Significance

Scholars and political commentators have often argued that business interests have privileged status in policy debates, particularly around questions of environmental degradation. However, few studies have been able to systematically compare business and advocacy organizations’ successful and unsuccessful attempts to influence political discourse, a key marker of interest group status. This study uses computational text analysis to fill this gap in the literature, examining the news coverage given to over 1,700 press releases about climate change from different types of organizations over an almost 30-y period. These results shed light on the social processes shaping the climate change debate in particular, while speaking to broader questions of how power is distributed in American democracy.

Keywords: climate change, politics, media, organizations, power

Abstract

Whose voices are most likely to receive news coverage in the US debate about climate change? Elite cues embedded in mainstream media can influence public opinion on climate change, so it is important to understand whose perspectives are most likely to be represented. Here, I use plagiarism-detection software to analyze the media coverage of a large random sample of business, government, and social advocacy organizations’ press releases about climate change (n = 1,768), examining which messages are cited in all articles published about climate change in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today from 1985 to 2014 (n = 34,948). I find that press releases opposing action to address climate change are about twice as likely to be cited in national newspapers as are press releases advocating for climate action. In addition, messages from business coalitions and very large businesses are more likely than those from other types of organizations to receive coverage. Surprisingly, press releases from organizations providing scientific and technical services are less likely to receive news coverage than are other press releases in my sample, suggesting that messages from organizations with greater scientific expertise receive less media attention. These findings support previous scholars’ claims that journalistic norms of balance and objectivity have distorted the public debate around climate change, while providing evidence that the structural power of business interests lends them heightened visibility in policy debates.

Whose voices are most likely to receive news coverage in the US debate about climate change, and what leads them to receive heightened visibility? Answering these questions is important because media representations of climate change can influence public understanding, public opinion, and willingness to engage personally or politically on this vital social issue (1–3). In particular, media coverage can affect public opinion by increasing the salience of cues from politicians, advocacy organizations, and other elites about whether citizens should be concerned about climate change and what the societal response should be (4, 5). For example, some scholars have suggested that disproportionate coverage of contrarian scientists* in mainstream media has played an important role in the protracted uncertainty around the reality and urgency of climate change among portions of the American public (6, 7). Understanding whose perspectives are most likely to be represented in mainstream news coverage of climate change can therefore lead to greater understanding of one important source of public disengagement and stalled national policy around climate change in the United States.

In addition, whether some types of interest groups have privileged status in policy debates is a question of long-standing concern in the study of politics (8–11). In particular, the extent and mechanisms through which businesses may exercise power, potentially eclipsing the efforts of citizens and advocacy groups, have been among the central issues in political science and sociology (12), including around questions of environmental degradation (13). However, few studies have been able to systematically compare business and advocacy organizations’ successful and unsuccessful attempts to influence political discourse, a key marker of interest group status.

Below, I investigate the visibility granted to different groups’ perspectives in the public debate about climate change by examining whether organizations’ press releases about climate change receive media attention in three major national newspapers. I use plagiarism-detection software to analyze the media coverage of a large random sample of business, government, and social advocacy organizations’ press releases about climate change (n = 1,768), examining which messages are cited in all articles published about climate change in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today from 1985 to 2014 (n = 34,948) (14). These techniques allow me to examine how organizations’ characteristics and the content of their messages affect which messages receive coverage in mainstream news outlets, as compared with those that do not. As others have noted (15, 16), this ability to compare “successful” messages with those that do not achieve media attention avoids many of the methodological problems, such as selection on the dependent variable, prevalent in framing and communications research. The results shed light on the social processes shaping the climate change debate in particular, while speaking to broader questions of how power is distributed in American democracy.

Previous research has suggested two prominent explanations for why the perspectives of some organizations or individuals are more likely to receive news coverage in the climate change debate than are others. First, journalistic norms of balance and objectivity can lead journalists to give equal voice to two sides in a debate (17–19). While ideally this “balance norm” is meant to ensure journalistic neutrality, in the case of climate change—where a large majority of scientists agree that climate change is occurring and is caused by human activity—following this norm means creating a highly distorted representation of the scientific understanding of the issue (18, 20–22). Accordingly, researchers have found that print and TV news outlets have historically overrepresented the extent of disagreement on the scientific basis of climate change, lending increased prominence and legitimacy to a small number of contrarian scientists (7, 17–20, 23, 24).

However, empirical support for the continuing relevance of the balance norm in shaping the media environment around climate change is mixed. Some studies suggest that the disproportionate visibility of opponents of climate action has declined or reversed since the issue rose in national prominence in the mid-2000s (25–27). In addition, other evidence suggests that the disproportionate visibility of contrarian scientists is concentrated among conservative newspapers and TV outlets (28–30). This would suggest that accord with editorial ideology rather than the application of journalistic norms may be responsible for the overrepresentation of advocates against climate action in mainstream media. On the whole, however, this work would suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Journalistic norms: Press releases advocating against action to address climate change will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls.†

Second, organizational power may lead the voices of large and wealthy organizations, and particularly those in extractive and polluting industries, to receive increased prominence in mainstream media. Three different types of power may facilitate media visibility of these organizations’ perspectives (12, 31–34). Instrumental power, or an organization’s access to human and monetary resources, may facilitate visibility by allowing organizations to expend more resources crafting and promoting policy messages, such as through the use of public relations personnel, lobbyists, or advertising agencies (35–39). In addition, these organizations may have leverage over other organizations or individuals, which they can use to influence policy debates (40). For example, large advertisers at news media outlets may be able to influence news coverage through their ability to withhold advertising revenue (1, 16). Consistent with the idea that organizational resource-dependence relations have shaped climate change discourse, Farrell (41) shows that organizations’ receipt of corporate funding is associated with increased use of polarizing themes over the course of the climate change debate.

Next, structural power, or an organization’s real or perceived importance in the functioning of the economy, can lead organizations’ actions and perspectives on policy issues to be seen as broadly relevant to public well-being (11, 42–44). In particular, the views of large employers are likely to be seen as newsworthy since these organizations could potentially respond to policy changes in ways that could cause economic disruption, such as through plant closures, large-scale layoffs, or offshoring (12, 45). Similarly, the policy positions of business coalitions and trade associations—as organizational forms aggregating shared interests within or across economic sectors—may receive heightened visibility to the extent that these organizations are seen as representing not simply one company’s perspective but instead, a broad swath of the economy (46, 47).

Finally, discursive power, or an organization’s perceived expertise and legitimacy, can lead some organizations’ perspectives to be seen as more relevant and credible than others in policy debates (33, 34, 48, 49). In particular, influential work in environmental sociology suggests that organizations involved in resource extraction and energy production have historically been given authority to define the terms of environmental debates (13). Research in this tradition argues that extractive and polluting industries’ narratives of the economic necessity of environmental degradation have privileged status in discussions of environmental issues, leading their perspectives to become ingrained as common sense (50–53). Meanwhile, other research suggests that natural scientists are seen as relevant authorities on environmental problems (21), such that we would expect the views of educational and scientific organizations to receive heightened media visibility.

Relatively little work has directly assessed whether the views of powerful organizations receive increased news coverage in the climate change debate. Instead, scholars have called for more attention to how power dynamics may affect policy framing and discourse, both in the case of climate change and in other policy debates (21, 54, 55). However, the importance of organizational power has been demonstrated empirically for a number of other organizational and political outcomes in a large cross-disciplinary literature (12, 40, 56–59). Therefore, I expect that instrumental, structural, and discursive power will influence whether organizations’ messages receive media visibility. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2. Instrumental power: Press releases originating from large organizations (in terms of employees, assets, and revenue) will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls.

Hypothesis 3. Structural power: Press releases originating from large businesses, business coalitions, and professional and trade associations will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls.

Hypothesis 4a. Discursive power (polluters): Press releases originating from businesses in extractive and highly polluting industries will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls.

Hypothesis 4b. Discursive power (scientists): Press releases originating from educational and scientific organizations will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls.

Methods

I compile a large random sample of business, government, and social advocacy organizations’ press releases about climate change from 1985 to 2013 (n = 1,768).‡ I match these messages with publicly available data about the type and size of each organization that issued a press release, and I code each press release according to whether it states support for or opposition to action to address climate change.§ I then use plagiarism-detection software to track which of these messages are quoted or paraphrased in all articles about climate change published in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today from 1985 to 2014 (total n = 34,948). The software identifies instances where strings of at least eight words closely or exactly match between two sets of documents (in this case, between press releases and newspaper articles), aiding in the identification of cases where the newspaper text may have derived from the press releases. Finally, I use multivariate regression analysis to examine how organizations’ characteristics and the content of their messages may affect which messages are cited in these newspaper articles and which are not.

The database of press releases and Stata code for replicating the analyses that follow have been deposited in the openICPSR Repository (accession no. 116561). More details on the methods are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

Results

Journalistic Norms: Overrepresentation of Messages Opposing Climate Action.

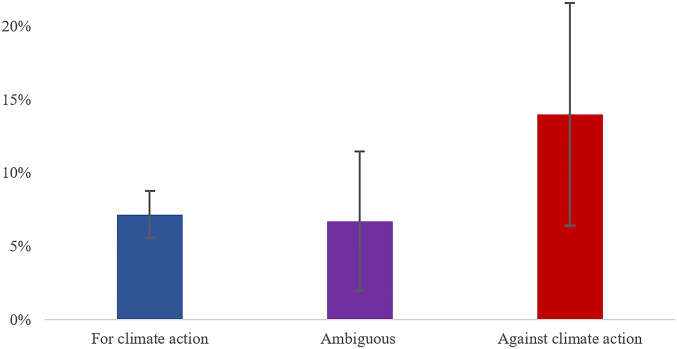

First, I test whether press releases advocating against action to address climate change receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls (Hypothesis 1). Controlling for industry and organizational size (in terms of employees, wealth, and revenue), I find that messages opposing climate action are significantly more likely to receive media coverage than are messages advocating for climate action (β = 0.836, P = 0.001) (SI Appendix, Table S1, model 5). Fig. 1 displays the predicted probabilities that organizations’ climate messages will receive newspaper coverage in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, or USA Today. While about 7.2% of messages advocating for action to address climate change are picked up by these national newspapers, this is true for almost twice the number of messages advocating against action to address climate change, or about 14.0%.

Fig. 1.

Probability of newspaper coverage by message content, controlling for other factors. Predicted values from logistic regression predicting newspaper coverage of press releases by specific organizational type, organization resources, and message characteristics. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Variables other than those describing message content are held at their means.

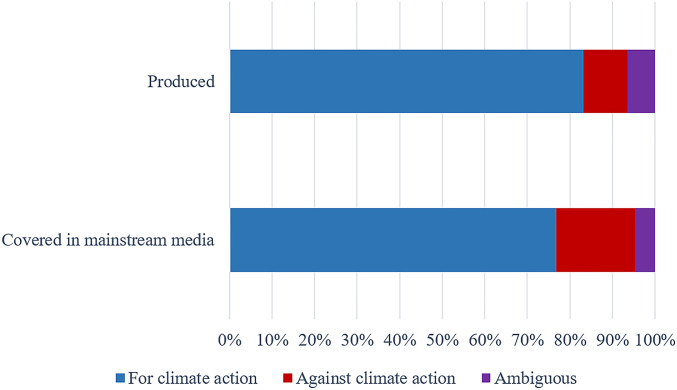

It is important to contextualize this finding by noting that messages advocating for climate action are much more prevalent among organizations’ press releases than are messages advocating against climate action. Descriptive statistics of all press releases suggest that messages against climate action are relatively rare, constituting only 10.4% of all press releases. As shown in Fig. 2, however, they are disproportionately likely to be covered in news outlets, such that they constitute about 18.4% of all press releases that receive media attention. These findings are consistent with the idea that journalistic norms of balance and objectivity lead media outlets to provide heightened visibility to viewpoints outside the mainstream—in this case, to messages that depart from the largely consensual view among business, government, and civil society organizations that climate change is a problem that is real, serious, and requires a societal response.

Fig. 2.

Climate messages produced by organizations vs. climate messages covered in major newspapers.

Contrary to some recent research suggesting that the balance norm has become less relevant to understanding the media environment around climate change, I find no indication that this disproportionate coverage of messages opposing climate action has declined or reversed since the mid-2000s. In addition, I find no evidence that this trend is driven primarily by the news coverage of The Wall Street Journal, the most ideologically conservative news outlet in my analysis. On the contrary, messages opposing climate action are given disproportionate coverage even in The New York Times, the most liberal newspaper I study.¶ This is consistent with the idea that journalistic norms of balance and objectivity rather than editorial ideology drive the overrepresentation of messages from opponents of climate action in mainstream media. However, it remains possible that the perspectives of opponents of climate action are framed or contextualized differently across news sources or over time. For example, Brüggemann and Engesser (25) find that journalists in recent years have begun to note that the views of contrarian scientists stand in contrast to the consensus of the scientific community, even while offering their perspectives in the news. For my purposes, a critical reference to an organization’s message is still considered as providing visibility to that interest group’s perspective.

An important issue to consider is that organizations’ statements may not reflect their true positions on climate change. In particular, businesses face widespread pressures toward expressing support for environmental sustainability and may see a strategic or reputational advantage in misrepresenting themselves as supportive of climate action when in fact they prefer the status quo (60–62). This could constitute a threat to the validity of these results if messages where an organization “insincerely” presents itself as supportive of climate action are particularly unsuccessful in receiving media attention.# This would lead me to underestimate the extent to which messages that are (sincerely) supportive of climate action have been able to receive media attention and so, to overstate the degree to which interests opposed to climate action have received greater visibility. In addition, this could plausibly be the case since journalists might know or suspect that these messages primarily serve strategic or reputational purposes—as in the commonly referenced practice of “greenwashing”—and so, avoid reporting on them.

I assess this possibility empirically by examining whether messages opposing climate action are more likely to receive media visibility only if they are released by businesses, or if messages opposing climate action receive heightened visibility when released by civil society organizations as well. If lower media coverage of “insincere” pro-climate messages was driving my findings, we would expect this effect to be concentrated among businesses conforming to norms of corporate social responsibility. We would not expect this to be the case among civil society organizations, however, where these norms are weaker or (in the case of conservative organizations) nonexistent and where journalists are unlikely to perceive potential greenwashing as a concern.

I present these robustness analyses in SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5. I find that messages opposing climate action are more likely to receive media coverage regardless of whether they come from businesses (SI Appendix, Table S4, models 1 and 2) or from civil society organizations (SI Appendix, Table S4, models 3 and 4).‖ In addition, the magnitude of the effect is statistically the same among businesses as among other types of organizations, as evidenced by interaction terms between message content and organization type that are substantively small and not statistically significant (SI Appendix, Table S5, models 1 to 4). While this analysis does not rule out the possibility that my results are affected by omitted variables bias, it alleviates concern that my results are driven by lower media coverage of messages where business interests feign support for environmental sustainability.**

Instrumental Power: No Significant Effects of Organizations’ Financial Resources.

Next, I test whether press releases originating from large organizations (in terms of employees, assets, and revenue) receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls (Hypothesis 2). I find that organizations’ assets and revenue are not significantly related to whether their messages are covered in national newspapers. In four different models with varying controls and specifications (SI Appendix, Tables S1, models 5 and 6 and S2, models 5 and 6), the effects of these variables, while positive, are small in magnitude and not statistically significant. I therefore find no evidence that messages from organizations with greater instrumental power in the form of access to financial resources receive heightened media visibility in news coverage of climate change.

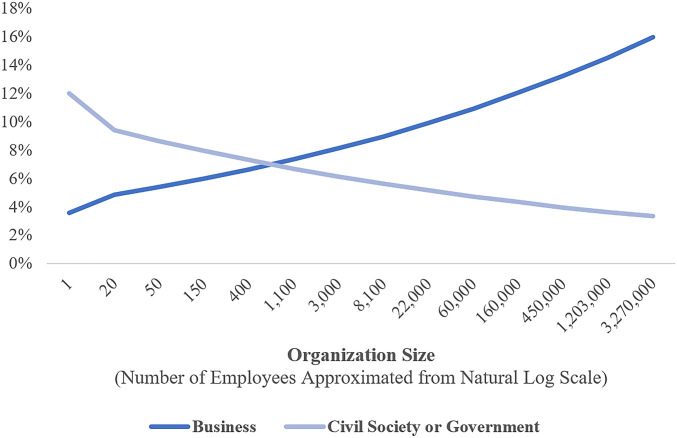

In contrast, I find that messages from organizations with larger numbers of employees are more likely to be picked up in national newspapers, but this effect is unique to businesses. In four different models with varying controls and specifications (SI Appendix, Tables S1, models 4 and 6 and S2, models 4 and 6), significant and positive interactions suggest that number of employees is related to media coverage, but the relationship is contingent on organization type. Fig. 3 displays the predicted probabilities that organizations’ climate messages will receive newspaper coverage by number of employees and organization type.

Fig. 3.

Probability of newspaper coverage by organization size, controlling for other factors. Predicted values from logistic regression predicting newspaper coverage of press releases by general organizational type, organization resources, and message characteristics. Variables other than those describing organizational type and organizational size are held at their means.

As shown in Fig. 3, press releases from businesses with larger numbers of employees are more likely to receive media coverage than are those from smaller business, but the opposite is true for civil society organizations and government agencies. Press releases from the largest businesses in my sample (those with about 3 million employees) have about a 16.0% chance of being cited in national newspaper articles, while those from the smallest businesses (those with fewer than 20 employees) have about a 3.6% chance. Conversely, press releases from smaller civil society organizations and government agencies are more likely to receive media coverage than are those from larger organizations of these types.

This finding may suggest that organizations’ perspectives can receive heightened news coverage when organizations have greater human resources to expend promoting their messages. However, that this effect is unique to businesses suggests another mechanism: these largest firms’ perspectives may receive heightened visibility because they are regarded as important players in the national economy. I discuss this possibility at greater length below.

Structural Power: Greater Coverage of Statements from Large Businesses, Business Coalitions, and Trade Associations.

Next, I test whether press releases originating from large businesses, business coalitions, and professional and trade associations receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls (Hypothesis 3). As discussed above and displayed in Fig. 3, I find that messages from large businesses are particularly likely to be quoted or paraphrased in national newspapers. In addition, I find that messages from business coalitions and professional and trade associations are more likely to receive media coverage than are messages from other types of organizations.

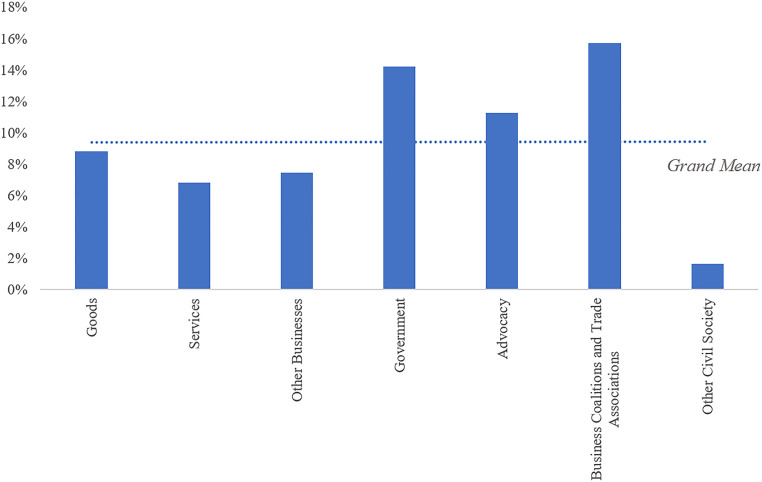

Fig. 4 displays descriptive statistics showing the percentage of press releases that are covered in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, or USA Today by general organizational type. As shown in Fig. 4, 15.7% of messages from business coalitions and professional and trade associations are covered by these national newspapers, as compared with 9.1% of messages from other types of organizations. In 8 of 12 different models with varying controls and specifications (SI Appendix, Tables S1, models 1 to 6 and S2, models 1 to 6), the proportion of press releases picked up from these types of organizations is significantly greater than the grand mean for organizations as a whole. In the other four models, these effects are marginally significant.

Fig. 4.

Climate messages covered in major newspapers by general organizational type.

These findings are consistent with the argument that organizations’ structural power, or their perceived importance in macroeconomic functioning, gives them disproportionate influence in policy debates. According to this line of reasoning, large businesses’ responses to policy changes have the potential to cause mass economic disruption, and so, their perspectives on political issues are more likely to be seen as newsworthy than are the views of other types of organizations. Likewise, one important function of business coalitions and professional and trade associations is to present the shared interests of stakeholders across organizational lines and sometimes across economic sectors. Therefore, policy statements promoted by organizations of these types may receive heightened visibility in policy debates because their perspectives are seen as broadly relevant to public well-being.

Discursive Power: No Evidence of Polluters’—or Scientists’—“Privileged Accounts”.

Next, I test whether press releases originating from businesses in extractive and highly polluting industries will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls (Hypothesis 4a). I find that these organizations’ messages are no more or less likely to be covered in national newspapers than are the messages of other types of organizations. In four different models with varying controls and specifications (SI Appendix, Table S3, models 1 to 4), the effects of this variable, while mostly positive, are not statistically significant. I therefore find no evidence for Freudenburg’s (13) influential assertion that organizations that disproportionately benefit from access to natural resources provide privileged accounts of environmental issues.

Finally, I test whether press releases originating from educational and scientific organizations will receive greater news coverage than other press releases, net of controls (Hypothesis 4b). I find that messages from educational organizations are no more or less likely to receive news coverage than the messages of other types of organizations. In addition, I find that messages from organizations providing scientific and technical services are significantly less likely to be reproduced in national newspapers than are the messages of other organizations. In six different models with varying controls and specifications (SI Appendix, Table S2, models 1 to 6), the proportion of press releases picked up from these types of organizations is significantly lower than the grand mean for organizations as a whole.

In fact, descriptive statistics suggest that statements from organizations providing professional, scientific, and technical services are among the least likely to be covered in mainstream news. Examples of these types of organizations include the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, the American Geophysical Union, Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In my sample, only 2.9% of messages from these scientific and technical organizations are picked up by national newspapers, as compared with 9.8% of messages from organizations as a whole. This finding is surprising, suggesting that the perspectives of organizations with presumably greater expertise to speak to the scientific issues around climate change are afforded less media attention than are the perspectives of other organizations.

Discussion

Asking whose voices are most likely to “make the news” in the US debate on climate change, I use plagiarism-detection software to investigate which of a large, random sample of press releases appear in over 30,000 articles about climate change in three national newspapers over an almost 30-y period. I find that statements from business coalitions and very large businesses are more likely than those from other types of organizations to receive news coverage. In addition, messages opposing climate action are about twice as likely as those advocating for climate action to be reproduced in mainstream media. These findings are consistent with previous scholars’ claims that the structural power of business interests and journalistic norms of balance and objectivity have distorted the public debate around climate change. Surprisingly, I also find that messages from organizations providing scientific and technical services are among the least likely to receive news coverage of the press releases in my sample, suggesting that an organization’s perceived scientific expertise is associated with less—not more—media visibility in the US climate change debate.

This study makes several advances over the existing literature. First, my use of computational methods allows me to examine a large sample of texts over a long timescale and across three major news sources with varying ideological viewpoints. This allows for greater representativeness and generalizability than most previous studies. In addition, I avoid the selection on the dependent variable problem present in most studies of media framing, where scholars analyze the characteristics of messages and speakers that appear in news media without comparing them with the broader population of messages and speakers that attempted to gain media visibility. Examining press releases that were and were not picked up in mainstream news sources allows me to identify the characteristics of messages that were successful in breaking into mainstream discourse, as compared with those that were not. Together, these methodological advances allow me to test long-standing hypotheses about how likely different types of interest groups are to successfully influence policy debates, contributing to academic and popular discussions about the dominance of business power in American politics.

I find that climate messages from large businesses and business coalitions receive greater media coverage in the American climate change debate than do messages from other types of organizations. Pragmatically, this finding is significant because heightened coverage of industry perspectives could lead to a dampening of political will to act on climate (refs. 4, 5; cf. ref. 63). While business interests are not unanimous in opposing action to address climate change (64), some industry groups have mobilized powerfully against climate action (65–67). Meanwhile, businesses supportive of climate action tend to translate climate politics into “business as usual” and suggest that the problem can be solved within existing organizational routines (68) and socioeconomic arrangements (69, 70). This suggests that media portrayals that provide visibility to business interests’ perspectives may be unlikely to promote public concern and political mobilization over climate change.

More broadly, this finding is significant because it supports claims that business interests have disproportionate sway in shaping policy debates in contemporary American democracy (8, 10, 12). In particular, it is consistent with the idea that businesses and industries that are perceived as important for macroeconomic functioning can wield influence implicitly because politicians, social movements, media professional, and other decision makers take their views and reactions into account when crafting and debating public policy (11, 34, 42, 43, 45). In contrast, I find little support for the idea that business interests gain influence through baldly leveraging their economic resources, as the amount of financial resources that an organization has at its disposal does not significantly predict the visibility of their climate messages. While this form of business power may influence policy outcomes through other mechanisms or in other cases, I find no evidence of it influencing whose messages receive media coverage in the climate change debate.

In addition, my findings suggest that journalists continue to provide “false balance” on the issue of climate change (18), despite some scholars’ claims that this practice is a thing of the past. This is significant for climate change communications because it suggests that journalistic norms of balance and objectivity continue to provide a distorted picture of elite opinion on climate change. However, it is important to note that these findings are not incompatible with other research suggesting that the shape that the balance norm has taken in recent years may be shifting (27). For example, some have claimed that journalists now give less visibility to the views of contrarian scientists in particular (26, 71), while others have noted that journalists now provide contextual information characterizing contrarian voices as outside the mainstream (25). Because I examine all arguments opposing climate action—regardless of whether or not these arguments justify inaction through rejection of the scientific basis of climate change or some other reason—it is possible that messages opposing climate action have changed form, such that rejection of climate science per se has become less common, and action is opposed for some other reason. However, my findings run counter to the conclusion that the balance norm is no longer relevant to climate change reporting. On the contrary, my research suggests that the balance norm continues to operate, with messages opposing climate action receiving media visibility out of proportion to their marginal position among the messages organizations produce about climate change.

Despite these advances, the current research has limitations that open up possibilities for further inquiry. First, I focus here on how successful organizations’ messages are in entering mainstream media as a proxy for organizational influence in policy debates, while leaving unexamined other mechanisms through which organizations may attempt to achieve their political goals. For example, some organizations might choose to pursue an “insider” path to policy influence, bypassing attempts to influence public opinion while cultivating relationships directly with policy makers (72). Such insider strategies are not incompatible with attempts to influence public opinion through such tactics as policy framing and media visibility, and many interest groups use both types of strategies to attempt to achieve their aims (73). However, I focus here only on organizations’ attempts to influence public discourse, and so, my results cannot speak to other routes to interest group influence.

In addition, my use of observational data presents challenges in terms of causal inference. While the size and representativeness of my sample should lead to confidence that the trends I present here are robust, the causal interpretations I suggest should be taken as necessarily speculative. For example, I have argued based on previous scholarship that messages opposing climate action are afforded increased media visibility because journalistic norms of balance and objectivity lead journalists to overrepresent a minority viewpoint. However, other interpretations of this pattern are possible. For instance, conservative organizations may be more likely to use emotionally charged or culturally resonant language that journalists may deem more likely to engage readers (15, 74), leading messages that espouse conservative viewpoints on climate change to be overrepresented. Because my analysis includes limited information on the content of organizations’ messages, I cannot rule out this plausible alternative explanation. Future work should examine more deeply how the public debate around climate change is shaped by both the meanings of climate messages and the power relationships of the organizations that promote them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank Heather Haveman for her guidance on this project. In addition, I thank Robert Brulle; Neil Fligstein; Dan Hirschman; Ann Keller; Emily Rauscher; J. Timmons Roberts; Mark Suchman; Ann Swidler; Robb Willer; participants in the University of California, Berkeley Culture, Organizations, and Politics Workshop; participants in the Brown Work, Organizations, and Economy Workshop; and anonymous reviewers for invaluable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. Finally, I thank Rui Ju and Isabel Shaw for their skilled assistance in several phases of the research process.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The database of press releases and Stata code for replicating the analyses have been deposited in the openICPSR Repository (accession no. 116561).

*By “contrarian scientists,” I mean the small number of natural scientists who dispute the occurrence, seriousness, and/or anthropogenic causes of global warming.

†However, it is possible that this effect will disappear after the mid-2000s or will depend on the ideology of the news source. I assess these possibilities empirically below.

‡To construct the sample, I search the database of PR Newswire, the largest national distributor of press releases, using the terms “climate change,” “global warming,” “greenhouse effect,” and “greenhouse gas/gases/gasses.” I then take a 20% systematic sample of all press releases for most years in the study period, with oversampling of years in which many fewer press releases were released. More details on sample construction are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

§I conceptualize “opposition to climate action” as including both 1) statements that deny the reality, anthropogenic causes, and/or seriousness of climate change and 2) statements that argue we should not take action to address climate change, regardless of their position on the underlying science. This definition therefore includes both 1) epistemic skepticism and 2) response skepticism in Capstick and Pidgeon’s (75) terms. More details on coding procedures and reliability checks are in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods.

¶These additional analyses can be reproduced using the data and Stata code deposited online (openICPSR Repository accession no. 116561).

#The opposite relationship between media visibility and organizational misrepresentation could also exist. That is, messages where a company misrepresents itself as supportive of climate action might be particularly successful in receiving media attention because these companies’ support is seen as surprising and hence, newsworthy (64, 63). However, this would, if anything, lead me to underestimate the degree to which interests opposed to climate action have received disproportionate visibility in the climate change debate and so, does not constitute a threat to the validity of my findings.

‖While the magnitude of the coefficient is larger among businesses, the effect appears more reliable among civil society organizations. In addition, the interactive model suggests that the difference in size of the coefficients is not statistically significant.

**Another potential concern is that statements made in press releases may not be identical in tone or political valence to that of the press release as a whole, so the individual statements that are picked up in newspapers need not match my coding of press release message characteristics. However, as shown in SI Appendix, Table S6, the vast majority of statements cited in the newspapers I studied are similar in overall meaning to the press releases from which they originate (195 of 207 total statements or 94.2%). This supports the validity of my analysis using the overall press release coding, which is necessary to compare press releases that are successful in gaining media attention with those that are not.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1921526117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boykoff M. T., Roberts J. T., “Media coverage of climate change: Current trends, strengths, weaknesses” in Human Development Reports 2007/8, (United Nations Development Programme, New York, NY, 2007), pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulme M., Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity, (Cambridge University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewandowsky S., Gignac G. E., Vaughan S., The pivotal role of perceived scientific consensus in acceptance of science. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 399–404 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brulle R. J., Carmichael J., Jenkins J. C., Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the US, 2002–2010. Clim. Change 114, 169–188 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael J. T., Brulle R. J., Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: An integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Env. Polit. 26, 232–252 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boussalis C., Coan T. G., Text-mining the signals of climate change doubt. Glob. Environ. Change 36, 89–100 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCright A. M., Dunlap R. E., Defeating Kyoto: The conservative movement’s impact on US climate change policy. Soc. Probl. 50, 348–373 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartels L. M., Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age, (Princeton University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahl R. A., Who Governs?: Democracy and Power in an American City, (Yale University Press, 1961). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs L. R., Skocpol T., Inequality and American Democracy: What We Know and What We Need to Learn, (Russell Sage Foundation, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindblom C. E., Politics and Markets: The World’s Political-Economic Systems, (Basic Books, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacker J. S., Pierson P., Business power and social policy: Employers and the formation of the American welfare state. Polit. Soc. 30, 277–325 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freudenburg W. R., Privileged access, privileged accounts: Toward a socially structured theory of resources and discourses. Soc. Forces 84, 89–114 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wetts R., Whose messages make the news on climate? openICPSR Repository. https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/116561/version/V1/view. Deposited 13 May 2020.

- 15.Bail C. A., Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream, (Princeton University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigall-Brown C., What gets covered? An examination of media coverage of the environmental movement in Canada. Can. Rev. Sociol. 53, 72–93 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antilla L., Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 15, 338–352 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boykoff M. T., Boykoff J. M., Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press. Glob. Environ. Change 14, 125–136 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Painter J., Ashe T., Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007–10. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 44005 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boykoff M. T., Lost in translation? United States television news coverage of anthropogenic climate change, 1995–2004. Clim. Change 86, 1–11 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen A., Communication, media and environment: Towards reconnecting research on the production, content and social implications of environmental communication. Int. Commun. Gaz. 73, 7–25 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oreskes N., Beyond the ivory tower. The scientific consensus on climate change. Science 306, 1686 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho A., Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: Re-reading news on climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 16, 223–243 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen A. M., Vincent E. M., Westerling A. L., Discrepancy in scientific authority and media visibility of climate change scientists and contrarians. Nat. Commun. 10, 3502 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brüggemann M., Engesser S., Beyond false balance: How interpretive journalism shapes media coverage of climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 58–67 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiles S. S., Hinnant A., Climate change in the newsroom: Journalists’ evolving standards of objectivity when covering global warming. Sci. Commun. 36, 428–453 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmid-Petri H., Adam S., Schmucki I., Häussler T., A changing climate of skepticism: The factors shaping climate change coverage in the US press. Public Underst. Sci. 26, 498–513 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsasser S. W., Dunlap R. E., Leading voices in the denier choir: Conservative columnists’ dismissal of global warming and denigration of climate science. Am. Behav. Sci. 57, 754–776 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman L., Maibach E. W., Roser-Renouf C., Leiserowitz A., Climate on cable: The nature and impact of global warming coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC. Int. J. Press. 17, 3–31 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman L., Hart P. S., Milosevic T., Polarizing news? Representations of threat and efficacy in leading US newspapers’ coverage of climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 26, 481–497 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell S., Institutional influences on business power: How “privileged” is the business council of Australia? J. Public Aff. Int. J. 6, 156–167 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs D., Business Power in Global Governance, (Lynne Rienner, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy D. L., Egan D., Capital contests: National and transnational channels of corporate influence on the climate change negotiations. Polit. Soc. 26, 337–361 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrow C., Pulver S., “Organizations and markets” in Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives, Dunlap R. E., Brulle R. J., Eds. (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2015), pp. 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beder S., Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism, (Green Books, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domhoff G. W., Who Rules America?: The Triumph of the Corporate Rich, (McGraw-Hill, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis J., Williams A., Franklin B., A compromised fourth estate? UK news journalism, public relations and news sources. Jpn. Stud. 9, 1–20 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miliband R., The State in Capitalist Society, (Basic Books, 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills C. W., The Power Elite, (Oxford University Press, 1956). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeffer J., Salancik G. R., The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective, (Harper and Row, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrell J., Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 92–97 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrews K. T., Caren N., Making the news: Movement organizations, media attention, and the public agenda. Am. Sociol. Rev. 75, 841–866 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Block F., Revising State Theory: Essays in Politics and Postindustrialism, (Temple University Press, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnaiberg A., Gould K. A., Environment and Society: The Enduring Conflict, (Blackburn Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnaiberg A., The political economy of environmental problems and policies: Consciousness, conflict, and control capacity. Adv. Hum. Ecol. 3, 23–64 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Offe C., Wiesenthal H., Two logics of collective action: Theoretical notes on social class and organizational form. Polit. Power Soc. Theory 1, 67–115 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meckling J., The globalization of carbon trading: Transnational business coalitions in climate politics. Glob. Environ. Polit. 11, 26–50 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuchs D., Commanding heights? The strength and fragility of business power in global politics. Millennium 33, 771–801 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hajer M. A., The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process, (Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davidson D. J., Private property wrongs: Uncovering the contradictory articulations of an hegemonic ideology. Sociol. Inq. 77, 104–125 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson D. J., Dunlap R. E., Introduction: Building on the legacy contributions of William R. Freudenburg in environmental studies and sociology. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2, 1–6 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenberg P., Disproportionality and resource-based environmental inequality: An analysis of neighborhood proximity to coal impoundments in Appalachia. Rural Sociol. 82, 149–178 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller Gaither B., Gaither T. K., Marketplace advocacy by the US fossil fuel industries: Issues of representation and environmental discourse. Mass Commun. Soc. 19, 585–603 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carragee K. M., Roefs W., The neglect of power in recent framing research. J. Commun. 54, 214–233 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vliegenthart R., Van Zoonen L., Power to the frame: Bringing sociology back to frame analysis. Eur. J. Commun. 26, 101–115 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis G. F., Cobb J. A., Resource dependence theory: Past and future. Res. Sociol. Organ. 28, 21–42 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fligstein N., The Architecture of Markets: An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century Capitalist Societies, (Princeton University Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haveman H. A., Wetts R., Contemporary organizational theory: The demographic, relational, and cultural perspectives. Sociol. Compass 13, e12664 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katila R., Rosenberger J. D., Eisenhardt K. M., Swimming with sharks: Technology ventures, defense mechanisms and corporate relationships. Adm. Sci. Q. 53, 295–332 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delmas M. A., Burbano V. C., The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manage. Rev. 54, 64–87 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grumbach J. M., Polluting industries as climate protagonists: Cap and trade and the problem of business preferences. Bus. Polit. 17, 633–659 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramus C. A., Montiel I., When are corporate environmental policies a form of greenwashing? Bus. Soc. 44, 377–414 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoffman A. J., How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate, (Stanford University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carpenter C., Businesses, green groups and the media: The role of non-governmental organizations in the climate change debate. Int. Aff. 77, 313–328 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brulle R. J., Networks of opposition: A structural analysis of US climate change countermovement coalitions 1989–2015. Sociol. Inq. (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fisher D. R., Bringing the material back in: Understanding the US position on climate change. Sociol. Forum 21, 467–494 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Skocpol T., Hertel-Fernandez A., The Koch network and republican party extremism. Perspect. Polit. 14, 681–699 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright C., Nyberg D., An inconvenient truth: How organizations translate climate change into business as usual. Acad. Manage. J. 60, 1633–1661 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swyngedouw E., Apocalypse forever? Theory Cult. Soc. 27, 213–232 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wetts R., Models and morals: Elite-oriented and value-neutral discourse dominates American organizations’ framings of climate change. Soc. Forces 98, 1339–1369 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boykoff M. T., Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006. Area 39, 470–481 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grant W., Insider Groups, Outsider Groups, and Interest Group Strategies in Britain, (University of Warwick, Department of Politics, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Binderkrantz A., Interest group strategies: Navigating between privileged access and strategies of pressure. Polit. Stud. 53, 694–715 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Snow D. A., Rochford E. B. Jr., Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 51, 464–481 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Capstick S. B., Pidgeon N. F., What is climate change scepticism? Examination of the concept using a mixed methods study of the UK public. Glob. Environ. Change 24, 389–401 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.