Abstract

Since the 1990s, concerted attempts have been made to improve the efficiency of medicinal chemistry synthesis tasks using automation. Although impacts have been seen in some tasks, such as small array synthesis and reaction optimization, many synthesis tasks in medicinal chemistry are still manual. As it has been shown that synthesis technology has a large effect on the properties of the compounds being tested, this review looks at recent research in automation relevant to synthesis in medicinal chemistry. A common theme has been the integration of tasks, as well as the use of increased computing power to access complex automation platforms remotely and to improve synthesis planning software. However, there has been more limited progress in modular tools for the medicinal chemist with a focus on autonomy rather than automation.

Keywords: Automation, medicinal chemistry, synthesis, autonomy, artificial intelligence

The role of a medicinal chemistry department is to design and synthesize molecules in order to test hypotheses about factors such as activity, selectivity, metabolism, and excretion and to ultimately synthesize a molecule with optimal properties for the treatment of a target indication. Despite the development of computational methods for design, rationalization, and sometimes prediction of compound properties, this process is still largely empirical. Compounds are designed to test a hypothesis but then must be synthesized and isolated, so that progress is driven by the synthesis of physical material for testing.

Since the genomics boom of the 1990s, scientists have attempted to accelerate research with automation. In other industries, for example, in manufacturing environments, automation had been introduced with success in cases where largely identical tasks were carried out on largely identical objects. This approach could be applied in research both for repetitive tasks such as liquid handling and in largely analytical activities such as the preparation and analysis of biochemical assay plates. It was also applied with success in activities such as PCR where the same process was carried out repetitively on largely the same items (with there being only four monomers in DNA synthesis). Advances in molecular biology therefore significantly increased the capacity of target identification and in vitro screening, and as a result, particularly in early discovery, provision of molecules for testing became an ever more rate limiting step. The response to this was to move away from the iterative design-make-test cycle (where “test” encompassed parallel biochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological assays) that had previously proved profitable. The focus became the preparation of large compound collections based on historical concepts of “drug-likeness” which could be triaged against a target of interest.

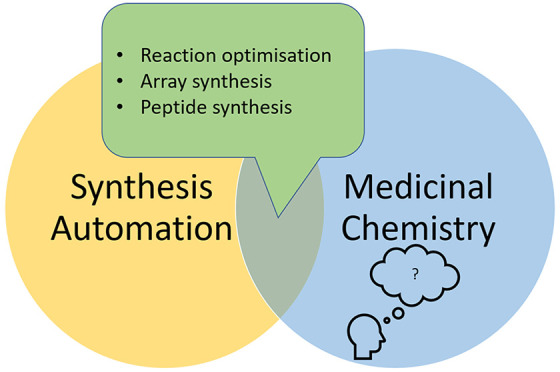

Early examples of successful automation in synthesis were also found in the solid phase synthesis of peptides: almost as soon as polystyrene supported peptide synthesis was invented by Merrifield1 in the 1960s, automated synthesizers were developed, and these have been optimized over the intervening years to provide efficient access to peptides. Peptide synthesis has undoubtably been a success story of automation. This can be connected to two important factors. First, synthesizing a peptide on a support, at least for smaller peptides, ensures most of the properties of the growing molecule are those of the solid support (Figure 1). The physical properties of the substrate are very predictable and consistent during both synthesis and downstream processes (such as washing to remove reagents). Second, development of robust “kit-ized” chemistries has meant that many molecules can reliably be synthesized with a few common standard protocols and reagent sets, which simplifies automation significantly.

Figure 1.

The properties of a substrate in solid supported synthesis are largely related to the polymer support due to the relative sizes.

As a result of this environment, for many years, the focus in synthetic chemistry was also on technologies which could assist efficiency by parallelization of related tasks and/or by synthesis on polymer solid support or novel alternatives such as DNA.2 Examples of applications for these technologies included chemistries robust enough for parallel synthesis of compound arrays in early hit to lead,3 high throughput reaction optimization,4,5 and the synthesis of large, closely related compound sets for hit generation6 and, in addition, auxiliary tasks such as reagent and monomer provision and the automated analysis and purification of the resulting, sometimes complex, reaction mixtures by high throughput HPLC.

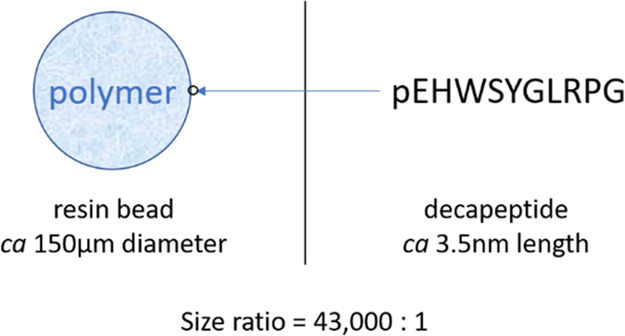

Automation has also been used to integrate key tasks such as synthesis, purification, and biochemical assay to attempt to reduce the design-make-test cycle time (Figure 2), either using parallel batch chemistry or iterative flow chemistry, in some cases with an in-line algorithm to design the next compound based on structure–activity relationships determined so far.7−12 Other researchers have integrated synthesis and analysis to aid optimization, in either batch or flow.13

Figure 2.

Design-make test cycle or “closed loop”.

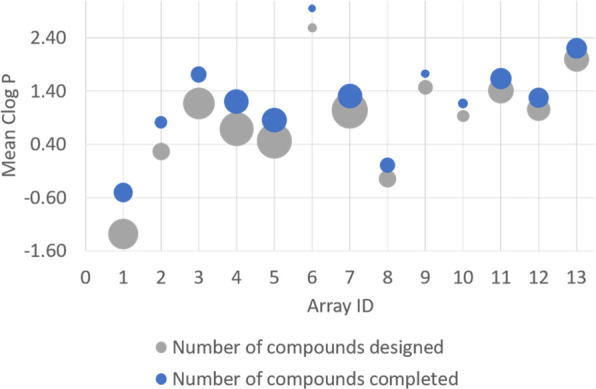

Although these innovations have succeeded in significantly improving the efficiency of some tasks, for example, the making of small targeted libraries for early stage hit and lead optimization, researchers have commented on the lack of structural diversity14,15 that can occur as a result of the use of the more kit-ized chemistries. Both groups, using different methods five years apart, identified a significant trend in the type of reactions being employed to access compounds in medicinal chemistry programs. A strong bias was observed toward reactions that can reliably be used in parallel chemistry such as amide bond formation and carbon–carbon bond formation by Suzuki–Mayura coupling. It was also noted that the final compounds formed were clustered in the area of chemical space defined as “linear” as opposed to “disc” and, particularly, “sphere”. In a previous analysis,16 automated synthesis methods and generic HPLC purification were identified as leading to a significant bias in compounds (Figure 3). It was found that these technologies were predisposed to select compounds toward the lipophilic end of drug-like properties, an area of chemistry space known to be nonoptimal for drug-likeness. It seems clear, as highlighted by these results, that efforts to improve productivity in synthesis have had the unintended consequence of self-selecting the compounds that are tested in drug discovery programs. The selection of synthesis technology is therefore critical to success in drug discovery programs and should be carefully considered.

Figure 3.

Coverage of initially targeted chemistry space is significantly reduced by synthesis and purification failures (data from Churcher et al.16).

As medicinal chemists attempt to explore new chemical space in order to drug more challenging targets, such as protein–protein interactions, previously useful chemistries and technologies will become less productive. To meet new challenges, it will be important to be able to efficiently explore structures inspired by natural products and endogenous ligands using the wide range of chemistries invented by previous generations of chemists as well as novel chemistries currently being invented.17 In fact, in many ways, chemists have been returning to the very productive iterative cycle of the 1970s and 1980s. This will require innovation in the state of the art in synthesis productivity tools to develop them beyond easily automatable chemistries. The aim of this review is therefore to explore innovation in this area, over the past five years, in novel synthetic methods and technologies developed to assist the synthetic chemist in hit exploration and lead optimization.

Review of Recent Publications in Synthesis Automation

Over the years, a large number of commercial systems have been developed, originally based on the requirements of parallel chemistry. Those that are still available for purchase today utilize automation to enable parallel processing of reactions. Systems include liquid handlers, parallel reaction blocks, solid dispensers, and parallel work up stations.18

Proprietary platforms have also been developed in industrial laboratories,19,20 and though often offering higher sophistication in automation and synthesis technologies (e.g., novel chemistries or flow chemistry systems), they still rely on batching of similar reactions. In some cases, researchers have also focused on integration of synthesis with other laboratory tasks such as analysis, purification, and screening to attempt to reduce cycle times.

In a recent example of direct integration of synthesis and screening, researchers at AbbVie21 chose to use parallel batch chemistry coupled via analysis and purification to plate base screening. Good correlation was observed between offline and online results. This platform builds on a body of work since 2006 to couple these activities either based on batch or flow chemistry. In this case, a mixture of proprietary and commercial instruments was integrated by using I/O lines to signal the readiness of each module for the next task.

Coupling of synthesis with analysis is also a continuing theme. New approaches include the use of nanoscale dispensing and UPLC-MS, sampling of reactions from a 384-well plate, and spotting for DESI-MS analysis or use of droplets generated by electrospray ionization and mass spectrometry to analyze reaction outcomes.22,23 These systems are focused on parallel exploration of reaction space, assessing a very large number of reaction parameters while using minimal reactant quantities. The aim is to identify profitable areas for further optimization rather than to develop conditions which can be used immediately, on a larger scale, in a conventional reaction vessel.

Sach and co-workers24 have used dispersion in a plug flow system to create concentration gradients for the optimization of Suzuki–Mayura reactions of two substrates, testing combinations of solvents, ligands, and reactants with 0.4 μm of substrate used for each reaction. Up to 1500 reactions could be analyzed in 24 h with online UPLC-MS. The benefit of this flow approach is that conditions identified can be easily scaled by use of multiple reaction plugs in the same system which should guarantee the same outcome despite the increase in scale.

Further recent developments have focused on the use of cloud computing resources, artificial intelligence, and incorporation of flow chemistry in attempts to increase the usefulness of traditional parallel chemistry batch systems. A recently launched example is the latest iteration of the Eli Lilly early discovery automation project: the Lilly Life Sciences Studio Lab, developed as a collaboration with Strateos Inc. and including their Robotic Cloud Lab platform. The lab promises closed loop discovery (Figure 2) with synthesis and screening automation accessible remotely through a cloud-based interface. The synthesis platforms incorporated are limited to conventional commercially available parallel chemistry systems which can be used to carry out a number of standard reaction chemistries.25 Another Web site promising web-based access to chemistry is Deepmatter, who have recently announced a collaboration with Astra Zeneca.26 The Web interface is currently limited to very simple test chemistries with basic parameters monitored by prototype devices akin to data loggers.

A large investment in synthesis technology itself has come from the US DARPA Make-it program which has funded several projects. Not-for-profit research institute SRI International27 has recently released details of one of these research programs, the $30 million Synfini project. Full details have not yet been published; however, the platform comprises an artificial-intelligence-based synthesis planning software tool, an ink-jet-printer-based nanoscale reaction optimization platform, and a reconfigurable flow chemistry-based synthesis platform. The synthesis planning tool combines a fast reaction database search with a reaction generator, which uses random forest and multilayer perceptron generated reaction classifiers to predict reactions. These reaction suggestions are then tested using design of experiments and parallel experimentation in order to triage and optimize routes to a target suggested by the software. Unlike the previously mentioned Merck and Purdue systems,22,23 in this case, the droplets are generated using thermal ink jet printer technology rather than electrospray. The researchers suggest that the system can screen and optimize parameters such as time, temperature, stoichiometry, pH, reagents, solvents, and substrates in two to four step reactions in an automated fashion. The final part of the system is a flow chemistry scale up platform with integrated LC-MS and 1H NMR analysis to generate material for testing based on the conditions identified from droplet chemistry. The system also has detailed capture of conditions and data to aid reproducibility and transferability and which will also be used to continuously improve future synthetic route planning and synthetic process optimization.

Another DARPA Make it funded program, at MIT, also focused on exploiting flow chemistry in the development of a modular system centered around a six-axis robot. The robot picks fluidic modules for syntheses (defined by a synthesis planning software) from a stack and places them on a “switchboard” to form fluidic pathways for up to eight linear steps or five convergent steps. The system was tested by using the synthesis of several active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).28 The synthesis planning software is based on rules extracted algorithmically from reaction databases which are then applied to synthesis problems using a feed-forward neural net to decide which rules are most applicable to the target molecule. A binary classifier is then used to decide whether a disconnection is plausible; then, the reaction is evaluated by a forward prediction model. Uniquely, the synthesis planner is able to plan chiral syntheses, as rules for synthesis involving chiral molecules were also extracted from the database. This system is also able to suggest reactants, although the researchers note that, due to the mainly batch chemistry data sets available, these often must be adjusted by the human chemist to be compatible with flow chemistry.

Both of these systems have focused on flow chemistry for scale up of successful reaction conditions. This is partly to exploit the inherent scalability of flow chemistry where, once successful conditions are identified, the system can be run for longer to generate more material. Additionally, flow chemistry is used to enable automation, as it has been relatively easy to automate based on valves and pumps developed for other applications such as HPLC. The ability to dissolve one’s starting materials and reagents at the concentrations required in the solvent demanded by the reaction is a key limit to this technology, but in the cases where this challenge has been met, the reduction to automation practice becomes a relatively straightforward one of liquid handling and pumping. Significant advantages can be seen from better control of mixing and heating and the ability to carry out online monitoring and to concatenate reactions together where conditions are compatible.

In the case where flow chemistry is not the best format, batch and flow have been combined together using a flow chemistry platform as the base, with modified glassware to carry out batch reactions.29 The system also includes integrated liquid–liquid extraction using optical detection of a marker at the interface and solvent exchange via evaporation and redissolution. The system can be monitored remotely via a web interface. Another approach to a highly integrated system for accessing API was also explored using batch chemistry methodology and precedented methods from the literature.30 In this case, standard laboratory batch apparatus, such as round-bottom flasks, separating funnels, and filtration glassware rotary evaporators, were integrated with fluidics to enable automated multistep synthesis controlled by a computer. The researchers also point out the benefits of digitalization in reproducibility of methods and data capture.

Another recent trend has been to revisit the benefits of “kit-ised” solid supported peptide and oligo synthesis. One example of this has been the development over the past few years of MIDA boronate reagents for iterative cross coupling chemistry and their incorporation in an automated system using silica columns to immobilize the chemistry.31 The researchers reported that a large range of compounds, from polyketide natural products to heterocyclic small molecules, could be accessed through the application of iterative MIDA boronate couplings. The properties of the MIDA boronate moiety were used to allow catch and release purification on silica, facilitating automated synthesis on the bespoke platform. It was noted that there are limitations to the general applicability of the technology as aqueous base or strongly basic reaction conditions lead to decomposition of the boronate.

A further example of kit chemistry is the cartridge-based system developed by Synple32 for which reagent kits can be purchased in cartridge format for common reactions. The reaction occurs in a vial, and the work up is accomplished automatically by the system using solid supported scavengers. The cartridges are limited in scope at present, focusing on heterocycle formation, Mitsunobu reaction, reductive amination, and reactions of interest in chemical biology such as protac and biotinylation.

As previously mentioned, a key area of recent publication has been synthesis planning software. For decades, research has been ongoing into the automation of chemical route design, mostly focused on the manual codifying of chemical literature into heuristic rules for retro- and forward synthesis planning. One of these programs (Chematica33), developed by GSI International (also Make-it funded), has been commercialized by Merck Sigma-Aldrich as Synthia and is now available to license through a web interface. This software was the result of a 10-year program using chemists to extract rules manually from the scientific literature, as initial attempts to do this automatically were unsuccessful. More recent efforts have been able to use advances in computing power and neural networks to speed up this process. As previously mentioned, Jensen and co-workers28 were able to algorithmically extract rules from a reaction database. As part of their modular flow synthesis platform, the synthesis planning tool is also able to suggest routes including reagents from the (mostly) batch literature which were manually modified for the flow platform.

Also recently published, the approach of Segler et al. uses Monte Carlo tree search and neural networks to design routes which were assessed by human chemists in a double-blind test against routes selected from the literature by expert human chemists.34 The researchers found no significant preference for the literature routes over the algorithmically generated routes. A second piece of research published previously by the same group35 is also notable in that it does not use a rules-based approach. This work, similarly, using neural networks, uses a process of identifying analogous or complementary reactivity of two molecules based on their known behavior and then predicting the likely reaction by inductive inference. The method does not rely on extracted rules or expert systems and considers molecules as a whole rather than their functional groups. The system was able to predict the products of a set of previously unseen test reactions with an accuracy of 67.5%, which compared well with a rules-based system. The authors also looked at the system’s ability to predict novel reaction types and reactants for novel reactions not occurring in the test set. It was able to predict the outcomes of these novel reactions correctly in an impressive 35% of cases as well as predict reactants considered to be reasonable by human assessors. Although this work is in its early stages, it holds out the interesting possibility of an algorithm possessing chemical intuition which could be able to usefully invent new reactions.

Discussion: Impact of Recent Advances

Synthesis automation has always held out the promise of greater productivity and improved reproducibility, an issue ever more relevant as lack of reproducibility in the scientific literature is increasingly highlighted as a waste of resources in both the originator groups and those that attempt to repeat or build on the research.36 However, the implementation has fallen short of the promise.

In the 1990s, many automation investments resulted in expensive platforms, installed in proprietary laboratories which stood idle for long periods. These systems ultimately found limited use due to lack of flexibility and reliability, high cost of capital, and requirement for specialist operators limiting usefulness for synthetic chemists. The requirement for flexibility has been a key issue: in other industries where automation has been used, repetitive tasks are identified for automation; i.e., the same procedure is carried out on the same item. In synthesis (and other research tasks), this approach has been successful in some activities, for example, in the automation of analytical experiments such as LC-MS and NMR, where largely the same protocol is applied to largely the same object (a sample in a vial or tube). It is worth noting that in these cases the experiment can easily be repeated if an error or an unforeseen event occurs. In synthesis, this approach is only appropriate (and can be very useful) where robust chemistries can be performed on similar substrates where losses due to unforeseen events can be tolerated. Systems of this type tend to be used in specific activities such as targeted array preparation and reaction optimization. For activities not meeting these criteria, these systems rarely offered any advantage.

Over the last five years there has been huge investment from public bodies such as DARPA in the US and the EPSRC in the UK, as well as continuing funding by pharmaceutical companies and private instrument developers. As such, the question arises as to how much the current state of the art has moved on from similar systems developed a quarter of a century ago such as the Myriad Core System or the Zymark Twister?

One observation is that the increased availability of cheap processing power has had an impact. An example of this is the Strateos platform. Accessibility on a subscriber basis via a cloud-based web platform may assist with barriers associated with high capital investment and the requirement for specialist automation knowledge in the user through service-based access to capital equipment and specialist operators. Carrying out synthetic chemistry within automated systems for increased data capture regarding methods and outcomes has also been a theme. Although in its early stages, this could be a key solution to improving reproducibility and repeatability of synthesis. In addition, advances in computer power appear to be increasing the usefulness of synthesis planning tools which now seem to be offering a realistic prospect of automated idea generation for route planning and even the generation of novel chemical step ideas. Although AI will undoubtably assist with the task of generating ideas for synthesis, in many ways, this does not currently constitute a bottleneck. The testing of synthesis ideas with practical experimentation is still essential but slow and rate limiting.

Review of the literature relating to physical automation of synthesis over the last five years reveals the persistence of two themes from the era of combinatorial chemistry: complex automation platforms, integrating some of the activities of the medicinal chemistry laboratory, and simplification of chemistry to better suit the capabilities of the automation, echoing the same principles explored in the previous three decades of research. This approach was founded in the strategy of selecting targets for synthesis which are amenable to parallel chemistry and automation. This has undoubtably had a large impact on the nature of the compounds being made and tested in drug discovery programs with the increasing reliance on easy to parallelize reactions such as amide bond formations, Suzuki–Mayura couplings, and the impact seen on the properties of final compounds.

A key question in medicinal chemistry is whether it is sufficient to address the easily accessible chemistry space defined by these chemistries or whether there is in fact a need, particularly when considering novel targets, to use a wider range of chemistries to access “more difficult” compounds. If the latter is the case, then there is a strong need to have the productivity tool fit the chemistry and the chemist rather than the other way round.

The majority of the work published over the last five year focuses on supporting parallel experimentation, synthesis of a specific compound where the experimental parameters are known in advance to a large degree, or methods of developing the chemistry to fit the equipment. Chemistry synthesis is a highly skilled creative science based on a solid understanding of theory and an ability to analyze the state of the art in an area and extrapolate to develop conditions for the synthesis of entirely novel compounds. However, a large part of a chemist’s day is taken up with repetitive activities which nevertheless require high levels of manual dexterity and experience, attributes which until recently were almost the exclusive domain of the human researcher. In reviewing recent progress, there has been limited work which is likely to result in meaningful improvements in this area. When considering automation that has been almost seamlessly adopted into every laboratory, one notes the following features:

-

1.

Flexibility with respect to compounds and chemistry

-

2.

Low levels of automation

-

3.

Modularity

-

4.

Walk up use

-

5.

Ability to add value over the manual equivalent

-

6.

Compatibility with iterative hypothesis generation and test

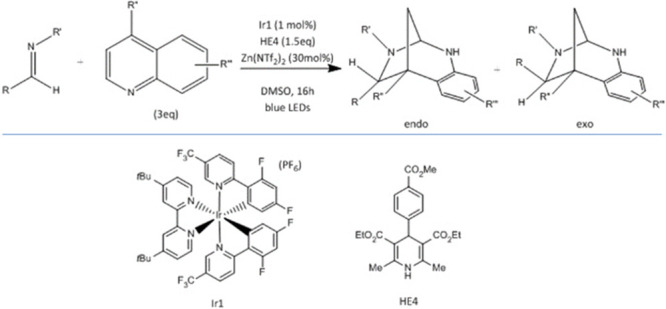

Examples that have fitted these criteria over the past 30 years include automated shim and sample loading for NMR, automated vacuum pump rotary evaporators, hot plate stirrers with integrated temperature probes, generic automated LC-MS, automated microwave reactors, and automated flash chromatography systems. There are very few examples of novel synthesis technologies that have been added to this list in the past decade. A possible reason for this is the focus by researchers on the development of fully integrated, highly engineered systems which, although suitable for small array generation with standard chemistries, are expensive, complex, and not flexible enough for the more iterative process of lead optimization. For this task, a more modular approach can put useful and cost-effective tools into the hands of the synthetic chemist. An example of this, widely used in our laboratories, are standalone flow reactors. These systems are simple to use with low levels of automation but are supported by software which enables a nonexpert user to achieve successful results, for example, the Flow Commander software produce by Vaportec37 which models the flow of a plug through the system. Modular additions to these platforms can allow the use of technologies such as electrochemistry38 and photochemistry39,40 which in the past had high barriers to use due to the lack of easy-to-use equipment. Another recent development in this area is the PhotoRedox Box from Hepatochem41 which allows parallel batch optimization of photochemical reactions. Preprepared kits of photocatalysts, bases, and solvents have been designed to allow use by the nonexpert. Photochemistry is now being used more widely to enable the production of novel and complex chemotypes as exemplified by a recent paper42 showing the screening of a wide range of photocatalysts, bases, and solvents to find conditions for the synthesis of bridged 1,3-diazepanes (Scheme 1). Lowering these barriers will certainly be beneficial for chemists wishing to access alternative chemistry space.

Scheme 1. Dearomative Synthesis of Bridged 1,3-Diazepanes Using Photochemistry.

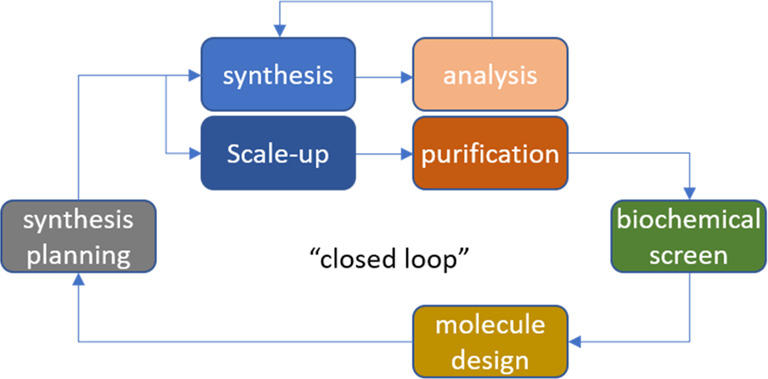

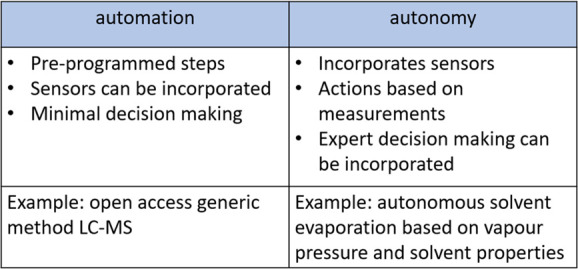

Despite the availability of these reactors, techniques such as photochemistry and electrochemistry still require significant specialist knowledge to be successfully used. As artificial intelligence is starting to make an impact in synthesis planning, the focus of productivity tools can switch from automation to autonomy. In our laboratory, we define automation as a process performed without human assistance, while autonomy is satisfactory performance under uncertainties in the environment and the ability to compensate for system failures without external intervention. In addition, a key goal for us is to develop tools that provide advantages over manual techniques.

The ultimate promise of this area of research is the potential for autonomous discovery platforms, and the progress and challenges here have been set out clearly by reviewers including Jensen et al.43,44 One challenge identified was expanding the scope of automatable experiments where “design space ... is limited by the capabilities of the automated hardware available”. There seems to be ample opportunity for algorithms and machine learning to also enhance productivity tools for synthesis, such as assisting chemists in autonomously identifying suitable conditions such as wavelength, catalyst, electrode material, voltage, and solvent or in reacting to unforeseen situations as they happen.

Liquid–liquid extraction is a key technique for cleanup of reactions. Although quick and straightforward in an ideal case, the method is more usually slow and challenging when processing real life samples where particulates may cause emulsions to form or reaction solvent with solubility in both organic and aqueous phase complicates separations. Over the years, several approaches to automating this process have been developed, including conductivity measurements,45 membrane separation in flow46 or batch,47 and optical methods.48 In our hands, conductivity has been the most reliable and flexible for real reaction mixtures. However, regardless of the approach, experience is required to select the best solvents and washes and to modify the technique, as complicating factors such as emulsion formation are encountered.

Use of a microfluidic conductivity cell for liquid–liquid extraction fits our criteria for autonomy (Figure 4) and superiority over the manual process. Emulsions are broken on passing through the cell due to the cell potential difference affecting the zeta potential.49 The addition of algorithms to determine the interface in realistic situations (e.g., where a polar solvent such as dimethylformamide is partly dissolved in the aqueous layer) and machine learning to select the appropriate algorithm based on the properties of the solution make this device flexible, simple to use, and superior to the traditional manual alternative.

Figure 4.

Features of automation vs autonomy.

In order to improve levels of autonomy in laboratory tools, a key challenge is to enable machines to recognize laboratory apparatus in the same abstract way as a human chemist who can recognize a vessel as such regardless of whether it is a vial, a round-bottom flask, or a conical flask. A recent publication50 focuses on this challenge. A convolutional neural net was trained to recognize laboratory equipment such as separating funnels, beakers, and conical flasks as well as identify the physical form of the contents. A tool based on this system could potentially be used to autonomously identify a worked-up organic phase and add and filter off drying agent in a much more robust way than a preconfigured, fixed architecture robotic system.

In addition, there are aspects of the highly integrated systems reviewed here-in which, if packaged into modules and given a degree of autonomy, may meet the criteria for flexibility and advantage over manual processes. An example of this was an integrated synthesis and test platform using flow chemistry coupled via HPLC purification and quantification to a plate-based bioassay with an integrated search algorithm to select the next compound for synthesis based on the biochemical data.8 The overlap of the chemistry space accessible and the assays which could be integrated limits the usefulness of the integrated platform. However, the ability to inject crude reaction mixture into an assay via purification and quantification is a very useful standalone unit for a medicinal chemistry laboratory.

Conclusions

If one walks into the average medicinal chemistry lab, one will see chemists using round-bottom flasks, not a high-tech, automated, Amazon-style research factory. What a medicinal chemist truly requires are synthesis efficiency tools that assist in cases where chemistries, reactors, and methods need to be flexible and easy to use, and there is a limited progress in this area.

The contribution of the synthetic chemist requires persistence, imagination, experience, practical dexterity, and theoretical knowledge. As exemplified in our lab, chemists drive to find conditions to make complex compounds that will test a hypothesis, where there is no precedent in the literature and trying many conditions and reactor formats. In many cases, a very specific structure is needed to test the hypothesis, and these compounds are often the outliers which become valuable products. Something that is similar by some measure and easier to make is not always good enough. In our small commercial lab, as in many others, we must take a pragmatic approach to capital equipment, software, and technology and it is instructive to observe the tools which are favored by our chemists. These tend to be modular equipment with limited “AI” and automatic feedback loops. Our chemists are by no means technology-phobes, being specialists in flow and machine assisted chemistry, but our goal of accessing exactly the best molecules for our research collaborations and internal discovery projects drives the use of only the tools which help this goal, characterized by increased autonomy rather than high levels of automation.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge colleagues at New Path Molecular, Prof S. V. Ley and Dr Nikzad Nikbin, for inspirational discussions on synthesis automation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DARPA

Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EPSRC

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council

- HPLC

high pressure liquid chromatography

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

The liquid–liquid extraction project was partly funded by AbbVie Inc.

The author declares the following competing financial interest(s): Elizabeth Farrant is an employee and shareholder of New Path Molecular Research.

References

- Merrifield R. B. Solid phase peptide synthesis. I. The synthesis of a tetrapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85 (14), 2149–2154. 10.1021/ja00897a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ottl J.; Leder L.; Schaefer J. V.; Dumelin C. E. Encoded library technologies as integrated lead finding platforms for drug discovery. Molecules 2019, 24 (8), 1629. 10.3390/molecules24081629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppitz M.; Eis K. Automated medicinal chemistry. Drug Discovery Today 2006, 11 (11–12), 561–568. 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell A. I.High Throughput Reaction Screening. In New Synthetic Technologies in Medicinal Chemistry; Farrant E., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, 2011; pp 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Krska S. W.; DiRocco D. A.; Dreher S. D.; Shevlin M. The evolution of chemical high-throughput experimentation to address challenging problems in pharmaceutical synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50 (12), 2976–2985. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannocci L.; Leimbacher M.; Wichert M.; Scheuermann J.; Neri D. 20 years of DNA-encoded chemical libraries. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (48), 12747–12753. 10.1039/c1cc15634a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Suarez M.; Garcia-Egido E.; Montembault M.; Chapela M. J.; Wong-Hawkes S. Y.. The Development of Integrated Microfluidic Chemistry Platforms for Lead Optimisation in the Pharmaceutical Industry. In ASME 4th International Conference on Nanochannels, Microchannels, and Minichannels 47608; 2006; 997–1002.

- Desai B.; Dixon K.; Farrant E.; Feng Q.; Gibson K. R.; van Hoorn W. P.; Mills J.; Morgan T.; Parry D. M.; Ramjee M. K.; Selway C. N. Rapid discovery of a novel series of Abl kinase inhibitors by application of an integrated microfluidic synthesis and screening platform. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56 (7), 3033–3047. 10.1021/jm400099d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.; Lamb M. L.; Zhang T.; Hennessy E. J.; Grewal G.; Sha L.; Zambrowski M.; Block M. H.; Dowling J. E.; Su N.; Wu J. Discovery of potent KIFC1 inhibitors using a method of integrated high-throughput synthesis and screening. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (23), 9958–9970. 10.1021/jm501179r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechtizky W.; Dedio J.; Desai B.; Dixon K.; Farrant E.; Feng Q.; Morgan T.; Parry D. M.; Ramjee M. K.; Selway C. N.; Schmidt T.; Tarver G. J.; Wright A. G. Integrated Synthesis and Testing of Substituted Xanthine Based DPP4 Inhibitors: Application to Drug Discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 768–772. 10.1021/ml400171b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M.; Kuratli C.; Martin R. E.; Hochstrasser R.; Wechsler D.; Enderle T.; Alanine A. I.; Vogel H. Seamless integration of dose-response screening and flow chemistry: efficient generation of structure-activity relationship data of beta-secretase (BACE1) inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1704–1708. 10.1002/anie.201309301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guetzoyan L.; Ingham R. J.; Nikbin N.; Rossignol J.; Wolling M.; Baumert M.; Burgess-Brown N. A.; Strain-Damerell C. M.; Shrestha L.; Brennan P. E.; Fedorov O.; Knapp S.; Ley S. V. Machine-assisted synthesis of modulators of the histone reader BRD9 using flow methods of chemistry and frontal affinity chromatography. MedChemComm 2014, 5 (4), 540–546. 10.1039/C4MD00007B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houben C.; Lapkin A. A. Automatic discovery and optimization of chemical processes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2015, 9, 1–7. 10.1016/j.coche.2015.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley S. D.; Jordan A. M. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (10), 3451–3479. 10.1021/jm200187y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G.; Bostrom J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone?. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadin A.; Hattotuwagama C.; Churcher I. Lead-oriented synthesis: a new opportunity for synthetic chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51 (5), 1114–1122. 10.1002/anie.201105840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos K. R.; Coleman P. J.; Alvarez J. C.; Dreher S. D.; Garbaccio R. M.; Terrett N. K.; Tillyer R. D.; Truppo M. D.; Parmee E. R. The importance of synthetic chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry. Science 2019, 363 (6424), eaat0805. 10.1126/science.aat0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples, see: unchainedlabs.com, zinsserna.com, chemspeed.com, amigochem.com.

- Godfrey A. G.; Masquelin T.; Hemmerle H. A remote-controlled adaptive medchem lab: an innovative approach to enable drug discovery in the 21st Century. Drug Discovery Today 2013, 18 (17–18), 795–802. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu N. P.; Sarris K.; Searle P. A. An Automated Microwave Assisted Synthesis-Purification System for Rapid Generation of Compound Libraries. J. Lab. Aut. 2016, 21, 459–469. 10.1177/2211068215590580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranczak A.; Tu N. P.; Marjanovic J.; Searle P. A.; Vasudevan A.; Djuric S. W. Integrated platform for expedited synthesis–purification–testing of small molecule libraries. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8 (4), 461–465. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago Santanilla A.; Regalado E. L.; Pereira T.; Shevlin M.; Bateman K.; Campeau L.-C.; Schneeweis J.; Berritt S.; Shi Z.-C.; Nantermet P.; Liu Y.; Helmy R.; Welch C. J.; Vachal P.; Davies I. W.; Cernak T.; Dreher S. D. Nanomole-scale high-throughput chemistry for the synthesis of complex molecules. Science 2015, 347 (6217), 49–53. 10.1126/science.1259203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wleklinski M.; Falcone C. E.; Loren B. P.; Jaman Z.; Iyer K.; Ewan H. S.; Hyun S. H.; Thompson D. H.; Cooks R. G. Can accelerated reactions in droplets guide chemistry at scale?. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016 (33), 5480–5484. 10.1002/ejoc.201601270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perera D.; Tucker J. W.; Brahmbhatt S.; Helal C. J.; Chong A.; Farrell W.; Richardson P.; Sach N. W. A platform for automated nanomole-scale reaction screening and micromole-scale synthesis in flow. Science 2018, 359 (6374), 429–434. 10.1126/science.aap9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou C. A.; Humblet C.; Hu H.; Martin E. M.; Dorsey F. C.; Castle T. M.; Burton K. I.; Hu H.; Hendle J.; Hickey M. J.; Duerksen J. Idea2Data: toward a new paradigm for drug discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (3), 278–286. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepmatter.com. Collaboration with Astra Zeneca. https://www.deepmattergroup.com/content/press/archive/2019/091219 (accessed June 26, 2020).

- SRI.com. Synfini. An automated synthetic chemistry platform. https://www.sri.com/case-studies/synfini/ (accessed June 26, 2020).

- Bédard A. C.; Adamo A.; Aroh K. C.; Russell M. G.; Bedermann A. A.; Torosian J.; Yue B.; Jensen K. F.; Jamison T. F. Reconfigurable system for automated optimization of diverse chemical reactions. Science 2018, 361 (6408), 1220–1225. 10.1126/science.aat0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D. E.; Ley S. V. Reaction chemistry & engineering reactions on a single, automated reactor. React. Chem. Eng. 2016, 1, 629–635. 10.1039/C6RE00160B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner S.; Wolf J.; Glatzel S.; Andreou A.; Granda J. M.; Keenan G.; Hinkley T.; Aragon-Camarasa G.; Kitson P. J.; Angelone D.; Cronin L. Organic synthesis in a modular robotic system driven by a chemical programming language. Science 2019, 363 (6423), eaav2211. 10.1126/science.aav2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Grillo A. S.; Burke M. D. From synthesis to function via iterative assembly of N-methyliminodiacetic acid boronate building blocks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (8), 2297–2307. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T.; Bordi S.; McMillan A. E.; Chen K.-Y.; Saito F.; Nichols P.; Wanner B.; Bode J. W.. An Integrated Console for Capsule- Based, Fully Automated Organic Synthesis; 2019. DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv.7882799.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klucznik T.; Mikulak-Klucznik B.; McCormack M. P.; Lima H.; Szymkuć S.; Bhowmick M.; Molga K.; Zhou Y.; Rickershauser L.; Gajewska E. P.; Toutchkine A. Efficient syntheses of diverse, medicinally relevant targets planned by computer and executed in the laboratory. Chem. 2018, 4 (3), 522–532. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segler M. H.; Preuss M.; Waller M. P. Planning chemical syntheses with deep neural networks and symbolic AI. Nature 2018, 555 (7698), 604–610. 10.1038/nature25978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segler M. H.; Waller M. P. Modelling chemical reasoning to predict and invent reactions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (25), 6118–6128. 10.1002/chem.201604556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. Reproducibility crisis?. Nature 2016, 533 (26), 353–66.27193681 [Google Scholar]

- Vapourtec Ltd, UK. www.vapourtec.com.

- Yan M.; Kawamata Y.; Baran P. S. Synthetic organic electrochemistry: calling all engineers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (16), 4149–4155. 10.1002/anie.201707584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; May O.; Blakemore D. C.; Ley S. V. A Photoredox Coupling Reaction of Benzylboronic Esters and Carbonyl Compounds in Batch and Flow. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (15), 6140–6144. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Filippo M.; Bracken C.; Baumann M. Continuous Flow Photochemistry for the Preparation of Bioactive Molecules. Molecules 2020, 25 (2), 356. 10.3390/molecules25020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatochem Inc, USA. www.hepatochem.com.

- Leitch J. A.; Rogova T.; Duarte F.; Dixon D. J.. Diverting the Minisci Reaction: Dearomative Photocatalytic Construction of Bridged 1,3-Diazepanes; 2019. 10.26434/chemrxiv.10284104.v1. Downloaded July 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Coley C. W.; Eyke N. S.; Jensen K. F. Autonomous discovery in the chemical sciences Part I: Progress. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2–38. 10.1002/anie.201909987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley C. W.; Eyke N. S.; Jensen K. F. Autonomous discovery in the chemical sciences Part II: Outlook. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2–25. 10.1002/anie.201909989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S.; Moshiri B.; Durand R. Automation of Liquid-liquid extraction using phase boundary detection. JALA 2002, 7 (1), 74–77. 10.1016/S1535-5535-04-00178-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FLLEX module from Syrris Ltd. , UK and Zaiput Flow Technologies, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Biotage AB, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham R. J.; Battilocchio C.; Fitzpatrick D. E.; Sliwinski E.; Hawkins J. M.; Ley S. V. A systems approach towards an intelligent and self-controlling platform for integrated continuous reaction sequences. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (1), 144–148. 10.1002/anie.201409356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUPAC . Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the “Gold Book”). Compiled by McNaught A. D., Wilkinson A.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, U.K., 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eppel S.; Xu H., Bismuth M.; Aspuru-Guzik A.. Computer vision for recognition of materials and vessels in chemistry lab settings and the Vector-LabPics dataset. Preprint. 2020. 10.26434/chemrxiv.11930004.v2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]