Abstract

Objective:

Assess the effect of healthy or unhealthy food brands on consumer ratings of a food’s perceived healthfulness, caloric content, and estimated price.

Methods:

Using a crossover design, thirty-five adults aged 18-25 years scored a variety of healthy and unhealthy foods paired with healthy or unhealthy brands or with no brand present on their healthfulness, caloric content and estimated price. For each outcome measure ANOVA was used to evaluate the effect of brand condition on healthy and unhealthy foods.

Results:

Pairing an unhealthy food with a healthy brand led to increased ratings of healthfulness (p < 0.001), decreased estimates of caloric content (p< 0.001), and higher price (p< 0.001). Pairing a healthy food with an unhealthy brand led to decreased ratings of healthfulness (p< 0.001), caloric content (p< 0.001), and price (p< 0.001).

Conclusions and Implications:

These findings extend previous research showing that brands themselves may influence perceptions of food products. Future studies are needed to understand the implications of pairing healthy foods with unhealthy brands on actual food intake.

Keywords: Food Branding, Health Perception, Calorie Estimation, Price Estimation

INTRODUCTION

One of the major goals of marketing campaigns is to establish brand loyalty within a consumer base.1 Brand loyalty involves developing a unique, emotional attachment to a company through the use of names, symbols, logos, characters, and slogans in an attempt to increase product purchases over the consumers’ lifetime.2 Ultimately, brands become a symbol of product quality and help consumers simplify choices by reducing risk and engendering trust.3,4 Brands play a crucial role in marketing strategies and can often significantly influence the marketing’s effectiveness.3 In the food marketplace, efforts to build brand loyalty are ubiquitous and have been shown to impact food preferences in children as young as 3 years old.5 These aggressive and pervasive marketing campaigns have been directly implicated as a contributing factor to the obesity epidemic.6 Brands provide companies a rapid way to convey information on product content and quality7,8 and previous studies have shown that brands and the accompanying packaging can influence the perception of a food’s healthfulness and caloric content.9 Furthermore, brands have been shown to alter the perceived liking of food products and ultimately influence intake of those products.10,11 However, as brands are tied to the general messaging and products of their product lines 12 if a brand has an unhealthy image it may be difficult for them to market healthy products successfully.

Food companies have employed several strategies to promote a healthier image in response to their increasingly negative public perception.13 One strategy has been for companies to launch or acquire new brands to present themselves as healthy alternatives to existing products.14 These “better-for-you” brands often tout “healthy,” “natural,” or “organic” labels, but vary in nutritional quality. For instance, in 1 analysis of 354 child-targeted foods, researchers identified that 65% of “better-for-you” products contained high levels of sugar, fat, and sodium.15 In another review of 58 packaged foods with “healthy” front-of-package claims, 84% were considered unhealthful because products “did not meet 1 or more nutrient criteria for total sugars, fat, saturated fat, sodium, or fiber”.16 These misleading marketing campaigns have drawn the attention of researchers, consumers, policymakers, and regulatory agencies. For example, in 2015, the FDA sent a warning letter to KIND® for label violations including the use of terms such as “healthy” and “low fat” on a wide range of their products.17 KIND LLC, in turn, has publicly displayed select items from their competitors’ online in attempts to highlight the high amounts of sugars and sweeteners found in products that are marketed as “healthy”.18

The emergence of brands perceived as “healthy” and “unhealthy” has left consumers with an interesting challenge. To assess how healthy an overall product might be, consumers must reconcile their perception of the healthfulness of a brand with their perception of the healthfulness of a food.19 For example, one study demonstrated that participants with higher restrained eating scores consumed more cookies if they were presented with a “healthy” brand, Kashi®, than when they were presented with an “unhealthy” brand, Nabisco®. 11 These results highlight that both product brands may serve as a possible health cues. Of interest is that the brand may serve as a healthy cue even on an “unhealthy” product such as cookies. Since the cue brand and food cues are incongruent an individual may have more difficulty assessing the actual health aspects of the product. Thus, the way in which food companies market their brands can complicate the task of making healthful dietary choices.

While there is some evidence to suggest that brand perception may influence intake of the product, it is not clear if these brand cues generally influence perception of a food’s overall healthfulness, estimates of caloric content or more practical outcomes such as estimated product cost. Additionally, it is unclear if these effects are only apparent within nutritionally poor foods using brands perceived as healthy, as describe in the examples above, or if it is apparent across a variety of healthy and unhealthy food and brand pairings. Therefore, the primary aim of this preliminary study was to assess if brands perceived as healthy or unhealthy influence the perception of a variety of foods classified as healthy or unhealthy. By mainpulating brand logos, this study sought to evaluate changes in participant ratings of food products’ perceived healthfulness, perceived caloric content, and estimated price. Broadly, it was hypothesized that incongruent pairings (i.e., a healthy brand with an unhealthy food) would alter participants’ perception of food products. Specifically, it was hypothesized that unhealthy brands would reduce the perceived healthfulness and estimated price of healthy foods. It was also hypothesized that unhealthy brands would increase the perceived caloric content of healthy foods. Conversely, it was hypothesized that healthy brands would increase the perceived healthfulness and estimated price of unhealthy foods while decreasing the perceived caloric content.

METHODS

Selection and Development of the Food and Brand Stimuli

To select foods and brands for a product evaluation task, a questionnaire was developed and administered using Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk).20 Mechanical Turk is a crowdsourcing website owned by Amazon that can be used to recruit remotely located individuals, in this case throughout the United States, to perform discrete on-demand tasks, such as questionnaires. The questionnaire used was adapted for study purposes based on a similar questionnaire developed by Cavanagh et al.11 Fifty respondents were asked to rate the healthfulness of 28 foods and 45 brands on a Likert scale ranging from 1-10. All 50 individuals lived in the United States, were between 18-25 years of age, and had a history of providing high quality responses in past online studies (HIT Approval Rate greater than 95%). The 12 foods with the highest healthfulness rating and the 12 foods with the lowest healthfulness ratings, based on the Mturk participant ratings, were categorized as healthy and unhealthy foods, respectively. Similarly, the 4 brands with the highest healthfulness ratings and the 4 brands with the lowest healthfulness ratings were categorized as healthy and unhealthy brands, respectively. The foods and brands that were selected from this task, as well as the healthfulness ratings they received, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Foods and brands selected from pilot stimulus survey with mean healthfulness ratings.

| Healthy Foods | Perceived Healthfulness Rating |

|---|---|

| Fruit cup | 9.0 |

| Oatmeal | 8.4 |

| Chicken salad | 8.2 |

| Assorted nuts | 8.2 |

| Apricots | 7.4 |

| Raisins | 7.4 |

| Apples and peanut butter | 7.3 |

| Vanilla yogurt and fruit parfait | 7.1 |

| Chicken noodle soup | 6.8 |

| Granola bar with nuts | 6.8 |

| Strawberry yogurt | 6.8 |

| Unhealthy Foods | Perceived Healthfulness Rating |

| Bacon and egg sandwich | 3.6 |

| Mac and cheese | 3.3 |

| Waffles | 3.3 |

| Pepperoni pizza | 2.9 |

| Chicken nuggets | 2.7 |

| Vanilla ice cream | 2.5 |

| Pop tart | 2.0 |

| Brownie | 2.0 |

| Chocolate chip cookies | 1.9 |

| Chocolate cake | 1.9 |

| Chocolate cookie | 1.8 |

| Donuts | 1.7 |

| Healthy Brands | Perceived Healthfulness Rating |

| Kashi® | 7.4 |

| Healthy Choice® | 7.4 |

| Quaker® | 7.3 |

| Nature Valley® | 7.2 |

| Unealthy Brands | Perceived Healthfulness Rating |

| Nabisco® | 4.0 |

| Kraft® | 3.8 |

| Pillsbury® | 2.6 |

| Hostess® | 1.8 |

Results of an online questionnaire administered using Amazon Mechanical Turk.20 Fifty respondents rated the healthfulness of 28 foods and 45 brands on a scale ranging from 1-10. The 12 foods with the highest healthfulness rating and the 12 foods with the lowest healthfulness ratings (displayed above alongside their mean score) were selected for presentation in the larger study. The 4 brands with the highest healthfulness ratings and the 4 brands with the lowest healthfulness ratings (displayed above alongside their mean score) were selected for the larger study.

Participants and Recruitment

From February to April 2018, 35 young adults (N = 35; 9 male) aged 18-25 years (mean ± SD = 20.7 ± 1.3 years) were recruited through posted flyers and online list-serves. Thirty-three participants were undergraduate students at Dartmouth College and 2 participants were members of the nearby Upper Valley community. All participants were fluent in English and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Each individual provided informed consent, and each received $30 for their time. Dartmouth’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved all study procedures.

Study Design

Participants were scheduled for a single visit between the hours of 9:00 am and 6:30 pm. Upon arriving at the lab, each participant was directed to a laptop computer where they completed a series of questionnaires and tasks. The questionnaires were implemented using Qualtrics Survey Software21. As part of the questionnaires, each participant rated how hungry they felt on a standard visual analog scale in order to control for variability in participants’ level of hunger. As part of this larger set of questionnaire and tasks participants completed a product evaluation task in which healthy and unhealthy brands were paired with healthy or unhealthy foods. Given the study’s small sample size, questionnaire results were not used to correlate participant characteristics with study outcomes. Therefore, they are not reported in this paper. However, the full list of questionnaires completed by participants is provided as Supplemental Materials.

Product Evaluation Task

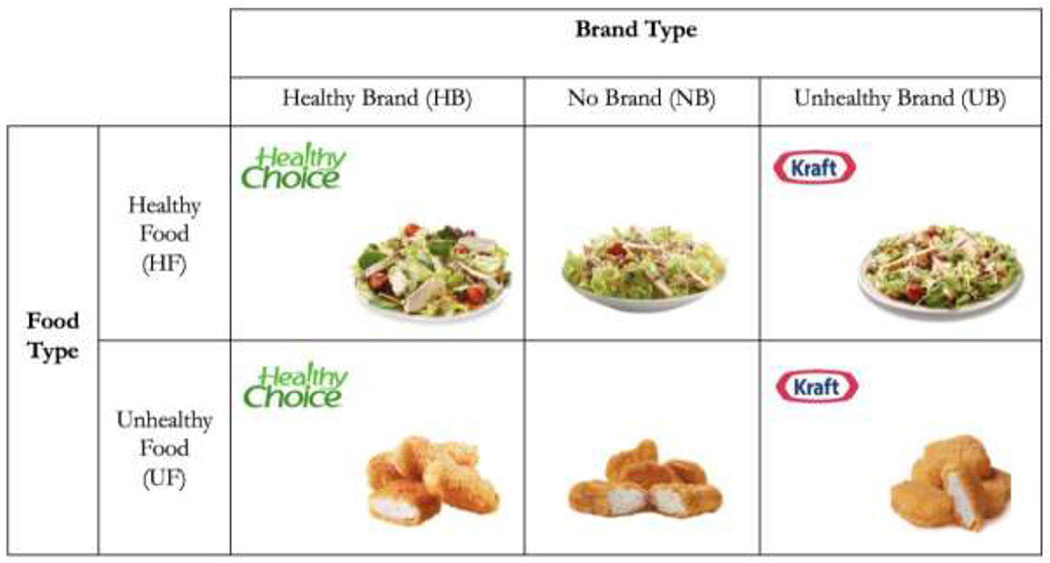

During the product evaluation task, participants were taken into a booth that consisted of an enclosed desk, a computer keyboard, and a 25” computer desktop monitor. A researcher explained that the task would last 30-45 minutes during which the participants would evaluate “newly released” food products. For the display of the food products, 3 similar but distinct imges of each of the 12 healthy and 12 unhealthy foods, identified by the Mturk questionnaire, were obtained. For each food, 1 image was presented without a brand image, 1 image was randomly paired with 1 of the 4 brands categorized as healthy, and 1 image was randomly paired with 1 of the 4 brands categorized as unhealthy. Therefore, participants were presented with a total of 72 food product images (24 foods x 3 brand conditions). Figure 1 provides visual examples of the food product images.

Figure 1.

Examples of stimuli presented under the 3 conditions in the product evaluation task. Brand and Foods were determined for the results of an online questionnaire administered using Amazon Mechanical Turk.20 Fifty respondents rated the healthfulness of 28 foods and 45 brands on a scale ranging from 1-10. The 12 foods with the highest healthfulness rating and the 12 foods with the lowest healthfulness ratings were used for this task. The 4 brands with the highest healthfulness ratings and the 4 brands with the lowest healthfulness ratings were used for this task. Thirty-five young adults (N = 35; 9 male) viewed 72 food-brand product combinations. They responded to 3 questions for each product including: 1) On a scale ranging from 1-10, how healthy do you think this product is? 2) On a scale ranging from low-high calorie, how caloric is this product? and 3) On a scale ranging from $0-$20, how much does this product cost?

During the task, all images were presented using the iMotions software program22 (iMotions, Copenhagen, Denmark). Each trial consisted of a fixation cross (1 sec), exposure to a product image (6 sec), and a screen in which 4 questions were answered using sliding scales (unlimited time allowed). The food product images were presented in a randomized order throughout the task and the 4 questions were presented in a randomized order within each trial. The 4 questions included: 1) On a scale ranging from 1-10, how healthy do you think this product is?, 2) On a scale ranging from low-high calorie, how caloric is this product?, 3) On a scale ranging from $0-$20, how much does this product cost?, 4) On a scale ranging from 1-10, how much do you want to eat this product right now?

To encourage continued participant engagement during the trials, the experimenter alerted them when they were 25%, 50%, and 75% of the way through the task. The participants were also told that their ratings from the question, “how much do you want to eat this product right now?” would result in 1 of the products being given to them at the end of the task. Once the participants had completed the task, their desire ratings for 2 of the presented products (unbranded Quaker® cookie and unbranded Kashi® bar) were compared. Each participant then received their more highly rated product.

Data Analysis

A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze each of the 3 rating dimensions (perceived healthfulness, perceived caloric content, and estimated product price). Food Type (healthy, unhealthy) and Brand Type (no brand, healthy brand, unhealthy brand) were modeled as independent variables. For all analyses, the response data was checked for the following assumptions: 1) outliers, as assessed by studentized residuals ±3 standard deviations23 and 2) sphericity, as assessed by Mauchly’s test of sphericity.24 Importantly, Mauchly’s test of sphericity assesses whether the variances of the differences between all related conditions are equal. Should there be a violation of sphericity, an adjustment to the degrees of freedom must be made to reduce the chance of a Type 1 error. In this study, if the sphericity assumption was not met, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction25 was applied. The statistical tests for each model were corrected for multiple comparison using a Bonferroni correction. All p-values were multiplied by the number of comparisons made within the model to yield Bonferroni-corrected p-values, which are reported in the results of this paper. For all relationships tested, a p-value threshold of ≤ 0.05 was used to determine significance. All data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (2017, IBM Corp.,Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Overall means for each food-brand pair and the main effects and interaction results of each ANOVA are summarized in Table 2. All ANOVA post-hoc comparison results are reported and visualized in Figure 2. For visualization purposes, ratings have been standardized to the unbranded condition mean score for each food type. This was done by subtracting the mean rating value of the unbranded image from the healthy- and unhealthy-branded images in each rating category. Therefore, these figures visualize the relative change in score in comparison to the unbranded food image for that food type. No values were flagged as outliers in the response data. The ANOVA results for perceived healthfulness of the foods indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the 2-way interaction (χ2(2) = 6.45, p = 0.04). Therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to all tests.

Table 2.

Summary of ratings and repeated measures ANOVA results for outcome measures

| Healthfulness | Caloric Content | Price ($) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | ||||

| Healthy Food | ||||||

| No Brand | 7.30 ± 0.18 | 4.40 ± 0.17 | 2.60 ± 0.08 | |||

| Healthy Brand | 7.30 ± 0.18 | 4.31 ± 0.17 | 2.78 ± 0.10 | |||

| Unhealthy Brand | 6.31 ± 0.22 | 4.99 ± 0.17 | 2.51 ± 0.09 | |||

| Unhealthy Food | ||||||

| No Brand | 2.70 ± 0.10 | 7.73 ± 0.17 | 2.34 ± 0.07 | |||

| Healthy Brand | 3.50 ± 0.13 | 6.85 ± 0.18 | 2.72 ± 0.10 | |||

| Unhealthy Brand | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 7.81 ± 0.15 | 2.34 ± 0.07 | |||

| ANOVA Results | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value |

| Food Type | 38.86 | <0.001 | 194.82 | <0.001 | 18.55 | <0.001 |

| Brand Condition | 50.48 | <0.001 | 35.92 | <0.001 | 22.28 | <0.001 |

| INT Food × Brand | 23.17 | <0.001 | 22.44 | <0.001 | 14.08 | <0.001 |

Aggregate ratings of three questions from thirty-five young adults (N = 35; 9 male) for 72 food-brand product combinations. The questions for each product were: 1) On a scale ranging from 1-10, how healthy do you think this product is? 2) On a scale ranging from low-high calorie, how caloric is this product? and 3) On a scale ranging from $0-$20, how much does this product cost? ANOVA results computed using a 2x3 repeated measures ANOVA with food type and brand type as factors for each outcome (healthfulness, caloric content, and price). For all relationships tested, a Bonferroni corrected p-value ≤ 0.05 was used to determine significance. INT= interaction.

Figure 2.

Changes in ratings for each outcome variable (healthfulness, caloric content, and price). Ratings were obtained from 35 young adults (N = 35; 9 male) who viewed 72 food-brand product combinations. They responded to 3 questions for each product including: 1) On a scale ranging from 1-10, how healthy do you think this product is? 2) On a scale ranging from low-high calorie, how caloric is this product? and 3) On a scale ranging from $0-$20, how much does this product cost? Ratings have been standardized to the no brand food image for each category by subtracting the mean rating value of the no brand images from the healthy and unhealthy branded images. Therefore, changes in score reflect a relative change in comparison to the no brand food image for that food type. Bonferroni corrected post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed when healthy foods were paired with unhealthy brands, they had lower healthfulness ratings than when paired with healthy brands (M±SE = 0.99±0.12; p< 0.001) or no brand (M±SE = 0.99±0.14; p< 0.001); had higher caloric estimation compared to pairing with healthy brands (MΔ±SE = 0.67±0.12; p< 0.001) or no brand (0.58±0.11; p< 0.001); and had a lower price estimate than when paired with healthy brands (MΔ±SE = 0.26±0.05; p< 0.001). When healthy foods were paired with healthy brands, they had higher price estimates than when paired with no brand (0.17±0.06; p= 0.01). When unhealthy foods were paired with unhealthy brands, they had lower healthfulness ratings than when paired with healthy brands (MΔ±SE = 1.00±0.14; p<0.001) or no brand (MΔ±SE = 0.20±0.06; p=0.006); had higher caloric estimates than when paired with healthy brands (MΔ±SE = 0.96±0.14; p< 0.001); and had lower price estimates than when paired with healthy brands (MΔ±SE = 0.38±0.06; p< 0.001). When unhealthy foods were paired with healthy brands, healthiness rating were higher than when paired no brand (M±SE = 0.80±0.15; p< 0.001); had lower caloric estimates than when paired with no brand (0.87±0.13; p< 0.001); and had higher price estimates than when paired with no brand (0.38±0.07; p< 0.001). The # symbol signifies a significant (p<.05) difference from the unbranded image for that food type. The * symbol signifies significant (p<.05) difference between indicated groups.

The ANOVA demonstrated a statistically significant partial main effect of healthfulness ratings showing that regardless of brand pairing, healthy foods had higher healthfulness ratings than unhealthy foods (M±SE = 4.06±0.22; p< 0.001). For significant post-hoc pairwise comparisons, a 13.6% decrease was observed in the perceived healthfulness of the healthy food when paired with the unhealthy brand compared to being paired with the healthy branded or unbranded images. Additionally, a 29.6% increase in the perceived healthfulness of the unhealthy food was observed when paired with the healthy brand compared to being paired with the unhealthy brand and a 40.0% increase compared to the unbranded images.

The ANOVA demonstrated a statistically significant partial main effect of caloric estimations showing that unhealthy foods were perceived to have higher caloric ratings than healthy foods (MΔ±SE = 2.89±0.20; p< 0.001). For significant post-hoc pairwise comparisons, a 15.8% increase in the perceived caloric content of a healthy food when paired with an unhealthy brand compared to paring with a healthy brand and a 13.4% increase compared no brand. There was a 12.3% decrease in the perceived caloric content of the unhealthy food when paired with the healthy brand compared to being paired with the unhealthy brand and a 11.3% decrease compared to no brand.

The ANOVA demonstrated a statistically significant partial main effect of price estimations showing that healthy foods were perceived to have a higher price than unhealthy foods (MΔ±SE = 0.16±0.03; p< 0.001). For significant post-hoc pairwise comparisons, there was a 10.8% increase in the estimated cost of the healthy food when paired with the healthy brand compared to being paired with the unhealthy brand and a 6.9% increase compared to the unbranded images. For healthy foods paired with an unhealthy brand compared to unbranded images there was a 3.4% decrease in estimated cost. For unhealthy foods there was a 16.2% increase in estimated cost when paired with a healthy brand compared to being paired with an unhealthy brand or no brand. The pairing of the healthy brand with an unhealthy food was able to increase the estimated cost to nearly that of a healthy food paired with a healthy brand (mean price estimates of $2.72 and $2.78 respectively). The addition of the healthy brand led to approximately a $0.21 increase in the healthy food group and a $0.38 increase in the unhealthy food group compared to pairings with unhealthy food brands.

DISCUSSION

The data from this study provide preliminary evidence suggesting that consumers may perceive products as healthier, lower in calories, and justifiably higher in cost compared to other existing options based on the healthiness of the brand used to market it. This study extends prior research that has primarily focused on front-of-package cues.19 Additionally, the within-subjects design allowed for better control over variation in response that may have been attributed to between-subjects factors such as gender, dieting history, self-control, impulsivity, or mood fluctuations. 10, 11 Overall, the results of this preliminary study demonstrate that incongruent parings of healthy and unhealthy foods and brands cause the largest shift in product perception. Due to the bidirectional nature of this phenomenon, it may be aptly termed the “food brand dissonance effect”. These findings generally have potential relevance to health behaviors, as previous studies have shown that perception of a product’s healthfulness is linked to actual intake of the product.11

The results of this study show that incongruent pairings of foods and brands were not sufficiently strong enough to cause a complete shift in the perception foods healthiness (i.e. an unhealthy food being perceived as healthy). However, the shift in perceived healthfulness and caloric estimation still represent a significant change that could provide the product a meaningful advantage in comparison to other similar products. The reduction in the caloric estimation for the unhealthy foods when paired with healthy brands may be particularly problematic from a health perspective as it may serve as an indicator to disinhibit consumers’ consumption of the product.26 It is possible that a change in caloric estimation could affect a consumer’s initial product choice particularly when a variety of high- and low-calorie options are concurrently available.

Contrary to the authors’ incongruency hypothesis, the paring of both healthy and unhealthy foods with a healthy brand increased estimated cost of both categories of product. In fact, the pairing of the healthy brand with an unhealthy food was able to increase the estimated cost to nearly that of a healthy food paired with a healthy brand. This finding has potential ramifications for consumers as brands that are perceived as healthy may take advantage of this phenomenon and charge consumers more for products simply because of the brands association with health rather than actual health aspects of the product. The pairing of a healthy food with an unhealthy brand led to a significant drop in consumers estimation of price. This may have implications for brands attempting to add healthier products to product portfolios as consumers may expect lower price points and therefore may be unwilling to pay higher prices for “healthier” products from these companies.

Limitations

While the results of this study are promising, there are several important limitations to consider. First, previous research has noted differences in food perceptions by those who self-identify as healthy and unhealthy eaters, as well as those who are considered restrained and unrestrained eaters.10,27 However, because of the preliminary nature of this study and its small sample size, it was not possible to stratify and examine differences in the brand-induced perception effects among these groups. Additionally, the population tested was primarily undergraduate college students, therefore, these results are not generalizable Another limitation is that a limited set of food-brand pairings were used, and the food image variations selected for the task were not evaluated prior to use in the task. While this reduced the burden on the participants it is possible that specific food-brand pairings may have driven the observed effects. A final limitation of the study is that products were classified as “healthy” based on a set of 50 consumers’ perceptions and therefore results may vary when using defined cut offs such as the FDA’s definition of healthy rather than consumer perception.28

Implications for Research and Practice

The data from this study provide preliminary evidence suggesting that consumers may perceive products as healthier, lower in calories, and justifiably higher in cost compared to other existing options based on their perception of the brand used to market it. The results of this study also provide initial evidence that incongruently branding a food product leads to the largest shift in consumer perception. In employing incongruent branding techniques, companies stand to exploit consumers – both by making the marketplace more difficult to navigate and by charging higher costs. As brands serve as cues for product health and quality3,4 it is vital that they are used appropriately in the marketplace to indicate these messages to the consumer. Future studies are needed to replicate these preliminary results and assess their generalizability or examine the effects in more diverse populations. Future studies may also benefit by conducting more granular analysis of specific pairing of foods and brands or examining products differencing in sodium, fat, sugar, etc. Further studies are also needed to understand the implications of pairing healthy foods with unhealthy brands on purchasing behavior under real world conditions and for their effect on actual food intake.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to all those who participated in this project. We thank Carole Rodet for her help with data collection and project management; and John Brand, Jennifer Emond, and Reina Kato Lansigan for their valuable contributions to the study design and analyses. Financial support for this study was provided by the Kaminsky Family Fund and by NIH through a NIDA postdoctoral fellowship (T32DA037202, PI: Alan J. Budney) awarded to TDM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ghodeswar BM. Building brand identity in competitive markets: a conceptual model. J Prod Brand Management. 2008;Volume 17(Issue 1 ):4–12. doi: 10.1108/10610420810856468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connor SM. Food-Related Advertising on Preschool Television: Building Brand Recognition in Young Viewers. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1478–1485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller K, Lehmann DR. Brands and Branding: Research Findings and Future Priorities. Market Sci. 2006;25(6):740–759. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1050.0153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri A, Holbrook MB. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J Marketing. 2001;65(2):81–93. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson TN, Borzekowski DL, Matheson DM, Kraemer HC. Effects of Fast Food Branding on Young Children’s Taste Preferences. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2007;161(8):792–797. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):404. doi: 10.1037/a0014399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park WC, Jaworski BJ, MacInnis DJ. Strategic Brand Concept-Image Management. J Marketing. 1986;50(4):135–145. doi: 10.1177/002224298605000401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbig P, Milewicz J. The relationship of reputation and credibility to brand success. J Consum Mark. 1993;Volume 10(Issue 3): 18–24. doi: 10.1108/eum0000000002601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandon P How Package Design and Packaged-Based Marketing Claims Lead to Overeating. Ssrn Electron J. 2012. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2083618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavanagh KV, Kruja B, Forested CA. The effect of brand and caloric information on flavor perception and food consumption in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Appetite. 2014;82:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanagh KV, Forested CA. The effect of brand names on flavor perception and consumption in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Food Qual Prefer. 2013;28(2): 505–509. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Chernatony L, nald M. Creating Powerful Brands. 2003. doi: 10.4324/9780080476919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brownell KD, Waer KE. The Perils of Ignoring History: Big Tobacco Played Dirty and Millions Died. How Similar Is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitta DA, Katsanis L. Understanding brand equity for successful brand extension. J Consum Mark. 1995;Volume 12(Issue 4):51–64. doi: 10.1108/07363769510095306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott C Packaging Health: Examining “Better-for-You” Foods Targeted at Children. Can Public Policy. 2012;38(2):265–281. doi: 10.1353/cpp.2012.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sims J, Mikkelsen L, Gibson P, Warming E. Claiming Health: Front-of Package Labeling of Children’s Food. Prevention Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Correll WA. Warning Letter, KIND, LLC. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/kind-llc-03172015. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- 18.KIND. Sweeteners Uncovered. 2019. https://www.kindsnacks.com/media-center/press-releases/sweeteners-uncovered-pop-up.html. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- 19.Schuldt J, Schwarz N. The” organic” path to obesity? Organic claims influence calorie judgments and exercise recommendations. Judgment and Decision making. 2010;5(3):144. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44(1):1–23. doi: 10.3758/sl3428-011-0124-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snow J, Mann M. Qualtrics survey software: handbook for research professionals. 2013.

- 22.Lemos J Visual attention and emotional response detection and display system.

- 23.Aggarwal CC. Data Mining, The Textbook. 2015:237–263. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-14142-8_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauchly JW. Significance Test for Sphericity of a Normal n-Variate Distribution. Ann Math Statistics. 1940;ll(2):204–209. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177731915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhouse SW, Geisser S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika. 1959;24(2):95–112. doi: 10.1007/bf02289823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Provencher V, Polivy J, Herman PC. Perceived healthiness of food. If it’s healthy, you can eat more! Appetite. 2009;52(2):340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Provencher V, Jacob R. Impact of Perceived Healthiness of Food on Food Choices and Intake. Curr Obes Reports. 2016;5(1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0192-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Food and Drug Administration. Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products: Guidance for Industry. 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.