Abstract

The presence of mycotoxins in food has created concern. Mycotoxin prevalence in our environment has changed in the last few years maybe due to climatic and other environmental changes. Evidence has emerged from in vitro and in vivo models: some mycotoxins have been found to be potentially carcinogenic, embryogenically harmful, teratogenic, and to generate nephrotoxicity. The risk assessment of exposures to mycotoxins at early life stages became mandatory. In this regard, the effects of toxic compounds on zebrafish have been widely studied, and more recently, mycotoxins have been tested with respect to their effects on developmental and teratogenic effects in this model system, which offers several advantages as it is an inexpensive and an accessible vertebrate model to study developmental toxicity. External post-fertilization and quick maturation make it sensitive to environmental effects and facilitate the detection of endpoints such as morphological deformities, time of hatching, and behavioral responses. Therefore, there is a potential for larval zebrafish to provide new insights into the toxicological effects of mycotoxins. We provide an overview of recent mycotoxin toxicological research in zebrafish embryos and larvae, highlighting its usefulness to toxicology and discuss the strengths and limitations of this model system.

Keywords: zebrafish, larvae, embryos, mycotoxins, mixtures, toxicology, model system, embryonic development

1. Introduction

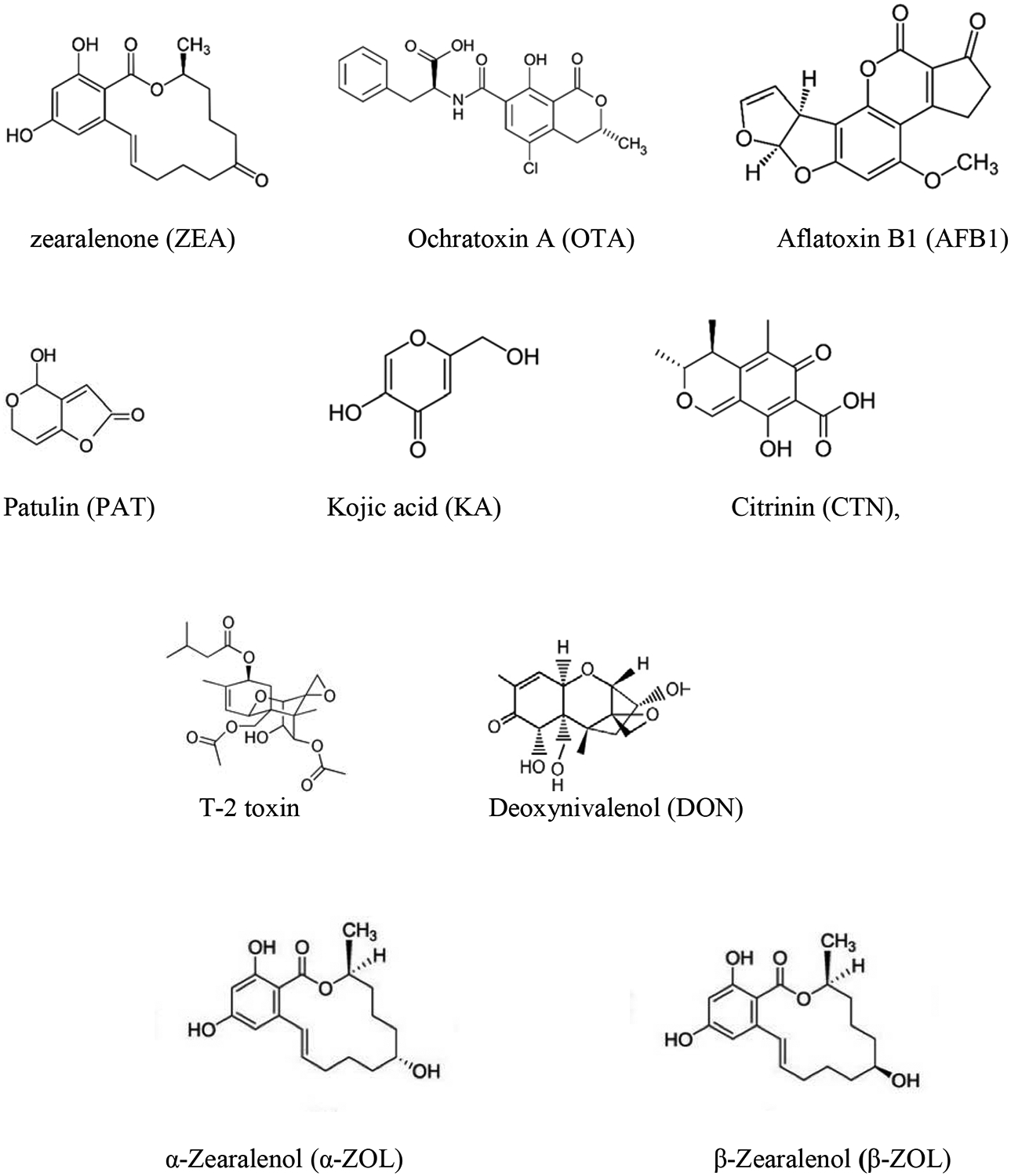

The presence of mycotoxins in the food chain has been reported in several publications (Stanciu et al., 2017; Marijani et al., 2019; Juan et al., 2017, 2019). In fact, it constitutes one of the most important aspects involved in spoilage of food and also in feed (Tirado et al., 2010). Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi (molds), such as Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., and Fusarium spp., in the matrix where they grow (food and feed) and can appear during growing, harvesting, storage and processing. They probably perform ecological functions against other organisms and protect fungi from oxidative stress; however, the main importance of these compounds is the toxicological chronic effects that can cause in humans and animals and acute toxicity which has occurred very occasionally (Zain 2011). There are approximately 400 compounds currently recognized as mycotoxins, although only few of them are addressed by food legislation. The qualitative and quantitative mycotoxin profile which a mold produces on a food commodity depends on the ecological and processing parameters of the particular foodstuff and the fungi spp. (Tirado et al., 2010). Mycotoxins are classified into different groups depending on their molecular structure, producer fungus, and toxicity (Juan-García et al., 2013). Figure 1 collects the chemical structure of some mycotoxins.

Figure 1.-.

Chemical structures of mycotoxins studied in vitro by using zebrafish model

Mycotoxin contamination in food and feed includes coffee, apples, tomato, strawberries, grain cereals, dried fruits and a big etc. where geographic origin, post-harvest processes and storage times play an important role. In general, food contains many naturally occurring chemicals, of different origin and from different source and combined exposure to multiple chemical is also of great interest (Agahi et al.., 2020; Juan-García et al., 2018, 2019a, 2019b, 2020) as there are limitations in knowledge and scientific evidence regarding potential harm in humans, animals and environment as well as the risk assessment of mixtures of chemical exposures (EFSA, 2019). The importance of mycotoxins detection in food, which will be consumed by humans and animals is to understand and determine how mycotoxins will affect cell mechanisms. So that, the development of methods and the use of biological models that hit to study pathways implicated in the toxic effect of mycotoxins is necessary and nowadays becoming crucial for mycotoxins legislation (Juan-García et al., 2013; EFSA, 2019).

World Health Organization (WHO) reports that acute and chronic effects of mycotoxins on humans and animals (especially monogastrics) depends on species and susceptibility of an animal within a species. There are more cases of acute toxicity for animals than for humans although control of mycotoxins for food and feed is mandatory for some of them, as set in legislation and followed by authorities. The most important acute effect reported for mycotoxins have been aflatoxicosis (due to high doses of aflatoxins) and associated in producing damage to the liver (WHO, 2018). Nonetheless, chronic effects as genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, DNA damage, cancer in several organs (liver, kidney, spleen), effects in fetal development and on the immune system, gastrointestinal disturbances, nauseas, abdominal pain, vomiting, skin irritation, intestinal irritation, diarrhea, alterations in bone marrow, etc. have been associated several mycotoxins (Zain 2011).

The effects of these natural food contaminants on human health are known and have been classified by the International Agency for Research in Cancer (IARC) (IARC, 1993) for chronical exposure. Several in vitro studies have suggested the capacity of mycotoxins to alter mitochondrial membrane potential, cell cycle distribution, cell death, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These assays have been performed in different cell lines, e.g., in Caco-2 cells (Ferrer et al., 2008; Prosperini et al., 2013a, 2013b), in HepG2 cells (Juan-García et al., 2019), in CHO-K1 cells (Mallebrera et al., 2015), in murine monocyte macrophage (RAW 264.7) (Dornetshuber et al., 2007), in human non-small cell lung cancer (A549) cells (Gammelsrud et al., 2012). Other mycotoxins have been studied, e.g., enniatins (ENs), beauvericin (BEA), patulin (PAT), zearalenone (ZEA), T-2 toxin, and ochratoxin A (OTA). The main limitations of in vitro models include the lack of interactions with other cells, lack of hormonal or immunological influences, and the levels of gene expression involved in the response to mycotoxin exposure (Ghallab et al., 2014). The translation of in vitro data into meaningful in vivo effects remains unknown. Alternative model systems, e.g., animal models, have been developed and their results are promising (Csenki et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2017). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines propose the zebrafish model (i.e., Danio rerio) as a good model system to study ecotoxicology and neurodevelopmental toxicity (OECD 236, 2013). The properties of this model are consistent with the principle of 3Rs (i.e., Replacement, Reduction, Refinement): there is an increasing demand for alternative model systems for which the number and the suffering of experimental animals can be minimized (Novak et al., 2020). The zebrafish is an omnivorous small specie easy to keep and readily reproducing in the laboratory and has transparent embryos which is suited for high-throughput toxicological studies examining developmental and neuro behavioral toxicity. The transparency of zebrafish embryos allows the application of high-resolution imaging techniques at all stages of development. Zebrafish embryos up to five days post fertilization (dpf) are considered as non-protected life stages by the EU Directive 2010/63/EU also by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in the United States; hence zebrafish embryos represent replacement method for testing adult animals (Strähle et al., 2012; Lawrence et al., 2009).

Zebrafish has also been used to measure estrogen receptor activation in vivo, e.g., Competitive Estrogen Receptor Binding Assay, OECD-TG-455, 457, 493 (OECD, 2012). Zebrafish can be used in toxicology to study hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity due to the property of transparent embryos, which makes it easier to observe the embryogenetic process than in mammal fetus (Hill et al., 2005; Reimers et al., 2006).

The zebrafish model correlates fairly well with the results from other vertebrate model systems (Ablain and Zon, 2013; Forn-Cuní et al., 2017), and from cell lines (Rainieri et al., 2017). Chemical structure of mycotoxins is highly diverse (Juan-García et al., 2013), therefore, specific toxicological effects cannot be estimated on the basis of molecular structure and chemical interactions.

Neuronal differentiation into mature neurons is comparable between humans and zebrafish (Tropepe et al., 2003). Although the neurotransmitter system evolves faster in zebrafish than in humans, it is detected similarly at 48 hpf in zebrafish and at week 13 in humans (Semple et al., 2013 and Jeong et al., 2008). The formation, differentiation, and connectivity of neurons require molecular mechanism that appear to be conserved in all vertebrates. We review some of the current literature on the toxicological effects associated with mycotoxin exposure in the early stages of larval zebrafish.

2. Observational changes in early stages and development in zebrafish

Zebrafish are small and transparent as embryos, high spawning rate, develop relatively rapidly, and induce a fairly low cost to raise. Such characteristics make zebrafish suitable to assess embryonic development (OECD, 2013), especially because embryogenesis is non-placental and external to the mother. Adverse endpoints, e.g., coagulation, missing heartbeat, tail detachment, developmental abnormalities such as yolk sac, pericardial edema, spinal deformity, abnormal pigmentation, fin and tail malformations, hatching, incomplete development of the head and eyes are good candidates to evaluate. Several outcomes or live index can also be considered, e.g., heart beats, blood flow, blood coagulation as well as somatic indices such as body weight, total length, gonadal and hepatic changes.

Evaluating development at different time windows is an endpoint to consider: at 1 dpf nervous system is formed, at 3 dpf the blood brain barrier is observed, after 20–24 hpf the neurotransmitter systems are detected and are almost complete at 5 dpf, and for this last time point, a broad range of behaviors is also noticeable (Jeong et al. 2008, Rico et al. 2011; Horzmann et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2017).

3. Developmental toxicity of mycotoxins in zebrafish

To have developmental effects, a mycotoxin must be present in food commodities (Juan et al., 2017b, 2019; Oueslati et al., 2018; Stanciu et al., 2018), and in a sufficient amount to induce a particular acute defect in an embryo/larvae during a critical development point or to have a chronical exposure during the development (Juan-García et al., 2019a, 2019b; Klaric et al., 2006; Alassane-Kpembi et al., 2015). A non-exhaustive list of studies examining the effects of mycotoxin exposure in early zebrafish developmental stages are summarized in Table 1. To assess the effects of mycotoxin exposure in early stages of zebrafish, substances are dissolved in water at the desired concentration; however, it is sometimes difficult to quantify, and in this case, egg microinjection can be used to measure effects at such level (Wu et al. 2013, 2016; Khezri et al. 2018).

Table 1.

Experimental studies carried out over the last years of mycotoxins in zebrafish during early development stages.

| Mycotoxin | Biological substrate | Dose (time, age) | Assay | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZEA | Zebrafish 10 months old (2 female and 4 male) | 100, 320, 1000 and 3200 ng/L 42 days |

a) Estrogenic potential (rYES) on days 4, 7, 12 and 21. | a)EC50: 500 μg/L ZEA was detected between 57 and 84% and EEQ between 92 and 247% |

Schwartz et al., 2010 |

| b) Mortality, weight, body length and gonad morphology | b) No effect on body length, survival and weight during 21 days exposed to 3200 ng/L. No effect in gonad morphology. None of the testes contained oocytes. The ovaries showed oocytes at the various stages of development without significant differences. | ||||

| c)Reproductive performance | c)Spawning frequency: concentration dependent decrease of 98% Fecundity reduction of 116% Clutch size: negative concentration related response except for 1000 ng/L that reached the same value as control (109%) |

||||

| d)VTG induction | d)Increase after 21 days of exposure between 4.4 and 8.1 fold at the highest concentrations tested (1000ng/L and 3200 ng/L). | ||||

| Zebrafish (juvenile and adults) | 100, 320 and 1000 ng/ L 80–440 eggs 182-day cycle | a) Estrogenic potential (rYES) on days 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 110, and 130. | a) Juvenile: ZEA: between 46 and 86%; EEQ: 91 to 206% rYES < 80ng/L |

Schwartz et al., 2011 | |

| Juvenile assay: Flow rate of 1L/h 140dpf | Reproduction: ZEA: 54 and 96% rYES between 78 and 109 % |

||||

| Adult-reproduction assay: flow of 1920 μL/h 2 female and 4 male | b) Viability, weight and body length | b) Juvenile For all concentrations it ranged from 62 to 80% and specially during the first month. Fish of 140dpf are not affected by ZEA 1000 ng/L revealing that ZEA exhibits a low acute toxicity in many animal species. Increase of body length, weight in females exposed to 1000 ng/L. No effect in males. |

|||

| 84dpf | Reproduction: No mortality recorded, neither in body length, weight. No effect in gonads morphology |

||||

| c)Sex ratio | Juvenile: Higher proportion of female especially after ZEA 320 and 1000 ng/L. Male/female ratio were reduced in 0.37 and 0.41, however no gonadal effect was observed Reproduction: No differences in sex ratio at any concentration assayed |

||||

| d)Depuration: 21 days | d)Increase of spawning frequency and relative fecundity denoting a capacity of recovery of reproductive output. VTG detection: increase in plasma females. In males there was a complete depuration after 21 days. |

||||

| Wild type (WT) zebrafish TL 8 adult female | 0–10 μg/L 21 days | a) Somatic indices: body weight, total length, gonadal and hepatic changes | a) Gonadal change only at high doses (5 and 10 μL). Ovary morphology changes with degenerated follicles |

Muthulakshmi et al., 2018a | |

| b) Apoptosis (Caspase-3, in ovaries) | b) At high doses caspase-3 activity increased significantly. This suggested that ZEA could activate caspase-3 to induce apoptosis. | ||||

| c) RNA extraction and quantitative rt-PCR for genes of hypothalamic- pituitary-gonadal axis | c) Brain genes (ERa and CYP19A1b), liver genes (ERa and VTG) and gonad genes (LHr, StAR, 3P-HSD and CYP19A1b) increased their expression at ZEA 5 and 10 μg/L. | ||||

| d)Histological examination | d) At a higher concentration (10μL) there was irregularity in membrane attachment and oocyte atresia. | ||||

| AB strain zebrafish 50 embryos 4hpf |

350–950 μg/L | a) Development toxicity (24, 48, 72 and 96 hpf) and heart rate measurement (48, 72 and 96 hpf) 10 embryos per group | a) At 24 and 48hpf no deformation was observed below 550 μg/L; while at higher hpf spine curvature was noted. Pericardial edema, hyperemia, yolk sac edema and spine curvature at 750 and 950 μg/L at 72 and 96 hpf. Abnormal swimming behavior in circular movement in the embryos of 750 and 950 μg/L ZEA | Muthulakshmi et al., 2018b | |

| After 48hpf a marginal increase was observed at 950 μg/L, while no effect was observed at 72 hpf. Decrease of heart rate in embryos at 96 hpf for ZEA 950 μg/L | |||||

| b) Biochemical and antioxidant markers (96 hpf): ROS (10 embryos), LPO (20 embryos), NO, GSH (20 embryos), SOD, CAT, GPx, GST (8 embryos), LDH (8 embryos), AP and protein. |

b) -Increase of i) ROS and LPO at 750 and 950 μg/L; ii) NO and LDH at 950 μg/L. -Reduction of SOD, CAT, GPx, GST and GSH at ZEA highest concentrations assayed (750 and 950 μg/L) -AP activity greatly decreased at the 950 μg/L. |

||||

| c) Neurotoxicity (96 hpf): AChE activity (72 hpf), Comet assay, apoptosis and histopathology. | c)-Inhibitory effect on AChE activity at the highest concentrations assayed (750 and 950 μg/L). -Comet assay: DNA damage in zebrafish embryos exposed to 750 and 950 μg/L. -Apoptotic cells at 950 μg/L. -Histology: Embryos shown various changes like morphological alteration, yolk sac edema, swim bladder inflation and abnormal muscle fibers and body curvature in the highest concentration (950 μg/L. |

||||

| Zebrafish: -Embryos 1hpf -Mature male adults | Embryos: 1 ng/L to 5000 μg/L From 24 to 120hpf Adults (n=7): 0.1 to 1000 μg/L 21 dpf |

a) Embryotoxicity tests. Survival and lethal endpoints (coagulation, missing heartbeat, tail detachment and developmental abnormalities) LC10 and LC50 (24 well/plate, 1 embryo/well) | a) 24hpf: for ZEA ≥ 1500 μg/L embryos showed pericardial edema and at 5000 μg/L all embryos stopped development at the tail bud stage after 10h of exposure. 48hpf: for ZEA ≥ 500 μg/L embryos showed dorsal curvature of the body axis and abnormal heart and eye development (estrogenic effects). Yolk sac and pericardial edema from 1000 μg/L. 72hpf: embryos hatched for ZEA ≤1000 μg/L. Edema was detected at 100 μg/L. From 500 μg/L and above pigmentation was reduced, altered eye and heart development and dorsal curvature of the body axis. Degree of curvature was dose dependent (EC50= 596 μg/L 96 to 120 hpf: edema from 50 μg/L, curved body axis from 500 μg/L and reduced pigmentation from 50 μg/L. LC10: from 335 to 1424 μg/L LC50: from 893 to 2854 μg/L |

Bakos et al., 2013 | |

| b) RNA isolation (10 larvae or 1 whole body adult) for rt-PCR: β-actin (control gen) and vitellogenin | b) All ZEA concentrations induce VTG-1 mRNA expression in a time-dependent manner (120hpf). Highest value was measured at 250 μg/L (median effective concentration 3.24 μg/L Low level of VTG was also detected in the negative control. |

||||

| c) ELISA (in adults) (vtg protein levels) | c) All ZEA concentrations induce VTG mRNA | ||||

| Comparison of results revealed that ELISA and rt-PCR methods correlate well as well larval and adult VTG induction rates. | |||||

| Zebrafish estrogen sensitive liver transgenic line Tg(VTG:mCherry) From 3 to 5 dpf |

From 0.1 to 500 μg/L (8 conc.) | a) Testing mCherry inducibility of fluorescent | a) There was a inhomogenicity and a large variation of response | Bakos et al., 2019 | |

| 20 embryos/conc. | b) Dose-response (sensitivity) | b) Concentration dependent fluorescent response. LOEC at 0.1 μg/L Relative strogenicity: 0.78 EC10, EC50 and EC90 were 3.18, 10.75 and 35.17 μg/L, respectively. |

|||

| OTA | Zebrafish embryos of WT, AB strain and Tg(wt1b:GFP) | 0.1–1 μM 96 well/plate: 1 embryo/well |

a) Survival rate (LD50) (96 well/plate) | a) LC50: i) from 6 to 72hpf: 1 μM; ii) from: 24 to 96hpf: 0.97 μM. OTA at different time points lead to a slight difference in embryo’s viability. Dose higher than 0.5 μM OTA exhibited pericardial edema, dark yolk edema and yolk sac edema. |

Wu et al., 2016 |

| 24 well/plate: 10 embryos per well 6hpf |

b) Whole-mount immunostaining for measuring the heart chambers (with MF20 and S46) (24well/plate) 6 to 72 hpf |

b) It was also shown that OTA caused defects in heart chambers at 72hpf: i) 0.25 μM separates and stretches out ventricle and atrium and ii) 1 μM increases the distance between sinus venosus and bulbus arteriosus 1.5-folds. | |||

| c) Renal function: Dextran clearance assay (microinjection) (images at 0 and 7hpf) (96 well/plate, survival embryos after 72hpf OTA treatment) 0.1 to 0.5 μM |

c) Pronephros had shrunk and arranged in a disorganized manner at 0.5 μM OTA reduce the glomerular filtration in embryonic status from 55% to 31% for 0.25 μM OTA and 11 % for 0.5 μM OTA. |

||||

| d) RNA sequencing (RNA- seq) 6 to 48hpf 0.5 μM |

d) OTA inhibited the expression of PRLRa in a dose- dependent manner (0.25 μM OTA to 47% after 24hpf). OTA reduce the phosphorylated levels of STAT5 in a concentration-dependent manner: i) 53% for 0.25 μM and ii) 38% for 0.5 μM. |

||||

| OTA suppressed the phosphorylation of the AKT protein and reduced the levels of serpina1 levels. | |||||

| OTA modulates the PRLRa/STAT5/serpina1 pathway in the embryonic zebrafish. | |||||

| Embryos 0.5 μM OTA-treated for 42hpf caused up-reglation of 7 microRNAs and down-regulation of 5 microRNAs. | |||||

| e) qRT-PCR for microRNA and antagomiR-731 microinjection (performed into the yolk- stream of 1–2 cell stage embryos). 25 embryos per dose 6hpf |

e) -OTA induced miR-731 expression in a dose-dependent manner at 48hpf (higher peaks). -The antogomiR-731 recovered the levels of PRLRa reduced by OTA (from 17 to 26%) and enhanced the PRLRa mRNA levels to 147% in the absence of OTA. PRLRa is a target gene for miR-731 |

||||

| WT AB strain and Tg(LFABP:EGFP) zebrafish embryos | 0.1–0.5 μM 6hpf 20 embryos per dose |

a) Assessment of the viability of embryonic zebrafish (6hpf) | a) The viability decreased when increasing the exposure time and the OTA concentrations to 87% (0.05 μM OTA) and 58% (0.1 μM OTA) 24hpf. OTA > 0.25 μM had pericardial edema and dark yolk sac at 96 hpf. |

Wu et al., 2018 | |

| b) mRNA for genes involved in hemostasis and blood coagulation: fga, fgb, fgg, f2, f7, f7i, f9b, f10, flg and ef. From 6hpf to 48hpf 0.5 μM | b) Genes which participate in coagulation cascade (fga, fgb, fgg, f2, f7, f7i, f9b, f10, flg and proc) where decreased upon OTA treatment. | ||||

| c) rt-PCR for f7, f7i, f9b, cp, vtna and miR-122 From 6 to 72hpf | c) OTA decreased the expression of liver specific genes: f7, f7i, f9b, cp, vtna and the expression of miR-122. OTA toxicity may result in impairment of liver development in embryos. |

||||

| d) Liver fluorescence imaging | d) OTA (0.1 and 0.5 μM) reduced fluorescence in the 96 and 72 hpf embryos. | ||||

| e) Liver tissue observation and histology (96 hpf and 8dpf) | e) 0.25 μM OTA: Caused variously- sized clear vacuoles. 0.5 μM OTA: Cytoplasmatic cavitation, nuclei were located at the margins of hepatocytes and the ratio of nucleus to cytoplasm was increased. |

||||

| f) Whole-mount in situ hybridization | f) OTA (0.25 and 0.5 μM) reduced with the hhex and prox1 expression and it altered hepatocyte proliferation. | ||||

| g) Phospho-histone H3 immunohistostaining | g) The number and the percentage of phosphorylated histone H3 positive cells on liver sections was reduced in the OTA group at 96 hpf. | ||||

| Zebrafish embryos (18 to 24 eggs) (3hpf) | 0.016–5 mg/L 24h 24, 48, 72 and 96hpf |

a) Assessment of development: mortality, development stage, eyes, somites, tail movement and occurrence of oedema (72hpf) | a) OTA induced dose-dependent mortality in embryos. EC50 went from 0.29 to 2.65 mg/L for 96hpf and 24hpf, respectively. LC50 went from 0.36 to 24.22 mg/ L for 24 and after 96hpf. The hatching was happening at 72 and 96hpf and exposures from 0.16 to 0.63 mg/L; however higher OTA doses did not succeed at OTA 1.25 mg/L or higher. |

Tschirren et al., 2018 | |

| Pigmentation and blood flow, heart beats (20–30 sec) at 48 and 72hpf | It was observed a correlation between OTA concentrations and the decrease of the heart rates. After 48 and 72h of exposure from 0.63 mg/L at 72h no heart rates were detected after 2.5 mg/L | ||||

| b) Measurement of ROS (72hpf) | b) OTA increased oxidative stress in treatments higher than 0.078 mg/L. | ||||

| AB strain Zebrafish embryos (one cell stage) | 1, 7 and 10 mg/L Volumes injected into the yolk: 0.22, 0.52, 1.77 and 4.17 nL |

a) Mortality: coagulation, lack of somite formation and lack of heart function | a) Mortality increased along with the injection volume for all three OTA concentrations at 72hpf; no change at 120 hpf. Mortality was i) maximum for 1 mg/L when 4.17 nL were injected, ii) increased progressively at 7mg/L with different volumes and when 4.17nL were injected caused the higher mortality and iii) maximum mortality with low volumes of 10 mg/L. |

Csenki et al., 2019 | |

| 20 embryos/treatment 72 and 120 hpf | OTAα increased mortality with the injected volume. At 120hpf a dose-response relationship was found between the injected volume and embryo mortality. Mortality increased with the injection with the highest volume (38.5%). | ||||

| b) Sublethal: pericardial edema, yolk edema, tail deformation, craniofacial deformation and disintegrated abnormal embryo shape | b) All treatments with all injected volumes increased the frequency and severity of developmental deformities. At 72 hpf: the highest deformity was obtained at 7 mg/L OTA and highest volume injected. At 120 hpf: deformed embryos was the highest in those OTA treated from 0.52 nL and above. |

||||

| 72hpf 1.77 nL 7 mg/L OTA embryos displayed craniofacial deformities, small eyes, curvature of the body axis, yolk deformities, reduced growth rates and edemas. 120hpf: symptoms and deformation got more severe and appear in all body |

|||||

| OTA OTAα |

Zebrafish embryos | OTA: 0.05–2.5μM OTAα: 0.1–2.5 μM |

a) Zebrafish embryo toxicity assay: ZETA (2–5 dpf) | a) OTA at 1 μM developed abnormally embryos by 1dpf which increased at subsequent time-points. All embryos were deformed at OTA concentrations of 1 (2dpf), 0.25 μM (4dpf) and 0.1 μM (5 dpf) | Haq et al., 2016 |

| 24well/plate 5 embryos/well (<2hpf, 4–32 cell stage) |

Teratogenicity was observed at sub-micromolar concentrations (0.05 μM by 5dpf). EC50 for teratogenicity of OTA decreased from 1 to 5 dpf from 0.25 to 0.02 μM, respectively. |

||||

| OTA higher than 0.5 μM was lethal by 2dpf and surviving embryos were severely retarded. | |||||

| OTA 0.05 μM and 4–5 dpf morphological deformities were observed characterized by reduced growth rates, craniofacial deformities, curvature of the body axis and edemas as well as dose-dependent reduction in hatching rates. | |||||

| OTA has acute toxicity but OTα had no significant effect in embryo development as no mortality of embryos were detected after 5dpf. | |||||

| PAT | Zebrafish | PAT: 70μg/L | a)CAT | a) PAT decreased the CAT activity to 7.2 mg protein (100mg/L), respectively. | Ciornea et al., 2019 |

| 7 days | b) GPx | b) PAT decreased GPX activity respect the control (0.17 U/mg) at 100 mg/L with values of 0.11 U/mg. | |||

| c) LPO (MDA measurement). | c) MDA concentration was 0.97 nmol/mg. | ||||

| d) Behavioral parameters (representative locomotion, entries in the upper zone and immobility time) | d) PAT attenuate the swimming all over the tank in a dose-dependent manner; decreased the number of entries in the upper zone and increase the immobility time Locomotor activity: PAT increased this locomotion Such effect reflected an increase of spontaneous alterations percentage for PAT. PAT stimulated the memory formation by slowly improving memory and enhance of anxiety-like behavior. |

||||

| CTN | Wild type AB zebrafish embryos | 20 and 50 μM 24, 72 and 120 hpf |

a) Viability (from 24 hpf to 120 hpf) Whole-mount inmunostaining 10 AB embryos 24 to 72hpf | a) Viability for 50 μM was 71.6% at 72hpf but all dead after 120 hpf; while for 20 μM lethal effect at 72hpf while at 120 hpf viability was 38% | Wu et al., 2013 |

| Heart-specific transgenic line Tg(BMP4:EGFP) | CTN altered the phenotypes of developing heart, including abnormal tube looping, reduced chamber sizes and pericardial edema. | ||||

| Erythrocyte-specific transgenic line Tg(gata1:dsRED)sd2 |

b) Assessment of SV-BA distances in Tg(BMP4:EGFP | b) The SV-BA distance decreased in embryos exposed to CTN 50μM. | |||

| c) Observation histological transverse sections | c) It was also observed the cardiac defects. | ||||

| d) Cardiac functions of zebrafish embryos: *heart rate (48 and 72 hpf) 15 embryos |

d) The heart rate decreased 70% after 50 μM CTN CTN decreased the blood flow rate of embryos. CTN altered the expression of heart-related genes (tbx2a, nkx2.5, bmp4 and jun4). |

||||

| *blood flow rate 15 embryos) Tg(gata1:dsRED)sd2, |

CTN modulated the retinoic acid signaling pathway in control of cardiac patterning 2.3 and 2.4-folds for 24 and 72hpf. miR-139 mimics can reverse heart defects CTN-induced when injected in embryos from 20 to 54% of the effects. |

||||

| AFB1 | WT AB strain Zebrafish embryos 20 embryos 6hpf | 15–150 ng/mL 6 hpf to 7dpf |

a) Viability (from 1 to 7 dpf) and morphology (7dpf). | a) Viability was altered after 150 ng/mL and 7dpf; although for the same dose and 4dpf did not suffer any mortality. No phenotypic defect for any AFB1 treated group. |

Wu et al., 2019 |

| b) Larvae locomotion test (18 larvae/dose, from 6hpf to 7dpf) (average velocity, absolute turn angle and the ratio of moving to nonmoving). 15, 30, 50 and 75 ng/mL (corresponding to half NOEC, NOEC, 2/3 of LC10 and LC10) | b) After 7dpf some of larvae showed patters of unstable shaking, swimming upside down and swimming on a side in a dose-dependent manner. -Average velocity suppressed at low doses (15 ng/mL) but hyperactivity at high doses (30 and 50 ng/mL, 133%); to be suppressed at 75 ng/mL. -Increase in absolute turn angle at 15 ng/mL and decrease at 30 ng/mL. |

||||

| c) mRNA detection (rt- qPCR): gfap (at 24 and 48 hpf), huC (at 24 and 48 hpf), ngfa, atplblb and prtga. 24 and 48 hpf, 75 and 150 mg/mL 25 embryos/dose |

c) gfpa (early neural development) levels were elevated in the 48 hpf embryos treated with 75 and 150 ng/mL. At the highest concentration increases were 1.3- and 1.7- folds for 24 and 48hpf, respectively. huC (trigeminal ganglion and hindbrain neurons): trigeminal ganglion neuro was denser and less clear pattern while hindbrain neurons were both deteriorated at the higher dose assayed (AFB1 150 ng/mL). Its levels were reduced from 66 to 74% for 24 to 48hpf. |

||||

|

ngfa levels were reduced at 24hpf for 75 and 150 ng/mL from 49 to 37%, respectively. atp1b1b: levels were downregulated for 24 and 48hpf at AFB1 150ng/mL prtga levels were elevated at 48hpf 2.2-folds |

|||||

| d) Microarrays analysis (150ng/mL, from 6 to 48 hpf) | d) Nine genes that are known to be involved in neural activity and neurogenesis were differently expressed. | ||||

| e) Inmunostaining (acetylated alfa-tubulin) 40 embryos 24 hpf, 150 ng/mL | e) AFB1 150 ng/mL disturbed development of trigeminal ganglion neurons and in hindbrain areas. | ||||

| OTA T-2 DON ZEA α-ZOL β-ZOL |

Zebrafish AB strain embryos | ZEA: 0.1–7μM α-ZOL and β-ZOL: 1–35 μM OTA: 0.1–1.4μM T-2: 0.1–1μM DON: 0.01–100 mM (injected in embryos of 2hpf) |

a) Developmental toxicity study (48 embryos, from 6 to 96hpf every other 24h) (ID50, EC50 and LC50) Death if tail remains attached to body, embryos with a lack of somite formation or lack of heartbeat | a) Embryonic toxicity: according to ID50, EC50 and LC50 order of toxicity was: T2>OTA>ZEN> α-ZOL>β-ZOL Highest OTA concentration did not interfere in hatching process and no IC50 was calculated. | Khezri et al., 2018 |

| T-2: 0.1–1 μM | b) Locomotor activity (96 embryos/well, 6hpf) Behavioural assays (96, 100 and 120hpf) (dark and light periods) total time active, distance moved, average swimming speed | b) OTA highest concentration, ZEA and α-ZOL and β-ZOL affected behaviour. *OTA exposure: Larval time active and distance moved was not affected; while swimming speed showed a decrease. *ZEA high concentration decrease swimming speed opposite to β-ZOL. *α-ZOL and β-ZOL at high concentrations showed increase of distance moved β-ZOL highest concentration increased the time spent active. |

|||

| In general, β-ZOL affected the swimming parameters in all tested ages and 100hpf was the age that increased the distance moved, time spent active and decrease of mean swimming speed. T2 and DON did not affect larval behaviour or locomotor activity. |

|||||

| AFB1 DON ZEA AFB1 + DON AFB1 + ZEA DON + ZEA AFB1 + DON + ZEA |

WT and Tg(lfabp10a:ds Red; elaA:egfp) (LiPan) zebrafish larvae 48hpf *transgenic was developed to study embryonic development and in vivio screening for hepatotoxins |

Individual: AFB1: 0–1.28 μM DON: 0 −135 μM ZEA: 0 – 18.85 μM Mixtures: AFB1: 0.04 μM DON: 67.5 μM ZEA: 6.28 μM |

a) Viability (LD50) from 48 to 120 hpf 96 well/plate, 1 embryo/wwell | a) Individual: AFB1 was the most toxic mycotoxin. AFB1 and ZEA increased toxicity as the exposure time progressed. AFB1 induced mortality on 72hpf 1.28 and at 96hpf ≥0.64 μM. ZEA induced mortality from 48 to 120 hpf at 9.43 μM and increase along the exposure period. NOAEL at 120hpf: AFB1 0.16 μM; ZEA 6.28 μM. Mixtures: AFB1 + DON at 96 and 120hpf reduced embryo viability. AFB1 + ZEA at 96hpf reduced embryo viability and at 120 hpf killed all embryos. DON + ZEA: no mortality observed AFB1 + DON + ZEA: slightly decreased the viability during 96hpf and decreased even more at 120hpf. |

Zhou et al., 2017 |

| b) High content screening for multi-parametric cytotoxicity assessment. | b) Individual: Liver size: decrease at ZEA 12.6 μM (73.5%). AFB1 and DON did not produce any significant change in liver area. RFP intensity: i) decreased dose-dependently at 0.04 μM AFB1 (66%): ii) decreased at 33.75 and 67.5 μM DON and iii) ZEA at 6.28 and 12.57 μM 31 and 41% respectively. Mixtures: Decreases in liver areas for AFB1 + DON, AFB1 + ZEA and AFB1 + DON + ZEA from 63 to 54%. DON + ZEA increased liver area by 51% RFP intensity: decreased for AFB1 + DON, AFB1 + ZEA and AFB1 + DON + ZEA from 62 to 56%. |

||||

| c) Imaging-morphology (Analysis by HCS) |

c) Individual treatment revealed moderate edema around the area of yolk sac and slightly upward bending for all mycotoxins. Mixtures: AFB1 + DON and AFB1 + ZEA strong bending of body trunk, yolk sac edema and reduced pigmentation. Pericardial edema for AFB1 + ZEA. AFB1 + DON + ZEA slight bending of body trunk, yolk sac edema and reduced pigmentation. DON + ZEA: slight yolk sac edema and bending of tail tip. |

AChE: Acetylcholinesterase.

AFB1: Aflatoxin B1

AP: Acid phosphatase

CAT: Catalase

CIT: Citrinin

DON: Deoxynivalenol

EC50: concentration that caused any deformity in 50% of larvae

EEQ: estrogen equivalent

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Fga: Fibrinogen alpha chain

Fgb: Fibrinogen beta chain

Fgg: Fibrinogen gamma chain

Flg: Plasminogen

GLU: Glucose

GPx: Glutathione peroxidase

GSH: Reduced glutathione

GST: Glutathione S-transferase enzyme

HCS: High content screening

ID50: concentration interfering with hatching in 50% of larvae

LC50: concentration that causes lethality in 50% of larvae

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase

LHr: Luteinizing hormone receptor

LOEC: Lowest effective concentration

LPO: Lipid peroxidation

MTT assay: 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay

NO: Nitric oxide

OTA: Ochratoxin A

PAT: Patulin

PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction

Proc: Protein C

qRT-PCR: Quantitative real time PCR

ROS: Reactive oxygen species

rt-PCR: Real time PCR.

rYES: Recombinant yeast estrogenic screen

StAR: Steirodogenic acute regulatory protein

T-2: Trichothecene mycotoxin

TBARS: Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

Tg(LFABP:EGFP): fluorescent hepatocytes

VTG-1: Vitellogenin 1 gene

ZEA: Zearalenone

ZETA: Zebrafish embryo toxicity assay

α-ZOL: Alpha-zearelenol

β-ZOL: Beta-zearenol

3β-HSD: 3β-hydrosteroid dehydrogenase-1

Mycotoxins are dissolved in water in the early stages of the zebrafish, thus, the main pathway of absorption occurs by inhalation, by gills (early evolved), or during early stages through the chorion (Martins et al. 2018; Felix et al. 2016; Sanden et al., 2012). Despite this, the concentrations used in zebrafish might not be higher than the stablished by OECD 236 for testing compounds (OECD, 2013).

Microinjection technique, mentioned above, enables to administrate the exact amount of the substance in the yolk sac but without overpassing 10% lethality as maximum according to the OCDE guideline for fish embryo test (OECD 236, 2013). Moreover, it is important to consider the period of exposure after embryo microinjection, since enlarging such period may compromise the assay and fall under animal testing regulations as mycotoxin might remain unabsorbed after about 7dpf (165 ± 12 hpf), which corresponds to the time that zebrafish embryos consume their yolk sac completely (Litvak et al., 2003). With microinjection, it is easy to determine the potential capacity of a strain to degrade the toxin and also to select the safest environmental spp. Studies have assayed the embryotoxicity effect of deoxynivalenol (DON) (Khezri et al., 2018) and the biodetoxification of ochratoxin A (OTA) (Csenki et al., 2019). By using microinjection in embryos, it is easy to study the effect of organic substances, which helps to eliminate the hypoxia conditions. It is a useful technique to investigate the toxin detoxification-properties of microbial strains.

Literature reveals that some mycotoxin exposure is associated with brain disorders as autism, suggesting that mycotoxins are potential stressors of the central nervous system either directly or through the gut-brain axis; a complex bidirectional cross-talk between the enteric and central nervous system that acts through neuroendocrine and neuroimmune signals (Muthulakshmi et al., 2018; Juan-García et al., 2019a). The presence of elevated mycotoxins (i.e., deoxynivalenol, de-epoxydeoxynivalenol, aflatoxin M1, ochratoxin A and fumonisin B1) has been reported in body fluids of autistic children (e.g., urine and serum); however, the involved biological mechanisms are unknown (Carter et al., 2019; De Santis et al., 2017a; De Santis et al., 2017b). Several in vitro assays have highlighted the influence of mycotoxins in the modulation of neurodevelopmental processes (Fatemi et al. 2005, 2008; Cordeiro et al. 2015), which may result in neurotoxic damage in the immature brain and in long-term behavioral effects (de Santis et al., 2019). Genes implicated in autism are associated with mycotoxins as demonstrated in the pathogen interactomes which possess or secrete toxins whose effects on genes are catalogued at the Comparative Toxicogenomics database (Davis et al., 2015).

As reported in the literature, the most common mycotoxins present in food (e.g., zearalenone (ZEA), ochratoxin A (OTA), aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), patulin (PAT), kojic acid (KA), citrinin (CTN), T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON), ustiloxin A and ZEA metabolites α-ZOL and β-ZOL), have been studied using the larval zebrafish model (Figure 1 and Table 1).

3.1. Zearalenone and its metabolites

The most studied mycotoxin in zebrafish is zearalenone (ZEA), which is one of the worldwide most common mycotoxin that shows estrogenic activity in the range of natural steroid estrogens present in food. As reported in the literature, it can induce the yolk precursor protein vitellogenin (VTG), affect gonad development, induce atresia of oocytes and inhibition of spermatogenesis, as well as have an impact on egg production and viability, fertilization success, and sexual differentiation (Arukwe et al., 1999; Celius et al., 2000; Keles et al., 2002).

ZEA has been studied in zebrafish either in adult stages (juvenile - short-term, reproduction stages - life-long, old stages - long-term), and in early development stages (embryos and larvae). The estrogenic activity in juvenile (short-term, 42 days) and in reproduction stages (life-long exposure, 182 days) of zebrafish has been studied in vitro by recombinant yeast estrogen screen (rYES), physiology, morphology, and reproduction activity (i.e., spawning frequency, fecundity, fertility and hatch) (Schwartz et al., 2010) (Table 1).

To assess the relative estrogenic activity in vitro, it is common to use rYES with the endpoint being activation of ER-regulated genes and compared it to the natural steroid estrogens such as 17β-estradiol (Routledge et al., 1996). ZEA short-term exposure (42 days) for rYES demonstrated a sigmoid concentration response curve reaching an effective concentration (EC) EC50 ZEA of 500 μg/L, a reduction in spawning frequency (<40%), as well as in relative fecundity (between 74% to 17%); although in life-long ZEA exposure (182 days) no EC50 values of rYES curves were reached or below the detection limits (Schwartz et al., 2010). It was also noticed that relative fecundity was recovered during a ZEA depuration limit of 21 days (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Estrogenic potency of ZEA can also be measured by qRT-PCR through VTG protein levels in larvae and adults by relative abundance of vitellogenin-1 mRNa (vtg-1). Detection of VTG revealed increases between 4.4- and 8.1-folds in short-term exposure (42 days) in zebrafish exposed to high ZEA concentrations (1000–3200 ng/L); while 1.5-folds in life-long exposure (182 days) (ZEA 1000 ng/L) (Schwartz et al., 2010). Bakos et al. (2013) were able to detect VTG values for larvae and adults at exposures of ZEA as low as 0.1 μg/L; however, female adult wild type (WT) zebrafish exposed to ZEA from 0.5 to 10 μg/L for 21 days did not increase the VTG expression, except at the highest ZEA concentrations assayed (Table 1) (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018a).

Due to the strong relation of VTG protein for detecting estrogenicity effects at low levels in some strains, Bakos et al. (2019) developed a transgenic zebrafish line (Tg(vtg1:mCherry)) natural vitellogenin-1 promoter sequence. Embryos 5 dpf of this zebrafish line were tested through a protocol based on the VTG and an estrogenic effect was detectable after seven generations and ZEA 100 ng/L, revealing the suitability of this model for detecting such effect and also the strong estrogenic capacity of ZEA (Schwartz et al., 2010; Bakos et al., 2013 and 2019).

ZEA has been studied in fish embryo toxicity (FET) in AB strain zebrafish embryos by Muthulakshmi et al. (2018b) (4hpf during 96 hpf) and by Bakos et al. (2013) (from 5 dpf to 21 dpf). ZEA LC50 value was 950 μg/L and the induction of developmental defects was observed at doses above 550 μg/L (Table 1 and Muthulakshmi et al., 2018b). A slightly low LC50 value (893 μg/L) was obtained in embryos/larvae exposed for longer time to ZEA at different concentrations (see Table 1) (Bakos et al., 2013). In this last study, developmental effects in heart and eyes were observed as well as morphological alterations (from 500 μg/L and above) revealing that ZEA might interfere in some ontogenic pathways. Effects related to fertility, hatch, embryo survival and gonad morphology for embryo zebrafish (42 and 182 days) exposed to ZEA at different concentrations (100 to 3200 ng/L) have not been detected in zebrafish (Schwartz et al., 2010). When studying growth indices (i.e., condition factor and hepatosomatic index) in female adult wild type (WT) zebrafish exposed to ZEA (from 0.5 to 10 μg/L for 21 days), there was no relevant change; although reduction in gonadosomatic index and increase of caspase 3 activity were obtained. Such effects were only detectable at high ZEA concentrations, highlighting that ZEA can adversely affect the gonad functions in female zebrafish by changing growth indices, histology of the ovary, and apoptosis (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018a).

Toxicity of ZEA has been paired with oxidative stress by inducing developmental alterations, genotoxicity, and neurotoxicity (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018b), which was reported by evaluating oxidative stress and reduction of antioxidant defense by LPO, ROS, NO and GSH, GPx, GST, SOD, CAT, LDH in AB strain zebrafish embryos 4hpf ZEA treated during 96hpf (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018b). The highest values of these enzymes and molecules were reached at the highest ZEA concentration assayed (see Table 1). In a step forward of the toxicity in zebrafish embryos, neurotoxic effects through acetyl cholinesterase (AChE) activity revealed an inhibition of this enzyme, also at the highest ZEA concentrations assayed (750 and 950 μg/L). DNA damage for genotoxicity, apoptosis, and histological changes were also detectable at high doses (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018b).

In an approach to study the implications of ZEA in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, RNA extraction and qRT-PCR for genes related to this axis were explored: brain genes (ERα and CYP19A1b), liver genes (ERα and VTG), and gonad genes (LHr, StAR, 3β-HSD and CYP19a1b). Zebrafish treated with ZEA showed an upregulation of these genes (see Table 1), as well as histopathological effects on ovaries at the highest ZEA concentration assayed (oocyte atresia and oocyte membrane detachment) (Muthulakshmi et al. 2018a), concluding that ZEA seems to impact the reproductive system of zebrafish through the HPG axis.

In summary, studying ZEA mycotoxin in zebrafish larvae stages reveals noticeable effects when concentrations tested were high (>700 μg/L); specifically, for development alterations, FET, enzymes detection, gene expression and neurotoxicity. When studying the main effect associated to ZEA as a potent estrogenic by rYES and VTG measurement, effects were detected at very low concentrations (~0.5 μg/L) which, if converted to human values, are easily reachable in food consumed in normal daily basis.

3.2. Ochratoxin A

OTA is produced by some species of Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp and is among the most abundant food and feed contaminants (Juan et al., 201, 2016). OTA is nephrotoxic, hepatotoxic, and carcinogenic, and increases intestinal permeability which produces macromolecule trafficking through intestinal wall, which in turn strongly impaires the immune system and alters the so-called ‘gut-brain’ axis. It has been classified as Group 1 by IARC.

The presence of OTA has been widely documented in contaminated foodstuff, in blood samples of healthy people and of patients with chronic nephropathy, in serum samples of pregnant women, and in umbilical cord blood serum, which indicates the capability of OTA in passing the placenta barrier (Biasucci et al., 2011; Hallen et al., 1998; Minervini et al., 2013). The exposure to such compound at detectable levels highlights the potential effect in several organs at early development stages. In this sense, zebrafish exposed to OTA at embryo/larvae stages have been studied for morphological and functional effects, as well as for up/down-regulation of developmental genes.

OTA down-regulates gene of prolactin receptor (PRLR) in rats (Marin-Kuan et al., 2006). This gene is implicated in STAT pathway to promote cell growth and differentiation during zebrafish embryogenesis (Hou et al., 2002). Wu et al (2016) verified the effect of OTA in zebrafish embryos measuring the expression of prolactin receptor (PRLRa), a gene involved in organogenesis and osmoregulation. Genes of cell growth and differentiation during development as well as the signal for the physiological control of water and electrolyte balance were evaluated. An alteration of these genes interferes with the development and function of kidneys and skin (Wu et al 2016). All these factors contributed to the disruption of liver development mediated by OTA (Wu et al., 2018) in the following sequencing: OTA activates miR-731 expression, suppresses PRLRa, and subsequently attenuates p-STAT5 and p-AKT signaling, which implies the final adverse effects on renal development and as endpoint the proliferation and differentiation of embryos.

Hepatotoxic effects of OTA have been assayed through transcriptomics on zebrafish embryos of strains WT AB and OTA treated (Wu et al., 2018). It was revealed that genes implicated in homeostasis and blood coagulation are downregulated as well as liver markers (f7, f9b, cp and vtna and the liver-specific micro RNA-122 hepatotoxicity marker), which may result in in the alteration of embryo liver size and/or impairment of its development. On the other hand, the suppression of the expression of two factors was detected, hhex and prox1, which are important transcriptional factors during hepatoblast specification. Wu et al. concluded that the interference of expression of hhex and prox1 by OTA, and subsequently in the hepatocyte proliferation, results in small size of the liver and low levels of coagulation factors and miR-122 (Wu et al 2018). This fact was relevant because genes and pathways in hepatogenesis and liver cancer in zebrafish and humans are quite maintained, which manifests the attention that should be paid in the health risk associated with population, especially in sensible groups as pregnant woman and young children.

One of the most recent studies carried out in zebrafish has been the biodetoxification of OTA through microinjection of different volumes and concentrations (Table 1 and Csenki et al., 2019) in precision. OTA toxicity effects and detoxification vary according the volume injected in the yolk (from 0.22 to 4.17 nL) and OTA doses (1, 7 and 10 mg/L), and effects can be detected even after three days of exposure (Csenki et al., 2019). Mortality results were diverse although the highest mortality was observed when any volume of OTA 10 mg/L was injected. On the other hand, when observing morphological effects, all treatment at all injected volumes increased the frequency and severity of developmental deformities (Csenki et al., 2019).

FET assay for OTA has been tested at several concentrations and damage in embryos increases with the concentration of OTA (Tschirren et al., 2018). Although doses assayed by Tschirren et al. (2918) do not reflect a real scenario of the concentrations present in environment, it raises concern about the effects of OTA. Impairment was showed for OTA EC50 of 0.29 and 2.65mg/L for 96- and 24-hpf, respectively; for heart rate 1.26 mg/L and for oxidative stress 0.067 mg/L, both after 72 hpf. LC50 was 0.36 and 24.22 mg/L for 24 and 96hpf, respectively (Tschirren et al., 2018).

Teratogenicity of OTA and its hydrolyzed compound OTAα with zebrafish embryotoxicity assay (ZETA) was carried out by measuring different scorable endpoints (e.g., morphological deformities, hatching, behavioral responses) on zebrafish embryos. ZETA revealed that such effect was concentration- and time-dependent even at nanomolar concentrations for OTA (Haq et al., 2016). However, for OTAα, such effect was not detectable at any concentration tested, which highlights the importance in decreasing the toxicity of OTA when it is metabolized to a hydrolyzed form (Haq et al., 2016).

In summary, the majority of the studies carried out with OTA in zebrafish larvae stages deal with the expression of genes related to renal development, proliferation of embryos, homeostasis and blood coagulation, revealing a down-regulation for most of the genes studied. Among that, deformities in development and mortality by microinjections in the sac yolk to analyze biodetoxification were reported, indicating that metabolization decreases OTA’s toxicity. Embriotoxicity assays (FET or ZETA) showed higher LC50 values for OTA (0.26 mg/L and 24.22 mg/L, at different larvae zebrafish stages, Table 1) than those obtained with ZEA mycotoxin (Table 1).

3.3. Patulin

Patulin (PAT) is a mycotoxin mostly found in ripe apples and in its derivate products: fruit juices, concentrated fruit juices, reconstituted and fruit nectars, cider, apple compote and apple puree. It has also been found in other fruits although at much lower concentrations as in pears, grapes, and oranges. Commission regulation has legislated PAT at levels between 25 and 50 μg/kg, whereas for baby food products it has been set in 10 μg/kg (Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006). PAT has toxic effects due to its electrophilic reactivity which forms covalent adducts and degrading rapidly detoxification molecules as glutathione either in vivo or in vitro. It also has the capacity of forming complexes with cysteine, lysine, and histidine.

To date, there is only one study where PAT has been studied in zebrafish during 7dpf. PAT effects studied in zebrafish embryos had been antioxidant enzyme activity of CAT, GPx, and lipid peroxidation (LPO through MDA) (Table 1) (Ciornea et al., 2019). CAT and GPx activity decreased in zebrafish embryos treated with PAT, whereas LPO levels increased in a concentration-dependent manner, which indicates that there is an accumulation of ROS in concentrations that cannot be dissolved by common protective cellular mechanisms and that there is an intent of zebrafish to increase the production of antioxidant enzymes to alleviate the excess of ROS generated. Effects of PAT at neurological level have not been reported yet but some behavioral endpoints (e.g., representative locomotion, entries in the upper zone and immobility time) manifest that PAT slows the improvement of memory and enhances anxiety-like behavior (Ciornea et al., 2019).

Although the effect of PAT in zebrafish are scarce, alteration in antioxidant response as well as in the behavioral endpoint is reported in the literature. Increase in the production of antioxidant enzymes and decrease in memory and enhancement anxiety-like behavior as neurological parameters were the consequences reported in larvae zebrafish.

3.4. Citrinin

CTN is a mycotoxin known as organotoxic to kidneys, liver, and digestive apparatus. (Kumar et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2007a). The implications of CTN at developmental toxicity have been known for more than 25 years and include teratogenicity and embryotoxicity in some animal spp. (e.g., rodents and dogs) with fatal final endpoints of renal malformations (Reddy et al., 1982; (Singh et al., 2007b). Literature has also reported that CTN can influence developing hearts and cardiotoxicity (Stainier and Fishman, 1994; Singh et al., 2007b). In this last direction, the effect on zebrafish was studied by Wu et al. (2013) to elucidate the mechanism of CTN cardiotoxicity in developing embryos. Embryos treated with CTN suggested alteration in the heart morphology with malformation, pericardial edema, blood accumulation, incorrect heart looping, and reduced size of the heart chambers. Heart rate and blood flow were decreased through the dysregulation of miR-138, retinoic acid signaling, and tbx2a (Wu et al 2013).

In summary, CTN exerts cardiotoxicity effects in zebrafish larvae stages have been manifested as evidenced by alteration of different heart parameters (pericardial edema, heart looping, rate,…) and in gene expression.

3.5. Aflatoxin B1

AFB1 belongs to the family of aflatoxins and is one of the mycotoxins highly present in fish feed worldwide. Its detection in aquafeed as well as the presence of its fungus producer, Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus, has been reported in samples from South America to Asia. Moreover, toxicological assays of potentiality for studying synergistic, addition or antagonism effects have suggested AFB1 as one of the most studied aflatoxin. Several multi-mycotoxin studies in food and feed have indicated the presence of AFB1 around 70% of the samples (Barbosa et al., 2013, Gonçalves et al., 2018). It usually appears jointly with deoxynivalenol (DON) and ZEA. On the other side, little is known from their toxicity when combined.

Few studies in zebrafish have associated AFB1 with morphological deformities and/or system alterations, e.g., loss of equilibrium, growth retardation, inmunosupression, mortality, unusual swimming patterns (Wu et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2017; Pietsch et al., 2013). The most recent study of AFB1 in zebrafish has been carried out by Wu et al. (2019), who focused on behavior and neurodevelopment in early embryonic stage.

Viability in WT AB strain zebrafish embryos was altered after AFB1 150 ng/ mL in 7 dpf; however, for the same dose, no mortality was detected at 4 dpf (Wu et al., 2019). Swimming pattern of 7 dpf zebrafish was altered in embryos that were treated from 6 hpf with AFB1 from 15 to 75 ng/mL (Wu et al., 2019). The mobility of zebrafish was activated and slowed down at 30–75 ng/mL and 15 ng/mL, respectively.

Neurodevelopment study was carried out in 24 hpf embryos of a transgenic zebrafish Tg (HuC:eGFP) with AFB1. It was observed aberrant morphology of trigeminal ganglion and hindbrain neurons, alterations in levels of neurotoxic markers (gfap and huC), and in genes related to neuroactivity and neurogenesis (down-regulation of ngfa and atp1b1b and upregulation of prtga) (Wu et al., 2019). In consequence, it was suggested that disruption of neural formation and synapse dysfunction may be responsible for the behavioral alteration (Wu et al., 2019).

Zhou et al. (2017) studied the mortality and liver morphological effects of combined mycotoxins ZEA, DON and AFB1 in zebrafish and compared the effect of fish cells (BF-2 cells) and larvae zebrafish (WT and transgenic). Order of mortality when mycotoxins were assayed individually in BF-2 cells was, AFB1>DON>ZEA; and when assayed in zebrafish, AFB1 > ZEA > DON (Zhou et al., 2017). Morphological effects on liver were observed in the same order as for zebrafish. In binary combinations, synergistic effects were observed for AFB1 + DON and AFB1 +ZEA and antagonistic for DON + ZEA; while in tertiary combination, a synergistic effect at very low concentrations to end up with antagonism effect (Zhou et al., 2017).

Alterations reported for AFB1 in zebrafish larvae stages were related to morphology, neurodevelopment behave, swimming and neuroactivity at different ages. One of the most relevant effects reported was its synergism in liver morphology alteration when combined with DON and ZEA.

3.6. Multi-mycotoxins

The use of high-throughput screening methods for studying several mycotoxins in zebrafish might be good, although it has not been carried out yet. Zebrafish is a suitable animal model for screening mycotoxins, as mentioned in the introduction section of this review, due to its characteristics. A high-throughput chemical screen with zebrafish has been design to quantify the dynamics of food intake in live animals (Jordi et al., 2018; Sanden et al., 2012). This initial screening phase allowed to capture the complexity of whole organisms and makes understandable bioactivity and toxicity (Jordi et al., 2018), such as developmental and neurobehavioral toxicity (Krezi et al., 2018).

Screening of five mycotoxins (Ochratoxin A (OTA), T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON), and zearalenone (ZEA) and its metabolites alpha-zearalenol (α-ZEA) and betazearalenol (β-ZEA)) in adult AB strain zebrafish was carried out by Krezi et al., (2018). LC50, EC50, and IC50 parameters were calculated and the order of toxicity was T2 > OTA > ZEA > α-ZEA > β-ZEA. (Krezi et al., 2018). Regarding developmental analysis, OTA was the only mycotoxin that did not interfere in the hatching process (until 96 hpf). Behavioral effects were only observed following exposure to OTA and ZEA and its metabolites α-ZEA and β-ZEA when exposed to a series of non-lethal doses, which demonstrated that mycotoxins are teratogenic and can influence behavior in a vertebrate model.

4. Conclusion

This review highlights the toxic effects of mycotoxin in the early developmental stages of zebrafish and highlights the effects that can be reflected in humans due to similarities of zebrafish with humans. These studies suppose an addition in the puzzle in the complex and yet incomplete mechanism of action of mycotoxins and its effects in neuronal system level. It is revealed that through the studies summarized here, there is a need in mycotoxin research to clarify potential toxic effects at neurological, teratogenic, and or degenerative levels and to increase the knowledge of the role of mycotoxins in development and function of zebrafish. Although some biological interactions of all organs and systems remain to be addressed with zebrafish, it offers wide options for the use of a complex organism instead of in vitro techniques and replaces the use of animal models, implementing the 3Rs, as well as facilitating the assessment of mycotoxins, its translation to humans, and reducing the risks associated in clinical practice.

Highlights:

Zebrafish and its developing forms is a good 3Rs tool for studying mycotoxins’ effects.

Zebrafish is a vertebrate model for studying developmental and teratogenic mycotoxins effects.

Mycotoxins effects at neuronal, teratogenic, and degenerative level are studied in zebrafish.

Zearalenone and Ochratoxin A were the most commonly investigated mycotoxins in zebrafish.

Acknowledgements and source of Funding

This work has been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness AGL2016-77610-R. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow Program within the FAS Division of Science of Harvard University, and by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP5OD021412. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AJG acknowledges Engert’s Lab at MCB Department and Harvard University for the welcome; and University of Valencia and RCC-Harvard University for the award received.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest None

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

5. References

- Agahi F, Font G, Juan C, Juan-García A 2020. Individual and combined effect of zearalenone derivates and beauvericin mycotoxins on SH-SY5Y cells. Toxins, 12, 212; doi: 10.3390/toxins12040212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alassane-Kpembi I, Puel O, Oswald IP (2015) Toxicological interactions between the mycotoxins deoxynivalenol, nivalenol and their acetylated derivatives in intestinal epithelial cells. Arch Toxicol 89:1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos K, Kovács R, Staszny Á, Sipos D, Urbányi B, & Müller F et al. (2013). Developmental toxicity and estrogenic potency of zearalenone in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic Toxicology, 136–137, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos K, Kovacs R, Balogh E, Sipos D, Reining M, & Gyomorei-Neuberger O et al. (2019). Estrogen sensitive liver transgenic zebrafish (Danio rerio) line (Tg(vtg1:mCherry)) suitable for the direct detection of estrogenicity in environmental samples. Aquatic Toxicology, 208, 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa BTS, Pereyra CM, Soleiro CA, Dias EO, Oliveira AA, Keller KA, Silva PPO, Cavaglieri LR, Rosa CAR, 2013. Mycobiota and mycotoxins present in finished fish feeds from farms in the Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Int. Aquat. Res 5, 2e9. [Google Scholar]

- Biasucci G, Calabrese G, Di Giuseppe R, Carrara G, Colombo F, Mandelli B, Maj M, Bertuzzi T, Pietri A and Rossi F, The presence of ochratoxin A in cord serum and in human milk and its correspondence with maternal dietary habits, Eur. J. Nutr, 2011, 50(3), 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro CN, Tsimis M, Burd I, (2015). Infections and brain development. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv 70, 644–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciornea TE, Dumitru G, Coprean D, Mandalian LT, Boiangiu SR, Sandu I, Hritcu L (2019). Effect of Mycotoxins treatment on Oxidative Stress, Memory and Anxious Behavior in Zebrafish (Danio Renio). REV. CHIM (Bucharest), 70(3), 776–780 [Google Scholar]

- Davis AP, Grondin CJ, Johnson RJ, Sciaky D, McMorran R, Wiegers J, Wiegers TC, Mattingly CJ. (2019) The comparative toxicogenomics database: update 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D948–D954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis B, Brera C, Mezzelani A, Soricelli S, Ciceri F, Moretti G, Debegnach F, Bonaglia MC, Villa L, Molteni M, Raggi ME, (2017a). Role of mycotoxins in the pathobiology of autism: a first evidence. Nutr. Neurosci 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis B, Raggi ME, Moretti G, Facchiano F, Mezzelani A, Villa L, Bonfanti A, Campioni A, Rossi S, Camposeo S, Soricelli S, Moracci G, Debegnach F, Gregori E, Ciceri F, Milanesi L, Marabotti A, Brera C (2017b). Study on the association among mycotoxins and other variables in children with autism. Toxins 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis B Debegnach F, Miano B, Moretti G, Sonego E, Chiaretti A, Buonsenso D, Brera (2019). Determination of deoxynivalenol biomarkers in Italian urine samples. Toxins, 11, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, 2019- EFSA EU Insights - Chemical mixtures - Awareness, understanding and risk perceptions doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2019.EN-1602 [DOI]

- Fatemi SH, Pearce DA, Brooks AI, Sidwell RW, 2005. Prenatal viral infection in mouse causes differential expression of genes in brains of mouse progeny: a potential animal model for schizophrenia and autism. Synapse 57, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Huang H, Oishi K, Mori S, Smee DF, Pearce DA, Winter C, Sohr R, Juckel G, 2008. Maternal infection leads to abnormal gene regulation and brain atrophy in mouse offspring: implications for genesis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Schizophr. Res 99, 56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghallab A, Bolt HM (2014) In vitro systems: current limitations and future perspectives. Arch Toxicol (2014) 88:2085–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves RA, Naehrer K, Santos GA, 2018. Occurrence of mycotoxins in commercial aquafeeds in Asia and Europe: a real risk to aquaculture? Rev. Aquacult 10, 263e280. [Google Scholar]

- Hallen IP, Breitholtz-Emanuelsson A, Hult K, Olsen M and Oskarsson A, Placental and lactational transfer of ochratoxin A in rats, Nat. Toxins, 1998, 6(1), 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq M, Gonzalez N, Mintz K, Jaja-Chimedza A, De Jesus C, & Lydon C et al. (2016). Teratogenicity of Ochratoxin A and the Degradation Product, Ochratoxin α, in the Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryo Model of Vertebrate Development. Toxins, 8(2), 40. doi: 10.3390/toxins8020040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SX, Zheng Z, Chen X and Perrimon N, The Jak/ STAT pathway in model organisms:emerging roles in cell movement, Dev. Cell, 2002, 3(6), 765–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horzmann KA, Freeman JL. 2016. Zebrafish get connected: investigating neurotransmission targets and alterations in chemical toxicity. Toxics 4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC, 1993. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans 56, 489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JY, Kwon HB, Ahn JC, Kang D, Kwon SH, Park JA, Kim KW. 2008. Functional and developmental analysis of the blood-brain barrier in zebrafish. Brain Res Bull 75:619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan C, Covarelli L, Beccari G Colasante V, Manes J (2016) Simultaneous analysis of twenty-six mycotoxins in durum wheat grain from Italy. Food Control, 62, 322–329 [Google Scholar]

- Juan C, Berrada H, Mañes J, Oueslati S, 2017a. Multi-mycotoxin determination in barley and derived products from Tunisia and estimation of their dietary intake. Food Chem. Toxicol 103, 148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan C, Manes J, Font G, Juan-Garcia A (2017b) Determination of mycotoxins in fruit berry by-products using QuEChERS extraction method LWT-Food Science and Technology, 86, 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Juan C, Oueslati S, Mañes J, Berrada H (2019). Multimycotoxin determination in tunisian farm animal feed. Journal of Food Science doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan-García A, Manyes L, Ruiz MJ, Font G (2013). Applications of flow cytometry to toxicological mycotoxin effects in cultured mammalian cells: a review. Food Chem. Toxicol 56, 40–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan-García A, Juan C, Tolosa J, Ruiz MJ (2019a). Effects of deoxynivalenol, 3-acetyl-deoxynivalenol and 15-acetyl-deoxynivalenol on parameters associated with oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. Mycotox Research, 35, 2, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan-García A, Tolosa J, Juan C, Ruiz MJ (2019b). Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and disturbance of cell cycle in HepG2 cells exposed to OTA and BEA: single and combined actions. Toxins, 11, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan-García A, Carbone C, Ben-Mahmoud M, Sagratini G, Mañes J 2020. Beauvericin and ochratoxin A mycotoxins individually and combined in HepG2 cells alter lipid peroxidation, levels of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Food Chem Toxicol, 139, 111247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khezri A, Herranz-Jusdado J, Ropstad E, & Fraser T (2018). Mycotoxins induce developmental toxicity and behavioural aberrations in zebrafish larvae. Environmental Pollution, 242, 500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaric MK, Rumora L, Ljubanovic D, 2006. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by fumonisin B(1), beauvericin and ochratoxin A in porcine kidney PK15 cells: effects of individual and combined treatment. Arch. Toxicol 82, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C, Sanders G, Varga Z, Baumann D, Freeman A, Baur B, Francis M (2009), Regulatory Compliance and the Zebrafish, Zebrafish, 453–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvak J, 2003. Direct yolk sac volume manipulation of zebrafish embryos and the relationship between offspring size and yolk sac volume. J. Fish Biol 63, 388e397. [Google Scholar]

- Marijani E, Kigadye E, Okoth S (2019) Occurrence of Fungi and Mycotoxins in Fish Feeds and Their Impact on Fish Health International Journal of Microbiology, 10.1155/2019/6743065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Kuan M, Nestler S, Verguet C, Bezencon C, Piguet D, Mansourian R, Holzwarth J, Grigorov M, Delatour T, Mantle P, Cavin C, Schilter B (2006). A toxicogenomics approach to identify new plausible epigenetic mechanisms of ochratoxin a carcinogenicity in rat, Toxicol. Sci, 89 (1), 120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minervini F, Giannoccaro A, Nicassio M, Panzarini G, Lacalandra GM (2013). First evidence of placental transfer of ochratoxin A in horses, Toxins, 5 (1), 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthulakshmi S, Hamideh P, Habibi H, Maharajan K, Kadirvelu K, & Mudili V (2018a). Mycotoxin zearalenone induced gonadal impairment and altered gene expression in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis of adult female zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Applied Toxicology, 38(11), 1388–1397. doi: 10.1002/jat.3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthulakshmi S, Maharajan K, Habibi H, Kadirvelu K, & Venkataramana M (2018b). Zearalenone induced embryo and neurotoxicity in zebrafish model (Danio rerio): Role of oxidative stress revealed by a multi biomarker study. Chemosphere, 198, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak R, Ingram M, Marquez S, … (2020). Robotic fluidic coupling and interrogation of multiple vascularized organ chips doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0497-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oueslati S, Berrada H, Mañes J, Juan C (2017). Presence of mycotoxins in Tunisian infant foods samples and subsequent risk assessment. Food Control, 84, 362–369. [Google Scholar]

- OECD, 2013. Test No. 236: Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch C, Noser J, Wettstein F, & Burkhardt-Holm P (2014). Unraveling the mechanisms involved in zearalenone-mediated toxicity in permanent fish cell cultures. Toxicon, 88, 44–61. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch C, Kersten S, Burkhardt-Holm P, Valenta H, Daenicke S, 2013. Occurrence of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone in commercial fish feed: an initial study. Toxins 5, 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rico EP, Rosemberg DB, Seibt KJ, Capiotti KM, Da Silva RS, Bonan CD. 2011. Zebrafish neurotransmitter systems as potential pharmacological and toxicological targets. Neurotoxicol Teratol 33, 608–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge EJ, Sumpter JP. Estrogenic activity of surfactants and some of their degradation products assessed using a recombinant yeast screen. Environ Toxicol Chem 1996, 241–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sanden M, Jorgensen S, Hemre GI, Ornsrud R, Sissener NH (2012) Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model for investigating dietary toxic effects of deoxynivalenol contamination in aquaculture feeds. Food Chem Toxicol, 50, 4441–4448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H 2017. Zebrafish neurobehavioral assays for drug addiction research In: Kalueff AV, editor. The rights and wrongs of zebrafish: behavioral phenotyping of zebrafish Cham: Springer International Publishing; 171–205. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P, Thorpe K, Bucheli T, Wettstein F, & Burkhardt-Holm P (2010). Short-term exposure to the environmentally relevant estrogenic mycotoxin zearalenone impairs reproduction in fish. Science Of The Total Environment, 409(2), 326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P, Bucheli T, Wettstein F, & Burkhardt-Holm P (2011). Life-cycle exposure to the estrogenic mycotoxin zearalenone affects zebrafish (Danio rerio) development and reproduction. Environmental Toxicology, 28(5), 276–289. doi: 10.1002/tox.20718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu O, Juan C, Miere D, Loghin F, Mañes J, 2017. Presence of enniatins and beauvericin in Romanian wheat samples: from raw material to products for direct human consumption. Toxins 9, 189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu O, Juan C, Miere D, Berrada H, Loghin F, Mañes J (2018). First study on trichothecene and zearalenone exposure of the Romanian population through wheat-based products consumption. Food Chem. Toxicol, 121, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirado MC, Clarke R, Jaykus LA, McQuatters-Gollop A, Frank JM. Climate change and food safety: A review. Food Research International, 43, 1745–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Tschirren L, Siebenmann S, Pietsch C (2018). Toxicity of Ochratoxin to Early Life Stages of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxins, 10(7), 264. doi: 10.3390/toxins10070264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mycotoxins

- Wu T, Cheng Y, Chen P, Huang Y, Yu F, Liu B (2019). Exposure to aflatoxin B1 interferes with locomotion and neural development in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Chemosphere, 217, 905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Yang J, Wang Y, Yu F, Liu B (2016). Mycotoxin ochratoxin A disrupts renal development via a miR-731/prolactin receptor axis in zebrafish. Toxicology Research, 5(2), 519–529. doi: 10.1039/c5tx00360a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Lin Y, Huang Y, Cheng Y, Yu F, Liu B (2018). Disruption of liver development and coagulation pathway by ochratoxin A in embryonic zebrafish. Toxicology Applied Pharmacology, 340, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhang N, Li Y, Zhao L, Yang M, Jin Y et al. (2017). Citrinin exposure affects oocyte maturation and embryo development by inducing oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis. Oncotarget, 8(21). doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Yang J, Yu F, & Liu B (2013). Cardiotoxicity of mycotoxin citrinin andiInvolvement of microRNA-138 in zebrafish embryos. Toxicological Sciences, 136(2), 402–412. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zain ME, 2011. Impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. J. of Saudi Chemical Society 15, 2, 129–144 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, George S, Li C, Gurusamy S, Sun X, Gong Z, & Qian H (2017). Combined toxicity of prevalent mycotoxins studied in fish cell line and zebrafish larvae revealed that type of interactions is dose-dependent. Aquatic Toxicology, 193, 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]