Abstract

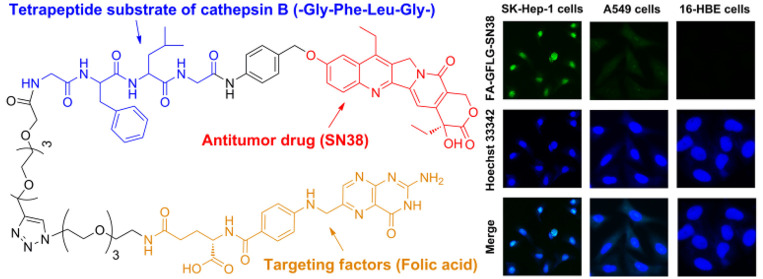

In this work, a folate receptor (FR)-mediated dual-targeting drug delivery system was synthesized to improve the tumor-killing efficiency and inhibit the side effects of anticancer drugs. We designed and synthesized an FR-mediated fluorescence probe (FA-Rho) and FR-mediated cathepsin B-sensitive drug delivery system (FA-GFLG-SN38). FA-GFLG-SN38 is composed of the FR ligand (folic acid, FA), the tetrapeptide substrate for cathepsin B (GFLG), and an anticancer drug (SN38). The rhodamine B (Rho)-labeled probe FA-Rho is suitable for specific fluorescence imaging of SK-Hep-1 cells overexpressing FR and inactive in FR-negative A549 and 16-HBE cells. FA-GFLG-SN38 exhibited strong cytotoxicity against FR-overexpressing SK-Hep-1, HeLa, and Siha cells, with IC50 values of 2–3 μM, but had no effect on FR-negative A549 and 16-HBE cells. The experimental results show that the FA-CFLG-SN38 drug delivery system proposed by us can effectively inhibit tumor proliferation in vitro, and it can be adopted for the diagnostics of tumor tissues and provide a basis for effective tumor therapy.

Keywords: Drug delivery system, folate receptor, cathepsin B, rhodamine B, SN38

Tumor tissues are distinguished from normal tissues by atypical growth, metabolic disorders, aberrant gene expression, and abnormal expression and activity of related enzymes in themselves and their surroundings.1 These characteristics lead to abnormal proliferation and metastasis and weaken the antitumor efficacy of conventional treatments.2 Ehrlich was the first to put forward the option of targeted drug therapy for improving the diagnosis and treatment of malignant tumors.3 An ideal drug delivery system distributes antitumor drugs specifically to target cells, tissues, or organs to achieve selective drug delivery, controlled release, and toxicity reduction.4,5 Tumor-receptor-mediated targeted therapies include those involving folate receptor (FR),6 epidermal growth factor receptor,7 sialic acid glycoprotein receptor,8 glycyrrhetinic acid receptor,9 and transferrin receptor systems.10 In contrast to the light expression in normal tissues, FR expression is over 2 orders of magnitude higher on the surface of tumor cells such as ovarian cancer and colon cancer cells.11 Folic acid (FA) was selected as the raw material for the synthesis of tumor-targeting drug delivery systems because of its characteristics of relatively low cost, nontoxicity, low immunity, stability, and and easy modification. Xu et al. prepared a glutathione-responsive prodrug based on FA and camptothecin (CPT) via disulfide bonds.12 The resulting FA–CPT prodrug showed higher specificity and cytotoxicity in FR-positive KB tumor cells compared with FR-negative A549 tumor cells. Therefore, the FR-mediated active drug delivery system could improve the cancer-targeting ability and reduce the side effects of anticancer drugs.13

7-Ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN38) is an active metabolite of irinotecan14 and also the substrate of P-glycoproteins, multidrug-resistance-associated proteins 2, and breast cancer resistance protein efflux pumps.15 SN38 exerts strong inhibitory activity on DNA topoisomerase I with cytotoxicity 100–1000 times greater than that of irinotecan,16 and it is used as an anticancer drug against malignant tumors in vitro,17 such as colorectal, lung, lymphoma, gastric, cervical, and ovarian cancers.18,19 However, its clinical application is limited by poor water solubility and instability.20 The water solubility of SN38 could be improved through several modifications, including liposome formulation,21 antibody–drug conjugates,22 and poly(ethylene glycol) functionalization.23 Currently, several delivery systems for irinotecan and its active metabolite SN38 have been developed, and the delivery system of liposome preparation SN38 (LE-SN38) has been studied in clinical trials.24 LE-SN38 was evaluated for mCRC following oxaliplatin progression in phase II studies, and the results showed that although LE-SN38 had acceptable toxicity, its therapeutic activity could not reach the prescribed criteria. Therefore, the development of an effective SN38 drug delivery system has important clinical significance.

Existing types of tumor microenvironment stimulation include responses to pH, reduction, oxidation, and enzymes.25−27 Tumor tissues generate abnormal expression or activity of specific enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases,28 cytosolic phospholipase A2,29 and cathepsin B (CTSB).30 CTSB has attracted extensive research attention in recent years as a potential marker for tumor screening and treatment target. The protease specifically hydrolyzes peptides such as Leu-Leu, Arg-Arg, Ala-Leu, Phe-Arg, Phe-Lys, Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly, Ala-Leu-Ala-Leu, etc.31,32 Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly (GFLG) is the most commonly used CTSB-responsive substrate among them. By leveraging of significant differences in the concentrations and activities of enzymes between tumor and normal tissues, effective enzyme-responsive antitumor drug delivery systems based on the high selectivity of enzymes can be developed.33

In order to improve the imaging method and tumor selectivity of treatment, we designed a FR-mediated dual-targeting delivery system that could target cancer cells more accurately. FA-N3 was coupled to form the ligand component of FR. The antitumor drug SN38, the tetrapeptide chain GFLG, and an oligo(ethylene glycol) tether were used to form the drug component. The ligand and drug underwent click reactions to generate the FA-GFLG-SN38 dual-targeted delivery system. Compared with SN38, our system has a number of advantages: (1) FA plays a targeting role in drug-specific guidance to FR-positive cancer cells;11 (2) CTSB, which is overexpressed in cancer cells, is used to release SN38 under conditions of weak acidity to improve the selectivity and reduce the side effects of the antitumor drug;30 (3) a relatively long oligo(ethylene glycol) tether increases the solubility of the drug, allowing longer circulation as a result of a reduction in renal clearance, enzymatic degradation, and immune cell recognition of the drug.23 We anticipated that SN38 would be inactive when linked to the FR-mediated delivery system. The FA-GFLG-SN38 drug delivery system binds to FR on the surface of cancer cells, and it is internalized into the cells via FR-mediated endocytosis. Then the drug is released via a 1,6-elimination process and becomes active within the cells when the C-terminus of the tetrapeptide chain (GFLG) in the system is cleaved by cancer cells overexpressing CTSB, thus resuming therapeutic activity. In addition, the FA-Rho fluorogenic probe without a CTSB-responsive tetrapeptide was prepared. Although the noncleavable conjugate is internalized into cells via FR-mediated endocytosis, rhodamine B (Rho) accumulates in lysosomes because of the lack of a tetrapeptidic substrate of CTSB. In the research described below, we synthesized and explored the effectiveness of the dual target delivery system. The results suggest that the new dual-target delivery system can indeed be used for selective killing or imaging of cancer cells.

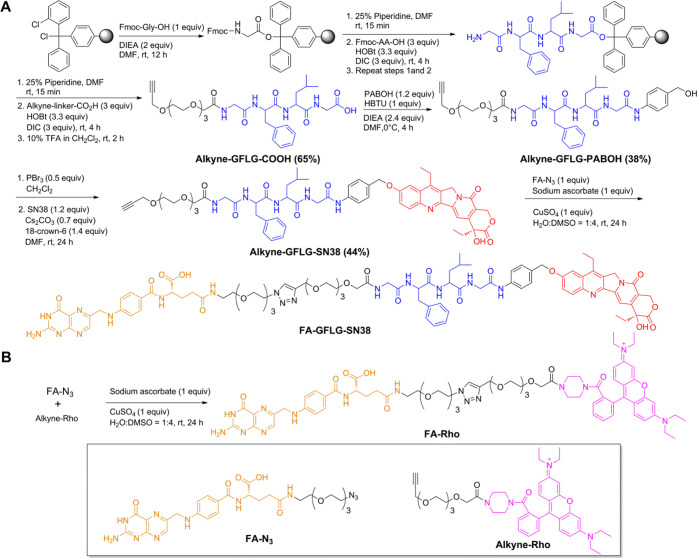

A schematic representation of the synthesis of FA-GFLG-SN38 is shown in Scheme 1A. The alkyne-linked peptide (alkyne-Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly) possessing a C-terminal hydrazide was assembled on a solid support in the presence of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), and N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC). Assembled alkyne-linked peptides were released from the solid support by treatment with 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in CH2Cl2. The alkyne-linked peptides and 4-aminobenzyl alcohol (PABOH) formed an amide group. Bromination of the hydroxyl group of alkyne-GFLG-PABOH followed by nucleophilic substitution and binding of SN38 yielded alkyne-GFLG-PAB-SN38. FA-γ-COOH had less steric hindrance compared to FA-α-COOH and could be selectively activated by controlling the molar ratio of FA and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC). FA-N3 was obtained via formation of an amide bond with NH2-linker-N3 at an FA:DCC ratio of 1:1.34 The resulting mixture was purified using semipreparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and lyophilized. The retention time of FA-N3 on analytical RP-HPLC was 19.2 min, and comparison of peak areas disclosed 74.58% FA γ-coupling. The alkyne-GFLG-SN38 was reacted with FA-N3 under click conditions (CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate), and the product was purified by semipreparative HPLC and lyophilized. The retention time of FA-GFLG-SN38 was 25.44 min on analytical RP-HPLC.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of (A) FA-GFLG-SN38 and (B) FA-Rho.

The synthetic pathway of FA-Rho is presented in Scheme 1B. Alkyne-Rho was reacted with FA-N3 under click conditions (CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate). The resulting mixture was purified with semipreparative RP-HPLC and lyophilized. The retention time of FA-Rho was 26.5 min on RP-HPLC.

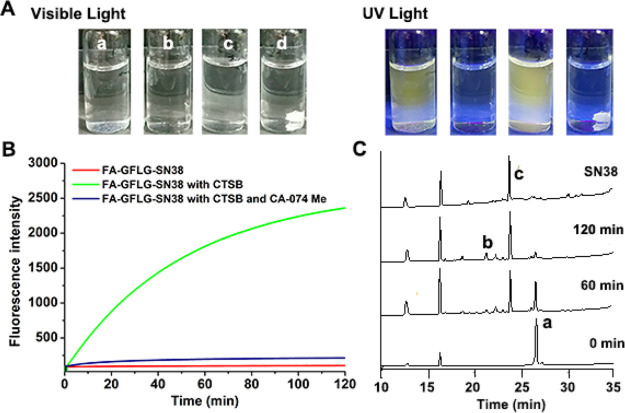

In order to verify whether FA-GFLG-SN38 is responsive to CTSB, we applied fluorescence spectroscopy to detect the fluorescence changes of FA-GFLG-SN38 in the presence of CTSB. As shown in Figure 1A, free SN38 showed yellow native fluorescence under UV irradiation, whereas FA-GFLG-SN38 displayed no fluorescence because of quenching of the SN38 fluorescence through binding with other conjugates. Treatment of FA-GFLG-SN38 with CTSB at 37 °C was characterized using fluorescence spectroscopy (Figure 1B). The fluorescence signal was not enhanced in the absence of CTSB, confirming the obvious quenching of FA-GFLG-SN38. The fluorescence increased with time in CTSB solutions, which was caused by enzymatic cleavage of the GFLG tetrapeptide in FA-GFLG-SN38 and subsequent release of SN38 (λex = 365 nm, λem = 540 nm). In contrast, no increase in fluorescence was observed upon treatment of FA-GFLG-SN38 with CTSB in the presence of the inhibitor CA-074 Me. These findings indicate that the SN38 is inactive when linked to the delivery system and that its CTSB-triggered release from the FA-GFLG-SN38 restores its fluorescence and therapeutic activity.

Figure 1.

Release of the SN38 drug from FA-GFLG-SN38 promoted by CTSB. (A) Images of different solutions (a, SN38; b, FA-GFLG-SN38; c, FA-GFLG-SN38 with CTSB; d, FA-GFLG-SN38 with CTSB and CA-074 Me) under (left) visible-light and (right) UV irradiation. (B) Release of SN38 from FA-GFLG-SN38 monitored using a fluorometer (λex = 365 nm, λem = 540 nm). (C) Release of SN38 from FA-GFLG-SN38 in the presence of CTSB monitored using RP-HPLC (detection at 254 nm) and mass spectrometry (a, FA-GFLG-SN38; b, FA-linker-Gly-Phe-OH ([M + Na]+m/z = 1114.7); c, SN38).

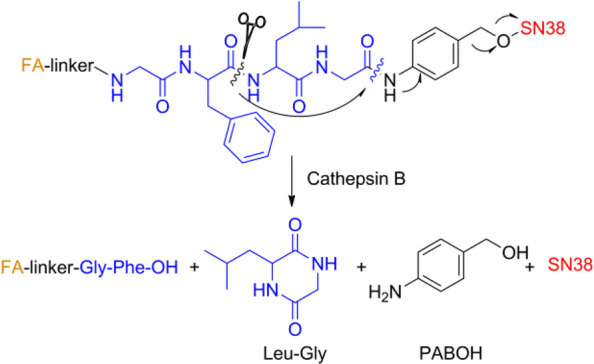

To further verify the CTSB-triggered release of SN38 from FA-GFLG-SN38, mixtures obtained from treatment of FA-GFLG-SN38 in the presence of CTSB were characterized and monitored using RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry. The results showed that SN38 (retention time = 23.6 min, [M + H]+m/z = 393.1) was efficiently released from FA-GFLG-SN38 (retention time = 26.4 min, [M + Na]+m/z = 1764.3) and produced along with FA-linker-Gly-Phe-OH (retention time = 21.4 min, [M + Na]+m/z = 1114.7) in the presence of CTSB (Figure 1C). Mixtures were further subjected to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, which revealed the presence of the cyclic dipeptide Leu-Gly (retention time = 34.0 min, [M + H]+m/z = 171.2). The tetrapeptidic substrate in FA-GFLG-SN38 was enzymatically hydrolyzed by CTSB into Gly-Phe and Leu-Gly, and the drug was released via a 1,6-elimination process when the C-terminus of the dipeptide (Leu-Gly) in the delivery system was cleaved (Scheme 2). The above observations demonstrate that FA-GFLG-SN38 is cleaved by CTSB to release FA-linker-Gly-Phe-OH, cyclic dipeptide (Leu-Gly), PABOH, and SN38.

Scheme 2. Cleavage of FA-GFLG-SN38 by CTSB.

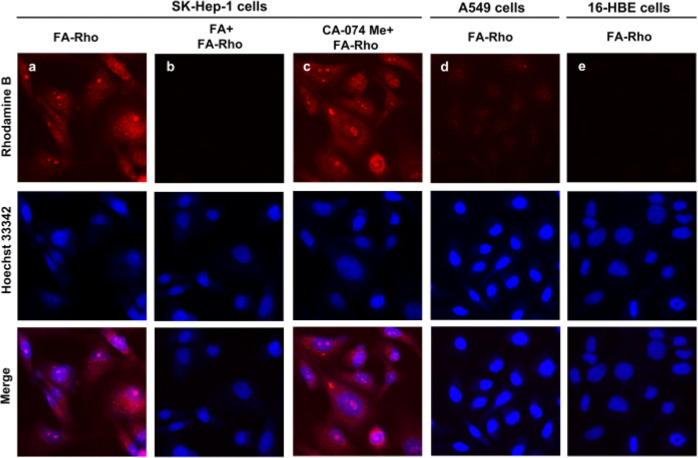

To determine the effect of FR specificity on the cellular internalization rate of the delivery system, we compared the fluorescence of SK-Hep-1, A549, and 16-HBE cells immediately after incubation with FA-Rho. Rhodamine B exhibits fluorescence in both its free and conjugated forms.35 It was expected that FA-Rho accumulation in cells would occur through FR-mediated endocytosis, followed by increased fluorescence emission in cells caused by rhodamine B localization.36 The results of confocal microscopy analysis of the treated SK-Hep-1 cancer cells show that a red fluorescence signal was detected mainly in the lysosomes (Figure 2). After preincubation with CA-074 Me (20 μM) and subsequent treatment with 5 μM FA-Rho, strong red fluorescence signals were observed in SK-Hep-1 cancer cells. However, when SK-Hep-1 cells were incubated with FA for 1 h and then treated with FA-Rho, the fluorescence signal associated with rhodamine B was attenuated. The results showed that rhodamine B was enriched in cells through endocytosis of FR. In addition, faint fluorescence was detectable in FA-Rho-treated A549 cancer cells and 16-HBE normal cells owing to low expression levels of FR. The above observations clearly suggest that FA-Rho enables selective fluorescence imaging of cancer cells through FR-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence imaging of cells treated with FA-Rho. (a–c) SK-Hep-1 cancer cells were incubated with (a) 5 μM FA-Rho for 24 h, (b) 3 mM FA for 1 h and then 5 μM FA-Rho for 24 h, and (c) 20 μM CA-074 Me for 24 h and then 5 μM FA-Rho for 24 h. (d) A549 cancer cells were incubated with 5 μM FA-Rho for 24 h. (e) 16-HBE normal cells were incubated with 5 μM FA-Rho for 24 h. Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL) was used to stain the nuclei. The incubated cells were imaged with confocal microscopy.

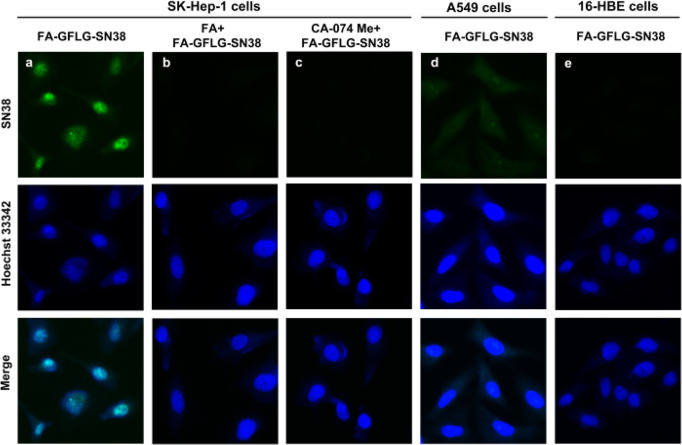

The usefulness of FA-GFLG-SN38 for fluorescence detection of cancer and normal cells was investigated. Unlike rhodamine B, the fluorescence of SN38 requires it to exist in its free or conjugated form. When the conjugated system is modified, the SN38-conjugate will be in its “Turn-OFF” state,37 but cleavage of its enzymatically cleavable group would transform the system into the “Turn-ON” state. We infer that if free SN38 is released from the FA-GFLG-SN38 binding under the action of lysosomal CTSB, it should accumulate in the nucleus of its action because of its fast diffusion kinetics.38 To probe the expectations, we compared the fluorescence of SK-Hep-1, A549, and 16-HBE cells immediately after incubation with 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38. As shown in Figure 3, strong green fluorescence was detected in nuclei of treated SK-Hep-1 cancer cells, indicating that released SN38 does indeed spread to and localize in the nucleus. However, when the SK-Hep-1 cancer cells were preincubated with 3 mM FA before treatment with 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38, the fluorescence intensity was significantly reduced. On the other hand, SK-Hep-1 cancer cells preincubated with CA-074 Me (20 μM) and subsequently treated with 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 exhibited faint fluorescence signals. The above results indicated that although FA-GFLG-SN38 was degraded in SK-Hep-1 cancer cells, in the presence of CA-074 Me, the coupling was not cleaved by intracellular cathepsin B to release free SN38. When A549 cells were incubated with FA-GFLG-SN38, faint fluorescence signals was observed in the lysosomes, similar to those promoted by incubation of mixtures of cancer cells with FA-Rho in the presence of FA. In addition, no fluorescence was detectable in FA-GFLG-SN38-treated 16-HBE normal cells because of the lack of FR. Taken together, the results show that both FR and CTSB activity are required for the release of free SN38 from FA-GFLG-SN38 in SK-Hep-1 cells, where it accumulates in the nucleus.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence imaging of cells treated with FA-GFLG-SN38. (a–c) SK-Hep-1 cancer cells were incubated with (a) 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 for 24 h, (b) 3 mM FA for 1 h and then 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 for 24 h, and (c) 20 μM CA-074 Me for 24 h and then 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 for 24 h. (d) A549 cancer cells were incubated with 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 for 24 h. (e) 16-HBE normal cells were incubated with 5 μM FA-GFLG-SN38 for 24 h. Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL) was used to stain the nuclei. The incubated cells were imaged with confocal microscopy.

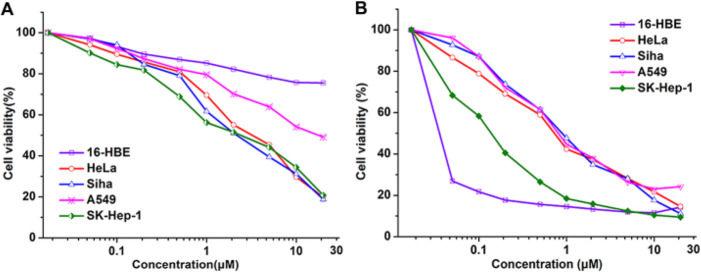

The antitumorigenic activity of FA-GFLG-SN38 was evaluated by measuring the viability of cancer (HeLa, Siha, A549, and SK-Hep-1) and normal (16-HBE) cells using the MTT assay (MTT = 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide). It is well-known that HeLa cells are FR-positive, while A549 cells are FR-negative.39,40 The results indicated that FA-GFLG-SN38 had a significant antitumorigenic activity against SK-Hep-1, HeLa, and Siha cells, with IC50 values of 2–3 μM (Figure 4A). FA-GFLG-SN38 reduced the cell viability of A549 cells by 51% under concentration of 20 μM, while that of 16-HBE normal cells at the same concentration decreased by 24%. The low toxicity of FA-GFLG-SN38 toward A549 and 16-HBE cells is due to the deficiency of FR, which is consistent with the described phenomenon of fluorescence imaging. These results indicate preferential activity of FA-GFLG-SN38 against FR-positive cells. Next, we examined the antiproliferative activity of free SN38 on cancer and normal cells. Free SN38 exhibited strong cytotoxicity against cancer and normal cells with IC50 values of 0.3–1 μM (Figure 4B). These results suggest that FA-GFLG-SN38 selectively targets cancer cells containing FR and CTSB and thus that FA-GFLG-SN38 could be used as an effective system for targeted therapy of tumor cells. The results show that both FR and CTSB activity are required for the release of free SN38 from FA-GFLG-SN38 in SK-Hep-1 cells, where it accumulates in the nucleus.

Figure 4.

Cancer and 16-HBE cells were incubated with various concentrations of (A) FA-GFLG-SN38 or (B) free SN38 for 72 h. Cell viability was measured with the MTT assay.

In summary, we have successfully developed two FR-mediated delivery systems. The FA-Rho probe is suitable for specific fluorescence imaging of SK-Hep-1 cancer cells overexpressing FR and usually inactive in FR-negative cells (A549 and 16-HBE cells). The FR-mediated cathepsin B-sensitive drug delivery system (FA-GFLG-SN38) is composed of the FR ligand folic acid (FA), the tetrapeptide substrate of cathepsin B (GFLG), and an anticancer drug (SN38). The experimental results showed that FA-GFLG-SN38 is an effective antitumorigenic agent. FA-GFLG-SN38 integrates features of enzymatically triggered drug release, fluorescence imaging, and targeted drug delivery into one system. Our preliminary studies suggest that SN38 is released from FA-GFLG-SN38 in the presence of CTSB and emits fluorescence, which can be effectively applied for cancer cells for overexpressing FR. The FA-GFLG-SN38 delivery system exhibited strong cytotoxicity against SK-Hep-1, HeLa, and Siha cells with IC50 = 2–3 μM but had no effect on FR-negative A549 and 16-HBE cells, thus minimizing the toxic side effects of the anticancer drug. On the basis of the collective findings, we propose that the newly developed dual-targeted drug delivery system provides an effective framework for future potential applications to tumor detection and targeted therapy in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 21462045 and 31760330).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FR

folate receptor

- FA

folic acid

- SN38

7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin

- CTSB

cathepsin B

- GFLG

Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly

- Rho

rhodamine B

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- DIEA

diisopropylethylamine

- PABOH

4-aminobenzyl alcohol

- DIC

N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- DCC

N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00031.

Experimental procedures, chemical characterization, biochemical methods, and additional data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Chen Z. H.; Yu Y. P.; Tao J.; Liu S.; Tseng G.; Nalesnik M.; Hamilton R.; Bhargava R.; Nelson J. B.; Pennathur A.; Monga S. P.; Luketich J. D.; Michalopoulos G. K.; Luo J. H. MAN2A1-FER Fusion Gene is Expressed by Human Liver and Other Tumor Types and has Oncogenic Activity in Mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1120–1132. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinskog E. S.; Sagstad S. J.; Wagner M.; Karlsen T. V.; Yang N.; Markhus C. E.; Yndestad S.; Wiig H.; Eikesdal H. P. Impaired Lymphatic Function Accelerates Cancer Growth. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 45789–45802. 10.18632/oncotarget.9953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich P. Die Behandlung der Syphilis mit dem Ehrlichschen Präparat 606. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1910, 36, 1893–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Meng L.; Lu Q.; Fei Z.; Dyson P. J. Targeted Delivery and Controlled Release of Doxorubicin to Cancer Cells Using Modified Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6041–6047. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang Q.; He X.; Chen H.; Zou Y.; Li Y.; Lin K.; Cai X.; Xiao J.; Zhang Q.; Cheng Y. Multifunctional Melanin-Like Nanoparticles for Bone-Targeted Chemo-Photothermal Therapy of Malignant Bone Tumors and Osteolysis. Biomaterials 2018, 183, 10–19. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péraudeau E.; Cronier L.; Monvoisin A.; Poinot P.; Mergault C.; Guilhot F.; Tranoy-Opalinski I.; Renoux B.; Papot S.; Clarhaut J. Enhancing Tumor Response to Targeted Chemotherapy Through Up-Regulation of Folate Receptor α Expression Induced by Dexamethasone and Valproic Acid. J. Controlled Release 2018, 269, 36–44. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooijen J. M.; Qiu S. Q.; Timmer-Bosscha H.; van der Vegt B.; Boers J. E.; Schröder C. P.; de Vries E. G. E. Androgen Receptor Expression Inversely Correlates with Immune Cell Infiltration in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 103, 52–60. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büll C.; Heise T.; Adema G. J.; Boltje T. J. Sialic Acid Mimetics to Target the Sialic Acid-Siglec Axis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 519–531. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S.; Li M.; Yu X.; Jin H.; Zhang Y.; Zhang L.; Zhou D.; Xiao S. Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of Water-Soluble β-Cyclodextrin-Glycyrrhetinic Acid Conjugates as Potential Anti-Influenza Virus Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 328–338. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons V. J.; Helms A.; Pappas D. The Effect of Protein Expression on Cancer Cell Capture Using the Human Transferrin Receptor (CD71) As an Affinity Ligand. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1076, 154–161. 10.1016/j.aca.2019.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M. F.; Jensen S.; Füchtbauer E. M.; Martensen P. M. High Folic Acid Diet Enhances Tumour Growth in PyMT-Induced Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 752–761. 10.1038/bjc.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Hou M.; Shi X.; Gao Y. E.; Xue P.; Liu S.; Kang Y. Rapidly Cell-Penetrating and Reductive Milieu-Responsive Nanoaggregates Assembled from an Amphiphilic Folate-Camptothecin Prodrug for Enhanced Drug Delivery and Controlled Release. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 444–454. 10.1039/C6BM00800C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom H. J.; Shaw G. M.; den Heijer M.; Finnell R. H. Neural Tube Defects and Folate: Case Far from Closed. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 724–731. 10.1038/nrn1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Zhu L.; Sheng C.; Yao J.; Miao Z.; Zhang W.; Wei Y.; Shi R. Synthesis and Biological Activities of Fluorinated 10-Hydroxycamptothecin and SN38. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014, 157, 48–51. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. K.; McLeod H. L. Lessons Learned from the Irinotecan Metabolic Pathway. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 41–49. 10.2174/0929867033368619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosallaei N.; Mahmoudi A.; Ghandehari H.; Yellepeddi V. K.; Jaafari M. R.; Malaekeh-Nikouei B. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Containing 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin (SN38): Preparation, Characterization, in vitro, and in vivo Evaluations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 104, 42–50. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Lu H.; Liao L.; Zhang X.; Gong T.; Zhang Z. Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin-Phospholipid Complex: in vitro and in vivo Studies. Drug Delivery 2015, 22, 701–709. 10.3109/10717544.2014.895069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M. H.; Peng C. L.; Yang S. J.; Shieh M. J. Photothermal, Targeting, Theranostic Near-Infrared Nanoagent with SN38 against Colorectal Cancer for Chemothermal Therapy. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 2766–2780. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C.; Wen S.; Zhang Q.; Zhu Q.; Yu J.; Lu W. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Paclitaxel and Camptothecin Prodrugs on the Basis of 2-Nitroimidazole. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 762–765. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B.; Desai A.; Tang S.; Thomas T. P.; Baker J. R. Jr. The Synthesis of a c(RGDyK) Targeted SN38 Prodrug with an Indolequinone Structure for Bioreductive Drug Release. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1384–1387. 10.1021/ol1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.; Wang S. Preparation, Pharmacokinetic Profile, and Tissue Distribution Studies of a Liposome-Based Formulation of SN-38 Using an UPLC-MS/MS Method. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 1450–1456. 10.1208/s12249-016-0484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.; Goetsch L.; Dumontet C.; Corvaïa N. Strategies and Challenges for the Next Generation of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16, 315–337. 10.1038/nrd.2016.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J.; Okeke C. I.; Hu Z. B.; Xu J. DSPE-PEG: a Distinctive Component in Drug Delivery System. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1598–1605. 10.2174/1381612821666150115144003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocean A. J.; Niedzwiecki D.; Atkins J. N.; Parker B.; O’Neil B. H.; Lee J. W.; Wadler S.; Goldberg R. M. LE-SN38 for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer after Progression on Oxaliplatin: Results of CALGB 80402. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4109–4109. 10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.4109.18757324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X.; Jiang Y.; Xiao Q.; Leung A. W.; Hua H.; Xu C. pH-Responsive Polymer-Drug Conjugates: Design and Progress. J. Controlled Release 2016, 222, 116–129. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W.; Li J.; Ke W.; Zha Z.; Ge Z. Integrated Nanoparticles to Synergistically Elevate Tumor Oxidative Stress and Suppress Antioxidative Capability for Amplified Oxidation Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 29538–29546. 10.1021/acsami.7b08347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L.; Xia S.; Wu K.; Huang Z.; Chen H.; Chen J.; Zhang J. A pH/Enzyme-Responsive Tumor-Specific Delivery System for Doxorubicin. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6309–6316. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant M.; Nagaraju G. P.; Rajitha B.; Lammata S.; Jella K. K.; Buchwald Z. S.; Lakka S. S.; Ali A. N. Matrix Metalloproteinases: Their Functional Role in Lung Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 766–780. 10.1093/carcin/bgx063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi B.; Jelcic M.; Niethammer P. The Cell Nucleus Serves as a Mechanotransducer of Tissue Damage-Induced Inflammation. Cell 2016, 165, 1160–1170. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobuzio-Donahue C. A.; Shuja S.; Cai J.; Peng P.; Murnane M. J. Elevations in Cathepsin B Protein Content and Enzyme Activity Occur Independently of Glycosylation During Colorectal Tumor Progression. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 29190–29199. 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D. S.; Johnson R. N.; Pun S. H. Cathepsin B-Sensitive Polymers for Compartment-Specific Degradation and Nucleic Acid Release. J. Controlled Release 2012, 157, 445–454. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B.; Chung D. E.; Warnecke A.; Fichtner I.; Kratz F. Albumin-Binding Prodrugs of Camptothecin and Doxorubicin with an Ala-Leu-Ala-Leu-Linker that are Cleaved by Cathepsin B: Synthesis and Antitumor Efficacy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 702–716. 10.1021/bc0602735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber S.; Baabur-Cohen H.; Blau R.; Epshtein Y.; Kisin-Finfer E.; Redy O.; Shabat D.; Satchi-Fainaro R. Polymeric Nanotheranostics for Real-Time Non-Invasive Optical Imaging of Breast Cancer Progression and Drug Release. Cancer Lett. 2014, 352, 81–89. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willibald J.; Harder J.; Sparrer K.; Conzelmann K. K.; Carell T. Click-Modified Anandamide siRNA Enables Delivery and Gene Silencing in Neuronal and Immune Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12330–12333. 10.1021/ja303251f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas S. C.; Gawas R. U.; Ghosh B. K.; Banerjee M.; Ganguly A.; Chatterjee A.; Ghosh N. N. Water-Dispersible Rhodamine B Hydrazide Loaded TiO2 Nanoparticles for “Turn On” Fluorimetric Detection and Imaging of Orthosilicic Acid Accumulation In-Vitro in Nephrotoxic Kidney Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 8142–8154. 10.1166/jnn.2018.16338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Lee C. H.; Shin I. Preparation of a Multiple-Targeting NIR-Based Fluorogenic Probe and Its Application for Selective Cancer Cell Imaging. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4628–4631. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmanpour M.; Yousefi G.; Samani S. M.; Mohammadi S.; Anbardar M. H.; Tamaddon A. Nanoparticulate delivery of Irinotecan Active Metabolite (SN38) in Murine Colorectal Carcinoma through Conjugation to Poly (2-ethyl 2-oxazoline)-b-poly (L-glutamic acid) Double Hydrophilic Copolymer. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 136, 104941. 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X.; Baek K. H.; Shin I. Dual-Targeting Delivery System for Selective Cancer Cell Death and Imaging. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 947–956. 10.1039/C2SC21777E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Shi X.; Hou M.; Xue P.; Gao Y. E.; Liu S. Y.; Kang Y. Disassembly of Amphiphilic Small Molecular Prodrug with Fluorescence Switch Induced by pH and Folic Acid Receptors for Targeted Delivery and Controlled Release. Colloids Surf., B 2017, 150, 50–58. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran S. Augmented Cytotoxic Effects of Paclitaxel by Curcumin Induced Overexpression of Folate Receptor-α for Enhanced Targeted Drug Delivery in HeLa Cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 56, 279–285. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.