton under different stresses and development, we analyzed the transcript level of nine selected GhGGPPS genes by qRT-PCR. The GhGGPPS genes showed different expression patterns, and the particular and up-regulated expression in ovule and fiber of some GhGGPPS (e.g. GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS9, and GhGGPPS15) genes indicated the important roles of these genes in ovule and fiber development (Fig. 6).

Previously, it has been reported that GGPPS genes functions were related to plant development, but the function of GGPPS genes under different stresses has not been reported yet. Thus, to find whether they might play some roles in stress response, the responses of GhGGPPS genes expression under various abiotic and hormonal treatments were determined. It was observed that most of the GhGGPPS genes were induced by different abiotic stresses, such as GhGGPPS1 and GhGGPPS9 were up-regulated under 2 h cold, GhGGPPS3 was up-regulated with 4 h heat, GhGGPPS8 was up-regulated under 1 and 2 h NaCl, and GhGGPPS15 was up-regulated by 6 h PEG treatment, indicating that GhGGPPS genes might positively participate in abiotic stress responses. However, the down-regulation of GhGGPPS4 in all the abiotic stresses indicated which may be very good target to improve the broad-spectrum abiotic tolerance of cotton by CRISPR-CAS9 gene editing technology. Next, four GhGGPPS genes (GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS9, and GhGGPPS15) were up-regulated with all hormonal stresses, whereas eight genes (GhGGPPS1, GhGGPPS2, GhGGPPS3, GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS6, GhGGPPS8, GhGGPPS9 and GhGGPPS15) were preferentially induced with SA stress at different time point. The up-regulated expression levels of two genes (GhGGPPS12 and GhGGPPS15) were detected at 3 and 1 h MeJA stress treatments, demonstrating the positive participation of GhGGPPS genes under hormonal stresses and their crucial roles in hormone signaling pathways.

Conclusions

Present work represents a genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of the GGPPS gene family in G. hirsutum. Segmental duplication was found as an important source for the expansion of the GGPPS gene family in cotton. Biophysical properties indicated that GhGGPPS genes localized to different cellular compartments, which suggested that the enzymes are associated with specific functions. Based on the abundance and spatiotemporal expression patterns of GhGGPPS genes transcripts, GhGGPPS genes showed associated with ovule and fiber development, and regulated by abiotic and hormonal stresses. Such as GhGGPPS4, GhGGPPS9 and GhGGPPS15 may be utilized well in the fiber yield and quality improvement, while GhGGPPS4 may be also a potential target of gene editing to enhance the plant abiotic tresses tolerance. The results provide useful information for further study related to structure, function and phylogenetic relationships of these gene family members and are helpful for the determination of key genes to improve stress tolerance and developmental research in cotton and other valuable plants.

Methods

Sequence identification

The AtGGPPS genes were used as queries to identify the GGPPS genes in other 17 plant species including O. sativa (version 10.0), S. bicolor (version 10.0), G. max (version 10.0), S. moellendorfii (version 1.0), P. patens (version 3.3), C. reinhardtii (version 5.5), Z. mays (version 10.0), P. taeda (version 1.0), V. vinifera (version 10.0), S. tuberosum (version 10.0), M. truncatula (version 10.0), B. napus (version 1.0), T. cacao (version 10.0), G. arboreum (ICR, version 1.0), G. raimondii (JGI, version 2.0), G. barbadense (NAU, version 1.1), and G. hirsutum (NAU, version 1.1) as described in previous study [37]. The Arabidopsis, cotton (G. arboreum, G. hirsutum, G. barbadense and G. raimondii) and other plant species databases were downloaded from TAIR 10 (http://www.arabidopsis.org), COTTONGEN (https://www.cottongen.org/) and Phytozome v11 (https://phytozome.jgi.%20doe.gov/pz/portal) respectively. The GGPPS protein sequences were confirmed by SMART [38], Interproscan 63.0 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/InterProScan/) [39] and hidden Markov model (HMM) as described previously [32].

Additionally, biophysical properties and subcellular localization was predicted by ExPASy-ProtParam tool (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html) and softberry (www.softberry.com) respectively.

Phylogenetic tree and sequence logos analysis

To construct a phylogenetic tree, GGPPS genes were aligned using “align by muscle” and tree was constructed using MEGA 7.0 with neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm and minimum evolution (ME) methods. The 1000 bootstrap replicates with 50% cutoff values were used and tree was then visualized by Tree View 1.6 (http://etetoolkit.org/treeview/).

Next, for sequence logos analysis, GGPPS proteins of A. thaliana, rice, and G. hirsutum were aligned by Clustal X 2.0 [40] and sequence logos were generated by WEBLOG [41] as described previously [42].

Intron/exon structure, protein motif distribution and promoter cis-elements analysis

GGPPS gene structure for all GhGGPPS genes was generated by Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) 2.0 [43]. For protein motifs, MEME program [44] was used as described previously [34]. 2.5-kb upstream sequence regions were used for GhGGPPS promoter cis-element analysis and cis-elements were analyzed in PlantCARE [45].

Chromosomal distribution, collinearity and transcriptomic data analysis

The position information of GhGGPPS genes on the chromosome were acquired from (https://cottonfgd.org/search) and physical locations on chromosomes was visualized by MapInspect (http://www.plantbreeding.wur.nl/UK/software_mapinspect.html) [46]. Colinearity analysis was performed by using methods described previously [47] and data obtained from MCScan was used in CIRCOS [48] to generate the figure.

For expression analysis, online available transcriptomic data (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4482290/) was used as described in previous studies [32, 34]. TopHat and cufflinks were used for RNA-seq expression analysis and the gene expressions were uniformed in fragments per kilo base million (FPKM) [49]. Genesis software was used to generate the heat map [50] of GGPPS genes.

Plant material, RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

The expression pattern of GhGGPPS genes in different tissues such as root, stem, leaf, flower, stamen, 0, 1, 5, 7, and 10 DPA ovule tissues as well as 0, 5, 7, 10, 15, and 20 DPA fiber tissues was estimated. These tissues were collected from ZM24 (also as CCRI24), a national certified specie of China (No. GS08001–1997) which was obtained from the Institute of Cotton Research, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and grown under field conditions in Zhengzhou China [51, 52]. Abiotic stresses such as cold (4 °C), heat (38 °C), NaCl (300 nmol L− 1), and PEG 6000 (10%) were applied for 1, 2, 4, 6 h with 3-leaf stage seedlings; hormonal treatments including BL (10 μM), GA (100 μM), IAA (100 μM), SA (10 μM) and MeJA (10 μM) were applied at 3-leaf stage for 0, 0.5, 1, 3 and 5 h. All samples RNA was extracted using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) and cDNA was synthesized by Prime Script® RT reagent kit (Takara, Dalian, China). SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara) was used for PCR amplifications and each assay contained three repeats. GhHis3 (Gene Bank, accession number AF024716) was used as an internal control [53] and calculations were carried out as described [54]. Primers used in this study were enlisted in Additional file 5: Table S5.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Renaming of GGPPS genes from 18 species. (ODS 14 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2. Prediction of biophysical properties of 25 GhGGPPS genes. (ODS 19 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3. Orthologous/paralogous gene pairs and gene duplication types of GhGGPPS gene family. (ODS 14 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S4. Transcriptomic data of tissue specific expression and abiotic stress responses of GhGGPPS gene family. (ODS 26 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S5. List of primers for qRT-PCR. (ODS 13 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S1. Evolutionary relationship among 159 GGPPS genes from 18 plant species using maximum evolution method.

Additional file 7: Figure S2. Evolutionary relationship of 25 GGPPS genes in G. hirsutum. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA software.

Additional file 8: Figure S3. The gene structure analysis of GGPPS gene family in G. hirsutum. (A) The unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed based on the GhGGPPS domains. (B) GGPPS gene family conserved protein motifs distribution. To identify different protein motifs of GhGGPPS gene family numbers (1–10) and different colors were given. (C) GhGGPPS gene family exon–intron structure was obtained by using GSDS 2.0.

Additional file 9: Figure S4. The distribution of GhGGPPS genes on the chromosomes of At and Dt sub genome of G. hirsutum.

Additional file 10: Figure S5. Heat map of GhGGPPS genes under different abiotic stresses. The RNA-Seq expression profiles of G. hirsutum were used for relative expression levels of GhGGPPS genes, gene expression level depicted in different colors on the scale.

Additional file 11: Figure S6. Expression levels of GhGGPPS genes in 22 tissues of G. hirsutum. RNA-Seq expression profiles were used to generate the heat map through Genesis software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peng Huo and Xin Li (Zhengzhou Research Center, Institute of Cotton Research of CAAS, Zhengzhou) for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- NaCl

Sodium chloride

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- GA

Gibberellic acid

- IAA

Indole-3-acetic acid

- BL

Brassinolide

- MeJA

Methyl jasmonate

- SA

Salicylic acid

- DPA

Days post-anthesis

- μM

Micro-molar

- Mya

Million years ago

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

Authors’ contributions

ZW and FL designed the research project; FA, GQ, DY and YL performed the experiments and collected seed samples; ZW and LG analyzed and interpreted the data and methodology; FA, GQ, and ZW wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have read, edited, and approved the current version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Research Plan of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.31690093), the Creative Research Groups of China (31621005) and Zhengzhou University (32410196). The funding agencies played no part in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data used in this study are included in this article and additional files. Transcriptome data used for gene expression analysis is available in Additional file 4 Table S4 and could be downloaded from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4482290/. The Genome sequence and annotation datasets that supported our findings are available in:

A. thaliana: http://www.arabidopsis.org

COTTON: https://www.cottongen.org/

Other species: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/phytozome/

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Faiza Ali and Ghulam Qanmber contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Fuguang Li, Email: aylifug@caas.cn.

Zhi Wang, Email: wangzhi01@caas.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12864-020-06970-8.

References

- 1.Bouvier F, Rahier A, Camara B. Biogenesis, molecular regulation and function of plant isoprenoids. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44(6):357–429. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang P-H. Reaction kinetics, catalytic mechanisms, conformational changes, and inhibitor design for prenyltransferases. Biochemistry. 2009;48(28):6562–6570. doi: 10.1021/bi900371p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vranová E, Coman D, Gruissem W. Structure and dynamics of the isoprenoid pathway network. Mol Plant. 2012;5(2):318–333. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck G, Coman D, Herren E, Ruiz-Sola MA, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Gruissem W, et al. Characterization of the GGPP synthase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82(4–5):393–416. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Vandermoten S, Haubruge É, Cusson M. New insights into short-chain prenyltransferases: structural features, evolutionary history and potential for selective inhibition. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(23):3685–3695. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnuma S-i, Suzuki M, Nishino T. Archaebacterial ether-linked lipid biosynthetic gene. Expression cloning, sequencing, and characterization of geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(20):14792–14797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Y, Proteau P, Poulter D, Ferro-Novick S. BTS1 encodes a geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(37):21793–21799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandmann G, Misawa N, Wiedemann M, Vittorioso P, Carattoli A, Morelli G, et al. Functional identification of al-3 from Neurospora crassa as the gene for geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase by complementation with crt genes, in vitro characterization of the gene product and mutant analysis. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 1993;18(2–3):245–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Okada K, Saito T, Nakagawa T, Kawamukai M, Kamiya Y. Five geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthases expressed in different organs are localized into three subcellular compartments in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(4):1045–1056. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kainou T, Kawamura K, Tanaka K, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. Identification of the GGPS1 genes encoding geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthases from mouse and human. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-molecular and cell biology of. Lipids. 1999;1437(3):333–340. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hojo M, Matsumoto T, Miura T. Cloning and expression of a geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase gene: insights into the synthesis of termite defence secretion. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16(1):121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange BM, Ghassemian M. Genome organization in Arabidopsis thaliana: a survey for genes involved in isoprenoid and chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51(6):925–948. doi: 10.1023/A:1023005504702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu F, Suzuki K, Okada K, Tanaka K, Nakagawa T, Kawamukai M, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a novel geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase gene from Arabidopsis thaliana in Escherichia coli. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38(3):357–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhu X, Suzuki K, Saito T, Okada K, Tanaka K, Nakagawa T, et al. Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase encoded by the newly isolated gene GGPS6 from Arabidopsis thaliana is localized in mitochondria. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35(3):331–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang G, Dixon RA. Heterodimeric geranyl (geranyl) diphosphate synthase from hop (Humulus lupulus) and the evolution of monoterpene biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(24):9914–9919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904069106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flagel LE, Wendel JF, Udall JA. Duplicate gene evolution, homoeologous recombination, and transcriptome characterization in allopolyploid cotton. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senchina DS, Alvarez I, Cronn RC, Liu B, Rong J, Noyes RD, et al. Rate variation among nuclear genes and the age of polyploidy in Gossypium. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20(4):633–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shan X, Liu Z, Dong Z, Wang Y, Chen Y, Lin X, et al. Mobilization of the active MITE transposons mPing and pong in rice by introgression from wild rice (Zizania latifolia Griseb.). Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(4):976–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Rinehart JA, Petersen MW, John ME. Tissue-specific and developmental regulation of cotton gene FbL2A. Demonstration of promoter activity in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 1996;112(3):1331–1341. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du X, Huang G, He S, Yang Z, Sun G, Ma X, et al. Resequencing of 243 diploid cotton accessions based on an updated a genome identifies the genetic basis of key agronomic traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50(6):796. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin D, et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492(7429):423. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chen A, Dale Poulter C, Kroon PA. Isoprenyl diphosphate synthases: protein sequence comparisons, a phylogenetic tree, and predictions of secondary structure. Protein Sci. 1994;3(4):600–607. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tachibana A, Yano Y, Otani S, Nomura N, Sako Y, Taniguchi M. Novel prenyltransferase gene encoding farnesylgeranyl diphosphate synthase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon, Aeropyrum pernix: molecular evolution with alteration in product specificity. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(2):321–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F, Fan G, Wang K, Sun F, Yuan Y, Song G, et al. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum. Nat Genet. 2014;46(6):567–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Qiao L, Zhang X, Han X, Zhang L, Li X, Zhan H, et al. A genome-wide analysis of the auxin/indole-3-acetic acid gene family in hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Vranová E, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Gruissem W. AtIPD: a curated database of Arabidopsis isoprenoid pathway models and genes for isoprenoid network analysis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(4):1655–1660. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.177758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiwari SC, Wilkins TA. Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) seed trichomes expand via diffuse growing mechanism. Can J Bot. 1995;73(5):746–757. doi: 10.1139/b95-081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohel R. Genetic nomenclature in cotton. J Hered. 1973;64(5):291–295. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Fan G, Lu C, Xiao G, Zou C, Kohel RJ, et al. Genome sequence of cultivated upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278(5338):631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidelberg JF, Paulsen IT, Nelson KE, Gaidos EJ, Nelson WC, Read TD, et al. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion–reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(11):1118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ali F, QANMBER G, Li Y, Ma S, Lu L, Yang Z, et al. Genome-wide identification of Gossypium INDETERMINATE DOMAIN genes and their expression profiles in ovule development and abiotic stress responses. J Cotton Res. 2019;2(1):3.

- 33.Zhang B, Liu J, Yang ZE, Chen EY, Zhang CJ, Zhang XY, et al. Genome-wide analysis of GRAS transcription factor gene family in Gossypium hirsutum L. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.QANMBER G, Yu D, Li J, Wang L, Ma S, Lu L, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of Gossypium RING-H2 finger E3 ligase genes revealed their roles in fiber development, and phytohormone and abiotic stress responses. J Cotton Res. 2018;1(1):1.

- 35.Liu C, Zhang T. Expansion and stress responses of the AP2/EREBP superfamily in cotton. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niehrs C, Pollet N. Synexpression groups in eukaryotes. Nature. 1999;402(6761):483. doi: 10.1038/990025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qanmber G, Liu J, Yu D, Liu Z, Lu L, Mo H, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the PERK gene family in Gossypium hirsutum reveals gene duplication and functional divergence. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7):1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qanmber G, Ali F, Lu L, Mo H, Ma S, Wang Z, et al. Identification of histone H3 (HH3) genes in Gossypium hirsutum revealed diverse expression during ovule development and stress responses. Genes. 2019;10(5):355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(8):1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Yu D, Qanmber G, Lu L, Wang L, Zheng L, et al. GhKLCR1, a kinesin light chain-related gene, induces drought-stress sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62(1):63–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Jia J, Zhao P, Cheng L, Yuan G, Yang W, Liu S, et al. MADS-box family genes in sheepgrass and their involvement in abiotic stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Yang Z, Gong Q, Wang L, Jin Y, Xi J, Li Z, et al. Genome-wide study of YABBY genes in upland cotton and their expression patterns under different stresses. Front Genet. 2018;9:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Sturn A, Quackenbush J, Trajanoski Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(1):207–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Z, Ge X, Yang Z, Qin W, Sun G, Wang Z, et al. Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations in upland cotton cultivars. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Yang Z, Zhang C, Yang X, Liu K, Wu Z, Zhang X, et al. PAG1, a cotton brassinosteroid catabolism gene, modulates fiber elongation. New Phytol. 2014;203(2):437–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Wan Q, Guan X, Yang N, Wu H, Pan M, Liu B, et al. Small interfering RNAs from bidirectional transcripts of GhMML3_A12 regulate cotton fiber development. New Phytol. 2016;210(4):1298–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Qanmber G, Lu L, Liu Z, Yu D, Zhou K, Huo P,et al. Genome-wide identification of GhAAI genes reveals that GhAAI66 triggers a phase transition to induce early flowering. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:4721–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Renaming of GGPPS genes from 18 species. (ODS 14 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2. Prediction of biophysical properties of 25 GhGGPPS genes. (ODS 19 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3. Orthologous/paralogous gene pairs and gene duplication types of GhGGPPS gene family. (ODS 14 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S4. Transcriptomic data of tissue specific expression and abiotic stress responses of GhGGPPS gene family. (ODS 26 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S5. List of primers for qRT-PCR. (ODS 13 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S1. Evolutionary relationship among 159 GGPPS genes from 18 plant species using maximum evolution method.

Additional file 7: Figure S2. Evolutionary relationship of 25 GGPPS genes in G. hirsutum. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA software.

Additional file 8: Figure S3. The gene structure analysis of GGPPS gene family in G. hirsutum. (A) The unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed based on the GhGGPPS domains. (B) GGPPS gene family conserved protein motifs distribution. To identify different protein motifs of GhGGPPS gene family numbers (1–10) and different colors were given. (C) GhGGPPS gene family exon–intron structure was obtained by using GSDS 2.0.

Additional file 9: Figure S4. The distribution of GhGGPPS genes on the chromosomes of At and Dt sub genome of G. hirsutum.

Additional file 10: Figure S5. Heat map of GhGGPPS genes under different abiotic stresses. The RNA-Seq expression profiles of G. hirsutum were used for relative expression levels of GhGGPPS genes, gene expression level depicted in different colors on the scale.

Additional file 11: Figure S6. Expression levels of GhGGPPS genes in 22 tissues of G. hirsutum. RNA-Seq expression profiles were used to generate the heat map through Genesis software.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are included in this article and additional files. Transcriptome data used for gene expression analysis is available in Additional file 4 Table S4 and could be downloaded from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4482290/. The Genome sequence and annotation datasets that supported our findings are available in:

A. thaliana: http://www.arabidopsis.org

COTTON: https://www.cottongen.org/

Other species: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/phytozome/