Abstract

Young adults consume most of their alcohol by binge drinking, and more than one third report binge drinking in the past month. Some will transition out of excessive drinking, while others will maintain or increase alcohol use into adulthood. Public health campaigns depicting negative consequences of drinking have shown some efficacy at reducing this behavior. However, substance use in dependent individuals is governed in part by automatic or habitual responses to drug cues rather than the consequences. This study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure neural responses to drinking cues and drinking cues paired with antidrinking messages among young adults who binge drink (N=30). This study also explored responses to smoking cues and antismoking messages. Neural responses were also compared between drinking/smoking and neutral cues. Self-reported drinking and smoking was collected at baseline, post-scan and one-month. Results indicate that activity in the ventral striatum –implicated in reward processing –was lower for drinking cues paired with antidrinking messages than drinking cues. This difference was less pronounced in young adults who reported greater baseline past month drinking quantity. Past month drinking quantity decreased from baseline to one month. Further, young adults who showed higher activity in the medial prefrontal cortex –implicated in processing message self-relevance –during antidrinking messages reported a greater decrease in past month drinking frequency from baseline to one month. Findings may help to identify young adults who are at risk for continued heavy drinking in adulthood and inform interventions aimed to reduce drinking and reward in young adults.

Keywords: Alcohol use, antidrinking messages, devaluation, health messaging, young adult

INTRODUCTION

Young adulthood (ages 18–25)1 is a critical developmental period typically associated with increased health-risk behaviors including alcohol use2. Alcohol use typically begins in late adolescence (ages 16–20) when youth are experiencing dramatic neural, physical, emotional and social changes3. Alcohol use then escalates during the transition to young adulthood, with increased independence and opportunity and decreased parental guidance and monitoring2. Nearly 60% of young adults reported alcohol use in the past month4.

Alcohol use in young adulthood is often excessive4–6, including meeting criteria for binge drinking –consuming more than five drinks on one occasion for males or more than four drinks on one occasion for females4, 7. Young adults consume more than 90% of their alcohol by binge drinking8, with more than one third reporting binge drinking in the past month4. Nearly ten percent of young adults report heavy drinking –binge drinking on five or more days in the past month4. Excessive drinking among young adults is associated with negative consequences6, 9, including those causally related to drinking, such as blackouts, hangover, nausea and vomiting, and others for which the role of alcohol is more difficult to establish, such as risky sexual behavior, fighting and academic failure6, 9, 10. The highest rates of past year AUD occur in this age group 4–6, with 29% of emerging adults meeting DSM 5 criteria for AUD in the past year11. Furthermore, heavy drinking during young adulthood is strongly predictive of AUD and alcohol-related problems during adulthood12.

There is a decline in drinking and drinking-related problems across the mid-to-late twenties13, with most young adults transitioning out of problematic drinking14, 15. “Maturing out”16 appears to take place as young adults assume the roles and responsibilities of adulthood, but there are also relevant changes in personality17, as well as developmental changes in risk-taking behaviors15. At the same time, there are neurodevelopmental changes such as ongoing cortical myelination of association cortex projections and the emergence of adult patterns of structural and functional neural connectivity18. However, information is limited about how to differentiate young adults who will mature out of problematic drinking from those who will not. This information may be critical to inform targeted interventions and reduce the overall public health impact of alcohol use among young adults.

Public health campaigns depicting the negative consequences of alcohol use have had some success in impacting drinking decisions among young adults. There is strong evidence that such campaigns are effective in changing knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about drinking19, and initial evidence to support direct changes in alcohol consumption20. Youth who disapprove of heavy drinking and who consider drinking harmful are less likely to drink20. However, one prominent theory of addiction posits that substance use in dependent individuals is governed by habitual responding to drug cues rather than by the consequences (perceived or experienced) of these behaviors21. Evidence from animal models indicates that prolonged substance use is associated with greater resistance to the devaluation of drug reward22. For example, rats with a longer history of ethanol self-administration show greater resistance to ethanol devaluation when the intoxicating effects are paired with aversive effects of lithium chloride23. Continued responding, or reduced sensitivity to devaluation, is associated with habitual alcohol use24. The current study was designed to test how alcohol use among young adults related to their responsiveness to “devaluation” of drinking by exposure to messages about the negative consequences of drinking. This study was also designed to test whether recruitment of executive control strategies in response to antidrinking messages was related to future drinking behavior. A better understanding of these relationships could help identify those young adults at greatest risk of continued heavy drinking into adulthood –for example, those who are more resistant to devaluation or less responsive to antidrinking messages.

The current study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to test how young adults who reported past month binge drinking responded to antidrinking messages about the negative consequences of drinking. First, we tested the hypothesis that greater drinking levels, measured as past month drinking quantity and frequency, would be related to greater resistance to the “devaluation” of drinking behavior, measured as the difference in neural cue reactivity between drinking cues and drinking cues paired with antidrinking messages. To test this, cue-reactivity was measured in the ventral striatum (VS), a brain region implicated in reward-related cue-reactivity by meta-analyses of fMRI studies of drug-related cues25 and alcohol cues26. We tested the additional hypothesis that neural activation during exposure to antidrinking messages would be related to change in drinking levels at one month follow-up, based on a body of literature indicating that neural response to health messaging predicts change in future health behavior beyond self-report27. To test this, responses to antidrinking messages were measured in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), a brain region implicated in processing health messages28 and consistently reported in fMRI studies predicting future health behavior change from neural responses to health messages29. We additionally explored responses to smoking cues and antismoking messages. Such information could inform interventions aimed to reduce alcohol use and reward among young adults and help to differentiate those who will mature out of problematic drinking from those who will not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

Eligible participants took part in an fMRI study and completed pre- and post-scan surveys including a post-scan memory task. A follow-up survey was emailed to participants one month after their fMRI scan. All surveys were completed online using Yale Qualtrics Survey Tool (https://yalesurvey.qualtrics.com/).

Participants

Participants were eligible if they were between 18–25 years old and met criteria for binge drinking30 on at least one day in the past month. Participants were recruited regardless of smoking status. Participants were required to be English speaking because fMRI stimuli were presented in English; right-handed because fMRI stimuli were language-related31, 32; have no contraindication to MRI; no history of brain trauma or psychiatric disorders; and no daily substance use (except nicotine or alcohol). This study was conducted in in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and as approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee. All participants provided signed informed consent. Participant demographics and baseline tobacco and alcohol use characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant baseline demographics, tobacco and alcohol use

| Total N=30 | M n=13 | F n=17 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 20.9 (1.6) | 21.0 (1.2) | 20.8 (1.9) |

| Minority race/ethnicitya (n) | 12 | 3 | 9 |

| Education greater than high schoolb (n) | 25 | 11 | 14 |

| Binge days past month, mean (SD), days | 4.8 (2.8) | 6.4 (3.0) | 3.5 (1.8)** |

| Drinking frequency past month, mean (SD), days | 7.6 (4.7) | 9.8 (6.0) | 6.0 (2.5)* |

| Drinks per drinking day past month, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.3) |

| Maximum # drinks in 24 hours, mean (SD) | 11.5 (5.5) | 15.1 (6.4) | 8.8 (2.5)*** |

| Ever tried to cut down or quit (n) | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| BYAACQ (possible range 0–24) | 6.2 (4.0) | 7.9 (4.1) | 4.9 (3.5)* |

| Ever cigarette smoker (n) | 18 | 9 | 9 |

| Past month cigarette smoker (n) | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Past month cigarette quantity per day, mean (SD) | 1.4 (.54) | 1.3 (.50) | 1.7 (.58) |

| Past month cigarette frequency, mean (SD), days | 2.4 (1) | 2.0 (.87) | 3.0 (1.0) |

| Ever e-cigarette user (n) | 16c | 10 | 6* |

| Past month e-cigarette user (n) | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Past month e-cigarette frequency, mean (SD), days | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.5 (.71) | 1.7 (.58) |

| Non-completers (n) | 3 |

BYAACQ–Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire; M–males; F–females

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Race/ethnicity was: White Non-Hispanic (n=18); White Hispanic (n=2; Puerto Rican; Mexican American); Non-White Hispanic (n=1, Mexican/Mexicano); Black/African American (n=3); Indian (American) (n=2); Other Asian (n=1); Some other race Hispanic (n=2; Central or South American; Mexican American); and Some other race Non-Hispanic (n=1)

Education completed was high school (n=5), some college (n=14), Bachelor’s degree (n=11).

n=2 never cigarette smokers

Measures

PhenX Toolkit (https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/) protocols were used for sex, race, ethnicity and current educational attainment. Alcohol use behavior was measured using the PhenX protocols for past month drinking quantity (“Think specifically about the past 30 days, up to and including today. During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?”); frequency (“On the days that you drank during the past 30 days, how many drinks did you usually have each day? Count as a drink a can or bottle of beer; a wine cooler or a glass of wine, champagne, or sherry; a shot of liquor or a mixed drink or cocktail”); maximum drinks in 24 hours (“In your lifetime, what is the largest number of drinks you have ever had in a 24-hour period (including all types of alcohol)?”); by asking, “Have you ever tried to stop or cut down on drinking?” (yes/no); and for binge drinking (“During the last 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 (4 for females) or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol in a day? That would be the equivalent of at least 5 12-oz. cans or bottles of beer, 5 five-oz. glasses of wine, 5 drinks each containing one shot of liquor or spirits,” 0–30 days). The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ) was used to evaluate past month negative drinking consequences33. Smoking behavior was measured using the PhenX protocol for smoking status, with ever smokers completing additional protocols for past month smoking quantity and frequency. E-cigarette use was measured by asking about ever e-cigarette use and past month e-cigarette use frequency. Based on theory of planned behavior34, participants were asked, “Do you intend to engage in a binge drinking session over the next month?” (1=Definitely not, 7=Definitely will); ever cigarette smokers were asked, “Do you intend to smoke over the next month?” (1=Definitely not, 7=Definitely will); and ever e-cigarette users were asked, “Do you intend to use an e-cigarette over the next month?” (1=Definitely not, 7=Definitely will). Additionally, all participants were asked, “How strong is your urge to drink/smoke/use an electronic cigarette?” (1=Not at all, 7=The most I’ve ever felt).

fMRI acquisition

fMRI scanning took place at the Yale Magnetic Resonance Research Center using a 3T Siemens Magnetom Trio Tim scanner and 64 channel headcoil. A high-resolution 3D Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Gradient-Echo sequence was acquired in the sagittal plane (TR=2400 ms; TE=1.18 ms; bandwidth=610 Hz/Px; flip angle=8°; slice thickness=1 mm; field-of-view=256×256 mm; matrix=256×256). A T2*-weighted multiband echo planar imaging sequence was acquired with 75 slices and 2 mm isotropic voxels (TR=1 s, TE=30 ms, bandwidth=1894 Hz/Px, flip angle=55°, field-of-view=220×220 mm, matrix=110×110 mm, slice thickness=2 mm, no gap, multi-band factor=5).

fMRI task

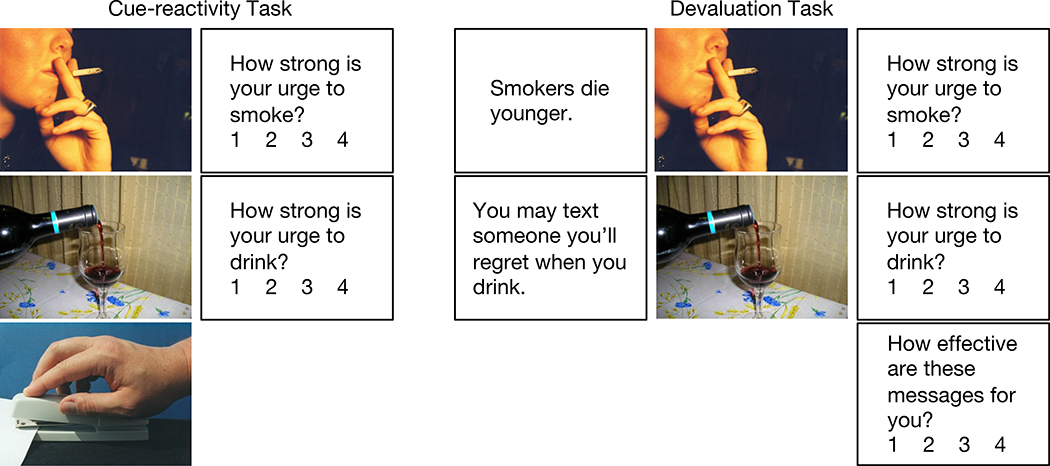

The fMRI session included a cue-reactivity task and a cue-devaluation task (Figure 1). For the cue-reactivity task, drinking, smoking and neutral cues were presented in a blocked design with five cues per block (15 s) followed by ratings and rest (15 s). Participants were asked to rate “How strong is your urge to drink” after drinking cues and “How strong is your urge to smoke” after smoking cues, from 1=No urge, 4=High urge, using a button box. Upon responding, a fixation cross appeared to indicate that they should rest. No rating was asked for neutral cues. Forty cues per condition were randomized in drinking, smoking or neutral blocks that were randomized across two six-minute runs (8 blocks per condition).

Figure 1. fMRI design.

A cue-reactivity task included blocks of five smoking, drinking or neutral cues, followed by ratings (specific to cue type) and rest, for eight blocks per run across two runs. Next, a “devaluation” task included blocks of five antidrinking or antismoking messages (presented as audio and text), followed by five drinking or smoking cues, followed by ratings and rest, for eight blocks per run across four runs.

For the cue-devaluation task, antidrinking or antismoking messages were first presented as simultaneous audio and text with five messages per block (25 s), followed by five drinking or smoking cues per block (15 s), followed by ratings and rest (15 s). Participants were asked again to rate their urge to drink or smoke and also to rate the effectiveness of the antidrinking or antismoking messages: “How effective are these messages for you?” from 1=Not at all, 4=Extremely. Upon responding, a fixation cross appeared to indicate that they should rest. Eighty antidrinking and eighty antismoking messages and the same 40 drinking and smoking cues were randomized in drinking or smoking blocks that were randomized across four seven-minute runs (16 blocks per condition).

Drinking, smoking and neutral cues were derived from available cue banks 35–38. Antidrinking and antismoking messages describing the social and health consequences of drinking and smoking were derived from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism39, American Heart Association40, Truth campaign41 and similar sources. Messages were at the 6th grade reading level and controlled for the number of words, syllables, and characters across message types. Messages were audio-recorded by a professional age-matched male or female actor (randomly assigned).

Post-scan survey

A post-scan survey was administered immediately following fMRI. First, a recognition memory task presented 10 previously shown and 10 new antidrinking or antismoking messages (each), and participants were asked “Have you encountered this message before” (yes/no). The order of the messages was randomized for each participant. Additionally, the same baseline questions were asked evaluating binge drinking attitudes and behaviors, intent to smoke, intent to quit smoking, and urge to drink/smoke/use an e-cigarette.

One month follow-up survey

A follow-up survey was administered approximately one month following fMRI (mean 32 days, range 30–36 days) and included the following items from the previous surveys: alcohol 30-day quantity and frequency, smoking and e-cigarette use (ever use, past 30-day use), binge drinking attitudes and behaviors, intent to smoke, intent to quit smoking, and urge to drink/smoke/use an e-cigarette.

fMRI preprocessing and analysis

Imaging data were analyzed in SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/). Functional images were realigned for motion correction, and the structural image was co-registered to the mean functional image and segmented. All images were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute template, resliced into 2 mm3 voxels, and smoothed using a 4 mm Gaussian kernel. Artifact Detection Tools (ART; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/artifact_detect) was used to identify outliers in mean global intensity (>3 SD from the mean) and motion (>1 mm). The cue-reactivity task was modeled using regressors for: drinking cues, smoking cues, neutral cues, ratings, and fixation. The cue-devaluation task was modeled separately using regressors for: antidrinking messages, drinking cues, antismoking messages, smoking cues, ratings, and fixation. Regressors of no interest were included for motion parameters and outliers identified by ART. Conditions were modeled using a boxcar function convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function, and regressors were fit the general linear model in SPM12. Region of interest (ROI) analysis was performed using 10 mm spheres centered on independently-sourced, functionally-defined peaks for the VS and MPFC. The VS ROI was defined based on an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of fMRI studies of drug cue-reactivity25 (drug versus control cues; [9, 10, –5]; Figure 2A). The MPFC ROI was defined based on a prior study predicting behavior change in response to health messaging28 (correlation between whole brain activity during presentation of persuasive messages and health behavior change, controlling for intention and attitude change; t=3.27; [–8, 52, –10]; Figure 3A). MarsBaR (http://marsbar.sourceforge.net/) was used to extract data from each functional image to a time course for each voxel in each ROI, calculate a summary time course as the mean voxel value in each ROI, estimate the model with the ROI data and apply a contrast to derive effect sizes for each ROI. Statistical analyses were then performed on extracted ROI activity.

Figure 2. Responses to drinking cues.

A) Ventral striatum (VS) region of interest; B) VS activity for drinking cues and devalued drinking cues versus neutral cues; C) correlation between baseline past month drinking quantity and the difference in VS activity for devalued drinking cues versus drinking cues; D) correlation between initial VS activity for drinking cues and post-scan memory for antidrinking messages.

Figure 3. Responses to antidrinking messages.

A) Medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) region of interest; B) past month drinking quantity at baseline and one month follow-up; C) past month drinking frequency at baseline and one month follow-up; D) correlation between MPFC activity during exposure to antidrinking messages and follow-up minus baseline change in past month drinking frequency.

Statistical analysis

Independent samples t-tests were used to compare baseline past month alcohol use by self-reported sex/gender. Paired samples t-tests were used to compare VS activity between drinking/smoking cues and neutral cues, and to compare VS activity between drinking/smoking cues and devalued drinking/smoking cues. The difference in VS activity was calculated between drinking/smoking cues and devalued drinking/smoking cues, both compared with neutral cues, and Pearson’s correlations were used to test for a relationship between difference in VS activity and past month drinking/smoking frequency and quantity. Linear regression was used to test for an effect of sex/gender on the identified relationship between difference in VS activity and past month drinking quantity. Pearson’s correlations were used to test for a relationship between VS activity in response to drinking/smoking cues and post-scan recognition memory for antidrinking/antismoking messages. Repeated measures analyses of variance were used to test for changes in urge and intent to binge drink/drink/smoke/use an e-cigarette across time points (pre/post/follow-up). Paired samples t-tests were used to compare past month drinking frequency and quantity between baseline (pre-scan) and one month follow-up, Bonferroni corrected for two t-tests. Changes in past month drinking/smoking frequency and quantity were calculated as follow-up minus baseline, and Pearson’s correlations were used to test for a relationship between MPFC response to antidrinking/antismoking messages and follow-up minus baseline changes in past month drinking/smoking. Linear regressions were used to test for effects of sex/gender, post- minus pre-scan intent to binge drink, ratings of effectiveness of antidrinking messages, and post-scan memory for antidrinking messages, on the identified relationship between MPFC response and follow-up minus baseline change in past month drinking frequency. All statistical analyses used 0.05 as the cutoff for significance.

RESULTS

Responses to drinking cues

VS activity was higher for drinking cues versus neutral cues (t(29)=4.2, p<.001). VS activity was lower for devalued drinking cues than drinking cues (t(29)=4.02, p<.001, d’=.73; Figure 2B). The difference in VS activity between devalued drinking cues and drinking cues was correlated with baseline past-month drinking quantity (r=–.44, p=.015; Figure 2C), such that greater baseline past month drinking quantity was related to less of a decrease in VS activity for devalued drinking cues compared to drinking cues. This finding held when controlling for sex/gender (β=.47, p=.01). No relationship was found between the difference in VS activity between devalued drinking cues and drinking cues and baseline past month drinking frequency (p=.47). Participants scored on average 7.0 ± 2.1 (out of 12) on the post-scan memory test for antidrinking messages. Higher VS activity in response to drinking cues versus neutral cues was correlated with poorer post-scan memory for antidrinking messages (r=–.47, p=.009; Figure 2D).

Responses to antidrinking messages

Antidrinking messages were rated as effective (significantly different from 1=Not at all effective; t(29)=11.44, p<.001; mean rating 2.4 ± .67 out of 4=Extremely effective). Intent to binge drink decreased across time points (F(27)=11.23, p<.001), with a decrease from pre- to post-scan (p<.001) and no change from post-scan to follow-up (p=.45). Urge to drink decreased across time points (F(27)=8.13, p=.002), with a decrease from pre- to post-scan (p<.001) and no change from post-scan to follow-up (p=.13). Past month drinking quantity decreased from baseline to follow-up (t(28)=2.91, corrected p=.014; Figure 3B). Past month drinking frequency did not change from baseline to follow-up (p=.32; Figure 3C).

MPFC activity during exposure to antidrinking messages was correlated with change in past month drinking frequency from baseline to follow-up (r=–.39, p=.038; Figure 3D), such that higher MPFC activity during antidrinking messages was related to a greater reduction in past month drinking frequency at follow-up. This finding held when controlling for sex/gender (β= –.41, p=.023); post- minus pre-scan change in intent to binge drink (β= –.39, p=.042); ratings of effectiveness of antidrinking messages (β= –.38, p=.044); and post-scan memory for antidrinking messages (β= –.38, p=.047). No relationship was found between MPFC activity during exposure to antidrinking messages and change in past month drinking quantity from baseline to follow-up (p=.80).

Responses to smoking cues

VS activity did not differ between smoking cues and neutral cues overall (t(29)=.88, p=.39) or for ever-smokers (t(17)=.03, p=.98). VS activity was lower for devalued smoking cues than smoking cues (t(29)=3.35, p=.002, d’=.61). This effect was driven by a decrease in VS activity for devalued smoking cues compared to smoking cues for ever-smokers (t(17)=3.2, p=.006, d’=.74) but not for never-smokers (t(11)=1.4, p=.20, d’=.40; Figure 4). No relationship was found between the difference in VS activity between devalued smoking cues and smoking cues and baseline past month smoking frequency (p=.51) or quantity (p=.44; n=7). Participants scored on average 8.6 ± 1.4 (out of 12) on the post-scan memory test for antismoking messages. No relationship was found between VS activity in response to smoking cues and post-scan memory for antismoking messages overall (p=.96) or for ever-smokers (p=.46, n=18).

Figure 4. Responses to smoking cues.

VS activity for smoking cues and devalued smoking cues versus neutral cues for A) ever-smokers and B) never smokers.

Responses to antismoking messages

Antismoking messages were rated as effective (t(29)=13.58, p<.001; mean rating 2.8 ± .72). Intent to smoke was low (baseline intent 2.3 ± 1.3 out of 7) and did not change across time points (F(14)=2.4, p=.12; only measured for ever-smokers). Urge to smoke was low (baseline urge 1.2 ± .5) and did not change across time points overall (F(27)=.63, p=.54) or for ever-smokers (F(15)=1.04, p=.38). For participants who reported baseline past month smoking (n=5), there was no change from baseline to follow-up in past month smoking frequency (baseline, 2.8 ± .8 days; follow-up, 3.4 ± 1.5 days; p=.43) or quantity (baseline, 1.6 ± .55 cigarettes; follow-up, 1.8 ± 1.1 cigarettes; p=.61).

No relationship was found between MPFC activity during exposure to antismoking messages and change in past month smoking frequency (p=.67) or quantity (p=.71) from baseline to follow-up. Urge to use e-cigarettes decreased across time points (F(27)=3.52, p=.044). Intent to use e-cigarettes did not change across time points (F(12)=2.42, p=.13; only measured in ever e-cigarette users), although there was a decrease in intent to use e-cigarettes from baseline to follow-up (p=.04).

DISCUSSION

This study used fMRI to test relationships between drinking behavior and neural responses to drinking cues and antidrinking messages among young adults who binge drink, and to explore responses to smoking cues and antismoking messages. Findings provide an estimate of the impact of antidrinking messages on neural drinking cue-reactivity and indicate that young adults with greater past month drinking were more resistant to the impact of antidrinking messages on neural drinking cue-reactivity. Importantly, the neural response to antidrinking messages was related to change in future drinking behavior.

First, we found that VS activity was higher for drinking versus neutral cues, consistent with reward-related drug cue-reactivity broadly26 and alcohol cue-reactivity25. Across many fMRI studies, VS activity indicates strong evidence for reward-related processing, with a probability of 0.942. Next, we found that VS activity was lower for drinking cues paired with antidrinking messages than for drinking cues alone, suggesting a decrease in reward-related cue-reactivity, as hypothesized. These findings suggest that antidrinking messages reduce drinking cue-reactivity. Neural drug cue-reactivity has been associated with poor treatment outcomes across studies of multiple substances of abuse43. For example, greater baseline drinking cue-reactivity predicted shorter time to relapse in individuals with AUD, with VS cue-reactivity as the strongest predictor44. Pharmacologic treatments for AUD such as naltrexone have been found to reduce neural cue reactivity45, and greater baseline VS cue-reactivity was found to predict better outcomes on naltrexone46, although overall findings of medication effects on drinking cue-reactivity are mixed43. Likewise, some initial studies suggest that psychosocial interventions may reduce neural drinking cue-reactivity43.

Our finding that VS activity was lower for drinking cues paired with antidrinking messages than for drinking cues suggests that antidrinking messages “devalued” drinking cues among young adults who binge drink. In line with this interpretation, we found that greater baseline past month drinking quantity was related to less of a decrease in VS activity for devalued drinking cues compared to drinking cues. This suggests that greater baseline drinking level was related to greater resistance to the devaluation of drinking cues by antidrinking messages. Greater resistance to devaluation might indicate a shift from goal-directed to habitual drinking despite negative consequences. In a prior study, alcohol cue-reactivity was higher in the VS for light social drinkers than heavy social drinkers, and higher in the dorsal striatum for heavy drinkers than light drinkers47. That study included adults (44 ± 8 years) who were much lighter (<1 drink/day) or much heavier (~5 drinks/day; 62% alcohol dependent) drinkers than the current study in young adults. A longer follow-up is needed to determine: (a) whether resistance to devaluation could distinguish young adults who will mature out of heavy drinking from those who will not; and (b) whether those who go on to alcohol dependence show a shift from ventral to dorsal striatal cue-reactivity. Although another fMRI study linked reward-related drinking cue-reactivity to prior drinking in young adults48, to our knowledge, ours is the first to relate prior drinking to the potential resistance to devaluation of drinking cues by antidrinking messages.

Another main finding was that MPFC activity during exposure to antidrinking messages was related to change in past month drinking frequency from baseline to one month follow-up. Although there was not an overall decrease in drinking frequency across time points, young adults who reported fewer past month drinking days at follow-up were those who had shown the greatest MPFC response to antidrinking messages during fMRI. A series of fMRI studies has demonstrated that MPFC activity during exposure to health messages predicts future health behavior beyond self-report, with most studies in smoking, but also in other health behaviors such as sunscreen use27, 28. MPFC activity in small groups has even been used to predict real-world impact of mass media antismoking campaigns at the population-level49–51. The MPFC has a central role in self- and value-related processing that has been established broadly across cognitive, affective and social domains52, 53. MPFC response to health messages is therefore thought to represent evaluation of message self-relevance54. Studies indicate that health messages which are more successful at engaging the MPFC are more effective in motivating change in health behavior51, and that individuals who show higher MPFC response to health messages are more likely to show related health behavior change55, 56. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test MPFC activity during exposure to antidrinking messages as a marker of future change in drinking behavior. A related fMRI study in young adults found that more compared to less effective antidrinking messages were associated with greater inter-subject correlation in the MPFC, suggesting common neural processing of more effective antidrinking messages in the MPFC57. Our results provide new evidence that MPFC response to antidrinking messages can predict changes in drinking behavior. This effect was not mediated by ratings of effectiveness of antidrinking messages, post-scan memory for antidrinking messages, or post- minus pre-scan intent to binge drink, supporting that MPFC activity predicts change in drinking beyond self-report. MPFC activity may therefore provide a measure of antidrinking message effectiveness for young adults.

Relatedly, the VS and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) have been identified by an fMRI meta-analysis to comprise a neural “valuation system” in which activity is considered to represent and scale with domain-general subjective value58. A recent study measured activity in these brain regions as young adults viewed antidrinking messages and were asked to think about why the messages were persuasive (relevant/strong) or not, as a proxy for subjective value56. Drinking-related peer conversations and drinking behavior were tracked for one month. Young adults who showed higher activity in the valuation system during antidrinking messages were less susceptible to future influence of pro-alcohol peer conversations on drinking behavior. Although both VS and VMPFC were tested, effects were driven by the VS. It has been argued that the VS may encode lower level reward processing, while the VMPFC may encode higher level calculated processing of behavioral value56. However, more work is needed to determine which components of the valuation system are most relevant in different conditions29. In an effort to explore the relevance of the VS and MPFC to the current task conditions, we performed several post-hoc tests. First, our “devaluation” analysis focused on drinking cue reactivity in the VS. However, post-hoc, we found that MPFC activity was lower for devalued drinking cues than drinking cues (p=.001), but this difference in MPFC activity did not correlate with baseline past month drinking (p>.05). Likewise, our persuasion analysis focused on MPFC response to antidrinking messages because this region has been implicated across studies of persuasive messaging29. Post-hoc, we found that VS response to antidrinking messages did not relate to future drinking (p>.05). Together, these findings are consistent with a role for the MPFC in value computation (e.g.60) and self-related processing that is relevant to both devaluation of drinking cues and to processing of antidrinking messages56.

Behaviorally, we found that past month drinking quantity decreased from baseline to one month follow-up. Among young adults who binge drink, antidrinking messages are a form of intervention. Findings may therefore reflect both implicit/instrumental-habitual changes in drinking in response to experimental manipulation including devaluation of drinking reward, and explicit/goal-oriented changes in drinking behavior among binge drinkers who were concerned about their drinking. Antidrinking messages were rated as effective during fMRI, and there was a decrease in the intent to binge drink and urge to drink across time points. A comparator group is needed to directly test intervention effects, rule-out regression to the mean, and isolate demand characteristics. Nevertheless, drinking quantity is considered to be a modifiable risk factor for multiple negative health outcomes including AUD. Furthermore, drinking quantity may be easier to modify among young adults than other drinking behaviors such as drinking frequency. For example, naltrexone was found to help heavy drinking young adults reduce drinks per drinking day and percentage of drinking days with estimated blood alcohol content above the legal limit of intoxication, but did not alter percent days heavy drinking or percent days abstinent in an 8-week treatment61.

Finally, we found that higher VS response to drinking cues was related to poorer post-scan memory for antidrinking messages. This is in line with an fMRI study in which higher VS activity as young adults viewed e-cigarette advertisements was related to poorer post-scan memory for e-cigarette health warnings presented on those advertisements62. However, in that study, VS response to drug cues was not compared to neutral cues, limiting inference that VS activity represented reward-related cue-reactivity. Our study builds on that work by including neutral cues, suggesting that higher reward-related drinking cue-reactivity in the VS was associated with poorer memory for antidrinking messages. This suggests that young adults who binge drink may not have attended to antidrinking messages. In the earlier study, fMRI eye tracking data indicated that young adults spent more time viewing rewarding advertising content and less time viewing warning labels. There is some evidence that health warnings can reduce substance cue-reactivity63, 64 and that message tailoring can increase attention to health messages to more effectively motivate behavior change55, 65, 66. Here, we tailored antidrinking messages to young adults by describing relevant social and health consequences and by using age-matched actors. More work is needed to determine whether additional tailoring might increase attention to antidrinking messages and better motivate behavior change.

This study additionally explored responses to smoking cues and antismoking messages, although only five participants were current (non-daily) smokers. Therefore, we may have recruited young adults concerned about their drinking but not their smoking. There were no changes in smoking over time, and no relationships were found between neural responses to smoking cues and antismoking messages and smoking behavior. Another concern is cross-reactivity by which smoking cues are associated with drinking among drinkers67. We indirectly examined cross-reactivity post-hoc and found no relationship between VS response to smoking cues and mean urge to drink (p>.05), however, urge to drink was only measured after drinking cues, and urge to smoke after smoking cues. Our findings should be expanded in a cross-over response design with adequately powered groups who differ systematically in their use of alcohol and tobacco68 and with assessment of drinking and smoking urge after each cue type. Another possibility is that antismoking messages may have enhanced the impact of antidrinking messages. Again, we examined this post-hoc and found no relationship between MPFC response to antismoking messages and changes in drinking (p>.05), therefore the ability to recruit executive control mechanisms generally does not appear to predict future drinking.

There were several additional methodological concerns. It is possible that the decrease in VS activity for devalued drinking cues versus drinking cues may be due in part to habituation to repeated presentation of drinking cues. However, our finding that the difference in VS activity related to prior drinking demonstrates that individual differences in devaluation are still identifiable despite potential habituation. Further, to estimate the contribution of habituation, we measured the effect size for the difference in VS activity between smoking cues and devalued smoking cues for never-smokers (d’=.40). This might be compared to the effect size for the difference in VS activity between drinking cues and devalued drinking cues (d’=.73) to estimate devaluation. Another study could include a neutral or no message condition to directly test the effect of repeated presentation of drinking cues. Additionally, given the small sample size, we were unable to correct for multiple comparisons for the correlations between VS activity and prior drinking frequency and quantity and between MPFC activity and future drinking frequency and quantity. Replication in a larger sample is necessary.

In conclusion, our findings help to characterize the relationship between drinking behavior and neural responses to drinking cues and antidrinking messages in young adults who binge drink. Drinking behaviors were related to both neural reward processing in the VS and executive control processes in the MPFC. More work is needed to determine whether functional connectivity between these brain regions is related to changes in drinking behavior. A longer follow-up is needed to determine whether these responses might distinguish young adults who will mature out of heavy drinking from those who will not. The current findings may help to inform interventions aimed to reduce alcohol use and reward among young adults.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Stephen Healy, Ann Agro, Karen Martin, “Voices by Trish,” and our participants. This study was funded by the Yale Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcoholism (grant number: P50AA012870) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number: K12DA00167). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. J Drug Issues 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SA, Mcgue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KC, Lowman C, Murphy S. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics 2008; 121 Suppl 4: S290–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey On Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19‑5068, NSDUH series H‑54). 2019; Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/.

- 5.Johnston LD, O’malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA, Monitoring The Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975– 2015: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merrill JE, Carey KB. Drinking over the lifespan: Focus on college ages. Alcohol Res 2016;38:103–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alchololism. Drinking levels defined. 2019; Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking.

- 8.Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Drinking in America: Myths, realities, and prevention policy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alchololism. The scope of the problem. Alcohol Res Health 2004/2005;23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics 2003;111:949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey On Alcohol And Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72(8): 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood - implications for substance-abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992; 112: 64–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White HR, Jackson K. Social and psychological influences on emerging adult drinking behavior. Alcohol Res Health, 2004–2005;28:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Allen HK, Vincent KB, Bugbee BA, O’grady KE. Drinking like an adult? Trajectories of alcohol use patterns before and after college graduation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016;40:583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Malley PM. Maturing out of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health 2004–2005;28:202–204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winick C Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bull Narc 1962; 14(1–7). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol 2009;118:360–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon D, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Pohl KM. Regional growth trajectories of cortical myelination in adolescents and young adults: Longitudinal validation and functional correlates. Brain Imaging Behav 2018. November 8. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9980-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young B, Lewis S, Katikireddi SV, Bauld L, Stead M, Angus K, Campbell M, Hilton S, Thomas J, Hinds K, Ashie A, Langley T. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption and harm: A systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53:302–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Reducing underage drinking. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogarth L, Balleine BW, Corbit LH, Killcross S. Associative learning mechanisms underpinning the transition from recreational drug use to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013;1282:12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickinson A, Wood N, Smith JW. Alcohol seeking by rats: Action or habit? Q J Exp Psychol B 2002;55:331–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez MF, Becker HC, Chandler LJ. Repeated episodes of chronic intermittent ethanol promote insensitivity to devaluation of the reinforcing effect of ethanol. Alcohol 2014;48:639–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker JM, Taylor JR. Habitual alcohol seeking: Modeling the transition from casual drinking to addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014;47:281–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chase HW, Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Hogarth L. The neural basis of drug stimulus processing and craving: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2011;70:785–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schacht JP, Anton RF, Myrick H. Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: A quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review. Addict Biol 2013;18:121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falk EB, Cascio CN, Coronel JC. Neural prediction of communication-relevant outcomes. Commun Methods Meas 2015;9:30–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falk EB, Berkman ET, Mann T, Harrison B, Lieberman MD. Predicting persuasion-induced behavior change from the brain. J Neurosci 2010;30:8421–8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falk E, Scholz C. Persuasion, influence, and value: Perspectives from communication and social neuroscience. Annu Rev Psychol 2018;69:329–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbin WR, Zalewski S, Leeman RF, Toll BA, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. In with the old and out with the new? A comparison of the old and new binge drinking standards. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38:2657–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knecht S, Drager B, Deppe M, Bobe L, Lohmann H, Floel A, Ringelstein EB, Henningsen H. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain 2000; 123 Pt 12: 2512–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson GS, Pusakulich RL, Ward JP, Hermann B. Handedness, footedness, and language laterality: Evidence from wada testing. Laterality 1998;3:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:1180–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ajzen I Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 2002;32:665–683. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN, International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual Technical report A-8. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billieux J, Khazaal Y, Oliveira S, De Timary P, Edel Y, Zebouni F, Zullino D, Van Der Linden M. The Geneva Appetitive Alcohol Pictures (GAAP): Development and preliminary validation. Eur Addict Res 2011;17:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert DG, Rabinovich NE, International Smoking Image Series, Version 1.2 Carbondale Integrative Neuroscience Laboratory, Department of Psychology, Southern Illinois University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khazaal Y, Zullino D, Billieux J. The Geneva Smoking Pictures: Development and preliminary validation. Eur Addict Res 2012;18:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alchololism. Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. NIH Publication No. 15–3770 2015 [cited 2015 Nov. 27]; Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/RethinkingDrinking/Rethinking_Drinking.pdf. 2015.

- 40.American Heart Association. Smoking: Do you really know the risks?; Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/QuitSmoking/QuittingSmoking/Smoking-Do-you-really-know-the-risks_UCM_322718_Article.jsp#.VliI6RCrT_9. 2015.

- 41.Truth Initiative. https://www.thetruth.com. 2016. [Accessed 07 August 2019].

- 42.Ariely D, Berns GS. Neuromarketing: The hope and hype of neuroimaging in business. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courtney KE, Schacht JP, Hutchison K, Roche DJ, Ray LA. Neural substrates of cue reactivity: Association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addict Biol 2016;21:3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinhard I, Lemenager T, Fauth-Buhler M, Hermann D, Hoffmann S, Heinz A, Kiefer F, Smolka MN, Wellek S, Mann K, Vollstadt-Klein S. A comparison of region-of-interest measures for extracting whole brain data using survival analysis in alcoholism as an example. J Neurosci Methods 2015;242:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Randall PK, Voronin K. Effect of naltrexone and ondansetron on alcohol cue-induced activation of the ventral striatum in alcohol-dependent people. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:466–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mann K, Vollstadt-Klein S, Reinhard I, Lemenager T, Fauth-Buhler M, Hermann D, Hoffmann S, Zimmermann US, Kiefer F, Heinz A, Smolka MN. Predicting naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients: The contribution of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38:2754–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vollstadt-Klein S, Wichert S, Rabinstein J, Buhler M, Klein O, Ende G, Hermann D, Mann K. Initial, habitual and compulsive alcohol use is characterized by a shift of cue processing from ventral to dorsal striatum. Addiction 2010;105:1741–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Courtney AL, Rapuano KM, Sargent JD, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Reward system activation in response to alcohol advertisements predicts college drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2018;79:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falk EB, O’donnell MB, Tompson S, Gonzalez R, Dal Cin S, Strecher V, Cummings KM, An L. Functional brain imaging predicts public health campaign success. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2016;11:204–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang AL, Ruparel K, Loughead JW, Strasser AA, Blady SJ, Lynch KG, Romer D, Cappella JN, Lerman C, Langleben DD. Content matters: Neuroimaging investigation of brain and behavioral impact of televised anti-tobacco public service announcements. J Neurosci 2013;33:7420–7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Falk EB, Berkman ET, Lieberman MD. From neural responses to population behavior: Neural focus group predicts population-level media effects. Psychol Sci 2012;23:439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmitz TW, Johnson SC. Relevance to self: A brief review and framework of neural systems underlying appraisal. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2007;31:585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Northoff G, Heinzel A, De Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain-a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage 2006;31:440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vezich IS, Katzman PL, Ames DL, Falk EB, Lieberman MD. Modulating the neural bases of persuasion: Why/how, gain/loss, and users/non-users. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2017;12:283–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chua HF, Ho SS, Jasinska AJ, Polk TA, Welsh RC, Liberzon I, Strecher VJ. Self-related neural response to tailored smoking-cessation messages predicts quitting. Nat Neurosci 2011;14:426–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scholz C, Dore BP, Cooper N, Falk EB. Neural valuation of antidrinking campaigns and risky peer influence in daily life. Health Psychol 2019;38:658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imhof MA, Schmalzle R, Renner B, Schupp HT. How real-life health messages engage our brains: Shared processing of effective anti-alcohol videos. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2017;12:1188–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartra O, Mcguire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. Neuroimage 2013;76:412–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarkoni T, Poldrack RA, Nichols TE, Van Essen DC, Wager TD. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat Methods 2011;8:665–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the VMPFC valuation system. Science 2009;324:646–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Malley SS, Corbin WR, Leeman RF, Demartini KS, Fucito LM, Ikomi J, Romano DM, Wu R, Toll BA, Sher KJ, Gueorguieva R, Kranzler HR. Reduction of alcohol drinking in young adults by naltrexone: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:e207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garrison KA, O’Malley SS, Gueorguieva R, Krishnan-Sarin S. A fMRI study on the impact of advertising for flavored e-cigarettes on susceptible young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;186:233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenblatt DH, Summerell P, Ng A, Dixon H, Murawski C, Wakefield M, Bode S. Food product health warnings promote dietary self-control through reductions in neural signals indexing food cue reactivity. Neuroimage Clin 2018;18:702–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang AL, Romer D, Elman I, Turetsky BI, Gur RC, Langleben DD. Emotional graphic cigarette warning labels reduce the electrophysiological brain response to smoking cues. Addict Biol 2015;20:368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Falk EB, Berkman ET, Whalen D, Lieberman MD. Neural activity during health messaging predicts reductions in smoking above and beyond self-report. Health Psychol 2011;30:177–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bryan CJ, Yeager DS, Hinojosa CP, Chabot A, Bergen H, Kawamura M, Steubing F. Harnessing adolescent values to motivate healthier eating. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016;113:10830–10835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Drobes DJ. Cue reactivity in alcohol and tobacco dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002;26:1928–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stritzke WG, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR. Assessment of substance cue reactivity: Advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychol Addict Behav 2004;18:148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.