Abstract

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is an urgent public health threat due to rapidly increasing incidence and antibiotic resistance. In contrast with the trend of increasing resistance, clinical isolates that have reverted to susceptibility regularly appear, prompting questions about which pressures compete with antibiotics to shape gonococcal evolution. Here, we used genome-wide association to identify loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in the efflux pump mtrCDE operon as a mechanism of increased antibiotic susceptibility and demonstrate that these mutations are overrepresented in cervical relative to urethral isolates. This enrichment holds true for LOF mutations in another efflux pump, farAB, and in urogenitally-adapted versus typical N. meningitidis, providing evidence for a model in which expression of these pumps in the female urogenital tract incurs a fitness cost for pathogenic Neisseria. Overall, our findings highlight the impact of integrating microbial population genomics with host metadata and demonstrate how host environmental pressures can lead to increased antibiotic susceptibility.

Subject terms: Microbial genetics, Pathogens

Antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is rising, yet sometimes strains emerge that have reverted to susceptibility. Here, the authors find that selective pressures from the host may influence susceptibility through loss-of-function mutations in genes that encode for efflux pumps.

Introduction

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhea. Antibiotics have played a key role in shaping gonococcal evolution1–3, with N. gonorrhoeae gaining resistance to each of the first-line antibiotics used to treat it4–6. As N. gonorrhoeae is an obligate human pathogen, the mucosal niches it infects—most commonly including the urethra, cervix, pharynx, and rectum—must also influence its evolution7. The gonococcal phylogeny suggests the interaction of these factors, with an ancestral split between a drug-susceptible lineage circulating primarily in heterosexuals and a drug-resistant lineage circulating primarily in men who have sex with men3.

Despite the deeply concerning increase in antibiotic resistance reported in gonococcal populations globally8, some clinical isolates of N. gonorrhoeae have become more susceptible to antibiotics9,10. This unexpected phenomenon prompts questions about which environmental pressures could be drivers of increased susceptibility and the mechanisms by which suppression or reversion of resistance may occur. To address these questions, we analyzed the genomes of a global collection of clinical isolates together with patient demographic and clinical data to identify mutations associated with increased susceptibility and define the environments in which they appear. We find that loss-of-function mutations in the efflux pump component mtrC are significantly associated with both antibiotic susceptibility and cervical infections, demonstrating how antibiotic and mucosal niche selective pressures intersect. In support of a model in which efflux pump expression incurs a cost in this niche, we also observe enrichment of loss-of-function mutations in cervical isolates in another efflux pump in N. gonorrhoeae and in urogenitally-adapted N. meningitidis. Our findings demonstrate how shifts in environmental pressures experienced by pathogenic Neisseria can lead to loss of efflux pump function and suppression of antibiotic resistance.

Results

Unknown genetic loci influence antibiotic susceptibility

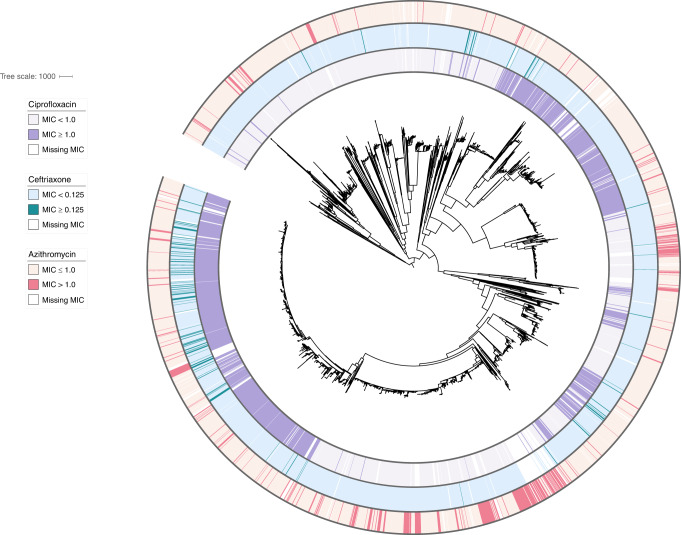

We first assessed how well variation in antibiotic resistance phenotype was captured by the presence and absence of known resistance markers. To do so, we assembled and examined a global dataset comprising the genomes and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 4852 isolates collected across 65 countries and 38 years (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). We modeled log-transformed MICs using multiple regression on a panel of experimentally characterized resistance markers for the three most clinically relevant antibiotics5,11,12 (Supplementary Data 1). This enabled us to make quantitative predictions of MIC based on known genotypic markers and to assess how well these markers predicted true MIC values. For the macrolide azithromycin, we observed that 434/4505 (9.63%) isolates had predicted MICs that deviated by two dilutions or more from their reported phenotypic values. The majority (59.4%) of these isolates had MICs that were lower than expected, indicative of increased susceptibility unexplained by the genetic determinants in our model. Overall MIC variance explained by known resistance mutations was relatively low (adjusted R2 = 0.667), in agreement with prior studies that employed whole-genome supervised learning algorithms to predict azithromycin resistance13. MIC variance explained by known resistance mutations was also low for ceftriaxone (adjusted R2 = 0.674) but higher for ciprofloxacin (adjusted R2 = 0.937), with 2.02% and 2.90% of strains, respectively, exhibiting two dilutions or lower reported MICs compared to predictions, similarly indicating unexplained susceptibility. The predictive modeling results, therefore, suggested unknown modifiers that promote susceptibility for multiple classes of antibiotics in N. gonorrhoeae.

Fig. 1. Population structure and susceptibility profile of N. gonorrhoeae global meta-analysis collection.

A midpoint rooted recombination-corrected maximum likelihood phylogeny of 4852 genomes based on 68697 SNPs (Supplementary Table 1) was annotated with binarized resistance (ciprofloxacin) or decreased susceptibility (azithromycin, ceftriaxone) values. Annotation rings are listed in order of ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, and azithromycin from innermost to outermost. For ciprofloxacin, MIC < 1 μg/ml is light purple, and MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml is dark purple. For ceftriaxone, MIC < 0.125 μg/ml is light blue, and MIC ≥ 0.125 μg/ml is dark blue. For azithromycin, MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml is light pink, and MIC > 1 μg/ml is dark pink. Branch length represents total number of substitutions after removal of predicted recombination.

GWAS identifies a susceptibility-associated variant in mtrC

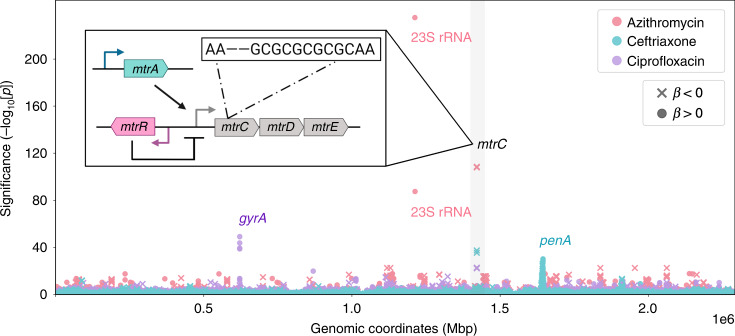

To identify novel antibiotic susceptibility loci in an unbiased manner, we conducted a bacterial genome-wide association study (GWAS). We used a linear mixed model framework to control for population structure, and we used unitigs constructed from genome assemblies to capture SNPs, indels, and accessory genome elements (see “Methods”)14–16. Unitigs are a flexible representation of the genetic variation across a dataset that are constructed using compacted de Bruijn graphs and have been previously applied as markers for microbial GWAS16. We performed a GWAS on the sequences of 4505 isolates with associated azithromycin MICs using a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 3.38 × 10−7. The linear mixed model adequately controlled for population structure (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the proportion of phenotypic MIC variance attributable to genotype (i.e., narrow-sense heritability) estimated by the linear mixed model was high (h2 = 0.97). In line with this, we observed highly significant unitigs with positive effect sizes corresponding to the known resistance substitutions C2611T and A2059G (E. coli numbering) in the 23S ribosomal RNA gene (Fig. 2)17. The next most significant variant was a unitig associated with increased susceptibility that mapped to mtrC (β, or effect size on the log2-transformed MIC scale = −2.82, 95% CI [−3.06, −2.57]; p-value = 2.81 × 10−108). Overexpression of the mtrCDE efflux pump operon has been shown to decrease gonococcal susceptibility to a range of hydrophobic acids and antimicrobial agents4,18, and conversely, knockout of the pump results in multi-drug hypersusceptibility19. To assess whether this mtrC variant was associated with increased susceptibility to other antibiotics, we performed GWAS for ceftriaxone (for which MICs were available from 4497 isolates) and for ciprofloxacin (4135 isolates). We recovered known ceftriaxone resistance mutations including recombination in the penA gene and ciprofloxacin resistance substitutions in DNA gyrase (gyrA). In agreement with the known pleiotropic effect of the MtrCDE efflux pump19, we observed the same mtrC unitig at genome-wide significance associated with increased susceptibility to both ceftriaxone (β = −1.18, 95% CI [−1.34, −1.02]; p-value = 2.00 × 10−44) and ciprofloxacin (β = −1.29, 95% CI [−1.54, −1.04]; p-value = 1.87 × 10−23) (Fig. 2). Across all three drugs, heritability estimates for this mtrC variant were comparable to that of prevalent major resistance determinants (azithromycin h2: 0.323; ceftriaxone h2: 0.208; ciprofloxacin h2: 0.155), indicating that unexplained susceptibility in our model could be partially addressed by the inclusion of this mutation.

Fig. 2. GWAS identifies a variant mapping to mtrC associated with increased susceptibility.

The Manhattan plot shows negative log10-transformed p-values (calculated using likelihood-ratio tests in the GWAS) for the association of unitigs with MICs to azithromycin (pink, n = 4505), ceftriaxone (blue, n = 4497), and ciprofloxacin (purple, n = 4135). The sign of the GWAS regression coefficient β (with positive indicating an association with increased resistance and negative indicating an association with increased susceptibility) is indicated by an X for β < 0 and a dot for β > 0. Labels indicate known influential resistance determinants, and the mtrC variant associated with increased susceptibility was highlighted in gray. A full list of the annotated significant unitigs for each antibiotic can be found in Supplementary Data 2. Inset: schematic of the mtr genetic regulon including structural genes mtrCDE, the activator mtrA, and the repressor mtrR. The approximate genomic location within mtrC and specific nucleotide change of the mtrC GWAS variant relative to the gonococcal NCCP11945 reference genome (i.e., a two base pair deletion in a ‘GC’ dinucleotide repeat) is shown.

Annotation of the mtrC unitig revealed that it represented a two base pair deletion in a ‘GC’ dinucleotide hexarepeat, leading to early termination of mtrC translation and probable loss of MtrCDE activity20 (Fig. 2 inset). We also checked whether the two base pair deletion would affect recognition by any of the gonococcal methylases21, but no methylase target motif sites mapped to the hexarepeat or its direct surrounding sequences. A laboratory-generated gonococcal mutant with a four base pair deletion in this same mtrC dinucleotide hexarepeat exhibited multi-drug susceptibility20, and clinical gonococcal isolates hypersensitive to erythromycin were shown to have mutations mapping to this locus22. To directly test the hypothesis that the two base pair deletion also contributed to increased susceptibility for the panel of antibiotics we examined, we complemented the mutation in a clinical isolate belonging to the multidrug-resistant lineage ST-190123 and observed significant increases in MICs for all three antibiotics, as predicted by the GWAS (Supplementary Table 2).

We searched for additional mtrC loss-of-function (LOF) mutations and found six clinical isolates with genomes encoding indels outside of the dinucleotide hexarepeat that also were associated with increased susceptibility (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Ten isolates that had acquired the two base pair deletion also have a two base pair insertion elsewhere in mtrC that restores the original coding frame, suggesting that loss of MtrC function may be reverted by further mutation or recombination (Supplementary Fig. 2A). In line with this, mtrC LOF mutations have emerged numerous times throughout the phylogeny (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicative of possible repeated losses of a dinucleotide in the hexarepeat region due to DNA polymerase slippage, which may occur at a higher rate than single nucleotide nonsense mutations24. In total, including all strains with mtrC frameshift mutations and excluding revertants, we identified 185 isolates (3.82%) that encoded a LOF allele of mtrC (Supplementary Table 3). Presence of the mtrC LOF mutation in isolates with known resistance markers was correlated with significantly reduced MICs (Supplementary Fig. 4), and inclusion of mtrC LOF mutations in our linear model increased adjusted R2 values (azithromycin: 0.667–0.704; ceftriaxone: 0.674–0.690; ciprofloxacin: 0.937–0.939), decreased the proportion of strains with unexplained susceptibility (azithromycin: 5.73%–3.88%; ceftriaxone: 2.02%–1.73%; ciprofloxacin: 2.90%–2.42%), and significantly improved model fit (p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 for all three antibiotics; Likelihood-ratio χ2 test for nested models). mtrC LOF strains were identified in 28 of the 66 countries surveyed and ranged in isolation date from 2002 to 2017. Because most strains in this dataset were collected within the last two decades, we also examined a dataset of strains collected in Denmark from 1928 to 2013 to understand the historical prevalence of mtrC LOF mutations25. We observed an additional 10 strains with the ‘GC’ two base pair deletion ranging in isolation date from 1951 to 2000, indicating that mtrC LOF strains have either repeatedly arisen or persistently circulated for decades. Our results demonstrate that a relatively common mechanism of gonococcal acquired antibiotic susceptibility is a two base pair deletion in mtrC and that such mutations are globally and temporally widespread.

Loss of MtrCDE pump is associated with cervical infection

The MtrCDE pump has been demonstrated to play a critical role in gonococcal survival in the presence of human neutrophils and in the female murine genital tract model of gonococcal infection, and overexpression of mtrCDE results in substantial fitness benefits for dealing with both antimicrobial and environmental pressures26–29. The relative frequency of the mtrC LOF mutations we observe (occurring in ~1 in every 25 isolates) thus seems unusual for a mutation predicted to be deleterious for human infection. mtrC LOF strains do not grow more or less quickly in vitro than mtrC wild-type strains, indicating that this mutation does not confer a simple fitness benefit due to reduced energetic cost22,26,30. Instead, we hypothesized that there are unique environments that select for non-functional efflux pump.

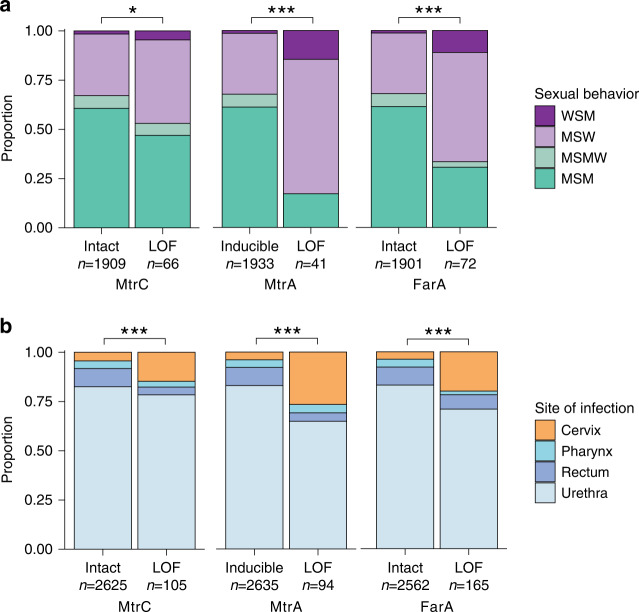

We aggregated patient-level metadata across included studies on sex partner preferences and anatomical site of infection. Sexual behavior and mtrC genotypic information was available for 1975 isolates from individual patients. There was a significant association between mtrC LOF and sexual behavior (p-value = 0.04021; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 4), and mtrC LOF occurred more often in isolates from men who have sex with women (MSW) (28/626, 4.47%) compared to isolates from men who have sex with men (MSM) (31/1189, 2.61%) (OR = 1.75, 95% CI [1.00–3.04], p-value = 0.037; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). To understand whether anatomical selective pressures contributed to this enrichment, we analyzed the site of infection and mtrC genotypic information available for 2730 isolates. mtrC LOF mutations were significantly associated with site of infection (p-value = 6.49 × 10−5; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and were overrepresented particularly in cervical isolates: 16 out of 129 (12.4%) cervical isolates contained an mtrC LOF mutation compared to 82 out of 2249 urethral isolates (3.65%; OR = 3.74, 95% CI [1.98–6.70], p-value = 4.71 × 10−5; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), 3 out of 106 pharyngeal isolates (2.83%; OR = 4.83, 95% CI [1.33–26.63], p-value = 0.00769; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), and 4 out of 246 rectal isolates (1.63%; OR = 8.52, 95% CI [2.67–35.787], p-value = 2.39 × 10−5; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 5). Because our meta-analysis collection comprised datasets potentially biased by preferential sampling for drug-resistant strains, we validated our epidemiological associations on a set of 2186 sequenced isolates, corresponding to all cultured isolates of N. gonorrhoeae in the state of Victoria, Australia in 201731. We again observed significant associations between mtrC LOF and sexual behavior (p-value = 0.0180; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) as well as the anatomical site of infection (p-value = 0.0256; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). mtrC LOF mutations were again overrepresented in cervical isolates: 9 out of 227 (3.96%) cervical isolates contained an mtrC LOF mutation compared to 15 out of 882 urethral isolates (1.70%; OR = 2.38, 95% CI [0.91–5.91], p-value = 0.0679; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), 3 out of 386 pharyngeal isolates (0.78%; OR = 5.26, 95% CI [1.29–30.51], p-value = 0.0117; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), and 7 out of 632 rectal isolates (1.11%; OR = 3.68, 95% CI [1.20–11.78], p-value = 0.0173; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). These results indicate that environmental pressures unique to female urogenital infection may select for loss of the primary gonococcal efflux pump resulting in broadly increased susceptibility to antibiotics and host-derived antimicrobial peptides.

Fig. 3. Gonococcal mtrC, mtrA, and farA LOF mutations are associated with cervical infection.

a Sexual behavior of patients infected with isolates with either intact or LOF alleles of mtrC (left), mtrA (middle), or farA (right). b Site of infection in patients infected with isolates with either intact or LOF alleles of mtrC (left), mtrA (middle), or farA (right). mtrA alleles were predicted as LOF only in the absence of other epistatic Mtr overexpression mutations. Statistical significance between genotype and patient metadata was assessed by two-sided Fisher’s exact test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Exact p-values from left to right for analyses in a were 0.04021, 1.81 × 10−11, 5.06 × 10−10 and for b were 6.49 × 10−5, 1.64 × 10−12, 1.78 × 10−12. WSM = women who have sex with men, MSW = men who have sex with women, MSMW = men who have sex with men and women, MSM = men who have sex with men.

mtrA LOF offers an additional level of adaptive regulation

The association of mtrC LOF mutations with cervical specimens suggests that other mutations that downregulate expression of the mtrCDE operon should also promote adaptation to the cervical niche. The MtrCDE efflux pump regulon comprises the MtrR repressor and the MtrA activator (Fig. 2 inset), the latter of which exists in two allelic forms: a wild-type functional gene capable of inducing mtrCDE expression and a variant rendered non-functional by an 11-bp deletion near the 5’ end of the gene32 (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Knocking out mtrA has a detrimental effect on fitness in the gonococcal mouse model, and epistatic mtrR mutations resulting in overexpression of mtrCDE compensate for this fitness defect by masking the effect of the mtrA knockout27. Prior work assessing the genomic diversity of mtrA in a set of 922 primarily male urethral specimens found only four isolates with the 11-bp deletion (0.43%)33, seemingly in agreement with the in vivo importance of mtrA. However, in our global meta-analysis dataset, 362/4842 isolates (7.48%) were predicted to be mtrA LOF, of which the majority (357/362, 98.6%) were due to the 11-bp deletion. Of the 4842 isolates, 268 (5.53%) had mtrA LOF mutations in non-mtrCDE overexpression backgrounds (as defined by the absence of known mtrR promoter or coding sequence mutations or mtrCDE mosaic alleles) and therefore not epistatically masked (Supplementary Table 8). We repeated our epidemiological associations on these mtrA LOF strains without concurrent overexpression mutations and observed highly significant associations with reported patient sexual behavior (p-value = 1.81 × 10−11; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and site of infection (p-value = 1.64 × 10−12; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 9–10). As with mtrC LOF mutations, mtrA LOF mutations were significantly overrepresented in cervical isolates: 25 out of 129 (19.4%) cervical isolates contained an mtrA LOF mutation compared to 61 out of 2248 urethral isolates (2.71%; OR = 8.60, 95% CI [4.96–14.57], p-value = 4.60 × 10−13; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), 4 out of 106 pharyngeal isolates (3.78%; OR = 6.09, 95% CI [2.00–24.93], p-value = 0.000240; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), and 4 out of 246 rectal isolates (1.63%; OR = 14.43, 95% CI [4.81–58.52], p-value = 3.00 × 10−9; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). In the Australian validation cohort31, the majority (81/85, 95.3%) of mtrA LOF strains had concurrent mtrCDE overexpression mutations, so it was not possible to test for these associations (Supplementary Table 11). In such genetic backgrounds where overexpression mutations mask the effect of mtrA LOF, mtrC LOF is the preferred method of efflux pump downregulation: the majority of mtrC LOF mutations in both the global dataset (174/180, 96.7%) and the Australian cohort (33/35, 94.3%) occurred in backgrounds with known mtr overexpression mutations (Supplementary Tables 12–13). Phylogenetic analysis showed that the distribution of mtrA LOF differed from that of mtrC LOF with fewer introductions but more sustained transmission and that the two mutations were largely non-overlapping (Supplementary Fig. 3); only four strains had both mtrA and mtrC LOF mutations. Our results indicate that multiple adaptive paths for MtrCDE efflux pump downregulation exist depending on genetic interactions with other concurrent mutations in the mtrCDE regulon.

FarAB efflux pump LOF is associated with cervical infection

The associations we observed in the mtrCDE regulon raised the question of the mechanism by which the cervical environment could select for pump downregulation. Recent work on Pseudomonas suggested one possible model: overexpression of homologous P. aeruginosa efflux pumps belonging to the same resistance/nodulation/cell division (RND) proton/substrate antiporter family as MtrCDE results in a fitness cost due to increased cytoplasmic acidification34. This fitness cost was only observed in anaerobic conditions, where aerobic respiration cannot be used to dissipate excess protons efficiently34. Analogous conditions in the female urogenital tract, potentially augmented by environmental acidity, could create a similar selective pressure during human infection that leads to pump downregulation or loss.

This model predicts that adaptation to these conditions would similarly result in the downregulation of FarAB, the other proton-substrate antiporter efflux pump in N. gonorrhoeae. FarAB is a member of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of efflux pumps and effluxes long-chain fatty acids35,36. In our global dataset, 332/4838 (6.86%) of isolates were predicted to have farA LOF mutations, of which the majority (316/332; 95.2%) were due to indels in a homopolymeric stretch of eight ‘T’ nucleotides near the 5’ end of the gene (Supplementary Fig. 2C). farA LOF mutations were associated with patient sexual behavior (p-value = 5.06 × 10−10; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and site of infection (p-value = 1.78 × 10−12; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and overrepresented in cervical isolates: 33 out of 129 (25.6%) cervical isolates contained a farA LOF mutation compared to 117 out of 2246 urethral isolates (5.21%; OR = 6.25, 95% CI [3.90–9.83], p-value = 3.24 × 10−13; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), 3 out of 106 pharyngeal isolates (2.83%; OR = 11.70, 95% CI [3.50–61.61], p-value = 3.80 × 10−7; two-sided Fisher’s exact test), and 12 out of 246 rectal isolates (4.88%; OR = 6.66, 95% CI [3.19-14.80], p-value = 1.57 × 10−8; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 14 and 15). farA LOF mutations were prevalent also in our Australian validation dataset31 (225/2180; 10.32%) and again associated with sexual behavior (p-value < 2.20 × 10−16; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) and site of infection (p-value < 2.20 × 10−16; two-sided Fisher’s exact test) (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 16 and 17). The phylogenetic distribution of farA LOF indicated sustained transmission (Supplementary Fig. 3) and overlapped with that of mtrA LOF mutations (48.9% of isolates with mtrA LOF mutations also had farA LOF mutations), potentially indicating additive contributions to cervical adaptation. Furthermore, MtrR activates farAB expression by repressing the farR repressor37. This cross-talk between the two efflux pump operons indicates that in mtrCDE overexpression strains where MtrR activity is impaired, the effect of farA LOF—like mtrA LOF—may be masked. We did not observe frequent LOF mutations in the sodium gradient-dependent MATE family efflux pump NorM38 or in the ATP-dependent ABC family pump MacAB39 (Supplementary Table 3). The prevalence and cervical enrichment of farA LOF mutations and the relative rarity of LOF mutations in other non-proton motive force-driven pumps suggest that cytoplasmic acidification may be a mechanism by which the female urogenital tract selects for efflux pump loss.

Meningococcal mtrC LOF is driven by urogenital adaptation

N. meningitidis, a species closely related to N. gonorrhoeae, colonizes the oropharyngeal tract and can cause invasive disease, including meningitis and septicemia40. We characterized mtrC diversity in a collection of 14,798 N. meningitidis genomes, reasoning that the cervical environmental pressures that select for efflux pump LOF in the gonococcus will be rarely encountered by the meningococcus. In agreement with this, the ‘GC’ hexarepeat associated with most gonococcal mtrC LOF mutations was less conserved in N. meningitidis; only 9684/14798 (65.4%) isolates contained an intact hexarepeat compared to 4644/4847 (95.8%) of N. gonorrhoeae isolates (p-value < 2.2 × 10−16; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). In this same collection, we observed mtrC LOF due to deletions in the hexarepeat region in only 82 meningococcal isolates (0.55%), with a similar frequency of 25/4059 (0.62%) in a curated dataset comprising all invasive meningococcal disease isolates collected in the UK from 2009 to 201341. The observed interruption of ‘GC’ dinucleotide repeats, predicted to result in a lower mutation rate42, and the relative rarity of mtrC LOF mutations suggests that efflux pump loss is not generally adaptive in N. meningitidis. However, a urogenitally-adapted meningococcal lineage has recently emerged in the US associated with outbreaks of non-gonococcal urethritis in heterosexual patients43–45. In isolates from this lineage, the prevalence of mtrC LOF mutations was 18/207 (8.70%), substantially higher than typical N. meningitidis and comparable to the prevalence of gonococcal mtrC LOF mutations in MSW in our global dataset (4.47%). We compared the frequency of mtrC LOF mutations in the urogenital lineage to geographically and genetically matched isolates (i.e., all publicly available n = 456 PubMLST ST-11 North American isolates) and observed a significant difference in prevalence (18 out of 207 or 8.70% versus 2 out of 249 or 0.80%; OR = 11.71, 95% CI [2.75–105.37], p-value = 3.31 × 10−5; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Most mtrC LOF mutations occurred due to the same hexarepeat two base pair deletion that we previously observed for N. gonorrhoeae, and in line with this, mtrC LOF in this urogenital lineage arose multiple times independently similarly to gonococcal mtrC LOF mutations (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 3). farA LOF mutations were not observed in this meningococcal lineage. We conclude that MtrCDE efflux pump LOF is rare in typical meningococcal strains that inhabit the oropharynx but elevated in frequency in a unique urogenitally-adapted lineage circulating in heterosexuals, indicative of potential ongoing adaptation to the cervical niche. Our results suggest that efflux pump loss is broadly adaptive for cervical colonization across pathogenic Neisseria.

Fig. 4. mtrC LOF mutations are enriched in a lineage of ST-11 urogenitally-adapted N. meningitidis.

A core-genome maximum likelihood phylogeny based on 25045 SNPs was estimated of all North American ST-11 N. meningitidis strains from PubMLST (n = 456; accessed 2019–09–03) rooted with meningococcal reference genome MC58. Membership in the ST-11 urogenital clade (dark blue) is defined as in Retchless et al.44. Genomes with mtrC LOF mutations are indicated in pink. Branch length represents substitutions per site.

Discussion

In an era in which widespread antimicrobial pressure has led to the emergence of extensively drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae46, isolates that appear to have reverted to susceptibility still arise9,10, demonstrating that antibiotic and host environmental pressures interact to shape the evolution of N. gonorrhoeae. Here, we showed that frameshift-mediated truncations in the mtrC component of the MtrCDE efflux pump are the primary mechanism for epistatic increases in antibiotic susceptibility across a global collection of clinical gonococcal isolates, as suggested by prior work20,22. mtrC LOF mutations are enriched in cervical isolates and a frameshifted form of the pump activator MtrA exhibits similar trends, supporting a model in which reduced or eliminated mtrCDE efflux pump expression contributes to adaptation to the female genital tract. We hypothesized that the mechanism by which this occurs is through increased cytoplasmic acidification in anaerobic conditions34 and demonstrated that LOF mutations in farA, encoding a subunit of the other proton motive force-driven pump FarAB, were likewise enriched in cervical isolates. The LOF mutations we observed in mtrC and farA primarily occurred in short homopolymeric sequences (though with low numbers of repeated units) and thus may occur at higher rates than insertions or deletions in non-repetitive regions or nonsense mutations, similar to other resistance suppressor mutations47, though this will need to be confirmed in future experiments. In total, 42.6% of cervical isolates in the global dataset and 32.6% in the validation dataset contained a LOF mutation in either mtrC, farA, or mtrA, indicating that efflux pump downregulation via multiple genetic mechanisms is prevalent in cervical infection. These results complement prior studies suggesting that mtrR LOF resulting in increased resistance to fecal lipids plays a critical role in gonococcal adaptation to the rectal environment48,49 and taken together suggest a model in which the fitness benefit of efflux pump expression is highly context dependent.

Other selective forces could also have contributed to the observed enrichment of LOF mutations in cervical isolates. For instance, iron levels modulate mtrCDE expression through Fur (the ferric uptake regulator) and MpeR50. Iron limitation results in increased expression of mtrCDE, and conversely, iron enrichment result in decreased expression, suggesting a fitness cost for mtrCDE expression during high iron conditions. Variation in environmental iron levels, such as in the menstrual cycle, may provide another selective pressure for LOF mutations to arise particularly when MtrR function is impaired through active site or promoter mutations. Differing rates of antibiotic use for gonorrhea in men and women due to increased asymptomatic infection in women might also select for mtrC LOF mutations, but this would not explain the associations we observed for the non-antibiotic substrate efflux pump farAB or the increased frequency of mtrC LOF mutations in urogenitally-adapted meningococci. RNA sequencing from men and women infected with gonorrhea demonstrated a 4-fold lower expression of mtrCDE in women, re-affirming the idea that efflux pump expression in the female genital tract incurs a fitness cost51.

Despite significant associations, only a proportion of cervical isolates exhibited these LOF genotypes, suggesting variation in cervix-associated pressures or indicating that cervical culture specimens were obtained before niche pressures could select for pump downregulation. This variation could also lead to mixed populations of efflux pump wild-type and LOF strains; however, because only one clonal isolate per site per patient is typically sequenced in clinical surveillance studies, we would be unable to detect this intra-host patient diversity. Targeted amplicon sequencing of LOF loci directly from patients in future studies would help to assess whether this intra-host diversity plays a role in infection and transmission. In particular, this intra-host pathogen diversity could facilitate transmission from the female genital tract to other sites of infection, where efflux pump activity incurs less of a fitness cost. In those new sites, isolates with wild-type efflux pump loci in the mixed population could selectively expand relative to LOF efflux pump strains and also serve as possible recombination donors of wild-type alleles. This standing genetic variation would, therefore, facilitate gonococcal adaptation across different mucosal niches. Additionally, while the cervix is the primary site of infection and source for culture in women, the selective pressures at play may include other sites more broadly in the female genital tract and may be influenced by the presence of other microbial species both pathogenic and commensal.

Our model extended to the other pathogenic Neisseria species, N. meningitidis, in that a urogenital clade transmitting in primarily heterosexual populations appeared to be undergoing further urogenital adaptation via the same mtrC frameshift mutation that was most commonly observed for N. gonorrhoeae. In the absence of data on cases of cervicitis, we hypothesized that for this meningococcal lineage, efflux pump LOF emerged in the female urogenital tract and was transmitted to heterosexual men resulting in the enrichment we observed. Efflux pumps are common across Gram-negative bacteria52, and their loss may be a general adaptive strategy for species that face similar pressures as N. gonorrhoeae and urogenitally-adapted N. meningitidis. In support of this, clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with truncations in genes homologous to mtrC53,54 and exhibiting antibiotic hypersensitivity have been obtained from cystic fibrosis patients, in whom the thick mucus in airway environments can likewise exhibit increased acidity and decreased oxygen availability55,56.

Our results also suggest potential therapeutic avenues for addressing the emergence of multidrug-resistant gonococcal strains. Selective knockdown of MtrCDE homologs in other bacteria via antisense RNA57 and bacteriophages58 has successfully re-sensitized resistant strains and enhanced antibiotic efficacy, and ectopic expression in N. gonorrhoeae of the mtrR repressor in a cephalosporin-resistant strain enhances gonococcal killing by β-lactam antibiotics in the mouse model59. Our population-wide estimated effect sizes for mtrC LOF mutations provide a prediction for the re-sensitization effect of MtrCDE knockdown across multiple genetic backgrounds and suggest particularly strong effects for the macrolide azithromycin (Supplementary Fig. 4). Because the correlation between MIC differences and clinical efficacy is still not well understood60,61, follow up studies to assess treatment efficacy differences in patients with and without mtrC LOF strains can help to quantify the expected effect of MtrCDE knockdown in the clinical context.

In summary, by analysis of population genomics and patient clinical data, we have shown that pathogenic Neisseria can use multiple avenues of efflux pump perturbation as an adaptive strategy to respond to host environmental pressures and illustrate how these host pressures may result in increased antibiotic susceptibility in N. gonorrhoeae.

Methods

Genomics pipeline

Reads for isolates with either associated azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone MIC metadata were downloaded from datasets listed in Supplementary Table 1. Reads were inspected using FastQC version 0.11.7 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and removed if GC content diverged notably from expected values (~52–54%) or if base quality was systematically poor. We mapped read data to the NCCP11945 reference genome (RefSeq accession: NC_011035.1) using BWA-MEM (version 0.7.17-r1188)62,63 and deduplicated reads using Picard (version 2.8.0) (https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard). BamQC in Qualimap (version 2.2.1)64 was run to identify samples with less than 70% of reads aligned or samples with less than 40X coverage, which were discarded. We used Pilon (version 1.16)65 to call variants with mindepth set to 10 and minmq set to 20 and generated pseudogenomes from Pilon VCFs by including all PASS sites and alternate alleles with AF > 0.9; all other sites were assigned as ‘N’. Samples with greater than 15% of sites across the genome missing were also excluded. We created de novo assemblies using SPAdes (version 3.12.0 run using 8 threads, paired end reads where available, and the --careful flag set)66 and quality filtered contigs to ensure coverage greater than 10X, length greater than 500 base pairs, and total genome size approximately equal to the FA1090 genome size (2.0–2.3 Mbp). We annotated assemblies with Prokka (version 1.13)67, and clustered core genes using Roary (version 3.12)68 (flags -z -e -n -v -s -i 92) and core intergenic regions using piggy (version 1.2)69. A recombination-corrected phylogeny of all isolates was constructed by running Gubbins (version 2.3.4) on the aligned pseudogenomes and visualized in iTOL (version 4.4.2)70–72. All isolates with associated metadata and accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Data 3 and 4.

Resistance allele calling

Known resistance determinants in single-copy genes were called by identifying expected SNPs in the pseudogenomes. For categorizing mosaic alleles of mtr, we ran BLASTn (version 2.6.0)73 on the de novo assemblies using a query sequence from FA1090 (Genbank accession: NC_002946.2) comprising the mtr intergenic promoter region and mtrCDE. BLAST results were aligned using MAFFT (version 7.450)74 and clustered into distinct allelic families using FastBAPS (version 1.0.0)75. We confirmed that horizontally-transferred mtr alleles associated with resistance from prior studies5 corresponded to distinct clusters in FastBAPS. A similar approach was used to cluster penA alleles after running BLASTn with a penA reference sequence from FA1090. Variant calling in the multi-copy 23S rRNA locus was done by mapping to a modified NCCP11945 reference genome containing only one copy of the 23S rRNA and analyzing variant allele frequencies76. We identified truncated MtrR proteins using Prokka annotations, and mutations in the mtr promoter region associated with upregulation of mtrCDE (A deletion and TT insertion in inverted repeat, mtr 120) using an alignment of the mtr promoter from piggy output.

Phenotype processing and linear models

We doubled GISP azithromycin MICs before 2005 to account for the GISP MIC protocol testing change77. Samples with binary resistance phenotypes (i.e., “SUS” and “RES”) were discarded. For samples with MICs listed as above or below a threshold (indicated by greater than or less than symbols), the MIC was set to equal the provided threshold. MICs were log2-transformed for use as continuous outcome variables in linear modeling and GWAS. We modeled transformed MICs using a panel of known resistance markers11,12 and included the recently characterized mosaic mtrCDE alleles5 and rplD G70D substitution78 conferring azithromycin resistance, as well as isolate country of origin. Formulas called by the lm function in R (version 3.5.1) for each drug were (with codon or nucleotide site indicated after each gene or rRNA, respectively):

Azithromycin: Log_AZI ~ Country + MtrR 39 + MtrR 45 + MtrR LOF + mtrR promoter + mtrRCDE BAPS + RplD G70D + 23S rRNA 2059 + 23S rRNA 2611.

Ceftriaxone: Log_CRO ~ Country + MtrR 39 + MtrR 45 + MtrR LOF + mtrR promoter + penA BAPS + PonA 421 + PenA 501 + PenA 542 + PenA 551 + PorB 120 + PorB 121.

Ciprofloxacin: Log_CIP ~ Country + MtrR 39 + MtrR 45 + MtrR LOF + mtrR promoter + GyrA 91 + GyrA 95 + ParC 86 + ParC 87 + ParC 91 + PorB 120 + PorB 121.

To visualize the continuous MICs using thresholds as on Fig. 1, we binarized MICs using the CLSI resistance breakpoint for ciprofloxacin, the CLSI non-susceptibility breakpoint for azithromycin, and the CDC GISP surveillance breakpoint for ceftriaxone.

GWAS and unitig annotation

We used a regression-based GWAS approach to identify novel susceptibility mutations. In particular, we employed a linear mixed model with a random effect to control for the confounding influence of population structure and a fixed effect to control for isolate country of origin. Though the outcome variable (log2-transformed MICs) is the same, in contrast to the linear modeling approach described above, which models the linear, additive effect of multiple, known resistance mutations, regression in a GWAS is usually run independently and univariately on each variant for all identified variants in the genome, providing a systematic way to identify novel contributors to the outcome variable. Linear mixed model GWAS was run using Pyseer (version 1.2.0 with default allele frequency filters) on the 480,902 unitigs generated from GATB (version 1.3.0); the recombination-corrected phylogeny from Gubbins was used to parameterize the Pyseer population structure random effects term and isolate country of origin was included as a fixed effect covariate. To create the Manhattan plot, we mapped all unitigs from the GWAS using BWA-MEM (modified parameters: -B 2 and -O 3) to the pan-susceptible WHO F strain reference genome (Genbank accession: GCA_900087635.2) edited to contain only one locus of the 23S rRNA. Significant unitigs were annotated using Pyseer’s annotation pipeline. Unitigs mapping to multiple sites in the genome and in or near the highly variable pilE (encoding pilus subunit) or piiC (encoding opacity protein family) genes were excluded, as were unitigs less than twenty base pairs in length. Due to redundancy and linkage, variants will be spanned by multiple overlapping unitigs with similar frequencies and p-values. For ease of interpretation, we grouped unitigs within 50 base pairs of each other and represented each cluster by the most significant unitig. Unitigs with allele frequency greater than 50% were also excluded as they represented the majority allele. Unitig clusters were then annotated by gene or adjacent genes for unitigs mapping to intergenic regions and further analyzed for predicted functional effect relative to the WHO F reference genome in Geneious Prime (version 2019.2.1, https://www.geneious.com).

Identifying LOF and upregulation alleles

To identify predicted LOF alleles of efflux pump proteins, we ran BLASTn on the de novo assemblies using a query sequence from FA1090 (reference genome FA19 was used for mtrA). Sequences that were full-length or approximately full-length (+ /−5 nucleotides) beginning with expected start codons were translated using Python (version 3.6.5) and Biopython (version 1.69)79. Peptides shorter than 90% of the expected full-length size of the protein were further analyzed using Geneious Prime (version 2019.2.1, https://www.geneious.com) to identify the nucleotide mutations resulting in predicted LOF by alignment of the nucleotide sequences. We called mtrCDE overexpression status by identifying the presence of any of the known mtrR promoter mutations, MtrR coding sequence mutations, and mosaic mtrCDE alleles.

Experimental validation

N. gonorrhoeae culture was conducted on GCB agar (Difco) plates supplemented with 1% Kellogg’s supplements80 at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted on GCB agar supplemented with 1% IsoVitaleX (Becton Dickinson) using Etests (bioMérieux) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. We selected a clinical isolate (NY019581) from the multidrug-resistant lineage ST-190123 that contained an mtrC LOF mutation mediated by a two base pair hexarepeat deletion and confirmed via Etests that its MIC matched, within one dilution, its reported MIC. Isolate NY0195 contained mosaic penA allele XXXIV conferring cephalosporin reduced susceptibility and the gyrA S91F substitution conferring ciprofloxacin resistance9. We complemented the mtrC LOF mutation in this strain by transforming it via electroporation80 with a 2 kb PCR product containing a Neisserial DNA uptake sequence and an in-frame mtrC allele, obtained by colony PCR from a neighboring isolate (GCGS0759). After obtaining transformants by selecting on an azithromycin 0.05 μg/mL GCB plate supplemented with Kellogg’s supplement, we confirmed successful transformation by Sanger sequencing of the mtrC gene. No spontaneous mutants on azithromycin 0.05 μg/mL plates were observed after conducting control transformations in the absence of GCGS0759 mtrC PCR product. We conducted antimicrobial susceptibility testing in triplicate using Etests, assessing statistical significance between parental and transformant MICs by a two-sample t-test.

Metadata analysis

Patient metadata were collected from the following publications from Supplementary Table 1 that had information on site of infection: Demczuk et al.82, Demczuk et al.83, Ezewudo et al.84, Grad et al.85, Grad et al.9, Kwong et al.86, Lee et al.15, and Mortimer et al.81. Sites of infection were standardized across datasets using a common ontology (i.e., specified as urethra, rectum, pharynx, cervix, or other). Two-sided Fisher’s exact test in R (version 3.5.1) was used to infer whether there was nonrandom association between mtrC LOF presence and either anatomical site of infection or sexual behavior. For sexual behavior analysis, isolates cultured from multiple sites on the same patient were counted as only one data point.

Meningococcal mtrC analysis

mtrC alleles from N. meningitidis assembled genomes were downloaded from PubMLST (n = 14798; accessed 2019–09–03) by setting (species = “Neisseria meningitidis”), filtering by (Sequence bin size > = 2 Mbp), and exporting sequences for Locus “NEIS1634”87. mtrC LOF alleles were identified as described above. We generated a core-genome maximum likelihood phylogeny of all North American ST-11 N. meningitidis strains from PubMLST (n = 456; accessed 2019–09–03) rooted with meningococcal reference genome MC58 (Genbank accession: AE002098.2) using Roary (version 3.12) (flags -z -e -n -v -s -i 92) and annotated it using metadata from Retchless et al.44 (see Supplementary Data 5 for PubMLST IDs). Overrepresentation of mtrC LOF alleles in the US urogenital lineage compared to selected control datasets was assessed using two-sided Fisher’s exact test in R (version 3.5.1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH/NIAID grant 1R01AI132606-01 and the Smith Family Foundation. T.D.M. is additionally supported by the NIH/NIAID F32AI145157, and K.C.M. is additionally supported by the NSF GRFP. D.H.F.R. was supported by award Number T32GM007753 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. D.A.W. is supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (GNT1123854). Portions of this research were conducted on the O2 high-performance computing cluster, supported by the Research Computing Group at Harvard Medical School. This publication made use of the Meningitis Research Foundation Meningococcus Genome Library (http://www.meningitis.org/research/genome) developed by Public Health England, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, and the University of Oxford as a collaboration and funded by the Meningitis Research Foundation. The authors additionally thank Crista Wadsworth, Samantha Palace, and other members of the Grad Lab for helpful comments during development of the project.

Author contributions

K.C.M., T.D.M., A.L.H., N.E.W., and L.S.B. performed and interpreted genomic analyses. K.C.M., D.H.F.R., and Y.W. performed experimental analyses. D.G. and M.U. provided data and conducted genomic analyses on historical isolates. G.T. and D.A.W. provided data and interpreted results for the validation dataset. S.R.H., M.U., D.A.W., and Y.H.G. supervised the project. K.C.M., T.D.M., and Y.H.G. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Data availability

In Supplementary Data 3–4, we have included accession numbers (via publicly hosted database NCBI SRA) for accessing all raw sequence data used for N. gonorrhoeae analyses. Intermediate outputs from the genomics pipeline (e.g., de novo assemblies) may also be available from the authors upon request. In Supplementary Data 5, we have included accession numbers (via publicly hosted database PubMLST: https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) for accessing all sequence data used for N. meningitidis analyses. Source data underlying all figures are available in Supplementary Data 1–2 or at https://github.com/gradlab/mtrC-GWAS.

Code availability

Code to reproduce the analyses and figures is available at https://github.com/gradlab/mtrC-GWAS or from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Hank Seifert and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kevin C. Ma, Tatum D. Mortimer.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-17980-1.

References

- 1.Olesen SW, et al. Azithromycin susceptibility among Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates and seasonal macrolide use. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;219:619–623. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olesen SW, Grad YH. Deciphering the impact of bystander selection for antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;221:1033–1035. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Buso, L. et al. The impact of antimicrobials on gonococcal evolution. Nat. Microbiol. 10.1038/s41564-019-0501-y (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:587–613. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadsworth, C. B., Arnold, B. J., Sater, M. R. A. & Grad, Y. H. Azithromycin resistance through interspecific acquisition of an epistasis-dependent efflux pump component and transcriptional regulator in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.01419-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rouquette-Loughlin, C. E. et al. Mechanistic basis for decreased antimicrobial susceptibility in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae possessing a mosaic-like mtr efflux pump locus. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.02281-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Quillin SJ, Seifert HS. Neisseria gonorrhoeae host adaptation and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:226–240. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wi T, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grad YH, et al. Genomic epidemiology of gonococcal resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones in the United States, 2000-2013. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214:1579–1587. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yahara, K. et al. Genomic surveillance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to investigate the distribution and evolution of antimicrobial-resistance determinants and lineages. Microb. Genom.10.1099/mgen.0.000205 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Eyre DW, et al. WGS to predict antibiotic MICs for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:1937–1947. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demczuk, W. et al. Equations to predict antimicrobial MICs in Neisseria gonorrhoeae using molecular antimicrobial resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10.1128/AAC.02005-19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hicks AL, et al. Evaluation of parameters affecting performance and reliability of machine learning-based antibiotic susceptibility testing from whole genome sequencing data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1007349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earle SG, et al. Identifying lineage effects when controlling for population structure improves power in bacterial association studies. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16041. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees, J. A., Galardini, M., Bentley, S. D., Weiser, J. N. & Corander, J. pyseer: a comprehensive tool for microbial pangenome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics10.1093/bioinformatics/bty539 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jaillard M, et al. A fast and agnostic method for bacterial genome-wide association studies: Bridging the gap between k-mers and genetic events. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortimer, T. D. & Grad, Y. H. Applications of genomics to slow the spread of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 10.1111/nyas.13871 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Veal WL, Nicholas RA, Shafer WM. Overexpression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump due to an mtrR mutation is required for chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:5619–5624. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.20.5619-5624.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golparian D, Shafer WM, Ohnishi M, Unemo M. Importance of multidrug efflux pumps in the antimicrobial resistance property of clinical multidrug-resistant isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3556–3559. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00038-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veal WL, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Microbiology. 1998;144:621–627. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-3-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Buso L, Golparian D, Parkhill J, Unemo M, Harris SR. Genetic variation regulates the activation and specificity of Restriction-Modification systems in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:14685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenstein BI, Sparling PF. Mutations to increased antibiotic sensitivity in naturally-occurring gonococci. Nature. 1978;271:242–244. doi: 10.1038/271242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimuta K, et al. Emergence and evolution of internationally disseminated cephalosporin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae clones from 1995 to 2005 in Japan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15:378. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bichara M, Pinet I, Schumacher S, Fuchs RP. Mechanisms of dinucleotide repeat instability in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2000;154:533–542. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golparian D, et al. Genomic evolution of Neisseria gonorrhoeae since the preantibiotic era (1928–2013): antimicrobial use/misuse selects for resistance and drives evolution. BMC Genomics. 2020;21:116. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handing JW, Ragland SA, Bharathan UV, Criss AK. The MtrCDE efflux pump contributes to survival of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from human neutrophils and their antimicrobial components. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2688. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warner DM, Folster JP, Shafer WM, Jerse AE. Regulation of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux-pump system modulates the in vivo fitness of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:1804–1812. doi: 10.1086/522964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warner DM, Shafer WM, Jerse AE. Clinically relevant mutations that cause derepression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrC-MtrD-MtrE Efflux pump system confer different levels of antimicrobial resistance and in vivo fitness. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70:462–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folster JP, et al. MtrR modulates rpoH expression and levels of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:287–297. doi: 10.1128/JB.01165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, et al. Gonococcal MtrE and its surface-expressed Loop 2 are immunogenic and elicit bactericidal antibodies. J. Infect. 2018;77:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson DA, et al. Bridging of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages across sexual networks in the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis era. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3988. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12053-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouquette C, Harmon JB, Shafer WM. Induction of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires MtrA, an AraC-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:651–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vidyaprakash, E., Abrams, A. J., Shafer, W. M. & Trees, D. L. Whole-genome sequencing of a large panel of contemporary Neisseria gonorrhoeae clinical isolates indicates that a wild-type mtrA gene is common: implications for inducible antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.10.1128/AAC.00262-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Olivares Pacheco, J., Alvarez-Ortega, C., Alcalde Rico, M. & Martinez, J. L. Metabolic compensation of fitness costs is a general outcome for antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants overexpressing efflux pumps. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.00500-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zgurskaya HI. Multicomponent drug efflux complexes: architecture and mechanism of assembly. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:919–932. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee EH, Shafer WM. The farAB-encoded efflux pump mediates resistance of gonococci to long-chained antibacterial fatty acids. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:839–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee EH, Rouquette-Loughlin C, Folster JP, Shafer WM. FarR regulates the farAB-encoded efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae via an MtrR regulatory mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:7145–7152. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7145-7152.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rouquette-Loughlin C, Dunham SA, Kuhn M, Balthazar JT, Shafer WM. The NorM efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis recognizes antimicrobial cationic compounds. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1101–1106. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1101-1106.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rouquette-Loughlin CE, Balthazar JT, Shafer WM. Characterization of the MacA-MacB efflux system in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:856–860. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stephens DS, Greenwood B, Brandtzaeg P. Epidemic meningitis, meningococcaemia, and Neisseria meningitidis. Lancet. 2007;369:2196–2210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill DM, et al. Genomic epidemiology of age-associated meningococcal lineages in national surveillance: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015;15:1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00267-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bichara M, Schumacher S, Fuchs RP. Genetic instability within monotonous runs of CpG sequences in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1995;140:897–907. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazan JA, et al. Notes from the field: Increase in Neisseria meningitidis-associated urethritis among men at two sentinel clinics - Columbus, Ohio, and Oakland County, Michigan, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2016;65:550–552. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6521a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Retchless AC, et al. Expansion of a urethritis-associated Neisseria meningitidis clade in the United States with concurrent acquisition of N. gonorrhoeae alleles. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:176. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tzeng YL, et al. Emergence of a new Neisseria meningitidis clonal complex 11 lineage 11.2 clade as an effective urogenital pathogen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:4237–4242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620971114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whiley DM, Jennison A, Pearson J, Lahra MM. Genetic characterisation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistant to both ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:717–718. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kime, L. et al. Transient silencing of antibiotic resistance by mutation represents a significant potential source of unanticipated therapeutic failure. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.01755-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Morse SA, et al. Gonococcal strains from homosexual men have outer membranes with reduced permeability to hydrophobic molecules. Infect. Immun. 1982;37:432–438. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.432-438.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shafer WM, Balthazar JT, Hagman KE, Morse SA. Missense mutations that alter the DNA-binding domain of the MtrR protein occur frequently in rectal isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae that are resistant to faecal lipids. Microbiology. 1995;141(Pt 4):907–911. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercante AD, et al. MpeR regulates the mtr efflux locus in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and modulates antimicrobial resistance by an iron-responsive mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1491–1501. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06112-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nudel, K. et al. Transcriptome Analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae during natural infection reveals differential expression of antibiotic resistance determinants between men and women. mSphere10.1128/mSphereDirect.00312-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Du D, et al. Multidrug efflux pumps: structure, function and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:523–539. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vettoretti L, et al. Efflux unbalance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1987–1997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01024-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chalhoub H, et al. Mechanisms of intrinsic resistance and acquired susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients to temocillin, a revived antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40208. doi: 10.1038/srep40208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garnett JP, et al. Hyperglycaemia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa acidify cystic fibrosis airway surface liquid by elevating epithelial monocarboxylate transporter 2 dependent lactate-H(+) secretion. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37955. doi: 10.1038/srep37955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worlitzsch D, et al. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:317–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ayhan DH, et al. Sequence-specific targeting of bacterial resistance genes increases antibiotic efficacy. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan BK, et al. Phage selection restores antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26717. doi: 10.1038/srep26717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen, S. et al. Could dampening expression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump be a strategy to preserve currently or resurrect formerly used antibiotics to treat gonorrhea? MBio. 10.1128/mBio.01576-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Cole MJ, et al. Gentamicin, azithromycin and ceftriaxone in the treatment of gonorrhoea: the relationship between antibiotic MIC and clinical outcome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:449–457. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tapsall JW, et al. Failure of azithromycin therapy in gonorrhea and discorrelation with laboratory test parameters. Sex. Transm. Dis. 1998;25:505–508. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199811000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

- 64.Garcia-Alcalde F, et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2678–2679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walker BJ, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Page AJ, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thorpe HA, Bayliss SC, Sheppard SK, Feil EJ. Piggy: a rapid, large-scale pan-genome analysis tool for intergenic regions in bacteria. Gigascience. 2018;7:1–11. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tonkin-Hill G, Lees JA, Bentley SD, Frost SDW, Corander J. Fast hierarchical Bayesian analysis of population structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:5539–5549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson SR, Grad Y, Abrams AJ, Pettus K, Trees DL. Use of whole-genome sequencing data to analyze 23S rRNA-mediated azithromycin resistance. Int J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2017;49:252–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kersh, E. N. et al. Rationale for a Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptible only interpretive breakpoint for azithromycin. Clin. Infect Dis.10.1093/cid/ciz292 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Ma, K. C. et al. Increased power from bacterial genome-wide association conditional on known effects identifies Neisseria gonorrhoeae macrolide resistance mutations in the 50S ribosomal protein L4. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.24.006650v1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Cock PJ, et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1422–1423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dillard, J. P. Genetic Manipulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Curr Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 4, Unit4A 2, 10.1002/9780471729259.mc04a02s23 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Mortimer, T. D. et al. The distribution and spread of susceptible and resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae across demographic groups in a major metropolitan center. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.30.20086413v1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Demczuk W, et al. Whole-Genome Phylogenomic Heterogeneity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates with Decreased Cephalosporin Susceptibility Collected in Canada between 1989 and 2013. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:191–200. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02589-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Demczuk W, et al. Genomic Epidemiology and Molecular Resistance Mechanisms of Azithromycin-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Canada from 1997 to 2014. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:1304–1313. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03195-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ezewudo MN, et al. Population structure of Neisseria gonorrhoeae based on whole genome data and its relationship with antibiotic resistance. PeerJ. 2015;3:e806. doi: 10.7717/peerj.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grad YH, et al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime in the USA: a retrospective observational study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14:220–226. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kwong JC, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals transmission of gonococcal antibiotic resistance among men who have sex with men: an observational study. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94:151–157. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jolley KA, Bray JE. & Maiden, M. C. J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

In Supplementary Data 3–4, we have included accession numbers (via publicly hosted database NCBI SRA) for accessing all raw sequence data used for N. gonorrhoeae analyses. Intermediate outputs from the genomics pipeline (e.g., de novo assemblies) may also be available from the authors upon request. In Supplementary Data 5, we have included accession numbers (via publicly hosted database PubMLST: https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) for accessing all sequence data used for N. meningitidis analyses. Source data underlying all figures are available in Supplementary Data 1–2 or at https://github.com/gradlab/mtrC-GWAS.

Code to reproduce the analyses and figures is available at https://github.com/gradlab/mtrC-GWAS or from the authors upon request.