Abstract

Phytophthora capsici is a notorious fungus which infects many crop plants at their early and late growth stages. In the present study, twelve P. capsici isolates were morphologically characterized, and based on pathogenicity assays; two highly virulent isolates causing post-emergence damping-off on locally cultivated chilli pepper were screened. Two P. capsici isolates, HydPak1 (MF322868) and HydPk2 (MF322869) were identified based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence homology. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) play a significant role in disease suppression and plant growth promotion in various crops. Out of fifteen bacterial strains recovered from chilli rhizosphere, eight were found potential antagonists to P. capsici in vitro. Bacterial strains with strong antifungal potential were subjected to biochemical and molecular analysis. All tested bacterial strains, were positive for hydrogen cyanide (HCN), catalase production and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production (ranging from 6.10 to 56.23 µg ml−1), while siderophore production varied between 12.5 and 33.5%. The 16S rRNA sequence analysis of tested bacterial strains showed 98–100% identity with Pseudomonas putida, P. libanensis, P. aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, B. megaterium, and B. cereus sequences available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank nucleotide database. All sequences of identified bacteria were submitted to GenBank for accessions numbers (MH796347-50, MH796355-56, MH801129 and MH801071). Greenhouse studies concluded that all tested bacterial strains significantly suppressed the P. capsici infections (52.3–63%) and enhanced the plant growth characters in chilli pepper. Efficacy of many of these tested rhizobacteria is being first time reported against P. capsici from Pakistan. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) exhibiting multiple traits may be used in the development of new, eco-friendly, and effective bioformulations as an alternative to synthetic fungicides.

Subject terms: Biotic, Microbe, Biotic, Microbe

Introduction

Chilli, also red pepper or chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is among the extensively grown spice crop in Pakistan like many other countries around the globe. Quality and quantity of the crop are adversely affected by numerous soil-borne and areal pathogens of which Phytophthora capsici is one of the most devastating oomycete pathogens, resulting into damping-off and blight diseases1. This pathogen causes complete crop failure under favorable environmental conditions2. Synthetic pesticides are frequently applied to attain a high yield of the produce however, this disease management strategy comes with potential risks to the environment and human health3. Soil-borne nature of oomycete agents makes them more difficult to control due to longterm surviving potential in the soil4.

In the rhizosphere, bacteria are abundant microbes within the soil, and many of them have plant growth promotion traits known as PGPRs5. Their mechanism of action includes the production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), nitrogen fixation, soil phosphorus solubilization and various nutrients, and antagonism against pathogens by siderophores, cellulose, protease, antibiotics and cyanide production6. Many scientists have reported the growth promotion in cereal crops7, fruits8, vegetables9 including pepper10 by the application of rhizobacteria.

Bacterial strains belonging to Actinobacteria, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces spp. are declared as biological control agents of P. capsici and suppress damping-off disease in various crops11–13. Because of the undesirable features of synthetic agrochemicals and increasing threat to the environment, utilization of naturally occurring biological control agents for disease suppression and plant growth enhancement is one of the possible alternatives. The present study is designed to isolate, characterize, to test the disease suppressiveness and PGP effects of native rhizobacterial strains, recovered from chilli rhizosphere. This study will help to explore the potential of these bacterial strains against other soil-borne pathogens and bio-pesticide development.

Materials and methods

Isolation and pathogenicity of Phytophthora capsici

During two years survey in chilli paper growing fields in February–November, 2016–2017, young symptomatic seedlings (15–30 days old) showing post-emergence damping-off symptoms were collected. Damping-off was confirmed by carefully observing the rotten roots1 and symptomatic roots showing typical browning and necrosis were collected in zip polythene bags, properly labelled, and kept in an icebox. All the collected samples were brought to the Department of Plant Pathology, PMAS Arid Agriculture University for further processing. Infected roots were surface disinfected in 0.1% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min followed by three consecutive washings in sterilized distilled water (SDW). Root tissues were cut into small slices (0.5 mm), and were placed aseptically on Petri plates containing P. capsici selective CMA-PARPH medium (Corn meal agar, 17 g; pimaricin, 10 mg; ampicillin, 250 mg; rifampicin, 10 mg; PCNB, 100 mg; hymexazol, 50 mg; and distilled water, 1,000 ml)14. All the Petri dishes were sealed with Parafilm tape, labelled with isolate code, data of isolation, and were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 7 days. A total of 12 P. capsici isolates were recovered and maintained on PDA medium amended with rifamycin (5 mg l−1).

Pathogenicity assay was conducted on seeds of two locally available chilli varieties (Long Green and Neelam) in vitro. Prior to seed sowing, already disinfected soil was flooded with 20 ml sporangial suspension (1 × 103 sporangia ml−1) of P. capsici in 1.5 l capacity plastic pots. Seeds of both the varieties were surface sterilized and sown in infected soil (10 seeds/pot) in five repeats for each test fungal strain in a repeated experiment and un-inoculated pots were served as control. All the pots were kept 25 ± 2 °C up to 20 days. Seedling mortality percentage was observed 15 days after sowing. Re-isolation of P. capsici from the infected root samples confirmed the association of the pathogen with the chilli damping off disease.

Characterization of Phytophthora capsici

Phytophthora capsici was identified based on morphological characteristics. For sporangial production, small discs (5-mm) from actively growing mycelia were cultured on V8-agar medium containing Petri plates under white fluorescent light at 26 ± 2 °C for 7 days15. Sterile distilled water (SDW) was added to each Petri plate, shaken to detach sporangia, and poured on a glass slide. Glass slide was covered with a coverslip and was examined under a compound microscope. Sporangial shape and size were measured at 200 × magnification while pedicle length was measured at 100 × magnification16 for 20 randomly chosen sporangia from each isolate. Chlamydospores production was studied in accordance with Ristaino15. Briefly, actively growing P. capsici was aseptically transferred to 25 ml of clarified V8 broth (C-V8, 163 ml clarified V8 juice, 3 g CaCO3, 1,000 ml distilled water, 86 mg ampicillin, 26 mg rifampicin) in a sterilized 50 ml lid containing tube, and incubated in the dark at 26 ± 2 °C for 24 h. After incubation, tubes were shaken for 5 min and were incubated in the dark for 5 days. C-V8 broth was replaced with 45 ml of SDW, followed by incubation in the dark at 18 ± 2 °C for 72 h. Chlamydospores were detached from mycelium using sterilized forceps and a dissecting needle and were observed under 100X magnification.

Two highly virulent P. capsici strains (HydPk1 and HydPk2) confirmed in Pathogenicity assays were subjected to molecular based identification. Genomic DNA was extracted by using the standard protocol of Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB)17,18. The internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS1 and ITS2) of the genomic DNA were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using universal sense ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) encoding ITS-1–5.8S-ITS-219,20. Reaction was carried out in 50 μl total reaction mixture volumes containing 33·25 μl grade water, 5 μl PCR (10X) buffer, 4 μl dNTPs (5 Mm each), 1·5 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 μl each of ITS1 and IT4 primers (20 pmol), 0·25 μl (0·5 U) Taq DNA polymerase and 2 μl DNA as a template. PCR conditions were 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 2 min and a final elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR amplified products were analyzed in 2% agarose gel (high resolution agarose, Q-BIOgen) in TAE buffer containing 40 mmol l−1 Tris–HCl (pH 7.9), 4 mmol l−1 sodium acetate, and 1 mmol l−1 EDTA (pH 7.9). The purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions and sequences were assembled to create a final sequence for each tested isolate. Basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) analysis was performed to check the sequence similarities of the tested sequences with those already deposited sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). All the retrieved and tested sequences were aligned using ClustalW program and subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method in MEGA-X version 10.1.7 with 1,000 bootstrap replications and the evolutionary distances were calculated by using Jukes–Cantor model. Sequences were submitted to NCBI and accession numbers were obtained.

Isolation of PGPR strains

Soil sampling

Rhizospheric soil samples along with healthy roots were collected from the chilli pepper fields in Rawalpindi division, Pakistan (33.5651° N, 73.0169° E). Samples were labelled properly and shifted to the icebox for transportation to Plant Bacteriology Laboratory, Department of Plant Pathology, PMAS Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi and preserved at 4 °C till further use for the isolation of rhizobacterial strains.

Bacterial isolation and preservation

The Serial dilution procedure described by Xu and Kim3 was adopted for the isolation of rhizobacterial strains. One gram (1 g) of the rhizosphere soil from each sample, strongly adhering to the roots was poured separately in a test tube containing 9 ml sterile distilled water (10−1) and vortexed vigorously for 10 min. Subsequently, serial dilutions (from 10−1 to 10−8) were made. For the isolation of Bacillus spp., 100 μl of each dilution was poured on Nutrient agar (NA, Difco, USA) plates, while Pseudomonas spp. were isolated on Kings’ B medium incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h. Pure bacterial cultures were obtained by picking up a single discrete bacterial colony on freshly prepared NA medium plates and a total of fifteen bacterial isolates were recovered (Table 1). Obtained isolates were stored at − 80 °C in 40% glycerol and distilled water solution21 until further use in experiments.

Table 1.

List of rhizobacterial strains isolated from chilli pepper fields from three different locations in Rawalpindi District, Pakistan.

| S. no. | Isolates code | No. of strains | Crop | Location | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AJ-RB22, AJ-RB13, JHL 3, JHL 4, JHL 8, JHL-12 | 6 | Chilli pepper | Adiiyala Jhamra | 33.4573° N, 72.9948° E |

| 2 | KSL-8T, KSL-24, RWPRB03, 4a2, RH-87, 5C | 6 | Chilli pepper | Kasala | 15.4581° N, 36.4040° E |

| 3 | DKB53, RB09, RBT7 | 3 | Chilli pepper | Dhok Bawa | 33.4739° N, 73.0206° E |

Antagonism assay against P. capsici in vitro

Bacterial strains were screened in vitro for antagonism against P. capsici. Rhizobacterial cultures were re-streaked on NA medium 48 h before testing their antagonistic potential in dual culture22. A seven days old culture of HydPk2—P. capsici (accession MF322869) on potato dextrose agar (PDA) was used in this experiment. Briefly, 5 mm fungal mycelial plugs were cultured in the center of PDA Petri plates and bacterial cultures were streaked on both sides of the fungal plugs at a 2 cm of distance. Controls consisted of single cultures of the tested pathogen strain/s. Bacterial antagonism was tested in triplicate and plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for about 96 h. The antagonistic potential was evaluated as inhibition of the mycelial radial growth of P. capsici against each bacterial strain tested. The experiment was carried out under a complete randomized design (CRD) with three replications.

where R and r is the radius of fungal mycelial growth in control and treatment, respectively.

Biochemical features of the obtained rhizobacterial strains

Ammonia (NH3) production test

The Ammonia (NH3) production test was performed in accordance with Dye23. In particular, the test tubes containing peptone water (10.0 g peptone; 5.0 g NaCl; 1,000 ml distilled water; 7.0 pH) were inoculated with 100 μl of 24 h grown bacterial cultures in nutrient broth medium and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 48–72 h. The ammonia production was detected by adding Nessler's reagent (0.5 ml) in each test tube. The production of a brown to the deep yellow colour indicated NH3 production.

Hydrogen cyanide production

Hydrocyanic acid (HCN) production was evaluated according to24 with a modification in the procedure. In particular, 24 h bacterial cultures grown in nutrient broth medium were inoculated on TSA medium amended with 4.4 g l−1 glycine in Petri plates. Filter papers soaked in the picric acid solution (0.5% picric acid, 2% sodium carbonate) were put into lids of each Petri plate. These Petri plates were properly sealed with Parafilm and inoculated for 2 to 4 days at 28 ± 2 °C. After incubation for 48 h at 28 ± 2 °C, filter papers were observed for colour changes from weak yellow to reddish brown for each of the bacterial strain; indicating the positive test results.

Catalase test

Catalase test was carried out following Hayward25. In particular, freshly grown (24 h old) bacterial culture on NA medium was placed on a dry glass slide and one drop of 3% H2O2 was dropped on the bacterial colony. Rapid gas bubbles formation indicated the positive test results for the tested bacterial strains.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) solubility test

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) solubility test was determined by following the procedure adopted by KIrsop and Doyle26. A loopful of 24 h old bacterial culture grown on NA medium was mixed with 3% Potassium Hydroxide solution on a dry glass slide till even suspension is formed. Formation of mucoid thread (loop) confirmed the positive reaction for the tested bacterial strains.

IAA production assay

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production in rhizobacteria was tested in accordance with Dasri, et al.27. Each rhizobacterial strain was suspended in distilled water at (108 CFU ml−1) (OD620 = 0.1), then 0.5 ml aliquots were inoculated into 50 ml of King's B broth amended with 0.1% l-tryptophan followed by incubation at 28 °C for 72 h. Cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and then 2 ml supernatant was thoroughly mixed with 4 ml of Salkowski reagent (1 ml of 0.5 M FeCl3 solution in 50 ml of 35% perchloric acid). Change in the colour pink to red indicated the production of IAA. Optical density (OD) was measured at 530 nm by using a spectrophotometer, and IAA concentration was determined in comparison to 10–100 µg ml−1 IAA standard curve. There were three replications for each bacterial strain to confirm the test results, and mean values were statistically analyzed.

Siderophore production

Siderophore production was assessed by culturing the bacterial strains on Chrome azurol S (CAS) agar. All the tested bacterial cultures were incubated 28 ± 2 °C for 5–7 days and the siderophore production was detected by the development of a yellow-orange halo around the bacterial colonies28. For each strain, the siderophore production was quantified by CAS-liquid assay by mixing the bacterial culture supernatant (0.5 ml) with 0.5 ml of CAS reagent. Absorption was measured at 630 nm over a control treatment made of 0.5 ml of non-inoculated broth medium mixed with 0.5 ml of CAS reagent. There were three replications for each bacterial strain to confirm the test results, mean values were calculated, and data was statistically analyzed.

Molecular-based identification of rhizobacterial strains

Total genomic DNA of rhizobacterial strains was isolated using GeneJet Genomic DNA purification Kit (Thermo Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial strains were identified by amplifying 16S rRNA region by PCR using a set of universal primers; 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3)29,30. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction was carried out by using the standard reaction mixture (100 µl) containing: 5 × PCR buffer, 25 mM Mgcl2, 10 mM of each dNTPs, 4 µl of each primer (0.5 µM), 1 µl of Taq Polymerase enzyme (0.5 U µl−1), and 2 µl of bacterial DNA template. PCR conditions for 16S rRNA gene amplification were: initial denaturation of DNA template at 95 °C for 1 min per cycle, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 15 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min and final elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR amplified products were examined by separating the product on 1% agarose gel and visualized under UV transilluminator. Gel photographs were taken by using a gel documentation system. Amplified PCR product (1.5 kb) was purified using Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) and DNA quantification was carried out using NanoDrop. The amplified products were then sent to the Crop Science Department, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, USA for sequencing. Final sequences were obtained by joining both the reverse and forward sequences, and the 16S rRNA sequences of the bacterial strains were submitted in the GenBank database to obtain accession numbers (Table 2). The similarity between the sequences was checked by aligning test sequences, and their best-matched sequences (on average 4 to 5 sequences) available in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank nucleotide database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using ClusterW program. The nucleotide sequence homology was also cross verified from the DNA sequences data deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan-DDBJ (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp). Evolutionary relatedness between test sequences and retrieved sequences was determined by constructing a Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree in molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA 6) software, using a Kimura 2-parameter model with Gamma distribution (K2 + G), and 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Table 2.

Sequence analysis based on 16S rRNA and identity with accessions available on NCBI database “16S ribosomal RNA sequences (Bacteria and Archaea).

| Isolates | Identified as | Accessions | % similarity | Accessions (NCBI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RWPRB03 | P. putida | MH801129 | 99 | HM486417 |

| RBT7 | P. putida | MH801071 | 99 | KY982927 |

| RB09 | P. libanensis | MH796355 | 98 | DQ095905 |

| AJ-RB13 | P. aeruginosa | MH796356 | 99 | KF420126 |

| DKB53 | B. subtilus | MH796349 | 100 | KX061099 |

| AJ-RB22 | B. megaterium | MH796350 | 100 | MG544100 |

| KSL-24 | B. cereus | MH796347 | 100 | KP236185 |

| KSL-8T | B. cereus | MH796348 | 99 | MF375116 |

Seed germination assay

Rhizobacterial strains were tested for their effect on seed germination before proceeding pot experiments. Chilli pepper seeds (variety; Long green) were surface sterilized by dipping in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 3–5 min and washed three times in dH2O. Disinfected chilli seeds were soaked in 25 ml prepared concentrations of each rhizobacterial suspensions in three concentrations (108 CFU ml−1) by gently shaking for 2 h on the shaker followed by surface drying the bacteria treated seeds on blotter paper. Ten seeds/Petri plates were placed on wet Whatman filter paper No. 41 in each Petri plate, and were incubated at 26 ± 2 °C. Filter papers were kept moist with autoclaved distilled water. Seeds soaked in autoclaved distilled water were kept as control. There were three replications for each treatment and data on seed germination percentage was recorded after 15 days of incubation. The experiment was carried out under a completely randomized design (CRD). Mean values for seed germination were calculated, and data was statistically analyzed. Seed germination percentage was calculated by the following formula:

Greenhouse testing of PGPR for damping-off suppression and growth promotion

Identified rhizobacteria were subjected to check their effect on disease suppression and various plant growth parameters. Pot experiments were performed in the greenhouse located at the Department of Plant Pathology, PMAS Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi. Chilli (variety; Long Green) seeds were surface sterilized with 10% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 5 min followed by six consecutive washings in dH2O. Plastic pots (1.5 l) were filled with autoclaved sandy loam texture soil having physical and chemical properties as; Cation exchange capacity (18 cmol kg−1), pH (7.9), Organic matter (4.3 g kg−1), CaCO3 (76 g kg−1), Electrical conductivity, extract (0.48 dS m−1) Total N (0.2 g kg−1), Total P (267 mg kg−1) and Total K (198 mg kg−1). The soil was flooded with 20 ml sporangial suspension (1 × 103 sporangia ml−1) of P. capsici. Surface sterilized seeds were dipped for 2 h in the bacterial suspension of 108 CFU ml−1 and ten seeds per pot were sown. The control treatment consisted of pots containing soil infested with P. capsici inoculum and distilled water-treated chilli seeds (without bacterial inoculation). All the pots were arranged in complete randomized designed (CRD) in five replications and were placed in the greenhouse. Disease severity was taken on the disease rating scale (DRS) representing 0 = healthy plant; 1 = 1 to 30% wilting; 2 = 31 to 50% wilting; 3 = 51 to 70% wilting; 4 = 71 to 90% wilting; 5 = more than 90% wilting or dead plant31. Data on damping-off disease suppression was recorded 15 days after seed sowing while plant growth parameters were recorded 30 days after sowing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistix 8.1 software and Microsoft Office Excel 2010. A completely randomized design (CRD) was used for all experiments with replicated treatments. Mean values for each treatment were calculated, and all the treatment means were compared via Analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the least significant differences test (LSD) at 5% (P ≤ 0.05) probability level.

Results

Phytophthora capsici and pathogenicity assay

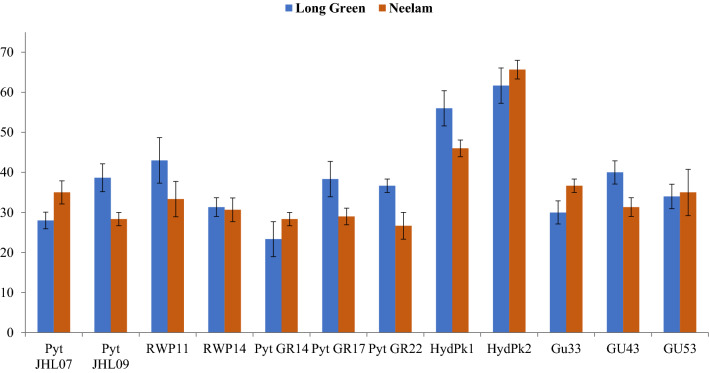

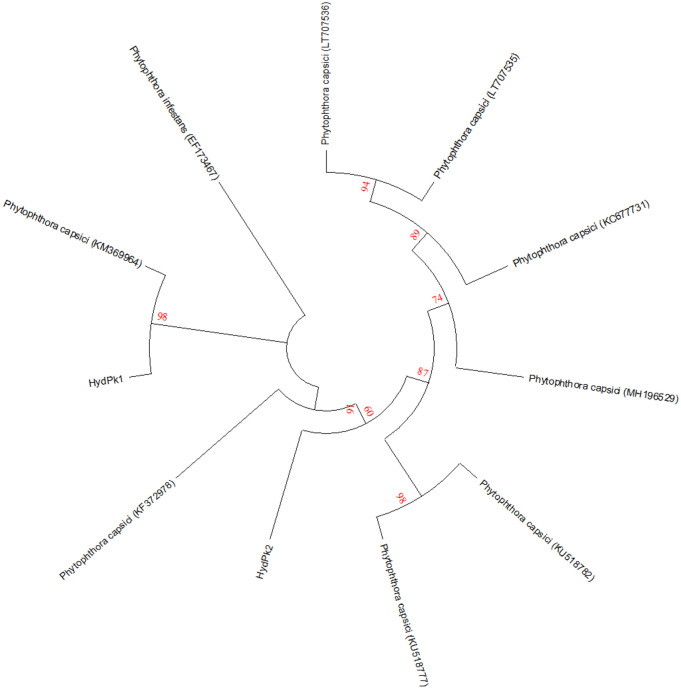

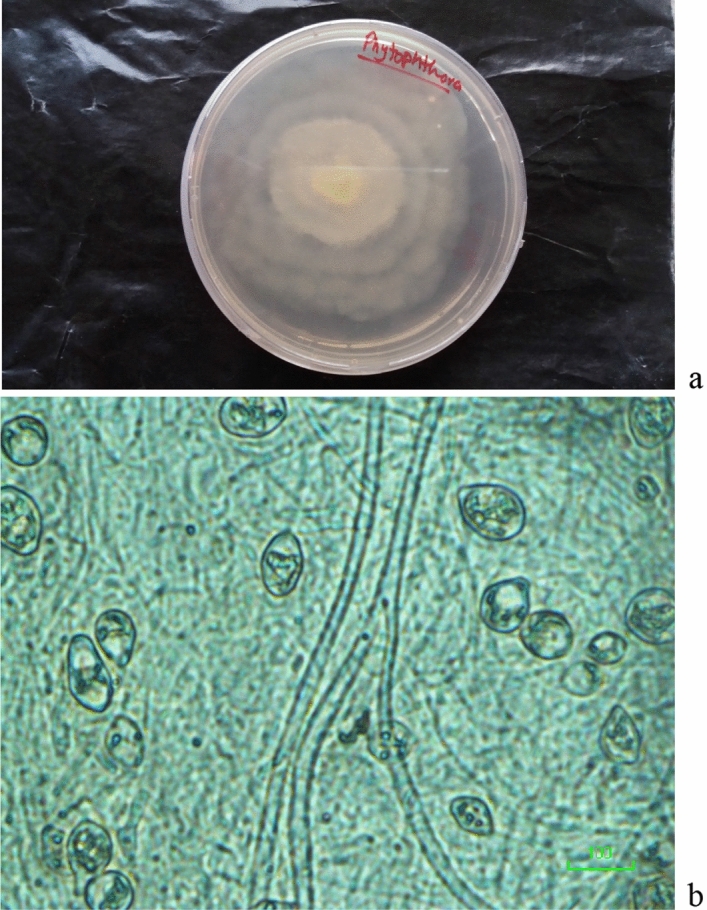

A total of twelve P. capsici isolates were recovered from infected chilli pepper root samples, collected during a survey in Rawalpindi region (33.5651° N, 73.0169° E). Pure culture of P. capsici and the microscopic images are shown (Fig. 1). Two separate experiments under the same environmental conditions were conducted to check the pathogen virulence on the chilli pepper. All the tested isolates varied in their virulence to chilli seedlings and mortality percentage was recorded which ranged from 23.3 to 61.7% on cv. Long Green and 26.7–65.7% on cv. Neelam ( Fig. 2). Out of 12 tested isolates, HydPk1 and HydPk2 showed the highest percentage seedling mortality in both the chilli varieties were ranged 46–56% and 62–66% respectively (Fig. 2) and were highly virulent. The isolate HydPk2 showed maximum seedling mortality on both cultivars; 62% and 66%, it was selected to test in management trials in vitro and in greenhouse.

Figure 1.

(a) Pure culture of P. capsici on CMA-PARPH medium, (b) microscopic image of P. capsici.

Figure 2.

Pathogenicity assay to test seedling mortality percentage in chilli pepper by P. capsici. Long Green and Neelam are the two chilli pepper varieties. Pathogenicity assay was carried out in five replications for each treatment and data on seedling mortality percentage was recorded 15 days after treatment. Mean values were calculated and statistical analysis was performed using Statistix 8.1. All the mean values were subjected to analysis of variance, and means were separated by LSD test at 5% probability. Error bars represent the standard error values of the means.

Characterization of Phytophthora capsici

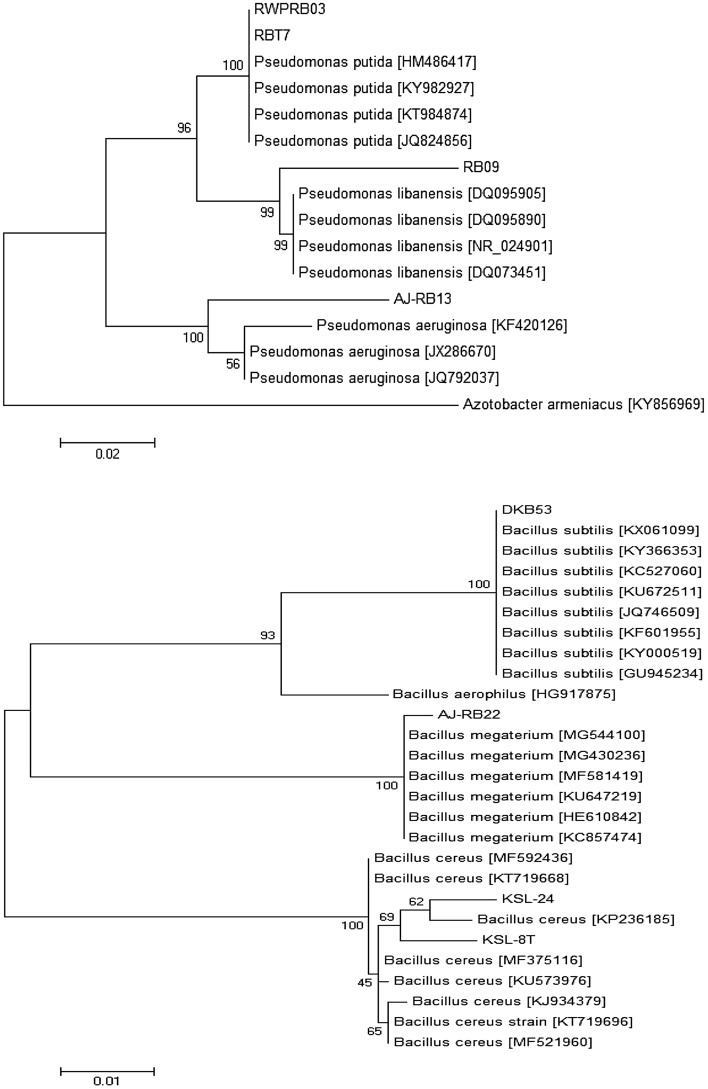

All the isolates produced ovoid, papillate sporangia except RWP14 and GU43 which produced spherical, papillated sporangia. The mean sporangial length among the isolates ranged from 44.7 to 53.1 µm while the sporangial width varied from 24 to 38.4 µm. All the isolates showed pedicle length ranged from 30.6 to 75.5 µm. Maximum pedicle length of 75.5 µm was shown by RWP11 while minimum pedicle length 30.6 µm was observed in HydPk1. Chlamydospores diameter was also recorded in the range of 20.7–29.7 µm (Table 3). Two highly virulent P. capsici (HydPk1 and HydPk2) were subjected to molecular characterization. Internal transcribed spacer regions ITS1 and ITS2 were amplified in both forward and reverse directions and BLAST analysis confirmed 99% identity with those already deposited ITS sequences of P. capsici (KM369964 (Mexico) and KU518782 (India). Evolutionary relationship of all the sequence was determined by constructing a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3). Sequences of HydPk1 and HydPk2 were submitted to GenBank nucleotide database and accessions MF322868 and MF322869 were obtained.

Table 3.

Morphological features of isolates of Phytophthora capsici isolated from chilli pepper fields.

| Isolate code | Sporangial shape | Sporangial length (µm) | Sporangial width (µm) | Pedicle length (µm) | Chlamydospores diameter (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyt JHL07 | Ovoid-papillate | 45.8 ± 3.1ab | 35.7 ± 6.3abc | 71.9 ± 4.4ab | 20.7 ± 1.1b |

| Pyt JHL09 | Ovoid-papillate | 50.0 ± 2.5ab | 32.0 ± 3.7abcd | 70.8 ± 4.2ab | 29.7 ± 1.7a |

| RWP11 | Ovoid-papillate | 52.1 ± 2.3ab | 36.6 ± 4.9ab | 75.5 ± 4.7a | 24.3 ± 2.9ab |

| RWP14 | Spherical-papillate | 53.1 ± 4.4a | 24.0 ± 1.3d | 65.8 ± 2.5ab | 29.0 ± 1.6a |

| Pyt GR14 | Ovoid-papillate | 46.4 ± 1.8ab | 38.4 ± 3.2a | 39.6 ± 3.1cd | 24.8 ± 2.7ab |

| Pyt GR17 | Ovoid-papillate | 45.8 ± 2.8ab | 34.2 ± 3.4abcd | 69.9 ± 5.7ab | 23.6 ± 2.0ab |

| Pyt GR22 | Ovoid-papillate | 49.0 ± 2.5ab | 29.8 ± 2.6abcd | 61.2 ± 3.3b | 25.3 ± 3.5ab |

| HydPk1 | Ovoid-papillate | 45.8 ± 2.2ab | 27.3 ± 2.9bcd | 30.6 ± 2.1d | 24.7 ± 1.0ab |

| HydPk2 | Ovoid-papillate | 44.7 ± 2.2b | 26.1 ± 2.5cd | 37.8 ± 4.5cd | 25.3 ± 1.4ab |

| Gu33 | Ovoid-papillate | 50.6 ± 3.0ab | 29.7 ± 2.0abcd | 74.9 ± 3.8a | 24.2 ± 2.1ab |

| GU43 | Spherical-papillate | 49.1 ± 4.0ab | 35.6 ± 4.1abc | 42.5 ± 3.6c | 26.3 ± 1.6ab |

| GU53 | Ovoid-papillate | 47.3 ± 2.6 ab | 35.1 ± 3.9abc | 41.0 ± 3.3cd | 27.9 ± 2.2ab |

| LSD | 8.1734 | 10.310 | 11.097 | 6.0214 | |

All the presented values are means of twenty replicates. All the means were subjected to analysis of variance and means were separated by LSD test. Letters represent the significant difference among the mean values and ± are standard error values of the means.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationship between the identified strains and representative P. capsici sequences. ITS1 and ITS2 regions of the tested P. capsici isolates were amplified, and all the retrieved and tested sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W program. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method in MEGA-X version 10.1.7 with 1,000 bootstrap replications and the evolutionary distances were calculated by using Jukes–Cantor model.

Antagonism assay against P. capsici in vitro

Antagonism assay was performed to check the potential of rhizobacterial strains in mycelial growth inhibition against P. capsici in vitro. All the tested bacterial strains showed significant antagonism activity against P. capsici in dual culture assay on PDA (Table 4). Out of 15 tested agents, eight bacterial strains were found potential agents against P. capsici and significantly inhibited the mycelial growth 96 h after incubation. Fungal growth inhibition (cm) was ranged 61.7–88.3% over un-inoculated control. Maximum fungal mycelial growth inhibition was done by KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus (88.3%), AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa (85.7%) and RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida (81.1%) while AJ-RB22—Bacillus megatarium was least effective (61.7%) among all the tested bacterial agents over untreated control.

Table 4.

In vitro antifungal activity of rhizobacteria strains on Phytophthora capsici.

| S. no. | Bacterial strains | Fungal mycelia growth 96 h after incubation | Percentage inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida | 0.9 ± 0.08de | 81.1 |

| 2 | RBT7—Pseudomonas putida | 1.3 ± 0.08cd | 74 |

| 3 | RB09—Pseudomonas libansis | 1.6 ± 0.19bc | 68.2 |

| 4 | AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.7 ± 0.08e | 85.7 |

| 5 | DKB53—Bacilus subtilus | 1.6 ± 0.21bc | 68.8 |

| 6 | AJ-RB22—Bacilus megatarium | 1.97 ± 0.12b | 61.7 |

| 7 | KSL-24—Bacilus cereus | 1.3 ± 0.18cd | 75.3 |

| 8 | KSL-8T—Bacilus cereus | 0.6 ± 0.15e | 88.3 |

| 9 | Control | 5.1 ± 0.12a | 0 |

| LSD value | 0.4253 | ||

All the presented values are means of three replicates. Means were subjected to analysis of variance and were separated by LSD test. Letters represent the significant difference among the mean values and ± are standard error values of the means.

Biochemical analysis

Bacterial strains with promising antifungal potential; RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida, RBT7—Pseudomonas putida, RB09—Pseudomonas libansis, AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa, DKB53—Bacillus subtilus, AJ-RB22—Bacillus megatarium, KSL-24—Bacillus cereus and KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus were subjected to biochemical analysis and plant growth promoting (PGP) traits. All the rhizobacteria produced ammonia except strain AJ-RB13, while HCN and catalase test results were positive for all the bacterial strains. For Potassium hydroxide (KOH) test, bacteria belonging to Pseudomonas spp. showed positive response while bacteria from Bacillus spp. showed a negative test results. All the bacterial strains significantly produced IAA, and IAA production was quantified ranging (6.1–56.2 µg ml−1). Maximum IAA was produced by KSL-24—Bacillus cereus (56.2 ± 2.58 µg ml−1) followed by RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida (35.9 µg ml−1) and KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus (29.7 µg ml−1). Siderophore production was exhibited by all the tested rhizobacterial strains ranging (12.5—33.5%). Highest siderophore production percentage was produced by RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida (33.5%) followed by AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa (31.6%) and AJ-RB22—Bacillus megatarium (29.6%) while this activity was observed least in KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus (12.5%) and the results are presented in (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biochemical and plant growth promoting traits of the tested bacterial isolated from chilli pepper.

| Rhizobacterial isolate | AP | HCP | CT | KT | IAA production (µg ml−1) | Siderophore production (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without tryptophan | With tryptophan | ||||||

| RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida | + | + | + | + | 5.6 ± 0.52a | 35.9 ± 3.10b | 33.5 ± 0.9a |

| RBT7—P. putida | + | + | + | + | 2.4 ± 0.09de | 16.9 ± 3.10e | 26.8 ± 1.7c |

| RB09—P. libansis | + | + | + | + | 3.6 ± 0.60bcd | 19.9 ± 1.65de | 21.2 ± 1.4d |

| AJ-RB13—P. aeruginosa | − | + | + | + | 2.9 ± 0.54cd | 6.1 ± 1.03f | 31.6 ± 1.6ab |

| DKB53—Bacilus subtilus | + | + | + | − | 5.4 ± 1.27a | 17.3 ± 1.10e | 16.7 ± 1.7e |

| AJ-RB22—B. megatarium | ± | + | + | − | 1.6 ± 0.52e | 22.9 ± 3.19d | 29.6 ± 0.8b |

| KSL-24—B. cereus | + | + | + | − | 3.7 ± 0.60bc | 56.2 ± 2.58a | 16.4 ± 1.0e |

| KSL-8T—B. cereus | + | + | + | − | 4.2 ± 0.65b | 29.7 ± 3.52c | 12.5 ± 0.3f |

| LSD value | 1.1588 | 4.4717 | 2.1883 | ||||

All the presented values are means of three replicates. Means were subjected to analysis of variance and were separated by LSD test. Letters represent the significant difference among the mean values and ± are standard error values of the means.

AP ammonia production, HCP hydrogen cyanide production, CT catalase test, KT KOH test.

Molecular-based identification of rhizobacterial strains

Bacterial strains with promising antagonistic potential and biochemical traits were identified based on 16S rRNA sequence analysis. Phylogenetic trees constructed from 16S rRNA sequences showed that tested bacterial strains were belonging to Pseudomonas and Bacillus genus (Fig. 4). The Maximum-Likelihood tree indicated that RWPRB03 and RBT7 clustered with P. putida, and showed 99% identity with accessions; HM486417 and KY982927. Bacterial strain RB09 was 98% identical to P. libanensis (DQ095905), while AJ-RB13 clustered with P. aeruginosa and showed 99% sequence homology with accession KF420126. The other four strains viz., DKB53, AJ-RB22, KSL-24 and KSL-8T were closely related to B. subtilus, B. megatarium and B. cereus and showed 99 to 100% identity with accessions: KX061099, MG544100, KP236185 and MF375116 respectively (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationship between the identified Bacillus and Pseudomonas strains and representative bacterial species based on 16S rRNA gene sequences developed with the ClustarW program in MEGA6 and constructed using Maximum-Likelihood method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The values indicate the percentage of clustering matches. Sequence closest matches were based on the NCBI database “16S ribosomal RNA sequences. The scale bar indicates the number of differences in base composition among sequences.

Seed germination assay

Seed germination assay was performed to investigate any positive or negative impact of bacterial strains on chilli seeds at germination stage. The effect of bacterial seed treatment upon seed germination varied with different strains. All bacterial treatments showed a significant effect on the seed germination percentage as compared to control. Seed germination percentage (%) was observed ranging from 73.3 to 93.3% in all the treatments and no stress on seed germination was observed in any treatment. Maximum seed germination was observed in chilli seeds dressed with P. putida (93.3%) followed by P. libanensis and B. subtilus (86.7%). Germination was observed slightly low (73.3%) in P. aeruginosa treated seeds among all the treatments compared to untreated control (Table 6). These results showed that rhizobacterial seed treatment could improve the chilli seed germination without posing any negative impact.

Table 6.

Effect of antagonistic bacterial strains on chilli pepper seed germination in vitro.

| Bacterial isolates (108 cfu ml−1) | Chilli pepper seed germination (%) |

|---|---|

| RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida | 93.3 ± 5.77a |

| RBT7—Pseudomonas putida | 83.3 ± 5.77abc |

| RB09—Pseudomonas libanensis | 86.7 ± 5.77ab |

| AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 73.3 ± 5.77c |

| DKB53—Bacillus subtilis | 86.7 ± 5.77ab |

| AJ-RB22—Bacillus megatarium | 80.0 ± 10.0bc |

| KSL-24—Bacillus cereus | 83.3 ± 11.6abc |

| KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus | 76.7 ± 5.77bc |

| Control | 86.7 ± 5.77ab |

| LSD | 12.352 |

All the presented values are means of three replicates. Means were subjected to analysis of variance and were separated by LSD test. Letters represent the significant difference among the mean values and ± are standard error values of the means.

Greenhouse testing of PGPR for damping-off suppression and PGP effect

Rhizobacteria with high antifungal potential were evaluated for disease suppression and plant growth promotion traits in pot trials under greenhouse conditions. All the tested bacterial strains significantly enhanced the seed germination ranged (75.6–91.1%) as compared to control treatment (57.8%) and reduced the seed mortality caused by P. capsici. However, maximum seed germination was done by DKB53—Bacillus subtilus (91.1%) followed by AJ-RB22—Bacillus megatarium (88.9%) and RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida and KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus (86.7%). Plant growth characters viz., shoot and root length (cm), fresh and dry shoot and root weight (g) were significantly enhanced by the bacterial seed inoculation as compared to untreated control. All the rhizobacterial strains enhanced the shoot and root length in range (9.47–14.67 and 3.30–5.63 in cm) as compared to control where shoot and root length was 3.43 cm and 1.07 cm respectively. All the tested bacterial strains showed a strong ability to produce IAA, thus aided to enhance plant growth characters in chilli pepper. An increase in fresh shoot and root weight was also observed against untreated control treatment. Dry shoot and root weight were also significantly increased over untreated control (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of bacterial isolates on disease suppressiveness and plant growth promotion in chilli pepper in greenhouse conditions.

| Rhizobacterial strains | GP | DRS | MP | Plant growth parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL (cm) | RL (cm) | FSW (g) | FRW (g) | DSW (g) | DRW (g) | ||||

| RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida | 86.7 ± 3.8ab | 1 | 13.3 ± 3.8bc | 11.47 ± 0.58cd | 4.67 ± 0.27bc | 2.3 ± 0.17a | 1.8 ± 0.19ab | 0.51 ± 0.03d | 0.42 ± 0.02c |

| RBT7—P. putida | 80.0 ± 3.8ab | 1 | 20 ± 3.8bc | 10.57 ± 0.52de | 4.27 ± 0.15bc | 2.1 ± 0.15ab | 1.3 ± 0.20bcd | 0.66 ± 0.05c | 0.51 ± 0.04bc |

| RB09—P. libanensis | 84.4 ± 5.9ab | 1 | 15.6 ± 5.9bc | 13.97 ± 0.35ab | 5.03 ± 0.44ab | 1.5 ± 0.23c | 1.6 ± 0.17abcd | 1.08 ± 0.03a | 0.73 ± 0.03a |

| AJ-RB13—P. aeruginosa | 75.6 ± 5.9b | 1 | 24.4 ± 5.9b | 11.37 ± 0.66cd | 3.30 ± 0.26d | 2.3 ± 0.22a | 1.2 ± 0.18d | 0.92 ± 0.11b | 0.44 ± 0.03bc |

| DKB53—Bacillus subtilus | 91.1 ± 2.2a | 1 | 8.9 ± 2.2c | 9.47 ± 0.75e | 4.30 ± 0.21bc | 2.0 ± 0.21abc | 1.7 ± 0.18abc | 0.61 ± 0.03cd | 0.42 ± 0.04c |

| AJ-RB22—B. megatarium | 88.9 ± 4.4a | 1 | 11.1 ± 4.4c | 14.67 ± 0.66a | 5.63 ± 0.20a | 1.8 ± 0.19abc | 1.8 ± 0.09a | 1.13 ± 0.05a | 0.78 ± 0.03a |

| KSL-24—B. cereus | 80.0 ± 3.8ab | 1 | 20 ± 3.8bc | 9.60 ± 0.32e | 4.03 ± 0.38cd | 2.2 ± 0.20ab | 1.3 ± 0.09cd | 0.72 ± 0.05c | 0.47 ± 0.03bc |

| KSL-8T—B. cereus | 86.7 ± 3.8ab | 1 | 13.3 ± 3.8bc | 12.5 ± 0.51bc | 4.43 ± 0.41bc | 1.6 ± 0.18bc | 1.2 ± 0.21cd | 0.59 ± 0.03cd | 0.52 ± 0.03b |

| Control (untreated) | 57.8 ± 2.2c | 3 | 42.2 ± 2.2a | 3.43 ± 0.45f | 1.07 ± 0.30e | 0.8 ± 0.19d | 0.5 ± 0.12e | 0.29 ± 0.03e | 0.2 ± 0.02d |

| LSD value | 12.454 | 12.454 | 1.6417 | 0.9119 | 0.5756 | 0.4863 | 0.1485 | 0.0902 | |

All the presented values are means of five replicates. Means were subjected to analysis of variance, and means were separated by LSD test. Letters represent the significant difference among the mean values and ± are standard error values of the means. Germination percentage and disease data was recorded 15 days after treatment while data on growth promotion parameters was recorded 30 days after sowing. All the results were compared with untreated control where only P. capsici was applied with no bacterial seed inoculation.

GP germination percentage, DRS disease rating scale, MP mortality percentage, SL shoot length, RL root length, FSW fresh shoot weight, FRW fresh root weight, DSW dry shoot weight, DRW dry root weight.

Discussion

Phytophthora capsici is the most destructive plant pathogen, that poses a serious threat by infecting the host plants at any growth stage and causes seedling death, crown rot, foliar blight, and fruit rot. The pathogen causes severe losses in many crops like cucurbits, eggplant, pepper, and tomato15,32. Phytophthora capsici is soil borne in nature and can survive for a long time in soil by forming oospores. Availability of free water support asexual reproduction and pathogen form sporangia and zoospores33 which are dispersed with soil, water, and air currents34. In the present study, P. capsici was isolated from damping-off chilli root samples showing the characteristic symptoms of rotten roots, decay, wilt and necrosis35 and a total of 12 isolates were recovered and purified. Pathogenicity assay was performed to screen the most virulent isolates as different isolates have varied level of virulence. A research study suggested that P. capsici isolates from pepper and pumpkin differ in virulence levels32. Morphologically identification confirmed the production of papillate sporangia on long pedicels, and Chlamydospores and these findings are supported by a study of36. According to37, Chamydospores production is not much common in Capsicum isolates but the formation of Chamydospores in P. capsici isolates depends on the cultural methods and the origin of the host38. Two most aggressive isolates (HydPk1 and HydPak2) screened in pathogenicity assays were subjected to molecular identification by amplifying ITS1 and ITS2 regions19,20, and were identified as P. capsici. In another study, pathogen was identified as Phytophthora colocasiae on the basis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence homology39. Other researchers have also identified P. capsici by amplifying ITS regions of the isolates collected from chilli pepper blight samples40.

Rhizobacteria colonizing the rhizosphere interact with crops in various ways; by controlling the plant diseases by antagonism and by promoting plant growth parameters41. The interaction of beneficial rhizobacteria and plant-phytopathogen could offer new strategies to enhance plant productivity in an environment friendly way42. Rhizobacteria with plant growth promoting potential are used as an alternative to chemical pesticides in the agriculture industry43. Various researches have proved that upon attack by soil-borne fungal pathogens, plants can exploit microbial consortia from the soil for protection against infections, restructuring bacterial communities associated with rhizosphere44. In our study, fifteen rhizobacterial strains were recovered from chilli rhizosphere, majorly belonged to the genera Bacillus and Pseudomonas. Our findings are comparable to various reports on biocontrol potential of bacteria belonging to genera Achromobacter, Arthrobacter, Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Clostridium, Enterobacter, Flavobacterium, Micrococcus and Pseudomonas being the most common bacterial groups prevailing in soil45,46.

Biological control of P. capsici can be due to antagonistic ability of the bacterial strains47,48. Initially, fifteen bacterial strains were screened for antagonism against P. capsici. All the tested bacterial strains showed varied levels of antagonistic potential. Results revealed that five bacterial isolates viz., RWPRB03—Pseudomonas putida, RBT7—Pseudomonas putida, AJ-RB13—Pseudomonas aeruginosa, KSL-24—Bacillus cereus, and KSL-8T—Bacillus cereus showed > 70% mycelial growth inhibition of P. capsici. In a research study, out of 811 tested rhizospheric bacteria, five bacterial strains showed highest antagonistic potential against three most prevalent strains of bacterial leaf blight (BLB) pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae49. Biocontrol potential of tested bacterial isolates could be due to antibiosis and various antibiotics have been previously identified and reported by many researchers50,51. It has been reported that production of various antimicrobial compounds are responsible for fungal growth inhibition as these compounds result into cytolysis, leakage of potassium ions, disruption of the structural integrity of membranes, inhibition of mycelial growth, spore germination inhibition and protein biosynthesis52. Antifungal potential of Bacillus spp. attributed to the production of various levels of different lipopeptides against varying fungal phytopathogens53 while Dimethyl disulfide and other sulfur-containing compounds production by Pseudomonas spp. were studied to stop the mycelial growth of P. infestans54 and various other volatile compounds emitted by Pseudomonas spp., such as 1-Undecene, also reduce sporangia formation and release of zoospores in P. infestans55.

Most of the tested bacteria exhibited multiple PGP traits which aid to growth promotion and disease reduction capability of PGPR. Such multiple modes of action have been researched to be the prime reasons for the plant growth promotion and disease suppressing potential of PGPR56. It is important to explore the potential of native rhizobacterial strains for their PGP traits to get the desired benefits on disease control and plant growth promotions. In this study, eight bacterial strains with strong antagonistic potential were screened for biochemical and plant growth promotion characters. All tested bacterial strains showed a positive response to ammonia production, Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production, catalase reaction, KOH test (Bacillus spp.), IAA and siderophore production. Ammonia (NH3) production is important feature of PGPR, which indirectly enhances the plant growth57. It accumulates and supply nitrogen to their host plants and promotes plant growth58. Various studies have reported the ammonia production by rhizobacteria3,59,60. In our studies, except one bacterial strain, all were positive for ammonia production. All the tested bacterial strains were positive for HCN production test. It was originally believed that HCN production play its role in plant growth promotion by suppressing the plant pathogens61,62. However, this concept has recently been changed. It has been believed that HCN production indirectly increases phosphorus availability by chelation and sequestration of metals, and indirectly increases the nutrient availability to the rhizobacteria and host plants63. The production of HCN by PGPR are independent of their genus, thus they are used as biofertilizers or biocontrol to enhance crop production64 and these are being used as biofertilizer in growth promotion and yield enhancement. All the tested bacterial strains were catalase positive. Previous studies have reported the production of antioxidant enzymes like catalase by rhizobacteria65 which suppressed early blight disease in tomato66 and induced resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl virus67. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is secondary metabolites, and its production in bacterial agents is generally described based on their ability to use tryptophan supplemented in the growth medium, which is the major precursor of IAA biosynthesis via indole pyruvic acid (IPA) pathway68. It supports root development, elongation and proliferation and help plants to take up water and nutrients from soil69. All the tested bacterial strains produced IAA in various concentrations and this varying ability could be due to the difference in bacterial physiological characters, however70 reported that Indolepyruvic decarboxylase (IPDC) is the enzyme which determines IAA biosynthesis. All the tested strains belonging to Bacillus and Pseudomonas spp. produced IAA even in the growth medium without tryptophan as supplementary material. Siderophore was also produced by all the tested bacterial strains ranged from 12.5 to 33.5%. These findings are further supported by previous reports in which siderophore production was reported as an important mechanism involved in the suppression of bacterial leaf blight (BLB) disease71. Siderophore is one of the major biocontrol mechanisms exhibited by various plant growth promoting rhizobacterial groups under iron-limiting condition. PGPR produces a wide range of siderophore which has a high affinity for iron thus, lowering the availability of iron to pathogenic agents including plant pathogenic fungi72. Siderophore production by PGPR controls soil-borne pathogenic fungi by limiting iron availability to them73. The antagonistic potential of the selected bacterial strains might be due to the siderophores and HCN production or synergistic interaction of these two or with other metabolites49.

The 16S rRNA sequences have been widely used in the classification and identification of Bacteria and Archaea74. In our studies, 16S rRNA sequence based maximum-likelihood tree indicated that tested bacterial strains RWPRB03 and RBT7 showed 99% sequence homology with P. putida (accessions; HM486417 and KY982927), while RB09 was 98% identical to P. libanensis (DQ095905). AJ-RB13 clustered with P. aeruginosa and showed 99% homology with accession KF420126. The other four bacterial strains viz., DKB53, AJ-RB22, KSL-24 and KSL-8T showed 99 to 100% sequence homology with accessions: KX061099, MG544100, KP236185 and MF375116 respectively. Similarly, Ref75 reported that 16S rRNA sequence based characterization indicated that most of the bacterial strains isolated from cucumber rhizosphere belonged to Pseudomonas stutzeri, Bacillus subtilis, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and B. amyloliquefaciens.

Studies have proved that seed treatment is an effective strategy to enhance seedling emergence, seed vigor, and to prevent seed and soil borne pathogens76. Chemical seed treatment is a major practice being followed to prevent damping off disease77,78. Many kinds of chemicals are used to remove the pathogen inoculum from seed coats76 but these chemicals could negatively affect seed germination, cause phytotoxicity79, pose a negative impact on human health and environment80. Results from our studies indicated that seed treatment with bacterial strains significantly enhanced the seed germination over untreated control, and no phytotoxicity was observed in any treatment and our results are supported by the finding of75. In a study, high amylase activity during germination was observed in rice and legume inoculated with PGPR79 which support the root and shoot germination in young seedlings.

Results from our study indicate that seed treatment with PGPR significantly reduced the seedling mortality and disease severity of P. capsici in chilli pepper and studies have proved the role of rhizobacteria as biological control agents81,82. Various studies have reported the antifungal potential of rhizobacteria belonging to Pseudomonas and Bacillus spp. against P. infestans and P. capsici83,84. Results from our study showed that eight bacterial strains significantly suppress the damping off disease, and enhanced the plant growth in pot experiments. The results from greenhouse trials suggested that the tested PGPR slightly differ in their effects on disease suppression and PGP traits in chilli, and all the tested bacterial strains performed better under greenhouse conditions compared to untreated control. Earlier researches have revealed that the PGP effects and disease reduction potential of rhizobacteria are attributed to multiple traits56. Our results on chilli disease suppression and PGP are supported by other studies on growth promotion by PGPR in common bean85 and tomato86. In another study, strains of PGPR from cucumber plants rhizosphere were tested for their plant growth promoting traits and antifungal potential against Phytophthora crown rot of cucumber seedlings under in vitro and greenhouse conditions. Results revealed that tested rhizobacterial strains protected the plants by various modes of action including antibiosis against target pathogen, competitive colonization, and plant growth promotion75. These findings support the utilization of these rhizobacterial strains for bioformulations development their commercial use as biocontrol agents in the open fields.

It has been reported that the field application of bacterial based products has been hampered because of their low performance due to various climatic and soil factors87,88. This is important to test the efficacy of native rhizobacteria under the same environmental condition where they would be used in plant growth promotion. It was concluded in various studies that environmental factors significantly influence the rhizobacterial colonization, biological activates, and disease suppressing potential89–91. In the majority of the cases, bacterial based formulations imported from the other counters bearing different climatic conditions failed to perform up to their maximum potential under warm environmental conditions prevailing in Pakistan. In this study, bacterial strains were isolated from the local fields located in Pakistan and were tested for their potential to suppress the soil-borne oomycetes and plant growth promotion in chilli pepper. Development of bioformulations on available carrier materials is undergoing. To find out optimized formulations dose level and appropriate application method, it requires a series of experiments with different soil types under greenhouse and open field conditions, and these studies are under progress.

Conclusions

Out of fifteen, eight bacterial strains efficiently suppressed the mycelial growth of pathogenic Phytophthora capsici in direct interactions-assays in vitro. Bacterial strains with strong anti-fungal potential were found positive for HCN, catalase test, Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and siderophore production. The 16S rRNA sequence analysis of bacterial strains showed 98 to 100% identity with close relatives belonging to Bacillus and Pseudomonas genera. Greenhouse studies revealed that bacterial strains suppressed the P. capsici and significantly enhanced the plant growth characters in chilli pepper. These results confirmed the significant role of native rhizobacteria for the control of soil-borne oomycetes and the potential use of Bacillus and Pseudomonas spp. in bio-fertilizers and bio-fungicides development.

Acknowledgements

Financial support received from Punjab Education Commission (PHEC) and Punjab Agriculture Research Board (PARB), Pakistan for carrying out this research work is gratefully acknowledged. We also acknowledge Professor Youfu Frank Zhao, Department of Crop Sciences, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for providing bench space in his laboratory and helping in various research activities.

Author contributions

S.H., A.S.G., N.F. Conceived the presented idea, planned and carried out research experiments and wrote the paper. M.M.A., R.A., Z.F.R. Helped authors in DNA sequence analysis. W.A. Contributed to sample preparation and helped in performing different tests. A.H. Helped authors in the interpretation of results. M.I. Helped the first author during research as major supervisor.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lamour KH, Stam R, Jupe J, Huitema E. The oomycete broad-host-range pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012;13:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanogo S, Ji P. Integrated management of Phytophthora capsicion solanaceous and cucurbitaceous crops: current status, gaps in knowledge and research needs. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2012;34:479–492. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2012.732117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu SJ, Kim BS. Biocontrol of Fusarium crown and root rot and promotion of growth of tomato by Paenibacillus strains isolated from soil. Mycobiology. 2014;42:158–166. doi: 10.5941/myco.2014.42.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osburn RM. Dynamics of sugar beet seed colonization by Pythium ultimum and Pseudomonas species: effects on seed rot and damping-off. Phytopathology. 1989;79:709. doi: 10.1094/phyto-79-709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;63:541–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar P, Dubey RC, Maheshwari DK. Bacillus strains isolated from rhizosphere showed plant growth promoting and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens. Microbiol. Res. 2012;167:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaharoona B, Arshad M, Zahir Z, Khalid A. Performance of Pseudomonas spp. containing ACC-deaminase for improving growth and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) in the presence of nitrogenous fertilizer. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006;38:2971–2975. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavino M, Harish S, Kumar N, Saravanakumar D, Samiyappan R. Effect of chitinolytic PGPR on growth, yield and physiological attributes of banana (Musa spp.) under field conditions. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010;45:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurabachew H, Wydra K. Characterization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their potential as bioprotectant against tomato bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Biol. Control. 2013;67:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul D, Sarma YR. Plant growth promoting rhizhobacteria (PGPR)-mediated root proliferation in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) as evidenced through GS Root software. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2006;39:311–314. doi: 10.1080/03235400500301190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt CS, Agostini F, Leifert C, Killham K, Mullins CE. Influence of soil temperature and matric potential on sugar beet seedling colonization and suppression of Pythium damping-off by the antagonistic bacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology. 2004;94:351–363. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zohara F, Akanda MAM, Paul NC, Rahman M, Islam MT. Inhibitory effects of Pseudomonas spp. on plant pathogen Phytophthora capsici in vitro and in planta. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016;5:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joo GJ. Production of an anti-fungal substance for biological control of Phytophthora capsici causing phytophthora blight in red-peppers by Streptomyces halstedii. Biotech. Lett. 2005;27:201–205. doi: 10.1007/s10529-004-7879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Islam S, Babadoost M, Lambert KN, Ndeme A, Fouly H. Characterization of Phytophthora capsici isolates from processing pumpkin in Illinois. Plant Dis. 2005;89:191–197. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ristaino J. Intraspecific variation among isolates of Phytophthora capsici from pepper and cucurbit fields in North Carolina. Phytopathology. 1990;80:1253–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granke L, Quesada-Ocampo L, Hausbeck M. Variation in phenotypic characteristics of Phytophthora capsici isolates from a worldwide collection. Plant Dis. 2011;95:1080–1088. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-03-11-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White, T. J. (ed M A Innis) 135 (Academic Press, 1990).

- 18.Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. New York: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooke DE, Duncan JM. Phylogenetic analysis of Phytophthora species based on ITS1 and ITS2 sequences of the ribosomal RNA gene repeat. Mycol. Res. 1997;101:667–677. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinesh R, et al. Isolation, characterization, and evaluation of multi-trait plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for their growth promoting and disease suppressing effects on ginger. Microbiol. Res. 2015;173:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg G, Fritze A, Roskot N, Smalla K. Evaluation of potential biocontrol rhizobacteria from different host plants of Verticillium dahliae Kleb. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;91:963–971. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dye D. The inadequacy of the usual determinative tests for the identification of Xanthomonas spp. N. Z. J. Sci. 1962;5:393–416. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller R, Higgins VJ. Association of cyanide with infection of birdsfoot trefoil by Stemphylium loti. Phytopathology. 1970;60:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayward A. A method for characterizing Pseudomonas solanacearum. Nature. 1960;186:405–406. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirsop BE, Doyle AC. Maintenance of Microorganisms and Cultured Cells. New York: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasri K, Kaewharn J, Kanso S, Sangchanjiradet S. Optimization of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production by rhizobacteria isolated from epiphytic orchids. Asia Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2014;19:268–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reysenbach A-L, Giver LJ, Wickham GS, Pace NR. Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58:3417–3418. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3417-3418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quesada-Ocampo LM, Hausbeck MK. Resistance in tomato and wild relatives to crown and root rot caused by Phytophthora capsici. Phytopathology. 2010;100:619–627. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-100-6-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee BK, Kim BS, Chang SW, Hwang BK. Aggressiveness to pumpkin cultivars of isolates of Phytophthora capsici from pumpkin and pepper. Plant Dis. 2001;85:497–500. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowers J, Papavizas G, Johnston S. Effect of soil temperature and soil-water matric potential on the survival of Phytophthora capsici in natural soil. Plant Dis. 1990;74:771–777. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ristaino JB, Larkin RP, Campbell CL. Spatial dynamics of disease symptom expression during Phytophthora epidemics in bell pepper. Phytopathology. 1994;84:1015–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horst RK. Westcott's Plant Disease Handbook. Berlin: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawaz K, Shahid AA, Subhani MN, Iftikhar S, Anwar W. First report of leaf spot caused by Phytophthora capsici on chili pepper (Capsicum frutescens L.) in Pakistan. J. Plant Pathol. 2018;100:127–127. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartual R, Marsal J, Carbonell E, Tello J, Campos T. Genética de la resistencia a Phytophthora capsici Leon en pimiento. Boletín de sanidad vegetal. Plagas. 1991;17:3–124. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erwin DC, Ribeiro OK. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide. St. Paul: APS Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misra RS, Mishra AK, Sharma K, Jeeva ML, Hegde V. Characterisation of Phytophthora colocasiae isolates associated with leaf blight of taro in India. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2011;44:581–591. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zapata-Vázquez, A., Sánchez-Sánchez, M., del-Río-Robledo, A., Silos-Espino, H., Perales-Segovia, C., Flores-Benítez, S., González-Chavira, M.M. and Valera-Montero, L.L. Phytophthora capsici epidemic dispersion on commercial pepper fields in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Sci. World J.2012, 01-05. 10.1100/2012/341764 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Schenk PM, Carvalhais LC, Kazan K. Unraveling plant microbe interactions: can multi species transcriptomics help? Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Timmusk S, Behers L, Muthoni J, Muraya A, Aronsson A-C. Perspectives and challenges of microbial application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:49. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kloepper, J. W., Tuzun, S., Liu, L. & Wei, G. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as inducers of systemic disease resistance. Pest Management: Biologically Based Technologies. American Chemical Society Books, Washington, DC, 156–165 (1993).

- 44.Mendes R, et al. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease suppressive bacteria. Science. 2011;332:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felici C, et al. Single and co-inoculation of Bacillus subtilis and Azospirillum brasilense on Lycopersicon esculentum: effects on plant growth and rhizosphere microbial community. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2008;40:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swain MR, Ray RC. Biocontrol and other beneficial activities of Bacillus subtilis isolated from cowdung microflora. Microbiol. Res. 2009;164:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung S, et al. Isolation and partial characterization of Bacillus subtilis ME488 for suppression of soilborne pathogens of cucumber and pepper. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;80:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1520-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim J-H, Kim S-D. Biocontrol of Phytophthora blight of red pepper caused by Phytophthora capsici using Bacillus subtilis AH18 and B. licheniformis K11 formulations. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2010;53:766–773. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasmin S, et al. Plant growth promotion and suppression of bacterial leaf blight in rice by inoculated bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0160688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raaijmakers JM, Vlami M, De Souza JT. Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:537. doi: 10.1023/a:1020501420831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen TH, Sørensen J. Production of cyclic lipopeptides by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains in bulk soil and in the sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:861–868. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.861-868.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan J, et al. Production of Bacillomycin and Macrolactin type antibiotics by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6 for suppressing soilborne plant pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:2976–2981. doi: 10.1021/jf204868z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cawoy H, et al. Lipopeptides as main ingredients for inhibition of fungal phytopathogens by Bacillus subtilis/amyloliquefaciens. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014;8:281–295. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Vrieze M, et al. Volatile organic compounds from native potato associated Pseudomonas as potential anti-oomycete agents. Front. Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunziker L, et al. Pseudomonas strains naturally associated with potato plants produce volatiles with high potential for inhibition of Phytophthora infestans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;81:821–830. doi: 10.1128/aem.02999-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bashan Y, de-Bashan LE. Advances in Agronomy. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 77–136. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yadav J, Verma JP, Tiwari KN. Effect of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on seed germination and plant growth chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) under in vitro conditions. Biol. For. 2010;2:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar M, et al. Synergistic effect of Pseudomonas putida and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ameliorates drought stress in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Plant Signal. Behav. 2016;11:e1071004. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1071004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jayasinghearachchi H, Seneviratne G. A bradyrhizobial-Penicillium spp. biofilm with nitrogenase activity improves N 2 fixing symbiosis of soybean. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2004;40:432–434. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Triveni S, Prasanna R, Saxena AK. Optimization of conditions for in vitro development of Trichoderma viride-based biofilms as potential inoculants. Folia Microbiol. 2012;57:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s12223-012-0154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voisard C, Keel C, Haas D, Dèfago G. Cyanide production by Pseudomonas fluorescens helps suppress black root rot of tobacco under gnotobiotic conditions. EMBO J. 1989;8:351–358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Defago, G., Berling, C.H., Burger, U., Haas, D., Kahr, G., Keel, C., Voisard, C., Wirthner, P.H. and Wüthrich, B. Suppression of black root rot of tobacco and other root diseases by strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens: Potential applications and mechanisms. Biol. Control Soil Borne Plant Pathog. 34, 93–108 (1990).

- 63.Rijavec T, Lapanje A. Hydrogen cyanide in the rhizosphere: not suppressing plant pathogens, but rather regulating availability of phosphate. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1785. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agbodjato, N.A., Noumavo, P.A., Baba-Moussa, F., Salami, H.A., Sina, H., Sèzan, A., Bankolé, H., Adjanohoun, A. and Baba-Moussa, L. Characterization of potential plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolated from Maize (Zea mays L.) in central and Northern Benin (West Africa). Appl. Environ. Soil Sci.2015, 01–09. 10.1155/2015/901656 (2015).

- 65.Kamboh AA, Rajput N, Rajput IR, Khaskheli M, Khaskheli GB. Biochemical properties of bacterial contaminants isolated from livestock vaccines. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009;8:578–581. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2009.578.581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Senthilraja G, Anand T, Kennedy J, Raguchander T, Samiyappan R. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and entomopathogenic fungus bioformulation enhance the expression of defense enzymes and pathogenesis-related proteins in groundnut plants against leafminer insect and collar rot pathogen. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013;82:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li H, et al. Control of tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease by Enterobacter asburiaeBQ9 as a result of priming plant resistance in tomatoes. Turk. J. Biol. 2016;40:150–159. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patten CL, Glick BR. Bacterial biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid. Can. J. Microbiol. 1996;42:207–220. doi: 10.1139/m96-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao T, Yasmin S, Hafeez FY. Potential role of rhizobacteria isolated from Northwestern China for enhancing wheat and oat yield. J. Agric. Sci. 2008;146:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patten CL, Glick BR. Role of Pseudomonas putida indoleacetic acid in development of the host plant root system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:3795–3801. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.8.3795-3801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Naureen Z, Price AH, Hafeez FY, Roberts MR. Identification of rice blast disease-suppressing bacterial strains from the rhizosphere of rice grown in Pakistan. Crop Prot. 2009;28:1052–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whipps JM. Microbial interactions and biocontrol in the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2001;52:487–511. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scavino AF, Pedraza RO. Bacteria in Agrobiology: Crop Productivity. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goodfellow M, Sutcliffe I, Chun J. New Approaches to Prokaryotic Systematics. Ne York: Academic Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Islam S, Akanda AM, Prova A, Islam MT, Hossain MM. Isolation and identification of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from cucumber rhizosphere and their effect on plant growth promotion and disease suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2016;6:1360. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mancini V, Romanazzi G. Seed treatments to control seedborne fungal pathogens of vegetable crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014;70:860–868. doi: 10.1002/ps.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rothrock C, et al. Importance of fungicide seed treatment and environment on seedling diseases of cotton. Plant Dis. 2012;96:1805–1817. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-12-0031-SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kandel YR, et al. Fungicide and cultivar effects on sudden death syndrome and yield of soybean. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1339–1350. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-15-1263-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.du Toit, L. J. Management of diseases in seed crops. In Encyclopedia of Plant and Crop Science (ed Dekker, G. R.M.) 675–677 (New York, 2004).

- 80.Lamichhane JR, Dachbrodt-Saaydeh S, Kudsk P, Messéan A. Toward a reduced reliance on conventional pesticides in European agriculture. Plant Dis. 2016;100:10–24. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-05-15-0574-FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Idris HA, Labuschagne N, Korsten L. Screening rhizobacteria for biological control of Fusarium root and crown rot of sorghum in Ethiopia. Biol. Control. 2007;40:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sarbadhikary SB, Mandal NC. Field application of two plant growth promoting rhizobacteria with potent antifungal properties. Rhizosphere. 2017;3:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2017.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munjal V, et al. Genotyping and identification of broad spectrum antimicrobial volatiles in black pepper root endophytic biocontrol agent, Bacillus megaterium BP17. Biol. Control. 2016;92:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lazazzara V, et al. Growth media affect the volatilome and antimicrobial activity against Phytophthora infestans in four Lysobacter type strains. Microbiol. Res. 2017;201:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Egamberdieva D. Survival of Pseudomonas extremorientalis TSAU20 and P. chlororaphis TSAU13 in the rhizosphere of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) under saline conditions. Plant Soil Environ. 2011;57:122–127. doi: 10.1721/316/2010-pse. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Almaghrabi OA, Massoud SI, Abdelmoneim TS. Influence of inoculation with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on tomato plant growth and nematode reproduction under greenhouse conditions. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2013;20:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ross IL, Alami Y, Harvey PR, Achouak W, Ryder MH. Genetic diversity and biological control activity of novel species of closely related Pseudomonads isolated from wheat field soils in South Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1609–1616. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1609-1616.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ownley BH, Duffy BK, Weller DM. Identification and manipulation of soil properties to improve the biological control performance of Phenazine producing Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:3333–3343. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.6.3333-3343.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beauchamp C, Kloepper J, Chalifour F, Antoun H. Effects of temperature on growth promotion and root colonization of potato by bioluminescent rhizobacteria mutants. Plant Growth Promot. Rhizobacteria Prog. Prospect. Bull. OILB. 1991;14:332–335. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Olsen C. Selective heat treatment of soil and its effect on the inhibition of Rhizoctonia solani by Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology. 1968;58:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Landa BB, Navas-Cortés JA, Hervás A, Jiménez-Díaz RM. Influence of temperature and inoculum density of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris on suppression of Fusarium wilt of chickpea by rhizosphere bacteria. Phytopathology. 2001;91:807–816. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]