Abstract

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) is thought to play a pathogenic role in chronic immune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. While covalent, irreversible Btk inhibitors are approved for treatment of hematologic malignancies, they are not approved for autoimmune indications. In efforts to develop additional series of reversible Btk inhibitors for chronic immune diseases, we sought to differentiate from our clinical stage inhibitor fenebrutinib using cyclopropyl amide isosteres of the 2-aminopyridyl group to occupy the flat, lipophilic H2 pocket. While drug-like properties were retained—and in some cases improved—a safety liability in the form of hERG inhibition was observed. When a fluorocyclopropyl amide was incorporated, Btk and off-target activity was found to be stereodependent and a lead compound was identified in the form of the (R,R)- stereoisomer.

Keywords: Kinase inhibitor, Btk, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiomyocytes, hERG

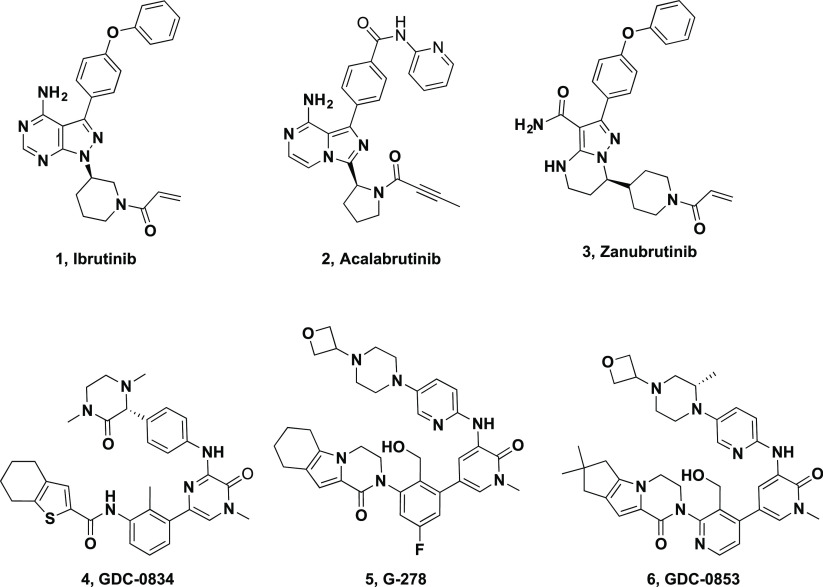

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that is expressed in all hematopoietic cells except T cells.1,2 Antigen binding to the B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) on B lymphocytes and immune complex binding to Fc receptors (e.g., FcγR, FcεR) on myeloid cells activate Btk.1,3−5 Preclinical and emerging clinical data support the hypothesis that inhibition of Btk may be effective for the treatment of immunological disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), diseases in which B cells and/or myeloid cells foster an excessive autoimmune response.4−17 Thus, significant efforts have been expended over the past two decades toward the goal of developing Btk inhibitors for treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases and hematologic malignancies.18 Irreversible Btk inhibitors ibrutinib 1 (PCI-32765, Imbruvica),19 acalabrutinib 2 (ACP-196, Calquence),20,21 and zanubrutinib 3 (BGB-3111)22 are approved for treatment of B-cell malignancies (Figure 1). Given the potential concern with the chronic use of covalent inhibitors, our efforts focused on noncovalent inhibitors to achieve a clinical profile appropriate for the treatment of immune diseases.

Figure 1.

Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, and Genentech’s published Btk inhibitors.

We previously reported the discovery and structure–activity relationship (SAR) of several series of noncovalent Btk inhibitors. In those efforts we optimized beyond our first clinical inhibitor, GDC-0834 (4),23,24 to molecules such as G-278 (5) by incorporating tricyclic ring systems.25 However, 5 and analogs had low safety margins in rat and dog,26 in line with a cytotoxicity observed in primary human hepatocytes.27 Subsequent efforts focused on modifying the partially solvent-exposed aryl piperazine and lowering both the logD and the predicted human dose.27,28 These efforts led to the identification of the highly potent and selective, noncovalent Btk inhibitor fenebrutinib (GDC-0853, 6), currently in late-stage clinical development for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

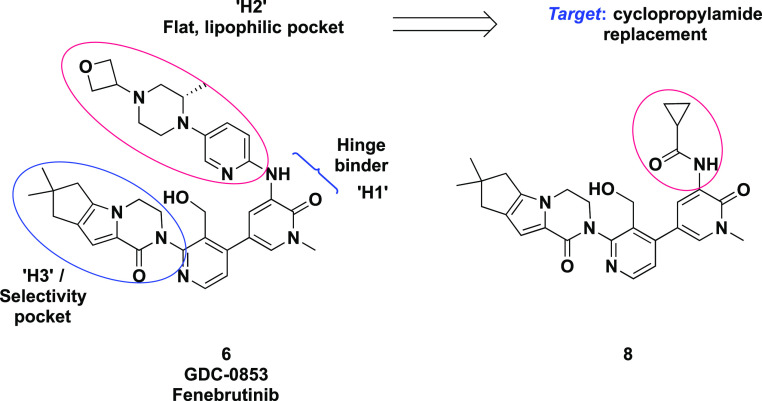

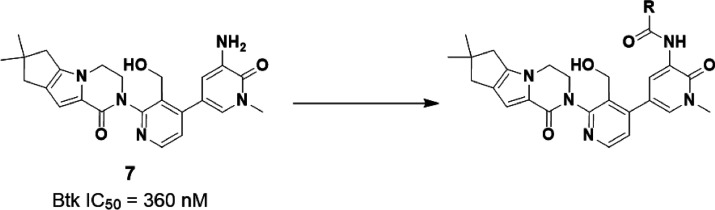

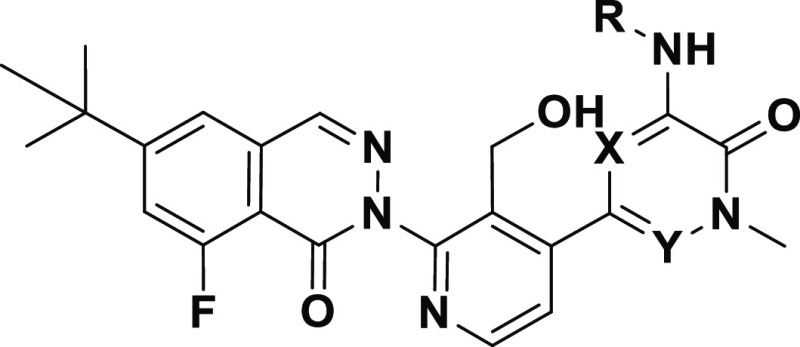

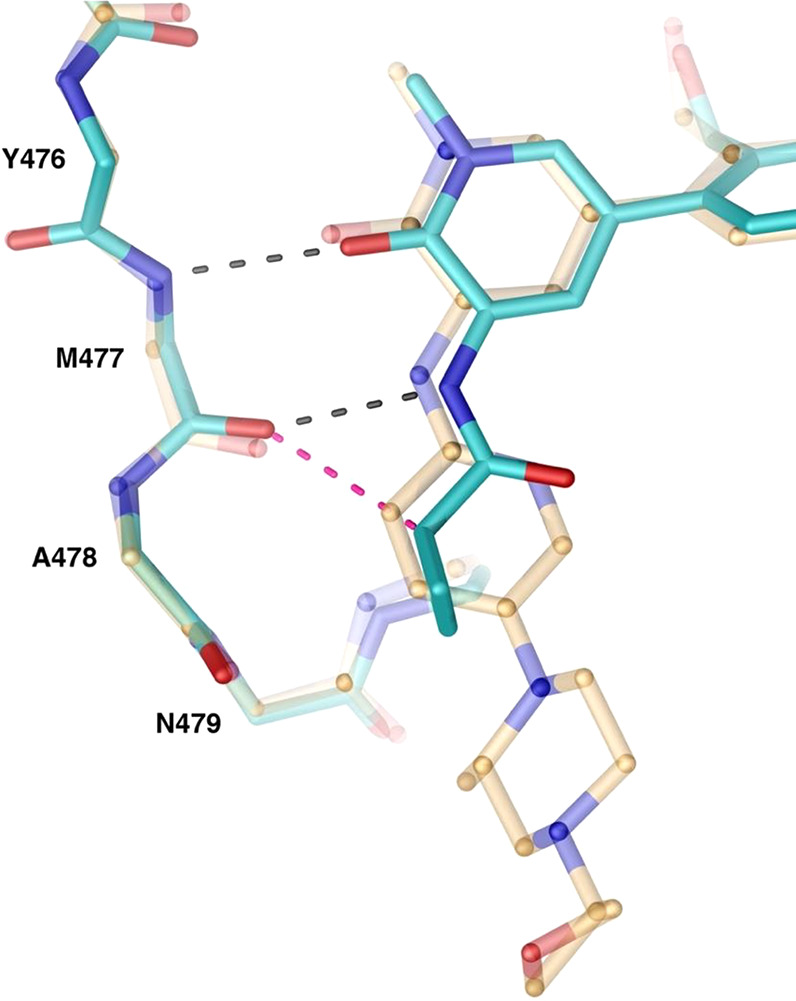

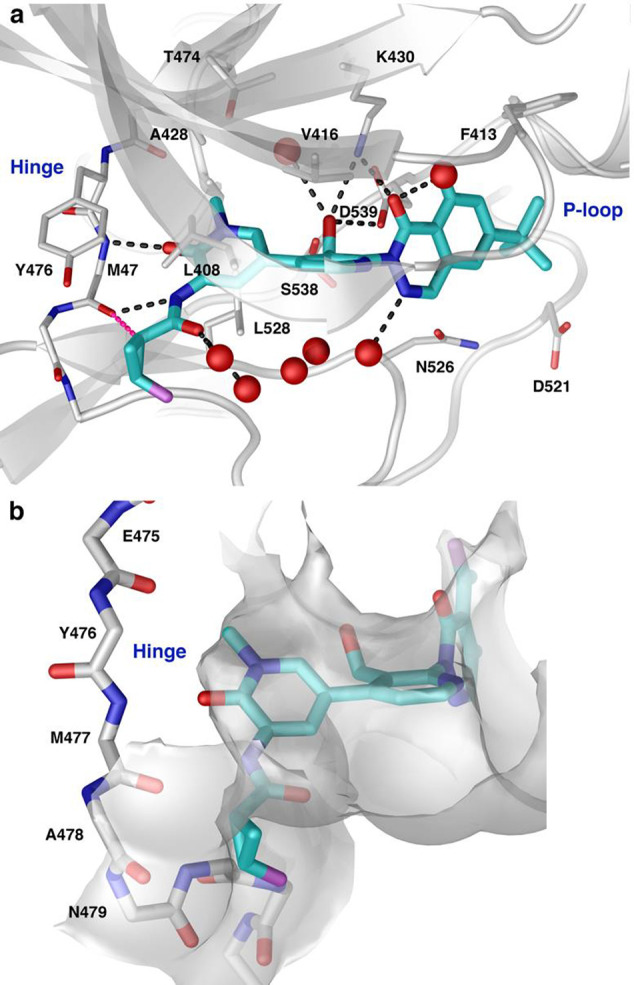

In parallel, we set out to identify additional series with structural diversity from 6, a strategy that might also avoid potential bioactivation of the 1,4-disubstituted aromatic ring that has been implicated in many toxicities including drug induced liver injury.28,29 Since the H3 tricyclic motif and the hydroxymethyl pyridyl ring linker were extensively optimized, we explored the partly solvent-exposed H2 region of the molecule. We hypothesized that replacing the aromatic ring with a suitably substituted amide might offer a viable starting point.30 In particular, we hoped that a small cyclopropane carboxamide might replicate the sp2 character of the pyridyl π system (Figure 2); others have reported such substitutions in different kinases.31,32 Molecular modeling of cyclopropane carboxamide 8 in Btk (Figure 3) suggested that the carbonyl oxygen overlaps with the pyridine nitrogen of 6, orienting the amine N–H toward the hinge. We hypothesized that by removing an aromatic ring, amide analogues would benefit from lower molecular weight and lipophilicity, lack of a basic amine, and improved aqueous solubility.33,34

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the hinge binding (H1), lipophilic pocket (H2), and selectivity pocket (H3) elements of Btk inhibitor fenebrutinib (6, GDC-0853), and the disconnection of the proposed isosteric cyclopropylamide in the H2 pocket with 8.

Figure 3.

Model of a cyclopropane carboxamide as an isostere for 2-aminopyridine. Superposing computationally docked 8 (cyan) on the Btk crystal structure with 6 (tan) indicates that replacing the pyridine tail of 6 with cyclopropylamide retains pyridone hydrogen bonding with the hinge and forms an additional interaction with the polarized cyclopropyl C–H.

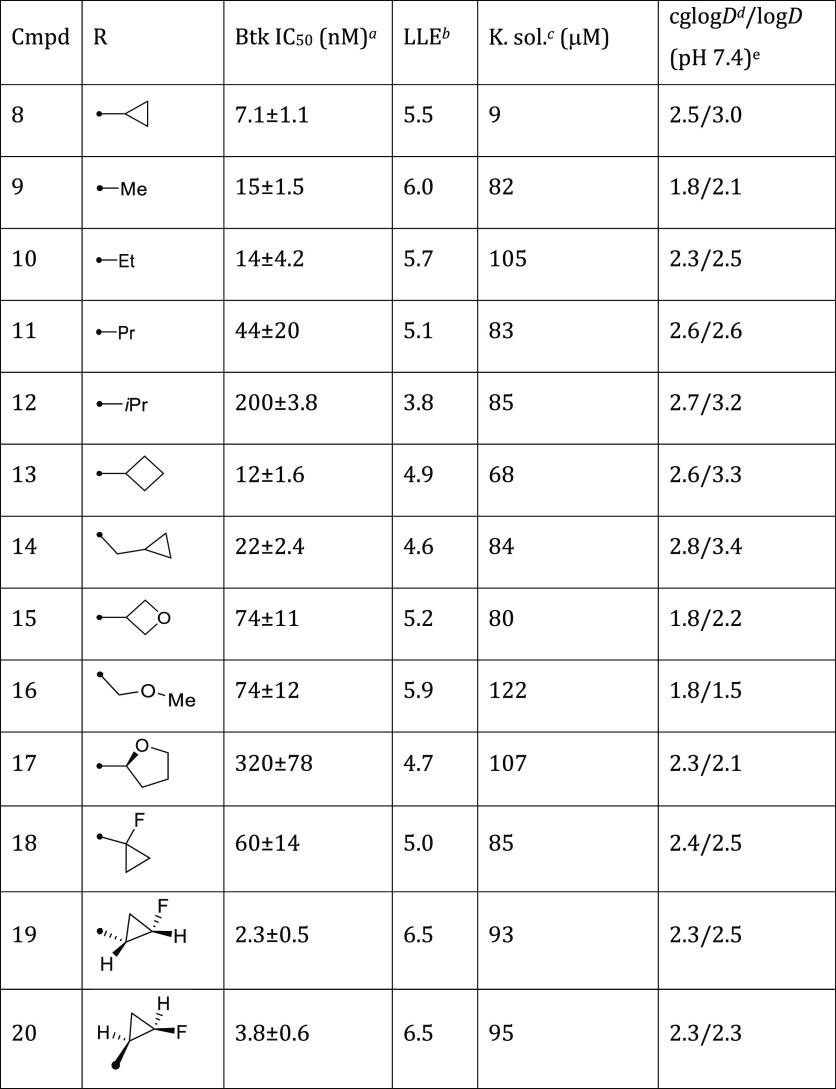

Our first amide analogue cyclopropanyl 8 inhibited Btk with an IC50 of 7.1 nM vs 2.3 (±0.7) nM for 6. A targeted library incorporating small amide substituents (Table 1, 8–17) was prepared from advanced intermediate 7. Cyclopropyl substitutions retained the greatest inhibitory potency against Btk (Table 1; assay protocols in Supporting Information). Kinetic solubility gave an initial gauge of intrinsic solubility.35 The initial cyclopropane amide 8 was the most potent amide in this series. Similarly sized short alkyl and cyclobutyl analogs (9–11, 13–14) were less potent than the cyclopropyl. Branched alkyl i-Pr (12) was even less potent and was likely too bulky to fit into the narrow pocket previously occupied by a flat, aryl group. Added polarity with oxetane, methoxy, or tetrahydrofuran substitution (15–17, respectively) drastically decreased potency.

Table 1. Amide-Based 2-Aminopyridine Replacements in the Btk H2 Pocket.

IC50 values (mean ± SD) were determined in at least triplicate. See Supporting Information for assay details.

LLE = pIC50(Btk) – cgLogD.

Kinetic solubility at pH 7.4.

Calculated logD using MoKa program v2 (www.moldiscovery.com).

LogD measured using a high throughput microscale shake flask with LC tandem MS quantitation.

Cognizant of the tight SAR and seeking to improve upon the potency of 8, we postulated that the incorporation of fluorine atoms on the cyclopropane might be tolerated and could improve physicochemical properties.36,37 Fluoro substitution at the tertiary carbon in 18 resulted in a significant loss in Btk potency (IC50 = 60 nM), possibly due to a then-hypothesized loss of a nonclassical H-bond between the cyclopropyl C–H and the hinge (Figure 3). In contrast, the cis-2-fluoro cyclopropane showed improved potency, with the (S,S)-enantiomer 19 (IC50 = 2.3 nM) slightly more active than the (R,R)-enantiomer 20 (IC50 = 3.8 nM). Additionally, both 19 and 20 demonstrated improved kinetic solubility over 8. Illustrative of the improved potency and decreased lipophilicity, the LLE increased by a log unit. This is indicative of a specific interaction with the protein rather than the simple lipophilic partitioning that might have been expected from the introduction of the cyclopropyl motif.38

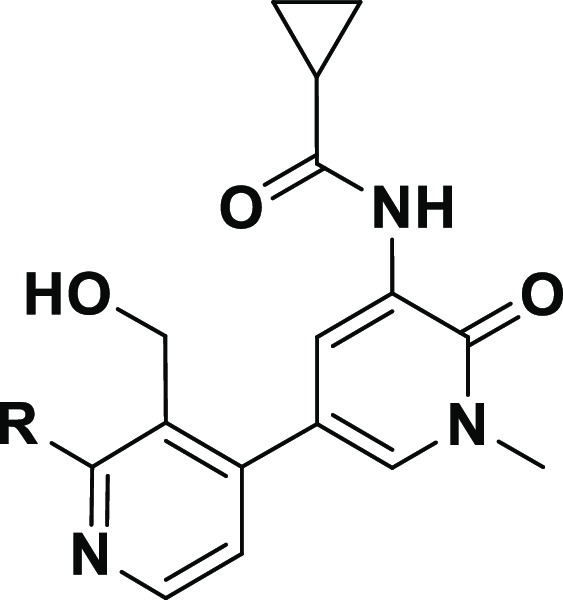

Seeking to improve our preclinical inhibitors by optimally balancing physicochemical properties and potency, we synthesized a set of analogs containing the simple cyclopropyl amide combined with potent H3 selectivity pocket motifs (Table 2).25,39 Compound 21 with a more polar H3 motif lost potency (IC50 = 98 nM) while pyridazinone-fused tetrahydrobenzothiophene 22 (IC50 = 7.7 nM) was equipotent to 8 (IC50 = 7.1 nM). However, the potency of 22 to prevent BCR-dependent B cell activation in human whole blood, assessed by monitoring anti-IgM-induced CD69 expression on B cells (CD69 IC50 = 1100 nM) was ∼8-fold less than 8 (CD69 IC50 = 140 nM). In contrast, t-butyl phthalazinone 23 possessed improved biochemical (IC50 = 4.8 nM) and whole blood (CD69 IC50 = 78 nM) potency. Additionally, 23 had improved solubility (76 μM) over 8 (9 μM) and was stable in human and rat liver microsomes (HLM 3.2, RLM 13 mL/min/kg).

Table 2. H3 Selectivity Pocket SAR.

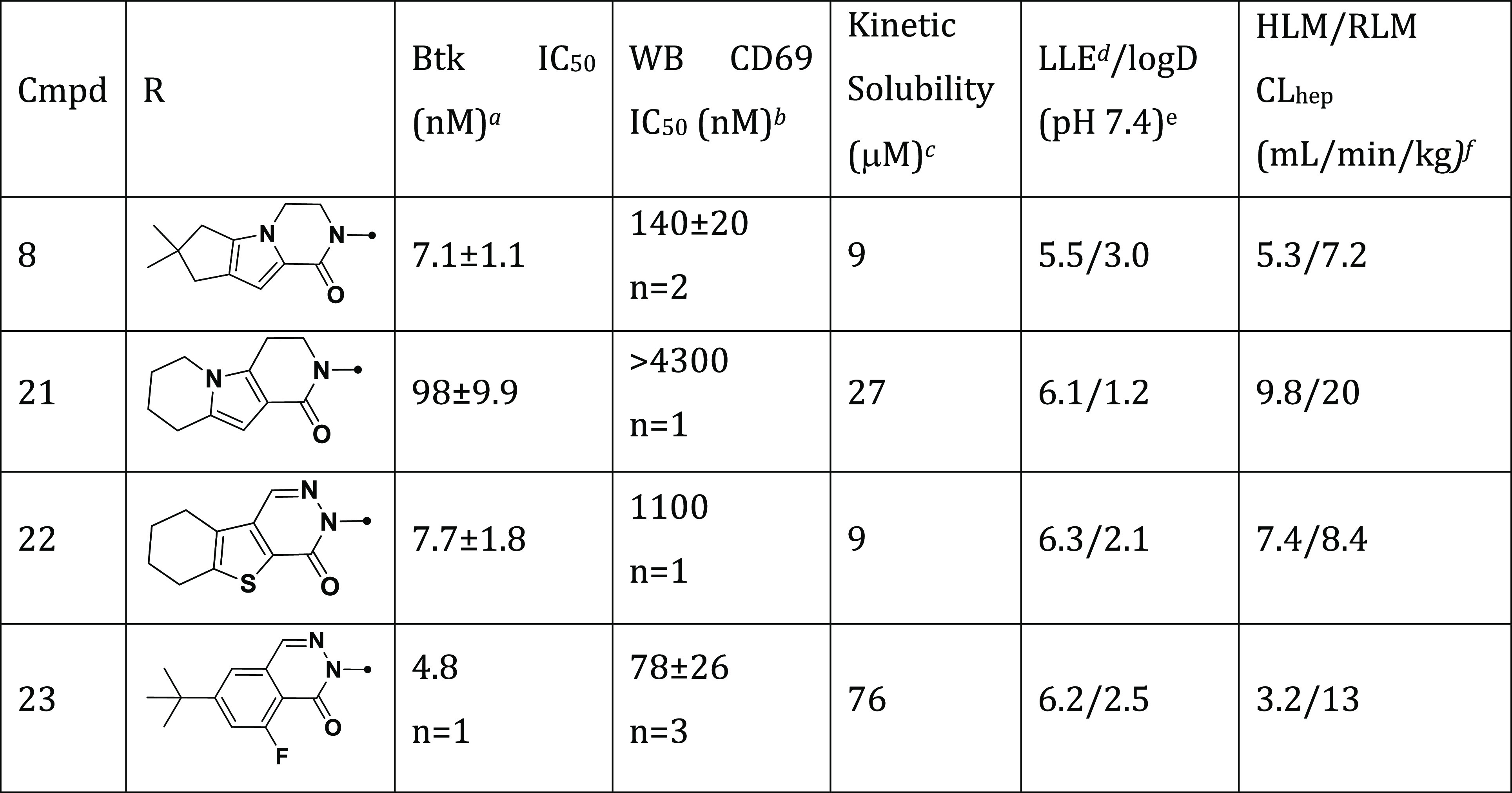

The tert-butyl phthalazinone H3 was combined with all four stereoisomers of the 2-fluoro substituted cyclopropyl amide (Table 3). The cis-fluoro isomers 24 and 25 were nearly equipotent against Btk (IC50 = 3.2 and 2.4 nM, respectively) relative to unsubstituted cyclopropane 23 (IC50 = 4.8 nM). Conversely, the trans-fluoro isomers 26 and 27 were less potent against Btk and in human whole blood CD69 and offered no advantages over 23. In whole blood the (S,S)-enantiomer 25 was twice as potent as the (R,R)-enantiomer 24. Of the four diastereomers, cis (S,S)-isomer 25 offered the best LLE (7.3) and kinetic solubility (107 μM) with high permeability (MDCK Papp A:B 12.5 × 10–6 cm/s) and good stability in both rat (RLM 11 mL/min/kg) and human liver microsomes (HLM 8 mL/min/kg). As a final optimization step we studied the effect of changes to the key hinge-binding heterocycle. Replacement of the pyridone with pyrazinone 28 and pyridazinone 29 could influence physicochemical properties such as logD,40 but these changes were deleterious to both biochemical and whole blood potency.

Table 3. Single Stereoisomers of 2-Fluorocyclopropyl Amides with the tert-Butyl-phthalazinone H3 Motif and Core Heterocycle SAR.

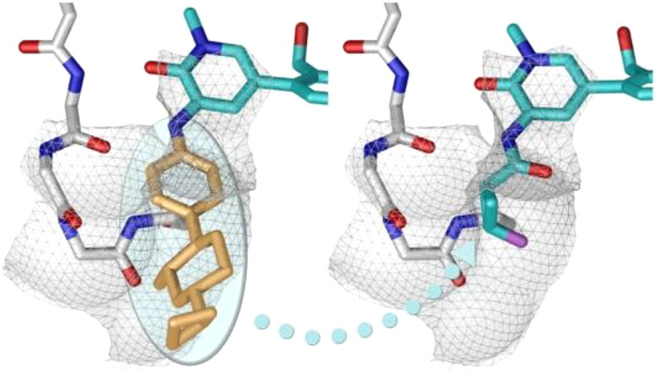

We solved a 1.6-Å resolution X-ray cocrystal structure of 25 bound to Btk (Figure 4). The compound formed extensive van der Waals and hydrogen bonding interactions within the active site. As predicted, 25 formed hydrogen bonds between the pyridone carbonyl and the Met477 amide backbone NH of the hinge. Additionally, the participation of the cyclopropane’s polarized, tertiary hydrogen in a dipole-induced dipole to the carbonyl of Met477 (Figure 4a) was confirmed. As shown by our modeling, a cyclopropane fits well in the H2 region, bisecting the plane previously occupied by the pyridine ring and resulting in favorable van der Waals interactions with the protein surface (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

X-ray cocrystal structure of 25 bound to Btk. (a) Two predicted hydrogen bonds to the hinge are present along with an additional favorable CH-carbonyl interaction between the c-propyl proton and the Met477 backbone carbonyl (pink dashed line). (b) The c-propyl forms complementary van der Waals interactions with the protein surface.

Given the excellent biochemical and whole blood potency, as well as in vitro pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of 25, we further profiled and compared it to our (later) clinical stage inhibitor, fenebrutinib, 6 (Table 4). The Btk potency of 25 was similar to 6, while the whole blood potencies of 25, both anti-IgM-induced CD69 expression on B cells and Btk Y223 autophosphorylation, were 10-fold and 7-fold less potent than 6, respectively, likely driven by the previously reported time dependent inhibition of Btk by 6. Although not as potent in the whole blood CD69 and pBtk assays relative to 6, cyclopropane carboxamide 25 had improved kinetic (≥100 μM) and thermodynamic (27 μM) solubility vs 6. We next assessed the in vivo PK of 25 in rats and dogs. In rats, 25 (0.2 mg/kg IV and 1.0 mg/kg PO, amorphous suspension) had low plasma clearance (13 mL/min/kg), moderate bioavailability (F = 40%), and comparable unbound clearance (283 mL/min/kg) to 6 (314 mL/min/kg). At a dose of 5.0 mg/kg in rats, crystalline 25 in aqueous suspension gave just F = 7%, but this improved 10-fold to 72% when dosed as an amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) suspension, showing promise as a potential development candidate using this technology. Further, 25 had excellent in vivo PK in dogs (1.0 mg/kg IV and 2.0 mg/kg PO, amorphous suspension) with low plasma clearance (2 mL/min/kg for 25) and complete oral bioavailability (F = 123%) when dosed as an ASD suspension. Furthermore, 25 showed no CYP450 inhibition or induction liability. Cyclopropylcarboxylic acid has been identified as a potential toxicophore, via inhibition of mitochodrial function and/or incorporation into the TCA cycle.41,42 We conducted in vitro metabolite identification studies to assess the metabolic stability of the amide, whereby 25 was incubated at 5 μM concentration in cryopreserved human, rat, and dog hepatocytes (∼1.0 × 106 cells/mL) for 3 h. In each case ≤1% amide hydrolysis was observed.

Table 4. Profiles of 25 and 6.

| 25 | 6 (fenebrutinib) | |

|---|---|---|

| Btk IC50/LLE | 2.4 nM/7.3 | 2.3 nM/7.4 |

| CD69 HWB IC50 | 78 nM | 8 nM |

| pBtk HWB IC50 | 78 nM | 11 nM |

| MW/mLogD/clogP | 536/1.6/1.4 | 665/1.6/2.2 |

| Kin.; T. Solubility | 107 μM; 100 μM | 67 μM; 2 μM |

| MDCK Papp A:B (10–6 cm/s) | 12.1 | 15.1 |

| LM CLhep (H/R/D) (mL/min/kg) | 8/11/20 | 9.5/14/29 |

| Hep CLhep (H/R/D) (mL/min/kg) | 6.2/11/<21 | 9.3/10/<21 |

| CYP inhibition (5 isoforms) | All >10 μM | All >10 μM |

| Rat PK: iv CLp, Fa | 15 mL/min/kg, 40% | 22 mL/min/kg, 96% |

| Rat Clu | 326 mL/min/kg | 314 mL/min/kg |

| Dog PK: iv CLp | 2 mL/min/kg | 12 mL/min/kg |

| PO, F/doseb | 123%/2 mg/kg | 130%/5 mg/kg |

| Kinase Sel. (Hits >50% at 1 μM) | 1/220 | 3/295 |

| hERG IC50 | 1.3 μM | >30 μM |

Dosed 1 mg/kg PO was dosed as a cassette ASD suspension, made by lyophilization.

Dosed 2 mg/kg as an ASD suspension, discrete dosing, made via spray drying.

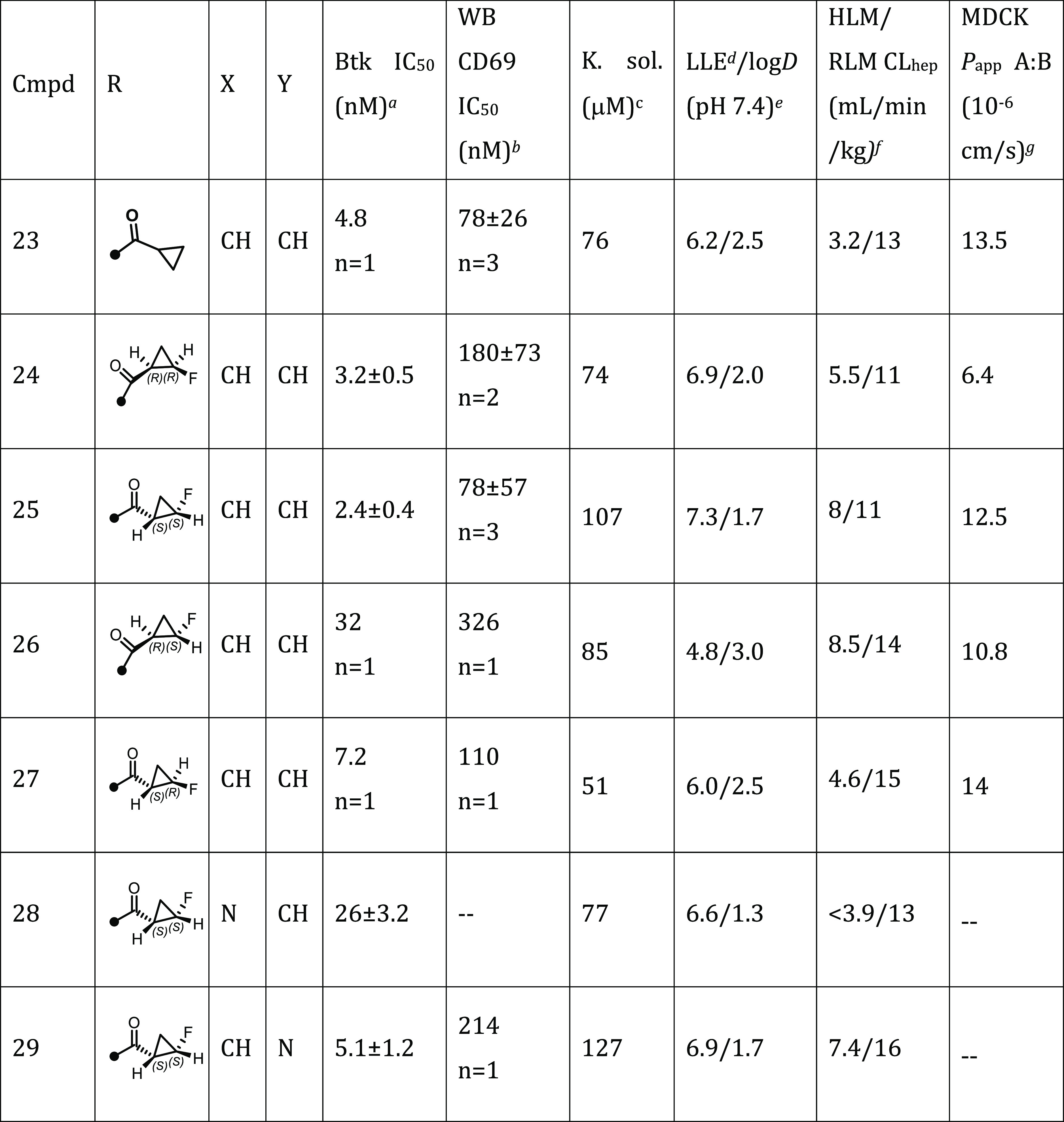

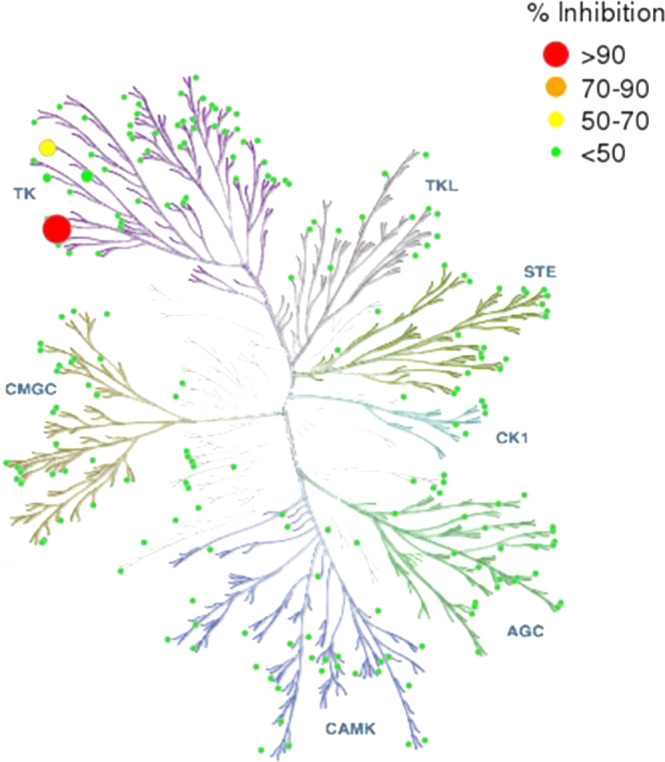

Compound 25 demonstrated exquisite Btk selectivity when tested at 1 μM against 220 human kinases (Figure 5), showing >50% inhibition of only one off-target kinase, Src, and minimal inhibition of Fgr and Bmx, two off-targets of 6 (Tables S1, S2). Based on IC50 values, compound 25 is greater than 550-fold selective for inhibition of Btk over Src.

Figure 5.

Kinome tree representation of kinase selectivity of 25 at 1 μM.

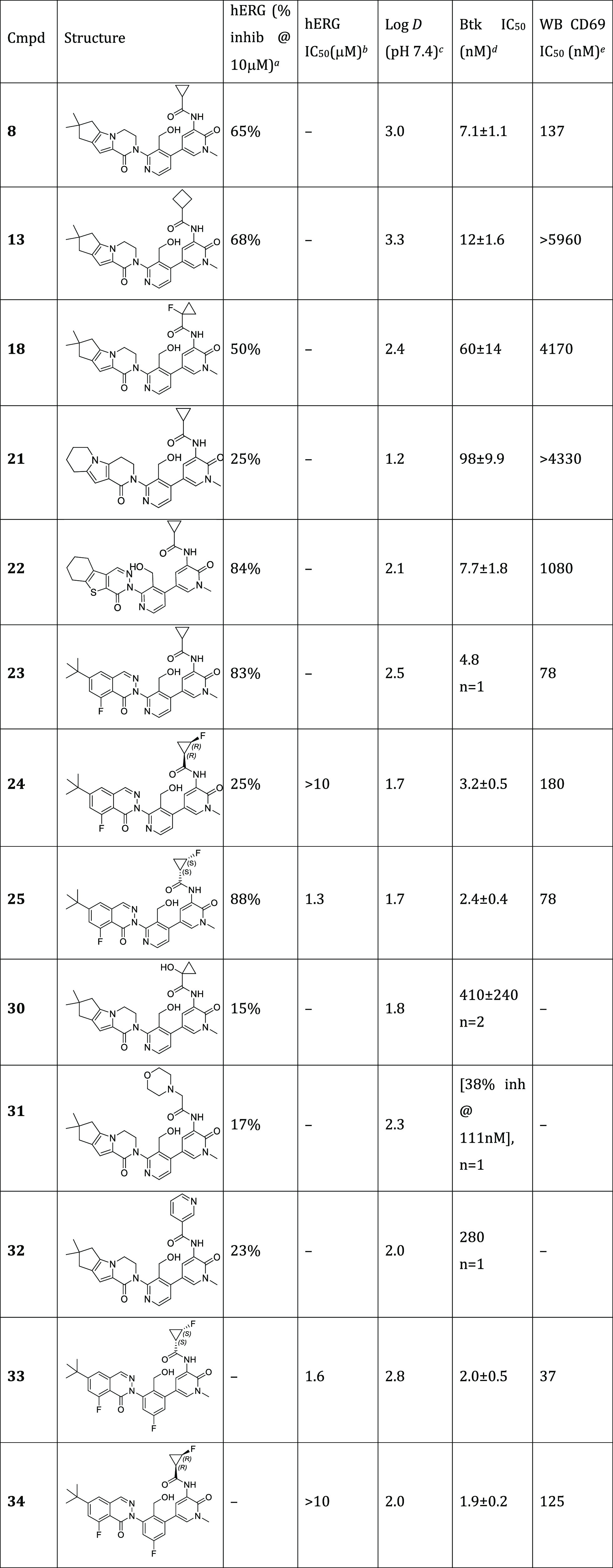

Our enthusiasm for 25 was tempered by the finding that it inhibited the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel current (IC50 = 1.3 μM). It is known that hERG blockade is the most common mechanism of acquired (drug-induced) long QT syndrome and torsades de pointes arrhythmia.43,44 We thus set out to investigate the SAR with the goal of attenuating the observed hERG inhibition (Table 5).

Table 5. hERG SAR Profile of Amide-H2 Btk Inhibitors (% Inhibition @ 10 μM).

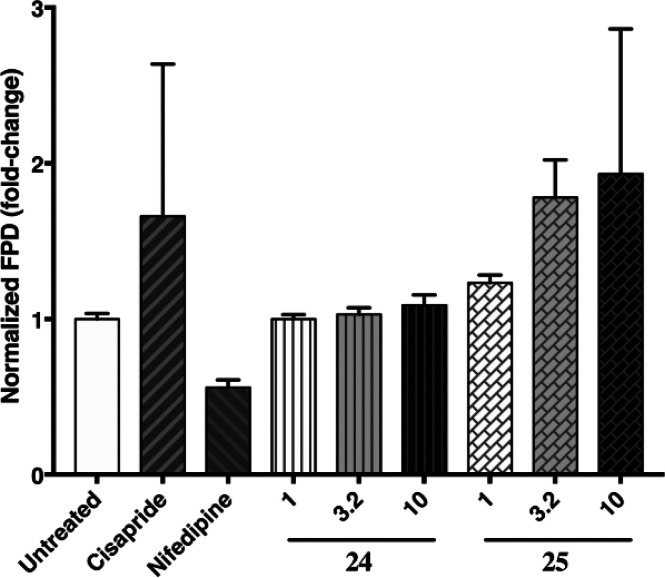

Substitution on both the H2 and amide motifs dramatically decreased the inhibitory effect of compounds on hERG. Since hERG risk often increases with increasing lipophilicity44−46 we first examined the effect of different H3 groups on hERG inhibition at 10 μM (Table 5, compounds 8, 21–23). Most of the H3 groups on the cyclopropyl amide showed significant hERG inhibition (≥60% inhibition) with the exception of 21, in line with its reduced lipophilicity. Although 21 significantly reduced hERG blockade (25%@10 μM), it lacked the desired level of Btk potency (IC50 = 98 nM). We next evaluated different amides (13, 18, 30–32) while utilizing the H3 lipophilic pocket motif from fenebrutinib (6). Again, hERG inhibitory potency was reduced with this more polar motif (lower log D). Interestingly, while compound 25 showed 88% hERG inhibition at 10 μM, its enantiomer, (R,R) isomer 24, seemed to exhibit a significantly attenuated effect (25%@10 μM). The hERG IC50 of 24 was confirmed to be >10 μM, >6× less potent against hERG compared with 25. To confirm that the reduction in hERG inhibition relative to 25 is biologically meaningful, 24 and 25 were assessed by multielectrode array using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes. Consistent with strong hERG blockade, 25 demonstrated substantial prolongation of field potential duration (FPD) (80 and 90% increase at 3.2, 10 μM, respectively). In contrast, no change in FPD was observed with up to 10 μM of 24 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Drug-induced field potential shift in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes: 24 vs 25. Field potential duration (FPD) was measured in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes after 1 h of compound treatment. 24 and 25 were tested at 1, 3.2, and 10 μM. N = 4, error bars represent SEM.

The significant reduction in hERG inhibition with the (R,R) stereoisomer 24 was intriguing. In contrast to the observed LLE advantage obtained with (S,S)-25, stereoisomer 24 suffered a 2-fold loss in CD69 potency. Exploiting previously reported SAR, we anticipated that replacing the pyridyl linker of 25 with a fluoro-aryl linker (33) would improve the potency. Indeed, 33 was twice as potent (CD69 IC50 = 37 nM) as 25 (CD69 IC50 = 78 nM) (Table 5). However, strong hERG inhibition was also observed (IC50 1.6 μM) for this (S,S)-stereoisomer 33. Hoping to improve the potency of the corresponding (R,R)-isomer, fluoroaryl 34 was prepared. Indeed, the Btk potency improved (IC50 = 1.9 nM for 34 vs 3.2 nM for 24), as did the whole blood potency (CD69 IC50 = 125 nM for 34 vs 180 nM for 24). Interestingly 34 showed no discernible hERG liability (hERG IC50 > 10 μM) or prolongation of FPD at up to 3.2 μM (solubility limited). While differences between enantiomers in the hERG blockade have been observed,47 this example is unusual in that the parent compounds would be expected to be neutral at physiological pH.

To conclude, replacement of the interaction features of a pyridyl ring with a cyclopropyl amide resulted in a structurally differentiated subseries of noncovalent BTK inhibitors. SAR investigations and subsequent combination with a (t-butyl)-phthalazinone H3 motif led to the identification of 25, a potent 2-fluoro-cyclopropylamide Btk inhibitor with attractive physicochemical properties, excellent kinase selectivity, and favorable oral pharmacokinetics in rat and dog. A potential liability of these inhibitors was identified in the form of hERG blockade that was found to be sensitive to stereochemistry, where the (R,R)-stereoisomers were found to be at least 6-fold less active when compared to their (S,S)-isomers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zoe Zhong, Aaron Fullerton, Orlando Zuniga, Suzanne Tay, Ivy Chen, Pawan Bir Kohli, and Sergei Romanov (Nanosyn) for their assistance in gathering and reviewing data and Snahel Patel and Drs Gampe, Parr, Grandner, Landry, and Mackenzie for helpful comments. X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamline 21-IDF operated by the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- cglogD

calculated logD (Genentech)

- pBtk

phosphorylated Btk whole blood assay

- MDCK Paap

Madin–Darby canine kidney apparent permeability

- HWB

human whole blood

- kinase sel.

kinase selectivity

- Bmx

bone marrow tyrosine kinase on chromosome X

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00249.

Experimental procedures, compound characterization, in vitro pharmacology, kinase selectivity profiling, in vivo methods, and crystallography details (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Thanks to Genentech for funding this work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The authors are, or were, employees of Genentech/Roche and hold/have held shares in Roche.

Supplementary Material

References

- Satterthwaite A. B.; Li Z.; Witte O. N. Btk Function In B Cell Development and Response. Semin. Immunol. 1998, 10, 309–316. 10.1006/smim.1998.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan W. N. Regulation of B Lymphocyte Development and Activation by Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. Immunol. Res. 2001, 23, 147–156. 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U.; Boucheron N.; Unger B.; Ellmeier W. The Role of Tec Family Kinases in Myeloid Cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2004, 134, 65–78. 10.1159/000078339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner C.; Müller B.; Wirth T. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase is Involved in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Histol. Histopathol. 2005, 20, 945–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo J. A.; Huang T.; Balazs M.; Barbosa J.; Barck K. H.; Bravo B. J.; Carano R. A. D.; Darrow J.; Davies D. R.; DeForge L. E.; Diehl L.; Ferrando R.; Gallion S. L.; Giannetti A. M.; Gribling P.; Hurez V.; Hymowitz S. G.; Jones R.; Kropf J. E.; Lee W. P.; Maciejewski P. M.; Mitchell S. A.; Rong H.; Staker B. L.; Whitney J. A.; Yeh S.; Young W. B.; Yu C.; Zhang J.; Reif K.; Currie K. S. Specific Btk Inhibition Suppresses B Cell- And Myeloid Cell-Mediated Arthritis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 41–50. 10.1038/nchembio.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite A. B.; Witte O. N. The Role of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase in B-cell Development and Function: A Genetic Perspective. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 175, 120–127. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2000.imr017504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri K. D.; Di Paolo J. A.; Gold M. R. B-cell Receptor Signaling Inhibitors for Treatment of Autoimmune Inflammatory Diseases and B-cell Malignancies. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 32, 397–427. 10.3109/08830185.2013.818140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katewa A.; Wang Y.; Hackney J. A.; Huang T.; Suto E.; Ramamoorthi N.; Austin C. D.; Bremer M.; Chen J. Z.; Crawford J. J.; Currie K. S.; Blomgren P.; DeVoss J.; DiPaolo J. A.; Hau J.; Johnson A.; Lesch J.; DeForge L. E.; Lin Z.; Liimatta M.; Lubach J. W.; McVay S.; Modrusan Z.; Nguyen A.; Poon C.; Wang J.; Liu L.; Lee W. P.; Wong H.; Young W. B.; Townsend M. J.; Reif K. Btk-Specific Inhibition Blocks Pathogenic Plasma Cell Signatures and Myeloid Cell-Associated Damage in IFN-α Driven Lupus Nephritis. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e90111 10.1172/jci.insight.90111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg L. A.; Smith A. M.; Sirisawad M.; Verner E.; Loury D.; Chang B.; Li S.; Pan Z.; Thamm D. H.; Miller R. A.; Buggy J. J. The Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor PCI-32765 Blocks B Cell Activation and is Efficacious in Models of Autoimmune Disease and B-cell Malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 13075–13080. 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Di Paolo J.; Barbosa J.; Rong H.; Reif K.; Wong H. Antiarthritis Effect of a Novel Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) Inhibitor in Rat Collagen-Induced Arthritis and Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling: Relationships Between Inhibition of BTK Phosphorylation and Efficacy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 338, 154–163. 10.1124/jpet.111.181545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E. K.; Tester R.; Aslanian S.; Karp R.; Sheets M.; Labenski M. T.; Witowski S. R.; Lounsbury H.; Chaturvedi P.; Mazdiyasni H.; Zhu Z.; Nacht M.; Freed M. I.; Petter R. C.; Dubrovsky A.; Singh J.; Westlin W. F. Inhibition of Btk with CC-292 Provides Early Pharmacodynamic Assessment of Activity in Mice and Humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 346, 219–228. 10.1124/jpet.113.203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D.; Kim Y.; Postelnek J.; Vu M. D.; Hu D.-Q.; Liao C.; Bradshaw M.; Hsu J.; Zhang J.; Pashine A.; Srinivasan D.; Woods J.; Levin A.; O’Mahony A.; Owens T. D.; Lou Y.; Hill R. J.; Narula S.; DeMartino J.; Fine J. S. RN486, a Selective Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, Abrogates Immune Hypersensitivity Responses and Arthritis in Rodents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 341, 90–103. 10.1124/jpet.111.187740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina-Osorio P.; LaStant J.; Keirstead N.; Whittard T.; Ayala J.; Stefanova S.; Garrido R.; Dimaano N.; Hilton H.; Giron M.; Lau K. Y.; Hang J.; Postelnek J.; Kim Y.; Min S.; Patel A.; Woods J.; Ramanujam M.; DeMartino J.; Narula S.; Xu D. Suppression of Glomerulonephritis in Lupus-Prone NZB × NZW Mice by RN486, a Selective Inhibitor of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2380–2391. 10.1002/art.38047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson J.; Vanarsa K.; Bashmakov A.; Grewal S.; Sajitharan D.; Chang B. Y.; Buggy J. J.; Zhou X. J.; Du Y.; Satterthwaite A. B.; Mohan C. Modulating Proximal Cell Signaling by Targeting Btk Ameliorates Humoral Autoimmunity and End-Organ Disease in Murine Lupus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R243. 10.1186/ar4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin A. L.; Seth N.; Keegan S.; Andreyeva T.; Cook T. A.; Edmonds J.; Mathialagan N.; Benson M. J.; Syed J.; Zhan Y.; Benoit S. E.; Miyashiro J. S.; Wood N.; Mohan S.; Peeva E.; Ramaiah S. K.; Messing D.; Homer B. L.; Dunissi-Joannopoulos K.; Nickerson- Nutter C. L.; Schnute M. E.; Douhan J. III Selective Inhibition of Btk Prevents Murine Lupus and Antibody-Mediated Glomerulonephritis. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 4540–4550. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A. T.; Pereira A.; Fu K.; Samy E.; Wu Y.; Liu-Bujalski L.; Caldwell R.; Chen Y. Y.; Tian H.; Morandi F.; Head J.; Koehler U.; Genest M.; Okitsu S. L.; Xu D.; Grenningloh R. Btk Inhibition Treats TLR7/IFN Driven Murine Lupus. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 164, 65–77. 10.1016/j.clim.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers S. A.; Doerner J.; Bosanac T.; Khalil S.; Smith D.; Harcken C.; Dimock J.; Der E.; Herlitz L.; Webb D.; Seccareccia E.; Feng D.; Fine J. S.; Ramanujam M.; Klein E.; Putterman C. Therapeutic Blockade of Immune Complex-Mediated Glomerulonephritis by Highly Selective Inhibition of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26164. 10.1038/srep26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie K. S.Targeting the B-cell Receptor Pathway in Hematological Maligancies. In 2015 Medicinal Chemistry Reviews; Desai M. C., Ed.; American Chemical Society Division of Medicinal Chemistry: Washington, DC, 2016; pp 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z.; Scheerens H.; Li S.-J.; Schultz B. E.; Sprengeler P. A.; Burrill L. C.; Mendonca R. V.; Sweeney M. D.; Scott K. C. K.; Grothaus P. G.; Jeffery D. A.; Spoerke J. M.; Honigberg L. A.; Young P. R.; Dalrymple S. A.; Palmer J. T. Discovery of Selective Irreversible Inhibitors for Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 58–61. 10.1002/cmdc.200600221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Y.; O’Brien S. Acalabrutinib and its use in treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 579–589. 10.2217/fon-2018-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Zhang M.; Liu D. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196): a selective second-generation BTK inhibitor. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 21–24. 10.1186/s13045-016-0250-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Liu Y.; Hu N.; Yu D.; Zhou C.; Shi G.; Zhang B.; Wei M.; Liu J.; Luo L.; Tang Z.; Song H.; Guo Y.; Liu X.; Su D.; Zhang S.; Song X.; Hong Y.; Chen S.; Cheng Z.; Young S.; Wei Q.; Wang H.; Wang Q.; Lv L.; Wang F.; Xu H.; Sun H.; Xing H.; Li N.; Zhang W.; Wang Z.; Liu G.; Sun Z.; Zhou D.; Li W.; Liu L.; Wang L.; Wang Z. Discovery of Zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), a Novel, Potent, and Selective Covalent Inhibitor of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7923–7940. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W. B.; Barbosa J.; Blomgren P.; Bremer M. C.; Crawford J. J.; Dambach D.; Gallion S.; Hymowitz S. G.; Kropf J. E.; Lee S. H.; Liu L.; Lubach J. W.; Macaluso J.; Maciejewski P.; Maurer B.; Mitchell S. A.; Ortwine D. F.; Di Paolo J.; Reif K.; Scheerens H.; Schmitt A.; Sowell C. G.; Wang X.; Wong H.; Xiong J.-M.; Xu J.; Zhao Z.; Currie K. S. Potent and Selective Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Discovery of GDC-0834. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 1333–1337. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W. B.; Barbosa J.; Blomgren P.; Bremer M. C.; Crawford J. J.; Dambach D.; Eigenbrot C.; Gallion S.; Johnson A. R.; Kropf J. E.; Lee S. H.; Liu L.; Lubach J. W.; Macaluso J.; Maciejewski P.; Mitchell S. A.; Ortwine D. F.; Di Paolo J.; Reif K.; Scheerens H.; Schmitt A.; Wang X.; Wong H.; Xiong J.-M.; Xu J.; Yu C.; Zhao Z.; Currie K. S. Discovery of Highly Potent and Selective Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Pyridazinone Analogs With Improved Metabolic Stability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 575–579. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Barbosa J.; Blomgren P.; Bremer M. C.; Chen J.; Crawford J. J.; Deng W.; Dong L.; Eigenbrot C.; Gallion S.; Hau J.; Hu H.; Johnson A. R.; Katewa A.; Kropf J. E.; Lee S. H.; Liu L.; Lubach J. W.; Macaluso J.; Maciejewski P.; Mitchell S. A.; Ortwine D. F.; DiPaolo J.; Reif K.; Scheerens H.; Schmitt A.; Wong H.; Xiong J. M.; Xu J.; Zhao Z.; Zhou F.; Currie K. S.; Young W. B. Discovery of Potent and Selective Tricyclic Inhibitors of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase with Improved Druglike Properties. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 608–613. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson R. I.; Schutt L. K.; Tarrant J. M.; McDowell M.; Liu L.; Johnson A. R.; Lewin-Koh S.-C.; Hedehus M.; Ross J.; Carano R. A.; Staflin K.; Zhong F.; Crawford J. J.; Zhong S.; Reif K.; Katewa A.; Wong H.; Young W. B.; Dambach D. M.; Misner D. L. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Small Molecule Inhibitors Induce a Distinct Pancreatic Toxicity in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 360, 226–238. 10.1124/jpet.116.236224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J.; Johnson A. R.; Misner D. L.; Belmont L. D.; Castanedo G.; Choy R.; Coraggio M.; Dong L.; Eigenbrot C.; Erickson R.; Ghilardi N.; Hau J.; Katewa A.; Kohli P. B.; Lee W.; Lubach J. W.; McKenzie B. S.; Ortwine D. F.; Schutt L.; Tay S.; Wei B. Q.; Reif K.; Liu L.; Wong H.; Young W. B. Discovery of GDC-0853: A Potent, Selective, and Noncovalent Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor in Early Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2227–2245. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Crawford J. J.; Landry M. L.; Chen H.; Kenny J. R.; Khojasteh S. C.; Lee W.; Ma S.; Young W. B.. Strategies to Mitigate the Bioactivation of Aryl Amines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung L.; Kalgutkar A. S.; Obach R. S. Metabolic Activation in Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Drug Metab. Rev. 2012, 44, 18–33. 10.3109/03602532.2011.605791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J.; Lee W.; Young W. B.. Preparation of heteroaryl pyridone and aza-pyridone amide compounds. PCT Int. Appl. 2015, WO 2015000949 A1.

- Wood M. R.; Schirripa K. M.; Kim J. J.; Wan B.-L.; Murphy K. L.; Ransom R. W.; Chang R. S. L.; Tang C.; Prueksaritanont T.; Detwiler T. J.; Hettrick L. A.; Landis E. R.; Leonard Y. M.; Krueger J. A.; Lewis S. D.; Pettibone D. J.; Freidinger R. M.; Bock M. G. Cyclopropylamino Acid as a Pharmacophoric Replacement for 2,3-Diaminopyridine. Application to the Design of Novel Bradykinin B1 Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 1231–1234. 10.1021/jm0511280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moslin R.; Zhang Y.; Wrobleski S. T.; Lin S.; Mertzman M.; Spergel J. S.; Tokarski J. S.; Gillooly G.; McIntyre K. W.; Zupa-Fernandez A.; Cheng L.; Sun H.; Chaudhry C.; Huang C.; D’Arienzo C.; Heimrich E.; Yang X.; Muckelbauer J. K.; Chang C. Y.; Tredup J.; Mulligan D.; Xie D.; Aranibar A.; Chiney M.; Burke J. R.; Lombardo L.; Carter P. H.; Weinstein D. S. Identification of N-Methyl Nicotinamide and N-Methyl Pyridazine-3 Carboxamide Pseudokinase Domain Ligands as Highly Selective Allosteric Inhibitors of Tyrosine Kinase 2 (TYK2). J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 8953–8972. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. P.; Young R. J. Getting physical in drug discovery: a contemporary perspective on solubility and hydrophobicity. Drug Discovery Today 2010, 15, 648–655. 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S. E.; Beswick P. What does the aromatic ring number mean for drug design?. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2014, 9, 995–1003. 10.1517/17460441.2014.932346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B.; Pease J. H. A High Throughput Solubility Assay for Drug Discovery Using Microscale Shake-Flask and Rapid UHPLCUV-CLND Quantification. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 122, 126–140. 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K.; Faeh C.; Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: Looking beyond intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Synopsis of Some Recent Tactical Application of Bioisosteres in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2529–2591. 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz M. D. The Thermodynamic Basis for the Use of Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) in Enthalpic Optimizations. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5992–6000. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J.; Ortwine D. F.; Wei B.; Young W. B.. 8-Fluorophthalazin-1(2H)-one compounds as inhibitors of BTK activity and their preparation. PCT Int. Appl. 2013, WO 2013067264 A1, 20130510.

- Landry M. L.; Crawford J. J. LogD Contributions of Substituents Commonly Used in Medicinal Chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 72–76. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich R. G.; Bacon J. A.; Brass E. P.; Cramer C. T.; Petrella D. K.; Sun E. L. Metabolic, Idiosyncratic Toxicity of Drugs: Overview of the Hepatic Toxicity Induced by the Anxiolytic, Panadiplon. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2001, 134, 251–270. 10.1016/S0009-2797(01)00161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly R. A.; Ciurlionis R.; Morfitt D.; Helgren M.; Patterson R.; Ulrich R. G.; Waring J. F. Microvesicular Steatosis Induced by a Short Chain Fatty Acid: Effects on Mitochondrial Function and Correlation with Gene Expression. Toxicol. Pathol. 2004, 32 (2_suppl), 19–25. 10.1080/01926230490451699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampe D.; Brown A. M. A History of the Role of the hERG Channel in Cardiac Risk Assessment. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2013, 68, 13–22. 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest B.; Bell I. M.; Garcia M. Role of hERG Potassium Channel Assays in Drug Development. Channels 2008, 2, 87–93. 10.4161/chan.2.2.6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M. J.; Johnstone C. A Quantitative Assessment of hERG Liability as a Function of Lipophilicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1759–1764. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y.; Tsukamoto S.; Ito J.; Akimoto K.; Takahashi M. A Risk Assessment of Human Ether-a-go-go-related Gene Potassium Channel Inhibition by Using Lipophilicity and Basicity for Drug Discovery. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 1110–1116. 10.1248/cpb.59.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo L. S.; Carrupt P.-A.; Abriel H. Stereoselective Inhibition of the hERG1 Potassium Channel. Front. Pharmacol. 2010, 1, 1–11. 10.3389/fphar.2010.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.