Abstract

DNA:RNA hybrids constitute a well-known source of recombinogenic DNA damage. The current literature is in agreement with DNA:RNA hybrids being produced co-transcriptionally by the invasion of the nascent RNA molecule produced in cis with its DNA template. However, it has also been suggested that recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids could be facilitated by the invasion of RNA molecules produced in trans in a Rad51-mediated reaction. Here, we tested the possibility that such DNA:RNA hybrids constitute a source of recombinogenic DNA damage taking advantage of Rad51-independent single-strand annealing (SSA) assays in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. For this, we used new constructs designed to induce expression of mRNA transcripts in trans with respect to the SSA system. We show that unscheduled and recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids that trigger the SSA event are formed in cis during transcription and in a Rad51-independent manner. We found no evidence that such hybrids form in trans and in a Rad51-dependent manner.

Research organism: S. cerevisiae

Introduction

R loops are structures formed by a DNA:RNA hybrid and the complementary displaced single stranded DNA (ssDNA). They were observed naturally as programmed events in specific genomic sites such as the S regions of Immunoglobulin genes in mammals or mitochondrial DNA (Chang et al., 1985; García-Muse and Aguilera, 2019; Yu et al., 2003), where they play specific functions by promoting class switch recombination or DNA replication, respectively; but also as unscheduled non-programmed structures upon dysfunction of RNA binding proteins involved in the assembly or processing and export of the protein-mRNA particle (mRNP) such as the THO complex or the SRSF1 splicing factor (Huertas and Aguilera, 2003; Li and Manley, 2005). Also, they have been inferred in the rDNA regions of the bacterial chromosome upon Topo I inactivation (Drolet et al., 1995). Accumulated evidence indicates that R loops are detected from yeast to humans in many transcribed regions of the eukaryotic genome in wild-type cells, in cells defective in several metabolic processes covering from RNA processing to DNA replication and repair and in cells deficient in specific chromatin factors (Bhatia et al., 2014; García-Muse and Aguilera, 2019; García-Rubio et al., 2015; Herrera-Moyano et al., 2014; Mischo et al., 2011; Paulsen et al., 2009; Schwab et al., 2015). The biological consequences of such R loop structures are diverse and include replication stress, DNA breaks and genome instability that can be detected as hyperrecombination, plasmid loss or gross chromosomal rearrangements (García-Muse and Aguilera, 2019). Indeed, DNA:RNA hybrids have been inferred by their potential to induce DNA damage and recombination, but they can also be directly detected via different methodologies. These include electrophoresis detection after nuclease treatment, bisulfite mutagenesis or either in situ immunofluorescence or DNA:RNA Immuno-Precipitation (DRIP) using the S9.6 anti-DNA:RNA monoclonal antibody (García-Muse and Aguilera, 2019).

The increasing number of reports showing R loop accumulation in different organisms from bacteria to human cells, and the relevance of their functional consequences, whether on genome integrity, chromatin structure and gene expression suggest that most DNA:RNA hybrids are compatible with a co-transcriptional formation (García-Muse and Aguilera, 2019). This is consistent with the idea that it is the RNA produced in cis the one that invades the duplex DNA, a reaction that can be facilitated by DNA sequence and supercoiling (Stolz et al., 2019) as well as by nicking of the DNA template (Roy et al., 2010). The evidence of DNA:RNA hybrid formation at breaks has matured in the last years (Cohen et al., 2018; D'Alessandro et al., 2018; Li et al., 2016; Ohle et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2018; Yasuhara et al., 2018) although the source and role of such hybrids remains still controversial (Aguilera and Gómez-González, 2017; Puget et al., 2019). Of note, genome-wide mapping results have been interpreted in diverse manners by different labs. Whereas some claim that DNA:RNA hybrids detected around DNA breaks mostly accumulate at transcribing sites (Cohen et al., 2018), in agreement with their co-transcriptional formation, others suggest that there is no preference for DNA:RNA hybrids to form at transcribed loci in human cells (D'Alessandro et al., 2018), implying a scenario in which DNA:RNA hybrids at break sites would form either de novo or with RNAs produced at different loci (in trans). Moreover, it has been shown in yeast that short RNAs can be used as templates for the recombinational repair of DSBs in a reaction catalyzed by Rad52 (Keskin et al., 2014).

DNA:RNA hybrids can also form in vitro with the aid of the bacterial DNA strand exchange protein RecA (Kasahara et al., 2000; Zaitsev and Kowalczykowski, 2000). In vivo, DNA:RNA hybrids are formed with RNAs produced in trans as intermediates in the course of ribonucleoprotein-mediated reactions such as telomerase and CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein involved in specific reactions (Collins, 2000; Jinek et al., 2012). They have also been reported to have regulatory roles in gene expression when formed by long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) at in trans loci such as the cases of the GAL lncRNA in yeast (Cloutier et al., 2016) or the APOLO lncRNA in plants (Ariel et al., 2020). In summary, despite the accumulating evidence that in vivo DNA:RNA hybrids formed in cis constitute a threat for genome stability, an open question is whether DNA:RNA hybrids also form in trans as a potential source of recombinogenic DNA damage. To our knowledge, this has only been addressed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Wahba et al., 2013). By S9.6 immunofluorescence (IF) and a yeast artificial chromosome-based genetic assay that measures gross chromosomal rearrangements, it was inferred that DNA:RNA hybrids could be formed with RNAs produced in trans by a reaction catalyzed by the eukaryotic DNA strand exchange protein Rad51 (Wahba et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the fact that the detected gross chromosomal rearrangements could depend on Rad51 and that the S9.6 antibody can also recognize dsRNAs (Hartono et al., 2018; König et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2018), prompted us to address this question using a different approach. Using Rad51-independent recombination assays in which the initiation region could be unambiguously delimited, we do not find evidence for recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids forming in trans. Instead, we provide genetic evidence that DNA:RNA hybrids compromising genome integrity are formed in cis and in a Rad51-independent manner.

Results

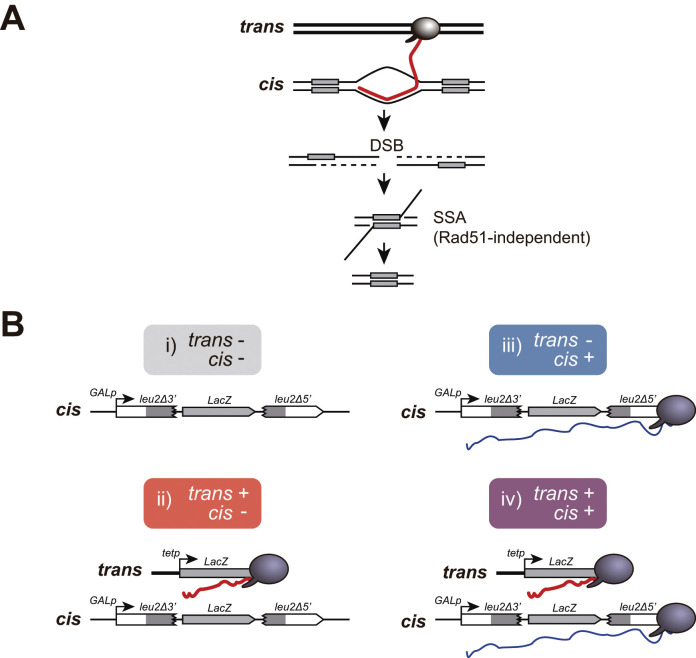

A new genetic assay to detect recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids with RNA produced in trans

We developed a new genetic assay to infer the formation of recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids with RNAs produced in trans. It is based on two plasmids, one containing the recombination system and the LacZ gene in cis (GL-LacZ recombination system), and another one providing the in trans LacZ transcripts (tetp:LacZ) (Figure 1). The bacterial LacZ gene consists of a 3 Kb sequence with high G+C content previously reported to be hyper-recombinant and difficult to transcribe in DNA:RNA hybrid-accumulating strains, such as tho mutants (Chávez et al., 2001).

Figure 1. A new genetic assay to detect recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids in trans.

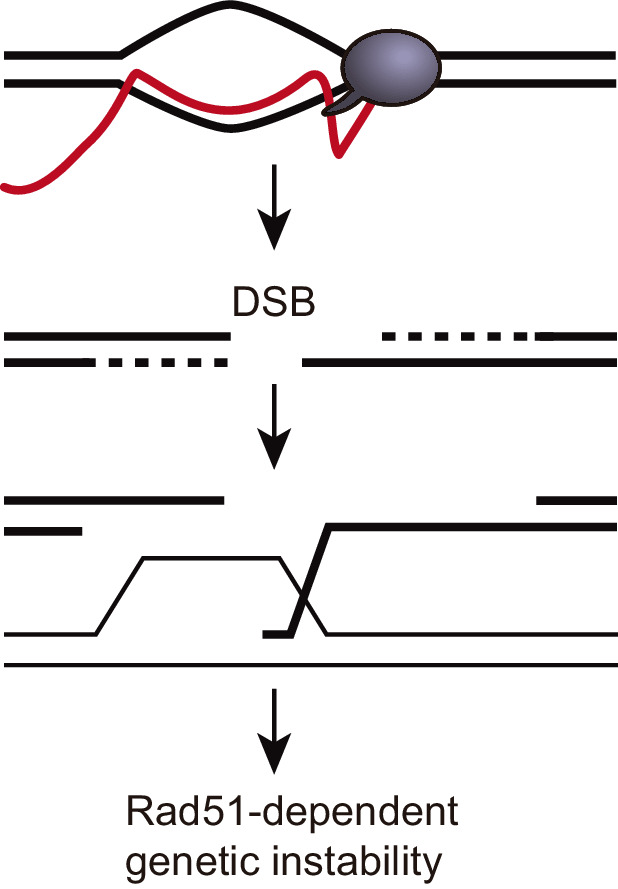

(A) DSBs induced in between direct repeats by DNA:RNA hybrids putatively formed with RNA produced in trans would be repaired by Rad51-independent Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) causing the deletion of one of the repeats. A DSB is depicted for simplicity, but other recombinogenic lesions such as nicks or ssDNA gaps cannot be ruled out. (B) Schematic representation of the recombination assay to study the recombinogenic potential RNA produced by transcription (Trx) in cis or in trans. Four combinations were studied: i) no transcription, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (2% glucose) and an empty plasmid; ii) transcription in trans, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (2% glucose) and the tetp:LacZ construct; iii) transcription in cis, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on (2% galactose) and an empty plasmid; and iv) transcription in cis and in trans, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on (2% galactose) and the tetp:LacZ construct.

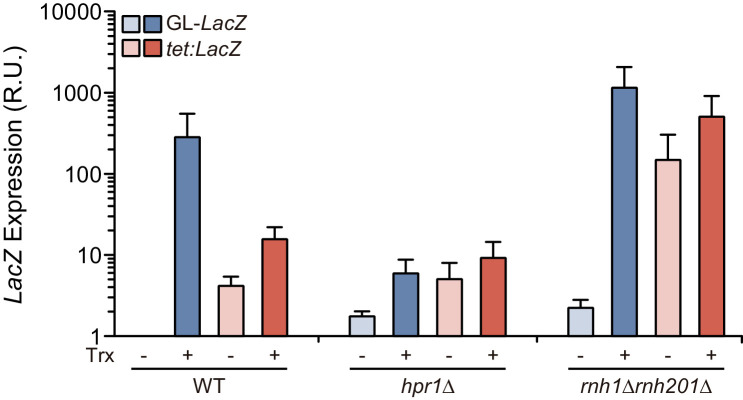

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. LacZ expression levels in the GL-LacZ and tetp:LacZ constructs.

The GL-LacZ recombination system is a leu2 direct-repeat construct carrying the LacZ gene in between and under the GAL1 inducible promoter so that this construct is transcribed as a single RNA unit driven from the GAL1 promoter (Piruat and Aguilera, 1998). Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) events cause the deletion of the LacZ sequence and one of the leu2 repeats leading to Leu+ recombinants in a Rad51-independent manner (Figure 1A). To provide LacZ transcripts in trans, we used a fusion construct containing the complete bacterial LacZ gene sequence under the doxycycline-inducible tet promoter (tetp:LacZ). As a control of no expression in trans, we used transformants with an empty plasmid to avoid any possible effect from leaky transcription from the tet promoter in the presence of doxycycline.

Yeast strains carrying both GL-LacZ recombination system and the tetp:LacZ construct were used to assay SSA events in the four different possible conditions: i) no transcription, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (2% glucose) and an empty plasmid; ii) transcription in trans, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (2% glucose) and the tetp:LacZ construct; iii) transcription in cis, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on (2% galactose) and an empty plasmid; and iv) transcription in cis and in trans, with GL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on (2% galactose) and the tetp:LacZ construct (Figure 1B).

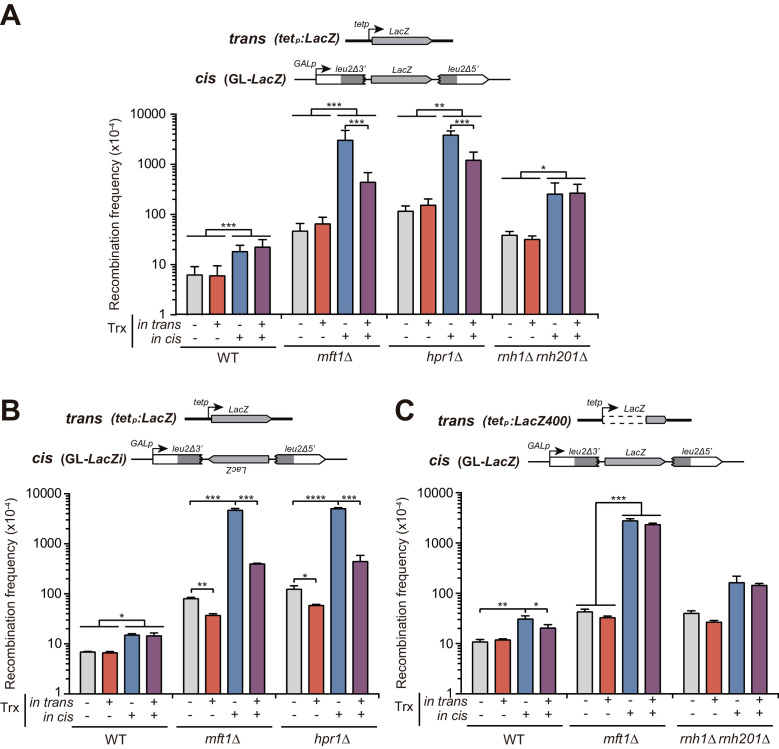

RNAs produced in trans are not a spontaneous source of recombinogenic DNA damage

The analysis of recombination in wild-type cells revealed that whereas the stimulation of transcription in cis elevated the frequency of recombination threefold, the stimulation of transcription in trans driven from the tetp:LacZ construct had no effect on recombination (Figure 2A). These results already suggest that homologous transcripts coming from a different locus do not represent a detectable source of genetic instability in wild-type conditions and thus argue against the hypothesis that spontaneous DNA:RNA hybrids could be formed with mRNAs generated in trans. However, it is known that mRNA coating protects DNA from co-transcriptional RNA hybridization. Thus, we wondered if transcripts produced in trans could induce recombination in mRNP-defective mutants such as those of the THO complex. Hence, we performed our experiments in mft1∆ and hpr1∆ mutant strains. mft1∆ and hpr1∆ enhanced recombination slightly when transcription in cis was switched off (Figure 2A), likely as a consequence of leaky transcription form the GAL1 promoter in glucose (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). More significantly and in agreement with previous reports (Chávez et al., 2000), recombination frequencies rocketed when transcription was stimulated in cis. However, transcription activation in trans did not enhance recombination, as it would be expected if additional DNA:RNA hybrids could form with RNA produced in trans.

Figure 2. Analysis of the effect on genetic recombination of RNA produced in cis or in trans.

(A) Recombination analysis in WT (W303), rnh1Δ rnh201Δ (HRN2.10C), mft1Δ (WMK.1A) and hpr1Δ (U678.4C) strains carrying GL-LacZ plasmid system (pRS314-GL-LacZ) plus either the pCM190 empty vector or the same vector carrying the LacZ gene (pCM179). (B) Recombination analysis in WT (W303), mft1Δ (WMK.1A) and hpr1Δ (U678.4C) strains carrying GL-LacZi plasmid plus either the pCM190 empty vector or the same vector carrying the sequence of the LacZ gene (pCM179). (C) Recombination analysis in WT (W303), rnh1Δ rnh201Δ (HRN2.10C) and mft1Δ (WMK.1A) strains carrying GL-LacZ plasmid system (pRS314-GL-LacZ) plus either the pCM190 empty vector or the same vector carrying the last 400 bp from the 3’ end of the LacZ gene (pCM190:LacZ400). In all panels, average and SEM of at least three independent experiments consisting in the median value of six independent colonies each are shown. *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

Instead, under conditions of high transcription of the recombination system (transcription in cis), RNA driven from an ectopic locus (transcription in trans) led to a partial suppression of the hyper-recombination. The reason for such suppression might involve the potential ability of the remotely produced RNAs to interfere with transcription occurring at the GL-LacZ construct. Given that a DNA:RNA hybrid produced in the template DNA strand can impair transcription elongation (Tous and Aguilera, 2007), one possibility would be that this interference is mediated by DNA:RNA hybrids formed between the RNA produced in trans and the transcribed DNA strand of the GL-LacZ construct. To rule out this possibility, we used an alternative recombination system (GL-LacZi), in which the LacZ sequence was inverted so that the LacZ transcript produced in trans would not be able to anneal with the transcribed DNA strand of the GL-LacZi system (Figure 2B). We detected a strong hyper-recombination in hpr1∆ cells when the LacZ sequence was transcribed in agreement with previous reports and with the fact that it has been shown that it is the length (and the GC content) but not the orientation of the lacZ sequence what impairs transcription and triggers hyper-recombination (Chávez and Aguilera, 1997; Chávez et al., 2001). Surprisingly, the production of RNAs in trans from the tet::LacZ construct also led to a reduction of the hyper-recombination in this system. Furthermore, in this case, the suppression was stronger and was also observed in glucose, when transcription in cis was off. This could be explained because, in this scenario, the RNA produced in trans is complementary to the mRNA produced in cis. Consequently, they can hybridize together forming a dsRNA that would preclude the possibility to form DNA:RNA hybrids at the GL-LacZi construct.

Since transcription from the long LacZ gene is inefficient and leads to unstable RNA products, particularly in tho mutants (Chávez et al., 2001), we made a new construct with only the last 400 bp of LacZ (tetp:LacZ400) (Figure 2C). Strikingly, in this case, we observed no suppression of the tho-induced hyper-recombination by the production of RNA in trans. More importantly and again, recombination frequencies were not significantly enhanced by transcription in trans in any of the strains or conditions tested, further arguing against mRNA produced in trans as a possible source of recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids.

The THO complex is thought to prevent R-loops mainly by promoting a proper mRNA-protein assembly (Luna et al., 2019), whereas the two RNase H enzymes efficiently degrade the RNA moiety of DNA:RNA hybrids once formed (Cerritelli and Crouch, 2009). Thus, to favor DNA:RNA hybrid accumulation, we used cells lacking both RNases H1 and H2 and we determined the impact on SSA. Figure 2A and C show that rnh1∆ rnh201∆ cells elevated the recombination frequency when transcription was stimulated in cis, as expected. Importantly, the recombination frequencies were not altered by producing transcripts in trans, arguing again against the recombinogenic potential of putative DNA:RNA hybrids formed with RNAs produced in trans.

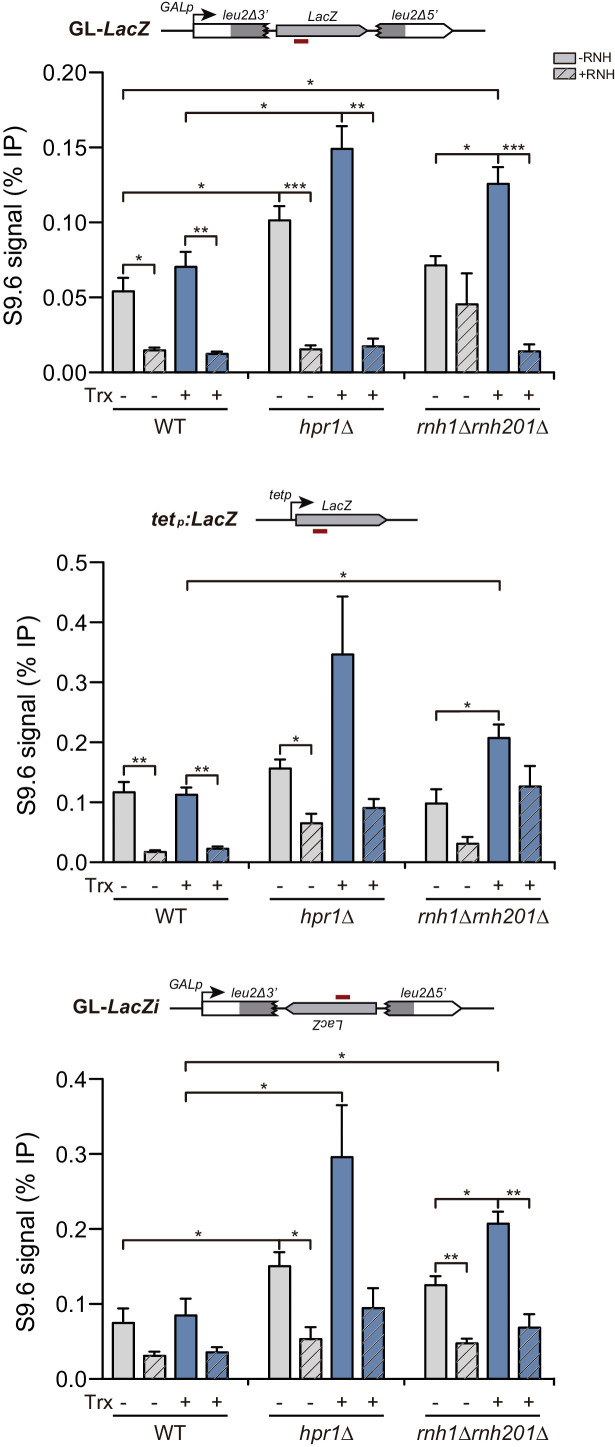

In order to confirm DNA:RNA hybrid formation in these different sequence contexts, we performed DRIP experiments at the LacZ sequence (Figure 3) and we observed that DNA:RNA hybrids accumulate in both, hpr1∆ and rnh1∆ rnh201∆ mutants, and in all GL-LacZ, tet:LacZ and GL:lacZi sequences as expected, despite the technical difficulty of detecting increases in hybrid accumulation in plasmids, since they cause plasmid loss.

Figure 3. Detection of co-transcriptional DNA:RNA hybrids in hpr1Δ and rnh1Δ rnh201Δ mutants at the LacZ-containing constructs under the GAL1 or tet promoters.

DNA:RNA Immuno-Precipitation (DRIP) with the S9.6 antibody in WT (W303), hpr1Δ (U678.4C) and rnh1Δ rnh201Δ (HRN2.10C) strains in asynchronous cultures treated or not in vitro with RNase H in the GL-LacZ, tetp:LacZ and GL-LacZi constructs turned transcriptionally off (2% glucose or 5 μg/mL doxycycline) or on (2% galactose and in the absence of doxycycline). Average and SEM of three independent experiments are shown *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

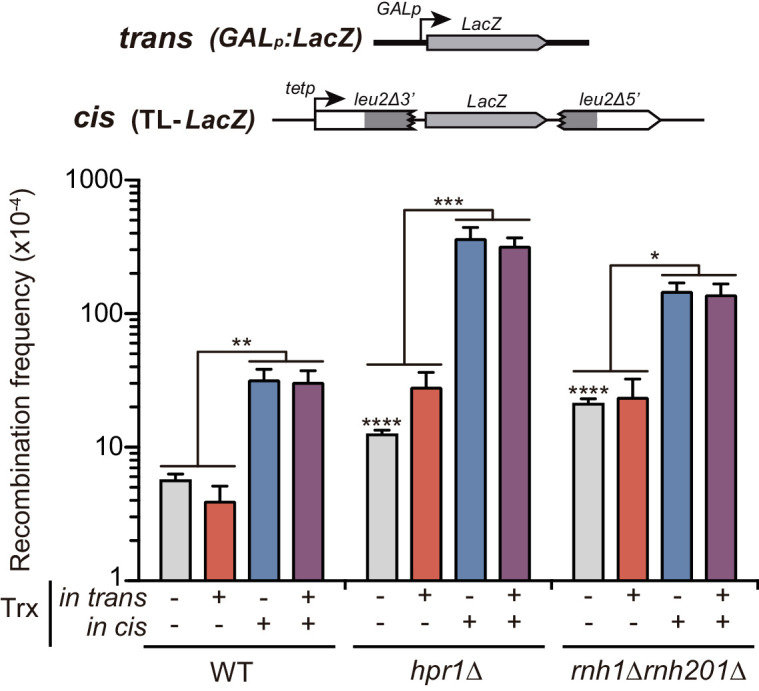

Given that the levels of transcription from the GAL1 and tet promoters used for the constructs are very different (Figure 1—figure supplement 1), we decided to perform recombination tests with similar constructs in which the promoters were interchanged. Thus, we studied recombination in the TL-LacZ recombination system (Santos-Pereira et al., 2013) and used a GAL:LacZ construct to produce the LacZ transcripts from a remote locus. Figure 4 shows that, whereas transcription at the TL-LacZ recombination system enhanced recombination as previously published (Santos-Pereira et al., 2013), again no significant stimulation of recombination was detected when RNAs were produced in trans in either wild-type, hpr1∆ or rnh1∆ rnh201∆ cells even when the RNA was generated from the strong GAL1 promoter.

Figure 4. Analysis of the effect on genetic recombination of RNA produced in cis or in trans with different promoters.

Recombination analysis in WT (W303), hpr1Δ (U678.4C) and rnh1Δ rnh201Δ (HRN2.10C) carrying TL-LacZ plasmid system (pCM184-TL-LacZ) plus either the pRS416 empty vector or the same vector carrying the LacZ gene (pRS416-GALLacZ). In this case, the four combinations studied were: i) no transcription, with TL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (5 μg/mL doxycycline) and an empty plasmid; ii) transcription in trans, with TL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally off (5 μg/mL doxycycline) and the GAL-LacZ construct switched on (2% galactose); iii) transcription in cis, with TL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on and an empty plasmid; and iv) transcription in cis and in trans, with TL-LacZ construct turned transcriptionally on and the GAL-LacZ construct switched on (2% galactose). Average and SEM of at least three independent experiments consisting in the median value of six independent colonies each are shown. *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

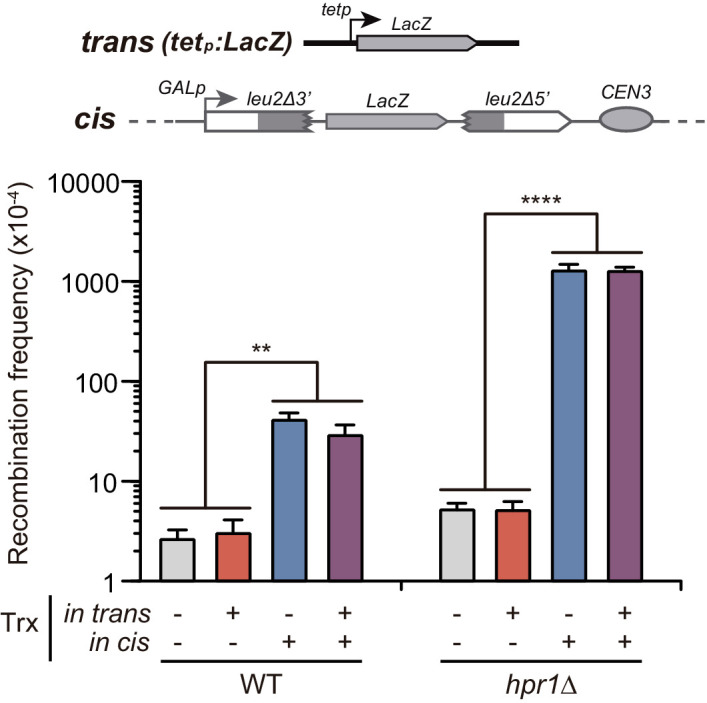

Finally, since all experiments were performed in plasmid-born systems in the original W303 background bearing the rad5-G535R mutation (Fan et al., 1996), we integrated the GL-LacZ system in the chromosome of a RAD5 wild-type strain to ascertain that the rad5-G535R mutation did not affect the results as well as to confirm that the results were the same in a chromosome locus. As it can be seen in Figure 5, transcription of the chromosomal recombination system promoted a 30-fold increase in recombination levels in the tho mutant hpr1∆ with respect to the WT, in agreement with all previous data showing that co-transcriptional DNA:RNA hybrids are a potent source of recombination. By contrast, mRNA produced at a different locus had no effect on recombination, neither in wild-type cells nor in the tho mutant hpr1∆. Hence, altogether, these results argue that, in contrast to mRNA produced in cis, RNA produced at a particular locus does not lead to recombinogenic DNA damage at regions located in trans.

Figure 5. Analysis of the effect on genetic recombination of RNA produced in trans of chromosome III.

Recombination analysis in WT (WGLZN), hpr1Δ (HGLZN) strains carrying the GL-LacZ recombination system integrated in chromosome III. Strains were transformed with empty vector pCM190 or the same vector carrying the LacZ gene (pCM179). Average and SEM of at least three independent experiments are shown consisting in the median value of six independent colonies each. **, p≤0.01; ****, p≤0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

Rad51 is not required for DNA:RNA hybridization

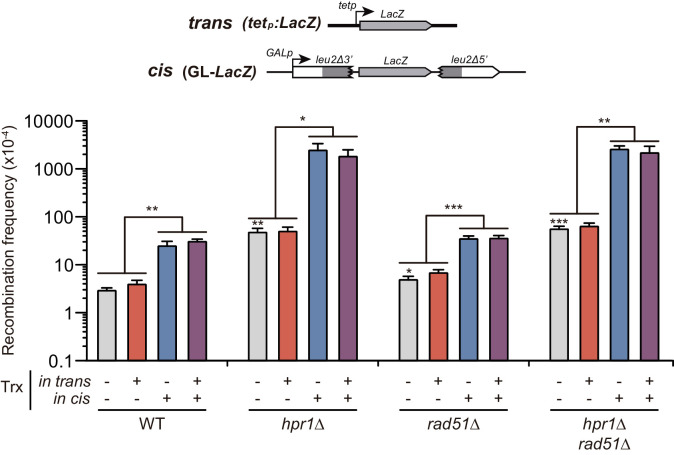

We next wondered about the possible role of the recombination protein Rad51 in DNA:RNA hybridization. To examine this, we analyzed in hpr1∆ cells the effect of transcribing the ectopic tet:LacZ construct on recombination in our direct-repeat systems when these were not transcribed (Figure 6). It is important to remark that the recombination events detected in our assays are deletions occurring by SSA between direct repeats, which do not require Rad51 (Pardo et al., 2009). Indeed, in agreement with SSA annealing being Rad51-independent, RAD51 deletion caused no significant changes in the recombination frequencies in our assay. Thus, any conclusion about Rad51-dependency or independency of the hybridization inferred from our assay is not contaminated by a possible direct role of Rad51 in the event we are studying. Importantly, we observed no differences when RAD51 was deleted in hpr1∆ cells even when the LacZ sequence was expressed from the plasmid containing the tet::LacZ construct. This result argues against Rad51 facilitating or impeding the formation of DNA:RNA hybrids with RNAs produced in trans.

Figure 6. Analysis of the effect on genetic recombination of RNA produced in trans with or without Rad51.

Recombination analysis in WT (W303), hpr1Δ (U678.1C), rad51Δ (WSR51.4A) and hpr1Δ rad51Δ (HPR51.15A) strains carrying GL-LacZ plasmid system (pRS314-GL-LacZ) plus either the pCM190 empty vector or the same vector carrying the LacZ gene (pCM179). Average and SEM of at least three independent experiments consisting in the median value of six independent colonies each are shown. *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01, ***, p≤0.001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

We then wondered whether the formation of known recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids formed in cis, such as those reported in the hpr1∆ mutant, requires Rad51. For this purpose, we studied the effect in the strong hyper-recombination phenotype of hpr1∆ when transcription was induced in cis. As shown in Figure 6, the absence of Rad51 had no effect on the hyper-recombination observed, as hpr1∆ rad51∆ cells elevated the recombination frequency more than 70-fold with respect to rad51∆, similarly to Rad51+ cells. This result clearly indicates that the in cis DNA:RNA hybrid-mediated hyper-recombination phenotype is actually independent on Rad51.

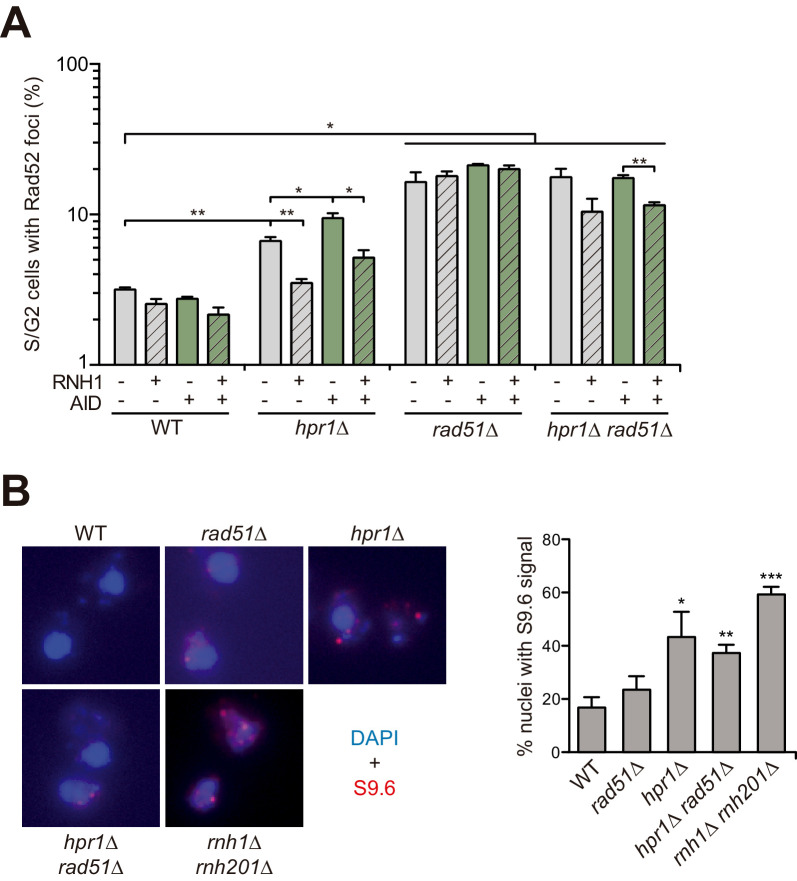

In parallel, we studied the formation of Rad52 foci, a marker of recombinogenic DNA breaks (Lisby et al., 2001), in which case we used AID overexpression to enhance the recombinogenic potential of R loops (Gómez-González and Aguilera, 2007) and RNase H overexpression to remove DNA:RNA hybrids (Figure 7A). In agreement with the role of the THO complex in R loop prevention, hpr1∆ caused an increase in Rad52 foci that was enhanced by AID overexpression and suppressed by RNase H overexpression, as previously reported (Alvaro et al., 2007; García-Pichardo et al., 2017; Wellinger et al., 2006). By contrast, the accumulation of Rad52 foci observed in rad51∆ cells was not affected by either AID or RNase H overexpression. This result argues that R loops are not the cause for the genetic instability observed in the absence of Rad51. The accumulation of Rad52 foci in rad51∆ cells is rather likely due to the accumulation of unrepaired recombination intermediates, as previously suggested (Alvaro et al., 2007). Importantly, hpr1∆ rad51∆ cells showed a similar result, further supporting that the accumulation of recombinogenic damage in hpr1∆ cells is independent on Rad51. Consequently, we next directly measured DNA:RNA hybrid accumulation by immunodetection with the S9.6 antibody on metaphase spreads. Figure 7B illustrates that the number of cells with S9.6 positive signal was similar in hpr1∆ and in hpr1∆ rad51∆ cells. Altogether, these results demonstrate that the Rad51 protein is not required for the DNA:RNA hybrid formation previously reported in THO mutants.

Figure 7. The increased genetic instability and DNA:RNA hybrids of hpr1∆ are independent on Rad51.

(A) Spontaneous Rad52-YFP foci formation in WT (W303), hpr1Δ (U678.1C), rad51Δ (WSR51.4A) and hpr1Δ rad51Δ (HPR51.15A) strains carrying the empty vectors pCM184 and pCM189, or a combination of both carrying the RNH1 or AID genes as indicated in the legend. (B) Representative images and value of the percent of the total nuclei scored that stained positively for DNA:RNA hybrids in chromatin spreads stained with the S9.6 antibody in WT (W303), hpr1Δ (U678.1C), rad51Δ (WSR51.4A), hpr1Δ rad51Δ (HPR51.15A) and RNH-R (rnh1Δ rnh201Δ) strains. In both panels, average and SEM of at least three independent experiments performed with more than 100 cells are shown. *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01, ***, p≤0.001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

Discussion

We have devised a new genetic assay to infer whether the source of DNA:RNA hybrids compromising genome integrity could potentially come from RNAs produced in trans. To reach this conclusion, we used an SSA assay. It is well established that SSA events are Rad51-independent; they do not require DNA strand exchange, but just annealing between resected single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) for which the action of Rad52 is sufficient (Figure 1A; Pardo et al., 2009). Our constructs show that, in contrast to the RNA produced at the site where SSA occurs, an RNA produced in a remote locus does not induce an increase in homology-directed repair. Importantly, recombination is not induced by in trans RNA production even when the major DNA:RNA removal machinery is absent (rnh1∆ rnh201∆ mutant) or when the RNA coating functions preventing DNA:RNA hybrid formation are impaired (tho mutants), arguing against the idea that harmful DNA:RNA hybrids could spontaneously form in trans and constitute a menace for genome integrity. Co-transcriptional R-loops are responsible for the hyper-recombination of hpr1∆ as reported previously (Huertas and Aguilera, 2003). Putative DNA:RNA hybrids formed in trans would be expected to further increase recombination levels. Instead, the simultaneous induction of transcription in cis and in trans (Figure 2A) reduced the strong hyper-recombinogenic effect of tho mutants. The fact that this suppressor effect was augmented when one of the LacZ sequences was inverted (Figure 2B) and prevented by a shorter LacZ construct (Figure 2C), which was reported to be more stable in tho mutant backgrounds (Chávez et al., 2001), suggests that the free RNA itself, and not in the form of DNA:RNA hybrids formed at the template DNA strand, plays some role in preventing the hyper-recombination, likely because stable RNAs can interfere with transcription at a homologous locus. However, no suppressor effect was observed when the recombination system was placed in a chromosome (Figure 5) or when the ectopic RNA was transcribed from the GAL1 promoter (Figures 2 and 4).

DNA:RNA hybrids formed with an RNA produced in trans were previously suggested to threaten genome integrity (Wahba et al., 2013). This conclusion was based on experiments performed with a yeast artificial chromosome after the induction of transcription of a homologous region placed at chromosome III. Recombination involving multiple substrates was first reported in S. cerevisiae, in which an induced-DSB triggered recombination between two other homologous fragments at different chromosomes (Ray et al., 1989). Tri-parental recombination assays have been successfully used since then to define specific features of the HR reaction as well as for studies of Break-Induced Recombination (BIR) or translocations and chromosomal rearrangements occurring between ectopic regions (Pardo and Aguilera, 2012; Piazza et al., 2017; Ruiz et al., 2009). However, such events are not the most adequate to infer recombination initiation unless this has been artificially induced (as is the case of an HO-induced DSB). Hence, the assay used to infer the potential of DNA:RNA hybrids formed with RNAs produced in trans to induce genetic instability (Wahba et al., 2013) relied on an RNA fragment produced at a (first) DNA region that could form a DNA:RNA hybrid with a (second) ectopic homologous DNA region that would promote its deletion or loss, leading to a genetically detectable phenotype. Thus, this assay does not exclude the possibility that the RNA forms the hybrid in cis inducing subsequently a DSB that would stimulate the recombination events studied (Figure 6). Indeed, this event would demand the action of Rad51 for DNA strand invasion, consistent with the results obtained (Wahba et al., 2013). Therefore, the increased genetic instability observed could be explained by the invasion of the 3’ end of a DNA break induced by the DNA:RNA hybrid formed at the first site (Figure 8) rather than implying that Rad51 is required for the RNA to invade the second DNA sequence.

Figure 8. A model to explain how DNA:RNA hybrids could induce Rad51-dependent genetic instability in trans.

DNA:RNA hybrid produced in cis can induce a DSB in the same sequence. The 3’ end of such a DSB could invade an ectopic homologous sequence and destabilize it. This DNA strand invasion event would require Rad51. In this model, genetic instability caused by hybrids in trans would be Rad51-dependent without the need of invoking a Rad51-mediated DNA:RNA hybrid formation in trans. A DSB is depicted for simplicity, but other recombinogenic lesions such as nicks or ssDNA gaps cannot be ruled out.

In our case, however, we show that the hyper-recombinogenic potential of DNA:RNA hybrids is Rad51-independent (Figure 4). Our assays involve two leu2 homologous repeats that recombine by Rad51-independent SSA. Indeed, as expected, RAD51 deletion caused no decrease in the observed recombination frequencies in our assay (Figure 5). Recombination between the leu2 repeats could be originated by either a DNA:RNA hybrid in cis or by a DSB occurring in between the repeats, or as suggested previously for tho mutants, by a bypass mechanism involving template switching (Gómez-González et al., 2009). It is worth noting that although we are depicting the SSA reactions as being initiated by a DSB (Figures 1 and 8), we cannot discard that the initial lesion triggered by a hybrid is a nick or ssDNA gap, as previously proposed for tho mutants (Gómez-González et al., 2009).

Similarly, a DSB occurring at the locus where the RNA in trans was generated could give rise to Leu+ recombinants in our assay. However, such recombination events would be Rad51-dependent, as they will require a Rad51-dependent invasion into the GL-LacZ construct (Figure 8). Hence, the Leu+ recombinants obtained in rad51∆ mutant cells (Figure 5) can only be explained by Rad51-independent events occurring in cis, at the GL-LacZ construct. Strikingly, the fact that we detected no significant increase in Leu+ recombinants by inducing transcription in trans, either in RAD51 or rad51∆ backgrounds rules out the possibility that recombinogenic DNA:RNA hybrids form in trans in our assay. It was previously shown that S9.6 signal detected by IF was reduced by rad51∆ in metaphase spreads (Wahba et al., 2013). By contrast, we detected S9.6 signal in metaphase spreads of the hpr1∆ mutant of the THO complex in both RAD51 and rad51∆ backgrounds (Figure 7B). The uncertainty about the identity of the structures detected by IF using the S9.6 antibody, which also recognizes dsRNA (Hartono et al., 2018; König et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2018), and the possibility that chromosomal spreads could preferentially visualize the rDNA regions, in which high levels of dsRNA structures formed by the rRNAs, makes difficult to make conclusions on S9.6 IFs in this case.

Thus, we have found no evidence for a Rad51-facilitated strand invasion from RNAs produced in trans. Further arguing against any major role of this recombinase in R loop metabolism or function, none of the so far reported DNA:RNA hybrid interactomes has identified RAD51 (Cristini et al., 2018; Nadel et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). The fact that, in vitro, RecA can catalyze an inverse DNA strand exchange reaction with DNA or RNA thus promoting the assimilation of a transcript into duplex DNA (Kasahara et al., 2000; Zaitsev and Kowalczykowski, 2000) does not argue that this is the case for unscheduled recombinogenic R loops in vivo. More likely, the biological significance of this process relies on its use for replication initiation of prokaryotic cells as originally proposed (Zaitsev and Kowalczykowski, 2000), for replication-dependent recombination to restart stalled forks (Pomerantz and O'Donnell, 2008) or even for transcription-induced origin-independent replication (Stuckey et al., 2015). Hence, DNA:RNA hybridization could occur in trans under regulated conditions but not spontaneously as unscheduled and harmful structures that would put genome integrity into risk. Thus, the assimilation of a transcript into a duplex DNA in trans would be tightly regulated and limited to specific reactions such as the case of telomerase or CRISPR and possibly other proteins yet to be discovered. For other cases, such as that of the GADP45 factor that binds to promoters harboring hybrids formed by lncRNAs (Arab et al., 2019), it is unclear whether such hybrids are formed in trans and in a GADP45-dependent manner.

Altogether, our results suggest that RNAs do not form hybrids in trans, so that the previously reported induction of Rad51-dependent ectopic genetic instability would be explained by R loop-mediated DNA breaks in cis.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference |

Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

W303 background strains with different gene deletions | various | (See Materials and methods section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Yeast expression plasmids and recombination systems | various | (See Materials and methods section) | |

| Sequence-based reagent | Primers for DRIP and RT-PCR | Condalab | (See Materials and methods section) | |

| Antibody | Cy3 conjugated anti-mouse (goat monoclonal) | Jackson laboratories | Cat# 115-165-003, RRID:AB_2338680 | IF (1:1000) |

| Antibody | S9.6 anti DNA:RNA hybrids (mouse monoclonal) | ATCC Hybridoma cell line | Cat# HB-8730, RRID:CVCL_G144 |

DRIP (1 mg/ml) and IF (1:1000) |

| Commercial assay, kit | Macherey-Nagel DNA purification | Macherey- Nagel | Cat# 740588.250 |

|

| Commercial assay, kit | Qiagen’s RNeasy | Quiagen | Cat# 75162 | |

| Commercial assay, kit | Reverse Transcription kit | Qiagen | Cat # 205311 | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Zymolyase 20T | US Biological | Z1001 | (50 mg/ml) |

| Chemical compound, drug | Doxycyclin hyclate | Sigma-Aldrich | D9891 | (5 mg/ml) |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Proteinase K (PCR grade) | Roche | Cat # 03508811103 | |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Rnase A | Roche | Cat # 10154105103 | |

| Software, algorithm | GraphPad Prism V8.4.2 | GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA |

RRID:SCR_002798 | |

| Other | iTaq Universal SYBR Green | Bio-RAD | Cat # 1725120 | |

| Other | DAPI stain | Invitrogen | D1306 | 1 µg/mL |

Yeast strains and Plasmids

Strains used were the wild-type W303-1A (MATa ade2-1 can1- 100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 rad5-G535R) and its isogenic hpr1∆::HIS3 mutant U678-1C (MATa) and U678-4C (MATα), mft1∆::KANMX mutant (WMK.1A) (Chávez and Aguilera, 1997), rnh1Δ::KANMX rnh201Δ::KANMX (RNH-R), rad51∆::KANMX (WSR51.4A) (González-Barrera et al., 2002), and hpr1∆::HIS3MX rad51∆::KANMX (HPR51.15A) from this study. rnh1Δ::KAN rnh201Δ::KAN (HRN2.8A) and the wild-type HRN2.8A were from Huertas and Aguilera, 2003. Wild-type (WGLZN) and hpr1∆HIS3 mutant were made in this study by insertion of the GL-LacZ::NATMX at the LEU2 locus in Chromosome III of a W303-1A strain corrected for RAD5 (Moriel-Carretero and Aguilera, 2010).

Yeast plasmids pCM179, pCM184, pCM189 and pCM190 were previously published (Garí et al., 1997). pRS314-GL-LacZ (Piruat and Aguilera, 1998) and pRS314-GL-LacZi plasmids with recombination systems were built as follows. The BamHI fragment containing the LacZ sequence from pPZ (Straka and Hörz, 1991), was inserted in both sense and antisense orientations with respect to the promoter, respectively, into the BglII site of pRS314GLB (Piruat and Aguilera, 1998). pCM184TL-lacZ (Santos-Pereira et al., 2013) pRS416 and pRS416-GALlacZ were described previously (Prado et al., 1997). pCM184:AID was built by inserting the AID ORF from pCM189:AID (Santos-Pereira et al., 2013) into the NotI site of pCM190. pCM190-tet::LacZ400 was built by cloning the KpnI-BamHI 400 bp fragment of the 3' from the LacZ gene into KpnI-BamHI digested pCM190. Plasmids pCM189:AID, pCM184:RNH1 (Santos-Pereira et al., 2013), and pWJ1344 (Lisby et al., 2001) were also previously published.

Yeast transformation

Yeast transformation was performed using the lithium acetate method as previously described (Gietz et al., 1995).

Recombination assays

Cells transformed were grown in selective media containing 2% glucose and 5 μg/mL of doxycycline (kept in the dark) to repress transcription from the GAL1 and tet promoter, respectively. Recombination frequencies were calculated as previously described as means of at least three median frequencies obtained each from six independent colonies isolated in the appropriate medium for the selection of the required plasmids (Gómez-González et al., 2011). Briefly, transformants were cultured for at 3–4 days (until acquiring similar colony size) in the appropriate selective media containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose and recombinants were obtained by plating appropriate dilutions in selective medium. To calculate total number of cells, plates with the same requirements as for the original transformation were used. All plates were grown for 3–4 days at 30°C. The average and SEM of at least three independent transformants was plotted for each figure but the numerical data can be seen in Figure 2—source data 1, Figure 4—source data 1, Figure 5—source data 1 and Figure 6—source data 1.

Transcription analysis

Mid-log cultures were grown with either glucose or galactose and with or without 5 μg/ml doxycycline (kept in the dark). Total RNA was obtained using Qiagen’s RNeasy kit and used for cDNA synthesis with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit with random primers (Qiagen) according to instruction. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using iTaq universal SYBR Green (Biorad) with a 7500 Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Primers sequences used for this analysis were LacZT1-Fw (GCGCCGTGGCCTGAT), LacZT1-Rv (GTGCAGCGCGATCGTAATC), Intergenic-Fw (TGTTCCTTTAAGAGGTGATGGTGAT) and Intergenic-Rv (GTGCGCAGTACTTGTGAAAACC). The exact values obtained are shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 1.

DRIP assays

DNA:RNA hybrids were measured in cultures with either glucose or galactose and either with or without 5 μg/ml doxycycline (kept in the dark). Cultures were collected, washed with chilled water, resuspended in 1.4 mL spheroplasting buffer (1 M sorbitol, 10 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mg/ml Zymoliase 20T) and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The spheroplasts were pelleted (5 min at 7000 rpm) rinsed with water and homogeneously resuspended in 1.65 mL of buffer G2 (800 mM Guanidine HCl, 30 mM Tris-Cl pH 8, 30 mM EDTA pH 8, 5% Tween-20, 0.5% Triton X-100). Samples were treated with 40 μl 10 mg/ml RNase A for 30 min at 37°C and 75 μl of 20 mg/ml proteinase K (Roche) for 1 hr at 50°C. DRIP was performed mainly as described (Ginno et al., 2012) with few differences. DNA was extracted gently with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 24:1. Precipitated DNA, washed twice with 70% EtOH, resuspended gently in TE and digested overnight with 50 U of HindIII, EcoRI, BsrGI, XbaI and SspI, 2 mM spermidine and 2.5 μl BSA 10 mg/ml. Half of the DNA was treated with 8 μL RNase H (New England BioLabs) overnight 37°C as RNase H control. RNA-DNA hybrids were immunoprecipitated using S9.6 monoclonal antibody (hybridoma cell line HB-8730) coupled to Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen) for 2 hr at 4°C and washed 3 times with 1x binding buffer. DNA was eluted in 100 μL elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) treated 45 min with 7 μL proteinase K 20 mg/ml at 55°C and purified with Macherey-Nagel DNA purification kit. Primers sequences used for this analysis were LacZT1-Fw (GCGCCGTGGCCTGAT) and LacZT1-Rv (GTGCAGCGCGATCGTAATC). The average and SEM of at least three independent transformants was plotted but the numerical data can be seen in Figure 3—source data 1.

Detection of Rad52-YFP foci

Spontaneous Rad52-YFP foci from mid-log growing cells carrying plasmid pWJ1344 were visualized and counted by fluorescence microscopy in a Leica DC 350F microscope, as previously described (Lisby et al., 2001). More than 200 S/G2 cells where inspected for each experimental replica. The average and SEM of at least three independent transformants was plotted but the numerical data can be seen in Figure 7—source data 1.

S9.6 immunofluorescence of yeast chromosome spreads

The procedure performed is similar to Chan et al., 2014 with some modifications. Briefly, mid-log cultures (OD600 = 0.5–0.8) were grown at 30°C; 10 ml of them were collected, washed in cold spheroplasting buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 0.1 M potassium phosphate and 0.5 MgCl2 at pH 7) and then digested by adding 10 mM DTT and 150 mg/ml of Zymolyase 20T to the same buffer. The digestion was performed for 10 min (37°C) and stopped by mixing the samples with the solution 2 (0.1 M MES, 1M sorbitol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM MgCl2, pH 6.4). Later, spheroplasts were centrifuged carefully 8 min at 800 rpm, lysed with 1% vol/vol Lipsol and fixed on slides using Fixative solution (4% paraformaldehyde/3.4% sucrose). The spreading was carried out using a glass rod and the slides were dried from 2 hr to overnight in the extraction hood.

For the immuno-staining, the slides were first washed in PBS 1X in coplin jars and then blocked in blocking buffer (5% BSA, 0.2% milk in PBS 1X) over 10 min in humid chambers. Afterwards, slides were incubated with the primary monoclonal antibody S9.6 (1 mg/ml) in a humid chamber 1 hr at 23°C. After washing the slides with PBS 1X for 10 min, the slides were incubated 1 hr at 23°C in the dark with the secondary antibody Cy3 conjugated goat anti-mouse (Jackson laboratories, #115-165-003) diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer. Finally, the slides were mounted with 50 μl of Vectashield (Vector laboratories, CA) with 1X DAPI and sealed with nail polish. For each experiment, more than 100 nuclei were visualized and counted to obtain the fraction of nuclei with DNA:RNA hybrids. The average and SEM of at least three independent transformants was plotted but the numerical data can be seen in Figure 7—source data 1.

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BFU2016-75058-P) and the European Union (FEDER). BG-G was funded by a grant from the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Belén Gómez-González, Email: gomezb@us.es.

Andrés Aguilera, Email: andres.aguilera@cabimer.es.

Wolf-Dietrich Heyer, University of California, Davis, United States.

Jessica K Tyler, Weill Cornell Medicine, United States.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad BFU2016-75058-P to Andrés Aguilera.

European Regional Development Fund to Andrés Aguilera.

Spanish Association Against Cancer to Belén Gómez-González.

Additional information

Competing interests

Reviewing editor, eLife.

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - review and editing.

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Formal analysis.

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing.

Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing.

Additional files

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files. Source data files have been provided for all graphs.

References

- Aguilera A, Gómez-González B. DNA-RNA hybrids: the risks of DNA breakage during transcription. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2017;24:439–443. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro D, Lisby M, Rothstein R. Genome-wide analysis of Rad52 foci reveals diverse mechanisms impacting recombination. PLOS Genetics. 2007;3:e228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab K, Karaulanov E, Musheev M, Trnka P, Schäfer A, Grummt I, Niehrs C. GADD45A binds R-loops and recruits TET1 to CpG island promoters. Nature Genetics. 2019;51:217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel F, Lucero L, Christ A, Mammarella MF, Jegu T, Veluchamy A, Mariappan K, Latrasse D, Blein T, Liu C, Benhamed M, Crespi M. R-Loop mediated trans action of the APOLO long noncoding RNA. Molecular Cell. 2020;77:1055–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V, Barroso SI, García-Rubio ML, Tumini E, Herrera-Moyano E, Aguilera A. BRCA2 prevents R-loop accumulation and associates with TREX-2 mRNA export factor PCID2. Nature. 2014;511:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature13374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ. Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS Journal. 2009;276:1494–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YA, Aristizabal MJ, Lu PY, Luo Z, Hamza A, Kobor MS, Stirling PC, Hieter P. Genome-wide profiling of yeast DNA:rna hybrid prone sites with DRIP-chip. PLOS Genetics. 2014;10:e1004288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DD, Hauswirth WW, Clayton DA. Replication priming and transcription initiate from precisely the same site in mouse mitochondrial DNA. The EMBO Journal. 1985;4:1559–1567. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez S, Beilharz T, Rondón AG, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Svejstrup JQ, Lithgow T, Aguilera A. A protein complex containing Tho2, Hpr1, Mft1 and a novel protein, Thp2, connects transcription elongation with mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The EMBO Journal. 2000;19:5824–5834. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez S, García-Rubio M, Prado F, Aguilera A. Hpr1 is preferentially required for transcription of either long or G+C-Rich DNA sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21:7054–7064. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7054-7064.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez S, Aguilera A. The yeast HPR1 gene has a functional role in transcriptional elongation that uncovers a novel source of genome instability. Genes & Development. 1997;11:3459–3470. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier SC, Wang S, Ma WK, Al Husini N, Dhoondia Z, Ansari A, Pascuzzi PE, Tran EJ. Regulated formation of lncRNA-DNA hybrids enables faster transcriptional induction and environmental adaptation. Molecular Cell. 2016;61:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Puget N, Lin YL, Clouaire T, Aguirrebengoa M, Rocher V, Pasero P, Canitrot Y, Legube G. Senataxin resolves RNA:dna hybrids forming at DNA double-strand breaks to prevent translocations. Nature Communications. 2018;9:533. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02894-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K. Mammalian telomeres and telomerase. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2000;12:378–383. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristini A, Groh M, Kristiansen MS, Gromak N. RNA/DNA hybrid interactome identifies DXH9 as a molecular player in transcriptional termination and R-Loop-Associated DNA damage. Cell Reports. 2018;23:1891–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro G, Whelan DR, Howard SM, Vitelli V, Renaudin X, Adamowicz M, Iannelli F, Jones-Weinert CW, Lee M, Matti V, Lee WTC, Morten MJ, Venkitaraman AR, Cejka P, Rothenberg E, d'Adda di Fagagna F. BRCA2 controls DNA:rna hybrid level at DSBs by mediating RNase H2 recruitment. Nature Communications. 2018;9:5376. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M, Phoenix P, Menzel R, Massé E, Liu LF, Crouch RJ. Overexpression of RNase H partially complements the growth defect of an Escherichia coli Delta topA mutant: r-loop formation is a major problem in the absence of DNA topoisomerase I. PNAS. 1995;92:3526–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan HY, Cheng KK, Klein HL. Mutations in the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery suppress the hyperrecombination mutant hpr1 Delta of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;142:749–759. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Muse T, Aguilera A. R loops: from physiological to pathological roles. Cell. 2019;179:604–618. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pichardo D, Cañas JC, García-Rubio ML, Gómez-González B, Rondón AG, Aguilera A. Histone mutants separate R loop formation from genome instability induction. Molecular Cell. 2017;66:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Rubio ML, Pérez-Calero C, Barroso SI, Tumini E, Herrera-Moyano E, Rosado IV, Aguilera A. The fanconi Anemia pathway protects genome integrity from R-loops. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11:e1005674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garí E, Piedrafita L, Aldea M, Herrero E. A set of vectors with a tetracycline-regulatable promoter system for modulated gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:837–848. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199707)13:9<837::AID-YEA145>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Willems AR, Woods RA. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginno PA, Lott PL, Christensen HC, Korf I, Chédin F. R-loop formation is a distinctive characteristic of unmethylated human CpG island promoters. Molecular Cell. 2012;45:814–825. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González B, Felipe-Abrio I, Aguilera A. The S-Phase checkpoint is required to respond to R-Loops accumulated in THO mutants. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29:5203–5213. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00402-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González B, Ruiz JF, Aguilera A. Genetic and molecular analysis of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2011;745:151–172. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-129-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González B, Aguilera A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase action is strongly stimulated by mutations of the THO complex. PNAS. 2007;104:8409–8414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Barrera S, García-Rubio M, Aguilera A. Transcription and double-strand breaks induce similar mitotic recombination events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;162:603–614. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartono SR, Malapert A, Legros P, Bernard P, Chédin F, Vanoosthuyse V. The affinity of the S9.6 Antibody for Double-Stranded RNAs Impacts the Accurate Mapping of R-Loops in Fission Yeast. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2018;430:272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Moyano E, Mergui X, García-Rubio ML, Barroso S, Aguilera A. The yeast and human FACT chromatin-reorganizing complexes solve R-loop-mediated transcription-replication conflicts. Genes & Development. 2014;28:735–748. doi: 10.1101/gad.234070.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, Aguilera A. Cotranscriptionally formed DNA:rna hybrids mediate transcription elongation impairment and transcription-associated recombination. Molecular Cell. 2003;12:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, Clikeman JA, Bates DB, Kogoma T. RecA protein-dependent R-loop formation in vitro. Genes & Development. 2000;14:360–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskin H, Shen Y, Huang F, Patel M, Yang T, Ashley K, Mazin AV, Storici F. Transcript-RNA-templated DNA recombination and repair. Nature. 2014;515:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature13682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König F, Schubert T, Längst G. The monoclonal S9.6 antibody exhibits highly variable binding affinities towards different R-loop sequences. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0178875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Germain DR, Poon HY, Hildebrandt MR, Monckton EA, McDonald D, Hendzel MJ, Godbout R. DEAD box 1 facilitates removal of RNA and homologous recombination at DNA Double-Strand breaks. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2016;36:2794–2810. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00415-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Manley JL. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell. 2005;122:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby M, Rothstein R, Mortensen UH. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination centers during S phase. PNAS. 2001;98:8276–8282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121006298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna R, Rondón AG, Pérez-Calero C, Salas-Armenteros I, Aguilera A. The THO complex as a paradigm for the prevention of cotranscriptional R-Loops. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 2019;84:105–114. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2019.84.039594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischo HE, Gómez-González B, Grzechnik P, Rondón AG, Wei W, Steinmetz L, Aguilera A, Proudfoot NJ. Yeast Sen1 helicase protects the genome from transcription-associated instability. Molecular Cell. 2011;41:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriel-Carretero M, Aguilera A. A postincision-deficient TFIIH causes replication fork breakage and uncovers alternative Rad51- or Pol32-mediated restart mechanisms. Molecular Cell. 2010;37:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J, Athanasiadou R, Lemetre C, Wijetunga NA, Ó Broin P, Sato H, Zhang Z, Jeddeloh J, Montagna C, Golden A, Seoighe C, Greally JM. RNA:dna hybrids in the human genome have distinctive nucleotide characteristics, chromatin composition, and transcriptional relationships. Epigenetics & Chromatin. 2015;8:46. doi: 10.1186/s13072-015-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohle C, Tesorero R, Schermann G, Dobrev N, Sinning I, Fischer T. Transient RNA-DNA hybrids are required for efficient Double-Strand break repair. Cell. 2016;167:1001–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Gómez-González B, Aguilera A. DNA repair in mammalian cells: dna double-strand break repair: how to fix a broken relationship. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences : CMLS. 2009;66:1039–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8740-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Aguilera A. Complex chromosomal rearrangements mediated by break-induced replication involve structure-selective endonucleases. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8:e1002979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen RD, Soni DV, Wollman R, Hahn AT, Yee MC, Guan A, Hesley JA, Miller SC, Cromwell EF, Solow-Cordero DE, Meyer T, Cimprich KA. A genome-wide siRNA screen reveals diverse cellular processes and pathways that mediate genome stability. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza A, Wright WD, Heyer WD. Multi-invasions are recombination byproducts that induce chromosomal rearrangements. Cell. 2017;170:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piruat JI, Aguilera A. A novel yeast gene, THO2, is involved in RNA pol II transcription and provides new evidence for transcriptional elongation-associated recombination. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17:4859–4872. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz RT, O'Donnell M. The replisome uses mRNA as a primer after colliding with RNA polymerase. Nature. 2008;456:762–766. doi: 10.1038/nature07527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado F, Piruat JI, Aguilera A. Recombination between DNA repeats in yeast hpr1delta cells is linked to transcription elongation. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16:2826–2835. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puget N, Miller KM, Legube G. Non-canonical DNA/RNA structures during Transcription-Coupled Double-Strand break repair: roadblocks or bona fide repair intermediates? DNA Repair. 2019;81:102661. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A, Machin N, Stahl FW. A DNA double chain break stimulates triparental recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PNAS. 1989;86:6225–6229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D, Zhang Z, Lu Z, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Competition between the RNA transcript and the nontemplate DNA strand during R-loop formation in vitro: a nick can serve as a strong R-loop initiation site. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2010;30:146–159. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00897-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JF, Gómez-González B, Aguilera A. Chromosomal translocations caused by either pol32-dependent or pol32-independent triparental break-induced replication. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29:5441–5454. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Pereira JM, Herrero AB, García-Rubio ML, Marín A, Moreno S, Aguilera A. The Npl3 hnRNP prevents R-loop-mediated transcription-replication conflicts and genome instability. Genes & Development. 2013;27:2445–2458. doi: 10.1101/gad.229880.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab RA, Nieminuszczy J, Shah F, Langton J, Lopez Martinez D, Liang CC, Cohn MA, Gibbons RJ, Deans AJ, Niedzwiedz W. The fanconi Anemia pathway maintains genome stability by coordinating replication and transcription. Molecular Cell. 2015;60:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S, Camino LP, Aguilera A. Human mitochondrial degradosome prevents harmful mitochondrial R loops and mitochondrial genome instability. PNAS. 2018;115:11024–11029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807258115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz R, Sulthana S, Hartono SR, Malig M, Benham CJ, Chedin F. Interplay between DNA sequence and negative superhelicity drives R-loop structures. PNAS. 2019;116:6260–6269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819476116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straka C, Hörz W. A functional role for nucleosomes in the repression of a yeast promoter. The EMBO Journal. 1991;10:361–368. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey R, García-Rodríguez N, Aguilera A, Wellinger RE. Role for RNA:dna hybrids in origin-independent replication priming in a eukaryotic system. PNAS. 2015;112:5779–5784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501769112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y, Yadav T, Duan M, Tan J, Xiang Y, Gao B, Xu J, Liang Z, Liu Y, Nakajima S, Shi Y, Levine AS, Zou L, Lan L. ROS-induced R loops trigger a transcription-coupled but BRCA1/2-independent homologous recombination pathway through CSB. Nature Communications. 2018;9:4115. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tous C, Aguilera A. Impairment of transcription elongation by R-loops in vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;360:428–432. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahba L, Gore SK, Koshland D. The homologous recombination machinery modulates the formation of RNA–DNA hybrids and associated chromosome instability. eLife. 2013;2:e00505. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IX, Grunseich C, Fox J, Burdick J, Zhu Z, Ravazian N, Hafner M, Cheung VG. Human proteins that interact with RNA/DNA hybrids. Genome Research. 2018;28:1405–1414. doi: 10.1101/gr.237362.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellinger RE, Prado F, Aguilera A. Replication fork progression is impaired by transcription in hyperrecombinant yeast cells lacking a functional THO complex. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26:3327–3334. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3327-3334.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Kato R, Hagiwara Y, Shiotani B, Yamauchi M, Nakada S, Shibata A, Miyagawa K. Human Rad52 promotes XPG-Mediated R-loop processing to initiate Transcription-Associated homologous recombination repair. Cell. 2018;175:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Chedin F, Hsieh CL, Wilson TE, Lieber MR. R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nature Immunology. 2003;4:442–451. doi: 10.1038/ni919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev EN, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel pairing process promoted by Escherichia coli RecA protein: inverse DNA and RNA strand exchange. Genes & Development. 2000;14:740–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]