Abstract

Purpose

Aim of the study is to evaluate the incidence of DVT in COVID-19 patients and its correlation with the severity of the disease and with clinical and laboratory findings.

Methods

234 symptomatic patients with COVID-19, diagnosed according to the World Health Organization guidelines, were included in the study. The severity of the disease was classified as moderate, severe and critical. Doppler ultrasound (DUS) was performed in all patients. DUS findings, clinical, laboratory’s and therapeutic variables were investigated by contingency tables, Pearson chi square test and by Student t test and Fisher's exact test. ROC curve analysis was applied to study significant continuous variables.

Results

Overall incidence of DVT was 10.7% (25/234): 1.6% (1/60) among moderate cases, 13.8% (24/174) in severely and critically ill patients. Prolonged bedrest and intensive care unit admission were significantly associated with the presence of DVT (19.7%). Fraction of inspired oxygen, P/F ratio, respiratory rate, heparin administration, D-dimer, IL-6, ferritin and CRP showed correlation with DVT.

Conclusion

DUS may be considered a useful and valid tool for early identification of DVT. In less severely affected patients, DUS as screening of DVT might be unnecessary. High rate of DVT found in severe patients and its correlation with respiratory parameters and some significant laboratory findings suggests that these can be used as a screening tool for patients who should be getting DUS.

Keywords: Venous thrombosis, Ultrasonography, Doppler; diagnosis, COVID-19, Pandemics

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurred in 3.5% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients and 1.3% in hospitalized patient in medicine wards [1, 2].

A hallmark of patients affected by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is coagulopathy.

Mechanism and pathogenesis is still not clear, although excessive inflammation, hypoxia, immobilization and diffuse intravascular coagulation could be possible factors associated with high incidence of thromboembolism [3, 4].

Clinical observations stemming from patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) showed that several patients have signs of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) [5, 6].

The purpose of this study was to explore the incidence of DVT in COVID-19 patients and correlate it with the severity of the disease as well as with clinical and laboratory findings.

Materials and methods

A total number of 234 patients, with the mean age of 61.63 years, including 164 females (70%) and 70 males (30%), diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 admitted in our Hospital from March 15th and April 7th 2020 were included in our study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables list and descriptive statistics

| Continuous variables | N | Min | Max | Mean | standard dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 234 | 7 | 98 | 61.63 | 14.21 |

| BMI (kg /m2) | 56 | 23.15 | 42.9 | 29.08 | 5.14 |

| Time from symptoms onset (days) | 228 | 0 | 36 | 7.21 | 4.63 |

| Admission to DUS time (days) | 233 | 0 | 34 | 10.14 | 8.29 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 233 | 90 | 180 | 130.03 | 17.43 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 233 | 45 | 100 | 73.57 | 11.06 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 234 | 40 | 130 | 80.19 | 15.05 |

| FiO2 | 165 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| SpO2 | 231 | 0.95 | 100 | 95.55 | 6.97 |

| PF ratio | 195 | 57 | 472 | 225.45 | 97.51 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 232 | 12 | 40 | 21.69 | 4.88 |

| Platelet (cells/mm3) | 233 | 45 | 812 | 328.28 | 145.40 |

| INR | 229 | 0.044 | 4.3 | 1.18 | 0.33 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 231 | 1.01 | 77.9 | 34.01 | 7.49 |

| D-dimer (µg/mL) | 229 | 200 | 90681 | 4006.0 | 8900.1 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 209 | 120 | 1139 | 509.14 | 190.62 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 68 | 1.5 | 543 | 59.09 | 90.95 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 228 | 69.4 | 15033 | 1278.38 | 1627.82 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 232 | 0 | 34.15 | 5.74 | 6.50 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 153 | 0.02 | 40.8 | 0.61 | 3.37 |

| Heparin dosage (UI) | 202 | 2850 | 12500 | 5653.22 | 1799.23 |

| Categorical variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 70 | 29.90 |

| Female | 164 | 70.10 |

| Smoke | ||

| Yes | 203 | 86.75 |

| No | 26 | 11.11 |

| COPD | ||

| Yes | 18 | 7.69 |

| No | 211 | 90.17 |

| Asthma | ||

| Yes | 10 | 4.27 |

| No | 219 | 93.59 |

| Fever | ||

| Yes | 207 | 88.46 |

| No | 25 | 10.68 |

| Cough | ||

| Yes | 141 | 60.26 |

| No | 89 | 38.03 |

| Dyspnea | ||

| Yes | 156 | 66.67 |

| No | 76 | 32.48 |

| Chest pain | ||

| Yes | 6 | 2.56 |

| No | 224 | 95.73 |

| Other symptoms | ||

| Yes | 100 | 42.74 |

| No | 134 | 57.26 |

| Asthenia | ||

| Yes | 29 | 12.39 |

| No | 205 | 87.61 |

| Myalgia | 100.00 | |

| Yes | 12 | 5.13 |

| No | 222 | 94.87 |

| Gastroenteric symptoms | ||

| Yes | 32 | 13.68 |

| No | 202 | 86.32 |

| Alteration of consciousness | ||

| Yes | 16 | 6.84 |

| No | 218 | 93.16 |

| Upper airways symptoms | ||

| Yes | 10 | 4.27 |

| No | 224 | 95.73 |

| Deep vein thrombosis risk factors | ||

| Yes | 42 | 17.95 |

| No | 192 | 82.05 |

| Cancer | ||

| Yes | 26 | 11.11 |

| No | 208 | 88.89 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||

| Yes | 138 | 58.97 |

| No | 96 | 41.03 |

| Obesity | ||

| Yes | 37 | 15.81 |

| No | 197 | 84.19 |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 93 | 39.74 |

| No | 141 | 60.26 |

| Ischemic heart disease | ||

| Yes | 17 | 7.26 |

| No | 217 | 92.74 |

| Myocardial infarction | ||

| Yes | 8 | 3.42 |

| No | 226 | 96.58 |

| Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 40 | 17.09 |

| No | 194 | 82.91 |

| Dyslipidemia | ||

| Yes | 23 | 9.83 |

| No | 211 | 90.17 |

| Prolonged bed rest | ||

| Yes | 152 | 64.96 |

| No | 82 | 35.04 |

| Venous catheter | ||

| Yes | 15 | 6.41 |

| No | 219 | 93.59 |

| Ward type | ||

| High intensity of care | 46 | 19.66 |

| Mid-intensity of care | 128 | 54.70 |

| Low intensity of care | 60 | 25.64 |

| O2 therapy | ||

| Nasal cannula | 29 | 12.39 |

| Venturi/reservoir | 42 | 17.95 |

| C-PAP | 85 | 36.32 |

| Orotracheal intubation | 78 | 33.33 |

| Heparin administration | ||

| q24 h | 101 | 43.16 |

| q12 h | 125 | 53.42 |

| q8 h | 8 | 3.42 |

All the patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [7]. These patients underwent a series of investigations, including clinical examinations, laboratory tests, chest X-ray (CXR), sometimes computed tomography (CT), and real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2. The severity of the disease of the hospitalized patients was judged according to the Seventh Revised Edition of the “The diagnosis and treatment plan for the novel coronavirus disease” [8] in moderate, severe and critical disease, and patients were sorted in Low intensity care units (LICU), Mid-intensive Care Units (MICU) and Intensive Care Units (ICU), respectively.

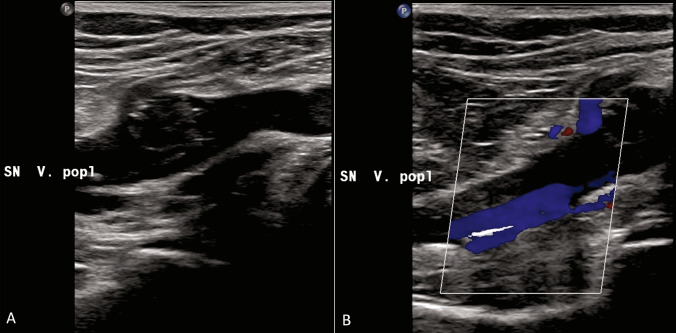

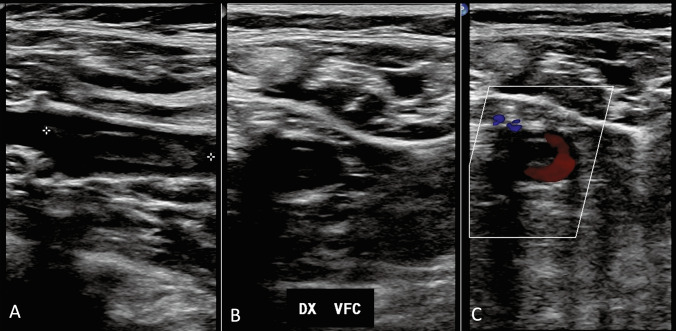

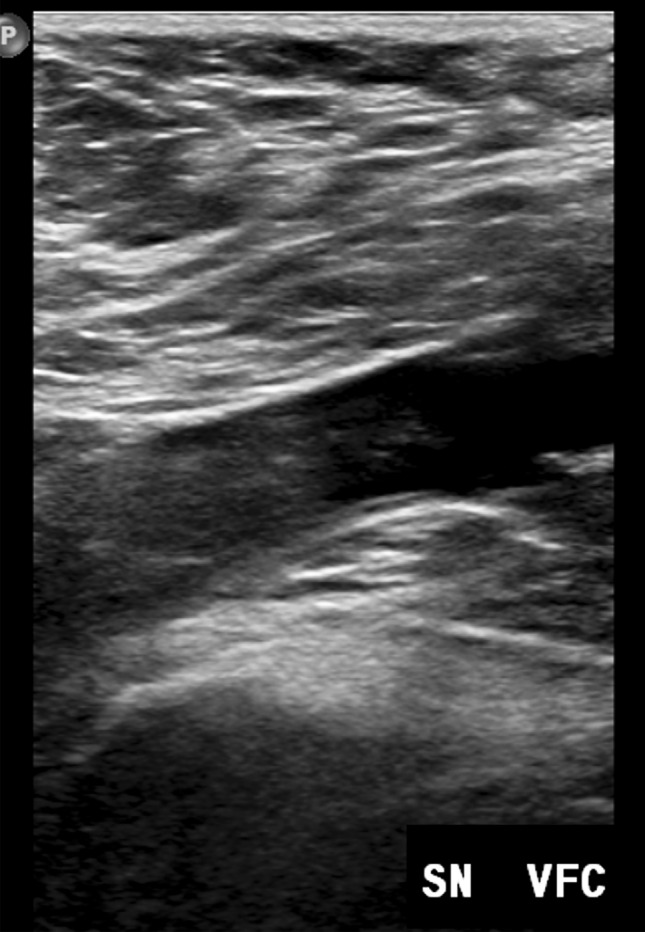

All patients were asymptomatic and were underwent to Doppler ultrasound (DUS) examination. Two skilled operators performed the bedside examinations, with portable US machines available in each ward and using the linear probe (Fig. 1). DUS findings were classified as positive or negative; femoral and/or popliteal thrombosis was considered as positive DVT (Figs. 2a, b, 3a, b, c).

Fig. 1.

Thrombosis of the common femoral vein

Fig. 2.

A, B: Partial thrombosis of the popliteal vein

Fig. 3.

a, b, c Floating thrombus of the common femoral vein

All the continuous and categorical variables analyzed are summarized in Table 1 and include clinical, laboratory’s and therapeutic factors. Each patient needed oxygen (O2) therapy and was treated at least with prophylactic heparin administration (Table 1).

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. No informed consent was required.

The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (Radcovid03/2020).

SPSS v25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses; p values were considered significant when < 0.05.

A correlation between the DUS result (positive/negative) and many clinical, laboratory’s and therapeutic variables (see Table 1 for variables list) was investigated by contingency tables and Pearson chi square test for categorical variables and by Student t test and Fisher's exact test for continuous variables. Continuous variables that showed a significant correlation were studied also with ROC curve analysis.

Results

The 234 patients included in the study were hospitalized as follows: 46 in ICU, 128 in MICU and 60 in LICU (Table 1).

At DUS, asymptomatic DVT finding was reported in 25/234 cases (10.7%). Contingency tables and Pearson chi square test showed a good association for prolonged bedrest and ward type. Only 2 out of 82 were self-mobilizing versus 23 out of 152 bedrest patients showed DVT on DUS (sensitivity: 92.0%; specificity: 38.3%; p value: 0.003). Moreover, only 1 out of 60 low-intensity care wards patients (1.6%) versus 15 out of 128 mid-intensity care wards (11.7%) and 9 out of 46 high-intensity care wards patients (19.6%) showed DVT on DUS (chi square 9.05; p value: 0.01).

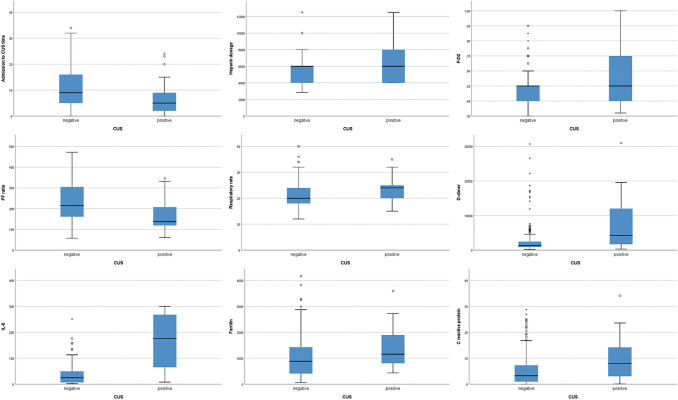

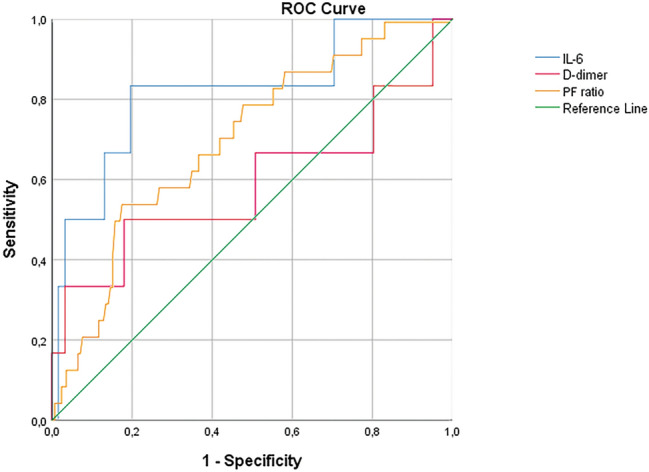

Student t test and Fisher's exact test showed good associations for ventilation, therapeutic and laboratory’s variables. More in detail, deep vein thrombosis was found in patients with an higher fraction of inspired oxygen (p value: 0.002), a lower P/F ratio (p value: 0.0007) and an higher respiratory rate (p value: 0.049); moreover, in these patients heparin dosage was higher, despite number of administration per day (q24 h / q12 h / q8 h). Higher values of d-dimer (p value: 0.000004) and IL-6 levels (p value: 0.002), higher ferritin (p value: 0.01), and higher C reactive protein (p value: 0.004) were found in patients with DVT compared with those without DVT. Moreover, time between hospital admission and DUS was lower in DVT patients (p value: 0.03). Details are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 4. ROC curve (Table 3 and Fig. 5) showed the highest AUC for IL-6 (0.820) with a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 80.6% for a cutoff of 64.95 pg/mL, with an accuracy (AUC) of 82.0%.

Table 2.

Student t test results

| T test | p value | Mean ± SD DVT |

Mean ± SD DVT negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | > 0.05 | 65 ± 10.28 | 61.22 ± 14.57 |

| BMI | > 0.05 | 27.23 ± 5.24 | 29.59 ± 5.05 |

| Time from symptoms onset | > 0.05 | 7.92 ± 4.62 | 7.12 ± 4.63 |

| Admission to DUS time | 0.029 | 6.6 ± 8.13 | 10.56 ± 8.22 |

| Systolic blood pressure | > 0.05 | 130.64 ± 15.9 | 129.96 ± 17.64 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | > 0.05 | 70.84 ± 11.28 | 73.9 ± 11.02 |

| Heart rate | > 0.05 | 80.36 ± 17.85 | 80.17 ± 14.73 |

| FiO2 | 0.0019 | 0.58 ± 0.2 | 0.48 ± 0.13 |

| SpO2 | > 0.05 | 94.71 ± 2.87 | 95.64 ± 7.3 |

| PF ratio | 0.00072 | 168.54 ± 77.4 | 233.44 ± 97.56 |

| Respiratory rate | 0.049 | 23.48 ± 4.6 | 21.48 ± 4.88 |

| Platelet | > 0.05 | 288.8 ± 180.97 | 333.03 ± 140.31 |

| INR | > 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.24 | 1.18 ± 0.34 |

| Partial thromboplastin time | > 0.05 | 34 ± 6.34 | 34.01 ± 7.63 |

| D-dimer | 0.000004 | 11571.92 ± 20404.55 | 3078.75 ± 5641.83 |

| Fibrinogen | > 0.05 | 527.88 ± 250.82 | 506.59 ± 181.64 |

| IL-6 | 0.0021 | 165.48 ± 121.76 | 48.79 ± 81.55 |

| Ferritin | 0.010 | 2080.04 ± 2988.36 | 1184.07 ± 1366.14 |

| C reactive protein | 0.0042 | 9.23 ± 8.42 | 5.32 ± 6.12 |

| Procalcitonin | > 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.41 | 0.63 ± 3.56 |

| Heparin dosage | 0.035 | 6433.33 ± 2256.84 | 5562.71 ± 1723.29 |

SD Standard Deviation; BMI Body Mass Index; FiO2 Fraction of inspired oxygen; SPO2 peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; PF ratio PaO2/FiO2 ratio; INR international normalized ratio

Fig. 4.

Boxplot for significant continuous variables

Table 3.

ROC curve analysis for significant continuous variables at student t test

| Variable | AUC | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission to DUS time (days) | 0.661 | 9.5 | 0.760 | 0.490 |

| Heparin dosage (UI) | 0.611 | 5350 | 0.619 | 0.470 |

| FiO2 | 0.638 | 0.525 | 0.478 | 0.768 |

| PF ratio | 0.701 | 292.5 | 0.917 | 0.292 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 0.637 | 19 | 0.880 | 0.314 |

| D-dimer (µg/mL) | 0.707 | 2128 | 0.680 | 0.706 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 0.820 | 64.95 | 0.833 | 0.806 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 0.663 | 907.5 | 0.708 | 0.515 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.659 | 4.1 | 0.720 | 0.570 |

Fig. 5.

ROC curve for significant continuous variables with AUC > 0.7

Discussion

Apart from respiratory failure, coagulopathy is a common abnormality in patients with COVID-19.

Klok FA et al. [3] reported a high incidence of thrombotic complications (acute pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction or systemic arterial embolism) in patients with COVID-19 infections (31%) admitted at ICU. All patients received at least standard doses thromboprophylaxis.

Data about the incidence of DVT is scarce. A recent published study has shown an incidence of 25% of DVT in ICU COVID-19 patients; the significant increase of D-dimer resulted as a good index for identifying high-risk patients [5].

Llitjos JF et al. reported 69% incidence rate of DVT in severe mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients; all patients were treated with therapeutic anticoagulation from admission [6].

Even in our Hospital, from the beginning of the outbreak, an unusually high mortality rate due to pulmonary embolism occurred among hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were under prophylactic dose of low molecular weight heparin. Therefore, we decided to implement a screening program for DVT in COVID-19 patients hospitalized.

We found that DVT even occurs in patients treated with therapeutic anticoagulation from admission, highlighting the high thromboembolic potential of COVID19. Bedrest and ICU admission resulted significantly associated with the presence of DVT.

Our results have shown an incidence for DVT of 10.7%, lower than in other mentioned publications. The reason is to be found in the fact that our study is the only one in which even patients less severely affected from low intensity wards were included. In medicine wards we found only 1 out of 60 hospitalized patients, with an incidence of 1.6%, similar to that reported in the same wards in non-COVID-19 patients (1.3%) [1, 9, 10]. This observation led us to suppose that in less severely affected patients in low-intensity Covid-19 wards, execution of DUS as screening of DVT might be unnecessary. Our overall incidence of DVT increases to 13.8% considering mid-and high-intensity Covid-19 units (24/174).

Strengths of the present study is represented by the large analyzed series, which to date, is the largest in literature. Moreover, an association with clinical, laboratory’s and therapeutic parameters was investigated and confirmed for the first time. Indeed, both the fraction of inspired oxygen, P/F ratio and the respiratory rate and heparin administration, d-dimer, IL-6, ferritin and CRP resulted correlated with the presence of DVT.

However, the study presents some limitations, especially in its retrospective design. Moreover, DUS was performed earlier in DVT patients and DVT patients had an higher dose of heparin, so an underestimation of DVT may be suspected in some cases. This suggests that clinical and laboratory suspicion before investigation is always mandatory.

The high rate of DVT found in our severe COVID-19 patients who were under prophylactic treatment and correlation with respiratory parameters and some significant laboratory findings suggests that these can be used as a screening tool for patients who should be getting DUS [11]. In these patients, DUS may be considered a useful and valid tool for early identification of DVT.

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- AUC

Area under the curve

- WHO

World Health Organization

- O2

Oxygen

- COVID 19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CXR

Chest X-ray

- CT

Computed tomography

- rRT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- LICU

Low-intensity care unit

- MICU

Mid-intensive care unit

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its late amendments. The study protocol was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study.

Consent for publication

All authors expressed explicit consent for the publication of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miri M, Goharani R, Sistanizad M. Deep vein thrombosis among intensive care unit patients; an epidemiologic study. Emerg (Tehran) 2017;5(1):e13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein PD, Beemath A, Olson RE. Trends in the incidence of pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in hospitalized patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(12):1525–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marone EM, Rinaldi LF. Upsurge of deep venous thrombosis in patients affected by COVID-19: Preliminary data and possible. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llitjos JF, Leclerc M, Chochois C, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases. Interim guidance (2020). https://www.who.int/publications-detail/laboratory-testing-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-in-suspected-human-cases-20200117

- 8.National Health Commission of China (2020) The diagnosis and treatment plan for the novel coronavirus disease (the seventh edition). https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/pdf/2020/1.Clinical.Protocols.for.the.Diagnosis.and.Treatment.of.COVID-19.V7.pdf

- 9.Becciolini M, Galletti S, Vallone G, Stella SM, Ricci V. Sonographic diagnosis of clinically unsuspected thrombosis of the medial marginal vein and dorsal arch of the foot. J Ultrasound. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00421-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malerba P, Kaminstein D, Brunetti E, Manciulli T. Is there a role for bedside ultrasound in malaria? A survey of the literature. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tung-Chen Y, Pizarro I, Rivera-Núñez MA, et al. Sonographic evolution of the superficial vein thrombosis of the lower extremity. J Ultrasound. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00482-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]